Key Points

Spontaneous regression of B-cell tumors in Eμ-myc mice.

Regression depends on DNAM-1, natural killer cells, and T cells.

Abstract

Mechanisms of spontaneous tumor regression have been difficult to characterize in a systematic manner due to their rare occurrence and the lack of model systems. Here, we provide evidence that early-stage B cells in Eμ-myc mice are tumorigenic and sharply regress in the periphery between 41 and 65 days of age. Regression depended on CD4+, CD8+, NK1.1+ cells and the activation of the DNA damage response, which has been shown to provide an early barrier against cancer. The DNA damage response can induce ligands that enhance immune recognition. Blockade of DNAM-1, a receptor for one such ligand, impaired tumor regression. Hence, Eμ-myc mice provide a model to study spontaneous regression and possible mechanisms of immune evasion or suppression by cancer cells.

Introduction

Myc expression is deregulated in around 70% of all human malignancies.1 Eμ-myc mice overexpress murine c-myc under the control of immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer region (Eμ), analogous to human Burkitt lymphoma.2 Previous studies of Eμ-myc mice demonstrated proliferating immature B cells appearing in the periphery after birth, followed by their disappearance after around 6 weeks of age and the appearance of B-cell lymphomas in 50% of mice by 15 to 20 weeks of age.3-5 The mechanisms leading to the disappearance of early proliferating B cells are poorly understood.

Oncogenic stress created by sustained MYC expression induces DNA damage in both preneoplastic and tumors cells of Eμ-myc transgenic mice through a variety of mechanisms.6-9 DNA damage and the ensuing DNA damage response has been proposed to represent an anticancer barrier in early tumorigenesis.10-12 We and others have shown that the DNA damage response alerts the innate immune system by inducing the expression of ligands for the activating immune receptors DNAM-1 and NKG2D.13,14 These receptors mediate recognition of normal self-molecules that are upregulated by tumors and “stressed” cells.15 Recent studies suggest that DNAM-1 and NKG2D contribute to immune surveillance of tumors.16 NKG2D-deficient Eμ-myc mice show an accelerated development of B-cell lymphomas, suggesting that NKG2D mediates natural killer (NK) or T-cell–dependent recognition and lysis of B-cell lymphomas.17 Furthermore, Eμ-myc mice that lacked the gene encoding Rag1 showed an accelerated development of B-cell lymphomas, consistent with the possibility that T cells participate in immune surveillance of B-cell lymphomas in Eμ-myc mice.18

DNAM-1 is an adhesion molecule that is constitutively expressed by most immune cells.16 The expression of DNAM-1 ligands, which include CD112 and CD155, is often upregulated in tumor cells and can induce NK and CD8+ T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion in vitro.19 DNAM-1–deficient mice have impaired rejection of some tumor cells and develop more tumors in response to chemical carcinogens.20

Here, we show that DNA damage response–induced expression of the DNAM-1 ligand CD155 in tumor cells leads to spontaneous rejection of tumor cells from the blood of young Eμ-myc mice. Antibody-blocking studies demonstrated a critical role for NK1.1+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells in tumor regression from blood, spleen, and lymph nodes. Our results show that the DNA damage response–initiated anticancer barrier in early tumorigenesis depends on DNAM-1 ligand upregulation and the ensuing immune response. Hence, Eμ-myc mice are a suitable novel model to study spontaneous rejection of tumor cells, which so far has been difficult to characterize in a systematic manner due to its rare occurrence.

Methods

Mice and cells

Mice were housed and bred in pathogen-free conditions in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 041/08) guidelines at the National University of Singapore, in accordance with the National Advisory Committee for Laboratory Animal Research Guidelines (Guidelines on the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes). BC2 cells were a generous gift of Dr L.M. Corcoran (WEHI, Australia).21 Eμ-M1 cells were derived from a late-stage Eμ-myc mouse as described previously.21 BC2 or Eμ-M1 cells were pretreated with 7.7 mM caffeine or phosphate-buffered saline for 1 hour, followed by treatment of cells with 10 μM Ara-C or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) for 16 hours (all reagents were obtained from Sigma, Singapore).

Flow cytometry and cytology

Blood was collected by facial bleeding and red blood cells were removed by red blood cell lysis or Ficoll gradient centrifugation. Fc receptors on blood cells were blocked by preincubating cells with CD16/CD32-specific antibodies for 10 min (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Tumor cells were stained with combinations of B220-PerCP and immunoglobulin M (IgM) Ag-presenting cell or IgM-fluorescein isothiocyanate–specific antibodies (eBioscience). Cells were stained for CD155 (Hyclone, Thermo, Singapore), CD112 (clone W-16 or 6A6006; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; or clone 502-57; Hycult Biotech, Uden, The Netherlands), major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I (H-2Kb or H-2Kd), MHC class II, CD40, CD62L, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1; eBioscience), pan-RAE-1, DNAM-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and Ag-presenting cell–coupled-rat IgG-specific antibodies (eBioscience, USA). Staining of cells was analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and FlowJo. 8.8.7 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Tumor load was calculated as follows: ∑ (% IgM−B220low) × % B220+ + (IgM+B220low) × % B220+. For cell-cycle analysis, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and blood was analyzed 18 hours later. BrdU incorporation and annexin V+ staining were assessed by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Pharmingen, Singapore). For ex vivo annexin V staining, tumor cells were cultured in RPMI (Invitrogen, Singapore) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Thermo, Singapore), 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 µM asparagine, 2 mM glutamine (Sigma), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) for 30 minutes to remove adherent cells. Nonadherent cells were removed to a fresh flask and cultured at 37°C for 5 hours before annexin V staining. In some cases, peripheral blood smears were stained with Giemsa and examined under light microscopy for the presence of blastic and abnormal lymphoid cells by an independent oncologist (W.J.C.) and pathologist (S.B.N.).

Concentration of tumor cells in the blood was calculated by multiplying the lymphocyte count determined using a Scil Vet abc animal blood cell counter (Horiba, Selangor, Malaysia) by the percentage of B220low cells in a forward light scatter/side light scatter gate corresponding to lymphocytes as determined by flow cytometry.

Western blotting

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from purified B220+ cells (>95% purity, mouse B-cell enrichment kit, Stemcell Technology, Singapore), electrophoresed in 8%, 12%, or 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels, and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies specific for phospho–H2AX-Ser139 (H2AX-P-Ser139), phospho–ATM-Ser1981 (ATM-P-Ser1981), ATM, phospho–CHK1-Ser345 (Chk1-P-Ser345), CHK1, phospho–p53-Ser15 (p53-P-Ser15), p53, p21CIP, phospho–CDK2-Thr160 (CDK2-P-Thr160), CDK2, pRB, phospho–Rb-Ser608 (Rb-P-Ser608), CYCLIN A, CYCLIN D1, PUMA, c-MYC (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Sigma), and horseradish peroxidase–coupled second-stage reagents were used to develop the blots (Thermo, Singapore). Blots were exposed on x-ray film (Fuji, Singapore).

Adoptive transfers

severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) common γ chain−/− mice were divided into groups of 5 and injected intravenously with 5 × 106 B220low or B220+ cells from pre- or postregression Eμ-myc mice or BC2 cells as positive controls. Splenocytes were purified using an EasySep B Cell Enrichment Kit (B220+; Stemcell Technology) followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting of B220low cells. Injected mice were bled at days 5, 12, 19, and 77 posttransfer for flow cytometric analysis of tumor load.

In vivo blocking studies

Between 32 and 36 days of age, Eμ-myc mice were separated into groups with similar tumor loads. Mice received 500 μg anti-NK1.1 (PK136; ATCC, Manassas, VA) twice, 7 days apart, or 100 μg anti-DNAM-1 (10E5; Dr V. Kuchroo, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) twice, 7 days apart, or 500 μg anti-CD4 (GK1.5; a kind gift of Dr J. Wong, NUS, Singapore) and 250 μg anti-CD8 (Clone #2.43, ATCC) twice a week, 4 days apart, or equivalent amounts of isotype control antibodies injected intraperitoneally.

