Abstract

The development of an H2N2 vaccine is a priority in pandemic preparedness planning. We previously showed that a single dose of a cold-adapted (ca) H2N2 live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) based on the influenza A/Ann Arbor/6/60 (AA ca) virus was immunogenic and efficacious in mice and ferrets. However, in a Phase I clinical trial, viral replication was restricted and immunogenicity was poor. In this study, we compared the replication of four H2N2 LAIV candidate viruses, AA ca, A/Tecumseh/3/67 (TEC67 ca), and two variants of A/Japan/305/57 (JAP57 ca) in three non-human primate (NHP) species: African green monkeys (AGM), cynomolgus macaques (CM) and rhesus macaques (RM). One JAP57 ca virus had glutamine and glycine at HA amino acid positions 226 and 228 (Q-G) that binds to α2-3 linked sialic acids, and one had leucine and serine that binds to α2-3 and α2-6 linked residues (L-S). The replication of all ca viruses was restricted, with low titers detected in the upper respiratory tract of all NHP species, however replication was detected in significantly more CMs than AGMs. The JAP57 ca Q-G and TEC67 ca viruses replicated in a significantly higher percentage of NHPs than the AA ca virus, with the TEC67 ca virus recovered from the greatest percentage of animals. Altering the receptor specificity of the JAP57 ca virus from α2-3 to both α2-3 and α2-6 linked sialic acid residues did not significantly increase the number of animals infected or the titer to which the virus replicated. Taken together, our data show that in NHPs the AA ca virus more closely reflects the human experience than mice or ferret studies. We suggest that CMs and RMs may be the preferred species for evaluating H2N2 LAIV viruses, and the TEC67 ca virus may be the most promising H2N2 LAIV candidate for further evaluation.

Keywords: H2N2, influenza, vaccine, LAIV, non-human primate, monkey

1. Introduction

In 1957, a novel influenza A virus of the H2N2 subtype emerged in humans and led to a pandemic associated with an estimated 1 to 4 million deaths worldwide [1]. This subtype circulated until 1968, when it was replaced in a pandemic caused by the H3N2 virus [2]. Influenza viruses of the H2N2 subtype have not circulated in the human population since [3], and consequently individuals born after 1968 do not possess antibodies to H2N2 viruses and are susceptible to infection [4]. In contrast, H2 influenza viruses continue to be isolated from migratory birds, poultry and swine [5-10], and the H2N2 viruses isolated from birds have a high degree of genetic and antigenic similarity to viruses that contributed genes to the 1957 pandemic virus [11,12]. Due to the continued presence of H2N2 viruses in animal populations, the demonstrated ability of this subtype to cause a pandemic, and the waning immunity in the human population as the proportion of seronegative people increases, there remains an unmet need for vaccines against H2N2 influenza viruses.

In order to meet this need, the efficacy of the A/Ann Arbor/6/60 cold-adapted (ca) H2N2 virus (AA ca) as a live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) was evaluated in mice and ferrets. The vaccine virus replicated well, was immunogenic, and a single dose provided complete protection against lethal homologous challenge, and significant protection from heterologous challenge with A/Swine/MO/4296424/2006 (H2N3), A/Japan/305/1957 (H2N2) and A/Mallard/NY/6750/78 (H2N2) [13]. Given these promising preclinical data, a Phase I clinical trial was conducted. However, the vaccine virus was found to be restricted in replication, with virus only detected in 24% and 17% of inoculated subjects by culture or RT-PCR after the first and second doses, respectively. In addition, the vaccine was poorly immunogenic, with only 24% of participants developing an antibody response measured by hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) or ELISA after either one or two doses [14].

In order to select alternative H2N2 LAIV candidates, a geographically and temporally diverse group of wild-type H2 influenza viruses were evaluated for their ability to induce immune responses in mice and ferrets that cross-reacted with heterologous H2 influenza viruses. The A/Japan/305/57 virus was found to elicit broadly cross-reactive antibody responses [15], and a cold-adapted LAIV candidate was generated with six internal protein gene segments from the AA ca virus and the HA and NA genes from the A/Japan/305/57 virus (JAP57 ca). However, the hemagglutinin (HA) protein of the egg-propagated JAP57 ca virus contained a glutamine (Q) residue at amino acid position 226 and glycine (G) at position 228, and preferentially bound sialic acids with a terminal α2-3 link to galactose, which are less common in the upper respiratory tract (URT) of humans than α2-6 linked sialic acids [16]. With the view of optimizing the replication of candidate H2N2 LAIV for clinical use, the receptor binding preference of the HA was altered to one that bound both α2-3 and α2-6 linked sugar residues by the mutation of Q to leucine (L), and G to serine (S). The resultant virus, JAP57 ca L-S, replicated to higher titers in the upper respiratory tract of ferrets than the JAP57 ca Q-G virus, induced a higher homologous geometric mean antibody titer, and was more protective against heterologous challenge with wt influenza A/mallard/New York/6750/78 (H2N2) [17], suggesting that it may also be a better candidate vaccine virus for humans than the AA ca or JAP57 ca Q-G viruses.

