Abstract

Recent reports of localized larval recruitment in predominately small-range fishes are countered by studies that show high genetic connectivity across large oceanic distances. This discrepancy may result from the different timescales over which genetic and demographic processes operate or rather may indicate regular long-distance dispersal in some species. Here, we contribute an analysis of mtDNA cytochrome b diversity in the widely distributed Brown Surgeonfish (Acanthurus nigrofuscus; N = 560), which revealed significant genetic structure only at the extremes of the range (ΦCT = 0.452; P < .001). Collections from Hawaii to the Eastern Indian Ocean comprise one large, undifferentiated population. This pattern of limited genetic subdivision across reefs of the central Indo-Pacific has been observed in a number of large-range reef fishes. Conversely, small-range fishes are often deeply structured over the same area. These findings demonstrate population connectivity differences among species at biogeographic and evolutionary timescales, which likely translates into differences in dispersal ability at ecological and demographic timescales. While interspecific differences in population connectivity complicate the design of management strategies, the integration of multiscale connectivity patterns into marine resource planning will help ensure long-term ecosystem stability by preserving functionally diverse communities.

1. Introduction

The recent dramatic decline of marine ecosystems [1–3] has led to an increased interest in the use of spatially explicit management strategies, such as no-take marine reserves, to promote ecosystem stability [4–9]. Yet designing marine reserves that can support a community’s ability to absorb and recover from recurrent ecosystem disturbances requires an understanding of the scale and magnitude of population connectivity for a wide range of species and environments [9–13]. While there have been a number of recent, remarkable insights into larval dispersal distances for some taxonomic groups (e.g., Damselfishes [13, 14]), the lack of data for the majority of species continues to limit the integration of dispersal dynamics into reserve planning and design.

Most near-shore marine species exhibit an early pelagic larval phase (reviewed in [15, 16]) and larval duration has been repeatedly explored as a surrogate for species dispersal ability [17–20]. However, a comprehensive review found average pelagic larval duration (PLD) to be a poor predictor of genetic structure, and by extension dispersal ability, with previously reported correlations driven by species lacking a pelagic larval phase [21]. While a correlation between dispersal ability and general reproductive strategy may hold (i.e., brooders versus nonbrooders; reviewed in [22, 23]), there appears to be little evidence of a consistent relationship between species PLD and patterns of population connectivity [21, 24].

Recent reports emphasizing the influence of species ecology on dispersal and connectivity [25–30] may offer some insight into the discrepancy between PLD and other estimates of dispersal. For example, ecological specialists appear to be less dispersive and less successful colonizers than generalists [31]. With respect to direct larval exchange, pronounced interspecific differences in larval swimming ability and larval response to environmental signals have been identified [22, 32, 33], and inclusion of larval behavior in dispersal models can dramatically change predicted levels of local retention and larval dispersal distances [34]. The difficulty in tracking minute larvae has, however, restricted direct evaluation of dispersal distances to a small number of studies.

Whether employing induced otolith tags or multi locus parentage assignment, direct larval tracking has consistently revealed unexpectedly high levels of local larval retention [13, 14, 35–38]. In turn, this has led to the proposal that larval retention near natal sources may be a common phenomenon of reef fishes [14, 39] and of marine species in general [35]. The long-held perception that marine populations are broadly open [40–43] has now shifted towards an emphasis on the retention of larvae near source populations (reviewed in [44]), with a resulting change in recommendations for resource management [23, 37]. Yet with the exception of the Vagabond Butterflyfish (Chaetodon vagabundus), direct tests of larval dispersal have only been applied to fishes with small geographic ranges (<6,000 km median longitudinal range) that are restricted to either the tropical West Pacific [13, 14, 36, 37], Caribbean [35], or Mediterranean [39]. Conversely, the majority of Indo-Pacific reef fishes have longitudinal ranges exceeding 10,000 km [20], indicating that the conclusion of high larval retention may not apply to all reef species.

Dispersal ability is thought to play an important role in establishing and maintaining large geographic ranges (see [20, 45–48], but see [49, 50]). There is conflicting evidence, however, whether species’ current distributions can be used to inform spatially explicit resource planning. A comparison of dispersal distances calculated from genetic isolation-by-distance (IBD) slopes for a taxonomically diverse group of reef species [51] found no relationship between dispersal ability and species geographic range size [50]. Though, because IBD analyses assume equilibrium between migration and genetic drift (i.e., equilibrium between forces adding and culling genetic diversity), IBD-based estimates of dispersal distances have been shown to differ from known values by more than 300% [52]. Biogeographic support for a positive relationship between range size and dispersal ability can be found in the least dispersive reef species; those lacking a pelagic larval phase often have smaller geographic ranges than similar species with pelagic larval dispersal [53, 54]. Likewise, genetic assessments of Hawaiian reef fishes have consistently found endemic fishes to be genetically subdivided across the 2,600 km archipelago, while more broadly distributed species reveal a lack of barriers to gene flow over the same region (see [55–58], but see [59]).

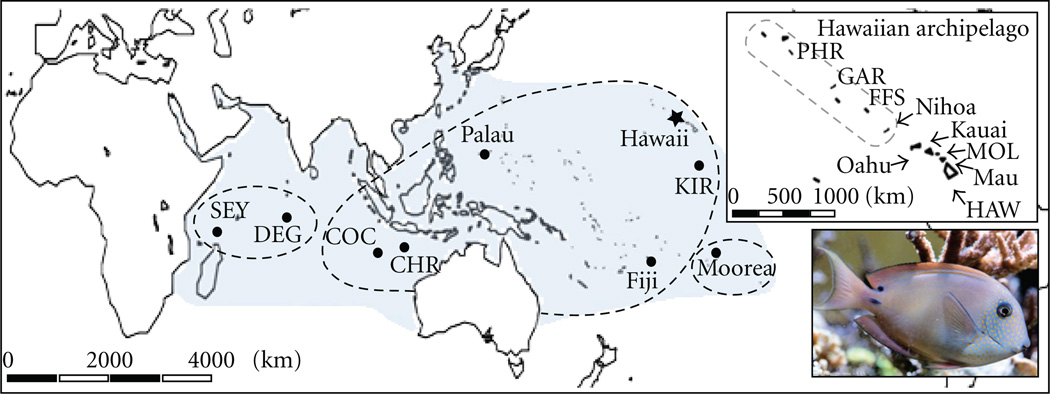

To further investigate the relationship between species range size and patterns of population connectivity, we assessed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) diversity in the Brown Surgeonfish (Acanthurus nigrofuscus) across a range that stretches from the east coast of Africa to Hawaii and Pitcairn Island in the Central Pacific [60, Figure 1]. The Brown Surgeonfish is a “generalist” herbivore that occurs in a variety of habitats from lagoons to forereefs, with feeding behavior that varies between seasons and locations [60–62]. The geographic distribution of the Brown Surgeonfish is similar to many Indo-Pacific species, covering a longitudinal distance of more than 21,000 km and straddling the well described biogeographic barrier centered on the Indo-Malay Archipelago, the Indo-Pacific Barrier (IPB [63]). A previous assessment of Brown Surgeonfish population genetic structure within Hawaii indicated extensive gene flow throughout the 2,600 km archipelago (ΦST =−0.006, P = .752 [64]), a pattern consistent with expectations of large-scale population connectivity in widely distributed species. In addition, we contrast phylogeographic patterns (i.e., geographic distribution of genetic diversity) from the Brown Surgeonfish and other broadly distributed fishes to those from co-occurring small range species to offer some insight into how recent findings of high larval retention can be applied to marine communities and to the development of ecosystem-based management strategies.

