Abstract

Human type I interferons (IFNs) comprise one IFN-β, -ω, -κ, and -ɛ and 12 different IFN-α subtypes, which play an important role in early host antiviral response. Despite their high structural homology and signaling through the same receptor, IFN-α subtypes exhibit different antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory activities. Differences in the production of IFN-α subtypes therefore determine the quality of an antiviral response. In this study, we investigated the pattern of IFN-α subtypes induced in infection with different mumps virus (MuV) strains and examined the MuV sensitivity to the action of IFN-α subtypes. We found that all IFN-α subtypes are being expressed in response to MuV infection with a highly similar IFN-α subtype pattern between the virus strains. We assessed an antiviral activity of several IFN-α subtypes: IFN-α1, IFN-α2, IFN-α4, IFN-α6, IFN-α8, IFN-α14, IFN-α17, and IFN-α21. Although they were all effective in suppressing MuV replication, the intensity and pattern of their action varied between MuV strains. Our results indicate that the overall IFN antiviral activity as well as the activity of specific IFN-α subtypes against MuV depend on a virus strain.

Introduction

The interferons (IFNs) are the family of cytokines that are capable of controlling most virus infections before the development of an adaptive immunity and, therefore, prevent an overwhelming infection. Among the three groups of IFNs (type I, II, and III), the type I IFN can be produced by any cell type rapidly after recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by cellular receptors. The type I IFN comprises a large group of molecules that include even 12 IFN-α subtypes and one IFN-β, -ω, -κ, and -ɛ in humans (28). They are produced in a two-step amplification loop regulated by IFN regulatory factors, IRF-3 and IRF-7 (14,15). Viral sensing first induces activation and nuclear localization of IRF-3, which stimulates transcription, synthesis, and secretion of IFN-β from infected cells. In the following step, IFN-β binds to the ubiquitously expressed heterodimeric receptor (IFNAR) to activate the JAK/STAT signal transduction pathway that triggers the transcription of a diverse set of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) and establish an antiviral response in target cells (29). One of the transcribed ISGs is IRF-7, which promotes production of additional IFN-β and different IFN-α subtypes through a positive feedback loop. Whereas IRF-3 is constitutively expressed in most tissues, only cells of lymphoid origin (e.g., plasmacytoid cells) were found to have high basal levels of IRF-7 (3).

IFN-α subtypes arise from 13 intronless IFNA genes (IFNA1 and IFNA13 encode the same protein) that cluster together in a 400 kb region on the human chromosome 9 (11) and are highly homologous. Despite binding to the same receptor, these IFN-α subtypes exhibit different antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory activities (12). The qualitative and quantitative differences in the production of IFN-α subtypes therefore influence the shape, intensity, and duration of an antiviral response. Only few studies reported on the distinct antiviral activities of specific IFN-α subtypes employing in vitro and in vivo models of virus infection [reviewed in Gibbert et al. (12)]. The redundancy of an IFN-α system is still unintelligible, demanding more research on individual IFN-α subtypes to define their specific antiviral activities.

Mumps virus (MuV) is a negative-stranded RNA virus and a member of the Paramyxoviridae family. It causes mumps disease only in humans, which is primarily characterized by the parotid gland swelling but often accompanied by serious side effects like viral encephalitis, meningitis, orchitis, or deafness (16). Although mumps incidence has largely declined through vaccination, local mumps outbreaks occur sporadically due to a low coverage of vaccination or vaccine ineffectiveness (8).

As other paramyxoviruses, MuV has employed the activity of nonstructural V protein to counter the effects of type I IFNs through suppression of IFN production (1,24,29) or interference with IFN signal transduction (20,21). However, the sensitivity of MuV to specific IFN-α subtypes as well as the potential difference in sensitivity between the MuV strains have never been addressed.

The aim of our study was to investigate the pattern of expression of IFN-α subtypes in response to MuV infection and MuV sensitivity to the action of IFN-α subtypes. To be able to understand how the level of attenuation affects the virus ability to induce and resist the IFN response, we tested one vaccine (Jeryl Lynn 5 [JL5]) and one wild-type (9218/Zg98) MuV strain. The knowledge on this aspect of innate immunity would improve our understanding of the early stage of MuV pathogenesis and be valuable when choosing new MuV vaccine candidates.

Materials and Methods

Cells and viruses

African green monkey kidney cells (Vero) and human fetal lung fibroblasts (MRC-5) were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Culture (ECACC) and maintained in the Minimum essential medium with Hank's salts (MEM-H) (AppliChem) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Moregate) and 50 μL/mL neomycin (Gibco-BRL). Human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (A549) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) (AppliChem) supplemented with 10% FCS and 50 μL/mL neomycin. CHO-ISRE-SEAP cells were a nice gift from V. Smilović (National Institute of Chemistry, Ljubljana) (34). The MuV wild-type strain 9218/Zg98 was isolated from a single case patient in Croatia in 1998 (30). The JL5 MuV vaccine strain was kindly provided by B. Rima (the Queen's University of Belfast, UK). Both MuV strains were grown at multiplicity of infection (MOI) 0.05 and incubated at 35°C for two passages in Vero cells until the observation of a strong cytopathic effect.