Because small animal models were not predictive of the findings in clinical trials for the AA ca virus, we sought to investigate the use of non-human primates (NHPs) to evaluate H2N2 LAIV virus replication, in order to better inform the selection of an H2N2 LAIV candidate for further evaluation in phase I clinical trials. African green monkeys (AGM, Chlorocebus aethiops) and rhesus macaques (RM, Macaca mulatta) have previously been used to evaluate the replication of cold adapted LAIV viruses [18,19], and cynomolgus macaques (CM, Macaca fascicularis) have been used to study the pathogenesis of H5N1, 1918 H1N1 and 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza viruses [20-25]. We therefore evaluated the replication of the AA ca, JAP57 ca Q-G, and JAP57 ca L-S viruses in AGMs, RMs and CMs.

Both the Japan/305/1957 and Ann Arbor/6/60 viruses have been extensively passaged in eggs and mutations in the HA gene may have arisen that potentially restrict the replication of the ca LAIV candidates in people. Therefore, we sought a low passage H2N2 virus isolate, and obtained a frozen throat swab sample from which the H2N2 influenza A/Tecumseh/3/67 (TEC67) virus had been isolated in 1967 [26]. The TEC67 HA and NA genes were amplified and sequenced from RNA, and a TEC67 ca virus was generated by reverse genetics with the six internal protein genes from the AA ca virus and the HA and NA genes from the TEC67 virus. The replication of the TEC67 ca virus was also evaluated in AGMs, CMs and RMs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Viruses

The AA ca, JAP57 ca Q-G and JAP57 ca L-S candidates were generated by reverse genetics as previously described [13,17]. The TEC67 virus RNA was obtained from a frozen throat swab sample that was kindly provided by Dr. Arnold Monto, University of Michigan. The HA and NA gene segments of TEC67 were amplified by RT-PCR, cloned into the reverse genetics vector, and a 6:2 reassortant TEC67 ca virus was generated by eight-plasmid transfection with the HA and NA gene segments from TEC67 and the six internal protein gene segments from AA ca. Three amino acid substitutions (K131T, D133T and K197N) were introduced into the HA gene to allow TEC67 ca to grow efficiently in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells and embryonated chicken eggs. The viruses were propagated in 9-to-11 day old embryonated specific pathogen free chicken eggs, and the titer of each virus was determined in MDCK cells.

2.2. Non human primates

A total of 81 NHPs were used in this study: 24 CMs, 24 RMs, and 33 AGMs. Animals were approximately 3-4 years of age, and 40 were male and 41 were female. The animals originated from Indonesia (CMs), India (RMs), and St. Kitts (AGMs). The NHPs were examined daily for evidence of clinical illness such as body temperature, pulse, appetite, behavior, stool, respiratory symptoms and ocular signs. All animal experiments were done at NIH in compliance with the guidelines of the NIAID/NIH Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3. Immunization

Animals were anesthetized by intramuscular (i.m.) injection of Ketamine HCl (10mg/kg) and inoculated with candidate vaccine viruses at a concentration of 1 x 106 TCID50 /ml, 1 ml administered intranasally (i.n.) and 1ml intratracheally (i.t.).

