Abstract

Background

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) comprises a group of hereditary eye diseases characterized by progressive degeneration of retinal photoreceptors. It results in severe visual loss that may lead to legal blindness. Symptoms may become manifest during childhood or adulthood, and include poor night vision (nyctalopia) and constriction of peripheral vision (visual field loss). This field loss is progressive and usually does not reduce central vision until late in the disease course.The worldwide prevalence of RP is one in 4000, with 100,000 patients affected in the USA. At this time, there is no proven therapy for RP.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to synthesize the best available evidence regarding the effectiveness and safety of vitamin A and fish oils (docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)) in preventing the progression of RP.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) (2013, Issue 7), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to August 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to August 2013), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (January 1982 to August 2013), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 20 August 2013.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effectiveness of vitamin A, fish oils (DHA) or both, as a treatment for RP. We excluded cluster‐randomized trials and cross‐over trials.

Data collection and analysis

We pre‐specified the following outcomes: mean change from baseline visual field, mean change from baseline electroretinogram (ERG) amplitudes, and anatomic changes as measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT), at one year; as well as mean change in visual acuity at five‐year follow‐up. Two authors independently evaluated risk of bias for all included trials and extracted data from the publications. We also contacted study investigators for further information on trials with publications that did not report outcomes on all randomized patients.

Main results

We reviewed 394 titles and abstracts and nine ClinicalTrials.gov records and included three RCTs that met our eligibility criteria. The three trials included a total of 866 participants aged four to 55 years with RP of all forms of genetic predisposition. One trial evaluated the effect of vitamin A alone, one trial evaluated DHA alone, and a third trial evaluated DHA and vitamin A versus vitamin A alone. None of the RCTs had protocols available, so selective reporting bias was unclear for all. In addition, one trial did not specify the method for random sequence generation, so there was an unclear risk of bias. All three trials were graded as low risk of bias for all other domains. We did not perform meta‐analysis due to clinical heterogeneity of participants and interventions across the included trials.

The primary outcome, mean change of visual field from baseline at one year, was not reported in any of the studies. No toxicity or adverse events were reported in these three trials. No trial reported a statistically significant benefit of vitamin supplementation on the progression of visual field loss or visual acuity loss. Two of the three trials reported statistically significant differences in ERG amplitudes among some subgroups of participants, but these results have not been replicated or substantiated by findings in any of the other trials.

Authors' conclusions

Based on the results of three RCTs, there is no clear evidence for benefit of treatment with vitamin A and/or DHA for people with RP, in terms of the mean change in visual field and ERG amplitudes at one year and the mean change in visual acuity at five years follow‐up. In future RCTs, since some of the studies in this review included unplanned subgroup analysis that suggested differential effects based on previous vitamin A exposure, investigators should consider examining this issue. Future trials should take into account the changes observed in ERG amplitudes and other outcome measures from trials included in this review, in addition to previous cohort studies, when calculating sample sizes to assure adequate power to detect clinically and statistically meaningful difference between treatment arms.

Plain language summary

Use of vitamin A and fish oils for retinitis pigmentosa

Review question

We investigated how well vitamin A and fish oils work in delaying the progression of visual loss in people with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), and whether these treatments are safe.

Background

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the name given to a group of inherited eye disorders that cause a gradual, yet progressive, loss of vision. People with RP have difficulty seeing in low light conditions, problems with peripheral vision (potentially leading to 'tunnel vision'), and, in most cases, gradually become visually‐impaired. RP is diagnosed by visual field testing, which detects problems in peripheral vision, and by electroretinography, which determines the progression of RP by measuring the eye's responses to flashes of light through electrodes on the eye.

Study characteristics

We identified three clinical studies conducted in the USA and Canada. These studies included 866 participants with RP aged between four and 55 years, who were followed for an average of four years after administration of treatment. One study compared a fish oil extract (docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 400 mg per day)), to placebo (pretend medicine); the second study compared vitamin A (15000 IU per day) to vitamin E (400 IU per day) and to very low levels of vitamins (vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace); and the third study compared DHA (1200 mg per day) + vitamin A (15000 IU per day) to vitamin A alone (15000 IU per day). The evidence is current to August 2013.

Key results

All these studies measured the following outcomes: worsening in visual field, worsening in visual acuity (sharpness), and worsening in electroretinography results. Generally, comparison of participants who received vitamin A with or without fish oils (DHA) with participants who received placebo, did not show any difference for these outcomes, which means that the use of high‐dose vitamin A or fish oils does not significantly slow progressive visual loss in people with RP. None of the studies reported any systemic adverse events from vitamin A or fish oil. However, the long‐term adverse effects of high‐dose vitamin A and fish oil are not known.

Quality of evidence

The trials appear to have been well designed and well conducted, so we determined the quality was good for all included studies.

Background

Description of the condition

The term retinitis pigmentosa (RP) comprises a diverse group of diseases characterized by progressive degeneration of the retinal photoreceptors (light‐sensing cells) and the adjacent retinal pigment epithelium. RP may occur as part of a syndrome, including abnormalities of other organs, or in a non‐syndromic form in which the clinical manifestations are restricted to the eye (65% of all cases in the USA) (Daiger 2007). RP is often associated with other ocular abnormalities in addition to retinal degeneration, such as cataract (clouding of the lens of the eye) or cystoid macular edema (swelling of the central retina). The worldwide prevalence of RP is one in 4000, with 100,000 people affected in the USA (Hartong 2006).

RP is a genetic condition and its inheritance pattern may be autosomal dominant (30%), autosomal recessive (20%), X‐linked (15%), mitochondrial (5%), or sporadic (30%). At least 50 separate gene defects have been reported to be associated with RP (Daiger 2007).

Depending on the specific genetic variant, symptoms may become manifest during childhood or adulthood. The initial symptoms are typically poor night vision (nyctalopia) and constriction of peripheral vision (visual field loss). This field loss is progressive and usually central vision is not reduced until late in the disease course.

The natural course of RP involves an approximate 4% to 12% annual loss of visual field (Berson 1985). In addition to the visual field loss, deterioration of visual acuity and full‐field electroretinogram (ERG) changes are observed. Visual acuity loss occurs more gradually compared to visual field loss and is more severe if the central retina (the macula) is affected (Flynn 2001; Holopigian 1996). On average, a decline in visual acuity of one line is observed over five years for patients without macular lesions, compared to a loss of three to four lines in patients with macular involvement (Flynn 2001).

The diagnosis of RP is made on clinical examination. Typical findings include abnormal pigmented changes in the peripheral retina (known as bone spicules, because of their similarity to the microscopic appearance of bone), pallor (paleness) of the optic disc (or optic nerve head, part of the optic nerve) and attenuation (narrowing) of the retinal blood vessels. Cataract and cystoid macular edema also may be noted.

Peripheral vision is measured with visual field testing, frequently with a static Humphrey perimeter (automated threshold perimeter) or kinetic Goldmann perimeter. Full‐field ERG provides additional quantitative measurement of disease progression. RP patients have reduced rod (elicited by dark‐adapted flash) and cone (elicited by single flash) response amplitudes and a delay in timing from stimulus to peak rod‐ or cone‐isolated responses (Berson 1969). It has been estimated that RP patients lose approximately 17% of remaining ERG amplitude per year (Berson 1985). Changes in the ERG are generally observed before clinical detection of changes in visual field and visual acuity.

Recent studies have documented microscopic changes in the retinal layers using a newer, noninvasive clinical test called optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Walia 2007; Witkin 2006). Witkin 2006 reported that the foveal photoreceptor outer segment/pigment epithelial thickness was significantly lower in eyes with RP than in controls. Oishi 2009 correlated findings from OCT with changes in visual acuity: patients without integrity of the inner segment‐outer segment junction of the photoreceptors had greater loss of visual acuity than patients with a more normal tomographic appearance.