Detection of defective interfering particles by RT-PCR

RNA was extracted as reported by Branovic et al. (5). An RT-PCR method described by Calain et al. (6) was herein adapted for the amplification of copy-back defective-interfering particles' (DIPs) genomes of MuV. Total RNA together with 20 pmol of L25 primer (5′-ACCAAG GGGAGAAAGTAAAATC-3′) was denatured at 70°C for 10 min and the rest of the RT mix was added on ice. RT was performed with MuLV reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems) at 42°C for 89 min and 95°C for 5 min. A total cDNA was used in PCR with specific primers L25 and L23 (5′-CTGATGATTGGCCCTTTAGGA-3′), 1× PCR, 10 μM dNTP, 0.25 mM MgCl2, 0.4 μM of each primer, and 5 U of Taq polymerase (GE Healthcare Life Science). PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, then 40 cycles 94°C/30 sec, 55°C/20 sec, and 72°C/2 min, followed by final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized after electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Infection of A549 and MRC-5 cells

The A549 or MRC-5 cells were infected with MuV in a cell monolayer at MOI 1 (for IFN-α induction experiment, analysis of IFN-α antiviral activity and western blot analysis) or at MOI 3 (for quantification of type I IFN). One hour following adsorption at 35°C, virus was removed, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco-BRL), and supplied with a fresh medium containing 2% FCS.

Quantitative RT-PCR

The total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and treated with the Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion) for removal of gDNA contamination. Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg of RNA with MuLV reverse transcriptase and Oligo(dT) primers (both from Applied Biosystems). Primer pairs used to amplify the human IFNL1 gene were 5′-CGCCTTGGAAGAGTCACTCA-3′ and 5′-GAAGCCTCAGGTCCCAATTC-3′ (2), and the final PCR mix contained 1x Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies), 0.133 μM of each primer, and 3 μL of cDNA.

The human IFNB1 gene was amplified using TaqMan gene expression assay for IFNB1 (Applied Biosystems, assay identification code Hs01077958_s1). The amount of transcripts was first normalized against the GAPDH gene transcript and amplified using Human GAPD (GAPDH) Endogenous Control (VIC®/MGB probe, primer limited) (Applied Biosystems). As the mock-infected samples were negative for IFN-β and IFN- λ1, obtained values were normalized against values for samples with the highest Ct values to obtain relative gene expression ratios. The absence of gDNA contamination in the samples was confirmed in the control experiments, in which reverse transcriptase was omitted (data not shown). Thermal cycling conditions were 95°C/10 min, 45 cycles 95°C/15 sec, 60°C/1 min. A quantification was done on a 7500 Real-time PCR System (Life Technologies) and the data were collected with the 7500 System SDS Software. All samples were done in duplicate.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and cloning of IFN-α fragments

The total RNA was extracted from MRC-5 cells, 24 h after infection using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed using MuLV reverse transcriptase and Oligo(dT) primers (both from Applied Biosystems). cDNA was amplified in 50 μL reaction using consensus primers designed to recognize all human IFN-α subtypes (sense 5′-GTACTGCAGAATCTCTCCTTTCTCCTG-3′ and antisense 5′-GTGTCTAGATCTGACAACCTCCCAGGGCACA-3′) (17) and Fidely Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The primers contained a PstI and XbaI restriction enzyme recognition site, respectively. The PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 68°C for 1 min 30 sec, followed by final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified IFN-α fragments were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified with the QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and cloned into the pUC19 plasmid using PstI and XbaI enzymes. After transformation of competent Escherichia coli DH5α with obtained plasmids, positive clones were picked based on blue-white selection, grown overnight, and the purified plasmids were sequenced. The entire procedure of infection, amplification, and cloning was performed three times.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis

The sequencing reactions were set up with purified plasmid DNA, specific primer used in PCR, and the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Sequencing and analysis of sequences were performed on a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The obtained sequences were identified by BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). From three independent experiments, 91, 78, and 66 complete IFN-α sequences were obtained for JL5 and 92, 67, and 42 IFN-α sequences for 9218/Zg98 infection. The differences in the induction of IFN-α subtypes were evaluated by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and considered significant for p<0.05.

IFN reporter gene assay

IFN reporter gene assay was adapted from Smilović et al. (34). The assay uses CHO-ISRE-SEAP cells, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells stably transfected with the secretory alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene under the control of IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) promoter. The cells were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates at 1×104 cells in 0.1 mL of F-12K medium (Sigma) containing 10% FCS and incubated overnight at 37°C. Twofold serial dilutions of reference reagent for native human IFN (Institute of Immunology, Inc.) were prepared in separate microtiter plates in triplicates. The samples (supernatants of infected cells previously UV inactivated for 5 min) were diluted the same way as the reference reagent. Hundred microliters of each dilution was transferred to the assay plates, and cells were incubated for 40 h at 37°C. Hundred microliters of supernatant from each well was added to the same volume of p-nitrophenol phosphate (pNPP) substrate (Sigma). The plates were incubated for one more hour and the absorbance was read at 405 nm on the Multiskan Spectrum spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). IFN potencies were obtained from dose–response curves using SkanIt Software 2.4.2. (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The differences in IFN quantities were evaluated by Student's t-test.

Analysis of antiviral activity of IFN-α subtypes

A549 were seeded in the DMEM containing 10% FCS and 50 μL/mL neomycin. The next day, the media were removed and cells were treated for 5 h with 500 IU of different IFN-α subtypes (PBL Biomedical Laboratories) or human recombinant IFN-α2a (AbDSerotec) prepared in the DMEM containing 50 μL/mL neomycin. Mock-treated cells were included as control. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and infected with MuV at MOI 0.1 or 1. One hour following adsorption at 35°C, virus was removed, cells were washed twice with PBS, and overlaid with fresh DMEM containing 2% FCS and 50 μL/mL neomycin. Two or three days after infection, the supernatants were collected for titer determination by PFU assay, as described in Forcic et al. (10). The differences in the antiviral activity were evaluated by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and considered significant for p<0.05.