2.4. Replication Studies

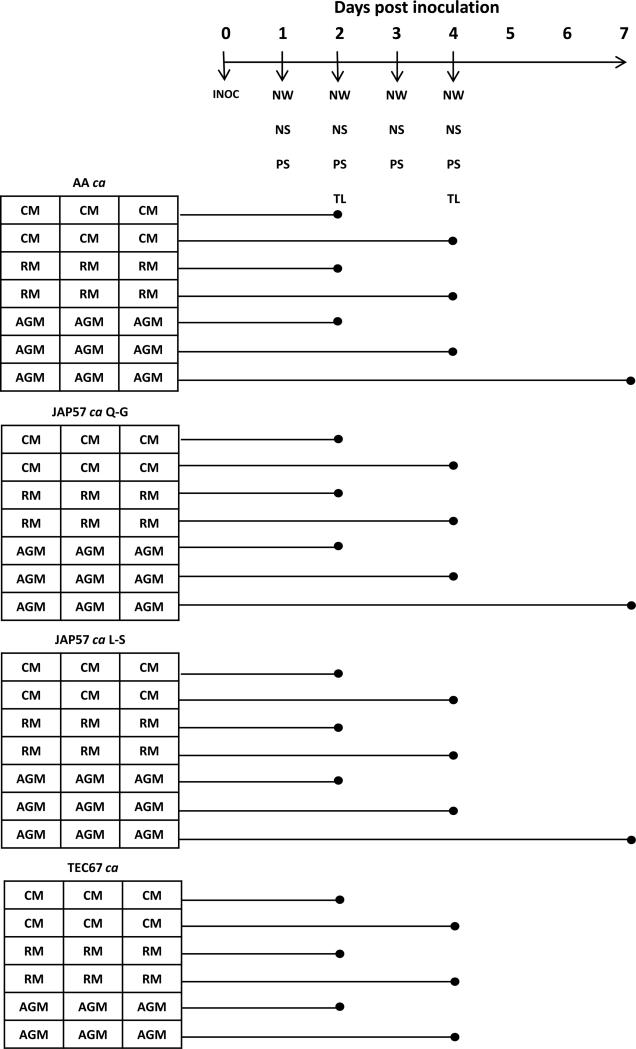

Groups of six CMs and six RMs were inoculated with AA ca, JAP57 ca, JAP57 ca L-S, and TEC67 ca viruses. Groups of nine AGMs were inoculated with AA ca, JAP57 ca, and JAP57 ca L-S viruses, and six AGMs were inoculated with the TEC67 ca virus (Figure 1). Nasal washes (NW), nasal swabs (NS), and pharyngeal swabs (PS) were collected daily following inoculation for four days. At days two and four post inoculation, a tracheal lavage (TL) was obtained from groups of three AGMs, three CMs and three RMs inoculated with the same virus, prior to euthanasia and necropsy. The nasal turbinates (NT), pharynx (P), larynx (L), trachea (T), and a section of the left and right lung were harvested at necropsy for viral titration. In addition, groups of three AGMs infected with AA ca, JAP57 ca, and JAP57 ca L-S viruses were also euthanized on day seven post-inoculation and organs harvested for viral titration (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Experimental Design.

Groups of three CMs, RMs, and AGMs were inoculated with the viruses AA ca, JAP57 ca, JAP57 ca L-S and TEC67 ca and euthanized on days 2, 4 or 7 post-infection for necropsy. At days 1-4 post inoculation, nasal wash (NW), nasal swab (NS), and pharyngeal swab (PS) samples were obtained, and at days 2 and 4 post inoculation, tracheal lavage (TL) samples were obtained. At necropsy, samples from the nasal turbinates, pharynx, larynx, trachea, and left and right lung were obtained for virus titration.

The NS and PS samples were placed into 1ml sterile PBS, pulse vortexed, and the NW, TL, NS and PS samples were titrated in 24- and 96- well tissue culture plates containing monolayers of MDCK cells. The cells were incubated at 33°C for 7 days, whereupon the presence of absence of cytopathic effect (CPE) in each well was determined. The dilution at which 50% of the wells were infected (TCID50) was computed using the Reed and Muench method [27], and titers were expressed as log10 TCID50 / ml sample.

The NT, P, L, T, and lung samples were homogenized in L-15 medium containing antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to make a 10% (weight /volume) tissue homogenate that was cleared by centrifugation and titrated as described above. The titer was computed, and expressed as log10 TCID50 / g tissue.

2.5. Statistics

A logistical regression model was used to analyze the relationship between infection status (infected Vs uninfected), NHP species, and virus.

3. Results

Groups of AGMs, CMs and RMs were inoculated with AA ca, JAP57 ca Q-G, JAP57 ca L-S, and TEC67 ca viruses. Each day, clinical signs were observed and the titer of virus in the secretions was determined. At two and four days post-inoculation, the titer of virus in the tissues was determined (Figure 1).

None of the animals developed clinical signs such as increased body temperature, weight loss, or signs of respiratory distress during the course of the study. In addition, virus was not detected in the lung samples (data not shown), consistent with the fact that the ca LAIV are temperature sensitive and shut off at the core body temperature of NHPs.

