Abstract

This analysis summarizes trends in family economic well-being from five non-experimental, longitudinal welfare-to-work studies launched following the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA). The studies include a sizable group of parents and other caregivers who received TANF at the point of sample selection or shortly thereafter, and share a wide range of similar measures of economic well-being. This analysis provides descriptive information on how these families are faring over time. Our results confirm what has been found by previous studies. Many families remain dependent on public benefits, and are either poor or near-poor, despite gains in some indicators of economic well-being. We caution that these aggregate statistics may mask important heterogeneity among families.

U.S. welfare policy has a long history of expansion and retrenchment. One of the most significant developments since its inception in 1935, with the passage of the Social Security Act and creation of Aid to Dependent Children, manifested in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA). This federal law eliminated welfare as an entitlement benefit, and solidified a shift in welfare policy back to the states. In the wake of “welfare reform,” as PRWORA is often labeled, welfare caseloads dropped precipitously. However, as noted by many policy scholars, caseload reduction should not be heralded as the sole indicator of PRWORA’s success (Blank, 2002; Duncan & Chase-Lansdale, 2001; Zedlewski, 2002). Rather, it is important to understand whether this caseload decline has been accompanied by economic gains or losses, as well as changes in other indicators of family well-being.

This analysis summarizes trends in family economic well-being from several non-experimental, longitudinal welfare-to-work studies1 launched following the passage of PRWORA. Our set of indicators is limited primarily to those relating to economic well-being and hardship. We have done this deliberately so that the remaining papers in this issue may take up the question of how parents and children are faring in other domains.

The Illinois Families Study (IFS), the Women’s Employment Study (WES), the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FF), the Welfare, Children, and Families: Three-City Study (3-City), and the Milwaukee TANF Applicant Study (MTAS), although different in scope and purpose, all share key design elements. Each study was fielded at a similar time and includes a sizable group of parents and caregivers who received TANF at the point (or close to the point) of sample selection. All of these studies assessed well-being at multiple time points using similar measures. Because they are all non-experimental studies, none is able to conclusively demonstrate the causal impact of welfare reform on families. However, taken together, these studies provide important descriptive information about how families are faring in the wake of PRWORA.

We first provide a brief overview of the policy components of PRWORA, highlighting the state-specific characteristics of welfare reform policies that were implemented in Michigan (WES), Illinois (IFS and 3-City), Wisconsin (MTAS), Massachusetts (3-City), and Texas (3-City); the FF involves a cohort of infants born in 20 large urban areas.2 We next discuss factors that may have influenced welfare caseload declines during the mid to late 1990s, and as well as the state of the national economy during this time. Finally, we briefly review findings from various experimental and “leavers” studies, to provide further context for the results we present.

We compare the panel data from this group of studies to address the following questions:

What are the trends in employment, earnings, and income for former and current welfare recipients following the passage of PRWORA?

What are the trends in TANF receipt, and use of other government programs for this population?

What are the trends in other indicators of economic well-being?

Are there trends in family structure and composition?

Results from this synthesis task can inform future debates over PRWORA’s reauthorization and also serve as a contextual backdrop for the other articles in this special issue.

Federal Welfare Policy and the Economic Context: 1990–2005

Amid growing concern over the size and characteristics of the population receiving cash welfare in the U.S., and the growing cost of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA, P.L. 104–193) was signed into law. By replacing AFDC with Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), a time-limited welfare program that requires participation in work related activities as a condition for receiving cash assistance, PRWORA was intended to reduce dependence on government by promoting work, marriage, and self-sufficiency, and by discouraging out-of-wedlock births. The explicit goals of the TANF program, as stated in Section 401(a) of the Social Security Act, are to allow states the flexibility to create programs that:

“(1) provide assistance to needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives;

end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage;

prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies and establish annual numerical goals for preventing and reducing the incidence of these pregnancies; and

encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families” (Public Law 104–193).

It is important to note that, although policy analysts and scholars have suggested that reducing child poverty (or promoting child well-being) are implicit goals of TANF (e.g., Rector and Fagan, 2003), they are not explicit objectives of the law.

In accordance with PRWORA, states receive block grants to operate TANF programs, and have considerable discretion over these programs. At a minimum, programs must include work requirements and “work-trigger” time limits (set federally at 24 months, with an option for states to enact earlier triggers),3 lifetime limits for benefit receipt (set federally at a maximum of 60 months, although states may adopt shorter time limits, use their own funds to extend benefits beyond 60 months, and exempt up to 20 percent of their caseloads), and minimum levels of work participation rates among program participants. States have the option of implementing family caps and sanctioning recipients for noncompliance (see Committee on Ways and Means, 2004, for a more complete summary of PRWORA and the TANF program.) TANF was re-authorized by the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. Several of the original provisions have been revised, including definitions of allowable work activities, categories of exempted individuals, the computation of caseload reduction credits, and maintenance-of-effort requirements.

Although PRWORA has been credited with substantially changing the face of cash welfare assistance in the U.S., most of its major provisions can be traced back to state and federal initiatives over the decade preceding its passage. In particular, both the Family Support Act of 1988 (P.L. 100–485) and the state welfare waivers of the 1990s were precursors to PRWORA. The Family Support Act established the Job Opportunity and Basic Skill (JOBS) programs to promote education, training, and employment among welfare recipients in order to increase economic self-sufficiency. The welfare waivers of the 1990s granted states exemptions from federal AFDC program requirements in order to experiment with AFDC reforms, such as work requirements, time-limits on benefit receipt, and family caps.

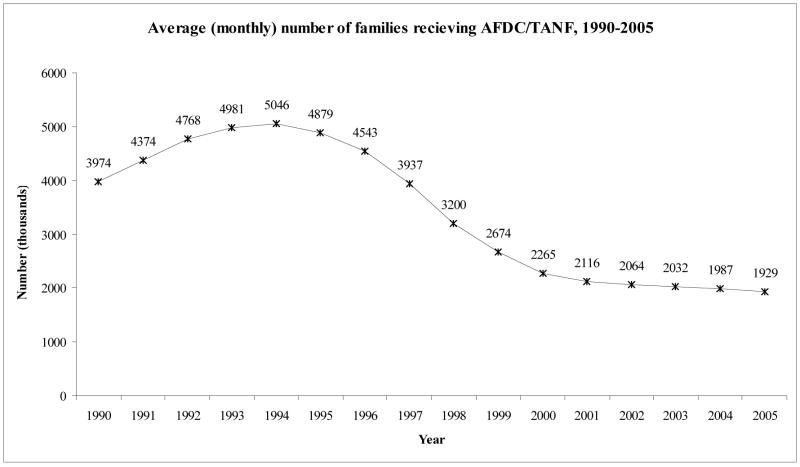

Taken together, the welfare reforms of the 1990s instituted significantly more stringent work requirements than previous welfare policy. This shift, along with a strong economy and expansions in work supports for low income families, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and child care subsidies, led to dramatic declines in welfare caseloads and increases in the employment of low income single-mothers during the latter half of the 1990s (Blank, 2002). As shown in Figure 1, the monthly average number of families on the AFDC caseload peaked in 1994 at slightly over 5 million, and declined thereafter. By 2005, the TANF caseload was just over 1.9 million families, representing a decline of about 51% since 1997, the first year in which TANF was implemented.

Figure 1. U.S. Welfare Caseload Trend.

Source: Data for 1990–2002 are from U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means (2004), Table 7-6. Data for 2003–2005 are from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Family Assistance (2006).

