Abstract

Background:

Chromium supplementations (Cr) have been shown to exert beneficial effects in the management of type-2 diabetes. Prevalence of Cr deficiency in pre-diabetic patients is not well-understood, therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the extent of this prevalence.

Materials and Methods:

In this cross-sectional descriptive study, 132 pre-diabetic patients were recruited. The participants were randomly selected from those who referred to the Shariati Hospital in Isfahan, Iran. Blood samples are collected for measurement of Cr, insulin, fasting blood sugar (FBS), and two-hour post-load plasma glucose. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Determination of Cr was carried out by atomic absorption spectrometry.

Results:

Thirty-four (31.5%) patients had Cr deficiency and 74 (68.5%) patients had normal Cr. There was no significant difference between sex, age groups (<50 years and ≥50 years) and between patients with and without a family history of diabetes in both the groups. No significant differences in age, BMI, FBS or insulin were observed between two groups. In the group with a normal level of Cr, there was a significant reversed correlation between the Cr level and age, but no significant correlation existed between the Cr level and other factors in both groups.

Conclusion:

The levels of Cr deficiency are relatively common in patients with pre-diabetes, and it is necessary to screen patients with diabetes and pre-diabetes according to the American Diabetes Association guidelines, with regard to the Cr level and action should be taken to eliminate the Cr deficiency in these patients.

Keywords: Chromium, insulin, pre-diabetic

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus, a well-known endocrine metabolic disorder, is a disease characterized by high levels of blood glucose and multiple tissue complications, resulting in nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.[1] Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), impaired fasting glucose (IFG), and metabolic syndrome are considered precursors to type 2 diabetes mellitus.[2] The presence of IGT and IFG is called pre-diabetes.[3] A significant increase in the costs of long-term treatment of diabetes and its complications is felt.[4] Although pharmacotherapy can reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes,[5] their cost and potential adverse effects can be objectionable to patients who do not yet have the actual disease.[6] Intensive diet and lifestyle changes can have an important role in diabetes prevention.[7] Chromium (Cr) may help people with type 2 diabetes by improving insulin resistance and increasing the body's sensitivity to insulin.[3] Cr is considered an essential element for humans.[8] A diet lacking in this element may result in the development of diabetes mellitus.[8]

Cr is required for normal carbohydrate, protein, and lipid metabolism and its deficiency has been implicated as one of the causes of diabetes mellitus.[9,10] Most of the current knowledge on the effects of Cr on glucose homeostasis comes from clinical studies examining the effect of Cr supplementation on glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. Results from these studies have been inconclusive.[11,12]

In the present research, with regard to diabetes prevalence and a need to give special attention to its prevention and the effect of Cr on diabetes, we investigate the effect of the Cr level in the prediction of diabetes in pre-diabetic patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional descriptive study was designed to evaluate the effect of the Cr level on the prediction of diabetes in pre-diabetic patients. The study was conducted in 2012, and 132 pre-diabetic patients, with the mean age of 52.8 ± 13.3 years, were recruited.

The participants were randomly selected from those who referred to the Shariati Hospital (Isfahan, Iran). The allocation was conducted using random numbers generated by the computer, using the participants’ record numbers in the clinic. The blood tests used to measure plasma glucose and diagnose pre-diabetes included a fasting plasma glucose (FBS) test and a glucose tolerance test. Individuals with a fasting plasma glucose level between 100 and 125 mg/dl were referred to as having impaired fasting glucose. Individuals with plasma glucose levels of 140-199 mg/dl after a two-hour oral glucose tolerance test were referred to as having impaired glucose tolerance.[13] Patients were excluded if they were taking antidiabetic drugs or Cr supplementation. The demographic details were taken from the participants and their parents. This study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University.