The replication of the H2N2 LAIV viruses was restricted in NHPs, with viruses only detected in 42/81 (52%) of animals (Table 1), and replicating to titers of 102.0 −105.2 TCID50/g of NT tissue (Table 2) and 101.0 −102.7 TCID50/ml NW fluid (Table 3). Viruses were recovered from a significantly higher percentage of CMs [16/24 (67%)] than AGMs [12/33 (36%)], p = 0.03, and a greater number of RMs [14/24 (58%)] than AGMs, though the latter did not reach statistical significance (p =0.13) (Table 1). LAIV were most consistently detected in the NT, with 23 samples testing positive for one or more virus, in contrast to the pharynx, larynx or trachea, where LAIV were only detected in five, four or two samples, respectively (Table 2). Consistent with this observation, 21 NW samples, and 20 nasal swab (NS) samples were positive for one or more virus (Table 3), in contrast to only four pharyngeal swab samples and three tracheal lavage samples (Table 4).

Table 1.

Virus replication in the upper respiratory tract of non-human primates

| NHP Species | Viruses |

Total (# culture positive / total (percentage)) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA ca (# culture positive / total (percentage)) | JAP57 ca Q-G (# culture positive / total (percentage)) | JAP57 ca L-S (# culture positive / total (percentage)) | TEC67 ca (# culture positive / total (percentage)) | ||

| CM | 3/6a(50)b | 3/6 (50) | 4/6 (67) | 6/6 (100) | 16/24 (67) |

| RM | 3/6 (50) | 3/6 (50) | 5/6 (83) | 3/6 (50) | 14/24 (58) |

| AGM | 0/9 (0) | 7/9 (78) | 2/9 (22) | 3/6 (50) | 12/33 (36) |

| Total | 6/21 (29) | 13/21 (62) | 11/21 (53) | 12/18 (67) | 42/81 (52) |

number of animals in which virus was detected in one or more samples from respiratory tissues at necropsy (NT, P, L, or T), or in secretion samples (NW, NS, PS and TL ) out of total number of animals

percentage of animals in which virus was detected

Table 2.

Virus replication in upper respiratory tract tissues of non-human primates

| Virus | NHP species | Days pi | Nasal turbinates | Pharynx | Larynx | Trachea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | |||

| AA ca | CM | 2 | 0/3a | NDb | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND |

| 4 | 1/3 | 2.0c | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 1/3 | 2.0 | ||

| RM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.5 | 1/3 | 2.5 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 2 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 7 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| JAP57 ca Q-G | CM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND |

| 4 | 1/3 | 5.2 | 0/3 | ND | 1/3 | 2.5 | 1/3 | 2.0 | ||

| RM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 2 | 2/3 | 2.0, 5.0 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 3/3 | 2.2 ± 0.2d | 0/3 | ND | 2/3 | 2.0, 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 7 | 0/3 | ND | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| JAP57 ca L-S | CM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND |

| 4 | 2/3 | 2.5, 2.5 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| RM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.5 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 2/3 | 2.5, 2.5 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 7 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| TEC67 ca | CM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND |

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| RM | 2 | 1/3 | 2.5 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 2 | 3/3 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0/3 | ND | 1/3 | 2.0 | 0/3 | ND | |

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

number of animals in which virus was detected from respiratory tissues at necropsy out of total number of animals

ND = none detected

individual titer of virus from influenza-positive samples (log10 TCID50/g tissue)

mean virus titer from influenza-positive samples (log10 TCID50/g tissue) ± standard error

Table 3.

Virus replication in upper respiratory tract secretions of non-human primates

| Virus | NHP species | Days pi | Nasal wash |

Nasal swab |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | |||

| AA ca | CM | 1 | 0/6a | NDb | 0/6 | ND |

| 2 | 1/6 | 2.2 | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 3 | 1/3 | 1.0 | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 4 | 2/3 | 1.0c, 1.7 | 2/3 | 1.7, 1.7 | ||

| RM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | |

| 2 | 1/6 | 1.0 | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/9 | ND | 0/9 | ND | |

| 2 | 0/9 | ND | 0/9 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 4 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | ||

| JAP57 ca Q-G | CM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 4 | 1/3 | 1.5 | 1/3 | 1.5 | ||

| RM | 1 | 1/6 | 1.0 | 0/6 | ND | |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 1/6 | 1.5 | ||

