Abstract

Mesoaxial synostotic syndactyly, Malik-Percin type (MSSD) (syndactyly type IX) is a rare autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic digit anomaly with only two affected families reported so far. We previously showed that the trait is genetically distinct from other syndactyly types, and through autozygosity mapping we had identified a locus on chromosome 17p13.3 for this unique limb malformation. Here, we extend the number of independent pedigrees from various geographic regions segregating MSSD to a total of six. We demonstrate that three neighboring missense mutations affecting the highly conserved DNA-binding region of the basic helix-loop-helix A9 transcription factor (BHLHA9) are associated with this phenotype. Recombinant BHLHA9 generated by transient gene expression is shown to be located in the cytoplasm and the cell nucleus. Transcription factors 3, 4, and 12, members of the E protein (class I) family of helix-loop-helix transcription factors, are highlighted in yeast two-hybrid analysis as potential dimerization partners for BHLHA9. In the presence of BHLHA9, the potential of these three proteins to activate expression of an E-box-regulated target gene is reduced considerably. BHLHA9 harboring one of the three substitutions detected in MSSD-affected individuals eliminates entirely the transcription activation by these class I bHLH proteins. We conclude that by dimerizing with other bHLH protein monomers, BHLHA9 could fine tune the expression of regulatory factors governing determination of central limb mesenchyme cells, a function made impossible by altering critical amino acids in the DNA binding domain. These findings identify BHLHA9 as an essential player in the regulatory network governing limb morphogenesis in humans.

Introduction

Mesoaxial synostotic syndactyly, Malik-Percin type (MSSD [MIM 609432]) (syndactyly type IX) demonstrates a distinctive combination of clinical features that include mesoaxial osseous synostosis at metacarpal level, reduction of one or more phalanges, hypoplasia of distal phalanges of preaxial and postaxial digits, clinodactyly of fifth fingers, and preaxial fusion of toes.1 Only two families with this autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic digit anomaly have been reported so far.1–3 Of the nine well-characterized nonsyndromic syndactylies, it is the only recessive type beyond syndactyly type VII, Cenani-Lenz syndactyly (CLS [MIM 212780]).4,5

Through autozygosity mapping we had identified a locus on chromosome 17p13.3 for this unique limb malformation.2 The same chromosomal region harbors a locus for autosomal-dominant split-hand/foot malformation and long bone deficiency of variable expression and incomplete penetrance (SHFLD [MIM 612576]),6,7 which has recently been shown to be associated with 17p13.3 duplications with a small region of overlap encompassing only a gene coding for the basic helix-loop-helix A9 transcription factor (BHLHA9 [MIM 615416]).8–11 BHLHA9 had been predicted to contain a single exon coding for a class II basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor.12 It emerges as a candidate gene also for MSSD because it is specifically expressed in the distal mesenchyme of E10.5–E11.5 mouse embryo limb buds, when patterning of digital rays of the autopods is taking place, and homozygous bhlha9 knockout mice displayed various degrees of simple incomplete webbing of forelimb digits 2–3 involving soft tissue, but not skeletal elements.11,13,14 In addition, in mild cases, hand malformations associated with 7p13.3 duplications resemble MSSD.6,10

To identify the gene mutations that cause MSSD, we recruited additional families from various geographic regions segregating the trait. Coding exon sequencing of candidate genes from the region defined by genetic mapping in a total of six pedigrees detected missense mutations that were associated with this phenotype affecting the highly conserved DNA-binding region of BHLHA9. Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins are transcription factors involved in the regulation of embryonic development. They share a basic domain that binds to regulatory E-box DNA and a helix-loop-helix domain that facilitates homo- or heterodimerization of HLH protein monomers.15 To support the notion that missense mutations of BHLHA9 cause MSSD, we set out to examine functional properties of the protein such as intracellular localization, to search experimentally for potential dimerization partners, and to compare the impact of wild-type versus mutant BHLHA9 protein on target gene transcription. BHLHA9 abridged the activating potential of widely expressed E-box proteins considerably. Because it can likewise bind other cell-type-specific bHLH proteins, it might sequester them, thus indirectly influencing gene expression control. Exchanging critical amino acids in the DNA binding domain of BHLHA9 destroys these capabilities to fine tune control of regulatory pathways specifically during limb development.

Subjects, Material, and Methods

Subjects and Families

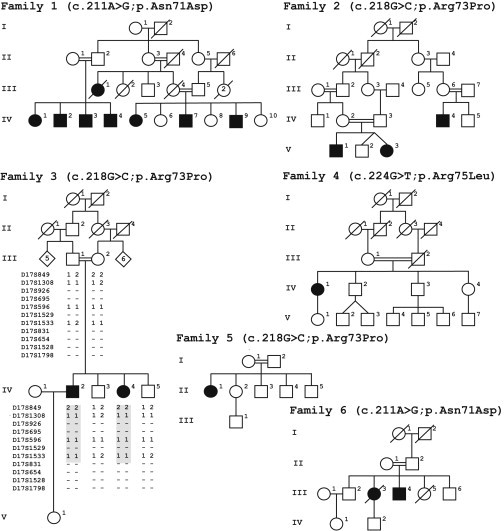

This study included six multigenerational pedigrees from Turkey, Pakistan, and Italy (Figure 1). The design of the study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocols. Peripheral blood samples were collected after informed consent from individuals listed in Table 1, according to protocols approved by the participating institutions. Examination of medical records and mutation analysis procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the respective national and institutional committees on human subject research.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees Harboring Subjects with the Autosomal-Recessive Phenotype Syndactyly Type IX, Mesoaxial Synostotic Syndactyly, Malik-Percin Type

For clarity, pedigrees have been trimmed. Extended pedigrees for families 1 and 2 have been reported previously.1,3 Black symbols indicate clinically affected individuals. Haplotypes for the microsatellite markers from the candidate interval at chromosome 17p13.3 genotyped in family 3 are depicted. The autozygous region segregating in the affected subjects is given in shaded block. A minus sign (−) shows the alleles that could not be genotyped. BHLHA9 missense mutations segregating in the families are indicated.

Table 1.