All measurements were made by a trained team of general physicians and nurses under the supervision of the same pediatrician. Anthropometric and biochemical measurements were conducted using calibrated instruments and standard protocols after participant selection. Fasting venous blood samples were collected from participants to measure the biochemical factors. Blood glucose was determined using the glucose oxidase assay and insulin levels were determined using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A two-hour post-load plasma glucose test (2 hpp) was performed twice by venous blood sampling (in a fasting state and two hours after drinking a glucose solution) in all participants. Determination of Cr was carried out by atomic absorption spectrometry (Agilent, USA).[14] Calculation of body mass index (BMI) was done by dividing weight (in kilograms) by height (in meters squared).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS program (Version 15, Chicago, IL, USA). The data were presented as means with standard deviation (SD). The chi-square and Fisher tests were used for all comparisons between the qualitative data and the T test was applied to compare the quantitative data. The Pearson's correlation was used for investigation of the studied factors and Cr levels. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

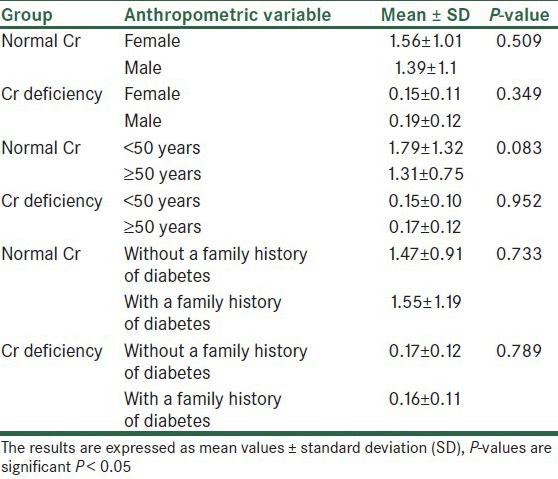

In this study, 132 patients were investigated but 24 patients didn’t complete their laboratory studies and were not included in the final statistical analyses. The mean and standard deviation of serum Cr was 1.08 ± 1.06 μg/L. Thirty-four (31.5%) patients had Cr deficiency and 74 (68.5%) patients had normal Cr. Table 1 illustrates that there is no significant difference between men and women, between the investigated age groups (<50 years and ≥50 years), and between patients with and without a family history of diabetes, in both the groups.

Table 1.

The Cr levels (μg/L) based on sex, age, and family history of diabetes in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

