Abstract

We analyzed the presenting features and survival in 1689 patients with multiple myeloma aged younger than 50 years compared with 8860 patients 50 years of age and older. Of the total 10 549 patients, 7765 received conventional therapy and 2784 received high-dose therapy. Young patients were more frequently male, had more favorable features such as low International Staging System (ISS) and Durie-Salmon stage as well as less frequently adverse prognostic factors including high C-reactive protein (CRP), low hemoglobin, increased serum creatinine, and poor performance status. Survival was significantly longer in young patients (median, 5.2 years vs 3.7 years; P < .001) both after conventional (median, 4.5 years vs 3.3 years; P < .001) or high-dose therapy (median, 7.5 years vs 5.7 years; P = .04). The 10-year survival rate was 19% after conventional therapy and 43% after high-dose therapy in young patients, and 8% and 29%, respectively, in older patients. Multivariate analysis revealed age as an independent risk factor during conventional therapy, but not after autologous transplantation. A total of 5 of the 10 independent risk factors identified for conventional therapy were also relevant for autologous transplantation. After adjusting for normal mortality, lower ISS stage and other favorable prognostic features seem to account for the significantly longer survival of young patients with multiple myeloma with age remaining a risk factor during conventional therapy.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma is uncommon in young persons. The incidence increases steadily with increasing age to a peak age-specific incidence of more than 40 per 100 000 in persons older than 80 years.1,2 Whether the presentation and prognosis of multiple myeloma in young patients differs from the disease usually encountered in the typical elderly patient has only rarely been addressed and never in a large patient cohort. A previous study in 61 patients aged younger than 50 years showed no difference in presenting features compared with older patients.3 Survival was significantly better compared with the older patient cohort but was significantly shorter in young patients after findings were corrected for differences in life expectancy.3 Blade et al reported an increased frequency of renal impairment (30%) and hypercalcemia (29%) at presentation and median survival of 54 months in 72 patients younger than 40 years.4 The question regarding differences in presentation and in outcome in different age groups is clinically relevant since significant differences in prognostic and biologic features have been demonstrated in several other malignancies. Prognosis is significantly better in young patients with acute myeloid leukemia who have less frequently adverse cytogenetic abnormalities,5 but significantly worse in young patients with breast cancer whose tumors are less frequently hormone responsive.6

Here, we report the presenting features and outcome after conventional and high-dose therapy in 10 549 patients with myeloma and compare the findings obtained in 1689 patients younger than 50 years of age with those of 8860 older patients.

Methods

A total of 17 institutions and/or study groups from North America, Europe, and Japan participated in this study. A total of 1006 patients were entered from the Japanese myeloma study group, 6457 from European centers (Austria, Spain, France, Italy, Nordic countries, Turkey, and the United Kingdom), and 2386 from North America (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG], National Cancer Institute of Canada [NCIC], Mayo Clinic, Princess Margaret Hospital, Southwest Oncology Group [SWOG], and University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences [UAMS]). Informed consent and approval by the local institutional review board (IRB) were fulfilled as requested at the time of patient enrollment at each participating center. Patients were started on therapy between 1981 and 2002, and part of the information collected was previously used as basis for the generation of the International Staging System (ISS).7 Survival status and date of last follow-up were available for 10 750 patients. A total of 23 of those patients were excluded due to unknown age, and 178 were excluded because life tables for their countries were not available, leaving 10 549 patients for inclusion in this analysis. A total of 7765 patients received conventional chemotherapy as first-line treatment, and 2784 patients were subjected to high-dose therapy with planned autologous stem-cell transplantation. The 730 patients who received high-dose treatment as second or later line of therapy were included in the conventional therapy arm. Of the 10 549 patients, 7413 (70%) had been enrolled into clinical trials. The median age of patients enrolled in clinical trials was 60 years, and that of the other patients was 63 years. Median follow-up was 3.25 years (maximum, 19.21 years).

Standard criteria were applied for diagnosis of multiple myeloma.8 Patients with smouldering (asymptomatic) myeloma, amyloidosis, and monoclonal IgM-related disorders were not included.

In addition to these cited data, the following information was available: date of start of therapy; sex; ethnicity; race; performance status; hemoglobin level; platelet count; level and type of paraprotein; and serum levels of calcium, creatinine, albumin, LDH, β2-microglobulin, and C-reactive protein (CRP). Stage was assessed according to the ISS and the Durie-Salmon system. Furthermore, the percentage of bone marrow plasma cell infiltration and the number of osteolytic lesions was recorded. In 522 patients, conventional cytogenetics was available. Del 13 was assessed by conventional cytogenetics in 454 patients and by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in 373 patients.

The chi-square test was used to determine significant prognostic factors that distinguish younger from older patients. A maximum likelihood model was used to estimate relative excess risk (RER) for younger versus older patients treated with conventional or high-dose treatment, using a generalized linear model approach with Poisson error structure using exact survival times and collapsed data, as described by Dickman et al.9 To determine these estimates, the observed survival was adjusted by dividing by life expectancy depending on age, sex, year of diagnosis, and nationality. Relative survival adjustment was done in order to compare survival between young and old, while taking the normal mortality expectations of respective populations into account. Life tables of estimated population mortality rates for the country of each treating institution were obtained from the Human Mortality Database.10 Estimates of overall survival within age groups were produced using the Kaplan-Meier method,11 and were compared using the log-rank test.12 Cox regression analysis13 was used to develop a multivariate model of prognostic factors using a stepwise approach considering those factors that were associated univariately with survival with a P value of .01 or less. The final model was then adjusted for relative survival to estimate the RER for each prognostic factor.