| 3 | 1/3 | 2.7 | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/9 | ND | 0/9 | ND | |

| 2 | 1/9 | 1.5 | 1/9 | 1.5 | ||

| 3 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 4 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | ||

| JAP 57 ca L-S | CM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | 1/6 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 1/6 | 1.5 | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 1/3 | 1.0 | ||

| RM | 1 | 2/6 | 1.0, 2.0 | 0/6 | ND | |

| 2 | 1/6 | 1.5 | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 3 | 1/3 | 1.0 | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 4 | 1/3 | 1.5 | 2/3 | 1.5, 1.5 | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/9 | ND | 0/9 | ND | |

| 2 | 0/9 | ND | 1/9 | 1.5 | ||

| 3 | 0/6 | ND | 1/6 | 1.0 | ||

| 4 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | ||

| TEC67 ca | CM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | 2/6 | 1.0, 0.8 |

| 2 | 2/6 | 2.2, 1.0 | 2/6 | 1.0, 2.2 | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | 3/3 | 1.7 ±0.3d | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| RM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | |

| 2 | 3/6 | 1.0 ±0 | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 3 | 1/3 | 1.5 | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | 1/6 | 1.7 | |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/6 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | 1/3 | 1.5 | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

number of samples in which virus was detected from respiratory secretions out of total number of samples

ND = none detected

individual titer of virus from influenza-positive samples (log10 TCID50/ml)

mean virus titer from influenza-positive samples (log10 TCID50/ml) ± standard error

Table 4.

Virus replication in pharyngeal swab and tracheal lavage samples of non-human primates

| Virus | NHP species | Days pi | Pharyngeal swab |

Tracheal lavage |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | # of culture positive/total | Individual or mean titer ± SE | |||

| AA ca | CM | 1 | 0/6a | NDb | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| RM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 1/3 | 1.0 | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/9 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 0/9 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| JAP57 ca Q-G | CM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| RM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/9 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 1/9 | 1.7d | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 1/6 | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| JAP57 ca L-S | CM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| RM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 1/6 | 1.0 | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 1/3 | 1.7 | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/9 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 1/9 | 1.5 | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 1/6 | 1.0 | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| TEC67 ca | CM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 1/3 | 2.5 | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| RM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| AGM | 1 | 0/6 | ND | N/A | N/A | |

| 2 | 0/6 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

| 3 | 0/3 | ND | N/A | N/A | ||

| 4 | 0/3 | ND | 0/3 | ND | ||

number of samples in which virus was detected from respiratory secretions out of total number of samples

ND = none detected

c N/A = not applicable as sample not collected

individual titer of virus from influenza-positive samples (log10 TCID50/ml)

The replication of the AA ca virus was restricted in NHPs. The virus was only detectable in 6/21 (29%) animals (Table 1), and was not detected in AGMs. The highest titer detected in the URT was 102.5 TCID50/g in the NT (Table 2), and 102.2 TCID50/ml in the NW (Table 3). The JAP57 ca Q-G virus was detected in a significantly greater number of NHPs than the AA ca virus: 13/21 (62%), compared to 6/21 (29%), p = 0.03 (Table 1). Altering the receptor-binding preference of JAP57 ca from α2-3 (Q-G) to both α2-3 and α2-6 linked sialic acid residues (L-S) resulted in an increased number of CMs and RMs with detectable virus in the URT from 3/6 (50%) to 4/6 (67%) and 5/6 (83%) respectively (Table 1); however, this did not reach statistical significance (p =0.29), and increased replication was not observed in AGMs. In addition, the highest titer to which the JAP57 ca L-S virus replicated in the URT (102.5 TCID50/g NT and 102.0 TCID50/ml NW) was similar to the JAP57 ca Q-G virus (105.0 TCID50/g NT and 102.7 TCID50/ml NW) (Tables 2 and 3). The TEC67 ca virus replicated in the highest percentage of NHPs [12/18 (67%)] compared to the other viruses, and virus was recovered from significantly more animals than the AA ca virus (p = 0.02) (Table 1).