Description of the intervention

Certain ophthalmic diseases associated with RP may be treated successfully. For example, cataract surgery may be performed for RP‐associated cataract and various medications may be effective in the treatment of RP‐associated cystoid macular edema. However, there is no proven treatment that slows or delays the progressive retinal degeneration.

Treatments that have been studied include oral supplementation with vitamin A (retinyl palmitate), the omega‐3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), or both (Birch 2005; Hodge 2005).

How the intervention might work

Mechanisms through which vitamin A and DHA might modify the disease process in RP have not yet been fully explained. However, vitamin A has been reported to have an important role in the function of retinal photoreceptors (Berson 1982; Dowling 1960). Rhodopsin is a pigment located in retinal rods that allows the rods to detect small amounts of light. Rhodopsin, along with other pigments in the retina, stores vitamin A compounds; vitamin A is important for rhodopsin formation and the visual cycle.

DHA, similarly, is found within photoreceptor cell membranes, and some authors have suggested that it has a functional role (Chen 1996).

Why it is important to do this review

RP is an uncommon, but clinically important disease. It is progressive, potentially blinding, and has no proven treatment. Vitamin A and fish oils have been proposed as having some therapeutic potential in some of the clinical trials conducted. Therefore, synthesis of all available evidence on this topic in a systematic review is warranted.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to synthesize the best available evidence regarding the effectiveness and safety of vitamin A and fish oils (docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)) in preventing the progression of RP.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of any design, including parallel and factorial, in this review. We did not include cross‐over trials or cluster‐randomized trials, as these designs could not address our question of interest.

We excluded studies that used quasi‐random allocation methods such as alternation, case‐record numbers, dates of birth or days of the week for randomizing participants to a group. Although trials with quasi‐random allocation methods may provide data that support findings from RCTs, they are susceptible to selection bias and confounding.

Types of participants

We included trials that enrolled participants of any age diagnosed with any degree of severity or type of RP. If trials included participants with varying severity or stage of disease, we extracted baseline characteristics to explore disease severity as a source of variability across trials (see 'Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity' section).

Types of interventions

We included trials evaluating the effectiveness of vitamin A (administered as vitamin A1, retinyl palmitate, 11‐cis retinol, retinol, tretinoin or all‐trans‐retinol), fish oils (administered as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), omega‐3 fatty acids or eicosapentaenoic acid, fish‐liver oils and cod‐liver oil) or both, for any duration, as a treatment for RP.

We included trials when the following interventions and comparisons were used in studies:

1. For participants received the following interventions:

only fish oils or only vitamin A;

fish oils along with any (one or more than one) type of other vitamin(s);

vitamin A along with any (one or more than one) type of vitamin(s); or

We included trials in which participants receiving the above‐mentioned interventions were compared to participants receiving placebo, vitamins (other than vitamin A) or no therapy.

2. For participants received the following interventions:

both fish oils and vitamin A;

both vitamin A and fish oils in combination with other vitamins.

We included trials in which participants receiving the above‐mentioned interventions were compared to participants receiving placebo, vitamins (including vitamin A) or no therapy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mean change in visual field sensitivity (measured in decibels ‐ dB) at one year follow‐up. We also pre‐specified that we would analyze this outcome at other follow‐up times using available data (i.e. two, three, four and five years). If the investigators could not provide mean change values, we planned to report the proportion of participants with visual field loss for these trials.

Visual field may be measured using different instruments such as the Humphrey field analyzer and Goldmann perimeter. We described the methods used to measure visual field (by instrument, manual versus automated, threshold versus kinetic perimetry) and programs used to analyze automated threshold perimetry (e.g. 30‐2, 30/60‐1) in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Secondary outcomes

Visual acuity: in the protocol for this systematic review, we specified the change in logMAR visual acuity at five year follow‐up. We examined data at other times of follow‐up (one, two, three and four years of follow‐up) as well, because these were reported in the included trials.

Electroretinography (ERG): we analyzed the log mean change in ERG amplitude (rod response, mixed response and cone response) at one year. We also examined this outcome at other times of follow‐up (two, three, four and five years). When ERG findings were reported in other ways, we summarized available data.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT): analysis of this variable included the change from baseline in tomographic features, especially the junction between the photoreceptor outer segments and inner segments, at one year and at other times of follow‐up as available.

Adverse effects (severe, minor)

We summarized any adverse outcomes reported in the included trials. Specific adverse events of interest were systemic complications such as liver injury, elevated blood lipid levels, increased intracranial pressure, bone changes, teratogenicity (association with birth defects), and ocular complications such as loss of six or more lines of visual acuity at one‐year follow‐up.

Quality of life measures

We reported any quality of life measures associated with patient satisfaction, subjective visual improvement and any other vision‐related quality of life measures assessed by questionnaires or other methods that were reported in the trials.

Follow‐up

We included trials with follow‐up of one year or longer in the review. We planned to conduct meta‐analysis, where possible, for trials with similar lengths of follow‐up.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) 2013, Issue 7, part of The Cochrane Library. www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 20 August 2013), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to August 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to August 2013), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (January 1982 to August 2013), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (www.controlled‐trials.com), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 20 August 2013.

See: Appendices for details of search strategies for CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3), LILACS (Appendix 4), mRCT (Appendix 5), ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 6) and the ICTRP (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of the publications from studies eligible for inclusion in the review for information about other possible trials. We used the Web of Science database to identify additional studies that cited the included trials. Electronically, we also searched abstracts from the annual meetings of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) and the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO).

We did not contact individuals or organizations to identify trials for this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SR, SGS), working independently, assessed the titles and abstracts resulting from the searches. Each author classified the citations as 'definitely include', 'possibly include (unsure)' and 'definitely exclude'. We obtained the full text publications of listings classified as definitely include and possibly include (unsure) to see whether they were from studies that met the inclusion criteria, and then reclassified them as 'include', 'exclude' or 'awaiting classification'. We scanned the reference list of included studies manually to identify additional relevant citations. For studies classified as 'awaiting classification' by both authors, we requested additional information from study investigators for clarification.

We did not mask review authors to any trial details in this process. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. We tabulated excluded trials along with reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SR, SGS), working independently, extracted data from the publications of all included studies using data extraction forms developed by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group and pilot tested specifically for this review. The authors resolved any discrepancies through discussion.

Information extracted for each study included the following.

Methods: method of randomization, allocation concealment, masking (blinding), number randomized to each trial arm, exclusions after randomization, losses to follow‐up and unusual study design features.

Participants: country where participants were enrolled, age, sex and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Interventions: details of test intervention and comparison intervention (control) including dose and frequency of administration and duration of intervention.

Outcomes: visual field (primary outcome), visual acuity (secondary outcome), ERG measurements (secondary outcome), adverse events, any other outcomes assessed and percentage of participants for whom no outcome data were reported.

Follow‐up and analysis: length of follow‐up, reasons stated for dropouts or withdrawal, compliance and methods for analysis.

Others: additional details (such as funding sources) and publication year.

When any of the above data were missing from publications of a trial, we attempted to contact the study investigators for further information. If we did not receive a response within two months (after three emailed messages and one telephone contact), we proceeded without the missing information.

One author (SR) entered data into the Review Manager software (RevMan 2012), and the second author (SGS) verified the data entered against data extracted from the publications.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SR, SGS) independently assessed the risk of bias according to the following criteria described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We assessed the six criteria below individually for risk of bias, grading each as low, high or unclear (indicating either uncertainty or a lack of information). We provided a description for each judgment of bias.

Adequate sequence generation (selection bias): we categorized a study as being at low risk if the sequence was generated using a computer program or a random‐numbers table. We categorized all other methods as high risk or unclear (risk).