With the passage of PRWORA in 1996 and the strong economic period that followed this legislation, employment among single mothers increased considerably. The proportion of never married mothers (arguably the group most affected by welfare reform) who were working rose from 44% to 66% between 1993 and 2000. The percentage of all single mothers working grew from 58% to 75% during this time period. With the recession of 2001, however, this trend reversed. Sixty-two percent of never married mothers and 69% of all single mothers were working in 2005 (Haskins, 2006). Child poverty rates followed a similar pattern, decreasing from nearly 23% in 1993 to 16% in 2000, but rising again to 18% by 2005 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2006). Thus, despite declining welfare caseloads and increases in employment among single-mothers, more families with children appear to be experiencing economic stress in recent years (Loprest & Zedlewski, 2006).

Results from Experimental Evaluations and TANF Leaver Studies

Although caseloads plummeted after PRWORA was implemented, it is difficult to determine how much of this decline was due to welfare policies rather than economic conditions and other policy changes. Previous research has assessed the overall effects of welfare reform in two ways. First, researchers have turned to the experimental evaluations of “precursors” to the 1996 welfare reform by studying state welfare waivers and welfare employment programs implemented under the Job Opportunity and Basic Skill (JOBS) programs. Second, researchers have undertaken welfare “leaver” studies, which track welfare recipients after they leave TANF.4

Conducted during the mid-1990s, the experimental evaluation of the JOBS programs found that a key dimension of welfare reform policies, work requirements with sanctions for non-compliance, increased welfare recipients’ labor force participation (Grogger & Karoly, 2005; Hamilton et al., 2001). Over a five year period, welfare recipients who faced employment requirements and sanctions for non-compliance had earnings that were between $1,400 and $2,500 higher than the control group, who experienced AFDC rules. One reason that the welfare-to-work programs may not have had larger effects on participants’ earnings may have been the relatively high rates of employment in the control group. Indeed, the study found that between 66–88% of the control group was employed at some point during the five year study period. Program impacts on earnings were concentrated in the early years of the program, suggesting that these effects were due to welfare recipients’ entering the labor market more quickly than the control group. Over time, the employment rates and earnings of the experimental and control groups became more equivalent, although it is worth noting that the average annual earnings of both groups did not exceed $6,500.

Not surprisingly, given their impact on employment and earnings, work requirements and sanctions for non-compliance also affected welfare receipt. Estimates suggest that, on average, welfare recipients in the employment-based programs received between about $900 and $2,700 less in cash assistance than the control group counterparts (Hamilton et al., 2001). Thus, increases in their earnings were offset by decreases in welfare, such that the employment-based programs did not affect participants’ total income.

Evaluations of state welfare waivers of the early 1990s generally led to similar conclusions about the economic consequences of welfare reform policies, with two additional insights (Bloom & Michalopoulos, 2001; Grogger & Karoly, 2005). First, when states provide earnings supplements, typically through enhanced earnings disregards, the total incomes of recipients are likely to be significantly higher. That is, by allowing participants to work and continue to receive welfare, household incomes typically increase. Second, there is no evidence that time limits are linked with either better or worse economic outcomes, at least in the short-term (Bloom & Michalopoulos, 2001; Grogger & Karoly, 2006).

Another way to assess the economic consequences of welfare reform is by reviewing so-called “leaver” studies. These studies are descriptive, but provide a useful picture of how families are faring. Brauner’s and Loprest’s (1999) review of these studies finds that most TANF recipients who leave welfare are employed at some point in the following year, with estimates ranging from 68% to 88%. Rates of employment are lower, between 39% and 53%, among those who leave welfare because of sanctions for non-compliance.

Even relatively high rates of employment among welfare “leavers” do not translate into high earnings.Brauner’s and Loprest’s (1999) review found the average hourly wage of welfare recipients, the most common metric of earnings reported by leaver studies, ranged from $5.50 to $8.09 an hour. When average quarterly earnings were reported, they range from about $2,300 to $2,600 per quarter. With such low earnings, it is not surprising that a large majority of welfare leavers continue to rely on other forms of assistance, such as food stamps and Medicaid (Brauner & Loprest, 1999).

With fewer low-income mothers receiving cash welfare support, some scholars speculated about whether or not other forms of benefits might fill the void. For example, receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI)—cash support provided to low-income families with a disabled adult or child—might increase with declines in TANF receipt. Evaluations of the state welfare waivers implemented in the early 1990s suggest that SSI benefits increased in generosity relative to AFDC benefits and that as a result SSI receipt among single mothers may have increased (Garrett & Glied, 2000; Schmidt & Sedvak, 2004). However, PRWORA provisions also restricted SSI eligibility by excluding some previously eligible groups (e.g., non-citizens) and creating more restrictive definitions disability for other groups (e.g, children; Schmidt, 2004). Consequently, it is not clear whether families who are no longer eligible for TANF (or who are unable to comply with the conditions of TANF receipt) are more likely to seek assistance through the SSI program in the wake of PRWORA than in the years preceding this legislation. In any case, evidence from the leaver studies suggests that from 4% to 12% of former welfare recipients collect SSI benefits (Acs, Loprest & Roberts, 2001).

Welfare Reform Context in the States

To provide additional context for the findings presented below, we offer a brief description of the caseload trends in, and key welfare policy components adopted by, the states relevant to the studies profiled in this analysis. Peak welfare caseloads were reached in the early 1990s for the states relevant to WES, IFS, MTAS, and 3-City. Michigan’s and Wisconsin’s caseloads were highest in 1991 and 1992, respectively; Massachusetts’ and Texas’ caseloads were at their height in 1993; and Illinois’ caseload peaked in 1994. Each state’s caseload declined between its peak and March 2004 by more than 50%, with declines ranging from 58% in Massachusetts to 85% in Illinois (Crouse, Hauan, Isaacs, Swenson & Trivits, 2005).

Turning to the policy components, in 1994, Michigan began a welfare reform program called Work First, which encouraged recipients to find jobs quickly. This program became universal and mandatory for most welfare recipients in 1996. Overall, Michigan’s Work First welfare policy can be classified as having strict sanctions for women who do not comply with the requirement that all welfare recipients work 20 hours per week, with non-compliers facing a 25% reduction in benefits for four months, followed by the closure of their case (Seefeldt & Anderson, 2000). At the same time, average monthly cash assistance is more generous than in most other states (but has remained flat since 1993). Michigan is also relatively more generous than other states in allowing families to keep more of their cash assistance while working (Seefeldt, Pavetti, Maguire, & d Kirby, 1998).

Also in 1994, Illinois began a welfare-to-work program (“Work Pays”) that incorporated a mix of work incentives and sanctions. With the state’s TANF plan, a combination of work incentives and sanctions for non-compliance with welfare rules was carried forward. Under TANF, the state invests heavily in child care subsidies, has generous income disregards, and a “stopped clock” provision that suspends the time limit clock for single TANF recipients who are working at least 30 hours per week (in 2-parent families, one adult must work at least 35 hours per week). Yet, Illinois’ benefit levels are relatively low, the original state TANF plan included a “family cap” policy,5 and the state imposes a full-grant sanction for non-compliance with work requirements. Taken together, this policy mix offers a relatively balanced array of incentives and penalties.

Wisconsin began experimenting with its AFDC program in the late 1980s and implemented a total of eleven waiver-based welfare demonstrations.6 As a result, the state’s cash assistance caseload had already declined significantly by the time its TANF program, Wisconsin Works (W-2), was implemented in September 1997. Wisconsin Works exemplifies the work-first approach that many states adopted as part of welfare reform. Participants are expected to become employed as soon as they are able and are placed in one of four “tiers” based on an assessment of their employability. Those deemed to be “job ready” are can receive case management services and other work supports, including food stamps, child-care subsidies, and Medicaid, to help them become and remain employed, but no cash assistance.7 Those with significant barriers to employment may be eligible for a monthly cash grant, as well as food stamps, childcare subsidies and/or medical assistance, but are required to work in community service jobs or participate in other activities intended to prepare them for employment. Their grant does not depend on family size and can be reduced for every hour of assigned activity missed without “good cause.” Only custodial parents of newborns less 12 weeks old are exempt from the work requirement.