Probands, Phenotypes, and Genotypes in Six MSSD-Affected Families

|

Families |

Phenotypes |

BHLHA9 Genotypes |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family, Origin | Affected Subjects | Subject | Affection Status | Mesoaxial Reduction of Finger | Short Index Finger | Clinodactyly | Preaxial Toes Webbing | Mesoaxial (2/3 Toes) Webbing | Alleles BHLHA9 c.211 | Alleles BHLHA9 c.218 | Alleles BHLHA9 c.224 |

| Fam1, Pakistan, Punjab | 5M, 3F | IV-7 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | GG | GG | GG |

| IV-5 | A | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | – | GG | GG | GG | ||

| IV-1 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | – | GG | GG | GG | ||

| IV-2 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | GG | GG | GG | ||

| II-1 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AG | GG | GG | ||

| II-2 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AG | GG | GG | ||

| II-5 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AG | GG | GG | ||

| III-5 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AG | GG | GG | ||

| IV-10 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AG | GG | GG | ||

| Fam2, Turkey | 2M, 1F | IV-3 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG |

| IV-2 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG | ||

| V-3 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | AA | CC | GG | ||

| V-2 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | GG | GG | ||

| V-1 | A | ++ | ++ | – | ++ | – | AA | CC | GG | ||

| III-6 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG | ||

| IV-4 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | AA | CC | GG | ||

| III-7 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG | ||

| Fam3, Turkey | 1M, 1F | III-1 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG |

| III-2 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG | ||

| IV-2 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | AA | CC | GG | ||

| IV-3 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | GG | GG | ||

| IV-4 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | + | AA | CC | GG | ||

| IV-5 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG | ||

| Fam4, Italy, central | 1F | IV-1 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | + | AA | GG | TT |

| III-1 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | GG | TG | ||

| V-1 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | GG | TG | ||

| Fam5, Pakistan, Sindh | 1F | I-2 | N | – | – | – | – | – | AA | CG | GG |

| II-1 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | – | AA | CC | GG | ||

| Fam6, Pakistan, KPK | 1M, 1F | III-4 | A | ++ | ++ | ++ | – | ++ | GG | GG | GG |

Abbreviations are as follows: A, affected; N, not affected; M, male; F, female; ++, bilateral; +, unilateral.

Control DNA samples were taken from 79 individuals from Europe and from 61 probands from Pakistan, unrelated to the families under study. Families 1 and 2 have been reported previously.2 Families originating from Turkey or Pakistan (Table 1) are, reportedly, geographically distinct and unrelated. The number of affected subjects in the reported families varied from eight to one. We observed a total of 17 affected individuals (9 male, 8 female). Parental consanguinity was reported, in line with autosomal-recessive inheritance pattern.

Genetic Mapping

In order to check for the cosegregation of the type IX syndactyly locus (chromosome 17p13.3) with the phenotypes segregating in family 3, we genotyped highly informative microsatellite markers from the candidate interval (Table S1 available online). Procedures for genomic DNA preparation, PCR amplification, allele separation and calling, and linkage analysis were essentially the same as described previously.1,2

Haplotype Analysis

To obtain an indication for potential founder mutations, haplotypes of a selection of 45 common SNPs listed in dbSNP build 138 in a 10.7 kb segment of chromosome 17p13.3 (Table S2), encasing BHLHA9, were genotyped by DNA sequence analysis in affected individuals from Turkey and Pakistan carrying identical BHLHA9 mutations.

Mutation Analysis of Candidate Genes

To screen candidate genes from the defined interval for pathogenic mutation(s), the coding sequences of FAM57A (RefSeq accession number NM_024792.1; MIM 611627), TUSC5 (RefSeq NM_172367.2; MIM 612211), INPP5K (RefSeq NM_130766.2; MIM 607875) (primer sequences available on request), and BHLHA9 (RefSeq NM_001164405.1) were PCR amplified. DNA sequencing was performed on both strands by Sanger sequencing. Trace chromatogram data were analyzed by Sequencher 4.7 software (Gene Codes Corp.). Primer pairs and PCR conditions for the amplification of the single coding exon of BHLHA9 and for sequence analysis of the PCR products on both strands are listed in Table S3. Mutations in the coding region of BHLHA9 were confirmed by independent methods such as an amplification refractory mutation system (c.218G>C [p.Arg73Pro]; families 2, 3, 5; primers in Table S3) and mutation-specific restriction enzyme digestion (c.211A>G [p.Asn71Asp]; families 1 and 6; with restriction enzyme AjiI; c.224G>T [p.Arg75Leu], family 4, with restriction enzyme SacI). To exclude that the variants represented SNPs, DNA samples from unaffected family members, 79 unrelated control individuals of self-reported European ancestry, and 61 control individuals from Pakistan were scrutinized by the same procedures, and the sequence of the mutated alleles was searched in public databases (dbSNP, HapMap, 1000 Genomes, Exome Variant Server).

Molecular Constructs

The translated segment of Homo sapiens (Hs) basic helix-loop-helix family member A9 cDNA (BHLHA9) in pCMV6-Entry (C-terminal Myc and DDK tagged) (pCMV6_HsBHLHA9/wt) and pCMV6-Entry (C-terminal Myc and DDK tagged) were obtained from OriGene The translated segments of mutant HsBHLHA9 cDNA (BHLHA9/N71D, BHLHA9/R73P, BHLHA9/R75L) were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of individuals carrying these mutations (via primers BH_SgfI for, BH_MluI rev; Table S3) and cloned into the SgfI and MluI sites of pCMV6-Entry to generate pCMV6_HsBHLHA9/N71D, pCMV6_HsBHLHA9/R73P, and pCMV6_HsBHLHA9/R75L.

The translated segments of human TCF3 (RefSeq NM_001136139.2; MIM 147141), TCF4 (RefSeq NM_001083962.1; MIM 602272), and TCF12 (RefSeq NM_003205.3; MIM 600480) were isolated by PCR (Table S3) from the potentially complete cDNA clones (BC110580.1/IRCMp5012E0634D, BC125084.1/IRCMp5012C034D, and BC050556/IRATp970B1176D, Source Bioscience) and inserted by TOPO cloning into pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen). The inserts of the resulting constructs were shuttled via Gateway (gw) technology (Invitrogen) into pcDNA6.2/N-YFP-DEST (Invitrogen) to generate pcDNA6.2/N-YFP-DEST_HsTCF3, pcDNA6.2/N-YFP-DEST_HsTCF4, and pcDNA6.2/N-YFP-DEST_HsTCF12. pCMV6-AC-GFP and HsTCF4 in pCMV6-AC-GFP were obtained from OriGene.

Human TWIST1 and HAND2 cDNAs (BC036704.2; MIM 601622 and BC101406.1; MIM 602407, respectively) in plasmids pCMV6_HsTWIST1 and pCMV6_HsHAND2 were obtained from OriGene.