In vivo KU55933 treatment

At 37 days of age, Eμ-myc mice were separated into groups with similar tumor loads. Mice received 5 mg/kg intraperitoneal KU55933 or vehicle control (10% DMSO/cyclodextrin/phosphate-buffered saline). Mice were given KU55933 at 37, 39, 47, 49, and 54 days of age. Blood tumor load was measured at 37, 44, and 58 days of age. In addition, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg BrdU at 57 days of age for cell-cycle analysis and blood was analyzed 18 hours later for BrdU incorporation.

PCR

Total RNA of early and late IgM−B220low and IgM+B220low tumor cells of Eμ-myc mice was isolated using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Singapore). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays were performed using an ABI GeneAmp system 2700 (ABI, Singapore). Two micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed with random hexamers using a M-MLV reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Singapore). Each amplification mixture (50 μL) contained 25 ng reverse-transcribed RNA, 0.5 μM forward primer, 0.5 μM reverse primer, and 10 μL Phusion HF buffer (Thermo), 200 μM of each 2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphate, and 0.02 U/μL Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo). PCR thermocycling parameters were 98°C for 45 seconds and 30 cycles of 98°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 15 seconds. The following forward primers were used: MKV.B1 5′-GATGTTTTGATGACCCAAACT-3′; MKV.B2 5′-GATATTGTGATGACGCAGGCT-3′; MKV.B3 5′-GATATTGTGATAACCCAG-3′; MKV.B4 5′-GACATTGTGCTGACCCAATCT-3′; MKV.B5 5′-GACATTGTGATGACCCAGTCT-3′; MKV.B6 5′-GATATTGTGC TAACTCAGTCT-3′; MKV.B7 5′-GATATCCAGATGACACAGACT-3′; MKV.B8 5′-GACATCCAGCTGACTCAGTCT-3′; MKV.B9 5′-CAAATTGTTCTCACCCAGTCT-3′; MKV.B10 5′-GACATTCTGATGACCCAGTCT-3′. The reverse primer was MKC.F 5′-GGATACAGTTGGTGCAGCATC-3′.

Statistical analyses

Mean percent tumor load between groups was compared using 2-tailed unpaired t tests (Prism, 5.0c, GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Survival was represented by Kaplan-Meier curves and statistical analysis of survival was performed with the log-rank Mantel-Cox test. P < .05 denotes significance.

Results

Spontaneous regression of B220low cells in the periphery of Eμ-myc mice

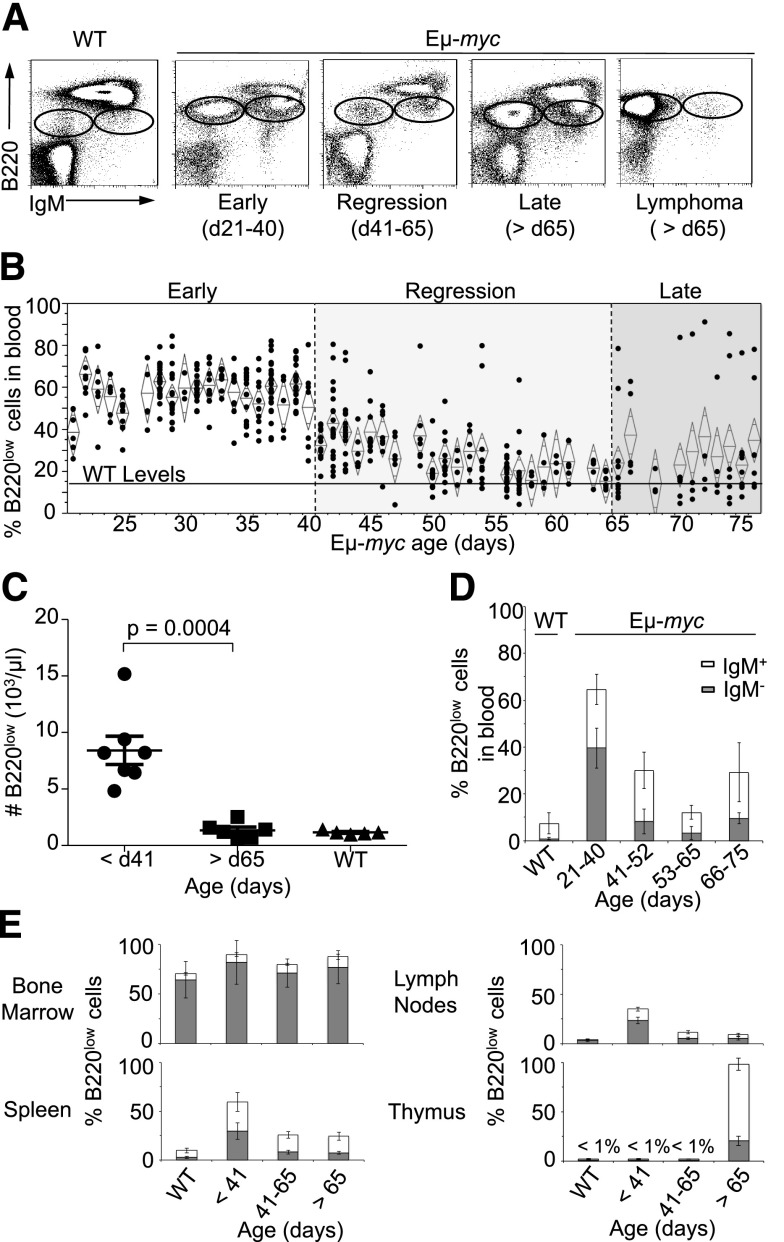

As previously reported, a large number of IgM−B220low and IgM+B220low cells22 (subsequently referred to as B220low cells) were present in the blood of Eμ-myc mice as early as 21 days of age.3-5 Surprisingly, we observed a sharp decrease in the percentage of B220low cells in the blood of Eμ-myc mice between 41 and 65 days of age with levels of B220low cells becoming indistinguishable from that of control mice by 57 days of age (Figure 1A-C). Eµ-myc mice before 41 days of age had approximately 8 times more B220low cells than mice after 65 days of age (Figure 1C). The loss of B220low cells was due to the disappearance of IgM−B220low cells (black bars) early during regression and IgM+B220low cells between 53 and 65 days of age (Figure 1D). In Eμ-myc mice older than 65 days, high percentages of B220low cells reappeared in some of the mice, suggesting sporadic recurrence of cancer (Figure 1B). Tumors appearing after 65 days of age fell into 2 categories: those that were IgM−B220low (80%) and those that were IgM+B220low (20%) (supplemental Figure 1). For comparison, at early or late time points, blood samples from nontransgenic C57BL/6 mice contained low percentages of B220low cells (Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Spontaneous regression of B220low cells in the blood of Eμ-myc mice. (A) Blood tumor load was assessed by flow cytometry. Dot plots are representative of blood stained for B220 and IgM expression. Oval gates identify B220low populations in Eμ-myc mice. (B) Longitudinal analysis of tumor load in peripheral blood of Eμ-myc or WT mice. Each point (·) represents percentage of B220low cells in the blood of individual Eμ-myc mice. Mice were sacrificed after developing signs of disease. Diamond represents mean tumor load per time point and 95% confidence limit. Mean percentage of B220low cells in the blood of WT mice is represented by a black line. (C) Number of B220low cells in the peripheral blood of Eμ-myc or WT mice. Concentration of tumor cell in the blood was calculated by multiplying the number of blood lymphocytes determined by an animal blood counter and percentage of B220low blood cells assessed by flow cytometry. Data represent mean tumor load per time point and 95% confidence limit. (D) Percentage ± standard deviation (SD) of B220low cell subtypes in the blood of Eμ-myc mice (n = 10 per time-point) and WT mice (n = 5) at indicated age: IgM− (gray bars), IgM+ (white bars). (E) Longitudinal analysis of the B220low cells in spleen, thymus, bone marrow, and lymph node of Eμ-myc mice. Mean percentage ±SD of IgM−B220low (gray bars) and IgM+B220low (white bars) cells in the indicated organs of Eμ-myc mice (n = 10 per time point) and WT mice (n = 5) before 41 days of age (early), between 41 and 65 days of age (regression), and post–65 days of age (late) is shown. d, day.