Figure 1.

Location of Brown Surgeonfish (Acanthurus nigrofuscus) collection sites. Collections in Hawaii were made in June/July 2005–06, and elsewhere from September 2006 to June 2009. Inset details collections within the Hawaiian Archipelago, with the boundary of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument indicated by the dashed circle. Site abbreviations are as follows: SEY, Seychelles; DEG, Diego Garcia; COC, Cocos Islands; CHR, Christmas Island; KIR, Kiritimati; PHR, Pearl and Hermes Reef; GAR, Gardner Pinnacles; FFS, French Frigate Shoals; MOL, Molokai; HAW, Hawaii Island. Dashed borders on the main map indicate site groupings as determined in Samova. Photo credit: http://www.aquaportail.com/.

Similar phylogeographic comparisons have provided valuable insights into species’ life history [65, 66], ecology [67–69], and population history (see [24, 59, 65], reviewed in [70]). However, reliance on mtDNA markers presents some challenges. Of particular concern are the strikingly different temporal and spatial scales that genetic and demographic processes operate [71, 72]. Because most population genetic approaches integrate historical and contemporary processes, strong historical signals (e.g., colonization events) can obscure more recent patterns of gene flow [73, 74]. Additionally, demographic independence of populations can occur even when migration is high enough to inhibit genetic differentiation—meaning that a lack of genetic differentiation can not be taken as proof of frequent larval exchange [74, 75]. Therefore, rather than directly assessing ongoing larval exchange, we use findings from the Brown Surgeonfish to set up a qualitative assessment of the relationship between reef fish biogeography (range size) and population connectivity. While the increasing use of genomic molecular analyses continues to improve the resolution of fine-scale connectivity patterns (reviewed in [76]), we confine our comparison to mtDNA markers because their relative abundance offers opportunities for comparisons not yet possible with other markers.

2. Materials and Methods

Tissue collections from Hawaii (N = 281 [64]) were supplemented with range-wide sampling (N = 279; Figure 1). The combined 560 Brown Surgeonfish were collected from 17 Indo-Pacific locations with polespears while snorkeling or with SCUBA. DNA was extracted using a standard salting out protocol [77], and a 694 bp section of mtDNA cytochrome b was amplified using the heavy strand primer (5’-GTGACTTGAAAAACCACCGTTG-3’) from [78] and light strand primer (5’-ACAGTGCTAATGAGGCTAGTGC-3’) modified from [79]. PCR and sequencing protocols are described in [58]. In brief, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification mixes consisted of 3.0 mM MgCl2, 0.26 µM of each primer, 50 nM dNTPs, 1.0 units Taq DNA polymerase and 2.0 µL of 10x PCR buffer (Bioline USA Inc., Taunton, Mass) in 20 µL total volume. PCR thermal cycling consisted of an initial denaturing step at 94° C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94, 55, and 72°C for 30 s each, with a final extension of 72°C for 10 min. Sequencing reactions with fluorescently labeled dideoxy terminators were analyzed on an ABI 3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif) in the EPSCoR genetic analysis facility at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. Only rare and questionable haplotypes were sequenced in both directions. Newly derived unique haplotypes have been deposited in Gen Bank (accession numbers HQ157717–157797). Resulting sequences were aligned in Mafft 6.62 [80].

Haplotype (h) and nucleotide (π) diversities for each collection site were calculated in Arlequin 3.11 [81] which implements diversity index algorithms described in [82]. Differences in diversity values were assessed with a one-sided T-test. A statistical parsimony network of haplotypes was constructed using TCS 1.2.1 [83].

Population structure was assessed with a spatial analysis of molecular variance (Samova 1.0 see [84]). Samova removes bias in population designation by implementing a simulated annealing procedure within the analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) framework (Arlequin 3.11) to identify maximally differentiated groupings without a priori assumptions of group identity. To ensure validity of the maximally differentiated groupings, the simulated annealing process was repeated 100 times from a different initial partition of samples into K groups. The configuration with the largest, statistically significant estimate of among group differentiations (Φct) is retained as the best sample grouping. Samova was run with values of K = 2 to 10 to identify the most likely number of populations. Because Samova cannot be run for K = 1, a separate AMOVA analysis was conducted with all collections combined into a single group. Deviations from random expectations were tested with 20,000 permutations. Patterns of pairwise genetic differentiation among individual sampling sites (Φst) were estimated in Arlequin with the mutational model of Tamura and Nei [85], which was identified as the best fit to the data by the Akaike information criterion (AIC) as employed in Modeltest [86, 87]. We also calculated standardized estimates of allele frequency differences, Dest (equation 13 see [88]).

A Mantel test with 10,000 simulations was used to test for an isolation-by-distance (IBD) signature (a positive correlation between geographic and genetic distance measures [89, 90]). To provide insight into how the spatial scale of gene flow may differ across potentially interconnected islands and across large stretches of open ocean, IBD tests were conducted separately on the full data set and within Samova-defined populations.

We tested for a signature of population expansion with Fu’s Fs [91] and by comparing observed and expected pairwise mismatch distributions [92] in Arlequin with 90,000 simulated samples. Fu [91] noted that Fs is particularly sensitive to deviations from a constant population size, with population expansion resulting in a significant, negative Fs. If there was evidence of population expansion, we estimated ancestral and contemporary female effective population sizes (Nef) from the equation: θ = Nef2 μt, with μ being the estimated annual fragment mutation rate and t is the estimated generation time. Estimates of pre- and post expansion θ were derived from the sudden expansion model of the mismatch distributions. Population ages in years were estimated from the population age parameter (τ), with τ = 2 μT, where T is the time since the most recent bottleneck. We provisionally applied a generation time of 5 years for the Brown Surgeonfish [92] and a within lineage, annual-per-site mutation rate of 1.55 × 10−8 per year [93].

3. Results

Cytochrome b sequencing revealed 110 closely related haplotypes (h = 0.65–0.91; π = 0.0017–0.0045 Table 1). Haplotype diversity in Hawaii (h = 0.65–0.87) is similar to other peripheral collections (Seychelles and Moorea, h = 0.72–0.78) but is significantly lower than central Indo-Pacific collections (Diego Garcia to Kiritimati, h = 0.85–0.89; one way T-test, P < .001).

Table 1.

Brown Surgeonfish collection sites with sample size, haplotype diversity (h), and nucleotide diversity (π) per sample and for the overall data set (Total), with standard deviations in parentheses.

| Location | N | h | π |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearl and Hermes Reef | 20 | 0.87 (0.06) | 0.0045 (0.0027) |

| Gardner Pinnacles | 25 | 0.72 (0.08) | 0.0021 (0.0014) |

| French Frigate Shoals | 33 | 0.72 (0.08) | 0.0021 (0.0013) |

| Nihoa | 40 | 0.73 (0.06) | 0.0026 (0.0016) |

| Kauai | 26 | 0.81 (0.06) | 0.0023 (0.0015) |

| Oahu | 39 | 0.70 (0.07) | 0.0019 (0.0013) |

| Molokai | 29 | 0.71 (0.08) | 0.0024 (0.0016) |

| Maui | 36 | 0.77 (0.06) | 0.0030 (0.0018) |

| Hawaii Island | 33 | 0.65 (0.09) | 0.0022 (0.0015) |

| Kiritimati | 35 | 0.89 (0.04) | 0.0032 (0.0020) |

| Fiji | 30 | 0.91 (0.03) | 0.0031 (0.0020) |

| Palau | 36 | 0.90 (0.03) | 0.0028 (0.0018) |

| Moorea | 31 | 0.78 (0.08) | 0.0030 (0.0019) |

| Christmas Island | 51 | 0.85 (0.03) | 0.0025 (0.0016) |

| Cocos Islands | 32 | 0.88 (0.04) | 0.0030 (0.0019) |

| Diego Garcia | 32 | 0.85 (0.05) | 0.0030 (0.0017) |

| Seychelles | 32 | 0.72 (0.07) | 0.0017 (0.0012) |

| Total | 560 | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.0032 (0.0020) |