Reporter plasmid 8xEbox-mE5 based on the pGL3 luciferase vector (Promega) driven by an 8xEbox-mE5 element upstream of a fos promoter was kindly provided by M. Sigvardsson, Linköping.16 From this vector, the 8xEbox-mE5 element was isolated by PCR (Table S3) and subsequent HindIII/KpnI digestion, and recloned into pGL4.23[luc2/minP] (Promega) upstream of a minimal promoter. The control luciferase plasmid pGL4.74[hRLuc/TK] encoding a Renilla-luciferase gene driven constitutively by a thymidine kinase (TK) promoter was also obtained from Promega. The structures and insert sequences of all plasmids were verified by sequencing (Table S3).

Histochemical Analysis of Transiently Transfected Cells

Cos7 cells were maintained under standard conditions in DMEM_10% (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium containing GlutaMax [Invitrogen], nonessential amino acids, penicillin, streptomycin, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum). A total of 2 × 105 cells each were seeded in 2 ml of this medium per well of two-well Lab-Tek chamber slides. After 24 hr, for each of the wells, transfection complexes composed of 3 ml Attractene (QIAGEN) and 500 ng DNA of recombinant constructs expressing human wild-type or mutant HsBHLHA9_MYC/DDK and/or HsTCF4_GFP fusion proteins were mixed in 120 μl DMEM without serum, incubated for 20 min at room temperature to allow formation of transfection complexes, and subsequently added drop wise to the cells in 2 ml fresh DMEM_10%. The cells with the transfection complexes were incubated under normal growth conditions. After 24 hr, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM_10%, and incubation was continued for 24 hr. After methanol/acetone fixation of the cells, MYC-tagged BHLHA9 was immunostained with anti-c-myc mouse IgG monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes: A21270, 1:100) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes: A11005) as secondary antibody (1:200). Intracellular localization of HsTCF4 could be detected by fluorescence of the GFP tag. Immunostained cells were washed thoroughly with PBS/0.5% Tween 20 and mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI for staining of nuclei (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes). Images were taken on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH) with a Leica DFC 300 FX camera (Leica Microsystems) and processed with the Leica imaging system 50 (IM50) software.

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assays

The efficiency of enhancing transient expression in Cos7 or in osteosarcoma-derived U2OS cells of an 8xEbox-enhanced fos-promoter driven pGL3 Firefly luciferase reporter gene16 or an 8xEbox-enhanced minimal-promoter driven pGL4.23[luc2/minP] Firefly luciferase reporter gene was tested for HsBHLHA9 wild-type or mutant proteins alone or in combination with potentially interacting human bHLH-proteins TCF3, TCF4, TCF12, TWIST1, or HAND2. A total of 1.5 × 105 Cos7 cells or 2 × 105 U2OS cells per well were set up in triplicate in 12-well plates in 2 ml DMEM_10% and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. After 24 hr, fresh medium was added, and the cells were transfected by adding to each well a mixture containing 200 μl serum-free DMEM, 3 μl TurboFect in vitro transfection reagent (Thermo Scientific), 500 ng each of pGL3 or pGL4.23 Firefly luciferase reporter gene constructs with or without 8xEbox-enhancer, 500 ng of an expression plasmid (pCMV6-Entry_Myc/DDK) with or without BHLHA9 cDNA insert, 500 ng each of an expression plasmid (pcDNA6.2/N-YFP-DEST) with or without human TCF3, TCF4, TCF12, TWIST1, or HAND2 cDNA insert, and 50 ng of pGL4.74 Renilla luciferase expression plasmid as control for transfection efficiency. After 8 hr at 37°C, 5% CO2, incubation was continued in fresh DMEM_10% for 16 hr. After washing the cells twice with PBS, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for Firefly- and Renilla-luciferase activities in a luminometer Auto Lumat LB953 (Berthold Technologies) with a dual luciferase reporter assay system as suggested by the supplier (Promega). These triplicate experiments were performed three times.

Results

Clinical Findings in MSSD-Affected Families

Clinical descriptions of families 1 and 2 have been reported.1–3

Two children in a Turkish sibship of four (family 3) were affected with Malik-Percin syndactyly. The unaffected parents were first cousins, suggesting an autosomal-recessive inheritance (Figure 1, Table 1). The affected subjects each had four fingers bilaterally. Their short index fingers showed radial diversion, the third and fourth fingers were replaced by a single thick digit, and the fifth fingers showed clinodactyly (Figures 2A and 2C). In the feet there was partial cutaneous webbing of toes 1–4 (Figures 2B and 2I).

Figure 2.

MSSD Phenotype of Affected Subjects

(A and B) Hands (A) and left foot (B) of subject IV-2 from family 3.

(C and I) Hands (C) and feet (I) of subject IV-4 from family 3.

(D–F) Hands (D), left foot (E), and radiogram (F) of subject IV-1 from family 4.

(G and H) Hands (G) and feet (H) of subject III-4 from family 6.

Pedigrees and phenotypes are presented in Figure 1 and Table 1.

A 50-year-old woman from Central Italy was admitted to the Hand Surgery Clinic of the University Hospital of Modena for chronic pain and severe functional limitation of the thumbs due to bilateral rhizarthrosis of the trapezio-metacarpal joint. She presented a congenital bilateral syndactyly of the third and fourth fingers of both hands with a synostosis of the corresponding metacarpals, a mild phalangeal shortening (from the proximal to the distal) involving all the fingers including the thumb, and a fifth finger clinodactyly (Figures 1D–1F). A bilateral syndactyly of the second and third toes was also present. The analysis of the pedigree excluded the presence of hand malformations in the relatives and revealed consanguinity; the parents of the proband were first cousins (Figure 1, Table 1, family 4). The most affected thumb, the right, was surgically treated by arthrodesis of the trapezio-metacarpal joint with a scarce relief of the symptoms.

Family 5 originates from South Pakistan (Sindh). The only subject affected with MSSD was a 24-year-old female with consanguineous parents (Figure 1, Table 1). She presented with no developmental malformation other than at the hands. The feet were unaffected. In the family, no previous history of any limb defect was reported. She had four digits in both hands; the mesoaxial digits were missing bilaterally. The fingers were relatively short, hypoplastic, and gave an impression of radial deviation. The fifth fingers were showing clinodactyly, more pronounced in the left hand. Finger tips were tapering with hypoplastic nail plates. In the second and fourth digits, the nails were reduced to small islands, but the nail plates of the first and last digits were less affected.

