Abstract

Blood transfusion is an essential component of emergency obstetric care and appropriate blood transfusion significantly reduces maternal mortality. Obstetric haemorrhage, especially postpartum haemorrhage, remains one of the major causes of massive haemorrhage and a prime cause of maternal mortality. Blood loss and assessment of its correct requirement are difficult in pregnancy due to physiological changes and comorbid conditions. Many guidelines have been used to assess the requirement and transfusion of blood and its components. Infrastructural, economic, social and religious constraints in blood banking and donation are key issues to formulate practice guidelines. Available current guidelines for transfusion are mostly from the developed world; however, they can be used by developing countries keeping available resources in perspective.

Keywords: Obstetric anaesthesia, obstetric haemorrhage, postpartum haemorrhage, transfusion practices, transfusion protocol

INTRODUCTION

Blood transfusion is recognised as one of the eight essential components of the Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care module, which has been designed to reduce maternal mortality rates. Postpartum haemorrhage is a major contributor which accounts for 25% of all pregnancy-related deaths.[1] Availability of blood transfusion in developing countries depends on infrastructure, economics and social and religious taboos and practices, and this could cause transfusion practices to vary from those in the developed countries.[2]

CHALLENGES OF BLOOD TRANSFUSIONS IN OBSTETRIC PATIENT

Transfusion in obstetric patients poses challenges due to changes in maternal physiology, risk of alloimmunisation and infections in the foetus. While indications for transfusion in obstetrics may be emergent as well as nonemergent, the keystone of transfusion practice is that it should be appropriate that is, not given when not required and not missed when required. Transfusion guidelines have been designed by various organisations in various countries. While the basic tenets remain the same, availability of resources decide the practice.

PROBLEMS SPECIFIC TO THE PREGNANT PATIENT

Physiological changes in pregnancy

Increase in red cell mass (20-30%) and disproportionately greater increase in plasma volume (50%) help the patient stay haemodynamically stable with the normal blood loss during delivery. A hypercoagulable state prevails in pregnancy, with increased fibrinogen and factors VII, VIII, and IX supervening over the rise in the natural anticoagulants, Protein A, Protein C, and Antithrombin III. The fibrinolytic system decreases in activity. Plasminogen is increased, but its activity is dampened by a corresponding increase in plasminogen inhibitor type II. An exception to the general increase in coagulation factors is the fall in platelet levels, the so-called gestational thrombocytopenia.

Difficulty in assessment of blood loss

Assessment of blood loss by vital signs monitoring is unreliable in pregnancy, due to the increased maternal plasma volume. The relative haemodilution and high cardiac output allows the large amount of blood loss in a pregnant female before the hypotension and fall in haemoglobin/haematocrit (Hct) ensues. The assessment may also be farce because large amounts of blood lost may be concealed in the uterine cavity.

Associated comorbid conditions like preeclampsia, thrombocytopenia and the HELLP syndrome can bring about catastrophic haemorrhage. While the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy helps limit blood loss, it can tip the mother into disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) and pulmonary embolism.

Risk to foetus

While managing acute haemorrhagic emergencies, the foetus has to be kept in mind, to prevent infections and avoid Haemolytic Disease of the Foetus and Newborn (HDFN) in the current and future pregnancies.

INDICATIONS OF BLOOD TRANSFUSION IN OBSTETRICS

Anaemia of pregnancy and Haemoglobinopathies

Obstetric haemorrhage

Surgeries where significant blood loss is expected.

BLOOD TRANSFUSION FOR ANAEMIA IN PREGNANCY

Anaemia during pregnancy is responsible for 15% of maternal mortality. Early correction of anaemia avoids the need for transfusion and reduces maternal mortality. The decision for transfusion should not be made on the basis of haemoglobin estimation alone, as healthy and clinically stable women do not require blood transfusion even with Hb of <7 g/dl. To conclude, transfusion is necessary if Hb <6 g/dl and there are <4 weeks for delivery. When Hb is <7 g/dl in labour or in immediate postpartum period, blood transfusion is only indicated if there is previous history of bleeding or patient is prone for bleeding due to some medical condition. Transfusion is also indicated if Hb is 7 g/dl, for women with continued bleeding or at risk of further significant haemorrhage or for those presenting with severe symptoms that need immediate correction (cardiac decompensation).[3,4] Transfusion in patients with sickle disease and thalassaemia should only be reserved for severe situations because prophylactic transfusion is associated with increases in costs, number of hospitalizations, and the risk of alloimmunisation.[5]