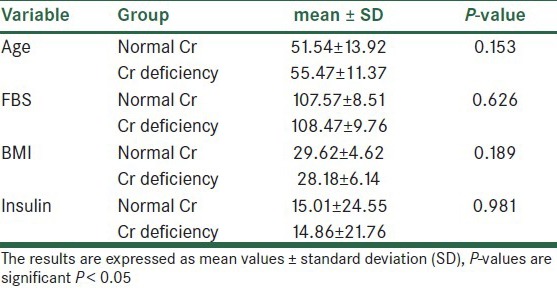

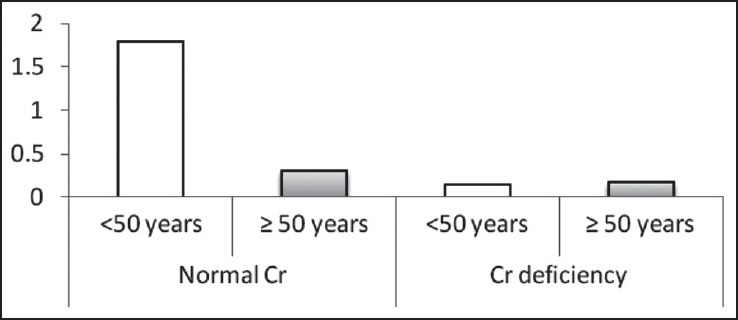

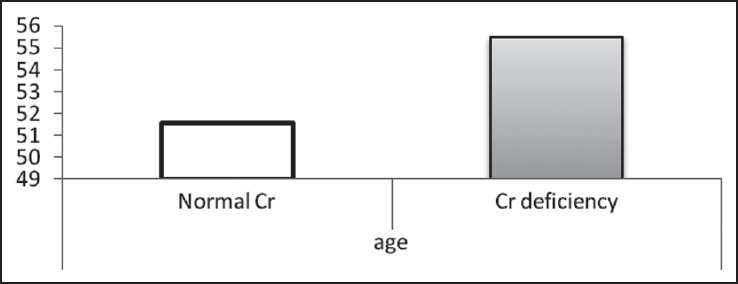

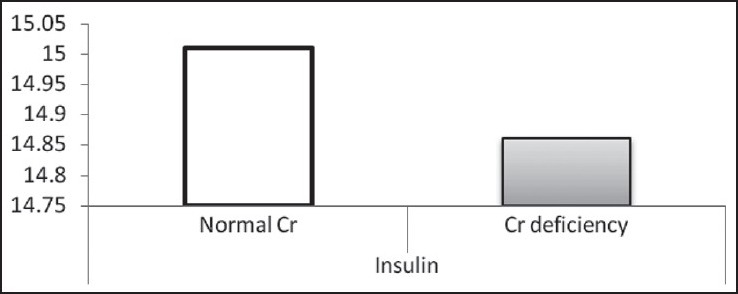

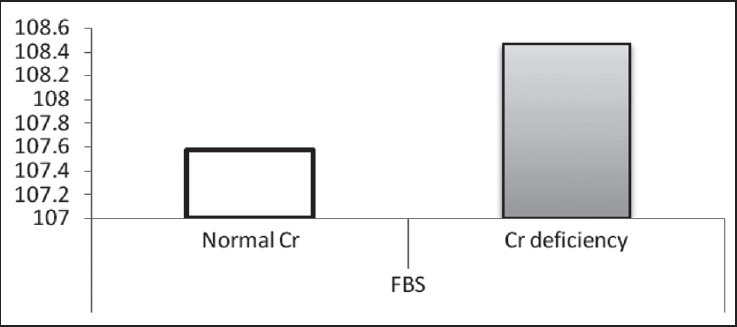

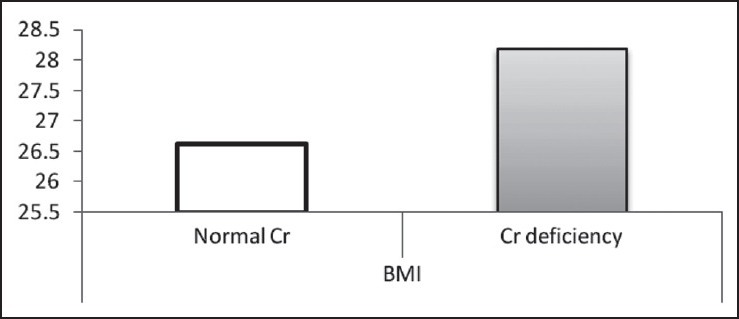

According to the findings, as shown in Table 2 and Figures 1–3, no significant difference was observed in age and BMI, as well as FBS and insulin, between the two groups. Cr deficiency occured at higher levels of FBS and BMI, but at older ages they were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Biochemical and anthropometric variables in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

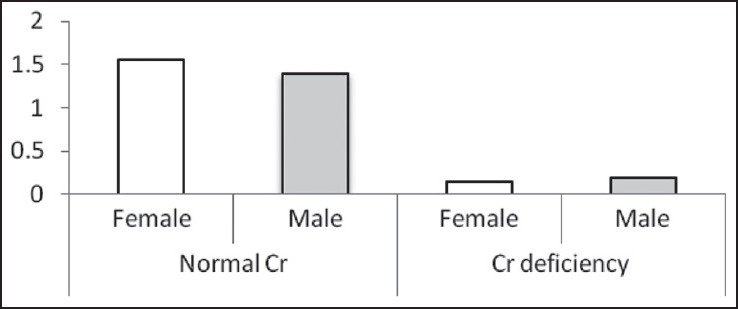

Figure 1.

The Cr levels (μg/L) based on sex in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

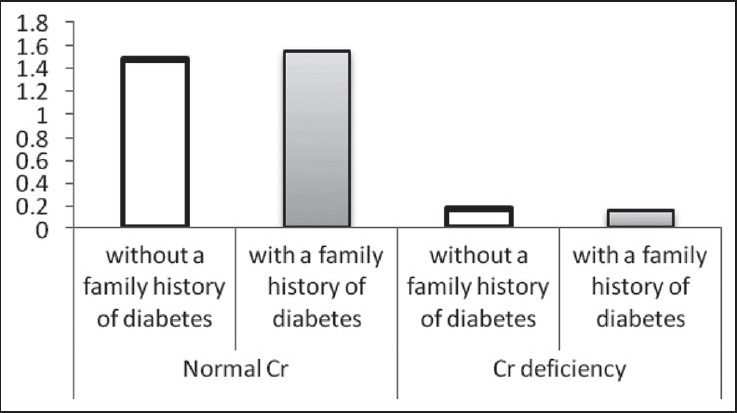

Figure 3.

The Cr levels (μg/L) based on family history of diabetes in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

Figure 2.