Western blot analysis

A549 cells were mock infected or infected with MuV and lysed at 24, 48, or 72 h p.i. for 30 minutes on ice in a buffer (45 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 1% Igepal (Sigma)) containing the complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). Eighty μg of each sample was denaturated and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer onto Hybond-P membrane (GE Healthcare) and blocking with 5% skimmed milk. The rat polyclonal anti-(P/V) antibody was used diluted 1:500. As an input control, the goat polyclonal anti-beta actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used diluted 1:500. Appropriate species-specific alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used diluted 1:5,000. Proteins were detected using the ECF substrate (GE Healthcare) and filmed by Kodak Image Station 440CF and Kodak software (Kodak).

Results

Differences in the induction of IFN between MuV strains

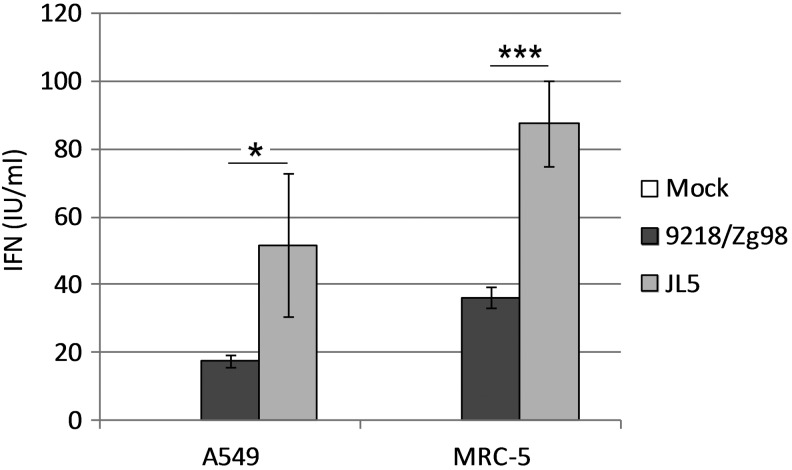

The human respiratory tract is a primary site for MuV replication and activation of early host defense mechanisms. To examine the induction of IFN in response to MuV infection, we infected normal human lung fibroblasts (MRC-5) and the human adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line (A549) with two MuV strains, JL5 and 9218/Zg98. Biologically active type I and type III IFNs released from MuV-infected cells were quantified using the CHO-ISRE-SEAP reporter cell line. Although infection with both viruses stimulated the production of IFN compared to mock-infected cells, the amount of IFN produced depended on a MuV strain. The JL5 strain induced significantly more IFN than the 9218/Zg98 strain in both A549 (p=0.031162) and MRC-5 cells (p=0.000002) (Fig. 1). In addition, we observed a difference in responsiveness between the two cell lines; MRC-5 cells produced more IFN than A549 cells with statistical significance for the JL5 (p=0.005152) and 9218/Zg98 strains (p=0.000036).

FIG. 1.

Production of interferons (IFNs) in cells infected with mumps virus (MuV). A549 or MRC-5 cells were mock infected or infected with 9218/Zg98 or JL5 viruses at MOI 3. Supernatants were collected at 72 h postinfection, and IFN (IU/mL) was assayed using the CHO-ISRE-SEAP reporter cell line. Each bar represents the mean of two samples measured in triplicate±standard deviation. Statistically significant differences between the groups are indicated by * for p<0.05, *** for p<0.0005 (student's t-test). One of three experiments is shown.

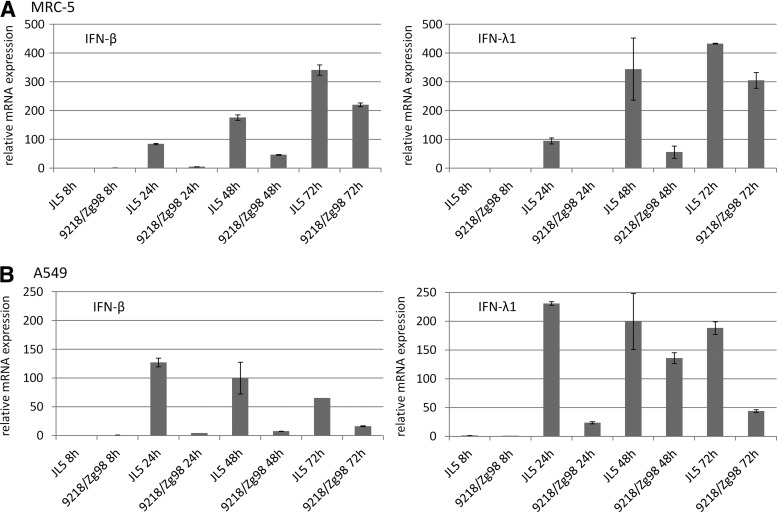

To determine if the observed difference is evident for induction of both type I and type III IFNs, we measured the expression of IFN-β as a predominant type I IFN and IFN-λ1 as a representative of type III IFN. Consistent with bioassay results, the JL5 strain stimulated higher expression of both IFN-β and IFN-λ1 at all time points after infection and in both cell lines than the 9218/Zg98 strain (Fig. 2A, B).

FIG. 2.

Induction of IFNB1 and IFNL1 genes in cells infected with MuV. Relative expression of mRNA was measured at 8, 24, 48, and 72 h after infection of MRC-5 (A) or A549 cells (B) by quantitative PCR. Obtained values were normalized against housekeeping gene (GAPDH) and then against the value of the sample with the lowest gene expression (9218/Zg98 8 h or JL5 8 h).