OBSTETRIC HAEMORRHAGE

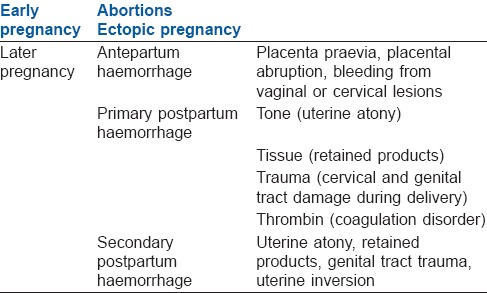

Obstetric haemorrhage continues to be the leading cause of maternal mortality, ranging from 13% in developed countries to 34% in Africa.[6] An obstetric haemorrhage may occur before or after delivery, but >80% of cases occur postpartum, responsible for 25% of the estimated 358,000 maternal deaths each year.[7] [Causes of obstetric haemorrhage are shown in Table 1]. Blood loss results in hypoxia, metabolic acidosis, ischaemia and tissue damage, resulting in eventual global organ dysfunction. Massive blood loss results in consumptive coagulopathy and this is difficult to distinguish from dilutional coagulopathy, caused by transfusion with packed red cells and crystalloids, which in turn is difficult to differentiate in the acute setting from DIC. Dilution impairs coagulation and leads to further blood loss. All soluble clotting factors are absent in packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and stored whole blood is deficient in platelets and factors V, VII and XI. Thrombocytopaenia is the most common defect found in women with blood loss and multiple transfusions.[8]

Table 1.

Causes of obstetric haemorrhage

ESTIMATION OF BLOOD LOSS

As earlier stressed, visual assessment of blood loss is “notoriously” inaccurate and clinicians can underestimate blood loss by 50%.[8] Standard definitions of postpartum haemorrhage, that is, >500 ml after vaginal delivery and >1000 ml after caesarean section, do not adequately reflect the clinical response of the patient. Definitions of massive haemorrhage vary and have limited value. It may arbitrarily be considered a situation where 1-1.5 blood volumes may need to be transfused acutely or in a 24-h period[9] where, normal blood volume in the adult is taken as approximately 7% of ideal body weight. Other definitions include 50% blood volume loss within 3-h or a rate of loss of 150 ml/min.

Immediate Hct will not reflect the actual blood loss. Even a blood loss of 1000 ml will reflect a fall in Hct of only 3% in the 1st h.[8] Urine output, on the other hand, being sensitive to changes in blood volume, can give an early indication of changes in renal perfusion and hence perfusion of other organs.[8] Pulse Oximetry is an imperfect tool in the haemodynamically unstable patient. Use of central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring alone in bleeding obstetric patients with haemodynamic instability[9] is not recommended because it is not a true surrogate of assessment of patient's intravascular status. CVP and its response to fluid challenge or noninvasive cardiac variables using ultrasound can be used for estimation of intravascular status and can guide fluid resuscitation in obstetrics patient with haemodynamic instability. Volumetric/flow bases fluid resuscitation is recommended when compared to pressure based methods. All sources agree that the decision to transfuse is a clinical decision taken on the basis of the individual patient's status.[9,10,11]