Allocation concealment (selection bias): we categorized a study as being at low risk if the participants or the investigators enrolling the participants could not determine the assignments (e.g. use of central allocation, sequentially‐numbered or opaque sealed envelopes). We categorized all other methods as being at high risk or unclear.

Masking of participants: we assessed whether the methods used to mask participants were adequate and categorized a study for risk of bias accordingly. When adequate methods to mask knowledge of the assigned intervention were used and described, such as similar‐looking pills administered at similar times of the day, we categorized a study as being at low risk of bias. We categorized all other methods as being at high risk or unclear.

Masking of care providers: we assessed whether the methods used to mask physicians and other care providers were adequate and categorized a study for risk of bias accordingly. When adequate methods to mask knowledge of the assigned intervention were used and described in specific language indicating masking, we categorized a study as being at low risk of bias. We categorized all other methods as being at high risk or unclear.

Masking of outcome assessors: we assessed whether the methods used to mask outcome assessors with regard to the treatment arm were adequate and categorized a study for risk of bias accordingly. When adequate methods to mask knowledge of the assigned intervention were used and described, such as analyzing each assessment (such as visual field) without access to prior tests, we categorized a study as being at low risk of bias. We categorized all other methods as being at high risk or unclear.

Incomplete outcome data: we assessed included trials for exclusions after randomization and losses to follow‐up along with their reasons to determine the risk of bias. We categorized a study as being at low risk of bias when there were no missing outcome data or the reasons for missing outcome data were not related to the true outcome, the reasons for missing data were similar across the groups or when the missing data had been imputed using appropriate methods. We categorized all other reasons as being at high risk or unclear.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to use risk ratios (i.e. relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI)) as the measure of effect for dichotomous outcomes (proportion of patients with new visual field defects, visual acuity data reported as dichotomous outcomes and proportion of patients with adverse events). We calculated a mean difference for continuous outcomes (mean change in visual field, logMAR visual acuity, and mean change in ERG amplitude).

A priori, we decided that wherever visual acuity data were reported as a dichotomous outcome, we would attempt to contact the investigators for mean change values. If no additional data were available from the investigators, we would analyze visual acuity as a dichotomous outcome (such as proportion of participants losing two or more lines of visual acuity) using data in the trial report.

We planned to summarize the electroretinogram either as a continuous outcome or a dichotomous outcome based on available data. We analyzed the mean change in ERG amplitude as a continuous outcome. We planned to analyze the proportion of participants with non‐detectable ERG patterns in response to high frequency flickers (30 or 31 Hz) as a dichotomous outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

Since participants in the included trials were given systemic treatment, the unit of analysis was the individual. When data were available for both eyes of an individual, we planned analysis for the average of the two eyes for continuous outcomes. For vision‐related dichotomous outcomes (e.g. visual acuity), we will use the eye as the unit of analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the investigators for further information on trials with publications that did not report outcomes on all randomized participants. We planned that if they did not respond after three emailed messages and telephone contacts, initiated within two months, we would assess the study on the basis of the available information. One author responded, but was unable to provide any additional data or information that was missing from the publication. We attempted to extract data on standard deviations for the change from baseline if a P value or a CI was reported, using methods described in Chapter 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). We did not attempt to impute the standard deviations using possible values of correlation coefficients. Analyses were conducted by the intention‐to‐treat principle, with all participants analyzed in the group to which they were randomized, to the extent permitted by the methods described here. If the data in the publication or the trial investigators were unable to provide data to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis, we conducted analysis on the available number of participants in the publication.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by examining the characteristics of the included studies and by visual examination of the forest plots; we used the I2 statistic and Chi2 test to assess statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We would have used a funnel plot to identify evidence of publication bias, if there had been a sufficient number of included trials. We did not have access to the trial protocols to assess selective outcome reporting.

Data synthesis

We pre‐specified in the protocol for this review that if we found substantial heterogeneity across studies, either because of clinical heterogeneity (variability in types of participants, interventions, follow‐up etc.) or statistical heterogeneity (I2 values greater than 50%, statistically significant Chi2 test for heterogeneity), we would not attempt a meta‐analysis but would present an estimate of effect and associated 95% confidence interval for each individual trial. If there was little variation between trials, we planned to conduct a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis if we had two or three trials and there was no clinical heterogeneity and minimal statistical heterogeneity (as indicated by I2 values), and to conduct a random‐effects meta‐analysis when there was no clinical heterogeneity but there was moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 values of 30% to 50%).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we had found substantial heterogeneity, we planned to explore the reasons for this heterogeneity by examining details from the trials including types of participants (baseline characteristics including severity of the disease, genetic profile and syndromic or non‐syndromic RP), interventions (frequency and dose), duration of follow‐up, methodological characteristics such as losses to follow‐up, reasons for losses to follow‐up and outcome measurement methods. We provided a qualitative analysis and summary of the variability across included trials. If the included trials provided sufficient data, we planned to conduct a subgroup analysis based on whether patients have syndromic or non‐syndromic RP.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of excluding studies with poor methodological quality (high risk of bias for all or a large majority of items) and industry‐funded studies.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; and Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

We retrieved a total of 394 titles and abstracts and nine ClinicalTrials.gov records from the electronic searches. After removing 70 duplicate records, we reviewed 324 titles and abstracts and nine ClinicalTrials.gov records for eligibility, and excluded 322 of these records. Both review authors (SR and SGS) selected 11 records relating to 10 studies as being potentially relevant, and reviewed full text of these records. We excluded seven records relating to seven studies: four were uncontrolled trials and three were not related to our predefined outcome of interest. Of the four remaining records, one was a subgroup analysis of an already included trial, reported in a different publication. The flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Results from searching for studies for inclusion in the review

We did not identify any additional trials through searching the reference lists of the included studies or the Web of Science database. Altogether, we included three trials in this review (Berson 1993; Berson 2004a; Hoffman 2004).

Included studies

For each included study, we presented detailed characteristics of the trial in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table and Table 1. Table 1 summarizes the study design, baseline characteristics of the participants and interventions across the included trials.

1. Summary of included trials.

| Study ID | Berson 1993 | Berson 2004 | Hoffman 2004 |

| Design | 2x2 factorial design | Parallel | Parallel |

| Genetic profile of participants | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal dominant | Not included |

| Autosomal recessive | Autosomal recessive | Not included | |

| X‐linked | X‐linked | X‐linked | |

| Dominant with mutation | Dominant with mutation | Not included | |

| Isolate | Isolate | Not included | |

| Undetermined | Undetermined | Not included | |

| Age range | 18‐49 years | 18‐55 years | 4‐38 years |

| Gender (% female) | Men and women (38%) | Men and women (49%) | Only males (0%) |

| Number randomized | 601 | 221 | 44 |

| Intervention(s) | Vitamin A + vitamin E

trace = 146 Vitamin A + vitamin E = 151 Vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace =149 Vitamin A trace + vitamin E = 155 |

DHA + vitamin A = 105 (number analyzed) DHA placebo + vitamin A = 103 (number analyzed) |

DHA = 23 DHA placebo = 21 |

| Dose | Vitamin A = 15000 IU/d Vitamin A trace = 75 IU/d Vitamin E = 400 IU/d Vitamin E trace = 3 IU/d |

DHA, 1200 mg/d Vitamin A, 1500 IU/d |

DHA, 400mg/d |

| Primary outcome | Cone ERG amplitude | Visual field (total point score for 30‐2 HFA) | Cone ERG amplitude |

| Other outcomes | Rod ERG, visual acuity, visual field | Cone ERG, visual acuity, visual field (total point score for 30‐2 and 30/60‐1 programs combined) | Rod ERG, visual acuity, visual field, dark adaptation |

| Length of follow‐up | 4‐6 years | 4 years | 4 years |

DHA: docosahexaenoic acid

ERG: electroretinogram

Study design and setting

All three trials included in our review were conducted in the USA, although Berson 1993 also included participants from Canada. Two were RCTs with parallel group design and one employed a factorial design (Berson 1993). Participants were primarily recruited from eye registries and clinical centers supported by the Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB). Hoffman 2004 recruited patients from the Southwest Eye Registry and from the clinical centers supported by FFB while Berson 1993 and Berson 2004a recruited patients from the Baltimore Eye Registry, from the centers supported by FFB, and from the contacts of private ophthalmologists.