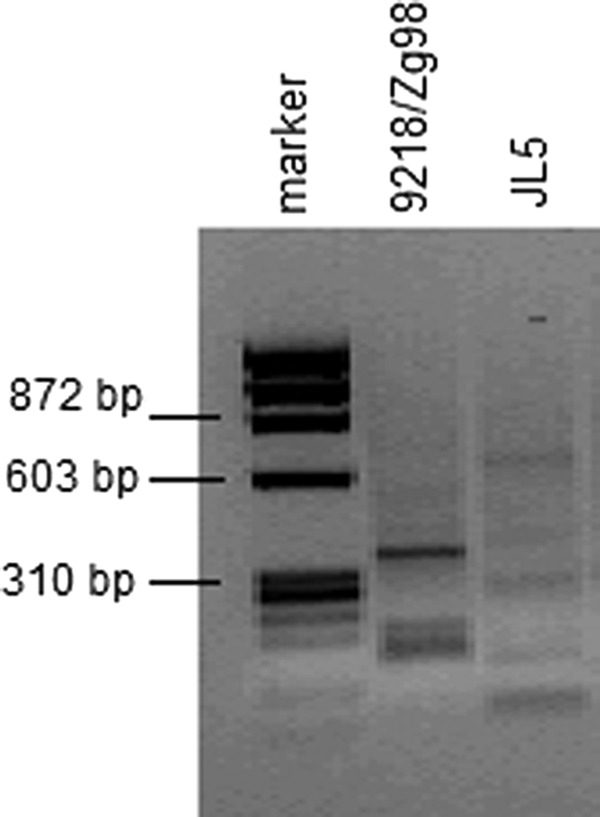

To examine if this difference in IFN-inducing abilities is a result of virus per se or can be attributed to the presence of DIPs, known as potent activators of IFN response, we next analyzed the content of DIPs in our virus suspensions by RT-PCR. Surprisingly, both viruses were found to contain DIPs with a strain-specific structure (Fig. 3). Therefore, one can assume that observed differences in IFN activation between the virus strains cannot be ascribed to the presence of DIPs. However, the potential role of specific species of DIPs in IFN activation cannot be excluded and this question will be addressed in our future studies.

FIG. 3.

Characterization of the content of defective interfering particles in the MuV suspensions by the RT-PCR method.

Induction of IFN-α subtypes in response to MuV infection

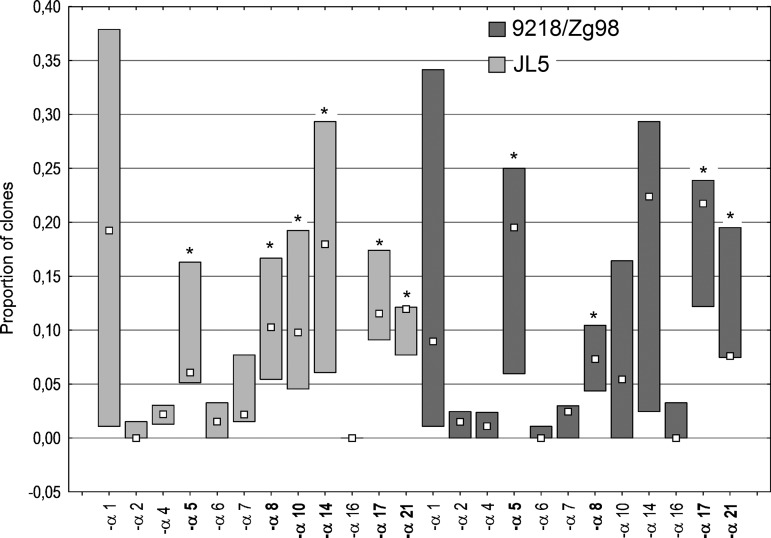

Having demonstrated a difference at the level of type I and type III IFN production in response to infection with two MuV strains, we have next focused on the expression of specific IFN-α subtypes following infection with these viruses. Our approach was to determine a proportion of a specific IFN-α mRNA in total RNA pool extracted from MRC-5 cells 24 h p.i. with JL5 and 9218/Zg98. Following amplification of the entire IFN-α population in a sample, we have cloned PCR fragments and analyzed sequenced clones. The results are expressed as the proportion of the clones representing each specific IFN-α subtype (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Induction of IFNA genes in cells infected with MuV. Total RNA was extracted from MRC-5 cells 24 h postinfection with 9218/Zg98 or JL5 virus at MOI 1, mRNA was reverse transcribed and DNA sequences of all IFN-α subtypes present in the obtained cDNA pool were amplified using consensus primers. The IFN-α amplicons were resolved by electrophoresis, purified, and cloned into pUC19 plasmids. The DNA sequences obtained were compared with sequences of individual IFNA genes in the GenBank provided by NCBI. The results are expressed as the proportion of the clones representing each specific IFN-α subtype. A median for each subtype group from three independent infections and cloning procedures is indicated by a square. Statistically significant differences between each subtype and IFN-α2 (for each MuV strain independently) are indicated by * for p<0.05.

We have found that all 12 IFN-α subtypes are expressed in infection with both virus strains. In addition, the pattern of their expression was highly similar between the virus strains. The only exception was IFN-α16, which emerged in only one of the three experiments (with low relative abundance) following infection with 9218/Zg98, whereas it was not at all expressed in response to JL5 infection.