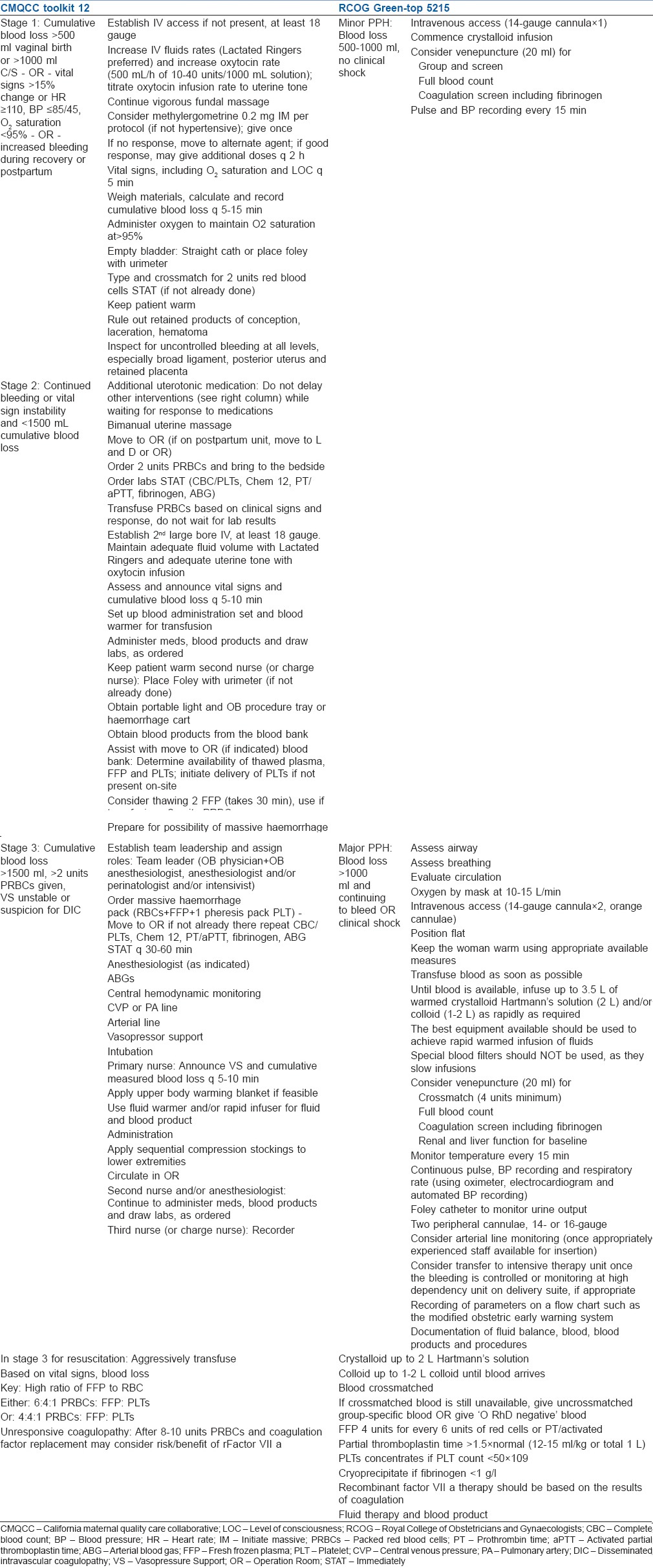

MANAGEMENT OF OBSTETRIC HAEMORRHAGE

Systems based on trauma protocols are increasingly being used to manage obstetric haemorrhage.[10] It is also accepted that a protocol-based, multidisciplinary approach to massive blood loss yields the best results.[7,10,11,12,13,14] A number of protocols for obstetric haemorrhage, particularly postpartum haemorrhage have been designed.[12,14,15] The CMQCC protocol, also adopted by the ACOG District 11, is a step-by-step checklist format, based on the staging of obstetric haemorrhage,[12] whereas the RCOG Green-Top Guideline No. 52 also lays out therapeutic and monitoring guidelines for minor and major postpartum haemorrhage.[14] While there are some individual variations, the broad outlines remain the same. Comparison of two commonly used protocols is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of two commonly used protocols

The mainstay of management of haemorrhage is rapid resuscitation with crystalloids to restore and maintain the circulating blood volume to prevent tissue and organ hypo-perfusion. Role of blood transfusion in acute haemorrhage is to maintain tissue oxygenation and reversal or prevention of coagulopathy using appropriate blood components. Prevention and treatment of hypothermia, acidosis and hypocalcaemia will ensure optimal function of transfused coagulation factors. Simultaneously, the cause of the bleeding should be identified and controlled, by medical means, surgery or invasive radiography.