Types of participants

A total of 866 patients were enrolled, and 853 were analyzed in the included studies for this review. The trials varied in size from 44 participants (Hoffman 2004), to 601 participants (Berson 1993). The age of participants in the included trials ranged from four to 55 years. Hoffman 2004 included children and a younger range of participants (4 to 38 years) than the other two trials. Both male and female participants were included in two trials, but one trial enrolled only male participants (Hoffman 2004). In all three trials, RP was diagnosed in all participants by an ophthalmologist.

People with atypical forms of retinitis pigmentosa (such as unilateral RP, sector RP, paravenous RP) and most syndromic forms of RP (Bardet‐Biedl syndrome, Bassen‐Kornzweig syndrome, Refsum disease, Usher's syndrome type 1) were not included in any of the three trials. However, people with some syndromic forms of RP (including Usher's syndrome type 2 (RP associated with partial hearing loss)) were included in two trials (Berson 1993; Berson 2004a). Participants with all levels of genetic predisposition were included in these trials (autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X‐linked, dominant with mutation, isolate and undetermined) except for Hoffman 2004, which included only patients with X‐linked RP.

Different instruments were used to measure visual field in the trials included in this review, resulting in different measures of baseline values. Kinetic perimetry was used in Berson 1993, whereas static perimetry was used in Hoffman 2004 and Berson 2004a. Guidelines for converting results between kinetic and static perimeters have been reported by Anderson and colleagues (Anderson 1989). Participants enrolled in Berson 2004a had a baseline HFA 30‐2 program total point score > 250 dB, using size V test light, whereas those enrolled in Berson 1993 had a central visual field diameter of ≥ 8 degrees (Goldman V‐4‐e). A baseline visual field result was not specified in Hoffman 2004.

Visual acuity was measured using Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) charts in all three trials. Participants enrolled in Berson 1993 and Berson 2004a were required to have a baseline minimum visual acuity of 20/100 (Snellen equivalent), but a baseline visual acuity minimum was not specified in Hoffman 2004.

Participants with > 0.68 µV of cone ERG were included in two trials (Berson 2004a; Hoffman 2004), and participants with cone ERG of at least 12 µV were included in the third (Berson 1993). The percentages of participants with a measurable rod response at baseline were 61% (366/601), 55% (114/208), and 50% (22/44) in Berson 1993, Berson 2004a, and Hoffman 2004, respectively. In all three trials, response amplitude to cone ERG of < 2 µV were narrowband amplified in order to reliably distinguish responses > 0.05 µV from noise.

We identified clinical heterogeneity among participants in the three trials on several aspects including age of the participants, genetic predisposition, gender, and baseline severity. Participants in Hoffman 2004 were younger than those in Berson 1993 and Berson 2004a; the mean age was 16 ± 9 years versus 32.5 ± 0.7 years versus 37.8 ± 0.90 years. The baseline severity of RP varied among the trials as described above for baseline values of ERG, visual field and visual acuity. We were unable to extract data on the outcomes specified in the protocol for this review based on the genetic profile of participants.

Types of interventions

Trials included in this review evaluated different interventions. Docosahexanoic acid (DHA) only was administered in Hoffman 2004. Vitamin A (along with vitamin E for some patients) was administered in Berson 1993. Both DHA and vitamin A was administered in Berson 2004a. The doses also varied between trials. Hoffman 2004 administered 400 mg of DHA per day whereas Berson 2004a administered 1200 mg of DHA per day. Vitamin A was administered at a dose of 15000 IU for both trials in which it was used (Berson 1993; Berson 2004a). Interventions (vitamin A and DHA) were administered orally in the form of gelatin capsules for a minimum period of four years. However in Berson 1993, 43% of patients received the test or control intervention for six years.

Comparison intervention: DHA was compared to placebo in Hoffman 2004, DHA + vitamin A was compared to vitamin A alone in Berson 2004a, and vitamin A was compared to trace vitamins group (vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace) in Berson 1993.

Excellent compliance was documented in Berson 1993, (94% of capsules were consumed in any given year by 88% of participants), and Berson 2004a (92% of DHA capsules and 94% of vitamin A capsules were consumed over all four years). Hoffman 2004 reported poor compliance in five of 44 patients (11.4%), using analysis of red blood cell levels of DHA.

Types of outcomes

Our primary outcome measure, visual field sensitivity, was analyzed as a secondary outcome measure in Hoffman 2004 and Berson 1993, and was a primary outcome measure in Berson 2004a. The primary outcome in the remaining two included trials was full field cone ERG amplitude (Berson 1993; Hoffman 2004), which was measured annually. Table 2 shows how each of the visual outcomes in the included trials was analyzed.

2. Summary of analysis of visual outcomes (visual field and visual acuity) in included trials.

| Outcome | Berson 1993 | Berson 2004 | Hoffman 2004 | |

| Visual field | Instrument used | Goldmann perimeter (V‐4‐e white test light) | Humphrey field analyzer 30‐2 program | 640 Humphrey field analyzer, Program 30‐2 |

| Effect measure | Percent decline per year of remaining visual field area | Mean annual rate loss of field sensitivity | Mean change in defect in Humphrey spot size III field from baseline at 4 years | |

| Method used for estimation | Longitudinal regression analysis | Longitudinal regression analysis | Mean change from baseline | |

| Estimate | Vitamin A + vitamin E

trace = 5.6% Vitamin A + vitamin E = 6.2% Vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace = 5.9% Vitamin A trace + vitamin E = 6.3% |

DHA + vitamin A = 36.95 ± 3.36

dB/year Control + vitamin A = 37.68 ± 3.36 dB/year |

DHA = 2.4 ± 3.66 dB (0.24 logMAR) Placebo = 1.4 ± 1.32 dB (0.14 logMAR) | |

| Data interpretation | No significant vitamin A or vitamin E main effects or interaction effects were observed |

No significant difference | No significant difference | |

| Visual acuity | Instrument used | EDTRS chart | EDTRS chart | EDTRS chart |

| Effect measure | Number of EDTRS letters lost per year |

Annual rate of decline of EDTRS visual acuity over 4 years | Mean group difference in log MAR visual acuity between years 0 and 4 for the average of both eyes | |

| Method used for estimation | Longitudinal regression analysis | Longitudinal regression analysis | Mean change from log MAR baseline visual acuity | |

| Estimate | Vitamin A + vitamin E

trace = 1.1 letters/year Vitamin A + vitamin E = 0.7 letters/year Vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace = 0.9 letters/year Vitamin A trace + vitamin E = 0.9 letters/year |

DHA + vitamin A = 0.71 + 0.12

letters/year Control + vitamin A = 0.68 + 0.12 letters/year |

DHA = 0.05 ± 0.23 log

units (logMAR) Placebo = 0.06 ± 0.2 log units (logMAR) |

|

| Data interpretation | No significant difference | No significant difference | No significant difference |

DHA: docosahexaenoic acid

EDTRS: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

RCT: randomized controlled trial

Excluded studies

Of the eleven articles with a full text review, we excluded seven studies (Bergsma 1977; Berson 2010; Dagnelie 2000; Fex 1996; Sibulesky 1999; Tcherkes 1950; Wheaton 2003). We present the reasons for their exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