Furthermore, we performed the analysis of expression of IFN-α subtypes for each virus strain independently by comparing the induction of each subtype to IFN-α2, which was characterized by low expression and small variance. The analysis revealed several subtypes that could be distinguished as weakly expressed for both the MuV strains (IFN-α2, -α4, -α6, -α7, and -α16). Adversely, a few more strongly expressed subtypes were found for both the MuV strains (IFN-α5, -α8, -α17, and -α21) and additionally, IFN-α10 and IFN-α14 for the JL5 strain. IFN-α1 was left out of analysis due to the great variance in results.

Sensitivity of MuV strains to specific IFN-α subtypes

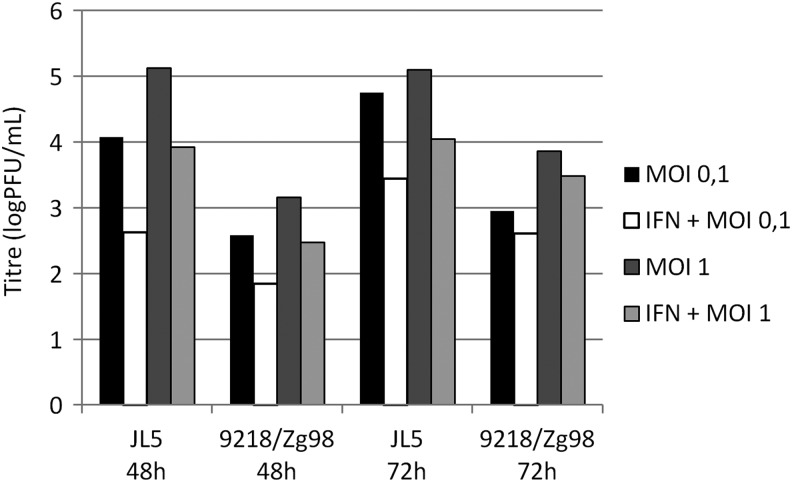

To be able to determine the effect that IFN-α subtypes have on MuV replication, we first sought for infection conditions that result in high titer of both viruses. To this end were tested infection of A549 and MRC-5 cells at two MOIs (0.1 and 1) and determined virus titers in cell culture supernatants at 48 and 72 h after infection. The MRC-5 cells did not support sufficient growth of 9218/Zg98 strain (<1 PFU/mL, data not shown), whereas A549 cells were more susceptible for replication of both viruses. As depicted in Figure 5, at each time point and with both MOIs, infection of A549 with JL5 yielded at least 1 log more virus than did infection with 9218/Zg98. While JL5 reached the highest titer with MOI 1 at both time points (5.1 PFU/mL), the highest titer in infection with 9218/Zg98 was obtained with MOI 1 at 72 h after infection (3.86 PFU/mL) (Fig. 5). We then measured the virus titer in the supernatants of A549 cells treated with recombinant human IFN-α2a before infection. Although JL5 replication was more affected by IFN treatment, approximately the same extent of inhibition was measured with both MOIs and at both time points after infection.

FIG. 5.

Determination of infection conditions for assessment of IFN-α antiviral activity. A549 cells were pretreated with 500 IU of recombinant human IFN-α2a or only with medium for 5 h and then infected with 9218/Zg98 or JL5 virus at MOI 0.1 or 1. The supernatants were collected at 48 or 72 h after infection and virus titer was determined by the PFU test.

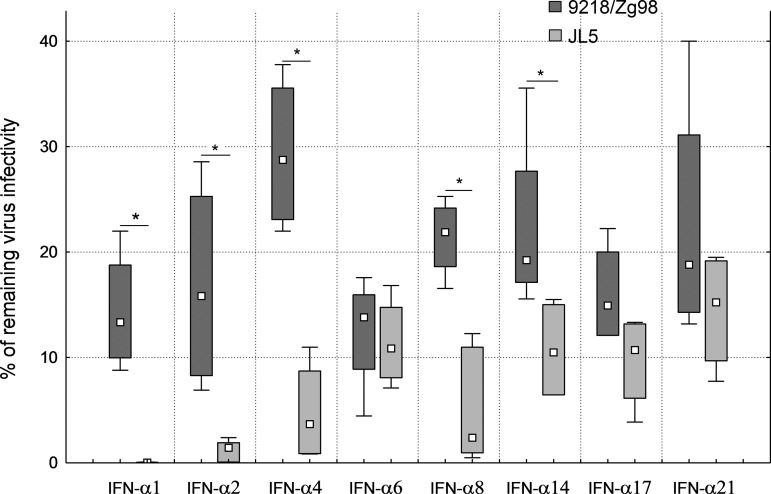

Based on these results, we decided to test the antiviral activity of several IFN-α subtypes on MuV replication 72 h after infection of A549 cells at MOI 1.The results are expressed as the percentage of virus survival in cells pretreated with certain IFN-α subtypes compared with untreated cells (Fig. 6). All tested IFN-α subtypes were active against both virus strains. The mean percentages of remaining virus infectivity were between 10% and 30% for the 9218/Zg98 strain. The IFN-α6 exhibited the strongest antiviral effect on 9218/Zg98, whereas IFN-α4 was the least active among the tested subtypes.

FIG. 6.

MuV sensitivity to IFN-α subtypes. A549 cells were pretreated with 500 IU of different IFN-α subtypes or only with medium for 5 h and then infected with 9218/Zg98 or JL5 virus at MOI 1. The supernatants were collected at 72 h after infection and virus titer was determined by the PFU test. Two independent experiments were performed with at least duplicate infections. The results are given as the percentage of virus infectivity remaining after each treatment compared to the virus titer in untreated infected cells. A median for each group is shown by square, the upper and lower quartiles are shown with boxes, and minimum and maximum values are indicated by whiskers. Statistically significant differences between MuV strains are indicated by * for p<0.05.