Results

Median age of all 10 549 patients combined was 60 years. Of these, 1689 (16%) patients were younger than 50 years. Of those, most (1377 [82%] of 1689) were between 40 to younger than 50 years of age. Only 312 patients were younger than 40 years, and 27 patients were younger than 30 years. Median age of the 8860 patients 50 years or older was 62 years (range, 50-93 years), and the median age of the 1689 patients less than age 50 years was 36 years (range, 20-49 years).

The presenting features of patients younger than 50 years of age versus 50 years and older are shown in Table 1. The younger patients were more frequently ECOG performance status 0 to 1 (64% vs 57%; P < .001) and more likely to have ISS stage I (39% vs 26%; P < .001), but less often intermediate (stage II: 35% versus 39%; P < .001) or advanced ISS stage (stage III: 27% vs 34%; P < .001). In addition, young patients presented less often with the adverse prognostic factors low serum albumin (< 35 g/L [< 3.5 g/dL]) and high β2-microglobulin (≥ 3.5 mg/dL]) serum levels (33% vs 41% and 45% vs 59%; P < .001 and P < .001, respectively). Likewise, low hemoglobin (< 10 g/dL; 37% versus 41%; P = .006), elevated CRP (24% versus 29%; P < .007), and increased serum creatinine (≥ 2 mg/dL; 15% vs 17%; P < .028) were less common in the patients younger than 50 years. All other prognostically relevant laboratory variables investigated, including serum calcium, LDH, bone marrow plasma cell infiltration, and hematologic variables, did not differ significantly between the 2 groups. Frequency of IgA isotype was slightly lower (21% vs 25%; P < .001) and that of light chain myeloma was slightly higher (13% vs 10%; P < .002) in the young age cohort.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, laboratory parameters, and cytogenetic findings in patients younger than 50 years and patients 50 years or older

| Factor | Age category |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger than 50 y, no. (%) | At least 50 y, no. (%) | ||

| Male | 1023/1689 (61) | 5014/8860 (57) | .002 |

| Performance status 2+ | 562/1582 (36) | 3603/8328 (43) | < .001 |

| ISS | |||

| Stage I | 492/1267 (39) | 1790/6776 (26) | < .001 |

| Stage II | 438/1267 (35) | 2675/6776 (39) | < .001 |

| Stage III | 337/1267 (27) | 2311/6776 (34) | < .001 |

| Durie-Salmon stages I or II | 612/1530 (40) | 3669/7731 (47) | < .001 |

| Stage I | 108/1333 (8) | 494/6168 (8) | .910 |

| Stage II | 307/1333 (23) | 1612/6168 (26) | .019 |

| Stage III | 918/1530 (60) | 4062/7731 (53) | < .001 |

| Subtype A | 1422/1676 (85) | 7198/8800 (82) | .003 |

| IgG | 924/1538 (60) | 4853/8091 (60) | .943 |

| IgA | 318/1538 (21) | 2009/8091 (25) | < .001 |

| IgD | 43/1538 (3) | 251/8091 (3) | .522 |

| Light chain only | 197/1538 (13) | 824/8091 (10) | .002 |

| Measurable M-protein | 1091/1340 (81) | 6695/7754 (86) | < .001 |

| More than 3 lytic lesions | 617/1292 (48) | 3457/7423 (47) | .431 |

| No bone lesions | 293/1387 (21) | 1756/8000 (22) | .492 |

| β2M ≥3.5 mg/dL (≥0.2975 μM) | 613/1377 (45) | 4141/7061 (59) | < .001 |

| Albumin <3.5 g/dL | 458/1396 (33) | 3276/7912 (41) | < .001 |

| HGB <10 g/dL | 596/1614 (37) | 3465/8539 (41) | .006 |

| Creatinine ≥2 mg/dL (≥76.8 μM) | 240/1594 (15) | 1484/8573 (17) | .028 |

| Platelets <(130 × 103)μL | 152/1420 (11) | 984/8168 (12) | .148 |

| Calcium ≥10 mg/dL (≥2.5 mM) | 481/1445 (33) | 2652/7870 (34) | .762 |

| CRP 0.8 mg/dL or more | 169/695 (24) | 1099/3740 (29) | .007 |

| Bone marrow plasma cells 33% or more | 892/1544 (58) | 4877/8250 (59) | .325 |

| LDH above normal | 158/600 (26) | 888/3365 (26) | .977 |

Where conventional units of measure are given in column 1, SI units follow in parentheses.

The group of young patients was further split into a subgroup of very young patients (< 40 years of age) and a subgroup of patients aged 40 to less than 50 years. Table 2 shows a comparison of those parameters, which were found to differ between these age groups. The patients younger than 40 years of age are even more likely to be male (67%), plus have better performance status and lower/better staging.