4. Discussion

Influenza A viruses of the H2N2 subtype remain a pandemic threat, and vaccines are needed. To this end, we evaluated the H2N2 backbone of the licensed seasonal LAIV virus, AA ca. However, while it was immunogenic and replicated efficiently in mice and ferrets [13], it was poorly immunogenic and restricted in replication in humans [14]. After one dose, only 4/21 (19%) of subjects shed virus in NW samples, with a mean peak titer of 101.4 TCID50 /ml [14]. In the present study, we demonstrate that the replication of the AA ca virus in NHPs more closely reflects the data from the Phase I clinical trial than the data from mice or ferret studies, suggesting that NHPs may be more useful than mice or ferrets in evaluating the replication of candidate LAIV viruses prior to clinical trials. Moreover, because H2N2 LAIV viruses were recovered from a higher percentage of CMs and RMs than AGMs, CMs and RMs appear to be the most suitable species of NHP for studying H2N2 LAIV candidates. The TEC67 ca virus was detected in the highest percentage of animals compared to the other H2N2 LAIV viruses tested, and therefore may be the most promising candidate for further evaluation.

The data from this study are consistent with our previous evaluation of the replication of A/California/07/2009 pandemic H1N1 LAIV (CA09 ca) in different NHP species. The replication of the CA09 ca virus was restricted in NHPs, with only 5/24 (21%) of animals testing positive, with a peak titer of ~103 TCID50/g NT tissue. The virus was also detected in a higher percentage of RMs (4/12, 33%) than AGMs (1/12, 8%) [18], although viral replication in CMs was not evaluated.

In people, seasonal trivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine virus shedding varies between strains and inversely correlates with age, being most commonly detected in children under 5 years of age. In one study, 89% of children 6 months-2 years of age shed vaccine virus, compared to 69% of children between 2 and 5 years of age [28]. In another study, 44%, 27% and 17% of subjects aged 5-8, 9-17, and 18-49 years of age shed vaccine virus, respectively [29].

The basis for differential shedding of LAIVs in humans and NHPs is not clear. In people, previous exposure to influenza viruses may lead to antiviral immunity that limits the replication of seasonal LAIV viruses [30]. The subjects in the Phase I clinical trial were seronegative to H2 viruses [14], however responses directed at conserved epitopes could potentially limit viral replication. The NHPs used in our studies are influenza-naïve, so pre-existing immunity cannot explain our observations in this study, and additional host and virus factors may play a role in determining the efficiency of virus replication. The body temperature of NHPs is generally higher than humans, which may restrict replication of temperature sensitive LAIV to a greater extent. Anatomically, the URT is different in size and shape between different NHP species, and it is possible that other differences in the URT environment for example in mucus production, pH, or temperature may contribute to the observed differences in viral replication.

All of the viruses in this study shared the six internal protein genes from the AA ca virus and only differed in the HA and NA genes. It is therefore possible that differences in the receptor binding, pH of fusion, HA activation, or NA cleavage of sialic acid may contribute to the differences observed. However, we did not evaluate the replication of wild type H2N2 viruses in this study, so it is not possible to comment on whether their replication would be similarly restricted

The different NHP species used in this study were from different geographical origins: the RM were of Indian origin, the CM were of Indonesian origin and the AGMs were from St. Kitts. Therefore, there may be differences in host genetics that could influence virus replication. For example there could be differences in interferon induction, signaling, or interferon stimulated gene (ISG) expression between different species. The ISG MxA has been shown to restrict the replication of influenza viruses [31], and species-specific differences in the MxA gene can influence its antiviral activity [32]. Although the viruses tested in this study all shared their NP gene from the AA ca virus, it is possible that differences in the NHP MxA genes lead to differences in the innate antiviral responses that could in part explain the observed differences in virus replication. Consistent with this hypothesis, the MxA genes from CMs and RMs are more closely related to each other than to the MxA gene from AGMs [32], and the replication of AA ca, JAP57 ca Q-G and JA57 ca L-S viruses was more similar in CMs and RMs, than AGMs.

Species-specific differences in the distribution of influenza virus receptors in the respiratory tract could also lead to differences in the levels of viral replication. However, our understanding of the distribution of influenza virus receptors in the respiratory tract of different NHP species remains incomplete. We have previously shown that the AGM NT epithelium expresses α2-6 sialic acids, similar to humans [19]. It was therefore surprising that altering the receptor binding preference of the JAP57 ca virus from α2-3 to dual α2-3 and α2-6 sialic acid binding did not enhance viral replication. However, we have also found that avian influenza viruses of the H5, H6, and H7 subtypes replicate efficiently in the URT of AGMs, despite a receptor-binding preference for α2-3 linked sialic acids [19]. These data support the conclusions from recent glycan analyses that suggest categorizing receptors into α2-3 or α2-6 binding glycans is an oversimplification [33].