The JL5 strain was generally more sensitive to IFN-α subtypes than 9218/Zg98 with up to only 15% of the mean virus infectivity remaining after the IFN treatment. The statistically significant increase in sensitivity compared to the 9218/Zg98 strain was found for the following subtypes: IFN-α1, IFN-α4, and IFN-α14 (p=0.020922), IFN-α2 and IFN-α8 (p=0.010516). Interestingly, IFN-α1 completely abolished JL5 replication and treatment with IFN-α2 left only 2% of its infectivity. Thus, the intensity of the overall IFN antiviral activity as well as the activity of specific IFN-α subtypes depends on a virus strain.

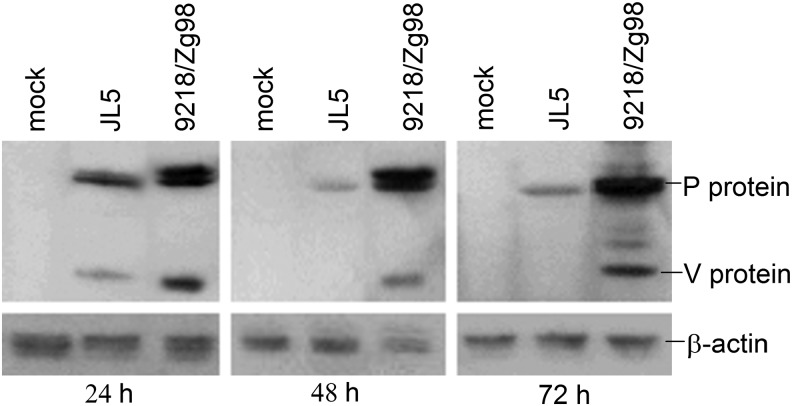

To check for potential differences between V proteins of our MuVs, which might contribute strain-specific IFN sensitivity, we examined the kinetics of V protein expression following infection of A549 cells. The western blot analysis of cell lysates clearly showed that V protein expression differed between the virus strains; it was detected only early after infection with JL5 (24 h.p.i.), whereas it was more abundant in infection with 9218/Zg98, at all time points tested (Fig. 7). This stronger V protein expression might, at least partially, explain the weaker sensitivity of 9218/Zg98 to treatment with IFN-α subtypes in comparison to JL5 (Fig. 6) as well as less IFN production (Fig. 1).

FIG. 7.

Expression of MuV V protein in infected cells. A549 cells were mock infected or infected with 9218/Zg98 or JL5 viruses at MOI 1. The amounts of P and V proteins (detected with the rat polyclonal anti-[P/V] antibody) and actin beta (detected with the polyclonal anti-beta actin antibody) as an input control were measured by western blot in the cell lysates at 24, 48, or 72 h p.i.

Discussion

At the early stage of virus infection, a strong and effective response of multiple type I IFNs, predominantly IFN-α and IFN-β, is raised within a host at the primary sites of virus infection, prevailing an uncontrolled virus replication. The human IFN-α family consists of 12 highly homologous IFN-α proteins encoded by 13 IFNA genes. An evolutionary advantage of keeping a large set of these IFNs and a role for specific IFN-α subtypes in the context of virus infection is still an intriguing question. Additionally, the question remains whether there is a difference among virus strains at both the level of induction of IFN-α subtypes and at the level of their specific antiviral activity.

So far, only few studies have explored an expression and/or antiviral activity of specific IFN-α subtypes employing in vitro and in vivo models of virus infection [reviewed in Gibbert et al. (12)]. Some of these studies trying to correlate the type of stimulus with a specific pattern of IFN-α subtype expression have brought contradictious results. Baig and Fish (4) reported both expression and activity of IFN-α subtypes on mouse embryonic fibroblasts following infection with mouse hepatitis virus, Sendai virus, or Coxsackie B3 virus to be virus dependent. Likewise, it was shown that a type of stimulus governs IFN-α expression patterns in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (13). On the other hand, studies using pDCs, which are primary IFN-α producers, and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells demonstrated that relative abundance of specific IFN-α subtypes remains the same regardless of the stimulus used (e.g., CpG oligonucleotides, live and inactivated influenza virus, Toll-like receptor 9 agonist, Newcastle disease virus, hepatitis virus, or respiratory syncytial virus) (23,36).

The subject of our study was MuV, a paramyxovirus, whose only natural host is human. A primary site for mumps infection is the respiratory tract; therefore, we used human lung cell lines to analyze the expression profile of IFN-α subtypes in response to infection with different MuV strains. The approach used herein for the identification of IFN-α subtype transcripts in infected cells consisted of PCR amplification of all IFN-α subtypes using universal primers and subsequent cloning of PCR products and sequencing. This methodology has previously been used successfully for characterization of IFN-α subtypes arising in virally stimulated cells (7,17,27). We found that JL5 and 9218/Zg98 MuV strains in MRC-5 cells evoke a similar IFN-α pattern without any statistical differences between the virus strains.