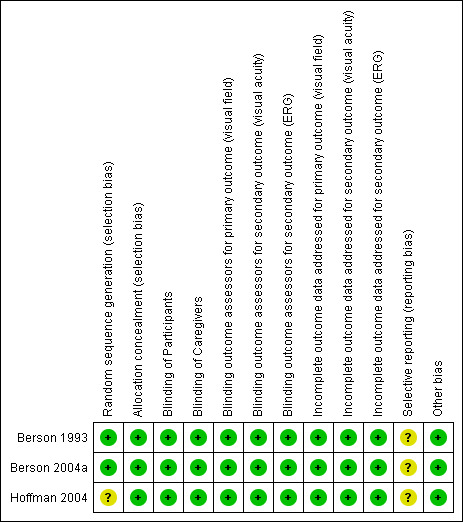

We evaluated the risk of bias for all included trials using the six prespecified domains described in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section. Blinding of outcome assessors and incomplete outcome data reporting were categorized into three criteria each by primary and secondary outcomes, so we recorded a total of 12 criteria in the tables marked 'Characteristics of included studies' and Figure 2. We found Berson 1993, Hoffman 2004, and Berson 2004a to have a low overall risk of bias. Summary of risk of bias assessment is shown in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias domain for each included study

Allocation

The random sequence was generated adequately in Berson 1993 and Berson 2004a using computer‐generated random numbers. Hoffman 2004 used a cluster RCT strategy, as relatives were randomized together to the same intervention to eliminate a potential for mixing of capsules. In the Methods section, we have stated that we intend to exclude cluster‐randomized trials, and although Hoffman 2004 mentioned that the relatives were randomized to same intervention using cluster RCT strategy, the strategy was not clearly and adequately described, and it was not clear how many relatives were randomized or what percent of randomized individuals were randomized using cluster RCT strategy. In addition, upon our assessment, we found that individuals were randomized to treatment groups. Therefore, we don't consider Hoffman 2004 a cluster‐randomized trial, so we decided to include it.

Allocation was implemented using a centralized system in Berson 1993 and Berson 2004a, which implies that personnel enrolling participants could not determine the next assignment. In Hoffman 2004, it was unclear whether there was adequate allocation concealment.

Blinding

All three included trials masked all personnel (participants, investigator, caregiver, outcome assessors) adequately. The outcome assessors were masked to both primary (visual field) and secondary (visual acuity and ERG) outcomes. OCT was not performed in any of the included trials.

Incomplete outcome data

In Hoffman 2004, 44/44 patients completed three years of follow‐up and 41/44 patients completed four years of follow‐up. Three people had missed visits over the entire span of study. The trialists imputed data for missed visits using the last observation carried forward method and performed intention to treat analysis. In Berson 2004a and Berson 1993, the trialists imputed missed measurements using multiple imputation methods. We assessed all trials as having accounted for incomplete outcome data adequately.

Selective reporting

We did not have access to protocols or to other information that would have allowed us to assess selective reporting in the included trials.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not assess the potential for publication bias using a funnel plot or other means, given that we identified only three trials that were eligible for inclusion.

Effects of interventions

All trials included in the review reported visual field, visual acuity and ERG as either a primary outcome or secondary outcome. None of the trials reported OCT as an outcome.

We elected not to conduct a meta‐analysis because of clinical heterogeneity in the types of participants included and differences in the intervention and comparison groups studied (as described in earlier sections of this review) across the included trials. In addition, we were unable to extract data from included trials on outcomes pre‐specified in the protocol for this review. Although the outcomes measured in all three trials included visual field, ERG amplitude, and visual acuity, they were analyzed and reported in ways that did not allow quantitative synthesis and comparison of data. Thus, we are unable to report a summary effect of interventions in terms of outcomes pre‐specified in the protocol. We have not, as yet, received a response from authors to email requests for data on the outcomes specified in the protocol for this review in a format that would allow us to perform quantitative synthesis.

Table 2 and Table 3 illustrate the variability across included trials in defining the outcome variable and its analysis for visual field, visual acuity and ERG amplitude.

3. Summary of analysis of electroretinogram (ERG) in included studies.

| Berson 1993 | Berson 2004 | Hoffman 2004 | ||||

|

Effect

measure and estimate |

Rate of decline of remaining 30 Hz ERG amplitude per year | Vitamin A + vitamin E trace = 6.1% Vitamin A + vitamin E = 6.3% Vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace = 7.1% Vitamin A trace + Vitamin E = 7.9% |

Annual rate of decline of 30 Hz ERG amplitude, loge % decline | DHA + vitamin A = 0.10 ± 0.01 Control + vitamin A = 0.11 ± 0.01 |

The mean (±1 SD) change in log cone ERG amplitude by 4th year | DHA = ‐0.199 ± 0.172 log μV Placebo = ‐0.266 ± 0.173 log μV |

| Percentage of participants with less than 50% decline in 30 Hz ERG amplitude relative to baseline at year 6 (high amplitude cohort); | Vitamin A + vitamin E trace = 62% Vitamin A + vitamin E=50% Vitamin A trace + Vitamin E trace = 48% Vitamin A trace + Vitamin E = 27% |

Mean annual rate of decline of remaining 30 Hz ERG function | DHA + vitamin A = 9.92% Control + vitamin A = 10.49% |

Mean change from baseline after 4 years in log cone ERG amplitude (text) and for all years of follow‐up | "A repeated‐measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of year(<.0001), with the population as a whole showing significant progression. The main effect of group was not significant (P=.16), and the interaction between group and year was not significant (P=.61)." | |

| Mean change from baseline for each year of follow‐up (for high‐amplitude cohort) | Data in figure only | |||||

| Method used for estimation | Longitudinal regression analysis Survival analysis Mean change analysis |

Longitudinal regression analysis | Subtracting the mean baseline log amplitude from the mean follow‐up log amplitude | |||

| Data interpretation | The vitamin A group had, on average, a slower rate of decline of retinal function than the 2 groups not receiving this dosage | No significant difference | No significant difference | |||

DHA: docosahexaenoic acid ERG: electroretinogram SD: standard deviation

A narrative summary of evidence reported is presented below using analyses described in the included trials. This description may be revised in an update of this review using data provided by trial authors in response to our request on the outcomes specified in the review protocol.

Visual field

Two trials examined the treatment effect associated with DHA (Berson 2004a; Hoffman 2004), and one trial examined the effect of vitamin A on visual field (Berson 1993), although they reported different measurement parameters. In all studies measuring visual field either as a primary outcome (Berson 2004a), or secondary outcome (Berson 1993; Hoffman 2004), there was no evidence of difference in rates of loss of visual field over four years between the treatment and control groups.

The primary outcome measure reported in Berson 2004a was the measurement of static perimetric sensitivities (total point score, i.e. overall assessment) on the HFA 30‐2 program with size V target. There were no statistically significant differences in the mean annual rates of decline between the intervention group (participants receiving DHA and vitamin A, 36.95 ± 3.36 dB per year) and the control group (participants receiving placebo and vitamin A, 37.68 ± 3.36 dB per year, P value 0.88). The investigators reported the combined total point score on the HFA 30‐2 and 30/60‐1 programs as a secondary outcome measure. Again, there were no statistically significant differences in the mean annual rates of decline between the intervention group (57.21 ± 4.90 dB per year) and the control group (59.59 ± 4.90 dB per year, P value 0.73). However, in a separate publication (Berson 2004b), the investigators reported a post hoc subgroup analysis (in a group of participants taking vitamin A prior to entry into the trial compared to those not taking vitamin A prior to entry into the trial). They concluded that among participants not taking vitamin A prior to entry in the trial, the mean annual rates of decline of central and total field sensitivity were statistically significantly lower in the intervention group (DHA + vitamin A) than in the control group (placebo + vitamin A) in the first and second years of follow‐up, but not in third and fourth years of follow‐up.