In family 6 from the KPK province of Pakistan, there were two affected subjects (one male, one female), of which one was deceased (Figure 1). The only affected subject available for analysis in this kindred was a 23-year-old male (III-4). He was third in the sibship of five, and his parents were first cousins once removed. There was no family history of limb or any other malformation. The index subject was observed to have four digits in both hands, and one of the mesoaxial digits was omitted, bilaterally (Figure 2G). The thumbs were short, and the index fingers depicted valgus deviations at their terminal phalanx. Additionally, the left index finger had symphalangism. The third and fourth fingers were replaced by single digit, which demonstrated broad proximal phalanx, hypoplastic and club-shaped terminal phalanx, and reduced nail, bilaterally. The fifth fingers were dysplastic and exhibited clinodactyly. At the palmar side, characteristic dermatoglyphic changes were evident, i.e., triradii were grossly distorted and interdigital flexion creases were less remarkable. The phenotype in the feet was characterized by hallux varus, partial zygodactyly between second and third toes, and shortening of fourth toes, bilaterally (Figure 2H). The nails of digits 2–4 were hypoplastic.

The trait appeared to be inherited as autosomal recessive without sex bias. The affected subjects in all six families had remarkable similarities in their limb phenotypes. Generally, the phenotype in hands was bilateral and symmetrical but was unilateral and asymmetrical in feet. Roentgenographic examination depicted synostosis of third and fourth metacarpals, resulting in a single, broad, and conical proximal phalanx, ending in dysplastic middle and terminal phalanx. In fifth fingers, there was bilateral clinodactyly along with symphalangism at middle-distal phalanx. Distal heads of metacarpals generally showed hypoplasia. There was crowding of carpal bones (Figure 2F). In the feet there was no evidence of bony involvement. However, hypoplasia of middle and distal phalanx of all toes was frequently observed.

Genetic Mapping Confirms Candidate Region

Genotyping in family 3 (Figure 1) revealed homozygosity in both affected subjects IV-2 and IV-4 from microsatellite markers D17S849 to D17S1533, whereas two unaffected subjects (IV-3 and IV-5) and the parents (III-1 and III-2) were heterozygous (Figure 1). Joining of data of this family and the two families previously reported2 slightly improved the LOD scores in the critical interval on chromosome 17p13.3. Highest pair-wise scores were established with microsatellites D17S1533, D17S695, and D17S926, respectively, at Θ = 0.0 (Table S1).

Detection of Functionally Detrimental Mutants Suggests that BHLHA9 Is Altered in MSSD

Out of 19 RefSeq genes predicted in the candidate interval, four candidate genes coding for potentially regulatory proteins were chosen for mutation analysis by sequencing DNA of affected individuals. No potentially pathogenic change was observed in the coding regions of FAM57A, TUSC5, and INPP5K. However, mutation analysis in BHLHA9, coding for a bHLH protein, revealed three different sequence variants homozygous only in affected subjects (9 males, 8 females) and heterozygous in the unaffected parents (c.211A>G [p.Asn71Asp], families 1 and 6; c.218G>C [p.Arg73Pro], families 2, 3, 5; c.224G>T [p.Arg75Leu], family 4). None of the unaffected sibs was homozygous for these mutations, suggesting complete penetrance (Figure 1, Table 1, Figure S1). The mutations were confirmed by independent methods (Figure S2). These sequence variants were not observed in 280 chromosomes analyzed from a panel of healthy European and Asian individuals. Likewise, they are not listed in SNP databases (dbSNP, 1000 Genomes, HapMap, Exome Variant Server).

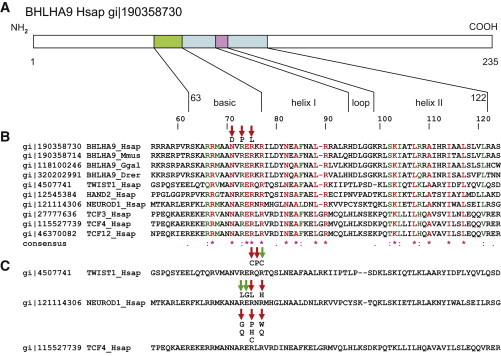

The putative only coding exon of BHLHA9 determines a highly conserved basic helix-loop-helix protein. The three mutations observed in the MSSD-affected families are positioned in close proximity and exchange critical, conserved amino acids of the DNA-binding region of the basic domain (Figure 3). Prediction programs classify all three variants to be probably damaging (Table S4).

Figure 3.

Mutations Affecting DNA Binding Sites of Human BHLHA9 and Homologous bHLH Proteins

(A) Model of human BHLHA9 with depiction of the basic helix-loop-helix region as indicated in the NCBI Protein database.

(B) Mapping of MSSD-associated missense mutations to the basic nucleic acid binding site of BHLHA9 enclosing the E-box specificity site identified with the CCD program,35 projected onto an amino acid sequence alignment of orthologous BHLHA9 sequences from various vertebrates and of human (Hsap) TCF3, TCF4, TCF12, TWIST1, HAND2, and NEUROD1 sequences generated by ClustalW.36 Numbering of amino acids refers to human (Hsap) BHLHA9. NCBI sequence identifiers (gi) are indicated. The amino acids mutated in the MSSD-affected individuals (red arrows) are conserved in all aligned proteins. Species abbreviations are as follows: Mmus, Mus musculus; Ggal, Gallus gallus; Drer, Danio rerio.

(C) Amino acid substitutions in the DNA-binding region of the basic domain of helix 1 associated with somatic mutations in cancer listed in the COSM database (green arrows) and/or clinical Mendelian phenotypes (red arrows).

TWIST1: p.Arg118Cys, in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome (SCS)23 and COSM1449859; p.Gln119Pro, SNP rs104894057, in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome;23,24 p.Arg120Cys in COSM1269548.

NEUROD1: p.Arg109Leu in COSM719047; p.Glu119Gly in COSM402132; p.Arg111Leu, rs104893649, in diabetes mellitus type II (NIDDM); p.Arg113His in COSM1217138.

TCF4: p.Arg576Gly, p.Arg576Gln, p.Arg578Pro, p.Arg578His, p.Arg580Trp, p.Arg580Gln in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (PTHS), references in Sepp et al.;37 p.Arg578Cys in COSM563719 and COSM1141464.

The association of detrimental missense mutations affecting homologous amino acids in the basic DNA-binding region of these bHLH proteins with clinical phenotypes adds weight to the notion that the comparable mutations in BHLHA9 cause MSSD.

Affected Individuals from Families Carrying an Identical Mutation Share 17p13.3 Haplotypes

Genotypes of 45 common SNPs in a 10.7 kb segment of chromosome 17p13.3, encasing BHLHA9, each were identical in affected individuals of families 1 and 6 (c.211A>G [p.Asn71Asp]) from Pakistan and families 2 and 3 (c.218G>C [p.Arg73Pro]) from Turkey, respectively (Table S2). Different alleles were detected in the haplotype of an affected person with the mutation c.218G>C (p.Arg73Pro) in family 5 from Pakistan.