All 12 subtypes were expressed except IFN-α16, which was weakly induced in one of three experiments in 9218/Zg98 infection but not induced in JL5 infection. In addition, IFN-α subtypes could be classified into two groups: weakly induced (IFN-α2, -α4, -α6, -α7, and -α16) and more strongly induced subtypes (IFN-α5, -α8, -α17, -α21 for both viruses and additionally IFN-α10 and IFN-α14 for the JL5 strain). This classification was made by comparison of induction of certain IFN-α subtypes to the induction of IFN-α2. The comparison of expression of IFN-α1 (for both viruses) and -α10 and -α14 (for 9218/Zg98) was not possible due to the higher variance in their induction.

When the amounts of IFN proteins produced by infected MRC-5 cells as well as A549 were compared, a significant difference between JL5 and 9218/Zg98 MuV strains was seen (Fig. 1). The observed difference cannot be ascribed to differential kinetics of IFN protein synthesis as no IFN could be measured at earlier time points after infection nor the IFN ratio between two strains changed at later time points (data not shown). The difference between the JL5 and 9218/Zg98 MuV strains was also confirmed at the level of mRNA expression for IFN-β (type I IFN) and IFN-λ1 (type III IFN). Although type III IFN was not in the focus of our interest, knowing its involvement in the protection of respiratory epithelium (2), our data suggest that it might play a role in early response to MuV infection as well.

For measles virus, another member of the Paramyxoviridae family, a correlation between the attenuation level and ability to induce type I IFN has been repeatedly demonstrated (26,32). Attenuated vaccine strains acted as stronger IFN stimulators compared to wild-type measles virus strains. Consistent with these observations, infection with the MuV vaccine strain (JL5) led to a more productive type I IFN response compared to the wild-type MuV strain (9218/Zg98). Previous studies have proposed some factors responsible for strong versus weak type I IFN response in paramyxovirus infection such as differences in the viral accessory V proteins with IFN-antagonistic activity (37) or the presence of DIPs in virus suspension (19,33,35). We found that sequences of the V proteins of our two MuVs differ at 13 amino acid residues (amino acid 27, 39, 41, 59, 64, 69, 76, 78, 80, 83, 86, 88, and 108), none of which is located in the conserved C-terminal part of the protein where positions critical for IFN antagonistic functions are located (data not shown). Our data also showed that two V proteins are being expressed with different intensities, suggesting that a stronger V protein expression in the case of 9218/Zg98 might be responsible for more restrained IFN production. In addition, we found that each MuV contains different species of copy-back DIPs. We are currently addressing, in more detail, factors that cause discrepancies in the ability of various MuV strains to induce IFN.

A distinct antiviral activity of IFN-α subtypes has been reported for several RNA viruses like human metapneumovirus (31), influenza virus (25), and vesicular stomatitis virus (18,31). To examine if this is true in the case of MuV as well as to check if the antiviral activity of specific IFN-α subtypes varies depending on a virus strain, we pretreated A549 cells with several IFN-α subtypes and compared their potencies against infection with two MuVs. We found that all tested IFN-α subtypes were effective in suppressing replication of both the MuV strains. However, neither the pattern of their activity nor intensity of their action was equal for MuV strains. The overall sensitivity to IFN-α subtypes for each strain positively correlated with the amount of IFN produced in response to the same virus strain (Fig. 1) and negatively correlated with the amount of V protein in infected cells (Fig. 7).

An influence of a cell type on IFN-α expression patterns has also been debated. Baig and Fish (4) demonstrated that murine IFN expression profiles differed according to whether the IFN was expressed by lung fibroblast cell lines or tissue stimulated in vivo. Similarly, murine cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts were reported to express different IFN-α subtypes in response to reovirus (22). On the other hand, a study of Easlick and coworkers (9) demonstrated that relative IFN-α expression patterns are identical irrespective of the cellular background. Additionally, high consistency in antiviral gene induction by specific IFN-α proteins was demonstrated for primary fibroblasts and endothelial cells of vascular or lymphatic origin (25). Although we expect similar relative IFN-α subtype expression profiles between A549 and MRC-5 cell lines, the possibility that they might differ cannot be excluded and therefore needs further investigation.