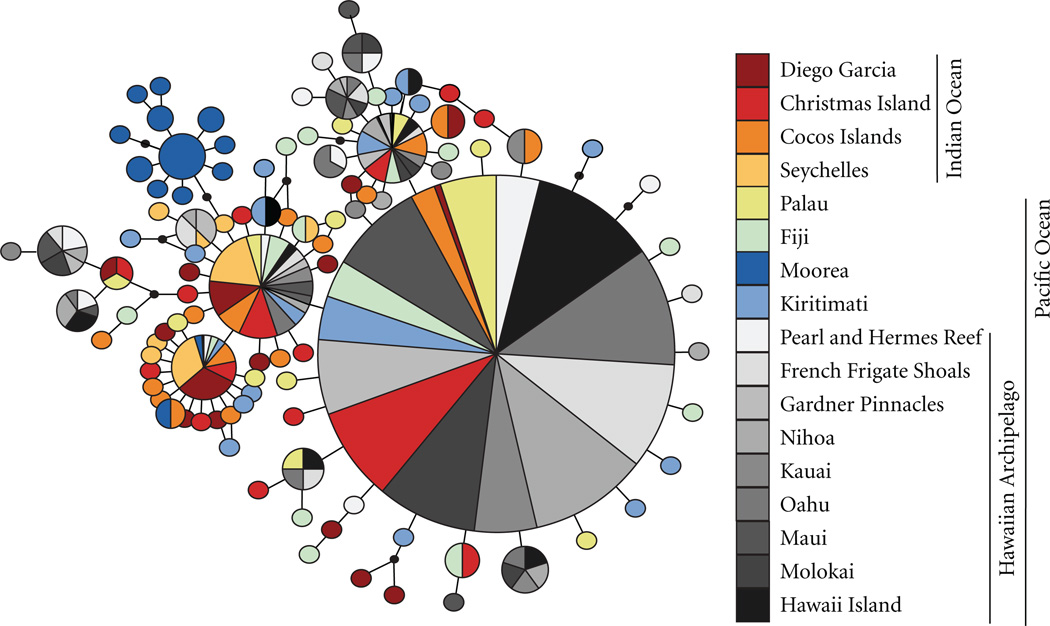

The statistical parsimony network demonstrates both the high diversity and low differentiation of haplotypes collected from sites distributed across two ocean basins (Figure 2). Abundant haplotypes are well dispersed through most sites with the exception of Moorea in French Polynesia, which exhibited a high number of geographically restricted haplotypes.

Figure 2.

Statistical parsimony network for the Brown Surgeonfish. Area of circles is proportional to the frequency of the respective haplotype. Black dots represent missing haplotypes and colors represent haplotype location (see key). (1,200 km northeast of Moorea) where it is either very rare or absent (M. Gaither pers. comm.). Gaither et al. [68] argued that population and community level differences between Moorea (Society Islands) and the Marquesas resulted from limited dispersal across the fast flowing Southern Equatorial Current (SEC), a proposal consistent with recent evidence indicating that ocean currents can have a strong influence on population connectivity [99, 100]. Considering that the Society Islands are located below the westward flowing SEC and within the southerly flowing South Pacific Current [101], oceanographic isolation may likewise explain the concordant break between Moorea and other central Pacific sampling sites observed in both the Bluestriped Snapper and Brown Surgeonfish.

Samova identified three maximally differentiated groupings, with significant population differentiation occurring only at eastern and western edges of the range (Φct = 0.452, P < .001; Table 2). Central Indo-Pacific collections (Cocos Islands to Hawaii) form one large group, while Moorea is isolated in the South Pacific and Diego Garcia is grouped with the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean (Figure 1). Estimates among group differentiations (Φct) dropped incrementally with the addition of K > 3 populations (data not shown) indicating a lack of further population subdivision. Pairwise Φst and Dest highlight both the isolation of Moorea as well as a pattern of increasing divergence in the Indian Ocean with distance from the IPB (Table 3). Both the Seychelles and Diego Garcia were significantly different from all other locations, though the test for IBD within this region was nonsignificant (R2 = 0.46, P = .16). Pairwise estimates of Φst within the Samova-defined central Indo-Pacific population were near zero. Nonetheless, there was a clear IBD signature across this broad region (R2 = 0.61, P < .001, slope = 2.0 × 10−5, y-intercept = 0.038) even though Christmas Island, located in the western Indian Ocean, was only marginally different from Hawaiian collections (Φst = 0.007–0.032, P = .030–.246; Dest =−0.04–0.166, P = .016–.618) and was genetically indistinguishable from Kiritibati, Fiji, and Palau.

Table 2.

Structural analysis of molecular variance (Samova) with maximally differentiated groupings for (K = 1 to 3) and percent variation (%Var.) and fixation indices (Φ).

| Number of groups |

Groupings | Among groups | Among samples within groups | Among samples |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΦCT | %Var. | ΦSC | %Var. | ΦST | ||

| 1 | All sites | 0.201‡ | 20.06 | |||

| 2 | Moorea/All other sites | 0.563 | 56.28 | 0.082‡ | 3.59 | 0.599‡ |

| 3 | Moorea/Seychelles, Diego Garcia/All other sites |

0.452‡ | 45.24 | 0.053‡ | 2.91 | 0.481‡ |

Significance represented by:

P≤ .001.

Table 3.

Results of pairwise tests for population structure with Φst (below diagonal) and Dest (above diagonal).

| PHR | FFS | GAR | Nihoa | Kauai | Oahu | MOL | Maui | HAW | KIR | Fiji | Palau | Moorea | CHR | COC | DEG | SEY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHR | ∼ | 0.031 | 0.059 | 0.032 | −0.005 | 0.015 | 0.015 | −0.020 | 0.059 | 0.225 | 0.098 | 0.028 | 0.982‡ | 0.021 | 0.319* | 0.611‡ | 0.695‡ |

| FFS | 0.033 | ∼ | −0.031 | −0.004 | 0.008 | −0.030 | −0.040 | −0.036 | −0.005 | 0.341‡ | 0.267† | 0.187* | 0.988‡ | 0.134* | 0.461‡ | 0.805‡ | 0.828‡ |

| GAR | 0.020 | −0.025 | ∼ | −0.053 | −0.034 | −0.021 | −0.044 | −0.020 | 0.007 | 0.151 | 0.135 | 0.114 | 0.967‡ | 0.062 | 0.283 | 0.818‡ | 0.816‡ |

| Nihoa | 0.007 | −0.001 | −0.013 | ∼ | −0.022 | −0.026 | −0.045 | −0.023 | −0.023 | 0.200* | 0.184* | 0.147* | 0.971‡ | 0.099 | 0.348† | 0.862‡ | 0.887‡ |

| Kauai | 0.022 | −0.015 | −0.022 | −0.017 | ∼ | −0.029 | −0.027 | −0.052 | 0.046 | 0.062 | −0.001 | 0.008 | 0.970‡ | −0.041 | 0.148 | 0.674‡ | 0.675‡ |