CONTROVERSIES AND CONSENSUS FOR TRANSFUSION IN OBSTETRICS

The SAFE trial and the CRISTAL trial have shown colloids to have no advantage over crystalloids in the acute setting, and the high cost of colloids makes crystalloids the preferred resuscitative fluid in most centres.[15,16,17] It should be borne in mind that crystalloids rapidly equilibrate with the extracellular fluid, and only about 20% remains in the circulation after the 1st h. In previous studies it was suggested that, estimated blood loss should be replaced with about 3 times the volume of crystalloids[8] however, this concept has been challenged in recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) like SAFE trial, and starch trials and now, the accepted average ratio of colloid: Crystalloid is 1:1.5.

Whole blood or blood component?

Alexander et al., in an observational study of massive obstetric haemorrhage at Parkland hospital, showed whole blood to be superior to PRBCs or combined transfusions in preventing acute tubular necrosis and other complications.[18] The availability of fresh warm blood in developing countries could provide an alternative to more expensive and infrastructure-dependent blood components.[2] Whole blood replaces many coagulation factors, and its plasma expands blood volume. It has the added advantage of exposing the patient to fewer donors.

To cross-match or not to cross-match?

The chances of a clinically significant red cell antibody being missed in a patient with a negative antibody screen (false negative) are 1-4/10,000.[19,20] Given that the chance of adverse consequences is small, in cases of acute massive haemorrhage, it appears reasonable to transfuse blood without type-and-screened red blood cells.[8,12,13]

CONCERNS REGARDING KELL ANTIGEN AND CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

Haemolytic Disease of the Foetus and Newborn due to Kell antibodies is gaining in importance with the declining incidence of HDFN due to Rh incompatibility. Donor blood is not routinely tested for Kell antigen in most countries, though it is an NHS recommendation that Kell and Cytomegalovirus screening should be done for blood intended for pregnant women.[13]

O RH D NEGATIVE BLOOD TRANSFUSION

The NHS (National Health Service) recommends that the use of Rh negative red blood cells is mandatory in RhD negative patients with pregnancy, RhD negative females with child-bearing potential and in an emergency to premenopausal females of unknown blood group. If RhD positive red cells are given to a female of childbearing potential, consideration should be given to the use of anti-D immunoglobulin (plus exchange transfusion for large scale transfusion).[21] All major guidelines recommend the use of O RhD negative transfusion as a life-saving measure in women of unknown blood group, but only as a last resort, in order to conserve this rare resource.

BLOOD TRANSFUSION; HOW MUCH TO GIVE AND WHEN TO STOP?

Most protocols recommend maintaining a target Hct of 21-24%. Hébert et al. showed that restrictive transfusions and liberal transfusions were of equivalent value in critically ill patients while relatively stable patients undergoing liberal transfusions had a higher 30-day mortality.[22] The conclusive consensus form various protocols and guidelines suggest that the transfusion is rarely indicated in Hb >10 g/dl. If Hb is <6 g/dl transfusion is indicated irrespective of cause and condition of the patient. If Hb is between 6 and 10 g/dl, the indication will depend upon whether patients is actively bleeding or having history of previous excessive haemorrhage or having some medical condition where optimal Hb is >7 g/dl is required.[9,23] The common goals for transfusion in the obstetric patient[14] is to achieve

Haemoglobin >8 g/dl,

Platelet count >75 × 109/l,

Prothrombin time (PT) <1.5 × mean control,

Activated PT <1.5 × mean control and

Fibrinogen >1.0 g/l.

The risk of dilutional coagulopathy needs to be borne in mind when multiple units of PRBCs and crystalloids/colloids are used. Various recommendations for the proportions of blood components are in effect. While it has been observed that patients receiving <10 units of PRBCs rarely need component replacement, the lowest mortality occurs in the patients where ratio of plasma and PRBCs is 1:1. Both the CMQCC Toolkit and the RCOG Green top Guideline No 52 recommend a ratio of PRBC, fresh frozen plasma and Platelet of 6: 4:1 in cases of massive haemorrhage.[12,14]