In contrast, Hoffman 2004 reported the focal assessment of change, presented in mean field defect (average of all differences from mean normal) using the HFA 30‐2 program with size III target and the 30/60‐2 program for patients with sufficient peripheral function. There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention group (DHA, 2.4 ± 3.66 dB over four years) and the control group (placebo, 1.4 ± 1.32 dB over four years, P value 0.29).

In Berson 1993, the percentage decline in the residual visual field (on kinetic Goldman perimetry) was 5.6% in the intervention group (vitamin A + vitamin E trace) and 5.9% in the control group (vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace), with no significant difference between the groups.

Visual acuity

Visual acuity was assessed as a secondary outcome in all trials included in this review. Two trials examined the effect of DHA on visual acuity (Berson 2004a; Hoffman 2004), and one trial examined the effect of vitamin A on visual acuity (Berson 1993). Visual acuity in all three trials was measured using ETDRS charts. In all three included studies there was no difference in rates of loss of visual acuity over four years between the intervention and comparison groups.

Berson 2004a reported the ETDRS visual acuity as number of letters per year. Both the groups (DHA and vitamin A) and (placebo and vitamin A) lost 0.7 letters of ETDRS visual acuity per year.

In Hoffman 2004, the mean change from baseline visual acuity after four years' follow‐up was 0.05 logMAR units (95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.14), i.e. 2.5 letters, among participants treated with DHA, and 0.06 logMAR units (95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.14) among participants treated with placebo, with less than one letter difference between the two groups (mean difference: ‐0.01 logMAR units (95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.12)).

In Berson 1993, decline in ETDRS visual acuity was 1.1 letters per year in the intervention group (vitamin A + vitamin E trace) and 0.9 letters per year in the control group (vitamin A trace + vitamin E trace), with no statistically significant difference between the groups.

Electroretinography

Two trials examined the treatment effect associated with DHA on ERG amplitudes (Berson 2004a; Hoffman 2004), and one trial examined the effect of vitamin A (Berson 1993). Both rod and cone ERG amplitudes were measured in all three trials. The results varied across the three trials.

In Berson 2004a, the effect of vitamin A and DHA on cone ERG amplitude was reported in terms of mean rate of decline of remaining 30 Hz ERG amplitude per year of follow‐up. Over four years, analysis of 30 Hz cone ERGs showed that the mean annual rates of decline of remaining function were 9.92% in the group receiving DHA and vitamin A, and 10.49% in the group taking only vitamin A; the difference was not significantly different (P value 0.64).

In Hoffman 2004, the average difference in change from baseline in cone ERG amplitude between DHA and placebo after four years' follow‐up was 0.07 log μV (95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.17). In calculating the sample size for Hoffman 2004, the trial was powered to detect an anticipated change of 0.085 log units per year in cone ERG amplitude. The observed decline in cone ERG amplitude in the control group was only 0.066 log units per year. Thus, this trial may not have been adequately powered to detect the pre‐specified treatment effect. A subgroup analysis of Hoffman 2004 reported a statistically significant effect of DHA on rod ERG amplitude, but not on cone ERG amplitude in children under 12 years of age. Conversely, they reported a statistically significant effect of DHA on cone ERG amplitude ‐ but not on rod ERG amplitude ‐ among children 12 years old or older.

In Berson 1993, the trial reported an effect of vitamin A on the mean change in log ERG amplitude from baseline that was statistically significant (P value 0.01). A previous cohort study had estimated a decline of 17% of remaining cone ERG amplitude per year among patients with RP (Berson 1985), and the Berson 1993 trial was designed using this assumption for sample size calculation. The 1985 trial report described that participants with measurable cone ERG amplitude (≥ 0.68 μV) at baseline showed a decline of 10% per year (in the trace group), whereas participants in the trace group with < 0.68 μV cone ERG amplitude did not show any measurable rate of decline in cone ERG amplitude. The authors in Berson 1993 inferred from these observations that the effects of intervention might be detected only in participants who had minimum cone ERG amplitude of 0.68 μV at baseline. Accordingly, Berson 1993 reported a post hoc subgroup analysis that included only participants who had high cone ERG amplitude at baseline. Findings from this subgroup analysis indicated that daily supplementation with 15000 IU vitamin A reduced the annual rate of loss of remaining cone ERG amplitude compared to people not receiving this dose of vitamin A (Berson 1993). This difference was statistically significant (8.3% decline per year in vitamin A group versus 10% decline per year in non‐vitamin A group; P value 0.001), although the clinical relevance of this difference is questionable. A statistically significant effect was also observed for this outcome when the analysis included all randomized patients in this trial (6.1% decline per year in vitamin A group versus 7.1% decline per year in non‐vitamin A group; P value 0.01). These findings from subgroup analyses have not been replicated or substantiated by findings in any of the remaining trials.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We did not find evidence for the benefit of treatment with vitamin A or DHA, or both, for people with RP for the outcomes pre‐specified in our protocol, with the exception of one subgroup in Berson 1993, in which participants with high cone amplitude at baseline appear to have had a reduced rate of loss of remaining cone function compared to non‐supplemented controls. The findings from this subgroup analysis have not been replicated in other RCTs. Where data were available for the mean change in visual field, visual acuity and cone ERG amplitude after four years of follow‐up in adult patients with X‐linked RP (Hoffman 2004), there was no statistically significant benefit. Berson 1993 described a statistically significant protective effect of vitamin A on the annual mean change in cone ERG amplitude.

Despite testing visual fields with two different visual field instruments, different automated strategies and outcome measures, there was no demonstrable effect of therapy on visual field outcome. Initially, Berson 1993 performed kinetic Goldmann visual fields with V‐4‐e white test light on a 601 participants aged 18 to 49 years. Comparing treatment groups and controls, there was no treatment effect on visual field area; however, the authors noted a positive trend correlating visual field area and change in 30 Hz ERG amplitude‐suggesting that participants receiving vitamin A had a slower rate of decline in visual field area over the four years of treatment.

In a follow‐up study in 2004 (Berson 2004a), the investigators studied central and peripheral visual field changes using the Humphrey Field Analyzer (HFA, Zeiss‐Humphrey Systems, Dublin, California, USA). They assessed central field with the HFA 30‐2 program and total field with the combined HFA 30‐2 and 30/60‐1 programs over three to four years. A size V target was used centrally and peripherally using the FASTPAC test. There was significant visual field loss over all the points measured in the treatment and the control groups: centrally (37 to 38 decibel (dB) per year to the HFA 30‐2 program condition) combined with overall visual field loss (57 to 60 dB to the HFA 30‐2/30/60‐1 programs combined). The trialists reported, “these total point score declines summarize about 0.5 dB and 0.4 dB per year, respectively, for an average location in the visual field”.

Hoffman 2004 studied visual fields in 21 participants in the treatment group and 23 controls using the HFA. A 30‐2 static program with spot size III was used to assess 74 locations within the central 30 degrees. Participants who had retained peripheral function were also tested at 72 locations with the 30/60‐2 program. As the trialists reported, “The visual field parameter selected for evaluation was the mean field defect (average of all differences from mean normal; dB)”, and the mean defect changed by 1.4 ± 1.32 dB in the placebo (control) group compared with 2.4 ± 3.66 dB in the treatment group. The authors expressed concern about the young age of participants doing visual field testing at the beginning of the study.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Small, non‐randomized pilot studies (for example, Tcherkes 1950 and Dagnelie 2000) have reported evidence of effectiveness of vitamins in the treatment of RP, but the three well‐designed, well‐executed RCTs included in this trial did not, either individually or collectively. The available data do not indicate a significant beneficial effect of DHA or vitamin A on progression of loss of visual acuity and visual field. Also, there was no evidence that the effects of vitamin A or combination of vitamin A and DHA differed according to the genetic profile of the participants, as assessed in Berson 1993 and Berson 2004a.