A possible explanation for the loss of B220low cells from the blood at 41 to 65 days of age reflected altered trafficking of leukemic cells into other sites or organs. However, this is unlikely because we did not observe increased numbers of tumor cells in other organs (Figure 1E and supplemental Figure 3). Instead, we observed decreased numbers of B220low cells in the spleen and lymph nodes at 41 to 65 days of age, which we designated the regression phase (Figure 1E). The percentage of precursor B220low cells in the bone marrow was comparable to the percentage in nontransgenic mice and was roughly constant at all stages of disease (Figure 1E). Only at the very late-stage of disease (>120 days of age) did we observe tumor-cell invasion of the thymus (Figure 1E), consistent with observable thymic lymphoma (data not shown).

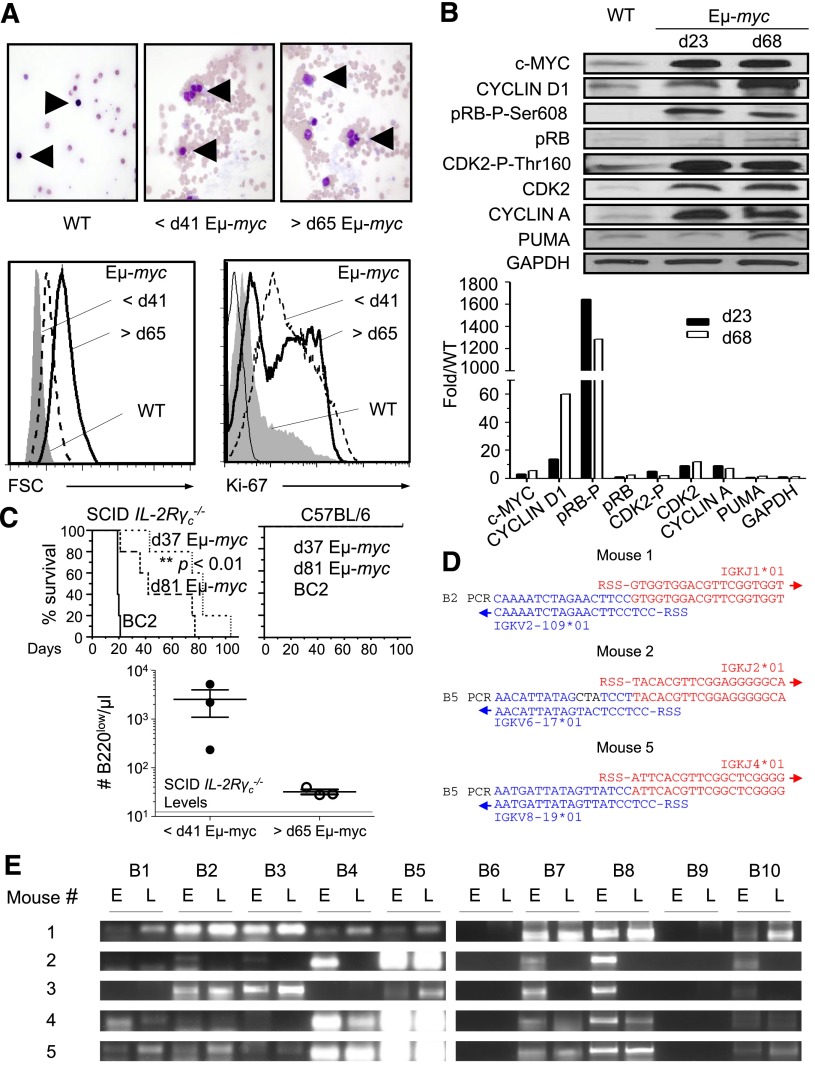

B220low cells appearing before spontaneous regression are malignant

Single-blind histopathological analysis and forward light scatter analysis of purified pre- and postregression B220low cells revealed high numbers of cytologically malignant lymphoid cells with enlarged and irregular nuclei, similar to leukemic cells observed in the peripheral blood of human B-cell lymphoma in the leukemic phase, indicating that these cells are proliferating and morphologically malignant (Figure 2A). Furthermore, pre- and postregression B220low cells expressed the tumor marker KI-67 (Figure 2A). As expected for tumor cells, proteins important for S phase entry, such as CYCLIN D1, CYCLIN A, phosphorylated pRB, and CDK2, were upregulated in B220low cells of Eμ-myc mice when compared with wild-type (WT) cells. We did not observe a significant difference in the expression levels of S phase–associated proteins in pre- and postregression B220low cells with the exception of CYCLIN D1, which was higher in postregression B220low cells (Figure 2B). Interestingly, CYCLIN D1 was shown to collaborate in lymphomagenesis of c-myc–overexpressing B cells and is located in the vicinity of a break point in the chromosomal translocation t(I1:14) found in some human B-cell lymphomas.23,24 A hallmark of tumor cells is their ability to give rise to tumors when transferred into a recipient subject. Transfer of 5 × 106 B220low or B220+ cells derived from Eμ-myc mice before 41 days of age or after 65 days of age into SCID IL-2Rγc−/− mice resulted in the presence of B220low cells in the blood and terminal disease in both cases, though it was delayed upon transfer of preregression compared with postregression B220low cells (Figure 2C). Tumorigenesis is a multistep process, and it is plausible that tumor cells appearing after 65 days of age are derived from preregression tumor cells that have acquired additional mutations resulting in a more malignant phenotype.25 PCR amplification experiments revealed similar immunoglobulin κ light chain gene-rearrangement patterns and (where tested) identical Vκ -Jκ junctional sequences in pre- and postregression tumors of Eμ-myc mice, providing strong support for the conclusion that preregression tumors are clonal precursors of tumor cells appearing after 65 days of age in Eμ-myc mice (Figure 2D-E).26

Figure 2.

Early B220low cells are clonal precursors of postregression tumor cells. (A) Smear preparation of blood of pre- and postregression Eμ-myc mice. Giemsa-stained blood smears from WT revealed lymphocytes with small nuclei (upper left) while those from Eμ-myc mice at <41 days of age (upper middle) and >65 days of age (upper right) showed atypical lymphoid cells with enlarged and irregular nuclei. Arrows indicate lymphoid cells. Giemsa-stained blood smears were analyzed by light microscopy at original magnification ×600. B220low cells of WT (filled gray), preregression Eμ-myc mice (dashed line), or postregression Eμ-myc mice (black line) were assessed for size by forward light scatter (lower left panel) and for intracellular KI-67 expression (lower right) by flow cytometry. (B) Expression levels of cell-cycle–related proteins in splenic B220+ cells of Eμ-myc mice at 23 and 68 ± 2 days of age and B220+ cells of WT mice at 23 days of age. Quantification of bands is shown in lower panel. Expression levels were normalized to WT levels. Shown is 1 of 3 representative experiments. (C) Splenic B220low cells isolated from Eμ-myc mice at 37 and 81 ± 2 days of age were analyzed for malignant transformation by transfer of 5 × 106 B220+ cells into SCID IL-2Rγc−/− mice. BC2 cells, a cell line derived from Eμ-myc mice, were transferred as a positive control. Kaplan-Meier survival curve of SCID IL-2Rγc−/− (left panel) or WT mice (right panel) after transfer of B220+ cells (top panel). In a separate experiment, 5 × 106 splenic B220+ cells of individual Eμ-myc mice before 41 and after 65 days of age were transferred into different SCID IL-2Rγc−/− mice. The number of B220low cells in the blood of SCID IL-2Rγc−/− mice 77 days after transfer was determined as outlined in Figure 1C. Mean number of B220low cells in the blood of SCID IL-2Rγc−/− mice is represented by a black line (bottom). (D) V-J junction sequences of the immunoglobulin κ light chain of pre- and postregression tumors. Complimentary DNA samples of preregression and postregression Eμ-myc mice (n = 5) were amplified by PCR using primers hybridizing to related sets of V regions of the κ light-chain genes in combination with a primer specific for the constant region (see “Methods” and supplemental Figure 4). Identical V-J junction sequences of pre- and postregression tumors of 3 out of 5 mice are shown. No successful V-J recombinations were found in the remaining 2 mice. Successful V-J junctions were compared with germline sequence of C57BL/6 mice using IMGT/V-QUEST (http://www.imgt.org). Blue letters show the V region, red letters indicate the J region, and black letters show mutations. (E) Complimentary DNA of blood tumor cells of pre- and postregression Eμ-myc mice was amplified using primers specific for different variable regions of the κ light chain and a common primer specific for the constant region of the light chain according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Progen Biotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). d, day; E, tumors before 41 days of age; FSC, forward light scatter; L, tumors after 65 days of age; RSS, recombination signal sequences.