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory features, which showed significant different frequencies between the very young (< 40 years old) and the young (40 to < 50 years old) patients

| Factor | Age category |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger than 40 y | 40 to younger than 50 y | ||

| Male | 208/312 (67) | 815/1377 (59) | .015 |

| Performance status 2+ | 87/296 (29) | 475/1286 (37) | .014 |

| ISS stage II | 63/219 (29) | 375/1048 (36) | .047 |

| Durie-Salmon subtype A | 252/310 (81) | 1170/1366 (86) | .053 |

| Platelets less than 130 × 109/L | 36/247 (15) | 116/1173 (10) | .030 |

Data are number with factor/number with valid data for factor (%)

Median follow-up was 3.25 years (maximum, 19 years) in the entire cohort, 4.09 years (maximum, 19.07 years) in the young patients, and 3.08 years (maximum, 19.21 years) in the patients aged 50 years or older. Relative excess risk of death was significantly higher in older patients (median adjusted for relative survival, 3.7 years vs 5.2 years; RER, 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12-1.42; P ≤ .001), but did not differ between males and females in the respective groups (median [males vs females], ≥ 50 years, 3.7 years vs 3.7 years; RER, 1.05, 95% CI, 0.996-1.116; P = .07; median < 50 years, 5.2 years vs 4.7 years; RER, 0.98, 95% CI, 0.09-1.12; P = .81; Figure 1A,B).

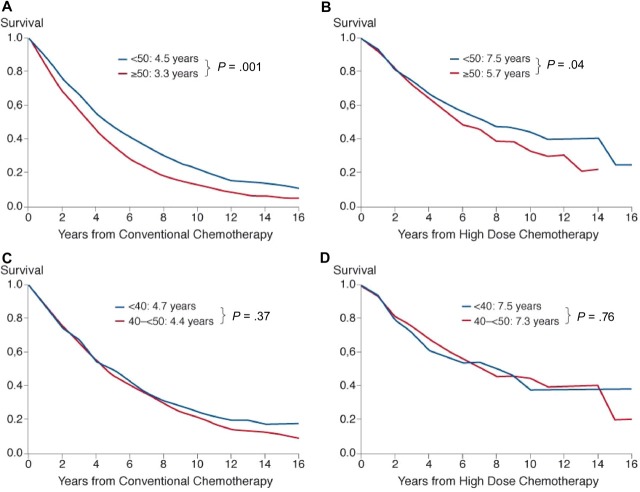

Figure 1.

Cumulative relative survival in the entire sample of 10 549 patients stratified by age (A), age and sex (B), age and ISS stage (C), and age and performance status (D) in all patients, in patients treated with conventional therapy stratified by age and stage (Ci) and age and performance status (Di), and in patients treated by high-dose therapy stratified by age and stage (Cii) and age and performance status (Dii). Inserts show median values adjusted for relative survival and P values.

Better outcome in the younger cohort was seen in all 3 ISS stages (Figure 1C) and was independent of sex. Better ECOG performance status (≤ 1) was associated with significantly extended survival, both in the younger (median, 5.5 years vs 4.2 years; RER, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.64-0.84; P < .001), and in the older cohort (median, 4.2 years vs 2.8 years; RER, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.63-0.71; P < .001; Figure 1D). This important interaction between younger age and stage as well as performance status was most obvious in patients treated with conventional therapy (Figure 1Ci,Di), where it was statistically significant versus in those patients treated with high-dose therapy (Figure 1Cii,Dii), for whom it was not statistically significant.

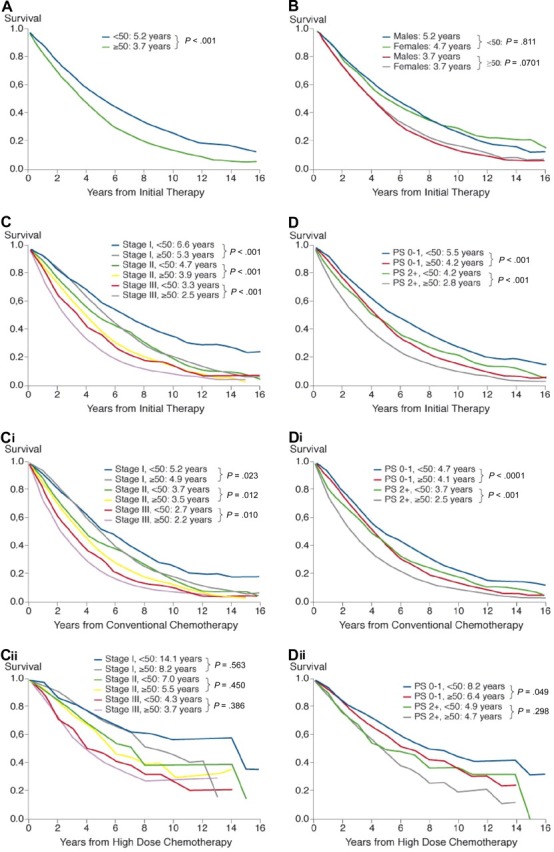

Relative excess risk of death was significantly higher after conventional treatment in the older cohort (median, 3.3 years vs 4.5 years; RER, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.32-1.55; P < .001; Figure 2A). This was also reflected by a significantly higher observed 10-year survival rate (19% vs 8%; log-rank P < .001) in the younger patients.

Figure 2.

Cumulative relative survival in patients treated with conventional therapy (A) and high-dose therapy (B) in patients younger than 50 years or 50 years and older and in patients younger than 40 years or 40 years and older (C,D). Inserts show median values adjusted for relative survival and P values.