| Oahu | 0.027 | −0.007 | −0.010 | −0.008 | −0.024 | ∼ | −0.049 | −0.034 | −0.027 | 0.258† | 0.195* | 0.139* | 0.981‡ | 0.079 | 0.362‡ | 0.763‡ | 0.775‡ |

| MOL | 0.017 | −0.009 | −0.013 | −0.018 | −0.026 | −0.018 | ∼ | −0.053 | −0.027 | 0.260* | 0.218* | 0.165* | 0.978‡ | 0.106 | 0.397† | 0.837‡ | 0.868‡ |

| Maui | 0.008 | −0.007 | −0.013 | −0.015 | −0.019 | −0.008 | −0.021 | ∼ | 0.019 | 0.234* | 0.168* | 0.130 | 0.980‡ | 0.072 | 0.345† | 0.762‡ | 0.781‡ |

| HAW | 0.006 | 0.000 | −0.002 | −0.015 | −0.005 | −0.003 | −0.010 | 0.002 | ∼ | 0.333† | 0.296† | 0.219† | 0.983‡ | 0.165* | 0.473‡ | 0.859‡ | 0.895‡ |

| KIR | 0.037 | 0.016 | −0.001 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.016 | 0.027 | ∼ | −0.124 | −0.014 | 0.943‡ | 0.012 | −0.068 | 0.623‡ | 0.628‡ |

| Fiji | 0.016 | 0.004 | −0.010 | 0.007 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.010 | −0.012 | ∼ | −0.085 | 0.953‡ | −0.078 | −0.097 | 0.477‡ | 0.496‡ |

| Palau | 0.027 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.040* | 0.026 | 0.040* | 0.041* | 0.040* | 0.029 | 0.003 | −0.007 | ∼ | 0.947‡ | −0.058 | 0.002 | 0.381† | 0.486‡ |

| Moorea | 0.497‡ | 0.615‡ | 0.611‡ | 0.599‡ | 0.608‡ | 0.644‡ | 0.609‡ | 0.582‡ | 0.608‡ | 0.563‡ | 0.554‡ | 0.566‡ | ∼ | 0.960‡ | 0.930‡ | 0.952‡ | 0.960‡ |

| CHR | 0.029 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.031* | 0.015 | 0.030* | 0.033* | 0.031* | 0.022 | −0.002 | −0.010 | −0.012 | 0.583‡ | ∼ | 0.024 | 0.444‡ | 0.472‡ |

| COC | 0.051* | 0.091‡ | 0.073* | 0.100‡ | 0.085‡ | 0.117‡ | 0.110‡ | 0.092‡ | 0.101‡ | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.536‡ | 0.012 | ∼ | 0.304* | 0.318† |

| DEG | 0.174‡ | 0.288‡ | 0.281‡ | 0.295‡ | 0.292‡ | 0.335‡ | 0.310‡ | 0.278‡ | 0.293‡ | 0.187‡ | 0.189‡ | 0.146‡ | 0.538‡ | 0.172‡ | 0.065† | ∼ | 0.022 |

| SEY | 0.240‡ | 0.355‡ | 0.357‡ | 0.359‡ | 0.369‡ | 0.407‡ | 0.385‡ | 0.339‡ | 0.366‡ | 0.236‡ | 0.244‡ | 0.196‡ | 0.583‡ | 0.218‡ | 0.101† | −0.010 | ∼ |

Significance represented by:

for P < .05,

for P < .01,

for P < .001, and bold for P ≤ .0004 (Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). Location abbreviations as described in Figure 1.

Tests for demographic expansion were run on the three Samova populations. While a significant deviation between simulated and observed mismatch distributions was observed only in the Moorean collection (SSD = 0.173, P = .01), Fu’s Fs was significantly negative in all three populations (Table 4). Simulations have shown Fs to be more sensitive to recent population expansion than other tests of demographic history [91], so we place greater emphasis on these tests as indicators of population expansion. Mismatch analyses indicate the time since last expansion to be on the order of 56,000 and 24,000 years in Moorea and the Seychelles/Diego Garcia, respectively, and 83,000 years in the central Indo-Pacific (Table 4). Estimates of post-expansion female effective population size derived from θ1 were unresolved in both the Seychelles and Moorea, but was approximately 300,000 in the central Indo-Pacific population (Table 4).

Table 4.

Estimates of historical demography including pre- and post-expansion theta (θ0 and θ1), female effective population size (Nef), mismatch analyses (sum of squared deviations; SSD), tau (τ), time since last bottleneck (age in years), and test for population expansion (Fs), with unresolved values shown as NR. Standard deviations for population parameter estimates are given in parentheses.

| Mismatch distribution | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMOVA populations |

θ0 | Nef0 | θ1 | Nef1 | SSD | t | Age | Fs |

| Central Indo-Pacific |

0.014 (0–0.745) |

130 (0–7,000) |

30.57 (4.47–NR) |

284,000 (42,000–NR) |

0.003 | 1.78 (0.82–2.52) |

83,000 (38,000–117,000) |

−26.73‡ |

| Moorea | 0.000 (0–0.105) |

0 (0–1,000) |

NR (6.02–NR) |

NR (56,000–NR) |

0.173* | 1.20 (0.37–2.05) |

56,000 (17,000–95,000) |

−9.38‡ |

| Seychelles/Diego Garcia |

0.009 (0–0.345) |

100 (0–3,000) |

NR (2.60–NR) |

NR (24,000–NR) |

0.002 | 0.52 (0.02–1.12) |

24,000 (1,000–52,000) |

−5.74‡ |

Significance represented by:

P≤ .05,

P≤ .001.

4. Discussion

Several patterns are apparent from the phylogeographic assessment of the Brown Surgeonfish. First, populations are characterized by clusters of closely related haplotypes, high haplotype diversity and low nucleotide diversity, a common pattern in reef fishes (Figure 2, Table 1; [94]). Second, Samova and pairwise Φst and Dest indicate that distances as long as 11,000 km do not appear to be much of an obstacle to gene flow in the Brown Surgeonfish (Table 3). Kiribati and Fiji are located at 11,900 and 8,800 km, respectively from Cocos Islands in the Eastern Indian Ocean, yet there were no indications of population differentiation across this large expanse of interspersed islands and reefs. Third, Fu’s Fs and coalescence estimates indicate population contractions throughout the Brown Surgeonfish’s range during the most recent glacial period (∼110–10 ka [95]), with subsequent population expansion, and in turn, increasing genetic diversity (Table 4).

Genetic evidence of postglacial population expansion is common in reef fishes and indicates broad ecosystem level responses to global climate change [94]. These patterns also demonstrate the temporal durability of historical genetic signals and the difficulty extrapolating demographically meaningful estimates of connectivity from genetic data. In particular, population expansion can prolong the time required for populations to reach equilibrium between the forces adding and culling genetic diversity, potentially resulting in an overestimate of population connectivity [96]. There is, however, a negative correlation between rates of gene flow and the time required for populations to attain equilibrium, meaning that well-connected populations will reach equilibrium, and therefore return accurate connectivity estimates, more rapidly than similar populations that are less well connected [90, 97]. Accordingly, while evidence of population expansion in the Brown Surgeonfish may indicate that population connectivity across the central Indo-Pacific may be overestimated, the presence of highly differentiated populations at the edge of the species range (Table 2) demonstrates ample opportunity for the establishment of genetic differentiation within the central Indo-Pacific should gene flow be truly restricted across this region. Likewise, the presence of an IBD signature within the central Indo-Pacific argues against the overestimation of gene flow, as IBD will arise only as populations approach equilibrium [98]. We therefore conclude that the lack of genetic differentiation observed across the majority of the Brown Surgeonfish’s range is indicative of high population connectivity rather than a temporal artifact of nonequilibrium conditions.