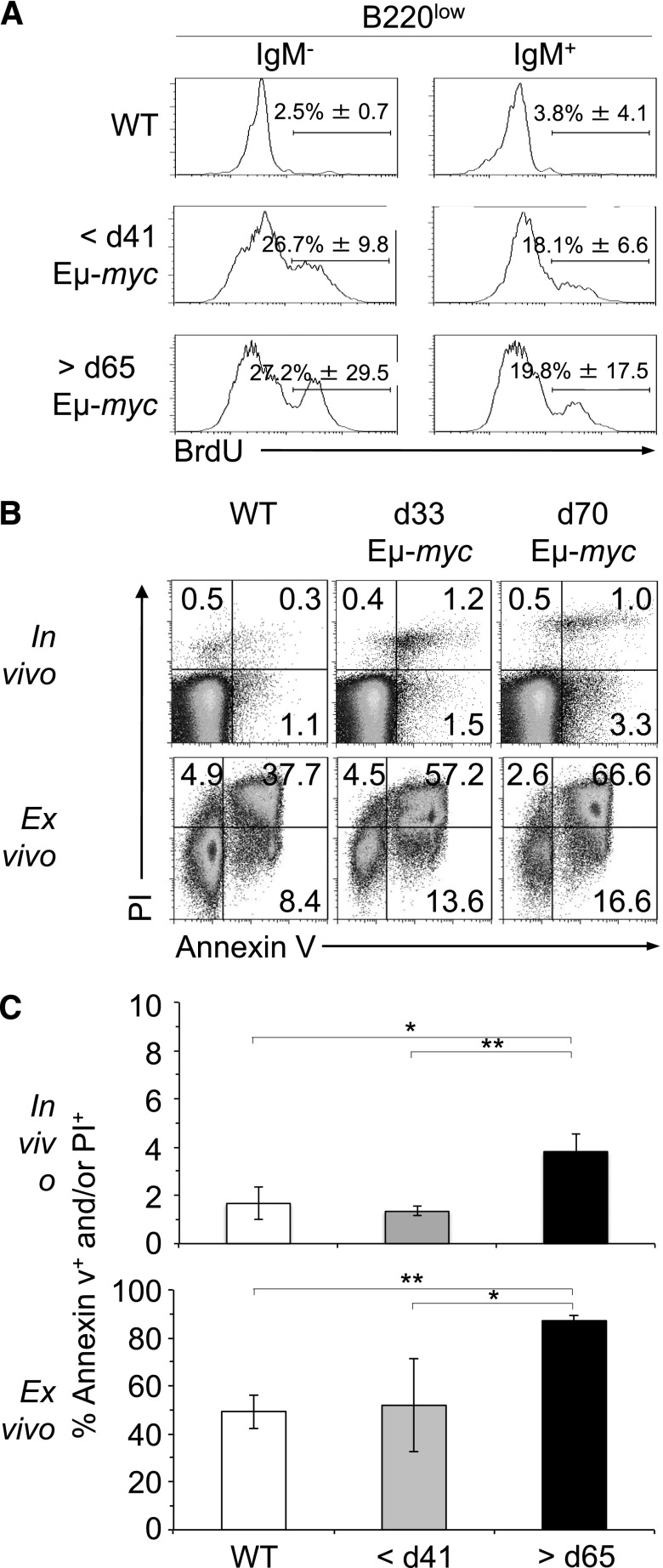

B220low cells appearing after spontaneous regression show higher rate of apoptosis

To address potential explanations for the disappearance of tumor cells during the regression stage, we compared the proliferative and cell death/apoptosis status of pre- and postregression tumor cells. Analysis of BrdU incorporation and DNA content revealed that pre- and postregression B220low cells of Eμ-myc mice incorporated significantly more BrdU than B220low cells in the blood of WT mice (Figure 3A), suggestive of their transformed status. In preregression Eμ-myc mice, B220low cells incorporated similar levels of BrdU than B220low cells appearing after regression (Figure 3A), although BrdU incorporation in postregression tumor cells was more variable, likely due to the stochastic nature of tumor progression following regression (Figure 1B). BrdU incorporation of preregression B220low cells, overexpression of cell-cycle proteins, splenomegaly, and the tumorigenic potential of these cells after transfer (Figure 2 and data not shown) are consistent with the conclusion that preregression B220low cells in Eμ-myc mice are malignant.

Figure 3.

Regression is not caused by changes in the rate of proliferation of tumor cells. (A) B220low cells of Eμ-myc and WT mice were stained for IgM and examined for BrdU incorporation and DNA content by flow cytometry. Eμ-myc mice at 33 and 70 ± 2 days of age and WT mice were injected intraperitoneally with 2 mg BrdU, and B220low blood cells were analyzed for IgM expression and BrdU incorporation 18 hours later. Numbers in quadrants indicate mean percentage of BrdU+ cells ±SD in each. Dot plots are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B-C) Detection of apoptotic cells by PI and annexin V staining of B220low cells from blood of WT mice at 33 days of age and Eμ-myc mice at 33 and 70 ± 2 days of age (>5 n each; upper panels). B220low cells of WT and Eμ-myc mice were also cultured for 5 hours before staining with PI and annexin V (>5 n each; lower panels). PI- and/or annexin V–positive cells were considered apoptotic. P values are indicated as HP < .05 and HHP < .01. d, day.

To compare the rates of apoptosis, we analyzed preregression, postregression, and WT B220low cells for annexin V expression and propidium iodide (PI) uptake. The percentage of apoptotic cells (annexin V+ and/or PI+) was increased in postregression Eμ-myc mice when tested in vivo and after 5 hours ex vitro culture (Figure 3A-C). These data support the conclusion that tumor cells appearing after 65 days of age were more prone to apoptosis, possibly due to increased levels of p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) in comparison with preregression tumor cells (Figure 2B). In summary, our analysis revealed that changes in cell intrinsic apoptosis pathways may contribute to regression.