We have previously shown that LAIV viruses with modest replication in NHPs elicit serum antibody responses. The LAIV virus CA09 ca was only detected in 4/12 (33%) of RMs, yet all inoculated animals seroconverted and had a hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibody titer between 40 and 80, and a four-fold rise in geometric mean serum antibody titer after one dose of vaccine [18]. It is therefore likely that the viruses tested in the present study will elicit serum antibody responses in NHPs. However, it should be noted that a serum HAI antibody response has not been shown to be an absolute correlate of protection for LAIV. Although multiple clinical trials have shown that high rates of seroconversion following vaccination with LAIV were associated with high rates of vaccine efficacy, robust efficacy was also observed with low rates of seroconversion [34].

The level of LAIV virus replication necessary for a vaccine to be protective remains unknown. We have shown that in RMs, the LAIV virus CA09 ca was detected in 4/12 (33%) of animals and the CA9 wt challenge virus was detected in the lungs of 2/4 (50%) of animals after one dose of the vaccine [18]. In AGMs, the LAIV viruses A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) ca and A/chicken/Hong Kong/G9/97 (H9N2) ca were detected in 3/6 (50%) and 1/4 (25%) of animals, respectively. After one dose, homologous wt challenge virus was detected in the lungs of 3/3 (100%) and 2/4 (50%) animals, respectively [19]. In contrast, the LAIV viruses A/teal/Hong Kong/W312/97 (H6N1) ca and A/chicken/British Columbia/CN-6/2004 (H7N3) ca viruses replicated in 3/4 (75%) and 4/4 (100%) animals, respectively, and challenge virus was not detected in the lungs of any vaccinated animals after one dose of vaccine [19]. Taken together, these data indicate that replication of LAIV viruses in the majority of animals correlate with protection while LAIV viruses that replicate in a minority of animals confer only partial protection. Because the TEC67 ca virus replicated in the highest percentage of NHPs in the present study [12/18 (67%)], including 6/6 (100%) of CMs, it is reasonable to anticipate that this virus will elicit a more robust protective response than the other vaccine candidates.

Overall, our data indicate that NHPs are a useful model to evaluate the replication of LAIV candidate viruses and that CMs and RMs are the preferred species for studying H2N2 LAIV viruses. In addition, we suggest that the TEC67 ca virus merits further evaluation.

Highlights.

Non-human primates are more useful than mice or ferrets for evaluating LAIV virus replication.

Cynomolgus macaques are preferable for evaluating H2N2 LAIV candidate virus replication.