The Cr levels (μg/L) based on age in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

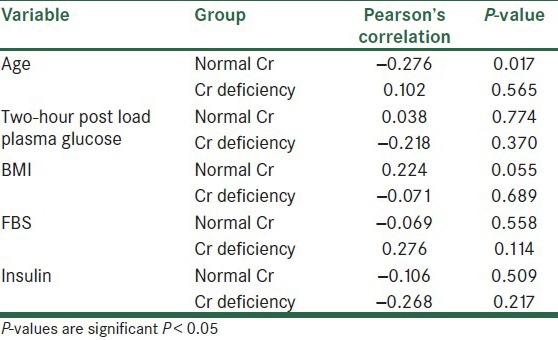

Findings on the correlation between Cr and the biochemical factors of blood in the normal Cr and the Cr-deficiency groups are summarized in Table 3 and Figures 4–7. In the group with a normal level of Cr, there was a significant reversed correlation between the Cr level and age, but no significant correlation existed between the Cr level and other factors in both groups.

Table 3.

Correlation between Cr level and biochemical and anthropometric variables in two normal Cr and CrMean of age in two-deficiency groups

Figure 4.

Mean of age in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

Figure 7.

Mean of insulin in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

Figure 5.

Mean of FBS in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

Figure 6.

Mean of BMI in two normal Cr and Cr-deficiency groups

DISCUSSION

Chromium is believed to be an insulin-sensitizing agent and may facilitate insulin attachment to the insulin receptor.[15] Cr may improve insulin sensitivity by activating the insulin receptor tyrosine kinase, an effect that has been shown in rats,[16] and also by inhibiting phosphotyrosine phosphatase, which is a rat homolog of human tyrosine phosphatase, which inactivates the activated (phosphorylated) insulin receptor. Thus, Cr may promote phosphorylation, and hence, the activation of the insulin receptor, leading to an improvement in insulin sensitivity.[16]

One of the reviews has identified 16 studies on Cr supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Of these studies, 13 show a significant improvement in glucose, insulin, and lipid concentrations. These studies include a total of 502 patients. There are three studies, with a total of 55 subjects, in which no effect has been found.[17] Cr has a positive effect on glucose tolerance and diabetes, but all the studies do not involve these effects for a number of reasons. First of all, human studies include subjects of diverse genetic and nutritional backgrounds, living in environments of varying degrees of stress, all of which may affect Cr metabolism.[18] Varying results of supplemental Cr may also be due to the diet, selection of subjects, the duration of the study, as also the amount and type of supplemental Cr. In addition, response to Cr is related to the degree of glucose intolerance. Subjects with better glucose tolerance, who do not need additional Cr, do not respond to supplemental Cr.[19]

The study by Tripathy et al.[20] was conducted on 30 type-2 diabetic subjects and 30 age-matched control subjects within the age range of 40-55 years. Glucose and Cr were analyzed in the fasting serum of all the subjects. Diabetic subjects had significantly lower serum concentrations of Cr as compared to the controls and exhibited a significant increase in serum glucose levels. The serum levels of glucose were found to be negatively correlated to the serum levels of Cr of diabetic patients. The lower serum levels of Cr in diabetics compared to control patients could due to the poor glycemic control.[20] Cr supplementation had variable effects on the body weight of patients with diabetes.[21,22] One study of patients with diabetes using Cr indicated no significant effects on either body weight or BMI,[21] while of the eight double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in individuals without diabetes, Cr supplementation showed a decrease in weight and fat in three larger studies.[22] Ding et al.[23] revealed that serum Cr was similar in women and men, while in the results of the Ravina et al.[24] study, the blood Cr level was lower in women than in men. In the present study, the number of women with Cr deficiency was more than men, which was consistent with the Ding et al.[23] study. The difference in the results could be due to differences in nutrition and geographic area. Duncan et al.[25] concluded that increasing age and family history of diabetes led to insulin resistance in diabetic patients, due to reduction in blood levels of Cr. In our study, in patients with a deficiency of Cr, the number of patients ≥50 years old and with a family history of diabetes was more than the others, however, it was not significant. Based on the results achieved from this study, the number of pre-diabetic patients with deficiency of Cr than patients with normal level of Cr was not negligible, and it could be seen as a warning for the onset of diabetes.