ROLE OF RECOMBINANT FACTOR VIIA THERAPY

The role of rVII in primary postpartum haemorrhage is controversial because it may also result in life-threatening thrombosis.[24] When available, its use should be reserved for rescue therapy when conventional therapy has failed.[12,14] It is to be remembered that recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) will not work if there is hypofibrinogenemia, severe thrombocytopenia, acidosis and hypothermia. Therefore, fibrinogen should be above 1 g/l and platelets greater than 20 × 109/l before rFVIIa is given. If there is a suboptimal clinical response to rFVIIa, these should be checked and acted on before the second dose is given.[14] The normal recommended dose is 90 μg/kg[12]

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITHEXCESSIVE SURGICAL BLOOD LOSS

There are various techniques which can be used either in anticipation of surgical blood loss or used when there is excessive blood loss during surgery.

CELL SALVAGE IN OBSTETRICS

Cell salvage also known as intra-operative blood salvage (IBS) or intra-operative cell salvage is a technique in which patients own blood cells are re-transfused after separation from lost blood.[25] IBS has been used in ectopic pregnancies,[26] caesarean sections,[27] in vaginal deliveries and is acceptable under certain circumstances to Jehovah's witnesses.[27,28]

The safety of cell salvage has been questioned because of the risk of embolism and alloimmunisation. It is recommended that it be carried out in centres with the appropriate experience and adequate infrastructure.[14,26] However, Allam et al. in their review could not find a single maternal adverse effect directly related to cell salvage.[26]

PREOPERATIVE AUTOLOGOUS BLOOD DONATION IN OBSTETRICS

Early identification of patients at risk for obstetric haemorrhage and storage of autologous blood has been attempted - preoperative Autologous Blood Donation. Since most patients do not have an identifiable risk factor and many patients do not donate more than the unit of blood, its utility in acute severe haemorrhage is questionable. A study from a Nigerian teaching hospital showed it to be feasible in their Obstetrics and Gynaecology unit, and some authors recommend it as an option in developing countries.[2,29] However, others question its utility and safety as it may cause anaemia, does not eliminate transfusion risk, cannot be used in an emergency and is not acceptable to Jehovah's Witnesses.[29]

ROLE OF ANTIFIBRINOLYTIC THERAPY IN OBSTETRICS

Antifibrinolytics help in reduction of blood loss during obstetric surgery and other obstetric haemorrhage. Some studies have shown that tranexamic acid reduces postpartum haemorrhage.[30] A larger RCT of 15,000 subjects, the WOMAN trial, is now underway to test the efficacy of tranexamic acid.[31]

SUMMARY

Blood transfusion is an essential component of obstetric care and at times lifesaving. Inappropriate transfusions during pregnancy and the postpartum period expose the mother to the risk of HDFN. In the situation of obstetric haemorrhage early resuscitation is done with crystalloids and/or colloids with oxygenation while simultaneously taking all steps to control bleeding and reduce the transfusion requirement. A preplanned, multidisciplinary protocol yields the best results in the management. The decision to perform a blood transfusion should be made on both clinical and haematological grounds. The majority of protocols recommended that Hct be maintained minimally at 21-24%; however, in actively bleeding patient, target Hct should be 30%. To avoid dilutional coagulopathy, concurrent replacement with coagulation factors and platelets may be necessary. Whole blood may be preferred in acute massive haemorrhage, especially where blood components are not readily available. In an extreme situation and when the blood group is unknown, O RhD negative red cells should be given.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Obaid TA. No woman should die giving life. Lancet. 2007;370:1287–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schantz-Dunn J, M N. The use of blood in obstetrics and gynecology in the developing world. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4:86–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pena-Rosas JP, Viteri FE. Effects of routine oral iron supplementation with or without folic acid for women during pregnancy (Cochrane Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD004736. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004736.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reveiz L, Gyte GM, Cuervo LG. Treatments for iron-deficiency anaemia in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD003094. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003094.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koshy M, Burd L, Wallace D, Moawad A, Baron J. Prophylactic red-cell transfusions in pregnant patients with sickle cell disease. A randomized cooperative study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1447–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812013192204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: A systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367:1066–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLintock C, James AH. Obstetric hemorrhage. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1441–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY, et al. Obstetrical haemorrhage. In: Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY, et al., editors. Williams Obstetrics. 23rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. pp. 757–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas D, Wee M, Clyburn P, Walker I, Brohi K, et al. Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Blood transfusion and the anaesthetist: Management of massive haemorrhage. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:1153–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saule I, Hawkins N. Transfusion practice in major obstetric haemorrhage: Lessons from trauma. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez MC, Goodnough LT, Druzin M, Butwick AJ. Postpartum hemorrhage treated with a massive transfusion protocol at a tertiary obstetric center: A retrospective study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shields L, Lee R, Druzin M, McNulty J, Mason H. Blood product replacement: Obstetric haemorrhage. CMQCC Obstetric haemorrhage toolkit, Obstetric haemorrhage care guidelines and Compendium of best practices reviewed by CADPH-MCAH: 11/24/09. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.mail.ny.acog.org/website/Optimizing_Haemorrhage/Transfusion_Policy.pdf .