High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation resulted in a higher relative excess risk of death in the older patients (median survival, 5.7 years) compared with the younger patients (median survival, 7.5 years; RER, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01-1.36; P = .04; Figure 2B). Similarly, the observed 10-year survival rate was significantly higher in the younger patients (43% vs 29%; log-rank P = .005). Relative survival was similar in the subgroup of patients aged 40 to less than 50 years versus that of very young patients, both after conventional chemotherapy (4.4 years vs 4.7 years; Figure 2C) and after autologous transplantation (7.3 years vs 7.5 years; RER estimates, 1.09 and 0.93, respectively; Figure 2D). The 10-year survival rates were also similar, both after conventional (21% vs 19%; P = .37) and after high-dose treatment (44% vs 38%; P = .76 by log-rank test).

Conventional therapy was given to 994 (58.9%) of the 1689 patients aged younger than 50 years and to 6771 (76.4%) of the older patients, while high-dose therapy was administered to 695 (41.1%) of the younger patients and to 2089 (23.6%) of the older patients, respectively. The percentage of young patients enrolled during different time periods for treatment with conventional therapy decreased from 94.2% in the period between 1981 and 1987 to 21.3% in the years between 1999 and 2002 (P < .001), while the proportion of those subjected to high-dose therapy increased from 5.7% to 78.7% (P < .001; Table 3). The respective figures for older patients were 98.8% to 40.1% (P < .001) for conventional therapy, and 1.2% to 59.9% (P < .001) for high-dose therapy.

Table 3.

Proportion of patients younger than 50 years old versus older than 50 years old treated with either conventional or high-dose therapy during different time periods

| Treatment | Time period, no. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 to 1987 | 1988 to 1992 | 1993 to 1998 | 1999 to 2002 | |

| Younger than 50 y | ||||

| Conventional therapy | 197 (94.2) | 455 (83.9) | 299 (40.6) | 43 (21.3) |

| High-dose therapy | 12 (5.7) | 87 (16.1) | 437 (59.4) | 159 (78.7) |

| 50 y or older | ||||

| Conventional therapy | 1.107 (98.8) | 3.223 (97.4) | 2.003 (60.0) | 438 (40.1) |

| High-dose therapy | 13 (1.2) | 86 (2.6) | 1.336 (36.4) | 654 (59.9) |

*Chi-square test for equal proportions; all P values were less than .001.

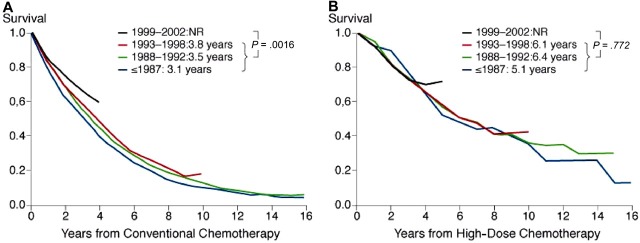

Analysis of patient characteristics by different time periods of enrollment (1981-1986, 1987-1992, 1993-1998, and 1999-2002) revealed a significant improvement of most risk factors over time (Table 4). This effect was almost exclusively seen in patients aged 50 years and older (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), while in the younger cohort, no variation of the frequency of poor prognostic features over time of enrollment was observed. Comparison of relative survival between different time periods of enrollment revealed a significant improvement in outcome for patients receiving conventional therapy during the period between 1999 and 2002 (median relative survival not reached vs 3.3 years for the earlier periods; P < .001) compared with earlier enrollment periods (Figure 3A). In patients treated with high-dose therapy, relative survival remained constant during the entire period of enrollment (Figure 3B). Both comparisons remain valid even if censoring at 2 or 4 years.

Table 4.

Change of patient characteristics by time period of enrollment

| Factor | Cohort, no. with factor/no. with valid data for factor (%) |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 to 1987 | 1988 to 1992 | 1993 to 1998 | 1999 to 2002 | ||

| Male | 642/1120 (57) | 1855/3309 (56) | 1898/3339 (57%) | 619/1092 (57%) | .870 |

| Performance status 2+ | 532/1093 (49) | 1389/3229 (43) | 1274/2959 (43%) | 408/1047 (39%) | < .001 |

| ISS | |||||

| Stage I | 131/718 (18) | 639/2622 (24) | 794/2607 (30) | 226/829 (27) | < .001 |

| Stage II | 270/718 (38) | 1056/2622 (40) | 1004/2607 (39) | 345/829 (42) | .225 |

| Stage III | 317/718 (44) | 927/2622 (35) | 809/2607 (31) | 258/829 (31) | < .001 |

| Durie-Salmon stages I or II | 418/961 (43) | 1546/3052 (51) | 1278/2719 (47) | 427/999 (43) | < .001 |

| Stage I | 31/657 (5) | 195/2306 (8) | 182/2273 (8) | 86/932 (9) | .007 |

| Stage II | 83/657 (13) | 605/2306 (26) | 650/2273 (29) | 274/932 (29) | < .001 |

| Stage III | 543/961 (57) | 1506/3052 (49) | 1441/2719 (53) | 572/999 (57) | < .001 |

| Subtype A | 835/1117 (75) | 2671/3301 (81) | 2790/3310 (84) | 902/1072 (84) | < .001 |

| IgG | 559/1011 (55) | 1864/2969 (63) | 1799/3091 (58) | 631/1020 (62) | < .001 |