In conclusion, we found that the entire range of IFN-α subtypes is expressed in response to MuV infection and that the intensity of overall IFN antiviral activity as well as the activity of specific IFN-α subtypes depends on a virus strain.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Smilović (National Institute of Chemistry, Ljubljana, Slovenia) and B. K. Rima (School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences, Queen's University of Belfast, United Kingdom) for providing CHO-ISRE-SEAP reporter cells and JL5 MuV strain, respectively. This work was supported by the Ministry of science, education and sports of the Republic of Croatia, grant #021-0212432-3123 (to M.Š).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Andrejeva J, Childs KS, Young DF, et al. The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, mda-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN-β promoter. PNAS 2004;101:17264–17269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ank N, West H, Bartholdy C, Eriksson K, Thomsen AR, and Paludan SR. Lambda interferon (IFN-λ), a type III IFN, is induced by viruses and IFNs and displays potent antiviral activity against select virus infections in vivo. J Virol 2006;80:4501–4509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Au WC, Moore PA, LaFleur DW, Tombal B, and Pitha PM. Characterization of the interferon regulatory factor-7 and its potential role in the transcription activation ofinterferon A genes. J Biol Chem 1998;273:29210–29217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baig E, and Fish EN. Distinct signature type I interferon responses are determined by the infecting virus and the target cell. Antivir Ther 2008;13:409–422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branovic K, Forcic D, Ivancic J, et al. Application of short monolithic columns for improved detection of viruses. J Virol Methods 2003;110:163–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calain P, Curran J, Kolakofsky D, and Roux L. Molecular cloning of natural copy-back defective interfering RNAs and their expression from DNA. Virol 1992;191:62–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castelruiz Y, Larrea E, Boya P, Civeira MP, and Prieto J. Interferon alfa subtypes and levels of type I interferons in the liver and peripheral mononuclear cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C and controls. Hepatology 1999;29:1900–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dayan GH, and Rubin S. Mumps outbreaks in vaccinated populations: are available mumps vaccines effective enough to prevent outbreaks? Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:1458–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Easlick J, Szubin R, Lantz S, Baumgarth N, and Abel K. The early interferon alpha subtype response in infant macaques infected orally with SIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:14–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forcic D, Kosutić-Gulija T, Santak M, et al. Comparisons of mumps virus potency estimates obtained by 50% cell culture infective dose assay and plaque assay. Vaccine 2010;28:1887–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Génin P, Vaccaro A, and Civas A. The role of differential expression of human interferon-a genes in antiviral immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2009;20:283–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbert K, Schlaak JF, Yang D, and Dittmer U. IFN-α subtypes: distinct biological activities in anti-viral therapy. Br J Pharmacol 2013;168:1048–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillyer P, Mane VP, Schramm LM, et al. Expression profiles of human interferon-alpha and interferon-lambda subtypes are ligand- and cell-dependent. Immunol Cell Biol 2012;90:774–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honda K, Takaoka A, and Taniguchi T. Type I interferon gene induction by the interferon regulatory factor family of transcription factors. Immunity 2006;25:349–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, et al. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature 2005;434:772–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hviid A, Rubin S, and Mühlemann K. Mumps. Lancet 2008;371:932–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izaguirre A, Barnes BJ, Amrute S, et al. Comparative analysis of IRF and IFN-alpha expression in human plasmacytoid and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol 2003;74:1125–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaks E, Gavutis M, Uzé G, Martal J, and Piehler J. Differential receptor subunit affinities of type I interferons govern differential signal activation. J Mol Biol 2007;366:525–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Killip MJ, Young DF, Gatherer D, et al. Deep sequencing analysis of defective genomes of parainfluenza virus 5 and their role in interferon induction. J Virol 2013;87:4798–4807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota T, Yokosawa N, Yokota S, and Fujii N. C-terminal CYS-RICH region of mumps virus structural V protein correlates with block of interferon alpha and gamma signal transduction pathway through decrease STAT1-alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001;283:255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubota T, Yokosawa N, Yokota S, Fujii N, Tashiro M, and Kato A. Mumps virus V protein antagonizes interferon without the complete degradation of STAT1. J Virol 2005;79:4451–4459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L, and Sherry B. IFN-alpha expression and antiviral effects are subtype and cell type specific in the cardiac response to viral infection. Virology 2010;396:59–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Löseke S, Grage-Griebenow E, Wagner A, Gehlhar K, and Bufe A. Differential expression of IFN-alpha subtypes in human PBMC: evaluation of novel real-time PCR assays. J Immunol Methods 2003;276:207–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu LL, Puri M, Horvath CM, and Sen GC. Select paramyxoviral V proteins inhibit IRF3 activation by acting as alternative substrates for inhibitor of kappaB kinase epsilon (IKKe)/TBK1. J Biol Chem 2008;283:14269–14276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moll HP, Maier T, Zommer A, Lavoie T, and Brostjan C. The differential activity of interferon-alpha subtypes is consistent among distinct target genes and cell types. Cytokine 2011;53:52–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naniche D, Yeh A, Eto D, Manchester M, Friedman RM, and Oldstone MB. Evasion of host defenses by measles virus: wild-type measles virus infection interferes with induction of alpha/beta interferon production. J Virol 2000;74:7478–7484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer P, Tovey MG, Raschilas F, et al. Type I interferon subtypes produced by human peripheral mononuclear cells from one normal donor stimulated by viral and non-viral inducing factors. Eur Cytokine Netw 2007;18:108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pestka S, Krause CD, and Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev 2004;202:8–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randall RE, and Goodbourn S. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signaling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J Gen Virol 2008;89:1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santak M, Kosutić-Gulija T, Tesović G, et al. Mumps virus strains isolated in Croatia in 1998 and 2005: genotyping and putative antigenic relatedness to vaccine strains. J Med Virol 2006;78:638–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scagnolari C, Trombetti S, Selvaggi C, et al. In vitro sensitivity of human metapneumovirus to type I interferons. Viral Immunol 2011;24:159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shingai M, Ebihara T, Begum NA, et al. Differential type I IFN-inducing abilities of wild-type versus vaccine strains of measles virus. J Immunol 2007;179:6123–6133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shivakoti R, Siwek M, Hauer D, Schultz KL, and Griffin DE. Induction of dendritic cell production of type I and type III interferons by wild-type and vaccine strains of measles virus: role of defective interfering RNAs. J Virol 2013;87:7816–7827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smilović V, Caserman S, Fonda I, Gaberc-Porekar V, and Menart V. A novel reporter gene assay for interferons based on CHO-K1 cells. J Immunol Methods 2008;333:192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strahle L, Garcin D, and Kolakofsky D. Sendai virus defective-interfering genomes and the activation of interferon-beta. Virology 2006;351:101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szubin R, Chang WL, Greasby T, Beckett L, and Baumgarth N. Rigid interferon-alpha subtype responses of human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2008;28:749–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takaki H, Watanabe Y, Shingai M, Oshiumi H, Matsumoto , and Seya T. Strain-to-strain difference of V protein of measles virus affects MDA5-mediated IFN-β-inducing potential. Mol Immunol 2011;48:497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]