BHLHA9 Can Bind TCFs, HAND2, and TWIST1

In Y2H screens of d11 and d17 mouse embryo libraries, three quarters of the interactions with a BHLHA9 bait were detected with TCF3, TCF4, and TCF12 (Table S5). Other preys were detected only once or were considered false-positive hits (data not shown). The dimerization of human TCF proteins with HsBHLHA9 was confirmed by one-to-one Y2H (Figure S4). Likewise, one-to-one Y2H analyses showed that HsBHLHA9 can bind human HAND2 and TWIST1 (Figure S4). Strongest interactions, as determined by growth at stringency of 25 mM 3at, were observed with HsTCF12.

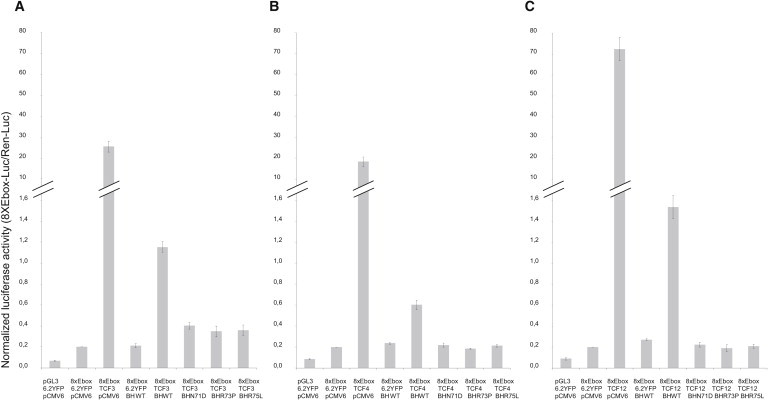

BHLHA9 Tunes the Activation Potential of E-box Protein Transcription Factors

Myc-tagged BHLHA9 produced by transient gene expression in Cos7 cells was localized both in the cytoplasm and in the cell nucleus. This localization was not affected by any of the mutations observed in MSSD-affected individuals. In contrast, YFP-tagged TCF4 was detected only in the cell nucleus (Figure S3). In Cos7 cells, expression of a human BHLHA9 transgene alone was insufficient to activate above control the expression of luciferase reporter constructs enhanced by E-box sequences upstream of fos- or minimal promoters (Figure 4). In contrast, human TCF3, TCF4, and TCF12 acted as strong activators. This activation was reduced 20–40 times, when the cDNAs coding for these class I bHLH proteins were cotransfected with BHLHA9 (Figure 4). When wild-type BHLHA9 was replaced by cDNAs carrying mutations c.211A>G, c.218G>C, or c.224G>T, respectively, the potential of the three TCF proteins to activate reporter gene expression was extinguished (Figure 4). In osteosarcoma-derived U2OS cells, essentially, a comparable pattern emerged. In contrast to Cos7 cells, transfection of wild-type BHLHA9 alone resulted in a small amount of luciferase activity (Figure S5). Possibly, these cells express endogenous bHLH transcription factors able to interact with BHLHA9.

Figure 4.

Luciferase Assays Demonstrate Regulatory Activity of Coexpressed BHLHA9 and TCFs

Transient cotransfection into Cos7 cells of a construct encoding human wild-type (BH_WT) or mutant BHLHA9 (BH_N71D, BH_R73P, BH_R75L) in expression vector pCMV6-Entry/C-Myc_DDK (pCMV6), with (A) human TCF3 (TCF3), (B) human TCF4 (TCF4), or (C) human TCF12 (TCF12) in expression vectors pcDNA6.2/N-YFP-DEST (6.2YFP), and a pGL3-derived luciferase reporter gene under transcriptional control of the mouse fos-promoter with an enhancer element encompassing eight E-box sequences (8xEbox). Transient expression of BHLHA9_WT alone has no effect on luciferase activity levels. The TCFs, individually, act as strong activators. Cotransfection with BHLHA9 reduces luciferase activity levels considerably. Replacing expression of BHLHA9_WT with any of the three mutant DNAs detected in MSSD-affected individuals abolishes reporter gene activation in combination with TCF3, TCF4, and TCF12.

Transfection efficiency is normalized to cotransfected Renilla luciferase. The values obtained in transfection experiments with 8xEbox and the empty expression vectors (6.2YFP and pCMV6) are set at 0.2, and the other values are adapted accordingly. The results shown are representative of three independent experimental series, each with triplicate transfection experiments. Normalized luciferase activity (8xEbox-Luc/Ren-Luc) data are represented as mean ± SD. Repeating these experiments with a pGL4.23 derived reporter construct employing a minimal promoter did not generate significantly different results (data not shown). Repeating these experiments with osteoblast-derived cells U2OS generated results comparable to the ones obtained with Cos7 cells (Figure S5).

To test for a graded response to the level of mutants, a series of coexpression experiments with plasmids encoding human TCF3, TCF4, or TCF12 with plasmids encoding wild-type BHLHA9 alone, mutant BHLHA9 alone, or combined equal amounts of both wild-type and mutant BHLHA9 was analyzed by the luciferase assay in Cos7 cells. Compared to cotransfection of plasmids encoding wild-type BHLHA9 with plasmids encoding any of the TCFs, cotransfection of plasmids encoding wild-type and mutated BHLHA9 together with a plasmid encoding TCF decreased reporter signal levels approximately by one-third (Figure S6).

Like BHLHA9, both human HAND2 and TWIST1 expressed individually showed no impact on luciferase activity levels. Combination of HAND2 and TWIST with BHLHA9, likewise, had no activating effect (data not shown).

Discussion

The DNA-Binding Region of BHLHA9 Is Affected in MSSD-Affected Individuals

Clinical findings in affected persons from six families segregating MSSD showed a distinctive combination of developmental peculiarities in hands and feet (Figure 2, Table 1), suggesting that a gene involved in definition/separation of individual finger rays in the median segment of the limb bud is affected. We confirm the mapping of the MSSD locus to chromosome 17p13.3 and present evidence that missense mutations in BHLHA9 are associated with this phenotype. These substitutions (p.Asn71Asp, p.Arg73Pro, and p.Arg75Leu) affect neighboring amino acids in the DNA binding basic domain of the protein. This region of the transcription factor is highly conserved in evolution (Figure 3). With a sequence of 235 amino acids, BHLHA9 is small and contains in addition to the bHLH domain, a potentially functionally relevant proline-rich carboxyl terminus. Haplotype analysis of affected persons from different families carrying the same mutation suggests the presence of founder mutations (Table S2). Whereas the variant c.224G>T (p.Arg75Leu), so far, was observed in only one family of European ancestry, the presence of identical haplotypes each associated with a different BHLHA9 mutation in two reportedly unrelated families from Pakistan and two families from Turkey, respectively, hints at no fewer than three founder mutations in the Middle East.