| IgA | 231/1011 (23) | 742/2969 (25) | 797/3091 (26) | 239/1020 (23) | .191 |

| IgD | 48/1011 (5) | 93/2969 (3) | 97/3091 (3) | 13/1020 (1) | < .001 |

| Light chain only | 138/1011 (14) | 229/2969 (8) | 333/3091 (11) | 124/1020 (12) | < .001 |

| Measurable M-protein | 894/1029 (87) | 2284/2603 (88) | 2686/3120 (86) | 831/1002 (83) | .002 |

| More than 3 lytic lesions | 388/854 (45) | 1258/2772 (45) | 1354/2834 (48) | 457/963 (47) | .264 |

| No bone lesions | 200/953 (21) | 659/2943 (22) | 684/3110 (22) | 213/994 (21) | .798 |

| β2M ≥3.5 mg/dL (≥0.2975 μM) | 515/724 (71) | 1674/2636 (64) | 1467/2790 (53) | 485/911 (53) | < .001 |

| Albumin <3.5 g/dL | 488/1084 (45) | 1308/3131 (42) | 1112/2828 (39) | 368/869 (42) | .010 |

| HGB <10 g/dL | 410/1093 (38) | 1267/3119 (41) | 1339/3263 (41) | 449/1064 (42) | .127 |

| Creatinine ≥2 mg/dL (≥176.8 μM) | 244/1103 (22) | 596/3175 (19) | 487/3249 (15) | 157/1046 (15) | < .001 |

| Platelets <(130 × 103) μL | 115/1084 (11) | 333/3133 (11) | 377/2918 (13) | 159/1033 (15) | < .001 |

| Calcium ≥10 mg/dL (≥2.5 mM) | 404/1053 (38) | 915/2791 (33) | 986/3020 (33) | 347/1006 (34) | .004 |

| CRP 0.8 mg/dL or more | 7/33 (21) | 312/1103 (28) | 529/1872 (28) | 251/732 (34) | .010 |

| Bone marrow plasma cells 33% or more | 665/1032 (64) | 1810/3049 (59) | 1832/3141 (58) | 570/1028 (55) | < .001 |

| LDH above normal | 63/195 (32) | 182/616 (30) | 491/1939 (25) | 152/615 (25) | .034 |

Where conventional units of measure are given in column 1, SI units follow in parentheses.

Figure 3.

Cumulative relative survival in patients treated during different times of enrollment. (A) Relative survival of conventionally treated patients was significantly longer in those enrolled between 1999 and 2002 compared with patients enrolled earlier (P < .001). (B) Relative survival in patients treated with high-dose therapy was similar during the different time periods of enrollment. Inserts show median values adjusted for relative survival and P values.

Conventional cytogenetic analysis was available in 522 patients and showed no difference in the frequency of any cytogenetic abnormality (Table 5). Likewise, no significant difference in the proportion of patients with a del 13, determined either by conventional cytogenetics (454 patients) or by FISH (373 patients), was noted in the 2 age cohorts.

Table 5.

Cytogenetic findings in patients younger than 50 years of age versus those 50 years and older

| Factor | Age category, no. with factor/no. with valid data for factor (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger than 50 y | At least 50 y | ||

| Any clonal CA | 30/116 (26) | 117/406 (29) | .533 |

| Del13 by cytogenetics | 17/109 (16) | 45/345 (13) | .499 |

| Del13 by FISH | 32/53 (60) | 150/320 (47) | .069 |

CA indicates cytogenetic abnormality.

All factors with no more than 15% of values missing (Table 1) were tested in a Cox regression analysis for their prognostic relevance (data not shown). Parameters that in univariate analysis correlated with survival with a significance level of P less than or equal to .01 were then considered in a multivariate analysis. Only patients with nonmissing values on all factors were included in the multivariate analysis, reducing the actual number of patients analyzed to 3484 (45%) for those treated with conventional chemotherapy and to 1654 (59%) for those subjected to high-dose therapy. Overall survival between the patients included and those excluded from the multivariate analysis was comparable taking differences by region and time period into account. Of the factors included in multivariate analysis, both higher ISS and Durie-Salmon stage, absence of IgA isotype, higher creatinine (≥ 2 mg/dL) and low platelet count (< 130 × 109/L) were identified as independent risk factors for short survival both in patients treated by conventional or high-dose therapy. In patients started on conventional therapy, older age, performance status, presence of serum M-protein, low hemoglobin (< 10 g/dL), and bone marrow plasma cell infiltration (≥ 33%) were recognized as additional independent prognosticators for poor outcome (Table 6).

Table 6.

RER for factors that were found to correlate independently with survival in multivariate analysis

| Factor | Level | RER | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional therapy | ||||