The welfare plan in Texas, which was a continuation of its previous federal waiver, is perhaps one of the more complicated in the country. Time limits for welfare receipt are relatively strict, and range from 12 months, for those considered job-ready, to 36 months, for those least prepared to work. Several exemptions apply, however, such as having any children who are less than school age. Earnings disregards are also complicated, becoming more restrictive every few months for entrants into employment. Texas also instituted immediate work requirements, including work orientation and job search programs. Benefit levels in Texas are also very low (e.g., set at 17% of the federal poverty line as of 1996). On the other hand, Texas did not implement a full family grant sanction or a family cap at the initiation of PRWORA, although the state later instituted full family sanctions for noncompliance with child support requirements.

Massachusetts was still operating under its HHS waiver when federal welfare reform was instituted. Under its plan, Massachusetts has a relatively strict time limit for cash assistance of 24-months in any 60-month period, albeit no lifetime limit. However, benefit levels are relatively high, and exemptions from work requirements are lenient (e.g., they include recipients with children under two years of age). In 1999, recipients with school-age children were required to work 20 hours per week, although over 50% of the caseload was exempt from the time limit or work requirements. The Massachusetts plan includes a full-family sanction, as well as a family cap.

The welfare policy context for FF is not detailed here, given that the FF study involves sites across 15 states representing a wide range of welfare reform policies.

Methods

The research design that characterizes each study in this special issue has been detailed elsewhere (Lewis et al., 2000; Piliavin, Dworsky, & Courtney, 2003; Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, and McLanahan, 2001; Winston et al., 1999; Danziger et al., 2000). However, we offer a brief overview of the five studies in terms of their key design elements.

All five of the highlighted studies share the following characteristics: they were implemented following the passage of PRWORA, they were non-experimental, they involved survey data collected at two or more time-points, their samples were randomly selected, and the original samples included TANF recipients or applicants who began receiving TANF. The WES and IFS studies involved random samples of active TANF caseloads in two different states. The FF and 3-City studies involved samples that were not exclusively comprised of TANF recipients. For these two studies, we identified a sub-sample of respondents who were receiving TANF at the point of their baseline interview, a strategy that has been used in other analyses comparing findings between studies (Moffitt & Winder, 2005). MTAS involved a TANF applicant sample. For the purpose of this exercise, a sub-sample of MTAS respondents was utilized—those who began receiving TANF within one month of their baseline interview. For this reason, the descriptive statistics presented in this analysis may differ from the descriptive statistics offered elsewhere for these three studies. Table 1 offers an overview of the study characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and survey field periods, by study

| Study | Sample or sub-sample N | Timing of survey waves | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | ||

| WES1 | 753 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | ||

| IFS2 | 1,363 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |||

| MTAS3 | 687 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | ||||

| FF4 | 1,447 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | ||||

| 3-City5 | 894 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |||||

Original sample drawn from the February 1997 TANF caseload in one urban Michigan county; sample size in table reflects all Wave 1 survey respondents (response rate 86%).

Original sample (N=1,899) drawn from the September, October, and November 1998 TANF caseloads in nine Illinois counties, representing approximately three-quarters of the state’s welfare population; sample size in table reflects all Wave 1 survey respondents (response rate 72%).

Original sample included 1,075 TANF applicants (a 98% response rate) who applied for TANF assistance in 1999 in Milwaukee County; sample size reflected in table represents all Wave 1 survey respondents who received TANF assistance within one month of their application.

Original sample included 4,898 mothers (86% participation rate) who gave birth to a focal child in an urban hospital setting during the period 1998–2000; sample size in table reflects all mothers who were receiving TANF and/or Food Stamps. (Note: it was not possible to distinguish between TANF and Food Stamp recipients in the baseline FF survey; as a result, the sub-sample used for this analysis may include some respondents who received only Food Stamps in Wave 1). The FF survey waves each spanned two years. The year representing the start of each survey field period is presented in the table. Both Wave 1 and Wave 2 were fielded during 1999 and 2000 (in different cities) and Waves 2 and 3 were fielded in 2001.

Original sample included approximately 2,400 low-income families (74% response rate) residing in Boston, Chicago, or San Antonio in 1999; sample size in table reflects the number of Wave 1 respondents who were receiving TANF at that point.

Analysis

For this analysis, researchers affiliated with each study were asked to calculate descriptive statistics across a range of demographic and socioeconomic indicators common8 to the five studies. For many of the studies, these statistics were weighted to adjust for baseline sample design elements (e.g., stratification), and for initial non-response and attrition in follow-up surveys.9 Table 2 presents the sample demographic characteristics for each study.

Table 2.

Wave 1 sample demographics, by study

| WES | IFS | MTAS | FF | 3-City | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity: | |||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 54% | 78% | 73% | 60% | 48% |

| Non-Hispanic white | 42% | 8% | 13% | 14% | 4% |

| Hispanic | 0% | 12% | 11% | 23% | 47% |

| Other race/ethnicity | 3% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 1% |

| Male respondent | 0% | 4% | 3% | 0% | 0% |

| Respondent mean age | 29.8 | 31.7 | 28.6 | 23.8 | 31.2 |

| Mean age of youngest child | 4.9 | 5.3 | 4.3 | <1 | NA |

| Mean age at first child’s birth | 19.5 | 19.9 | 20.4 | 19.6 | NA |

| High school or GED | 70% | 59% | 44% | 55% | 25% |

| Married | 10% | 11% | 4% | 7% | 21% |

| Average number of children < | |||||

| 18 years of age | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.5 |

NA=Not available.

Several differences in the sample characteristics are worth noting. The samples differ in racial and ethnic composition, reflecting, in part, the geographic variation in the studies. There are also differences due to sample design. For example, the FF study involved families with younger children and younger survey respondents because births (primarily to unmarried mothers) were sampled. Rates of marriage are highest for the 3-City Study, and rates of having at least a high school education (or its equivalent) are lowest for this study. 3-City respondents also have more minor-aged children, and WES, IFS, and FF respondents have higher levels of education, on average. Given the differences in the initial sample characteristics, we caution readers that it is unwise to make cross-study comparisons of the point estimates for the variables we explore. Instead, we focus our discussion on comparing general time trends across studies.

Table 3 presents trends in employment, wages, and household income-to-needs ratios for each study. In general, these data suggest relatively stable or increasing rates of full-time employment over the course of the studies.10 The increase in full-time employment between Wave 1 and Wave 2 for the FF study is expected, given the sample design (i.e., mothers of newborn infants who may have left or remained out of the labor force around the time of the child’s birth). A similar increase is observed for MTAS and 3-City—both groups had low initial levels of employment, as they were applying for or receiving TANF during the first wave of the survey, and likely faced immediate work or “work-like” activity requirements. For WES and IFS, the initial surveys were conducted several months after the TANF sample was selected, and thus higher initial employment rates, lower TANF receipt rates, and relatively smaller gains in employment over time reflect this design element. Nevertheless, not only does full-time employment appear to increase or stay relatively stable within each sample, but average hourly wages (indexed to 2003) also increase within every study sample. Average weekly or monthly earnings also increase within each study (results not shown).

Table 3.

Descriptive trends in employment, wages, and income-to-needs, by study

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed 35+ hours per week | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 30% | 41% | 45% | 44% | 43% | ||

| IFS | 28% | 31% | 29% | 29% | |||

| MTAS | 5% | 38% | 32% | ||||

| FF1 | 16% | 32% | 38% | ||||

| 3-City | 5% | 25% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Hourly wage (indexed to 2003) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | $7.51 | $7.93 | $8.16 | $8.69 | $9.04 | ||

| IFS | $8.17 | $8.91 | $10.03 | $9.35 | |||

| MTAS | $7.75 | $9.00 | $9.12 | ||||

| FF | $7.95 | $9.80 | $10.06 | ||||

| 3-City | $8.31 | $9.10 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Income-to-needs ratio | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 0.99 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.21 | 1.35 | ||

| IFS | 0.57 | 0.79 | 1.06 | 1.09 | |||

| MTAS | NA | 0.64 | 0.72 | ||||

| FF | NA | 0.87 | 1.00 | ||||

| 3-City | 0.74 | 0.81 | |||||

NA = Not available.