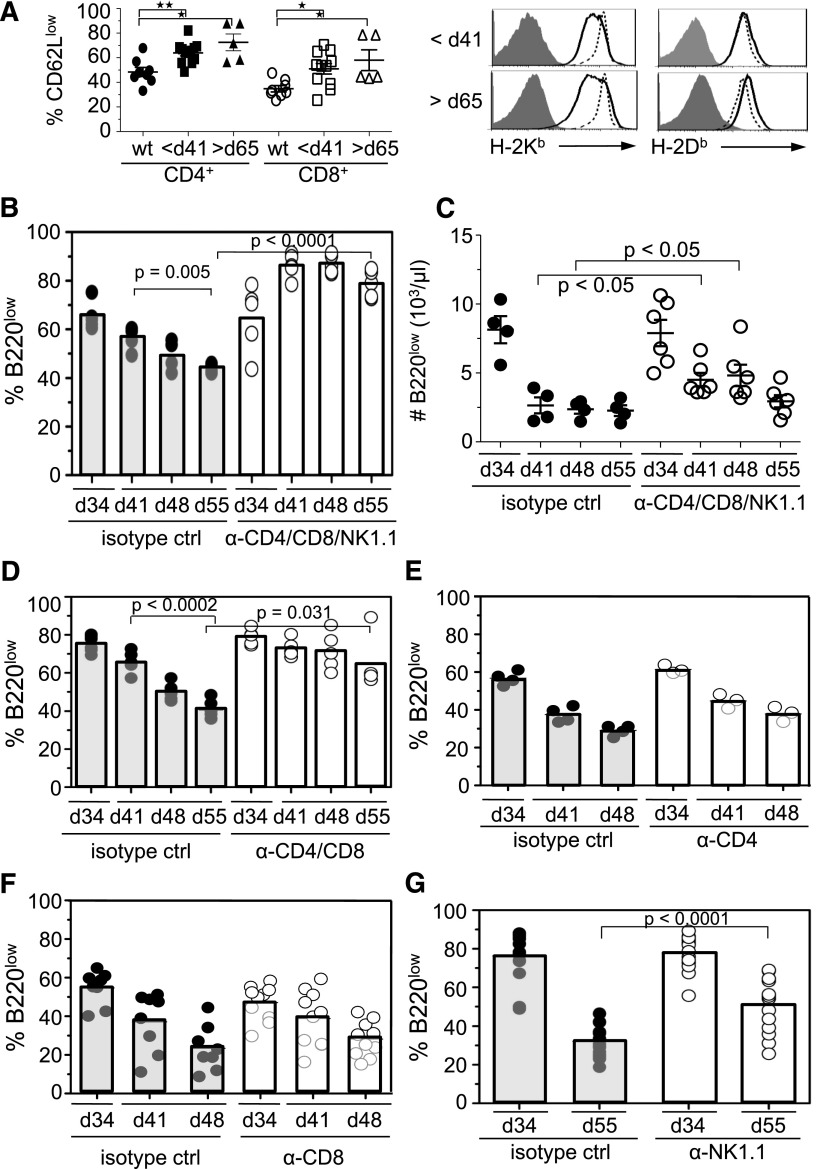

Spontaneous regression of B220low cells in periphery depends on T and NK cells

Apoptosis can also be triggered in cells via extrinsic pathways. The immune system is thought to play an important role in the suppression of tumors.27 In this context, it was striking that whereas pre- and postregression B220low cells resulted in lethal disease after transfer to SCID IL-2Rγc−/− mice, the same cells transferred to WT mice failed to develop tumors (Figure 2C). These data implicated the immune system in preventing tumor formation. Two findings were of interest in this regard. First, there were more CD62Llow cells, a phenotype indicative of T-cell activation, among blood CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in Eμ-myc mice than in WT mice (Figure 4A). Second, tumor cells in Eμ-myc mice older than 24 days exhibited decreased cell-surface display of MHC class I H-2Kb molecules, raising the possibility that “missing-self” recognition of tumor cells by NK cells may contribute to the disappearance of tumor cells (Figure 4A and supplemental Figure 4).28

Figure 4.

T and NK cells mediate regression of tumor cells in blood. (A) Percentage of CD62LlowCD3+CD4+, CD62LlowCD3+CD8+ T cells and MHC class I (H-2Kb and H-2Db) levels on B220low cells in the blood of preregression and postregression Eμ-myc mice and WT mice at <41 days of age (bold lines). Staining of MHC class I expression was compared with WT B220low cells (dashed line) or isotype controls (filled histogram). P values are indicated as HP < .009 and HHP = .001. (B-G) To determine effector mechanisms of tumor regression in vivo, Eμ-myc mice at 34 ± 2 days of age were treated with (B,C) anti-CD4 (500 μg/mouse), anti-CD8 (250 μg/mouse), and anti-NK1.1 (500 μg/mouse) antibodies. In some experiments mice were treated with anti-CD4 and CD8 antibodies (D), anti-CD4 (E), anti-CD8 (F), or anti-NK1.1 (G). Tumor load in the blood was determined by flow cytometry at 34 days of age (preregression) and during regression at 41 (B-F), 48 (B-F), and 55 days of age (B,C,D,G). Because T-cell depletion influences the percentage of tumor load in the blood, tumor load at 41 days of age was compared with the tumor load at 48 and 55 days of age. (C) The number of B220low cells in blood was determined as outlined in Figure 1C. Graphs represent the combined data from 2 independent experiments. ctrl, control; d, day.

To address if immune cell subsets mediate the decrease of tumor cells in the blood of Eμ-myc mice, we depleted NK and/or T cells at 34 days of age, just prior to the time when regression typically occurred. Simultaneous depletion of NK1.1+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells prevented tumor regression, assessed as the percentage of B220low cells in the blood over the next 21 days (Figure 4B). To compensate for the increase in the blood tumor percentage due to the depletion of NK and T cell, we compared the tumor load in NK- and T-cell–depleted Eμ-myc mice and measured total number of tumor cells in the blood (Figure 4C). These data suggested that immune cells, as opposed to cell-intrinsic mechanisms, are required for the tumor-cell loss during regression (Figure 4B-C). Simultaneous depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Figure 4D), but not separate depletions of CD4+ or CD8+ cells (Figure 4E-F), still significantly impaired the loss of tumor cells from the blood. Depletion of NK1.1+ cells by themselves also inhibited tumor regression (Figure 4G).

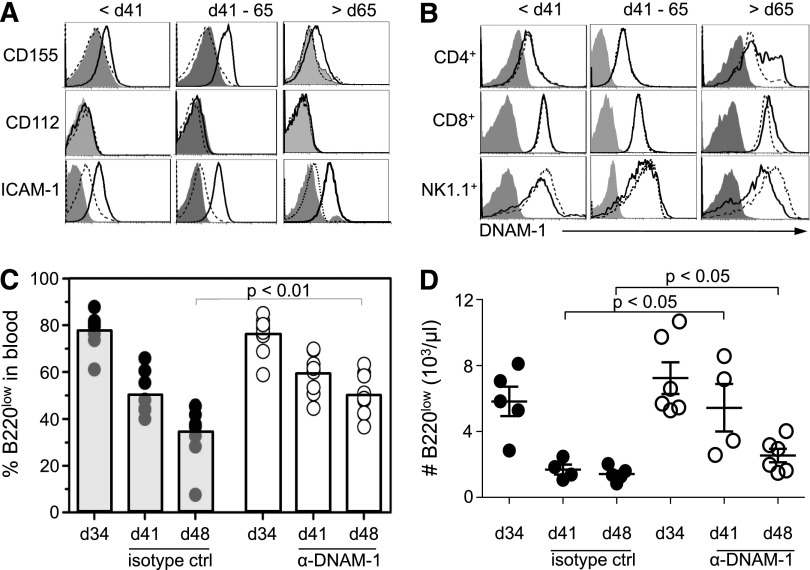

Spontaneous regression of B220low cells in periphery depends on DNAM-1

Ligands for the activating immune receptors NKG2D (RAE1, MULT1, H60), DNAM-1 (CD112 and CD155), and LFA-1 (ICAM-1), which associates with DNAM-1,29 can enhance the susceptibility of tumor cells to NK- and T-cell–mediated lysis.16 Expression of CD155 and ICAM-1 was increased on tumor cells before regression and further upregulated on tumor cells during regression when compared with B220high cells or IgM−B220low bone marrow cells from WT mice consistent with a possible role of CD155 in regression (Figure 5A, supplemental Figure 5, and data not shown). CD155 expression decreased on tumor cells appearing after regression to levels found on preregression tumor cells, possibly due to immune recognition and elimination of tumor cells expressing higher levels of CD155. Consistent with a role for CD155 in regression, the percentage of DNAM-1+CD4+ T cells increased in postregression Eμ-myc mice (Figure 5B). In contrast to DNAM-1 ligands, the RAE1 and MULT1 ligands for NKG2D, which have been implicated in immunosurveillance in Eμ-myc mice,17 were not detected on tumor cells before 65 days of age (data not shown).17 These data are consistent with evidence that NKG2D ligands are only expressed from 9 weeks of age onwards,9,17 and suggest that spontaneous regression in Eμ-myc mice does not depend on NKG2D-mediated recognition. Together, these data suggest possible roles for DNAM-1 ligands in regression and do not support a role for NKG2D ligands.

