Abstract

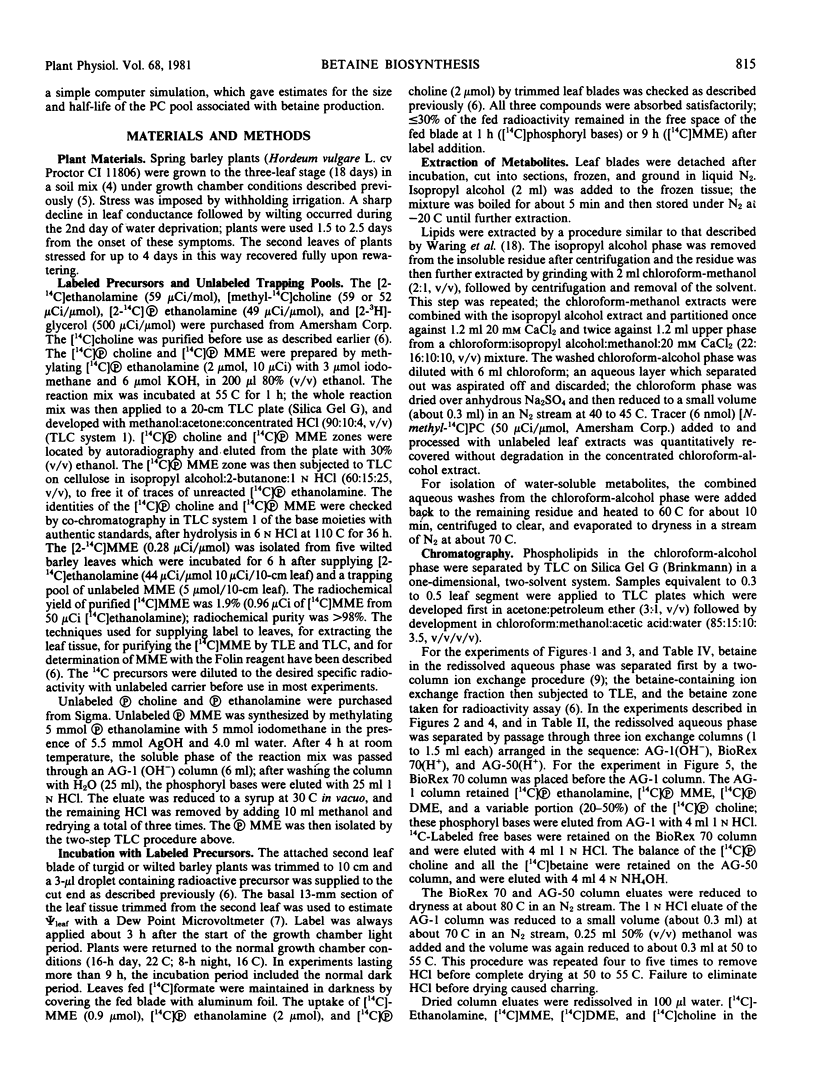

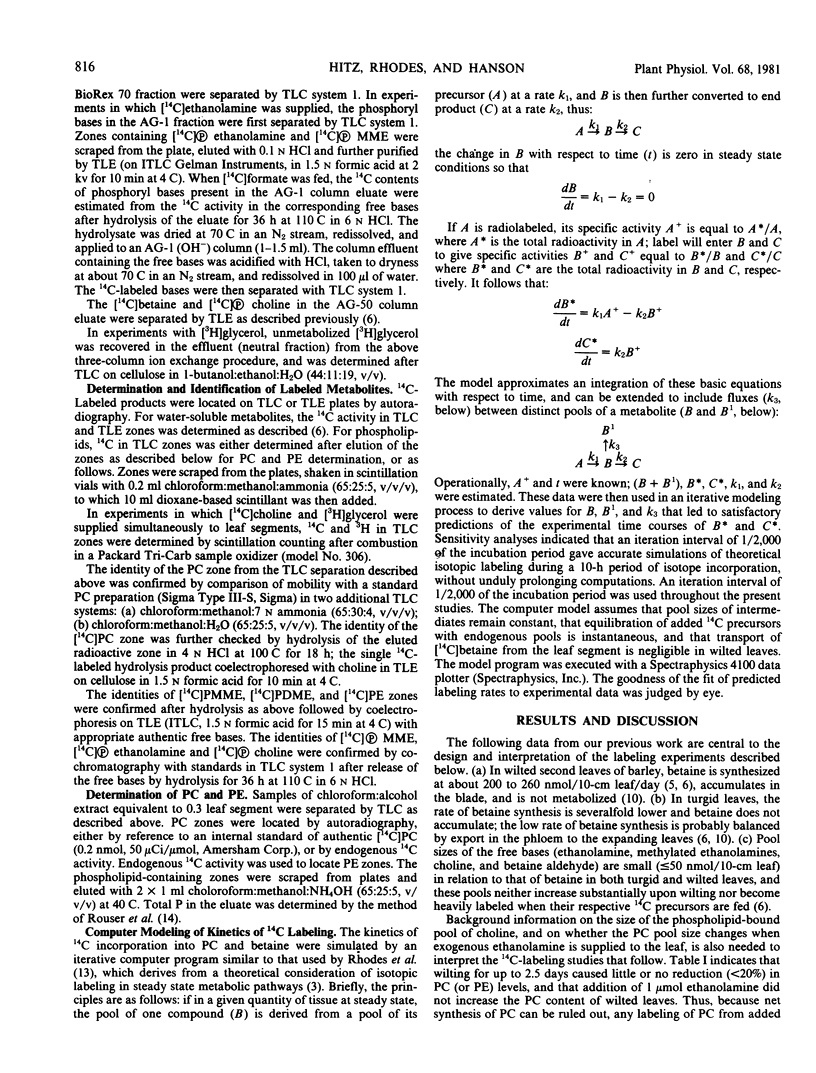

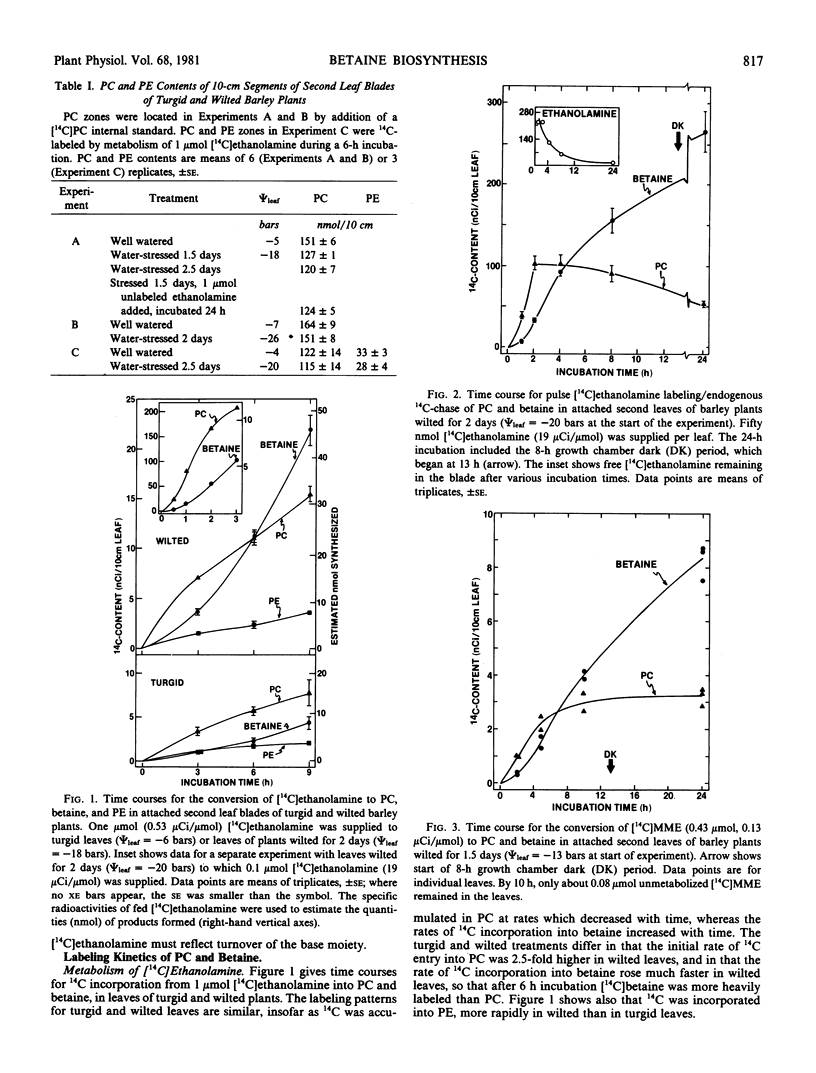

In barley, glycine betaine is a metabolic end product accumulated by wilted leaves; betaine accumulation involves acceleration of de novo synthesis from serine, via ethanolamine, N-methylethanolamines, choline, and betaine aldehyde (Hanson, Scott 1980 Plant Physiol 66: 342-348). Because in animals and microorganisms the N-methylation of ethanolamine involves phosphatide