Missense Mutations Exchanging Homologous Amino Acids in Potential Dimerization Partners for BHLHA9 Elucidate Functional Defects Underlying MSSD

The amino acids Asn71, Arg73, and Arg75, affected in MSSD, are identical in the BHLHA9 orthologs in vertebrates as well as in many other bHLH proteins, such as TCF3 (E12/E47), TCF4, TCF12, TWIST1, HAND2, and NEUROD1 (Figure 3). Y2H analysis indicates that BHLHA9 is able to interact (dimerize) with itself, the bHLH E-box proteins TCF3, TCF4, and TCF12, as well as with TWIST1 and HAND2 (Figure S4). Like these proteins,17 YFP-tagged wild-type or mutant BHLHA9 proteins localize in the nucleus of transfected cells in addition to the cytoplasm (Figure S3). No nuclear localization signal is predicted for BHLHA9; however, with a mass of 24,132 Da, the protein might enter the nucleus by passive transport.

The TCFs encode widely expressed bHLH E-box proteins that heterodimerize with cell-specific bHLH proteins such as BHLHA9, TWIST1, HAND2, or NEUROD1. E-box proteins are potent regulators of gene expression that bind on E-box-containing promoters. The heterogeneity in the E-box sequence that is recognized and the dimers formed by different bHLH proteins determines how they control diverse developmental functions through activating or repressing transcriptional regulation.18

By using a transactivation assay, we found that expression of BHLHA9 alone did not significantly enhance expression of a fos- or minimal promoter-driven reporter gene containing eight E-boxes.16 Combination of native BHLHA9 with each of the three E-box proteins strongly reduced reporter gene expression relative to homodimers of each. The activation by the E-box proteins was completely blocked in the presence of the BHLHA9 missense mutations encoding the p.Asn71Asp, p.Arg73Pro, and p.Arg75Leu substitutions (Figures 4 and S5).

Our observations are congruent with the functional consequences of substitutions of these invariant orthologous amino acids reported for other bHLH proteins (Figure 3).

Mutations affecting in the E-box protein TCF4 amino acids orthologous to the ones described here for BHLHA9 cause Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (PTHS [MIM 610954]).19–22 Their substitution in TWIST1 and NEUROD1 causes Saethre-Chotzen syndrome (SCS [MIM 101400])23,24 and type II diabetes mellitus (NIDDM [MIM 125853]), respectively. In addition, the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC)25 lists missense mutations in tumor cells affecting these sites (Figure 3).

It should be noted that the mutations affecting the orthologous amino acids in the DNA-binding regions of TCF4, TWIST1, and NEUROD1 cause dominant phenotypes whereas MSSD is recessive.

Individuals heterozygous for one of the described BHLHA9 mutations do not have MSSD. Accordingly, luciferase assays employing coexpression of human TCF3, TCF4, or TCF12 with equal amounts of wild-type and mutant BHLHA9 demonstrated a decrease in reporter gene expression, compared to BHLHA9wt/TCF alone, but not complete loss of activation (Figure S6).

By analogy to functional consequences reported for missense mutations altering conserved amino acids in identical positions of the basic DNA-binding domains of bHLH proteins,26 we assume that BHLHA9 might likewise act in limb development as a dimerization partner of the TCFs or other E-box-binding proteins and that the detrimental effect of the BHLHA9 missense mutations on limb development might be caused by the complete loss of the regulatory potential of the dimers.

Syndactyly phenotypes associated with mutations affecting other bHLH proteins, such as MYCN (MIM 164840), suggest further candidates that might be fine tuned by dimerizing with BHLHA9.27

Similar Hand Phenotypes in Individuals Mildly Affected by CLS and MSSD

Cenani-Lenz syndactyly, the second autosomal-recessive syndactyly, is associated with mutations in low-density lipoprotein-related protein 4 receptor (LRP4 [MIM 604270]) on chromosome 11p11.2-q13.1, resulting in deregulated canonical WNT signaling.28

Affected persons from six families that demonstrated MSSD associated with BHLHA9 mutation showed a distinctive combination of developmental peculiarities in hands and feet (Figure 2), but no features such as prominent forehead, hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures, micrognathia, and kidney anomalies, which have been reported in Cenani-Lenz syndrome.28–30 The MSSD limb phenotype is more uniform in contrast to the malformations in CLS, which range from partial to total syndactyly and bone malformations of both hands and feet. Notably, in some CLS individuals, a mild hand phenotype reminiscent of MSSD appears.30,31 This partial phenotypic overlap suggests involvement of a regulatory pathway involved in limb development that is influenced by both LRP4 and BHLHA9. LRP4 mutations interfere with the WNT1/β-Catenin-TWIST1 signaling chain, particularly in cells prone to apoptosis in the median segment of the limb bud.28,31 This signaling plays a key role in the mouse limb bud, establishing a pattern of graded strength of SHH signaling across the anterior-posterior dimension.32,33 Under the influence of SHH from the ZPA, separate digits are produced by regression of interdigital tissue via apoptosis, dependent on BMP signaling within the interdigital tissue. Disruption of this process can result in syndactyly.32 Altered BHLHA9 might interfere with this function, perhaps by the similarity with the bHLH proteins TWIST1 and its antagonist HAND2. Both are able to bind BHLHA9, as demonstrated in Y2H analysis (Figure S4), and one or both might compete with BHLHA9 for the same partners for dimerization. However, direct functional interaction is unlikely because in the experimental system employed here, dimers of these proteins with wild-type or mutant BHLHA9 did not influence reporter gene expression in transfected cells (data not shown). Experimental evidence for a mechanistic link between LRP4 and BHLHA9 has to be awaited.

Which one of the potential bHLH dimerization partners for BHLHA9 is chosen during limb development, and whether any of the postulated mechanisms are responsible for the loss of function causing the specific malformations of MSSD await future experimental clarification.

Different Clinical Phenotypes Associated with BHLHA9 Malfunction

In addition to MSSD associated with BHLHA9 missense mutations in the DNA-binding domain, involvement of this protein in the regulation of osteoblast differentiation in the median segment of the distal limb bud mesenchyme is suggested by the phenotypes observed with copy-number variants (CNVs) of chromosome 17p13.3 in humans or studies in model organisms.