| ISS stage (reference stage I) | Stage II | 1.26 | 1.12-1.41 | |

| ISS stage (reference stage I) | Stage III | 1.53 | 1.34-1.74 | < .001 |

| Performance status | 2+ vs 0-1 | 1.31 | 1.20-1.43 | < .001 |

| Durie-Salmon stage | III vs I or II | 1.24 | 1.14-1.36 | < .001 |

| Platelets | < 130 × 109/L vs ≥ 130 × 109/L | 1.38 | 1.21-1.56 | < .001 |

| Bone marrow plasma cell | ≥ 33% vs < 33% | 1.23 | 1.12-1.34 | < .001 |

| Age | 50+ y vs < 50 y | 1.24 | 1.08-1.41 | .001 |

| Hemoglobin | < 100 vs ≥ 100 g/L | 1.14 | 1.04-1.25 | .006 |

| IgA isotype | Present vs absent | 1.20 | 1.06-1.36 | < .001 |

| Creatinine | ≥ 176.8 μM vs < 176.8 μM | 1.20 | 1.36-1.07 | .003 |

| Serum M protein | Measurable vs not measurable | 0.79 | 0.68-0.92 | .002 |

| High-dose therapy | ||||

| ISS stage (reference stage I) | Stage II | 1.56 | 1.23-1.97 | < .001 |

| ISS stage (reference stage I) | Stage III | 2.00 | 0.52-2.63 | |

| Platelets | < 130 × 109/L vs > 130 × 109/L | 1.72 | 1.35-2.21 | < .001 |

| Durie-Salmon stage | III vs I or II | 1.32 | 1.08-1.61 | .007 |

| IgA isotype | Present vs absent | 1.31 | 1.07-1.60 | .008 |

| Creatinine | ≥ 176.8 μM vs < 176.8 μM | 1.38 | 1.06-1.79 | .015 |

| Age* | 50+ y vs < 50 y | 1.17 | 0.95-1.43 | .122 |

Patients treated with conventional chemotherapy: n = 3484 with nonmissing values on all factors, 45% of 7765 patients; patients treated with high-dose therapy: n = 1654 patients with nonmissing values for all factors, 59% of 2784 patients.

Not significant, but included for comparison.

Discussion

The most important finding in this study on 10 549 patients with multiple myeloma was the significant differences in the presenting features between young and older patients. Young patients presented with a significantly lower ISS stage and consequently had less frequently elevation of β2-microglobulin and reduction of low serum albumin levels (Table 1). In addition, significantly fewer younger patients presented with poor performance status, anemia, renal impairment, or increased CRP levels. Older patients, in contrast, had a greater prevalence of less favorable prognostic factors. Hence, both a lower ISS stage at diagnosis and overall better prognostic factors seem to account for the superior survival in young patients treated with high-dose therapy after correction for differences in life expectancies, with age remaining an independent risk factor for patients treated with conventional therapy (Table 6). Another relevant finding of this study is the low proportion of young patients observed in the entire group of patients studied, a phenomenon that had been addressed in some prior studies.3,4,14 In our investigation, 16% of the patients were younger than 50 years, 3% were younger than 40 years, and 0.26% were younger than 30 years.

The proportion of young patients treated with high-dose therapy was almost twice as high (41.1%) as that of older patients (23.6%; P < .001), and increased steadily during the period patients were enrolled into the various trials (Table 4). A similar, albeit less pronounced increase was seen for older patients reflecting the change in treatment practice with increasing usage of high-dose therapy also in older patients during recent decades.

Young age was found to be significantly associated with longer survival, both after conventional therapy (median, 4.5 years vs 3.7 years; P < .001; Figure 2A) and high-dose therapy (median, 7.5 years vs 5.7 years; P = .04; Figure 2B). Similar results with high-dose therapy were recently reported by the Nordic Myeloma Study Group.15 They observed significantly longer survival after high-dose therapy in patients younger than 60 years compared with those aged 60 to 64 years (66 months vs 50 months; P < .001), although response rates were similar in both cohorts. The data were, however, not corrected for differences in general life expectancy between these age groups. Other studies such as the analysis of the data of International Blood and Bone Marrow Registry16 in patients aged younger than 60 years and 60 years and older, and data from Little Rock17 in patients aged younger than 65 years or 65 years and older, in contrast, did not reveal significant differences in survival between younger and older patients. Selection of particularly fit elderly patients and/or shorter follow-up in the latter 2 studies may explain the favorable outcome of these comparisons.

Another interesting finding is the high 10-year observed survival rate observed in both the younger and older patients (43% vs 29%; log-rank P = .005) after high-dose chemotherapy. The 10-year survival rates were also significantly higher in the younger patient cohort (19% vs 8%; P < .001) subjected to conventional chemotherapy for first-line treatment. These figures are impressive, given the fact that data collection for this study ended before widespread use of thalidomide and the introduction of bortezomib and lenalidomide.

The proportion of patients with favorable prognostic factors increased during the entire enrollment period from 1982 to 2002, with significantly more patients presenting with lower ISS stage and better performance status in the later enrollment periods (Table 4). This effect was almost exclusively seen in the older patients (Table S1) and might be the main reason for the significant improvement in survival of the patients treated with conventional therapy during the latest enrollment period (1999-2002) compared with those enrolled earlier (1982-1998; Figure 3A). Further, better therapy at relapse, with some patients receiving thalidomide and a few even receiving bortezomib as salvage treatment, greater usage of stem cell transplantation after relapse from conventional therapy, and improved supportive care also might have contributed to the increase in survival. The absence of an increase in almost all favorable prognostic factors in the younger patients (Table S2) over the various time periods might mainly explain why survival did not improve during the last enrollment phase in patients treated with high-dose therapy (Figure 3B). As follow-up was significantly shorter in the young cohort (P < .001), the impact of recent improvements in second-line treatment and supportive care on survival may only become apparent after longer follow-up. A recent population based study from Sweden reported an improvement in 1-year relative survival ratios over 4 calendar periods from 1973 to 2003 in all age groups of patients with multiple myeloma.18 Information about treatment, however, was not available in individual patients. The 5- and 10-year survival ratios increased only in patients younger than 60 and 70 years. A similar increase in 5- and 10-year relative survival was recently found for the United States analyzing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.19 In accordance with the report from Sweden, improvement in survival was only seen in patients younger than 70 years, with highest gains observed in those younger than 50 years of age.