intermediates, and because in barley, wilting markedly increases the rate of methylation of ethanolamine to choline, the labeling of phosphatides was followed after supplying [14C]ethanolamine to attached leaf blades of turgid and wilted barley plants. The kinetics of labeling of phosphatidylcholine and betaine showed that phosphatidylcholine became labeled 2.5-fold faster in wilted than in turgid leaves, and that after short incubations, phosphatidylcholine was always more heavily labeled than betaine. In pulse-chase experiments with wilted leaves, label from [14C]ethanolamine continued to accumulate in betaine as it was being lost from phosphatidylcholine. When [14C]monomethylethanolamine was supplied to wilted leaves, phosphatidylcholine was initially more heavily labeled than betaine. These results are qualitatively consistent with a precursor-to-product relationship between phosphatidylcholine and betaine.

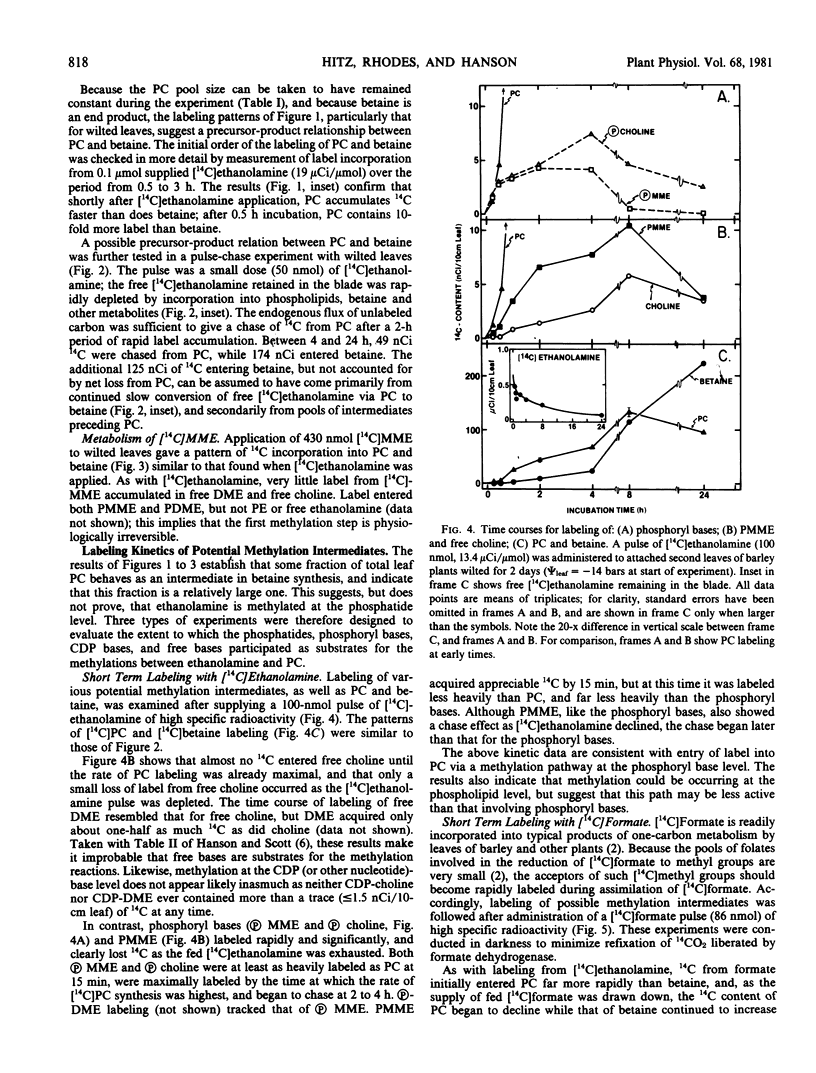

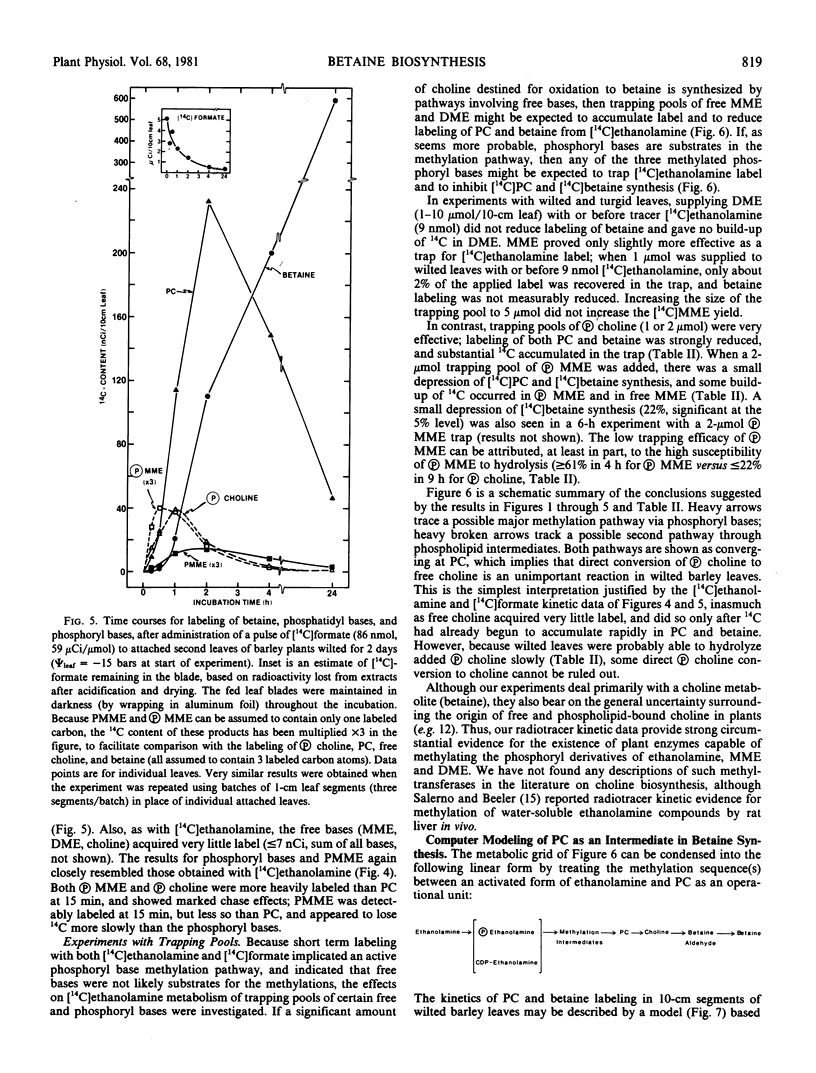