In humans, hemizygous duplications of 17p13.3 segments are associated in non-Mendelian fashion with split-hand/foot malformation with long-bone deficiency (SHFLD3), and the smallest region of overlap, encasing only BHLHA9, defines this gene as a strong candidate for the bone phenotypes.6,8–11,34

The high degree of nonpenetrance and a sex bias are attributed to modifiers not identified yet.11,34 The notion that functional deficiency of BHLHA9 might be responsible for SHFLD3 is also compatible with the limb expression pattern of this gene restricted to the mesenchyme underlying the apical ectodermal ridge in mouse and zebrafish embryos11,14 and with the expression of a LacZ reporter gene replacing the coding region of Bhlha9 in Bhlha9 (Fingerin)/lacZ knockout/knockin mice.13 Bhlha9 knockdown in zebrafish results in shortening of pectoral fins.11 Most of homozygous Bhlha9 (Fingerin)Null mice displayed various degrees of simple incomplete webbing of forelimb digits 2–3 involving soft tissue. Incomplete finger separation was detectable already during embryogenesis and correlated with reduced interdigital apoptosis.13

Both missense mutations in humans and knockout of the coding exon in mice, expected to result in complete absence of BHLHA9, generate limb malformations only in homozygotes. However, the molecular consequences for function of a dimerizing partner bHLH protein are different (Figures 4 and S5), as are the phenotypes in mice or humans. Whereas MSSD associated with exclusive presence of BHLHA9 with deficient DNA-binding capacity demonstrates a distinctive combination of clinical features which include mesoaxial osseous synostosis at metacarpal level, reduction of one or more phalanges, hypoplasia of distal phalanges of preaxial and postaxial digits, clinodactyly of fifth fingers, and preaxial fusion of toes, complete absence of the Bhlha9 coding sequence in knockout mice results in a less severe and different type of syndactyly, i.e., webbing of forelimb digits 2–3 without bone fusion.

In contrast, SHFLD3 is dominant. Part of the spectrum of phenotypic entities resulting from duplications of 17p13.3 are associated with the different length of the microduplications, encasing flanking genes in addition to BHLHA9, and will not be discussed here. The wide range of SHFLD3 limb phenotypes is considered to be specifically associated with a detrimental effect of the gene duplication on BHLHA9 function. In rare cases, the syndactyly in individuals heterozygous for BHLHA9 duplications is reminiscent of the MSSD phenotype, but these CNV carriers, in addition, exhibit a split hand.6,10 These phenotypically similar cases suggest that the functional outcome of the malfunctioning BHLHA9 should be similar to the consequences of a third gene copy.

In the cotransfection experiments, wild-type BHLHA9 diminished the transcription-activating potential of type I E-box-binding proteins considerably, leaving only a small amount of residual activity (Figures 4 and S5). BHLHA9 proteins with dysfunctional DNA-binding sequences did not retain this fine-tuning regulatory potential but rather extinguished gene activation. Likewise, increasing the amount of available inhibitory wild-type BHLHA9 by usage of a third gene copy might further reduce transcription of sensitive target genes. The high degree of nonpenetrance in SHFLD3 might be associated with allelic heterogeneity in the dimerizing bHLH partners, in the target gene regulatory domains, or with stochastic differences in the transcription and translation of overdosed BHLHA9 copies.

This model is open to analysis of the physiological role of BHLHA9 in the limb bud and to quantification of this function in models of SHFLD3 and MSSD. It should be noted that the presence of only one single exon of BHLHA9 is speculative and that the start and end of transcription as well as the regulatory environment of this gene are undetermined. Genetic studies with models featuring missense mutations identical to the ones found in MSSD are needed to shed light on the consequences of deficient BHLHA9 DNA binding domains on the well-established transcription factor network governing limb patterning.

Acknowledgments

The participation of the individuals and their families in this study is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Howard Cann (CEPH, Paris, France) for a control DNA sample, M. Sigvardsson (Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden) for reporter vectors, Manfred Koegl, Frank Schwarz, and Sara Burmester (DKFZ Heidelberg, Germany) for plasmid production and advice on interpretation of Y2H data, Michael Pütz (Marburg) for helpful discussions and advice on graphical presentations, and Ulrike Neidel (Marburg) for competent technical assistance. This research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (Gr373-21; GRK 767), Stiftungen P.E. Kempkes and Emil von Behring, Marburg, Germany, Cumhuriyet University Research Committee, Turkey (CUBAP) (grant number T-180), and Higher Education Commission, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

1000 Genomes, http://browser.1000genomes.org

COSMIC, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/

International HapMap Project, http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

MutationTaster, http://www.mutationtaster.org/

MutPred, http://mutpred.mutdb.org/

NCBI Nucleotide, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/

NCBI Protein, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org/

PolyPhen-2, http://www.genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu

Accession Numbers

Data on the BHLHA9 variants associated with MSSD are deposited in ClinVar with the accession numbers SCV000189863, SCV000189864, and SCV000189865.