The similar relative and actual 10-year survival (26% vs 24%; P ≤ .57 by the log-rank test) in the subgroup of very young patients aged younger than 40 years and in the young patients aged between 40 and less than 50 years is noteworthy (Figure 2C,D) and prompted us to combine both groups for further analysis. Nevertheless, the very young patient group presented with slightly lower frequency of poor ECOG performance status (≥ 2) and ISS stage II (Table 2), but high-dose therapy was given to a similar proportion of patients of the very young and young cohort (41.5% vs 39.4%; chi-squared P = .49). Blade et al previously reported a 10-year survival rate of 13% in patients aged younger than 40 years and of 31% in a small series of patients aged younger than 30 years.20

Significantly more young patients were male compared with older patients. The preponderance of multiple myeloma in male patients is well known, but our data are surprising because a male predominance was found in 67% of the very young (younger than 40 years) and in 59% of the patients aged 40 to younger than 50 years compared with 57% in those older than 50 years. Experimental mineral oil–induced plasmocytoma occurs more frequently in male mice and 2-methoxyestradiol, an estrogen derivate, has been shown to exert antimyeloma activity both in cell lines and in myeloma-bearing mice.21 Whether increased androgenic sex hormone levels in young males do account for the preponderance of multiple myeloma in very young male adults, however, remains speculative as yet. Overall survival, however, did not differ between male and female patients, which is in contrast to several other cancers such as chronic myeloid leukemia,22 acute myeloid leukemia,23 and others that show significantly longer survival in female patients.

The frequency of cytogenetic abnormalities was very similar in the younger-than-50-years cohort and in the older-age cohort (26% vs 29%; P = .533). Of note, del 13 was found in 16% by conventional cytogenetics and in 60% by FISH in the young patients, and correspondingly in 13% and 47% in the older patients (P = .499 and P = .069, respectively; Table 5). This agrees with previous findings obtained in 2 smaller studies that did not reveal any association between cytogenetic aberrations and age in a cohort of 75 patients24 and in another group of 172 patients.25 In the latter study, similar frequencies of chromosomal aberrations have been observed in 3 cohorts of patients with different age definitions (younger than 45 years, 45 to 70 years, and older than 70 years) and in all ISS stages. This is in disagreement with a report that indicated a decreasing frequency of IgH translocations with increasing age.26 In our cohort, other parameters such as LDH and bone marrow plasma cell infiltration, which also reflect characteristics of the biology of the myeloma cell population, were evenly distributed between the 2 age cohorts, indicating an absence of a major difference in the biology of the myeloma clone between young or older patients. A similar conclusion has already previously been proposed in a study that compared survival in patients younger or older than 65 years. Differences in absolute survival between these groups disappeared after correction for differences in life expectancy and calculation of relative survival.27

It is also noteworthy that serum calcium and serum creatinine did not differ between the young and very young patients. Blade et al reported in an analysis of 72 patients with myeloma younger than 40 years a relatively high incidence of hypercalcemia (30%) and renal impairment (creatinine level, ≥ 177 μM; 29%), which was not seen in our patients. They also observed a high frequency (32%) of light chains as the only paraprotein in their young patients, which agrees to some extent with our findings, which also revealed a higher, but less pronounced prevalence of light chain disease in patients aged 50 years or less (13% vs 10%; P < .002). As in our study, other laboratory characteristics were similar to those of the general myeloma population. In spite of the high incidence of initial hypercalcemia in their patients, median overall survival was nevertheless found to be 54 months.4

The selection of patients for the current analysis was based upon enrollment into clinical studies, including high-dose therapy; hence, the median age overall is lower than the general population of patients with myeloma, with a median age of 65 to 70 years at presentation.28,29 However, a higher median age of the entire population would, if anything, have increased the difference in presenting features, which were noted as an important finding in these various analyses.

Multivariate analysis was conducted in patients with nonmissing values on all factors, reducing the number of patients included in the analysis to 3484 (45%) for those treated with conventional therapy and to 1654 (59%) subjected to high-dose therapy. As overall survival rates between the patients included and those excluded from the multivariate analysis were comparable after correcting for differences by region and by time period, there seems to be no reason to assume that the patient characteristics were different. In patients treated with conventional chemotherapy, 10 parameters were identified as independent risk factors for shortened survival by multivariate analysis (Table 6). Only 5 of these, namely ISS and Durie-Salmon stage, platelet counts, creatinine, and IgA isotype were also identified as independent risk factors in patients treated with high-dose therapy (Table 6). Hence, high-dose therapy seems to overcome the negative impact of some of the unfavorable prognostic factors, including age. The latter finding may be biased by the mode of patient selection for high-dose therapy, as only older patients deemed to be healthy enough for this procedure actually will undergo transplantation. The favorable prognostic importance of a lower ISS stage is expected and has been confirmed in other studies.30 The finding of an IgA isotype, increased serum creatinine, and low platelet counts has previously been reported as prognostically relevant,31,32 but the role of these factors is now firmly established due to the large number of patients included in our study.