The population structure of the Brown Surgeonfish is remarkably similar to the widely distributed Bluestriped Snapper (Lutjanus kasmira), which differs only in having an additional genetic break between Moorea and the Marquesas [68]. Notably, the Brown Surgeonfish is abundant throughout French Polynesia with the exception of the Marquesas

The lack of pronounced mtDNA genetic structure across the central Indo-Pacific in both the Brown Surgeonfish and Bluestriped Snapper has been observed in a growing number of widely distributed reef fishes. Of the six published genetic surveys of reef fishes with geographic ranges extending from Africa to the East Pacific (27,000 km), all but the Convict Surgeonfish (Acanthurus triostegus) revealed little to no genetic subdivision within the Central and West Pacific [56, 68, 102–105]. Remarkably, there was no evidence of population subdivision in the Blue-spine Surgeonfish (Naso unicornis) from the West Indian Ocean to French Polynesia in the South Pacific [104], in the trumpetfish, (Aulostomus chinensis,) from West Australia to Panama [102], and in the Yellow-edged Moray (Gymnothorax flavimarginatus) from East Africa to the East Pacific [105].

The broad genetic connectivity consistently observed in the most widely distributed Indo-Pacific fishes highlights an emerging relationship between reef fish range size and genetic connectivity. In particular, Soldierfishes (genus Myripristis [24, 56]), Pygmy Angelfishes (genus Centropyge [106, 107]), Trumpetfishes (genus Aulostomus [102]), Unicornfishes (genus Naso [104, 108]), Moray Eels (genus Gymnothorax [105]), and at least some Snappers (genus Lutjanus [68]) and Surgeonfishes (genus Acanthurus [31, 109]) have demonstrated an ability to maintain genetic homogeneity across tens of thousands of kilometers.

For widely distributed species, genetic homogeneity across much of the Indo-Pacific is largely concordant with biogeographic provinces and barriers, previously defined based on species distributions. For example, the region stretching from the eastern Indian Ocean to the Central Pacific is recognized by biogeographers as the Indo-Polynesian province [110–112]. Hobbes et al. [113] observed that many Indian and Pacific reef fishes overlap at our sample location in the Eastern Indian Ocean (Christmas Island), and in some cases hybridize there. For large-range fishes, this location is commonly the western limit of a broad central Indo-Pacific population, and hence demonstrates the alignment of intraspecific phylogeographic patterns with biogeographic provinces.

This pattern of widely distributed reef fishes successfully bridging long-distances contrasts starkly with the remarkably complex patterns of population structure commonly observed in smaller range fishes. The leopard coral grouper (Plectropomus leopardus) is restricted to reefs from West Australia to Fiji, and a survey of mtDNA control region diversity indicated deep genetic partitions, with a minimum of six highly differentiated populations (Fst = 0.90 to 0.94 [114]). Likewise, a comparative mtDNA survey of three restricted-range Damselfishes (Amphiprion melanopus, Chrysiptera talboti and Pomacentrus moluccensis) and the restricted-range Wrasse, (Cirrhilabrus punctatus,) revealed concordant morphological and genetic differentiation, and indicates evolutionary level partitions among the closely linked reefs of the West Pacific [115]. Small range species with planktonic larval dispersal and pronounced mtDNA population subdivision appear to be particularly common in Damselfishes (genus Amphiprion [115–117]; genus Chrysiptera [115, 118]; genus Dascyllus [57, 119]; genus Pomacentrus [119]), and Groupers (genus Epinephelus [55, 114]; genus Plectropomus [114]).

For species occurring within the central Indo-Pacific, broad genetic homogeneity should be facilitated by stepping stone gene flow across the regions relatively abundant reefs. Indeed, dispersal can be accomplished across this vast region without having to traverse more than 800 km of open ocean [120], yet even these relatively limited distances act as effective barriers to gene flow in many smaller range fishes (e.g., [114]). Conversely, the limited genetic subdivision commonly observed in widely distributed species indicate larval exchange across thousands of kilometers of open ocean, including across the world’s largest marine biogeographic barrier, the Eastern Pacific Barrier (EPB [63, 121, 122]. The EPB comprises the 4,000 to 7,000 km expanse of open ocean separating the islands of the Central Pacific from the west coast of the Americas. The suite of species demonstrating recent or ongoing larval connectivity across the EPB contains members of the most common Indo-Pacific reef fish families, though notably absent are Damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and Groupers (Serranidae), identified above as taxanomic families with limited individual and geographic range.

It has been noted that mtDNA markers may not accurately reflect population histories, due to either direct selection on the marker or adjacent DNA segments [123]. However, when comparing genetic partitions among multiple species, matching patterns indicates such concerns are likely unwarranted since the biological or environmental mechanisms that drive concordance across species will likewise drive concordance across markers [70]. A notable exception to this rule is sex-biased dispersal [124, 125], though this is unlikely to be an issue in species with pelagic larval dispersal [68]. Accordingly, the broad agreement between biogeographic and phylogeographic patterns herein demonstrates that species differ in dispersal ability at biogeographic and evolutionary time-scales, which in turn would appear to indicate that species differ in the extent and magnitude of population connectivity at demographic and ecological time-scales.

How do these findings translate into policies for ecosystem-level management of reef communities? The debate continues over the extent to which genetic connectivity relates to demographic connectivity [126]. Further application of larval tracking will help identify the degree to which species and regions may differ in the scale and extent of larval exchange. However, until that time, the apparent relationship between reef fish range size and extent of genetic connectivity indicates that recent evidence of high local larval retention may only apply to species with small geographic ranges. In all likelihood, marine communities contain species with markedly different dispersal abilities [127–129], including many capable of larval exchange over thousands of kilometers.

While interspecific differences in realized dispersal would appear to complicate the development of effective marine reserves, reserve design may be simplified by focusing on the species that show the finest scale of genetic isolation [69, 130, 131]. Emphasis on short-distance dispersers requires protecting reefs on a local scale, resulting in the establishment of a network of smaller reserves [129]. While setting aside one or a few larger reserves might be politically more expedient than placing an equivalent area under protection with multiple small reserves [132], a network of smaller reserves would better accommodate differences in dispersal ability among resident species by facilitating linkages among reserves at multiple spatial scales. Under this scenario, protected populations would be sustained by either local retention within the reserve or dispersal between adjacent reserves for short to moderate dispersing species, and by larval exchange between distant reserves for widely dispersing species. Additionally, a network of smaller reserves would maximize opportunities for larval subsidy to unprotected populations by increasing the likelihood of seeding reefs outside of reserve boundaries [133], one of the primary goals of reserves designed to mitigate fisheries impacts [134]. No matter the management strategy employed, overcoming the challenges of incorporating multiscale connectivity patterns into resource management planning will ultimately help ensure long-term resource stability by preserving communities of species that differ markedly in how they respond to local and global environmental impacts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, British Indian Ocean Territory, Seychelles Fishing Authority, Seychelles Bureau of Standards, Coral Reef Research Foundation, and Pulu Keeling National Park for coordinating research activities and permitting procedures. Special thanks to the crew of the NOAA Ship “Hi’ialakai”, T. Daly-Engel, C. Bird, C. Sheppard, A. Alexander, R. Kosaki, C. Musberger, S. Karl, C. Meyer, M. Gaither, M. Iacchei, Z. Szabo, J. Drew, D. Pence, Y. Papastamatiou, B. Victor, J. H. Choat, R. “Greenie” Thorn, I. Macrae, P. Colin, L. Colin, M. Mesubed, E. Basilius, B. Walsh, L. Basch, J. Zamzow, I. Williams, J. Earle, R. Pyle, L. Sorensen, D. White, G. Concepcion, D. Skillings, J. Drew, J. Robinson, J. Mortimer, K. Andersen, B. Yeeting, E. Tekaraba, K. Flanagan and all members of the ToBo lab for field collections, laboratory assistance, and valuable advice. This paper was funded by US National Science Foundation Grants to B. W. B. and R. J. T. (OCE-0454873, OCE-0453167, OCE-0623678, and OCE-0929031) and to the UH EECB program (OCE-0232016), in conjunction with the HIMB-NWHI Coral Reef Research Partnership (NMSP MOA 2005-008/6682) and Cocos and Christmas Island collection support from National Geographic Society grant to M.T.C. (8208-07). We thank the staff of the HIMB Core Facility for sequencing (EPS-0554657). This paper complies with current laws in the United States and was conducted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Hawaii Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