According to the effect of varying factors, including nutrition, race and environment played a role in diabetes. This was suggested, and further studies should be conducted, with larger sample sizes. Risk factors for diabetes investigate in the future also.

CONCLUSION

With regard to the Cr deficiency in pre-diabetes patients and the effect of this element on blood glucose and insulin sensitivity, screening for pre-diabetic should be done (according to the American Diabetes Association) and the levels of Cr be investigated in these patients in order to perform the appropriate action for the removal of Cr deficiency and prediction of diabetes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the authorities at the Islamic Azad University, Najafabad branch, for their financial support for this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sicree R, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ. The global burden of diabetes. In: Gan D, editor. Diabetes Atlas. 2nd ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2003. pp. 15–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 1):S62–7. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali A, Ma Y, Reynolds J, Wise JP Sr, Inzucchi SE, Katz DL. Chromium effects on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in persons at risk for diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:16–25. doi: 10.4158/EP10131.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin CG, Davidson JA. Value of self-monitoring blood glucose pattern analysis in improving diabetes outcomes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:500–8. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padwal R, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Varney J, McAlister FA. A systematic review of drug therapy to delay or prevent type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:736–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker EA, Molitch M, Kramer MK, Kahn S, Ma Y, Edelstein S, et al. Adherence to preventive medications: Predictors and outcomes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1997–2002. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afridi HI, Kazi TG, Brabazon D, Naher S, Talpur FN. Comparative metal distribution in scalp hair of Pakistani and Irish referents and diabetes mellitus patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;415:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YQ, Yao MH. Effects of chromium picolinate on glucose uptake in insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 adipocytes involve activation of p38 MAPK. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20:982–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon MJ, Chung HS, Yoon CS, Ko JH, Jun HJ, Kim TK, et al. The effect of chromium on rat insulinoma cells in high glucose conditions. Life Sci. 2010;87:401–4. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balk EM, Tatsioni A, Lichtenstein AH, Lau J, Pittas AG. Effect of chromium supplementation on glucose metabolism and lipids: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2154–63. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vincent JB. Amsterdam, Boston: Elsevier; 2007. The Nutritional Biochemistry of Chromium (III) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips LS, Weintraub WS, Ziemer DC, Kolm P, Foster JK, Vaccarino V, et al. All pre-diabetes is not the same: Metabolic and vascular risks of impaired fasting glucose at 100 versus 110 mg/dl: The screening for impaired glucose tolerance study 1 (SIGT 1) Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1405–7. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nawrocka A, Szkoda J. Determination of chromium in biological material by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry method. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2012;56:585–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mertz W, Toepfer EW, Roginski EE, Polansky MM. Present knowledge of the role of chromium. Fed Proc. 1974;33:2275–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis CM, Vincent JB. Chromium oligopeptide activates insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4382–5. doi: 10.1021/bi963154t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunton JE, Hams G, Hitchman R, McElduff A. Serum chromium does not predict glucose tolerance in late pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:99–104. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson RA. Stress effects on chromium nutrition of humans and farm animals. In: Anonymous, editor. Proceedings of Alltech's Tenth Symposium on Biotechnology in the Feed Industry. Nottingham, England: University Press; 1994. pp. 267–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson RA. Recent advances in the clinical and biochemical effects of chromium deficiency. In: Prasad AS, editor. Essential and Toxic Trace Elements in Human Health and Disease. New York: Wiley Liss; 1993. pp. 221–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tripathy S, Sumathi S, Raj GB. Minerals nutritional status of type 2 diabetic subjects. Int J Diab Dev Countries. 2004;24:27–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cefalu WT, Rood J, Pinsonat P, Qin J, Sereda O, Levitan L, et al. Characterization of the metabolic and physiologic response to chromium supplementation in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2010;59:755–62. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell WW, Joseph LJ, Anderson RA, Davey SL, Hinton J, Evans WJ. Effects of resistive training and chromium picolinate on body composition and skeletal muscle size in older women. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12:125–35. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.12.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding W, Chai Z, Duan P, Feng W, Qian Q. Serum and urine chromium concentrations in elderly diabetics. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1998;63:231–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02778941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravina A, Slezack L. Chromium in the treatment of clinical diabetes mellitus. IMAJ. 1993;125:142–5. 191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan MG. The effects of nutritional supplements on the treatment of depression, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia in the renal patient. J Ren Nutr. 1999;9:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(99)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]