The percentage of FF mothers with full-time employment presented in Table 3 captures employment within three months of giving birth; however, 38% of mothers worked full-time for some duration during the year prior to their child’s birth.

As depicted in Table 3, the ratio of household income to family size adjusted to the federal poverty threshold (i.e., a ratio of 1.0 means that household income is situated on the federal poverty line for a family of a given size), indicates that, on average, families appear to be slowly climbing out of poverty. However, despite increases in family income-to-need, most of these families continue to live in or near poverty.

Table 4 presents the percentage of respondents who received benefits, income transfers, or material assistance from other programs, community charities or emergency services. All studies reveal declines in TANF receipt, ranging from 35 to 53 percentage points between the initial survey wave and the most recent survey wave. WES and IFS—the two studies that involved samples from TANF caseloads—have the lowest receipt rates by the end of their study field periods, although these two studies also include the most recent survey waves.

Table 4.

Descriptive trends in benefit receipt and transfers, by study

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TANF | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES1 | 74% | 48% | 30% | 25% | 21% | ||

| IFS1 | 52% | 31% | 19% | 11% | |||

| MTAS2 | 100% | 81% | 51% | ||||

| FF2 | 100% | 70% | 65% | ||||

| 3-City2 | 100% | 57% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Food Stamps | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 83% | 69% | 52% | 53% | 54% | ||

| IFS | 65% | 66% | 65% | 67% | |||

| MTAS | 90% | 85% | 80% | ||||

| FF | NA | 67% | 64% | ||||

| 3-City | 85% | 72% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Health insurance (respondent) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 93% | 84% | 76% | 79% | 81% | ||

| IFS | 81% | 75% | 80% | 82% | |||

| MTAS | NA | 88% | 92% | ||||

| FF3 | NA | 70% | 75% | ||||

| 3-City | 77% | 78% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Supplemental Security Income (respondent or child) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 1% | 3% | 4% | 6% | 6% | ||

| IFS | 10% | 11% | 11% | 14% | |||

| MTAS | 10% | 9% | 10% | ||||

| FF | NA | 5% | 7% | ||||

| 3-City | 21% | 24% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Earned Income Tax Credit | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | NA | 51% | 58% | 57% | 51% | ||

| IFS | 38% | 52% | 55% | 54% | |||

| MTAS | 41% | 38% | 46% | ||||

| FF | NA | 32% | 45% | ||||

| 3-City | 24% | 50% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Charity/emergency assistance | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 39% | 34% | 33% | 30% | 31% | ||

| IFS | 19% | NA | 17% | 15% | |||

| MTAS | 37% | 34% | 34% | ||||

| FF | NA | 13% | 14% | ||||

| 3-City | 9% | 5% | |||||

NA=Not Available.

WES and IFS both had samples that were randomly selected from TANF caseloads in early 1997 and late 1998, respectively. Although 100% of sample members were receiving TANF at the point of sample selection, some sample members were no longer receiving TANF at the point of their Wave 1 survey interview.

MTAS, FF, and 3-City studies all had original samples that included TANF recipients and non-recipients. For the purpose of this exercise, these three studies were asked to constrain their samples to include only TANF recipients, assessed at the point of the Wave 1 interview (FF and 3-City) or within one month of that interview (MTAS). The FF Study was not able to distinguish TANF from Food Stamp receipt in Wave 1, so the FF estimate of TANF receipt may include some respondents who only received Food Stamps.

Nearly all of the mothers reported having health insurance coverage for the delivery of their child in Wave 1; however this estimate did not distinguish between mothers who had general health insurance coverage and mothers who received coverage only for their child’s hospital delivery. The estimates for health care coverage in Wave 2 and 3 reflect the general health insurance status of the FF mothers.

With one exception (WES), each study provides evidence of increases in respondent reports of EITC receipt. This is true for SSI, to a lesser extent, across all studies except MTAS. Food Stamp receipt declined in all studies, with the exception of IFS. There is some evidence to suggest that the health insurance coverage for survey respondents increased over time, although it may be more accurate to say that coverage remained relatively stable since most increases are negligible and changes occur in both directions over time. With respect to charity or emergency assistance, most studies indicate a decline over time. Only the FF study shows an increase in such assistance, and this increase is just one percentage point.

Although Table 3 indicates that income-to-needs ratios appear to be increasing, this indicator of poverty has been widely criticized for a number of reasons and may not fully capture family economic well-being (Citro & Michael, 1995; Ruggles, 1990). Another method of gauging economic well-being is to assess the incidence of various hardships experienced by families (Beverly, 2001; Cancian & Meyer, 2004). Table 5 presents the proportion of each study sample that experienced hardships with housing, food, and unmet health care needs across survey waves.

Table 5.

Descriptive trends for other indicators of economic well-being, by study

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing hardship | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 19% | 17% | 17% | 15% | 19% | ||

| IFS | 20% | 19% | 10% | 11% | |||

| MTAS | 66% | 68% | 70% | ||||

| FF | NA | 48% | 55% | ||||

| 3-City | 6% | 3% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Food hardship | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 25% | 23% | 23% | 17% | 19% | ||

| IFS | 34% | 33% | 26% | 34% | |||

| MTAS | NA | 54% | 52% | ||||

| FF | NA | 7% | NA | ||||

| 3-City | 17% | 10% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Unmet health care needs | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | NA | NA | 29% | 32% | 33% | ||

| IFS | 22% | 19% | 14% | 15% | |||

| MTAS | 18% | 12% | 13% | ||||

| FF | NA | 6% | 8% | ||||

| 3-City | 11% | 8% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Positive perception of economic well-being | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 27% | 40% | 47% | 45% | 41% | ||

| IFS | 61% | 67% | 64% | 64% | |||

| MTAS | NA | NA | 63% | ||||

| FF | 78% | NA | 63% | ||||

| 3-City | 71% | 76% | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Reside with extended family | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| WES | 10% | 14% | 17% | 19% | 20% | ||

| IFS | 7% | 4% | 5% | 5% | |||

| MTAS | 24% | 18% | 13% | ||||

| FF | 27% | 20% | 14% | ||||

| 3-City | 41% | 31% | |||||

NA=Not Available.

Studies do not have identical measures of these hardships. The indicators of housing hardship varied across studies, ranging from being “forced to move from a residence or home because you could not afford the rent or mortgage” to broader composite measures that include homelessness, utility shut-offs, doubled-up families, and reports of being unable to pay full rent or mortgage payments in one or more months in the past year. Food hardship was also measured in different ways, including high scores on food insecurity or insufficiency scales, and single item assessments of whether a respondent or her children went hungry in the past 12 months. Unmet health care needs were assessed more consistently across studies using respondent reports of health care needs for self or children that were unmet due to the out-of-pocket cost (WES, IFS, FF, 3-City), or unmet for any reason (MTAS). Details on these measures can be found in Appendix B.

Appendix B.