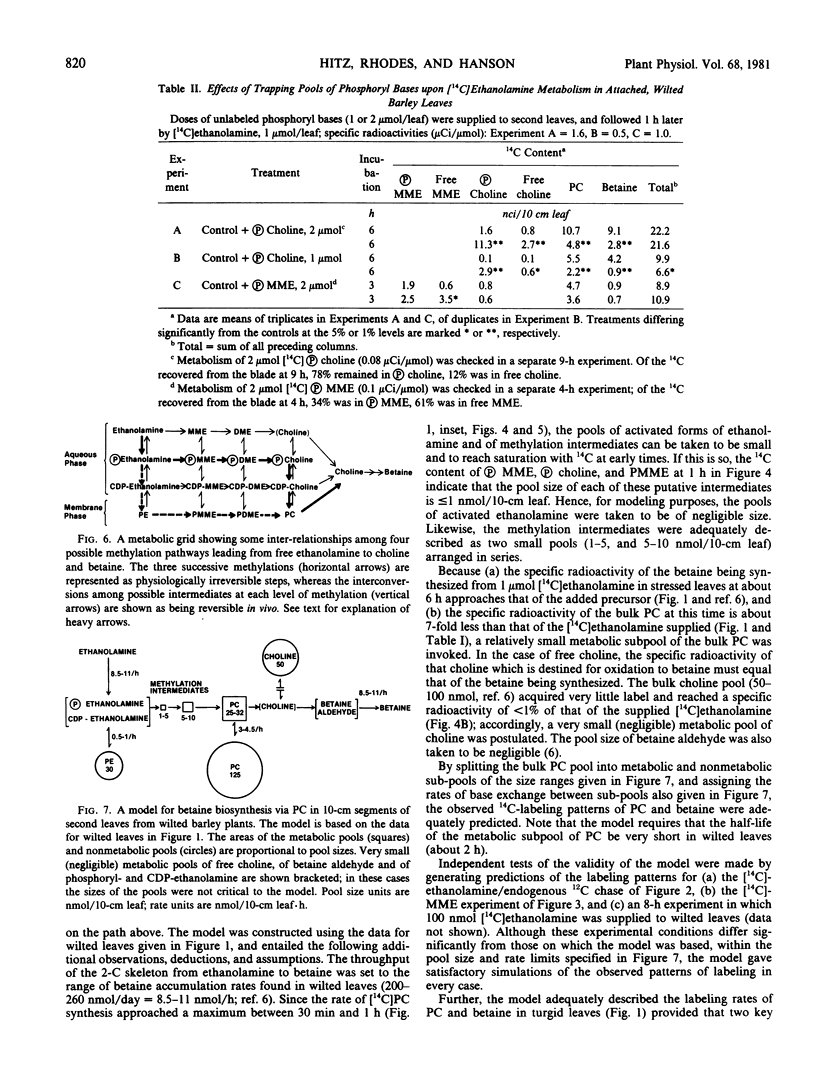

The following experiments, in which tracer amounts of [14C]ethanolamine or [14C]formate were supplied to wilted barley leaves, implicated phosphoryl and phosphatidyl bases as intermediates in the methylation steps between ethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine. Label from both [14C]ethanolamine and [14C]formate entered phosphorylmonomethylethanolamine and phosphorylcholine very rapidly; these phosphoryl bases were the most heavily labeled products at 15 to 30 minutes after label addition and lost label rapidly as the fed 14C-labeled precursor was depleted. Phosphatidylmonomethylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine were also significantly labeled from [14C]ethanolamine and [14C]formate at early times; the corresponding free bases and nucleotide bases were not. Addition of a trapping pool of phosphorylcholine reduced [14C]ethanolamine conversion to both phosphatidylcholine and betaine, and resulted in accumulation of label in the trap.