In conclusion, patients with myeloma younger than 50 years of age had significantly longer age-adjusted survival both after conventional and high-dose therapy (5.4 and 7.5 years, respectively) in relation to older patients (3.7 and 5.7 years, respectively). Given the fact that thalidomide and other new drugs were not available for most patients, the 10-year survival rate was remarkably high in young patients after conventional (19%) and high-dose therapy (43%). The major factors accounting for this improved outcome of young patients were presentation with a lower ISS stage at diagnosis and other more favorable prognostic features.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the International Myeloma Foundation (Los Angeles, CA).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: H.L. and B.G.M.D. submitted, analyzed, and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript. V.B. and J.C. analyzed data and commented on the manuscript. I.T., R.A.K., J.B., R.F., MD, K.S., J.S.M., J.W., J.-L.H., M.B., M.B., A.P., B.B., C.S., M.C., P.R.G., M.A., and P.S. submitted and interpreted data, and commented on the manuscript. D.J. interpreted data and commented on the manuscript.

A complete list of the participating study groups can be found in Document S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Heinz Ludwig, Department of Medicine, Wilhelminenspital, Montleartstr. 37, 1160 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: heinz.ludwig@wienkav.at.

References

- 1.Wisloff F, Andersen P, Andersson TR, et al. Has the incidence of multiple myeloma in old age been underestimated? The Myeloma project of health region I in Norway. Euro J Haematol. 1991;47:33–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1991.tb01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergsagel D. The incidence and epidemiology of plasma cell neoplasms. Stem Cells. 1995;13:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corso A, Klersy C, Lazzarino M, Bernasconi C. Multiple myeloma in younger patients:the role of age as prognostic factor. Ann Haematol. 1998;76:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s002770050365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blade J, Kyle RA, Greipp PR. Presenting features and prognosis in 72 patients with multiple myeloma who were younger than 40 years. Br J Haematol. 1996;93:345–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.5191061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacher U, Kern W, Schnittger S, Hiddemann W, Haferlach T, Schoch C. Population-based age-specific incidences of cytogenetic subgroups of acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2005;90:1502–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gajdos C, Tartter PI, Bleiweiss IJ, Bodian C, Brower ST. Stage 0 to stage III breast cancer in young women. Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:523–529. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, et al. International Staging System for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3412–3420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durie BGM, Salmon S. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingston; 1977. Recent advances in Haematology. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickman P, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med. 2004;23:51–64. doi: 10.1002/sim.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.University of California, Berkeley (CA), Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Berlin, Germany) Human Mortality Database. [Accessed March 31, 2006]. Available at: www.mortality.org.

- 11.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blade J, Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma in young patients: clinical presentation and treatment approach. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;30:493–501. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenhoff S, Hjorth M, Westin J, et al. Impact of age on survival after intensive therapy for multiple myeloma: a population-based study by the Nordic Myeloma Study Group. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reece DE, Bredeson C, Perez WS, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients < 60 versus ≥ 60 years of age. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:1135–1143. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegel DS, Desikan KR, Mehta J, et al. Age is not a prognostic variable with autotransplants for multiple myeloma. Blood. 1999;93:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Dickman PW, et al. , Patterns of survival in multiple myeloma: a population-based study of patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2007;20:1993–1999. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Recent major improvement in long-term survival of younger patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104984. Prepublished September 27, 2007, as DOI 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blade J, Kyle RA, Greipp PR. Multiple myeloma in patients younger than 30 years: report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1463–1468. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440120125014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dingli D, Timm M, Russell SJ, Witzig TE, Raijkumar SV. Promising preclinical activity of 2-methoxyestradiol in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3948–3954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger U, Maywald O, Pfirrmann M, et al. German CML-Study Group. Gender aspects in chronic myeloid leukemia: long-term results from randomized studies. Leukemia. 2005;19:984–989. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett JM, Young ML, Andersen JW, et al. Long-term survival in acute myeloid leukemia: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Cancer. 1997;80:2205–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson T, Lenhoff S, Turesson I, et al. Cytogenetic features of multiple myeloma: impact of gender, age, disease phase, culture time, and cytokine stimulation. Eur J Haematol. 2002;68:345–353. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sagaster V, Kaufmann H, Odelga V, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities of young multiple myeloma patients (< 45 years) are not different from those of other age groups and are independent of stage according to the International Staging System. Eur J Haematol. 2007;78:227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2006.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross FM, Ibrahim AH, Vilain-Holmes A, et al. UK Myeloma Forum. Age has a profound effect on the incidence and significance of chromosome abnormalities in myeloma. Leukemia. 2005;19:1634–1642. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludwig H, Fritz E, Friedl HP. Epidemiologic and age-dependent data on multiple myeloma in Austria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1982;68:729–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:21–33. doi: 10.4065/78.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2002, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda MD. [Accessed January 17, 2007]. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/results_single/sect_01_table.11_2pgs.pdf.

- 30.Krejci M, Buchler T, Hajek R, et al. Prognostic factors for survival after autologous transplantation: a single centre experience in 133 multiple myeloma patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:159–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavo M, Galieni P, Zuffa E, et al. Prognostic variables and clinical staging in multiple myeloma. Blood. 1989;74:1774–1780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma: a review of 869 cases. Proc Mayo Clinic. 1975;50:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]