Variable Definitions

| WES | IFS | MTAS | FF | 3-City | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-time work | Currently working full time (35+ hrs/wk) on all jobs, combined. | Currently working full time (35+ hrs/wk) on all jobs, combined. | Currently working full time (35+ hrs/wk) on all jobs, combined. | Worked 35+ hrs last week. At wave 1, measure represents full-time work status within the last 3 months (given that mother recently gave birth to child). | Currently working full time (35+ hrs/wk) on all jobs, combined. |

| Hourly wage | Hourly wage on current or most recent job before taxes and other deductions. Values lower than $2.00 per hour or greater than $50.00 per hour are excluded. | Hourly wage on current main job before taxes and other deductions. Values greater than $50 per hour are excluded. | Hourly wage on current job before taxes and other deductions. | Hourly wage before taxes and other deductions. Presumes8 hour work day and 52 week work year for mothers reporting daily/yearly wages. | Hourly wage on current main job before taxes and other deductions. |

| Income-to-needs ratio | Monthly income-to-needs (net of taxes)ratio is created by dividing respondent’s monthly household income by the monthly poverty threshold for respondent’s household size. Respondent’s monthly household income is the sum of respondent’s earnings last month, other household earnings last month, FIP (i.e., TANF) support last month, Food Stamps last month, SSI last month, child support last month, monetary transfers from family/friends outside respondent’s household last month, unemployment or workers compensation last month, and other household income last month, and subtracts monthly taxes, which consists of monthly federal income tax for the tax unit plus monthly payroll tax for all household members. | Monthly income-to- needs ratio is created by dividing respondent’s annual gross household (i.e., respondent, cohabiting partner, and dependent co-resident children) income from the previous calendar year by the poverty threshold for respondent’s household size at the previous interview. (For wave 1, the current household size was used, minus any dependent children who were born, or a spouse/partner who moved in, within the last year.) Respondent’s household income is the sum of earnings, TANF, Food Stamps, SSI, child support, pensions, social security benefits, unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, foster care payments, emergency assistance, money from family or friends, and all other sources combined. For respondents who reported an income range (in increments of $2,500) rather than a specific value, the median value of the range was used. | Annual income-to-needs ratio computed by dividing gross household income for the past 12 months by the family- size adjusted poverty threshold. Household income is the sum of TANF payments, food stamp benefits, earnings reported for the purpose of Unemployment Insurance, income from other government programs, and spouse/partner earnings (if applicable).The first three income sources were measured using administrative data; the latter two were measured using survey data. | Yearly self-reported total gross household income divided by the poverty threshold for the household size/composition. For respondents who reported income ranges, hotdeck imputation was used. Respondents with no income information were left missing. Wave 1 generated only income ranges and substantial missing values, so no income-to-needs ratio is included for that wave. | Monthly income-to- needs ratio is created by dividing respondent’s annual gross household (i.e., from all individuals contributing to the household finances) income from the previous calendar year by the poverty threshold for respondent’s household size at the previous interview. (For wave 1, the current household size was used, minus any dependent children who were born, or a spouse/partner who moved in, within the last year.) Respondent’s household income is the sum of earnings, TANF, Food Stamps, SSI, child support, pensions, social security benefits, unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, foster care payments, emergency assistance, money from family or friends, and all other sources combined. For respondents who reported an income range (in increments of $2,500) rather than a specific value, the median value of the range was used. |

| TANF | Respondent’s household received cash TANF benefits last month (administrative data). | Respondent currently receives cash TANF benefits for self and/or dependent children (self-report). | Open TANF case, within 30 days of baseline interview or at the time of the follow-up interviews, as measured using administrative data | At waves 2 and 3, received TANF in past 12 months. At wave 1, received TANF or Food Stamps in past 12 months. | Respondent currently receives cash TANF benefits for self and/or dependent children (self- report). |

| Food Stamps | Respondent or someone in respondent’s household received food stamps, food stamps on the Bridge Card, or Food Stamp cashout in the prior month (self-report). | Respondent currently receives Food Stamp benefits for self and/or dependent children (self-report). | Open Food Stamp case, within 30 days of baseline interview or at the time of the follow-up interviews, as measured using administrative data | At wave 2 and 3, received Food Stamps in past 12 months. | Respondent currently receives Food Stamp benefits for self and/or dependent children (self- report). |

| Health insurance status | In waves 1 and 3, a respondent is coded as receiving some form of health insurance if she receives (1) Private or employer provided health insurance, or (2) Medicaid, Medicare, or any other health insurance. In wave 2, a respondent is coded as having health insurance if she reports receiving (1) Medicaid or Medicare, or (2) any other health insurance coverage. In waves 4 and 5, a respondent is coded as receiving some form of health insurance if she receives (1) Medicaid, Medicare, or any other government health insurance, (2) any health insurance plan through current employer, former employer, or union, or(3) health plan through someone else, military health plans, or plans bought on her own through a health insurance agency. | Respondent reported being “covered by a health insurance plan right now.” | Respondents were asked: “Do you have medical insurance coverage now?” | At waves 2 and 3, respondent is currently covered by Medicaid (or other public insurance that pays for medical care) or private insurance. At wave 1, mother was asked how she is paying for child’s birth, and nearly all mothers reported some form of insurance. | A respondent is coded as receiving some form of health insurance if she answered “yes”+G8 to “Are you covered by any type of health insurance plan or program that pays for at least some of your medical expenses?” |

| Supplemental Security Income | In waves 2-5, respondents were asked: “Are you currently receiving disability benefits for yourself?” Respondents who answered “yes” are coded as receiving disability benefits. This question was not asked in wave 1; values for wave 1 are imputed from related survey questions and administrative data. | Respondents were asked if they received “money or assistance from Aid for the disabled (such as Supplementary Security Income or SSI)” for themselves in the previous calendar year. | Respondents were asked “Have you or any other members of your family received Supplemental Security Income or SSI benefits at any time since we last interviewed you? Which family member or members received SSI benefits?” SSI benefits for self or any children are counted. | At waves 2 and 3, respondents were asked if they or child receives SSI. | Respondents were asked if they or their child were receiving “help from the Supplemental Security Income program, called SSI?” Respondents who anwersed “yes” were considered to have received SSI. |

| Earned Income Tax Credit | Respondents were asked if they had received a tax refund. If they reported that they had, they were then asked, “Did you receive the Earned Income Tax Credit?” Those who responded yes are listed as having received the EITC. Since many respondents might receive the EITC as part of their refund and not realize the difference between the EITC and other tax provisions, this variable should be considered “perceived receipt of EITC.” | Respondents were asked if they received the Earned Income Tax Credit for employment in the previous year. If they answered “yes” then respondent was considered to have received EITC. | Did your family receive any money from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) since we last interviewed you? | At waves 2 and 3, respondents were asked if as part of filing tax return they had filled out form to claim the EIC. | Respondents were asked if they had filed a tax return last year. If they reported that they had, they were then asked, “The federal government allows parents who have jobs which pay less than about $25,000 a year to pay lower taxes. This special rule is called the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, and is available to families with children. Did you use this on your federal income tax return last year?” Those who responded yes are listed as having received the EITC. |

| Charity/emergency assistance | “Many people need some kind of help for food or shelter from private charities, community groups like churches, soup kitchens, or place like that. Since (previous interview date) how often have you sought or received help from any of these groups or places - once a week or more, a few times a month, a few times a year, or never?” Respondents were coded as receiving charity/emergency assistance unless they answered “never.” | Respondents were asked: “Since your last interview” (or, for wave 1, in the past year), “has there been a time when you went to a church or charity for clothes or help with a financial problem?” Respondents were also asked: “Since your last interview” (or, for wave 1, in the past year), “about how many times have you used a food pantry or soup kitchen because of a shortage of food or money?” Response options included “never,” “once or twice,” “3 to 5 times,” “6 to 10 times,” “11 to 20 times,” and “more than 20 times.” Respondents who answered “yes” to the first question or who answered more than “once or twice” to the second question were considered to have received charity and emergency assistance. | Respondent answered “yes” to any of the following questions: Wave 1: Have you and your family received help in the form of money or other goods like food or clothing from churches, community? Wave 2: Has your family received money from churches, neighborhood centers or community agencies at any time since the last interview? Has your family received other goods like food or clothing from churches, neighborhood centers or community agencies, including any help you received from food pantries, at any time since the last interview? Wave 3: Did food pantries, churches, community agencies, or neighborhood centers ever give you food to feed your family since we last interviewed you? Did churches, community agencies, or neighborhood centers ever give you or your children clothes to wear since we last interviewed you? Did churches, community agencies, or neighborhood centers ever provide a place for your family to stay since we last interviewed you? Has your family received any money from churches, community agencies, or neighborhood centers since we last interviewed you, including money that was used to pay for your rent or an electric, heating or telephone bill? | At waves 2 and 3, respondent reported receiving free food or meals in past 12 months because there wasn’t enough money. | Respondents were asked two questions: “Have you or your child received free clothing from a church or other organization in the past 30 days?” and Have you or your child received emergency food from a church, food pantry, or food bank in the past 30 days?” Respondents who answered “yes” to either question were considered to have received charity and emergency assistance. |