Trials included in this review enrolled participants with common forms of RP. None of the trials included participants with atypical forms of RP (e.g. paravenous retinitis pigmentosa, clumped pigmentary retinal degeneration, sector retinitis pigmentosa, or unilateral retinitis pigmentosa), most syndromic forms of RP (Refsum disease, Bardet‐Biedlsyndrome, Usher's syndrome type 1 (i.e. retinitis pigmentosa with profound congenital deafness), or retinitis pigmentosa associated with hereditary abetalipoproteinemia (i.e. Bassen‐Kornzweig syndrome)). In addition, none of the trials included pregnant women, people with weight and height under the 5th percentile for a given age and sex, those with liver malfunction, those over 55 years of age, and people with a more advanced stage of the disease (visual acuity < 20/100, central visual field diameter < 8 degrees, or people with 30 Hz cone ERG amplitude of < 0.5 μV in response to 0.5 Hz white light or < 0.12 μV in response to 30 Hz white flickering light).

Quality of the evidence

We determined that all included trials had a low risk of bias for the domains assessed. The results described in the trials are valid. However, we were unable to extract sufficient data on our outcomes specified in our protocol from the results described in the trial reports. The trials appear to have been well designed and conducted. However, the conclusions drawn from the data that supplemental vitamin A or vitamin A along with DHA slows the progression of RP were based on the findings through ERG measurements rather than visual field or visual acuity.

Potential biases in the review process

The descriptions of potential biases in the review process pertain to the current status of availability of data. We will revise our findings based on response from trial authors regarding data on outcomes. We were unable to extract data from the text, tables or figures for the outcomes specified in the protocol for this review. In one case, the mean cone ERG amplitude was available for both treatment groups from a figure, but we could not extract the standard error for the difference in mean change from baseline between the groups. Communicating with authors should not introduce selection bias in the review (Borly 2001), and may result in availability of more data for assessment, since we are working with a small number of included trials and are unlikely to be able to conduct a meta‐analysis.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review is in general agreement with other published reviews and other comments. For example, Dr Edward Norton, a member of the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee for Berson 1993, published his opinion that the data did not demonstrate a significant beneficial effect for vitamin A (Norton 1993). Similarly, Massof 2010 reviewed three RCTs, including Berson 1993 and Berson 2004a, and concluded that the results did not prove that these interventions slowed the rate of progression of RP.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Based on the results of three randomized controlled trials (RCTs), there is no clear evidence for the benefit of treatment with vitamin A or docosahexaenoic acid (extracted from fish oil), or both, for patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP), in terms of mean change in visual field and electroretinogram (ERG) amplitudes after one year, and the mean change in visual acuity at five years follow‐up.

Thus, at present there are inadequate data to recommend the use of these two interventions for patients with RP. Although the exclusion criteria across the included trials were extensive, thus limiting the applicability of evidence to many patients with RP, it is unlikely that future trials would include patients that meet these criteria. Thus, the findings from the trials included in this systematic review should be carefully considered in the management of patients that meet these exclusion criteria.

Systemic side effects or toxicity for long term supplementation of high dose vitamin A is unknown.

Implications for research.

The design and reporting of future trials on patients with RP should consider outcomes relevant to various stakeholders (e.g. patients, physicians and family members) as well as those specified in this systematic review. Some of the included trials included unplanned subgroup analysis that suggested differential effects based on previous vitamin A exposure, so investigators should consider examining this issue in future RCTs. Future trials on the effects of vitamin A and fish oils for RP should take into account the changes observed in ERG amplitudes and other outcome measure from trials included in this review, in addition to previous cohort studies, when calculating sample sizes in order to assure adequate power to detect clinically and statistically meaningful difference between treatment arms.

Acknowledgements

We thank Iris Gordon, the Trials Search Coordinator for the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (CEVG) for her help in developing and conducting the electronic searches. We thank Ann‐Margret Ervin, PhD for her critical comments on earlier versions of this protocol. We acknowledge the assistance provided by Kay Dickersin, MA, PhD at the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group US Project, funded by Grant 1 U01 EY020522‐01, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA, in developing the protocol for this review.

Richard Wormald (Co‐ordinating Editor for CEVG) acknowledges financial support for his CEVG research sessions from the Department of Health through the award made by the National Institute for Health Research to Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology for a Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Retinitis Pigmentosa #2 retina* near pigmentosa #3 tapetoretina* near degener* #4 rod near cone near dystroph* #5 pigment* near retinopath* #6 MeSH descriptor Tangier Disease #7 tangier near disease* #8 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) #9 MeSH descriptor Vitamin A #10 vitamin next A #11 MeSH descriptor Retinoids #12 retino* #13 retinyl palmitate #14 MeSH descriptor beta Carotene #15 beta carotene* #16 MeSH descriptor Fish Oils #17 fish near oil* #18 MeSH descriptor Fatty Acids, Omega‐3 #19 omega 3 #20 MeSH descriptor Docosahexaenoic Acids #21 docosahexaenoic #22 DHA #23 MeSH descriptor Eicosapentaenoic Acid #24 eicosapentaenoic #25 icosapentaenoic #26 (#9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25) #27 (#8 AND #26)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

1 randomized controlled trial.pt. 2 (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 3 placebo.ab,ti. 4 dt.fs. 5 randomly.ab,ti. 6 trial.ab,ti. 7 groups.ab,ti. 8 or/1‐7 9 exp animals/ 10 exp humans/ 11 9 not (9 and 10) 12 8 not 11 13 exp retinitis pigmentosa/ 14 (retin$ adj2 pigmentosa).tw. 15 (tapetoretina$ adj2 degener$).tw. 16 (rod adj2 cone adj2 dystroph$).tw. 17 (pigment$ adj2 retinopath$).tw. 18 exp tangier disease/ 19 (tangier adj2 disease$).tw. 20 or/13‐19 21 exp Vitamin A/ 22 vitamin A.tw. 23 exp retinoids/ 24 retino$.tw. 25 retinyl palmitate.tw. 26 exp beta carotene/ 27 beta carotene$.tw. 28 exp fish oil/ 29 (fish adj2 oil$).tw. 30 exp fatty acids,omega 3/ 31 omega 3.tw. 32 exp docosahexaenoic acids/ 33 docosahexaenoic.tw. 34 DHA.tw. 35 exp eicosapentaenoic acid/ 36 eicosapentaenoic.tw. 37 icosapentaenoic.tw. 38 or/21‐37 39 20 and 38 40 12 and 39

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville et al (Glanville 2006).