Figure 5.

DNAM-1 partially mediates regression of tumor cells in blood. (A) DNAM-1 ligands and ICAM-1 levels on B220low cells in the blood of preregression, regression, and postregression Eμ-myc mice (bold lines) were compared with WT B220high cells (dashed line) or isotype control stainings (filled histogram). (B) Analysis of DNAM-1 levels on CD4+CD3+, CD8+CD3+ T cells and NK1.1+CD3− NK cells from blood of preregression, regression, and postregression Eμ-myc mice (bold lines). Staining was compared with WT NK cells or T cells (dashed line) or isotype controls (filled histogram). (C-D) To determine effector mechanisms of tumor regression in vivo, Eμ-myc mice at 34 days of age were treated with anti–DNAM-1 antibody (100 μg/mouse). Tumor load (C) and B220low cell number (D) in the blood was determined by flow cytometry at 34, 41, and 48 days of age. The number of B220low cells in blood (D) was determined as outlined in Figure 1C. Graphs represent the combined data from 2 independent experiments. ctrl, control; d, day.

To investigate a role for DNAM-1 in tumor regression, DNAM-1 was blocked with antibodies prior to the onset of regression in Eμ-myc mice starting at 34 days of age. DNAM-1 blockade in Eμ-myc mice inhibited tumor-cell loss compared with treatment with an isotype control antibody (Figure 5C-D). Thus, our data suggest that regression of B220low tumor cells in the blood of Eμ-myc mice depends at least in part on DNAM-1–mediated immunosurveillance.

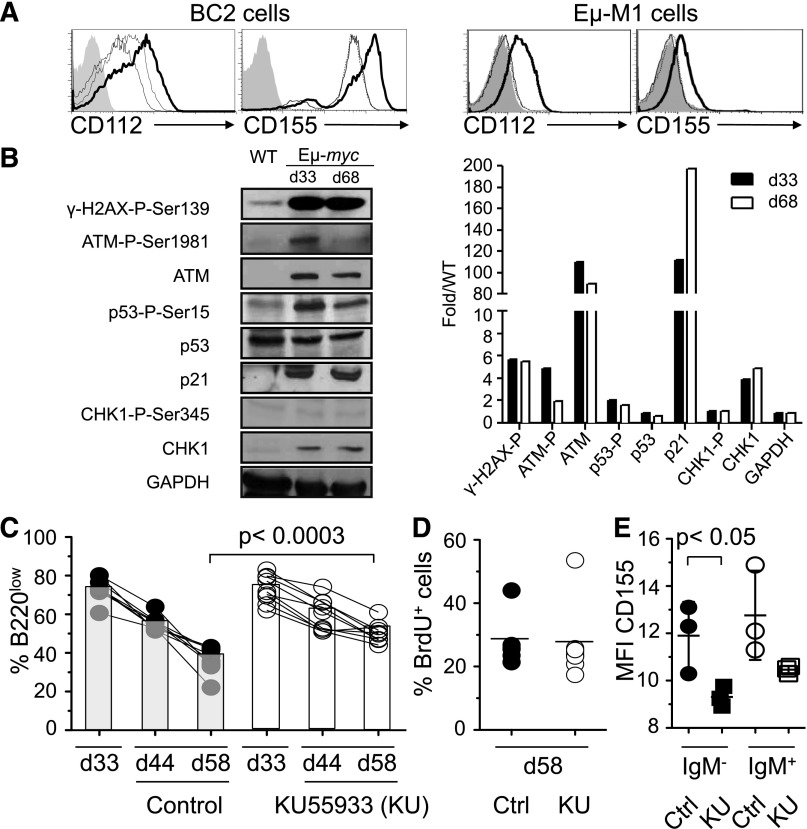

Spontaneous regression of B220low cells in periphery depends on ATM

In light of evidence that DNAM-1 ligands are induced by an active DNA damage response, we investigated the status of proteins that mediate the DNA damage response (Figure 6A and Soriani et al14). These included ATM (ataxia telangiectasia, mutated) and ATR (ATM and RAD3 related),30 which initiate the DNA damage response and activate downstream substrates CHK2 and CHK1, respectively. These signal transducers phosphorylate effector proteins such as p53, E2F1, and CDC25 family members, which inhibit cell-cycle progression and induce DNA repair systems. If the DNA damage is too extensive, then the p53 family members trigger apoptosis or senescence. Western blot analysis showed elevated ATM-P-Ser1981, p53-P-Ser15, γ-H2AX-P-Ser139, and p21Cip1 expression in pre- and postregression B220low tumor cells, demonstrating that the ATM-initiated DNA damage response was activated in tumor cells prior to regression (Figure 6B). To establish a role for the DNA damage response in the regression of tumor cells, Eμ-myc mice were treated with the ATM inhibitor KU55933 intraperitoneally starting at 37 days of age (Figure 6C). KU55933-treated mice demonstrated a significantly increased tumor load in the blood at 44 and 58 days of age when compared with vehicle-treated Eμ-myc mice (Figure 6C). The increased tumor load was not due to abrogation of the DNA damage response-dependent cell-cycle arrest, because we did not observe increased BrdU incorporation in tumor cells of KU55933-treated mice at 58 days of age (Figure 6D). The extent of BrdU incorporation at 58 days of age in control-treated mice (Figure 6D) was similar to that in preregression tumor cells (Figure 3A), consistent with the conclusion that regression is not caused by a decrease in the proliferation rate. Furthermore, administration of KU55933 at 28 days of age had no effect on the tumor load in the blood, suggesting that the tumor load was not controlled by ATM-mediated cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis prior to regression (data not shown). Notably, the expression of CD155 was reduced on IgM−B220low cells 30 hours after the first administration of KU55933 at 37 days of age, consistent with the idea the ATM-dependent regression partially depends on CD155 (Figure 6E). Taken together, our data suggest that an ATM-dependent DNA damage and immune response contribute to the regression of B220low tumor cells in the blood of Eμ-myc mice.

Figure 6.