References

- 1.Dayton PK, Thrush SF, Agardy MT, Hofman RJ. Environmental effects of marine fishing. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 1995;5(3):205–232. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson JBC, Kirby MX, Berger WH, et al. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science. 2001;293(5530):629–637. doi: 10.1126/science.1059199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandolfi JM, Bradbury RH, Sala E, et al. Global trajectories of the long-term decline of coral reef ecosystems. Science. 2003;301(5635):955–958. doi: 10.1126/science.1085706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halpern BS, Warner RR. Marine reserves have rapid and lasting effects. Ecology Letters. 2002;5(3):361–366. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauly D, Christensen V, Guénette S, et al. Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature. 2002;418(6898):689–695. doi: 10.1038/nature01017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gell FR, Roberts CM. Benefits beyond boundaries: the fishery effects of marine reserves. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2003;18(9):448–455. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubchenco J, Palumbi SR, Gaines SD, Andelman S. Plugging a hole in the ocean: the emerging science of marine reserves. Ecological Applications. 2003;13(1):S3–S7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guichard F, Levin SA, Hastings A, Siegel D. Toward a dynamic metacommunity approach to marine reserve theory. BioScience. 2004;54(11):1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes TP, Bellwood DR, Folke C, Steneck RS, Wilson J. New paradigms for supporting the resilience of marine ecosystems. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2005;20(7):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dugan JE, Davis GE. Applications of marine refugia to coastal fisheries management. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 1993;50(9):2029–2042. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sale PF, Cowen RK, Danilowicz BS, et al. Critical science gaps impede use of no-take fishery reserves. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2005;20(2):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Botsford LW, White JW, Coffroth M-A, et al. Connectivity and resilience of coral reef metapopulations in marine protected areas: matching empirical efforts to predictive needs. Coral Reefs. 2009;28(2):327–337. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0466-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones GP, Millcich MJ, Emsile MJ, Lunow C. Self-recruitment in a coral fish population. Nature. 1999;402(6763):802–804. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Planes S, Jones GP, Thorrold SR. Larval dispersal connects fish populations in a network of marine protected areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(14):5693–5697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808007106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crisp DJ. Overview of research on marine invertebrate larvae. In: Costlow JD, Tipper RC, editors. Marine Biodeterioration: An Interdisciplinary Study. Annapolis, Md, USA: Naval Institute Press; 1984. pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strathmann RR. Hypotheses on the origins of marine larvae. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1993;24:89–117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanks AL, Grantham BA, Carr MH. Propagule dispersal distance and the size and spacing of marine reserves. Ecological Applications. 2003;13(1):S159–S169. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanks AL. Pelagic larval duration and dispersal distance revisited. The Biological Bulletin. 2009;216(3):373–385. doi: 10.1086/BBLv216n3p373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel DA, Kinlan BP, Gaylord B, Gaines SD. Lagrangian descriptions of marine larval dispersion. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2003;260:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lester SE, Ruttenberg BI. The relationship between pelagic larval duration and range size in tropical reef fishes: a synthetic analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2005;272(1563):585–591. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weersing K, Toonen RJ. Population genetics larval dispersal, and connectivity in marine systems, Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2009;393:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leis JM, McCormick MI. The biology, behavior and ecology of the pelagic larval stage of coral reef fishes. In: Sale PF, editor. Coral Reef Fishes: Dynamics and Diversity in a Complex Ecosystem. San Diego, Calif, USA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 171–199. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Underwood JN, Smith LD, van Oppen MJH, Gilmour JP. Ecologically relevant dispersal of corals on isolated reefs: implications for managing resilience. Ecological Applications. 2009;19(1):18–29. doi: 10.1890/07-1461.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowen BW, Bass AL, Muss A, Carlin J, Robertson DR. Phylogeography of two Atlantic squirrelfishes (family Holocentridae): exploring links between pelagic larval duration and population connectivity. Marine Biology. 2006;149(4):899–913. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones AG, Moore GI, Kvarnemo C, Walker D, Avise JC. Sympatric speciation as a consequence of male pregnancy in seahorses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(11):6598–6603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131969100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocha LA, Robertson DR, Roman J, Bowen BW. Ecological speciation in tropical reef fishes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2005;272(1563):573–579. doi: 10.1098/2004.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choat JH. Phylogeography and reef fishes: bringing ecology back into the argument. Journal of Biogeography. 2006;33(6):967–968. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocha LA, Bowen BW. Speciation in coral-reef fishes. Journal of Fish Biology. 2008;72(5):1101–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crow KD, Munehara H, Bernardi G. Sympatric speciation in a genus of marine reef fishes. Molecular Ecology. 2010;19(10):2089–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farnsworth CA, Bellwood DR, van Herwerden L. Genetic structure across the GBR: evidence from shortlived gobies. Marine Biology. 2010;157(5):945–953. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocha LA, Bass AL, Robertson DR, Bowen BW. Adult habitat preferences, larval dispersal, */89+.36, and the comparative phylogeography of three Atlantic surgeonfishes (Teleostei: Acanthuridae), Molecular Ecology. 2002;11(2):243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellwood DR, Fisher R. Relative swimming speeds in reef fish larvae. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2001;211:299–303. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerlach G, Atema J, Kingsford MJ, Black KP, Miller-Sims V. Smelling home can prevent dispersal of reef fish larvae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(3):858–863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606777104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowen RK, Sponaugle S. Larval dispersal and marine population connectivity. Annual Review of Marine Science. 2009;1:443–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swearer SE, Caselle JE, Lea DW, Warner RR. Larval retention and recruitment in an island population of a coral-reef fish. Nature. 1999;402(6763):799–802. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones GP, Planes S, Thorrold SR. Coral reef fish larvae settle close to home. Current Biology. 2005;15(14):1314–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almany GR, Berumen ML, Thorrold SR, Planes S, Jones GP. Local replenishment of coral reef fish populations in a marine reserve. Science. 2007;316(5825):742–744. doi: 10.1126/science.1140597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson HM, Swearer SE. Long-distance dispersal and local retention of larvae as mechanisms of recruitment in an island population of a coral reef fish. Austral Ecology. 2007;32(2):122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carreras-Carbonell J, Macpherson E, Pascual M. High self-recruitment levels in a Mediterranean littoral fish population revealed by microsatellite markers. Marine Biology. 2007;151(2):719–727. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doherty PJ, Williams DM. The replenishment of coral reef populations. Oceanography and Marine Biology. 1988;26:487–551. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sale PF. Reef fish communities: open nonequilibrium systems. In: Sale PF, editor. The Ecology of Fishes on Coral Reefs. San Diego, Calif, USA: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 564–598. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caley MJ, Carr MH, Hixon MA, Hughes TP, Jones GP, Menge BA. Recruitment and the local dynamics of open marine populations. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1996;27:477–500. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doherty P, Fowler T. An empirical test of recruitment limitation in a coral reef fish. Science. 1994;263(5149):935–939. doi: 10.1126/science.263.5149.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones GP, Almany GR, Russ GR, et al. Larval retention connectivity among populations of corals and reef fishes: history, advances and challenges, Coral Reefs. 2009;28(2):307–325. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jablonski D, Lutz RA. Larval ecology of marine ben-thic invertebrates: paleobiological implications. Biological Reviews. 1983;58(1):21–89. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown JH, Stevens GC, Kaufman DM. The geographic range: size, shape, boundaries, and internal structure, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1996;27:597–623. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mora C, Robertson DR. Causes of latitudinal gradients in species richness: a test with fishes of the tropical eastern pacific. Ecology. 2005;86(7):1771–1782. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paulay G, Meyer C. Dispersal and divergence across the greatest ocean region: do larvae matter? Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2006;46(3):269–281. doi: 10.1093/icb/icj027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wellington GM, Victor BC. Planktonic larval duration of one hundred species of Pacific and Atlantic damselfishes (Pomacentridae) Marine Biology. 1989;101(4):557–567. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lester SE, Ruttenberg BI, Gaines SD, Kinlan BP. The relationship between dispersal ability and geographic range size. Ecology Letters. 2007;10(8):745–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinlan BP, Gaines SD. Propagule dispersal in marine and terrestrial environments: a community perspective. Ecology. 2003;84(8):2007–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradbury IR, Bentzen P. Non-linear genetic isolation by distance: implications for dispersal estimation in anadro-mous and marine fish populations. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;340:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jablonski D. Larval ecology and macroevolution in marine invertebrates. Bulletin of Marine Science. 1986;39(2):565–587. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emlet RB. Developmental mode and species geographic range in regular sea urchins (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) Evolution. 