| Housing hardship | Respondents were asked “Has your gas or electricity been turned off since (last interview date) because you couldn’t afford to pay the bill?”; “Have you been evicted since (last interview date)?” and; Have you ever been homeless since (last interview date)? “Housing hardship” is coded “1” if a respondent answers “yes” to any one of these three items. | Respondents were asked: “Since your last interview” (or for wave 1, in the past year), “has there been a time when you had service turned off by the gas or electric company, or the oil company wouldn’t deliver oil because payments were not made?”; “Since your last interview” (or for wave 1, in the past year), “has there been a time when you were evicted from your home or apartment for not paying the rent or mortgage?”; “Since your last interview” (or for wave 1, in the past year), “has there been a period of more than 2 days that you: (1) stayed at a homeless shelter or domestic violence shelter, (2) lived in a care or other vehicle, (3) lived in an abandoned building, (4) lived “on the streets,” and (5) stayed with a friend or relative for less than 2 weeks because you had nowhere else to go?” Respondents who responded “yes” to any of these items were considered to experience housing hardship. | Was there ever a time (during the past 12 months/since the last interview) when (1) you could not pay your rent or mortgage because you did not have enough money; (2) you were evicted or lost your house because you did not have enough money to pay the rent or mortgage; (3) your telephone service was shut off because you did not have enough money to pay your bill; (4) your gas or electricity was shut off because you did not have enough money to pay your bill; (5) you were homeless (i.e., living in any of the following places: in a homeless shelter, a motel room, on the streets, in a car or other vehicle, in an abandoned building, or at a camping ground); or (6) you and your child(ren) moved in with family or friends because you had no other place to live? | At waves 2 and 3, respondent reported that could not pay full amount of rent, mortgage, gas, oil or electricity bills; or were evicted or had gas/electric or phone turned off because of non-payment; moved in with others because of financial problems; stayed in a shelter or other place not meant for regular housing for at least one night. | Respondents were asked “In the past 2 years, were you forced to move from a residence or home because you could not afford the rent or mortgage?” Caregivers who responded “yes” were considered to have experienced housing hardship. |

| Food hardship | Respondents were asked “Which of these statements best describes the food eaten in your household in the last 12 months: enough to eat, sometimes not enough to eat, often not enough to eat.” If a respondent answered “sometimes” or “often” not enough to eat, she was coded as having a food insufficiency problem. | The food hardship variable was created using 5 items from the USDA food security scale: (e.g., “In the past year, how often did you cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn’t enough money for food?”). If respondents answered “sometimes” or “often” to any of the five items, then the respondent was coded as experiencing food hardship. | Food hardship was assessed using fifteen of the eighteen items that comprise the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) measure of food insecurity. Study participants who responded affirmatively to three or more of the items were counted as food insecure. | At wave 2, respondent reported that self or child/ren went hungry because there wasn’t enough money. | The food hardship variable was created using 7 items from the USDA food security scale: (e.g., “In the past year, how often did you cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn’t enough money for food?”). If respondents answered affirmatively to any of the 7 items, then the respondent was coded as experiencing food hardship. |

| Unmet health care needs | Respondents were asked “Was there any time since (last interview date) that you needed to see a doctor or dentist but could not afford to go?” If a respondent answered “yes” to this question she was considered to have unmet health care needs. | Respondents were asked: “Since your last interview” (or, for wave 1, in the past year), “has there been a time when you or your children (1) needed to see a doctor or go to the hospital but couldn’t afford to; (2) needed to fill a prescription for medicine but couldn’t afford to fill it; or (3) needed to see a dentist but couldn’t afford to go?” If respondent answered “yes” to any of these items, then the respondent was considered to have unmet health care needs. | Has there ever been a time (during the past 12 months/since the last interview) when (focal child) did not get medical care when you thought she/he needed it? Has there ever been a time (during the past 12 months/since the last interview) when you did not get medical care when you thought you needed it? | At waves 2 and 3, respondent reported that someone in household did not go to doctor or hospital because they could not afford it. | Respondents were asked “In the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed medical care but did not get it because you could not afford it?” “In the past 12 months, was there any time when (child) needed medical care but did not get it because you could not afford it?” If a respondent answered “yes” to either of these questions, she was considered to have unmet health care needs. |

| Perceived economic well-being | Respondents were asked “How difficult is it for you to live on your total household income right now? If a respondent answered “not difficult” or “a little difficult” she was considered to perceive her economic well- being as good.” | Respondent were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statement. “These days I can generally afford to buy the things we need.” If respondent answered “somewhat agree,” or “strongly agree.” Then, they were considered to perceive their economic well-being as good. | Respondent describes family’s current financial situation as either “has just enough money to meet your basic needs” or “has enough money to meet your basic needs as well as a little extra.” | At wave 1, respondent reported having “just enough” money or “some left over” at the end of the month. At wave 3, respondent reported cutting back on clothes for self because there wasn’t enough money. | Respondents were asked the following statement. “Thinking about the end of each month over the past 12 months, did your up with?” Answers of “More than enough left over” or Some money left over” were considered to perceive “good” economic well- being. |

| Resides with extended family | Whether respondent’s mother or father is present in the household. | Respondents were asked to report all individuals who resided with them in their current residence at each survey wave. Respondents also reported their relationship to each household member. Respondents who reported living with their parent were coded as residing with extended family. | What is your current housing situation? Respondent answered “living in a house or apartment that a relative or friend rents or owns.” | Respondent reported that own or spouse/partner’s mother or father resided with them. | Respondents were asked to report all individuals who resided with them in their current residence at each survey wave. Respondents also reported their relationship to each household member. Respondents who reported living with their natural parent, adoptive parent, step-parent, foster parent, natural sibling, adoptive sibling, step-sibling, foster sibling, brother/sister-in- law, maternal grandparent, paternal grandparent, grandchild, aunt/uncle, niece/nephew, cousin, or other blood relative were coded as residing with extended family. |

Looking across these studies, there appears to be little consistency in the trends for housing, food, or health care hardship. However, respondents from most studies report increases in perceived economic well-being in several waves, although declines are also observed. Although not necessarily an indicator of hardship, per se, we also present estimates of the percentage of survey respondents in each study who report residing with extended family. In general, this trend declines over time (with the exception of the WES).

We also used descriptive data to explore whether there have been changes in family structure over time within each study sample. Since the goals of PRWORA emphasize “out-of-wedlock” birth and marriage, we looked specifically at the rates of birth, marriage, and cohabitation with an unmarried partner. No consistent trend across studies was evident for births or for cohabitation. Both MTAS and 3-City studies showed an increased rate of births; birth rates were relatively stable in the WES and IFS; and the FF study, given its birth cohort design, witnessed a precipitous drop in births between the first and second survey interviews, but an increase in births by the third survey interview.