Regression of B220low tumor cells in blood depends on the DNA damage response. (A) BC2 or Eμ-M1, cell lines derived from Eμ-myc mice, were treated with DMSO (fine line) or 10 μM Ara-C (bold line), a DNA-damaging agent, for 16 hours and stained for CD112 and CD155 expression. Some cells were pretreated with the 7.7 mM of the ATM/ATR inhibiting drug caffeine for 1 hour before treatment with Ara-C (dashed line) or DMSO (dotted line) for 16 hours. Filled histogram represents Ara-C–treated cells stained with isotype control. (B) Immunoblot analysis of purified B220low cells (>98% purity) from Eμ-myc mice at 33 and 68 ± 2 days of age or WT mice probed with antibodies for indicated DNA damage response markers. Levels were quantitated and normalized to WT levels (right panel). Shown is 1 out of 3 representative experiments. (C-E) Eμ-myc mice were injected intraperitoneally with 5 mg/kg KU55933 (n = 9) or vehicle (n = 8) at 37, 39, 47, 49, and 54 days of age. Percentage of B220low cells in the blood of an individual Eμ-myc mouse was determined at 33, 44, and 58 days of age by flow cytometry (C). KU55933-treated (open circles) or vehicle-treated (filled circles) mice also received 1 mg BrdU at 57 days of age. B220low tumor cells were stained for incorporation of BrdU and the percentage of BrdU+ B220low tumor cells was determined by flow cytometry at 58 days of age (D). Thirty hours after first injection of KU55933 (squares) or vehicle (circles), B220low cells were stained for CD155 and IgM expression. Mean fluorescence intensity of CD155 expression on IgM−B220low (filled symbols) and IgM+B220low (open symbols) cells is depicted (E). Statistical significance is indicated. Ctrl, control; d, day; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

Oncogenic stress created by sustained MYC expression was shown to induce DNA damage in tumors cells of Eμ-myc transgenic mice through DNA double-strand breaks and increased reactive oxygen species.6-8 Previous studies suggested that loss of “preneoplastic” cells may be partially due to DNA damage response–induced cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis.31,32 Here, we show that Eμ-myc mice undergo spontaneous tumor regression in the blood between 41 and 65 days of age. Remarkably, regression was consistent between large numbers of mice, suggesting a synchronized mechanism of control. Although intrinsic tumor-suppressor mechanisms, in particular apoptosis, are likely to play a role in the control of lymphomagenesis, spontaneous regression was severely impaired in NK- and T-cell–depleted Eμ-myc mice suggesting that regression is mainly mediated by extrinsic pathways. In agreement with this observation, recent studies showed that survival of RAG1-deficient Eμ-myc mice was reduced when compared with RAG1-sufficient mice.18 However, the same author later showed that Tcrα−/− and Tcrδ−/−-deficient Eμ-myc mice showed no significant impact on lymphomagenesis in Eμ-myc mice.33 A possible explanation for the discrepancy with our data is that Tcrα+ and Tcrδ+ are required for immunosurveillance in Eμ-myc mice.

Blocking of DNAM-1 reduced regression of tumor cells in the blood, demonstrating a role for DNAM-1 in the recognition and elimination of DNAM-1 ligand–expressing B220low tumor cells. DNAM-1 is constitutively expressed on immune cells including Th1 CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells.34,35 DNAM-1 is physically and functionally associated with LFA-1, whose ligand, ICAM-1, was upregulated on B220low tumor cells and may therefore contribute to tumor-cell recognition in Eμ-myc mice.36 Activation of DNAM-1 on NK and CD8+ T cells stimulates cytotoxicity and interferon-γ expression, which promotes Th1 differentiation of CD4+ T cells and cell-cycle arrest of some cells.37-40 A role for interferon-γ in regression of tumor cells in Eμ-myc mice was suggested by the increased percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of DNAM-1 postregression. CD4+ T cells were previously found to work in concert with NK cells in tumor clearance.41 Several studies have also reported that antigen-specific CD4+ T cells can acquire cytotoxic properties.42,43 Moreover, CD4+ T cells have been shown to contribute to the sustained tumor regression upon MYC inactivation.44 However, expression levels of MYC and one of its target genes, CYCLIN D1, was similar or even increased in tumor cells after 65 days of age, suggesting that tumor regression at 41 to 65 days of age was not caused by MYC inactivation.45

Previous studies suggested that NKG2D ligands were upregulated on tumor cells at late-stage (from 9 weeks onwards).9,17 Confirming these earlier studies, we failed to observe NKG2D ligand expression on tumors at early time points (between 3 and 9 weeks; data not shown). Our data therefore suggest that the upregulation of ligands for DNAM-1 on tumor cells prior to regression is critical for the spontaneous regression of tumor cells, although NKG2D-mediated recognition of tumor cells appears to play a role in immune surveillance of tumors because NKG2D deficiency was shown to accelerate the progression of Eμ-myc–induced lymphomas.17 The role of DNAM-1 in immune surveillance after regression has not been investigated in the current study, but it is likely that DNAM-1 contributes to tumor recognition after 65 days of age. Interestingly, DNAM-1 expression is often lost on immune cells in Eμ-myc mice that develop large lymphomas (data not shown). Exposure of human NK cells to DNAM-1 ligand–expressing tumor cells has been reported to attenuate DNAM-1 expression on the tumor-associated lymphocytes, allowing the tumor cells to escape immune surveillance.46 Depleting NK and T cells or blocking of DNAM-1 during the regression phase did not affect the survival of the Eμ-myc, suggesting that the antitumor response after the regression phase might be able to control the lymphomagenesis in Eμ-myc mice (data not shown).

These data support the possibility that loss of DNAM-1 expression may play a part in allowing tumor cells to escape immune surveillance. In accordance, C57BL/6 mice developed tumors after administration of tumor cells derived from large late-stage lymphomas whereas tumors derived from late-stage mice with low tumor burden were rejected, suggesting that tumors at the late-stage of disease become gradually less immunogenic (data not shown and Kelly et al47).

The fact that regression was delayed until 41 to 65 days of age despite an early activation of the DNA damage response in tumor cells indicates that DNA damage may need to attain a certain threshold to exert its immunity-inducing effects. Alternatively, inhibitory mechanisms may set a threshold for immune activation, which is eventually overcome between 41 and 65 days of age. Consistent with this possibility, we found that expression of H-2Kb, which binds to inhibitory receptors on NK cells, was downregulated before regression. Finally, it is possible that regression may require a more mature immune system to initiate an antitumor immune response.

In summary, we describe here a novel mechanistic pathway that can be used to study spontaneous regression of B-cell lymphomas in the established Eμ-myc mouse model. In humans, spontaneous regression is a rare phenomenon.48,49 Spontaneous regression of tumors most frequently occurs in melanoma, hypernephroma, and neuroblastoma.50 Non-Hodgkin lymphomas and Burkitt lymphoma have also been reported to undergo spontaneous regression.50,51 The mechanisms underlying spontaneous regression are poorly understood and have been suggested to include infections, increased immune responses, differentiation, and apoptosis.51 Lymphocyte infiltration and T-cell expansion have been observed in a number of cases of spontaneous tumor regression, providing circumstantial evidence for a role of immune cells in tumor regression.52 Furthermore, immune suppression by clinical intervention in patients is associated with a heightened risk of developing certain types of malignancy in particular lymphomas.52 To our knowledge, this study provides the first in vivo evidence that tumor regression is mediated by T cells and NK cells. Regression by these immune cells required the activation of the DNA damage response and the activating immune receptor DNAM-1. Our findings are supported by previous data showing that DNAM-1 is important for immunosurveillance of primary spontaneous tumors but also appears to contribute to tumorigenesis, perhaps by applying more selection pressure.20,53 The reactivation of the immune response leading to spontaneous regression may provide a promising novel approach to treat cancer.54 Treatments targeting DNAM-1 ligands on tumors in conjunction with other strategies for interfering with the immune system may provide therapeutic efficacy during late-stage cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr V. Kuchroo (Harvard Medical School, Boston, US) for the kind gift of 10E5 hybridoma.

This work was supported by grants from the Biomedical Research Council (07/1/21/19/513), the National Research Foundation (HUJ-CREATE - Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Inflammation), the National Medical Research Council (NMRC/1158/2008), SIgN (07-007 from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore), and the US National Institutes of Health (D.H.R.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.J.L, T.L.F.M., P.M.F., and H.C.W performed all the experiments except the ATM inhibition and the T-cell and NK double- and triple-depletion experiments (T.L.F.M.), the CD112 and CD155 expression on cell lines (K.N.), the histology of tumors (P.C.M.L and N.S.B), and the light-chain PCRs (S.G.). C.J.L., P.M.F., R.D.H., and S.G. participated in study design and data analysis. C.J.L., R.D.H., and S.G. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephan Gasser, Immunology Programme, Department of Microbiology, National University of Singapore, 117456, Singapore; e-mail: micsg@nus.edu.sg.