- 13.Rege K, Bamber J, Slack MC, Arulkumaran S, Cartwright P, Stainsby D, et al. Blood Transfusions in Obstetrics. RCOG Green Top Guidelines NO. 47. 2007. Dec, [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 10]. Minor revisions July 2008. Available from: http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog.corp/uploadedfiles/GT47BloodTransfusions1207amended.pdf .

- 14.Arulkumaran S, Mavrides E, Penney GC, Aberdeen Prevention and management of post-partum haemorrhage. RCOG Green-Top Guideline 52. 2009. May, [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.rcog.org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/prevention-and-management-postpartum-haemorrhage-green-top-52 .

- 15.Martel MJ, MacKinnon KJ, Arsenault MY, Bartellas E, Klein MC, Lane CA, et al. Hemorrhagic shock. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24:504–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annane D, Siami S, Jaber S, Martin C, Elatrous S, Declère AD, et al. Effects of fluid resuscitation with colloids vs crystalloids on mortality in critically ill patients presenting with hypovolemic shock: The CRISTAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1809–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, French J, Myburgh J, Norton R, et al. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2247–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander JM, Sarode R, McIntire DD, Burner JD, Leveno KJ. Whole blood in the management of hypovolemia due to obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1320–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a4b390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudhary R, Agarwal N. Safety of type and screen method compared to conventional antiglobulin crossmatch procedures for compatibility testing in Indian setting. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5:157–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.83243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boral LI, Hill SS, Apollon CJ, Folland A. The type and antibody screen, revisited. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979;71:578–81. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/71.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doughty H, Rowley M. Reviewers. Guidelines for the Use of Group O D Negative Red Cells Including Contingency Planning for Large Scale Emergencies by Stainsby and Murphy, 2003. National Blood Transfusion Committee. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, Marshall J, Martin C, Pagliarello G, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shander A, Gross I, Hill S, Javidroozi M, Sledge S. College of American Pathologists. A new perspective on best transfusion practices. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:193–202. doi: 10.2450/2012.0195-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connell KA, Wood JJ, Wise RP, Lozier JN, Braun MM. Thromboembolic adverse events after use of recombinant human coagulation factor VIIa. JAMA. 2006;295:293–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashworth A, Klein AA. Cell salvage as part of a blood conservation strategy in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:401–16. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allam J, Cox M, Yentis SM. Cell salvage in obstetrics. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2008;17:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiskopf RB. Erythrocyte salvage during cesarean section. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1519–22. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liumbruno GM, Liumbruno C, Rafanelli D. Autologous blood in obstetrics: Where are we going now? Blood Transfus. 2012;10:125–47. doi: 10.2450/2011.0010-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obed JY, Geidam AD, Reuben N. Autologous blood donation and transfusion in obstetrics and gynaecology at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital Maiduguri, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2010;13:139–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novikova N, Hofmeyr GJ. Tranexamic acid for preventing postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007872. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007872.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shakur H, Elbourne D, Gülmezoglu M, Alfirevic Z, Ronsmans C, Allen E, et al. The WOMAN Trial (World Maternal Antifibrinolytic Trial): Tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: An international randomised, double blind placebo controlled trial. Trials. 2010;11:40. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]