1995;49(3):476–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rivera MAJ, Kelley CD, Roderick GK. Subtle population genetic structure in the Hawaiian grouper, Epinephelus quernus (Serranidae) as revealed by mitochondrial DNA analyses, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2004;81(3):449–468. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Craig MT, Eble JA, Bowen BW, Robertson DR. High genetic connectivity across the Indian and Pacific Oceans in the reef fish Myripristis berndti (Holocentridae) Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;334:245–254. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramon ML, Nelson PA, De Martini E, Walsh WJ, Bernardi G. Phylogeography historical demography, and the role of post-settlement ecology in two Hawaiian damselfish species, Marine Biology. 2008;153(6):1207–1217. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eble JA, Toonen RJ, Bowen BW. Endemism and dispersal: comparative phylogeography of three surgeon-fishes across the Hawaiian Archipelago. Marine Biology. 2009;156(4):689–698. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Craig MT, Eble JA, W Bowen B. Origins, ages, and population histories: comparative phylogeography of endemic Hawaiian butterflyfishes (genus Chaetodon), Journal of Biogeography. 2010;37:2125–2136. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fishelson L, Montgomery AH, Myrberg AH., Jr Biology of the surgeonfish Acanthurus nigrofuscus with emphasis on change over in diet and gonadal cycles. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1987;39:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Domeier ML, Colin PL. Tropical reef fish spawning aggregations: defined and reviewed. Bulletin of Marine Science. 1997;60(3):698–726. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Randall JE. Reef and Shore Fishes of the South Pacific: New Caledonia to Tahiti and the Pitcairn Islands. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA: University of Hawaii Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Briggs JC. Marine Zoogeography. New York, NY, USA: McGraw–Hill; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Randall JE. Reef and Shore Fishes of the Hawaiian Islands. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA: University of Hawaii Sea Grant Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lessios HA. The great American schism: divergence of marine organisms after the rise of the Central american Isthmus. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2008;39:63–91. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daly-Engel TS, Grubbs RD, Feldheim KA, Bowen BW, Toonen RJ. Is multiple mating beneficial or unavoidable? Low multiple paternity and genetic diversity in the shortspine spurdog Squalus mitsukurii. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2010;403:255–267. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bohonak AJ. Dispersal gene flow, and population structure, Quarterly Review of Biology. 1999;74(1):21–45. doi: 10.1086/392950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gaither MR, Toonen RJ, Robertson DR, Planes S, Bowen BW. Genetic evaluation of marine biogeographic barriers: perspectives from two widespread Indo-Pacific snappers (Lutjanus spp.) Journal of Biogeography. 2010;37(1):133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toonen RJ, Andrews KR, Baums IB. Defining boundaries for Ecosystem-based management: a multi-species case study of marine connectivity across the Hawaiian Archipelago. Journal of Marine Biology. doi: 10.1155/2011/460173. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Avise JC. Molecular Markers, Natural History, and eEvolution. Sunderland, Mass, USA: Sinauer Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hellberg ME, Burton RS, Neigel JE, Palumbi SR. Genetic assessment of connectivity among marine populations. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2002;70(1):273–290. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lowe WH, Allendorf FW. What can genetics tell us about population connectivity? Molecular Ecology. 2010;19(15):3038–3051. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rousset F. Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics. 1997;145(4):1219–1228. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Waples RS. Separating the wheat from the chaff: patterns of genetic differentiation in high gene flow species. Journal of Heredity. 1998;89(5):438–450. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Waples RS, Gaggiotti O. What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity. Molecular Ecology. 2006;15(6):1419–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luikart G, England PR, Tallmon D, Jordan S, Taber-let P. The power and promise of population genomics: from genotyping to genome typing. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2003;4(12):981–994. doi: 10.1038/nrg1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sunnucks P, Hales DF. Numerous transposed sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I-II in aphids of the genus Sitobion (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1996;13(3):510–524. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song CB, Near TJ, Page LM. Phylogenetic Relations among Percid Fishes as Inferred from Mitochondrial Cytochrome b DNA Sequence Data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1998;10(3):343–353. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Taberlet P, Meyer A, Bouvert J. Unusually large mitochondrial variation in populations of the blue tit, Parus caeruleus. Molecular Ecology. 1992;1:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1992.tb00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K-I, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30(14):3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Excoffier L, Laval LG, Schneider S. Arlequin ver 3.0: an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Biology Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nei M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. New York, NY, USA: Columbia University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clement M, Posada D, Crandall KA. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9(10):1657–1659. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dupanloup I, Schneider S, Excoffier L. A simulated annealing approach to define the genetic structure of populations. Molecular Ecology. 2002;11(12):2571–2581. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1993;10(3):512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Akaike H. A new look at statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19(6):716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14(9):817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jost L. GST and its relatives do not measure differentiation. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17(18):4015–4026. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2008.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wright S. Isolation by distance. Genetics. 1943;28:114–138. doi: 10.1093/genetics/28.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Slatkin M. Isolation by distance in equilibrium and nonequilibrium populations. Evolution. 1993;47:264–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fu Y-X. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection, Genetics. 1997;147(2):915–925. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hart AM, Russ GR. Response of herbivorous fishes to crown-of-thorns starfish Acanthaster planci outbreaks. III. Age, growth, mortality and maturity indices of Acanthurus nigrofuscus. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1996;136(1–3):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lessios HA. The great American schism: divergence of marine organisms after the rise of the Central american Isthmus. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2008;39:63–91. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grant WS, Bowen BW. Shallow population histories in deep evolutionary lineages of marine fishes: insights from sardines and anchovies and lessons for conservation. Journal of Heredity. 1998;89(5):415–426. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Benn DI, Evans DJA. Glaciers and Glaciation. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ibrahim KM, Nichols RA, Hewitt GM. Spatial patterns of genetic variation generated by different forms of dispersal during range expansion. Heredity. 1996;77(3):282–291. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bradbury IR, Bentzen P. Non-linear genetic isolation by distance: implications for dispersal estimation in anadro-mous and marine fish populations. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;340:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hutchison DW, Templeton AR. Correlation of pair-wise genetic and geographic distance measures: inferring the relative influences of gene flow and drift on the distribution of genetic variability. Evolution. 1999;53(6):1898–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb04571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cudney-Bueno R, Lavín MF, Marinone SG, Raimondi PT, Shaw WW. Rapid effects of marine reserves via larval dispersal. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004140. Article ID e4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.White C, Selkoe KA, Watson J, Siegel DA, Zacherl DC, Toonen RJ. Ocean currents help explain population genetic structure. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2010;277(1688):1685–1694. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bonjean F, Lagerloef GSE. Diagnostic model and analysis of the surface currents in the Tropical Pacific Ocean. Journal of Physical Oceanography. 2002;32(10):2938–2954. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bowen BW, Bass AL, Rocha LA, Grant WS, Robertson DR. Phylogeography of the trumpetfishes (Aulostomus): ring species complex on a global scale. Evolution. 2001;55(5):1029–1039. doi: 10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[1029:pottar]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Planes S, Fauvelot C. Isolation by distance and vicariance drive genetic structure of a coral reef fish in the Pacific Ocean. Evolution. 2002;56(2):378–399. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Horne JB, van Herwerden L, Choat JH, Robertson DR. High population connectivity across the Indo-Pacific: congruent lack of phylogeographic structure in three reef fish congeners. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2008;49(2):629–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Reece JS, Bowen BW, Joshi K, Goz V, Larson A. Phylogeography of two moray eels indicates high dispersal throughout the INDO-PACIFIC. Journal of Heredity. 2010;101(4):391–402. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esq036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schultz JK, Pyle RL, DeMartini E, Bowen BW. Genetic connectivity among color morphs Pacific archipelagos for the flame angelfish, Centropyge loriculus. Marine Biology. 2007;151(1):167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bowen BW, Muss A, Rocha LA, Grant WS. Shallow mtDNA coalescence in Atlantic pygmy angelfishes (genus Centropyge) indicates a recent invasion from the Indian Ocean. Journal of Heredity. 2006;97(1):1–12. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esj006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Klanten OS, Choat JH, Van Herwerden L. Extreme genetic diversity and temporal rather than spatial partitioning in a widely distributed coral reef fish. Marine Biology. 2007;150(4):659–670. [Google Scholar]