References

- 1.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams JM, Gerondakis S, Webb E, et al. Cellular myc oncogene is altered by chromosome translocation to an immunoglobulin locus in murine plasmacytomas and is rearranged similarly in human Burkitt lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80(7):1982–1986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.7.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langdon WY, Harris AW, Cory S, et al. The c-myc oncogene perturbs B lymphocyte development in E-mu-myc transgenic mice. Cell. 1986;47(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidman CL, Denial TM, Marshall JD, et al. Multiple mechanisms of tumorigenesis in E mu-myc transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 1993;53(7):1665–1669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris AW, Pinkert CA, Crawford M, et al. The E mu-myc transgenic mouse. A model for high-incidence spontaneous lymphoma and leukemia of early B cells. J Exp Med. 1988;167(2):353–371. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pusapati RV, Rounbehler RJ, Hong S, et al. ATM promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenesis in response to Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(5):1446–1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507367103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray S, Atkuri KR, Deb-Basu D, et al. MYC can induce DNA breaks in vivo and in vitro independent of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2006;66(13):6598–6605. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vafa O, Wade M, Kern S, et al. c-Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene-induced genetic instability. Mol Cell. 2002;9(5):1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unni AM, Bondar T, Medzhitov R. Intrinsic sensor of oncogenic transformation induces a signal for innate immunosurveillance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(5):1686–1691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701675105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartek J, Bartkova J, Lukas J. DNA damage signalling guards against activated oncogenes and tumour progression. Oncogene. 2007;26(56):7773–7779. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartkova J, Horejsí Z, Koed K, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434(7035):864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou LV, Karakaidos P, et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434(7035):907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, et al. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. 2005;436(7054):1186–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature03884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soriani A, Zingoni A, Cerboni C, et al. ATM-ATR-dependent up-regulation of DNAM-1 and NKG2D ligands on multiple myeloma cells by therapeutic agents results in enhanced NK-cell susceptibility and is associated with a senescent phenotype. Blood. 2009;113(15):3503–3511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raulet DH, Guerra N. Oncogenic stress sensed by the immune system: role of natural killer cell receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(8):568–580. doi: 10.1038/nri2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerra N, Tan YX, Joncker NT, et al. NKG2D-deficient mice are defective in tumor surveillance in models of spontaneous malignancy. Immunity. 2008;28(4):571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nepal RM, Zaheen A, Basit W, et al. AID and RAG1 do not contribute to lymphomagenesis in Emu c-myc transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2008;27(34):4752–4756. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bottino C, Castriconi R, Pende D, et al. Identification of PVR (CD155) and Nectin-2 (CD112) as cell surface ligands for the human DNAM-1 (CD226) activating molecule. J Exp Med. 2003;198(4):557–567. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iguchi-Manaka A, Kai H, Yamashita Y, et al. Accelerated tumor growth in mice deficient in DNAM-1 receptor. J Exp Med. 2008;205(13):2959–2964. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corcoran LM, Tawfilis S, Barlow LJ. Generation of B lymphoma cell lines from knockout mice by transformation in vivo with an Emu-myc transgene. J Immunol Methods. 1999;228(1-2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yukawa K, Kikutani H, Inomoto T, et al. Strain dependency of B and T lymphoma development in immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer (E mu)-myc transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1989;170(3):711–726. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovec H, Grzeschiczek A, Kowalski MB, et al. Cyclin D1/bcl-1 cooperates with myc genes in the generation of B-cell lymphoma in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1994;13(15):3487–3495. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodrug SE, Warner BJ, Bath ML, et al. Cyclin D1 transgene impedes lymphocyte maturation and collaborates in lymphomagenesis with the myc gene. EMBO J. 1994;13(9):2124–2130. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma A, Fisher P, Dildrop R, et al. Surface IgM mediated regulation of RAG gene expression in E mu-N-myc B cell lines. EMBO J. 1992;11(7):2727–2734. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ljunggren HG, Kärre K. In search of the ‘missing self’: MHC molecules and NK cell recognition. Immunol Today. 1990;11(7):237–244. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shibuya K, Lanier LL, Phillips JH, et al. Physical and functional association of LFA-1 with DNAM-1 adhesion molecule. Immunity. 1999;11(5):615–623. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gasser S, Raulet D. The DNA damage response, immunity and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16(5):344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, et al. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature. 2011;478(7370):515–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reimann M, Loddenkemper C, Rudolph C, et al. The Myc-evoked DNA damage response accounts for treatment resistance in primary lymphomas in vivo. Blood. 2007;110(8):2996–3004. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nepal RM, Tong L, Kolaj B, et al. Msh2-dependent DNA repair mitigates a unique susceptibility of B cell progenitors to c-Myc-induced lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(44):18698–18703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905965106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dardalhon V, Schubart AS, Reddy J, et al. CD226 is specifically expressed on the surface of Th1 cells and regulates their expansion and effector functions. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1558–1565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bottino C, Castriconi R, Moretta L, et al. Cellular ligands of activating NK receptors. Trends Immunol. 2005;26(4):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibuya A, Campbell D, Hannum C, et al. DNAM-1, a novel adhesion molecule involved in the cytolytic function of T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4(6):573–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)70060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryceson YT, March ME, Ljunggren H, et al. Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood. 2006;107(1):159–166. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shibuya K, Shirakawa J, Kameyama T, et al. CD226 (DNAM-1) is involved in lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 costimulatory signal for naive T cell differentiation and proliferation. J Exp Med. 2003;198(12):1829–1839. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seder RA, Gazzinelli R, Sher A, et al. Interleukin 12 acts directly on CD4+ T cells to enhance priming for interferon gamma production and diminishes interleukin 4 inhibition of such priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(21):10188–10192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wall L, Burke F, Barton C, et al. IFN-gamma induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells in vivo and in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(7):2487–2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez-Diez A, Joncker NT, Choi K, et al. CD4 cells can be more efficient at tumor rejection than CD8 cells. Blood. 2007;109(12):5346–5354. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quezada SA, Simpson TR, Peggs KS, et al. Tumor-reactive CD4(+) T cells develop cytotoxic activity and eradicate large established melanoma after transfer into lymphopenic hosts. J Exp Med. 2010;207(3):637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie Y, Akpinarli A, Maris C, et al. Naive tumor-specific CD4(+) T cells differentiated in vivo eradicate established melanoma. J Exp Med. 2010;207(3):651–667. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rakhra K, Bachireddy P, Zabuawala T, et al. CD4(+) T cells contribute to the remodeling of the microenvironment required for sustained tumor regression upon oncogene inactivation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adhikary S, Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(8):635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlsten M, Norell H, Bryceson YT, et al. Primary human tumor cells expressing CD155 impair tumor targeting by down-regulating DNAM-1 on NK cells. J Immunol. 2009;183(8):4921–4930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelly PN, Dakic A, Adams JM, et al. Tumor growth need not be driven by rare cancer stem cells. Science. 2007;317(5836):337. doi: 10.1126/science.1142596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang E, Selleri S, Sabatino M, et al. Spontaneous and treatment-induced cancer rejection in humans. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8(3):337–349. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burnet FM. The concept of immunological surveillance. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1970;13:1–27. doi: 10.1159/000386035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drobyski WR, Qazi R. Spontaneous regression in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: clinical and pathogenetic considerations. Am J Hematol. 1989;31(2):138–141. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830310215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papac RJ. Spontaneous regression of cancer: possible mechanisms. In Vivo. 1998;12(6):571–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1137–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilfillan S, Chan CJ, Cella M, et al. DNAM-1 promotes activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes by nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells and tumors. J Exp Med. 2008;205(13):2965–2973. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sengupta N, MacFie TS, MacDonald TT, et al. Cancer immunoediting and “spontaneous” tumor regression. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]