References

- 1.Malik S., Arshad M., Amin-Ud-Din M., Oeffner F., Dempfle A., Haque S., Koch M.C., Ahmad W., Grzeschik K.H. A novel type of autosomal recessive syndactyly: clinical and molecular studies in a family of Pakistani origin. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;126A:61–67. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik S., Percin F.E., Ahmad W., Percin S., Akarsu N.A., Koch M.C., Grzeschik K.H. Autosomal recessive mesoaxial synostotic syndactyly with phalangeal reduction maps to chromosome 17p13.3. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;134:404–408. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Percin E.F., Percin S., Egilmez H., Sezgin I., Ozbas F., Akarsu A.N. Mesoaxial complete syndactyly and synostosis with hypoplastic thumbs: an unusual combination or homozygous expression of syndactyly type I? J. Med. Genet. 1998;35:868–874. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.10.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik S. Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;20:817–824. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik S., Ahmad W., Grzeschik K.-H., Koch M.C. A simple method for characterising syndactyly in clinical practice. Genet. Couns. 2005;16:229–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lezirovitz K., Maestrelli S.R., Cotrim N.H., Otto P.A., Pearson P.L., Mingroni-Netto R.C. A novel locus for split-hand/foot malformation associated with tibial hemimelia (SHFLD syndrome) maps to chromosome region 17p13.1-17p13.3. Hum. Genet. 2008;123:625–631. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richieri-Costa A., Brunoni D., Laredo Filho J., Kasinski S. Tibial aplasia-ectrodactyly as variant expression of the Gollop-Wolfgang complex: report of a Brazilian family. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1987;28:971–980. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320280424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petit F., Andrieux J., Demeer B., Collet L.M., Copin H., Boudry-Labis E., Escande F., Manouvrier-Hanu S., Mathieu-Dramard M. Split-hand/foot malformation with long-bone deficiency and BHLHA9 duplication: two cases and expansion of the phenotype to radial agenesis. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2013;56:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petit F., Jourdain A.S., Andrieux J., Baujat G., Baumann C., Beneteau C., David A., Faivre L., Gaillard D., Gilbert-Dussardier B. Split hand/foot malformation with long-bone deficiency and BHLHA9 duplication: report of 13 new families. Clin. Genet. 2014;85:464–469. doi: 10.1111/cge.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armour C.M., Bulman D.E., Jarinova O., Rogers R.C., Clarkson K.B., DuPont B.R., Dwivedi A., Bartel F.O., McDonell L., Schwartz C.E. 17p13.3 microduplications are associated with split-hand/foot malformation and long-bone deficiency (SHFLD) Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;19:1144–1151. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klopocki E., Lohan S., Doelken S.C., Stricker S., Ockeloen C.W., Soares Thiele de Aguiar R., Lezirovitz K., Mingroni Netto R.C., Jamsheer A., Shah H. Duplications of BHLHA9 are associated with ectrodactyly and tibia hemimelia inherited in non-Mendelian fashion. J. Med. Genet. 2012;49:119–125. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLellan A.S., Langlands K., Kealey T. Exhaustive identification of human class II basic helix-loop-helix proteins by virtual library screening. Mech. Dev. 2002;119(1):S285–S291. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schatz O., Langer E., Ben-Arie N. Gene dosage of the transcription factor Fingerin (bHLHA9) affects digit development and links syndactyly to ectrodactyly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:5394–5401. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray P.A., Fu H., Luo P., Zhao Q., Yu J., Ferrari A., Tenzen T., Yuk D.I., Tsung E.F., Cai Z. Mouse brain organization revealed through direct genome-scale TF expression analysis. Science. 2004;306:2255–2257. doi: 10.1126/science.1104935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murre C., Bain G., van Dijk M.A., Engel I., Furnari B.A., Massari M.E., Matthews J.R., Quong M.W., Rivera R.R., Stuiver M.H. Structure and function of helix-loop-helix proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1218:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigvardsson M. Overlapping expression of early B-cell factor and basic helix-loop-helix proteins as a mechanism to dictate B-lineage-specific activity of the lambda5 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:3640–3654. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3640-3654.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C., Bian W., Xia C., Zhang T., Guillemot F., Jing N. Visualization of bHLH transcription factor interactions in living mammalian cell nuclei and developing chicken neural tube by FRET. Cell Res. 2006;16:585–598. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones S. An overview of the basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Genome Biol. 2004;5:226. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-6-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amiel J., Rio M., de Pontual L., Redon R., Malan V., Boddaert N., Plouin P., Carter N.P., Lyonnet S., Munnich A., Colleaux L. Mutations in TCF4, encoding a class I basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, are responsible for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a severe epileptic encephalopathy associated with autonomic dysfunction. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:988–993. doi: 10.1086/515582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Pontual L., Mathieu Y., Golzio C., Rio M., Malan V., Boddaert N., Soufflet C., Picard C., Durandy A., Dobbie A. Mutational, functional, and expression studies of the TCF4 gene in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:669–676. doi: 10.1002/humu.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zweier C., Peippo M.M., Hoyer J., Sousa S., Bottani A., Clayton-Smith J., Reardon W., Saraiva J., Cabral A., Gohring I. Haploinsufficiency of TCF4 causes syndromal mental retardation with intermittent hyperventilation (Pitt-Hopkins syndrome) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:994–1001. doi: 10.1086/515583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zweier C., Sticht H., Bijlsma E.K., Clayton-Smith J., Boonen S.E., Fryer A., Greally M.T., Hoffmann L., den Hollander N.S., Jongmans M. Further delineation of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: phenotypic and genotypic description of 16 novel patients. J. Med. Genet. 2008;45:738–744. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.060129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Ghouzzi V., Legeai-Mallet L., Benoist-Lasselin C., Lajeunie E., Renier D., Munnich A., Bonaventure J. Mutations in the basic domain and the loop-helix II junction of TWIST abolish DNA binding in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. FEBS Lett. 2001;492:112–118. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard T.D., Paznekas W.A., Green E.D., Chiang L.C., Ma N., Ortiz de Luna R.I., Garcia Delgado C., Gonzalez-Ramos M., Kline A.D., Jabs E.W. Mutations in TWIST, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, in Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:36–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bamford S., Dawson E., Forbes S., Clements J., Pettett R., Dogan A., Flanagan A., Teague J., Futreal P.A., Stratton M.R., Wooster R. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;91:355–358. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maia A.M., da Silva J.H., Mencalha A.L., Caffarena E.R., Abdelhay E. Computational modeling of the bHLH domain of the transcription factor TWIST1 and R118C, S144R and K145E mutants. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:184. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ota S., Zhou Z.Q., Keene D.R., Knoepfler P., Hurlin P.J. Activities of N-Myc in the developing limb link control of skeletal size with digit separation. Development. 2007;134:1583–1592. doi: 10.1242/dev.000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y., Pawlik B., Elcioglu N., Aglan M., Kayserili H., Yigit G., Percin F., Goodman F., Nürnberg G., Cenani A. LRP4 mutations alter Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and cause limb and kidney malformations in Cenani-Lenz syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:696–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cenani A., Lenz W. Totale Syndaktylie und totale radioulnare Synostose bei zwei Brüdern. Z. Kinderheilkd. 1967;101:181–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan T.N., Klar J., Ali Z., Khan F., Baig S.M., Dahl N. Cenani-Lenz syndrome restricted to limb and kidney anomalies associated with a novel LRP4 missense mutation. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2013;56:371–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leupin O., Piters E., Halleux C., Hu S., Kramer I., Morvan F., Bouwmeester T., Schirle M., Bueno-Lozano M., Fuentes F.J. Bone overgrowth-associated mutations in the LRP4 gene impair sclerostin facilitator function. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:19489–19500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krawchuk D., Weiner S.J., Chen Y.T., Lu B.C., Costantini F., Behringer R.R., Laufer E. Twist1 activity thresholds define multiple functions in limb development. Dev. Biol. 2010;347:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Rourke M.P., Tam P.P. Twist functions in mouse development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2002;46:401–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capra V., Mirabelli-Badenier M., Stagnaro M., Rossi A., Tassano E., Gimelli S., Gimelli G. Identification of a rare 17p13.3 duplication including the BHLHA9 and YWHAE genes in a family with developmental delay and behavioural problems. BMC Med. Genet. 2012;13:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchler-Bauer A., Lu S., Anderson J.B., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M.K., DeWeese-Scott C., Fong J.H., Geer L.Y., Geer R.C., Gonzales N.R. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sepp M., Pruunsild P., Timmusk T. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome-associated mutations in TCF4 lead to variable impairment of the transcription factor function ranging from hypomorphic to dominant-negative effects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2873–2888. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.