Influenza A/Tecumseh/3/67 (H2N2) ca is a promising LAIV candidate for further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). We would like to thank Dr. Richard Herbert, Joanne Swerczek, Mark Szarowicz and the staff of the NIH animal center at Poolesville for technical support in the animal studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Schonberger LB, Arden NH, Cox NJ, et al. Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:53–60. doi: 10.1086/515616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JC, Baranovich T, Marathe BM, Danner AF, Seiler JP, et al. Risk assessment of H2N2 influenza viruses from the avian reservoir. J Virol. 2014;88:1175–1188. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02526-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox NJ, Subbarao K. Global epidemiology of influenza: past and present. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:407–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabel GJ, Wei CJ, Ledgerwood JE. Vaccinate for the next H2N2 pandemic now. Nature. 2011;471:157–158. doi: 10.1038/471157a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonassen CM, Handeland K. Avian influenza virus screening in wild waterfowl in Norway, 2005. Avian Dis. 2007;51:425–428. doi: 10.1637/7555-033106R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishida N, Sakoda Y, Shiromoto M, Bai GR, Isoda N, et al. H2N5 influenza virus isolates from terns in Australia: genetic reassortants between those of the Eurasian and American lineages. Virus Genes. 2008;37:16–21. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0235-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krauss S, Obert CA, Franks J, Walker D, Jones K, et al. Influenza in migratory birds and evidence of limited intercontinental virus exchange. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e167. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma W, Vincent AL, Gramer MR, Brockwell CB, Lager KM, et al. Identification of H2N3 influenza A viruses from swine in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20949–20954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makarova NV, Kaverin NV, Krauss S, Senne D, Webster RG. Transmission of Eurasian avian H2 influenza virus to shorebirds in North America. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 12):3167–3171. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-12-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suss J, Schafer J, Sinnecker H, Webster RG. Influenza virus subtypes in aquatic birds of eastern Germany. Arch Virol. 1994;135:101–114. doi: 10.1007/BF01309768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafer JR, Kawaoka Y, Bean WJ, Suss J, Senne D, et al. Origin of the pandemic 1957 H2 influenza A virus and the persistence of its possible progenitors in the avian reservoir. Virology. 1993;194:781–788. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster RG. Predictions for future human influenza pandemics. J Infect Dis 176 Suppl. 1997;1:S14–19. doi: 10.1086/514168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. Safety, immunogencity, and efficacy of a cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60 (H2N2) vaccine in mice and ferrets. Virology. 2010;398:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talaat KR, Karron RA, Liang PH, McMahon BA, Luke CJ, et al. An open-label phase I trial of a live attenuated H2N2 influenza virus vaccine in healthy adults. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Yang CF, Jin H, Kemble G, et al. Evaluation of replication and cross-reactive antibody responses of H2 subtype influenza viruses in mice and ferrets. J Virol. 2010;84:7695–7702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00511-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, et al. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature. 2006;440:435–436. doi: 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Zhou H, Kim L, Jin H. The receptor binding specificity of the live attenuated influenza H2 and H6 vaccine viruses contributes to vaccine immunogenicity and protection in ferrets. J Virol. 2012;86:2780–2786. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06219-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boonnak K, Paskel M, Matsuoka Y, Vogel L, Subbarao K. Evaluation of replication, immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a live attenuated cold-adapted pandemic H1N1 influenza virus vaccine in non-human primates. Vaccine. 2012;30:5603–5610. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuoka Y, Suguitan A, Jr., Orandle M, Paskel M, Boonnak K, et al. African green monkeys recapitulate the clinical experience with replication of live attenuated pandemic influenza virus vaccine candidates. J Virol. 2014;88:8139–8152. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00425-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baskin CR, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Tumpey TM, Sabourin PJ, Long JP, et al. Early and sustained innate immune response defines pathology and death in nonhuman primates infected by highly pathogenic influenza virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3455–3460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herfst S, van den Brand JM, Schrauwen EJ, de Wit E, Munster VJ, et al. Pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza virus causes diffuse alveolar damage in cynomolgus macaques. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:1040–1047. doi: 10.1177/0300985810374836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh Y, Shinya K, Kiso M, Watanabe T, Sakoda Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature. 2009;460:1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature08260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, Kash JC, Copps J, et al. Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2007;445:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nature05495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, van Amerongen G, Bestebroer TM, Fouchier RA, et al. A primate model to study the pathogenesis of influenza A (H5N1) virus infection. Avian Dis. 2003;47:931–933. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086-47.s3.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safronetz D, Rockx B, Feldmann F, Belisle SE, Palermo RE, et al. Pandemic swine-origin H1N1 influenza A virus isolates show heterogeneous virulence in macaques. J Virol. 2011;85:1214–1223. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01848-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monto AS, Cavallaro JJ. The Tecumseh study of respiratory illness. II. Patterns of occurrence of infection with respiratory pathogens, 1965-1969. Am J Epidemiol. 1971;94:280–289. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed L, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. American Journal of Hygiene. 1938;27:494–497. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallory RM, Yi T, Ambrose CS. Shedding of Ann Arbor strain live attenuated influenza vaccine virus in children 6-59 months of age. Vaccine. 2011;29:4322–4327. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Block SL, Yogev R, Hayden FG, Ambrose CS, Zeng W, et al. Shedding and immunogenicity of live attenuated influenza vaccine virus in subjects 5-49 years of age. Vaccine. 2008;26:4940–4946. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Tobler S, Roayaei J, Eick A. Live attenuated or inactivated influenza vaccines and medical encounters for respiratory illnesses among US military personnel. JAMA. 2009;301:945–953. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimmermann P, Manz B, Haller O, Schwemmle M, Kochs G. The viral nucleoprotein determines Mx sensitivity of influenza A viruses. J Virol. 2011;85:8133–8140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00712-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell PS, Patzina C, Emerman M, Haller O, Malik HS, et al. Evolution-guided identification of antiviral specificity determinants in the broadly acting interferon-induced innate immunity factor MxA. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walther T, Karamanska R, Chan RW, Chan MC, Jia N, et al. Glycomic analysis of human respiratory tract tissues and correlation with influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003223. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandell A, Woo J, Coelingh K. Protective efficacy of live-attenuated influenza vaccine (multivalent, Ann Arbor strain): a literature review addressing interference. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10:1131–1141. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]