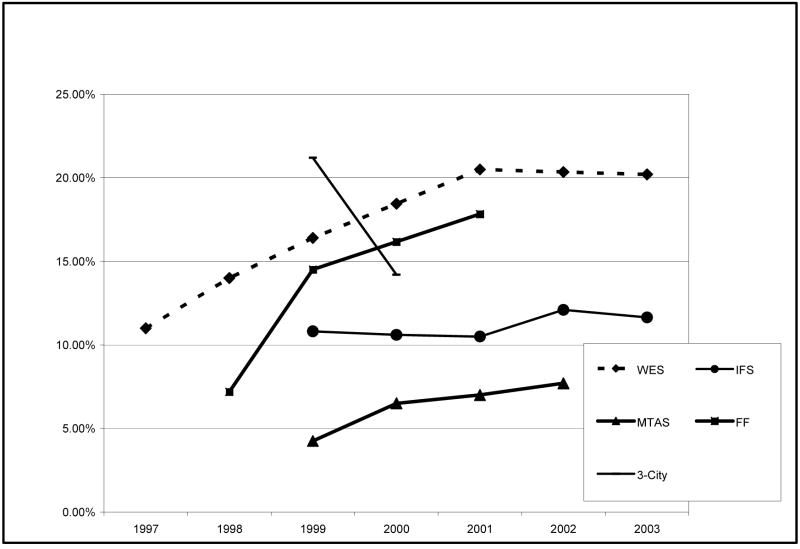

Cohabitation trends, similar to births, were inconsistent across studies. These rates fluctuated over time for WES, IFS, and MTAS, declined for the FF Study, and increased in the 3-City Study. However, with the exception of the 3-City Study (which had the highest marriage rate to begin with), rates of marriage increased across studies. Figure 2 shows the percentage of sample members who were married at each survey interview.11 For the IFS and MTAS, these increases are negligible; but for WES and FF, the increases in the percentage of sample respondents who report being married are larger.

Figure 2.

Marriage rates, by study

Discussion

This analysis has several limitations that should be kept in mind when considering the findings and their policy implications. First, the figures we present are merely descriptive, and cannot be interpreted as effects of welfare reform. To this end, we did not test whether changes over time were statistically significant. Rather, our goal was to assess whether general patterns could be observed across studies, providing a picture of how families are faring the wake of welfare reform. Furthermore, several of the measures we use are crude. In order to use comparable measures across the studies, it was sometimes necessary to dichotomize scales and simplify measures.

Another important caveat is that not every panel study involved a cross-sectional sample of TANF recipients. MTAS targeted TANF applicants (regardless of subsequent receipt) and both 3-City and FF targeted low-income families, and thus did not select their samples from the active welfare rolls (as did WES and IFS). In order to assess whether there were general patterns across studies, MTAS, FF, and 3-City samples were constrained to only those respondents who were receiving TANF at the point of the baseline interview or within one month of their TANF application. It is not known whether such subgroups are representative of the cross-sectional welfare recipient population in each study’s region(s).

It is also important to recognize that the within-study trends observed in the above tables and figures may be influenced by changes in sample composition stemming from attrition. Although weights and analyses were employed in all studies to address attrition, this strategy does not completely solve potential bias related to selection issues. Comparing statistics and trends across studies is also problematic, given that the original sampling strategies and sample characteristics differed for each study. Thus, the data we present should not be used to argue that one study sample fared worse or better than another study sample on any of the outcomes we assessed. Observed trends may also simply reflect the influence of aging cohorts.

A final caveat is that the trends depicted in each table involve aggregated (within-study) data, which may mask instability in any given indicator for individual respondents or families. For example, trends in full-time employment depicted in Table 3 give the impression that employment rates are relatively stable within each study, at least in more recent survey waves. However, as demonstrated in several of the articles in this issue, employment for any given respondent fluctuates, sometimes substantially, over time. These findings merely offer additional contextual information for interpreting the results of more rigorous analyses that consider individual respondents, children, or families as the unit of analysis.

Despite these limitations, we believe that the task of synthesizing trends across this group of panel studies is a useful endeavor. Many of our findings are consistent with results from experimental evaluations and leavers’ studies. The data in those studies suggest that on average, household income, earnings, and wages have improved among former and current welfare recipients, although such improvements appear to do little to lift families out of poverty, as most former welfare recipient families continue to experience economic hardship and to rely on other types of public benefits (e.g., Food Stamps, SSI).

Several hopeful signs emerged from this analysis. For example, we find some increases over time in survey respondents’ positive assessments of economic well-being, declines in coresidence with extended family (a positive trend if coresidence signals economic hardship, but a negative trend if coresidence indicates higher levels of social support), and increased participation in work support programs such as the EITC. Decreases in the use of charity/emergency assistance are somewhat unexpected, given incentives in PRWORA that encourage state cooperation with community and “faith-based” organizations in the delivery of welfare services—the so-called “charitable choice” provision (Cnaan & Boddie, 2002). Also, other research has documented at least modest growth in the use of emergency or charitable services, such as food pantry use, following the passage of PRWORA (Mosley & Tiehen, 2004; Tiehen, 2002). The fact that most studies in our analysis revealed declines in charity assistance could indicate declining need for such supplemental resources; however this finding could also indicate that families are having increasing trouble accessing these resources.

This analysis provides little evidence of broad changes in family formation and composition in the wake of welfare reform. Although increasing rates of marriage emerged in several of the studies, it is unclear whether these rising rates signify an emerging response to welfare reform. In addition, the overall rates of marriage remain low (around 20% or lower) as of the most recent survey waves. Nevertheless, with marriage promotion as a clear goal of welfare reform, this topic deserves more attention in future research.

In sum, many families affected by welfare reform remain dependent on public benefits, and either poor or near-poor, despite gains in some indicators of economic well-being. The remaining papers in this volume begin to address how parents and children are faring in other important domains.

In light of findings from previous welfare reform research, particularly the welfare leaver studies, our results suggest that low-income families continue to face economic hardship. The host of policy changes enacted in the late 1990s as well as a robust economy succeeded in increasing the labor force participation of many low-income women. However, few of these families achieved economic self sufficiency, and many continue to struggle to make ends meet. As such, increasing attention should be given to better understanding what type of strategies lead to higher wage rates for low-skilled mothers, including for example, job retention and advancement programs. In addition, these results suggest that families may benefit from expansions in work supports, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and child care assistance. Although benefits in these areas have increased since welfare reform, as state aid shrinks some supports may be less accessible. For example, 26 states have reduced the income eligibility for child care subsidies in recent years (Child Care Bureau, 2004).

Finally, we remind readers that aggregated data provide only a broad picture of how families are faring and we must be mindful that individual families experience variability in outcomes. While on average families appear to experience small gains over the course of each study, this likely masks considerable heterogeneity. Some families may be experiencing much more dire economic circumstances if, for example, they are unable to transition from welfare to work. A better understanding of which families are able to successfully transition from welfare into employment and which continue to struggle will provide a better indication of the types and ranges of services that may further support low-income families.

Acknowledgments

The studies included in this analysis were supported by grants from the Administration for Children and Families (90OJ202001; 90PA0005); Administration on Developmental Disabilities; the Annie E. Casey Foundation; the Boston Foundation; the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation; the Chicago Community Trust; the David and Lucile Packard Foundation; the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation; the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health; the Joyce Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; the Kronkosky Charitable Foundation; the Lloyd A. Fry Foundation; the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD P50 HD 38986; K01 HD41703-01; R01 HD39148; R01 HD36916; RO1 HD36093); the National Institute of Justice (2001-WT-BX-0002); the National Institute of Mental Health (R24-MH51363); the Office of the Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; the Office of the Vice-President for Research at the University of Michigan; the Polk Bros. Foundation; the Searle Fund for Policy Research; the Social Security Administration; the Substance Abuse Policy Research Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the U.S. Department of Education (R305T010869); the W.K. Kellogg Foundation; and the Woods Fund of Chicago. Data for the various studies were collected or provided by the Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago; Mathematica Policy Research; the Institute for Research on Poverty, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; the Institute for Survey and Policy Research at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; the Metro Chicago Information Center; the Research Triangle Institute; the Survey Research Center at University of Michigan; the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development; and the Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services.