- 109.DiBattista JD, Wilcox C, Craig MT, Rocha LA, Bowen BW. Phylogeographic survey of the Bluelined surgeonfish, Acanthurus nigroris, reveals high connectivity and a cryptic endemic species in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Journal of Marine Biology. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Briggs JC. Global Biogeography. The Netherlands: Elsevier, Amsterdam; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vernon JEN. Coral in Space and Time. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Randall JE. Zoogeography of shore fishes of the Indo-Pacific region. Zoological Studies. 1998;37(4):227–268. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hobbs JA, Frisch AJ, Allen GR, Van Herwerden L. Marine hybrid hotspot at Indo-Pacific biogeographic border. Biology Letters. 2009;5(2):258–261. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.van Herwerden L, Choat JH, Newman SJ, Leray M, Hillersøy G. Complex patterns of population structure and recruitment of Plectropomus leopardus (Pisces: Epinephelidae) in the Indo-West Pacific: implications for fisheries management. Marine Biology. 2009;156(8):1595–1607. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Drew J, Allen GR, Kaufman L, Barber PH. Endemism and regional color and genetic differences in five putatively cosmopolitan reef fishes. Conservation Biology. 2008;22(4):965–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Timm J, Figiel M, Kochzius M. Contrasting patterns in species boundaries evolution of anemonefishes (Amphiprioninae, Pomacentridae) in the centre of marine biodiversity, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2008;49(1):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Timm J, Kochzius M. Geological history and oceanography of the Indo-Malay Archipelago shape the genetic population structure in the false clown anemonefish (Amphiprion ocellaris) Molecular Ecology. 2008;17(18):3999–4014. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2008.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Drew JA, Allen GR, Erdmann MV. Congruence between mitochondrial genes color morphs in a coral reef fish: population variability in the Indo-Pacific damselfish Chrysiptera rex (Snyder, 1909), Coral Reefs. 2010;29(2):439–444. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Drew J, Barber PH. Sequential cladogenesis of the reef fish Pomacentrus moluccensis (Pomacentridae) supports the peripheral origin of marine biodiversity in the Indo-Australian archipelago. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2009;53(1):335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schultz JK, Feldheim KA, Gruber SH, Ashley MV, McGovern TM, Bowen BW. Global phylogeography and seascape genetics of the lemon sharks (genus Negaprion) Molecular Ecology. 2008;17(24):5336–5348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ekman S. Zoogeography of the Sea. London, UK: Sidwick & Jackson; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lessios HA, Robertson DR. Crossing the impassable: genetic connections in 20 reef fishes across the eastern Pacific barrier. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273(1598):2201–2208. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bazin E, Glémin S, Galtier N. Population size does not influence mitochondrial genetic diversity in animals. Science. 2006;312(5773):570–572. doi: 10.1126/science.1122033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Prugnolle F, de Meeus T. Inferring sex-biased dispersal from population genetic tools: a review. Heredity. 2002;88(3):161–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bowen BW, Bass AL, Soares L, Toonen RJ. Conservation implications of complex population structure: lessons from the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) Molecular Ecology. 2005;14(8):2389–2402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Christie MR, Johnson DW, Stallings CD, Hixon MA. Self-recruitment and sweepstakes reproduction amid extensive gene flow in a coral-reef fish. Molecular ecology. 2010;19(5):1042–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mora C, Sale PF. Are populations of coral reef fish open or closed? Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2002;17(9):422–428. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kinlan BP, Gaines SD, Lester SE. Propagule dispersal and the scales of marine community process. Diversity and Distributions. 2005;11(2):139–148. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cowen RK, Paris CB, Srinivasan A. Scaling of connectivity in marine populations. Science. 2006;311(5760):522–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1122039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bird CE, Holland BS, Bowen BW, Toonen RJ. Contrasting phylogeography in three endemic Hawaiian limpets (Cellana spp.) with similar life histories. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16(15):3173–3186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Colin PL. Fishes as living tracers of connectivity in the tropical western North Atlantic: Distribution of the neon gobies I. genus Elacatinus (Pisces: Gobiidae), Zootaxa. 2010;2370:36–52. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jones GP, Srinivasan M, Almany GR. Population connectivity and conservation of marine biodiversity. Oceanography. 2007;20:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Roberts CM, Bohnsack JA, Gell F, Hawkins JP, Goodridge R. Effects of marine reserves on adjacent fisheries. Science. 2001;294(5548):1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Halpern BS, Warner RR. Matching marine reserve design to reserve objectives. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2003;270(1527):1871–1878. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]