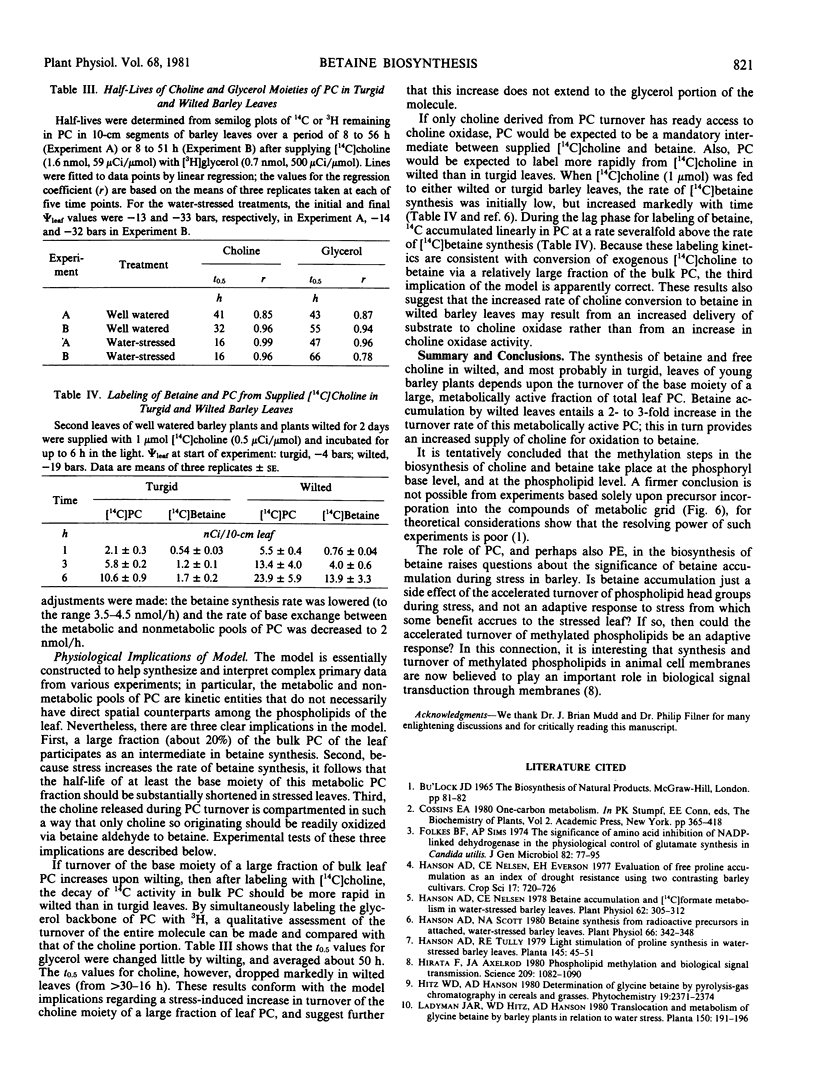

A computer model of the synthesis of betaine via phosphatidylcholine was developed from 14C kinetic data. The model indicates that about 20% of the total leaf phosphatidylcholine behaves as an intermediate in betaine biosynthesis and that a marked decrease (≥2-fold) in the half-life of this metabolically active phosphatidylcholine fraction accompanies wilting. Dual labeling experiments with [14C]choline and [3H]glycerol confirmed that the half-life of the choline portion of phosphatidylcholine falls by a factor of about 2 in wilted leaves.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Folkes B. F., Sims A. P. The significance of amino acid inhibition of NADP-linked glutamate dehydrogenase in the physiological control of glutamate synthesis in Candida utilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1974 May;82(1):77–95. doi: 10.1099/00221287-82-1-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson A. D., Nelsen C. E. Betaine Accumulation and [C]Formate Metabolism in Water-stressed Barley Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1978 Aug;62(2):305–312. doi: 10.1104/pp.62.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson A. D., Scott N. A. Betaine Synthesis from Radioactive Precursors in Attached, Water-stressed Barley Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1980 Aug;66(2):342–348. doi: 10.1104/pp.66.2.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata F., Axelrod J. Phospholipid methylation and biological signal transmission. Science. 1980 Sep 5;209(4461):1082–1090. doi: 10.1126/science.6157192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M. O., Kates M. Biosynthesis of nitrogenous phospholipids in spinach leaves. Can J Biochem. 1974 Jun;52(6):469–482. doi: 10.1139/o74-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T. S. Phosphatidylcholine synthesis in castor bean endosperm. Plant Physiol. 1976 Mar;57(3):382–386. doi: 10.1104/pp.57.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouser G., Fkeischer S., Yamamoto A. Two dimensional then layer chromatographic separation of polar lipids and determination of phospholipids by phosphorus analysis of spots. Lipids. 1970 May;5(5):494–496. doi: 10.1007/BF02531316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno D. M., Beeler D. A. The biosynthesis of phospholipids and their precursors in rat liver involving de novo methylation, and base-exchange pathways, in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Dec 20;326(3):325–338. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(73)90134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring A. J., Breidenbach R. W., Lyons J. M. In vivo modification of plant membrane phospholipid composition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976 Aug 16;443(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90499-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch H. Phosphoglyceride metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1974;43(0):243–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.43.070174.001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]