Appendix 3. EMBASE (OvidSP) search strategy

1 exp randomized controlled trial/ 2 exp randomization/ 3 exp double blind procedure/ 4 exp single blind procedure/ 5 random$.tw. 6 or/1‐5 7 (animal or animal experiment).sh. 8 human.sh. 9 7 and 8 10 7 not 9 11 6 not 10 12 exp clinical trial/ 13 (clin$ adj3 trial$).tw. 14 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 15 exp placebo/ 16 placebo$.tw. 17 random$.tw. 18 exp experimental design/ 19 exp crossover procedure/ 20 exp control group/ 21 exp latin square design/ 22 or/12‐21 23 22 not 10 24 23 not 11 25 exp comparative study/ 26 exp evaluation/ 27 exp prospective study/ 28 (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 29 or/25‐28 30 29 not 10 31 30 not (11 or 23) 32 11 or 24 or 31 33 exp retinitis pigmentosa/ 34 (retin$ adj2 pigmentosa).tw. 35 (tapetoretina$ adj2 degener$).tw. 36 (rod adj2 cone adj2 dystroph$).tw. 37 (pigment$ adj2 retinopath$).tw. 38 exp tangier disease/ 39 (tangier adj2 disease$).tw. 40 or/33‐39 41 exp Retinol/ 42 vitamin A.tw. 43 retino$.tw. 44 retinyl palmitate.tw. 45 exp beta carotene/ 46 beta carotene$.tw. 47 exp fish oil/ 48 (fish adj2 oil$).tw. 49 exp omega 3 fatty acid/ 50 omega 3.tw. 51 exp docosahexaenoic acids/ 52 docosahexaenoic.tw. 53 DHA.tw. 54 exp icosapentaenoic acid/ 55 eicosapentaenoic.tw. 56 icosapentaenoic.tw. 57 or/41‐56 58 40 and 57 59 32 and 58

Appendix 4. LILACS search strategy

fish oil or omega 3 or docsahexaenoic or eicosapentaenoic or vitamin A or retino$ or carotene$ and retinitis pigmentosa

Appendix 5. metaRegister of Controlled Trials search strategy

(Retinitis Pigmentosa) AND (fish oil OR omga 3 OR docsahexaenoic OR eicosapentaenoic OR vitamin A OR Retino OR carotene)

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

(Retinitis Pigmentosa) AND (Fish Oil OR Omga 3 OR Docsahexaenoic OR Eicosapentaenoic OR Vitamin A OR Retino OR carotene)

Appendix 7. ITCRP search strategy

retinitis pigmentosa

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Berson 1993.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

Notes: the trial was originally planned to allow for 4 years of follow‐up for each participant. However, due to slow recruitment (required 3 years), follow‐up was continued on all participants until the last randomized participants had completed their 4th year of follow‐up. The DSMB recommended cessation of this protocol in September 1991 because by then all participants had completed their 4th year of follow‐up and additional follow‐up data would probably not lead to conclusions that would be substantially more precise. The smaller sample sizes at year 5 (n = 472) and year 6 (n = 261) reflect the fact that the study was stopped after the last 4th‐year follow‐up visit. The mean duration of follow‐up was 5.2 years for all randomized participants. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “A separate set of randomization assignments was maintained for each stratum based on a computer‐generated set of random numbers to facilitate the above randomization” (p 764) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Each bottle contained 100 capsules labeled with a lot number and instructions for storage at room temperature but not labeled as to content.” (p 763) |

| Blinding of Participants | Low risk | “Patients did not know the contents of the supplements under study or their group assignment and also agreed not to know the course of their retinal degeneration until the end of the study” (p 764) |

| Blinding of Caregivers | Low risk | “All members of the staff in contact with the patients, including the principal investigator (E.L.B.), were masked as to the treatment group assignment of each patient.” (p 764) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for primary outcome (visual field) | Low risk | “All members of the staff in contact with the patients, were masked as to the treatment group assignment of each patient. Each ocular examination and ERG was performed without review of previous records” (p 764) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for secondary outcome (visual acuity) | Low risk | “All members of the staff in contact with the patients were masked as to the treatment group assignment of each patient. Each ocular examination and ERG was performed without review of previous records” (p 764) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for secondary outcome (ERG) | Low risk | “Each ocular examination and ERG was performed without review of previous records.” (p 764) |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed for primary outcome (visual field) | Low risk | “Only 5% (29/601) of patients failed to complete this study; four of these patients died and 25 patients declined to continue participation, most after the fourth year.” (p 770) |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed for secondary outcome (visual acuity) | Low risk | “Only 5% (29/601) of patients failed to complete this study; four of these patients died and 25 patients declined to continue participation, most after the fourth year.” (p 770) |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed for secondary outcome (ERG) | Low risk | “Only 5% (29/601) of patients failed to complete this study; four of these patients died and 25 patients declined to continue participation, most after the fourth year.” (p 770) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgment, as the study protocol is not available |

| Other bias | Low risk | We did not detect other bias |

Berson 2004a.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions |

Each participant received either 6 capsules/day each containing 500 mg of fatty acids (200 mg of which was DHA, for a total of 1200 mg/d of DHA), or 6 placebo capsules/day containing 500 mg of fatty acids with no DHA, for 4 years. Vitamin A was administered as retinyl palmitate. |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "A separate set of randomization assignments was maintained for each stratum based on a computer generated set of random numbers" (p 1299) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | " . . . computer generated set of random numbers that was available only to a programmer who provided assignment information to the data manager (C.W.D.) on a case‐by‐case basis. Group assignment was implemented by the data manager". (p 1299) |

| Blinding of Participants | Low risk | "Patients did not know the contents of the supplement under study or their treatment group assignment and also agreed not to know the course of their retinal degeneration until the end of the study". (p 1299) |

| Blinding of Caregivers | Low risk | "All members of the staff in contact with the patients, including the principal investigator (E.L.B.), were masked with regard to each patient’s treatment group assignment" (p 1299) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for primary outcome (visual field) | Low risk | "Each ocular examination was performed without review of previous records" (p 1299) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for secondary outcome (visual acuity) | Low risk | "Treatment group assignments and plasma DHA and RBC PE DHA levels were placed in records separate from that used for ocular examinations as part of masking those in contact with the patients" (p 1299) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for secondary outcome (ERG) | Low risk | "Treatment group assignments and plasma DHA and RBC PE DHA levels were placed in records separate from that used for ocular examinations as part of masking those in contact with the patients" (p 1299) |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed for primary outcome (visual field) | Low risk | "Two hundred eight of these patients (221) completed all 4 annual follow‐up visits. Analyses performed on patients with partial follow‐up, but with missing values left as missing and after using multiple imputation methods to account for missing data among patients with incomplete followup". (p 1301) |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed for secondary outcome (visual acuity) | Low risk | "Two hundred eight of these patients (221) completed all 4 annual follow‐up visits. Analyses performed on patients with partial follow‐up, but with missing values left as missing and after using multiple imputation methods to account for missing data among patients with incomplete followup". (p 1301) |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed for secondary outcome (ERG) | Low risk | "Two hundred eight of these patients (221) completed all 4 annual follow‐up visits. Analyses performed on patients with partial follow‐up, but with missing values left as missing and after using multiple imputation methods to account for missing data among patients with incomplete followup". (p 1301) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Study protocol is not available |

| Other bias | Low risk | We did not detect other bias |

Hoffman 2004.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions |

Each participant received 2 capsules/day each containing 500 mg of fatty acids (200 mg of which was DHA, for a total of 400 mg/d of DHA), or 2 placebo capsules/day containing 500 mg of fatty acids with no DHA, administered for 4 years |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Placebo and + DHA assignments were made following a block randomization schedule (10/block).” (p 705) Method used for random sequence generation is unclear |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Relatives were randomized together to eliminate a potential for mixing of capsules; there were five sib‐pairs in each cohort” (p 705) |

| Blinding of Participants | Low risk | “All medications were labeled either A or B by the manufacturer. Both study oils were encapsulated with ethyl vanillin‐flavored gelatin; thus, smell and taste of the capsules were identical.” (p 705) |

| Blinding of Caregivers | Low risk | “Martek retained the code and divulged group assignment to the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee when requested to or to a patient’s physician in case of a medical emergency.” (p 705) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for primary outcome (visual field) | Low risk | “The randomization code was not available to study personnel conducting visual function assessments until after completion of testing.” (p 705) |

| Blinding outcome assessors for secondary outcome (visual acuity) | Low risk | “The randomization code was not available to study personnel conducting visual function assessments until after completion of testing.” (p 705) |