Appendix A. Principal Study Investigators

WES

Sandra Danziger, Mary Corcoran, Sheldon Danziger, Kristin Seefeldt and Richard Tolman, University of Michigan and Ariel Kalil, University of Chicago.

IFS

Dan A. Lewis, Northwestern University; Paul Kleppner, Northern Illinois University; Stephanie Riger, University of Illinois at Chicago; James Lewis, Roosevelt University; and Robert Goerge, University of Chicago

MTAS

Mark Courtney, University of Chicago, and Irving Piliavin, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin-Madison

FF

Sara McLanahan and Christina Paxson, Princeton University and Irwin Garfinkel and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Columbia University, Co-Principal Investigators.

3-City

Andrew Cherlin, Johns Hopkins University; Ron Angel, University of Texas at Austin; Linda Burton, Duke University; P. Lindsay Chase-Lansdale, Northwestern University; Robert Moffitt, Johns Hopkins University; and William Julius Wilson, Harvard University.

Footnotes

See Appendix A for a list of investigators associated with each study.

The FF sample is nationally representative of births to unmarried women in mid- to large-size U.S. cities (i.e., those with populations of 200,000 or more).

Work triggers involve time limits on TANF receipt in the absence of employment or work activity, as defined by each state.

A third line of research involves econometric studies which capitalize on within-state changes to estimate the effects of particular aspects of welfare policy, such as family caps or time limits. Thus, this latter group of studies does not contribute to an understanding of the full effect of PRWORA (Blank, 2002).

The Illinois family cap policy was subsequently repealed in 2004.

Wisconsin’s waiver-based welfare demonstrations included Learnfare, Bridefare, and Work Not Welfare. Some of these demonstrations operated only in select counties or involved a small percentage of the total AFDC caseload (Corbett, 1995).

In contrast to TANF programs in many other states, there is no earnings disregard that would allow participants who work at low-wage jobs to still receive some cash assistance. exempt from the work requirement.

The five studies generated similar information on a wide range of outcomes and characteristics, but the precise measures used in each study may differ.

WES did not employ weights for non-response or attrition, although a previous analysis of WES data do not suggest that bias from attrition is a problem (Pape, 2004).

It is important to note that these trends in employment are derived from self-reported information, as opposed to Unemployment Insurance records. See Appendix B for detail on several of the measures presented in Tables 3 through 5.

For years in which a given study did not have a survey wave, the estimate represents the mid-point of the previous and subsequent year.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kristen Shook Slack, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Katherine Magnuson, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Lawrence Berger, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Joan Yoo, Columbia University.

Rebekah Levine Coley, Boston College.

Rachel Dunifon, Cornell University.

Amy Dworsky, Chapin Hall Center for Children, University of Chicago.

Ariel Kalil, University of Chicago.

Jean Knab, Princeton University.

Brenda J. Lohman, Iowa State University

Cynthia Osborne, University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Acs G, Loprest P, Roberts T. The final synthesis report of findings from ASPE’s leaver grants. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beverly SG. Measures of Material Hardship: Rationale and Recommendation. Journal of Poverty. 2001;5(1):23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Blank R. Evaluating Welfare Reform in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature. 2002;40(4):1105–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Brauner S, Loprest P. Where are they now? What states’ studies of people who left welfare tell us. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom D, Michalopoulos C. How welfare policies affect employment and income: A synthesis of research. NY, NY: Manpower Research Demonstration Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian M, Meyer D. Alternative Measures of Economic Success among TANF Participants: Avoiding Poverty, Hardship, and Dependence on Public Assistance. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2004;23(3):531–548. [Google Scholar]

- Center on Hunger and Poverty. Are States Improving the Lives of Poor Families? A Scale Measure of State Welfare Policies. Report. Medford, MA: Tufts University, Center on Hunger and Poverty; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Child Care Bureau. Trends in state eligbility. Washington, DC: Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Citro CF, Michael RT. Measuring Poverty: A New Approach. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cnaan R, Boddie S. Charitable choice and faith-based welfare: A call for social work. Social Work. 2002;47:224–235. doi: 10.1093/sw/47.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives. The Green Book: Background Data on Programs within the Jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett T. Welfare Reform in Wisconsin: The Rhetoric and the Reality. In: Norris DF, Thompson L, editors. The Politics of Welfare Reform. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Crouse G, Hauan S, Isaacs J, Swenson K, Trivits L. Indicators of Welfare Dependence. Annual Report to Congress, 2005. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Danziger SK, Corcoran M, Danziger S, Heflin C, Kalil A, Levine J, Rosen D, Seefeldt K, Siefert K, Tolman R. Barriers to the Employment of Welfare Recipients. In: Cherry R, Rodgers W, editors. Prosperity for All? The Economic Boom and African Americans. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2000. pp. 245–278. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Chase-Lansdale PL. For better and for worse: Welfare reform and the well-being of children and families, (pp.3–8) In: Duncan GJ, Chase-Lansdale PL, editors. For Better and For Worse: Welfare Reform and the Well-Being of Children and Families. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett B, Glied S. Does state AFDC generosity affect child SSI participation. Journal of Public Policy Analysis and Management. 2000;19:275–295. [Google Scholar]

- Grogger J, Karoly L. Welfare reform: Effects of a decade of change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton G, et al. National evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies: How effective are different welfare-to-work approaches? Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D, Shook K, Stevens A, Kleppner P, Lewis J, Riger S. Work, Welfare and Well-Being: An Independent Look at Welfare Reform in Illinois. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University, Institute for Policy Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Loprest P, Zedlewski S. The changing role of welfare in the lives of low-income families with children. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt R, Winder K. Does it pay to move from welfare to work? A comment on Danziger, Heflin, Corcoran, Oltmans, and Wang. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2005;24:399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley J, Tiehen L. The food safety net after welfare reform: Use of private and public food assistance in the Kansas City Metropolitan Area. Social Service Review. 2004;78(2):267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Pape A. How does attrition affect the Women’s Employment Study data? 2004. Unpublished manuscript available online at: http://www.fordschool.umich.edu/research/pdf/WES_Attrition-oct-edit.pdf.

- Piliavin I, Dworsky A, Courtney M. What Happens to Families under W-2 in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin? Report from Wave 2 of the Milwaukee TANF Applicant Study. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall Center for Children; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Public Law 104–193. (August 22, 1996). Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. 42 U.S.C. 1305.

- Rector R, Fagan PF. The continuing good news about welfare reform. The Heritage Foundation, Backgrounder, No. 1620. Washington, D.C.: Heritage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile Families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(4–5):303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles P. Drawing the Line: Alternative Poverty Measures and their Implications for Public Policy. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt K, Anderson N. Inside Michigan Work First Programs. 2000. Michigan Program on Poverty and Social Welfare Policy Report Available online at: http://www.fordschool.umich.edu/research/poverty/pdf/insidemich_prtc.pdf.

- Seefeldt K, Pavettti L, Maguire K, Kirby G. Income support and social services for low-income people in Michigan. 1998. Urban Institute Publication available online at: http://www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=308028.

- Schmidt L. Effects of welfare reform on the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. Ann Arbor, MI: National Poverty Center Poverty Brief #4; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L, Sevak P. AFDC, SSI, and welfare reform aggressiveness: Caseload reductions versus caseload shifting. Journal of Human Resources. 2004;39:3–812. [Google Scholar]

- Tiehen L. Use of food pantries by households with children rose during the late 1990s. Food Review. 2002 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Poverty and Health Statistics Branch/HHES Division. Washington, D.C.: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]