Abstract

Measures of body condition, immune function, and hematological health are widely used in ecological studies of vertebrate populations, predicated on the assumption that these traits are linked to fitness. However, compelling evidence that these traits actually predict long-term survival and reproductive success among individuals in the wild is lacking. Here, we show that body condition (i.e., size-adjusted body mass) and cutaneous immune responsiveness to phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) injection among neonates positively predict recruitment and subsequent longevity in a wild, migratory population of house wrens (Troglodytes aedon). However, neonates with intermediate hematocrit had the highest recruitment and longevity. Neonates with the highest PHA responsiveness and intermediate hematocrit prior to independence eventually produced the most offspring during their lifetime breeding on the study site. Importantly, the effects of PHA responsiveness and hematocrit were revealed while controlling for variation in body condition, sex, and environmental variation. Thus, our data demonstrate that body condition, cutaneous immune responsiveness, and hematocrit as a neonate are associated with individual fitness. Although hematocrit's effect is more complex than traditionally thought, our results suggest a previously underappreciated role for this trait in influencing survival in the wild.

Keywords: fitness, phytohaemagglutinin, recruitment, survival, Troglodytes aedon

Introduction

A fundamental aim of evolutionary ecology is the identification of traits related to fitness and the processes that shape variation in those traits. Although the physical condition, immune defenses, and health state of organisms are putatively associated with their survival, relationships between these traits and fitness in natural populations are largely unknown. Notwithstanding the logistical constraints in obtaining estimable fitness proxies in wild populations (e.g., lifetime reproductive success), the relationship between phenotype and fitness is elusive because variation in a given trait may have complex effects on survival and reproduction. For example, individuals with better-than-average immunity might be expected to survive better than those with poorer immune systems through increased parasite defenses, but heightened immunity may also reduce longevity and fitness through self-damage (Sheldon and Verhulst 1996, Møller and Saino 2004, Sadd and Siva-Jothy 2006, Graham et al. 2010, Wilcoxen et al. 2010, Guerreiro et al. 2012). Thus, selection should favor optimal rather than maximal immunoresponsiveness, yet what is optimal is seldom clear.

Among the traits typically measured by animal ecologists, body condition is perhaps the most widely used and also the most controversial in its precise meaning and correct estimation (e.g., Packard and Boardman 1988, García-Berthou 2001, Green 2001, Schulte-Hostedde et al. 2005, Schamber et al. 2009). Here we use a common definition of body condition as body mass adjusted for body size (García-Berthou 2001, Ardia 2005c). There is evidence from a number of studies, albeit mixed, that body mass or condition is positively associated with recruitment and survival in local populations (Clutton-Brock et al. 1987, Tinbergen and Boerlijst 1990, Hochachka and Smith 1991, Young 1996, Both et al. 1999). A positive effect of neonatal body condition on survival might be expected if body condition was indicative of lipid reserves that young will need after leaving the nest (e.g., Thompson et al. 1993, Naef-Daenzer et al. 2001, Ardia 2005c), particularly in migratory birds where fledglings have a narrow window of time to learn to fly, avoid predators, and forage for themselves prior to autumn migration (see also Lindström 1999, Mitchell et al. 2011). Indeed, postfledging mortality often imposes an enormous bottleneck for neonates in altricial birds (e.g., Naef-Daenzer et al. 2001, Tarwater et al. 2011). Paradoxically, however, the relationship between mass and survival is not always positive (Lindén et al. 1992, Young 1996, Gaillard et al. 2000, Merilä et al. 2001).

Measures of immune responsiveness and health state are also commonly used in ecological studies, but the relationship between variation in these traits and survival are even less clear than for body condition. Interspecific comparisons provide evidence that immune responsiveness varies with average lifespan (Tella et al. 2002), suggesting a relationship between immunity and longevity. It is unclear, however, whether intraspecific variation in immune responsiveness is associated with individual differences in longevity and lifetime reproductive success within populations (Viney et al. 2005, Nussey et al. 2014). Life-history theory posits that investment in immune function should vary with pace of life (e.g., Martin et al. 2001, Ricklefs and Wikelski 2002, Lee 2006). Typically, general and inflammatory immune defenses against pathogens should be favored in short-lived species with rapid growth, short generation times, and high juvenile mortality, whereas specific and humoral immune responses should be favored in long-lived species with lower juvenile mortality and longer development times (see also Tieleman et al. 2005).

Hematocrit may also contribute significantly to individual fitness. Hematocrit is the fraction of whole blood comprised of erythrocytes and determines an individual's ability to deliver oxygen to tissues. Despite this critical function, results to date have questioned the significance of variation in hematocrit and its relationship with individual quality and fitness in nature (Dawson and Bortolotti 1997, Fair et al. 2006, Norte et al. 2008). Although increased hematocrit promotes the delivery of oxygen to tissues, increasing hematocrit also causes blood viscosity to increase at an increasing rate, which also reduces oxygen delivery (Birchard 1997, Schuler et al. 2010, Williams 2012). Consequently, oxygen transport is reduced in individuals with below-optimal hematocrit because of a reduced ability to carry oxygen, while above-optimal increases in hematocrit lead to disproportionate increases in blood viscosity that also reduce cardiac efficiency. Indeed, above-optimal increases in hematocrit can cause earlier exhaustion during physical activity and increased cardiopulmonary hypertension (Maxwell et al. 1992, Birchard 1997, Schuler et al. 2010, Williams 2012). Thus, variation in hematocrit may actually have a profound but non-linear association with survival in the wild.

In this study, we use a multi-year dataset to test whether body condition (i.e., size-adjusted body mass), cutaneous immune responsiveness, and hematocrit among neonates prior to independence are associated with recruitment, longevity (i.e., number of years as a breeder), and lifetime reproductive success in a wild population of house wrens (Troglodytes aedon). House wrens are short-lived in temperate North America, with most offspring not surviving to adulthood and those that do usually breeding in only one year (Johnson 2014). Consequently, individual house wrens are much less likely than those of longer-lived species to encounter a diverse array of parasite fauna during their lifetime, so mounting non-specific and inflammatory immune responses should be favored heavily in this species (Ricklefs and Wikelski 2002, Lee 2006). Therefore, we used PHA-induced skin swelling as a measure of cutaneous immune responsiveness, which is a general immune response characterized by inflammation and the recruitment of both innate and adaptive components of the immune system (McCorkle et al. 1980, Martin et al. 2006b, Vinkler et al. 2014). Given that house wrens have short lifespans and attempt to produce multiple broods of young within breeding seasons (Johnson 2014; i.e., a live-fast, die-young life history), we predicted that body condition and cutaneous immune responsiveness would be positively correlated with recruitment, longevity, and lifetime reproductive success, whereas the relationship between hematocrit and recruitment and longevity may be non-linear.

Methods

Study species and field procedures

House wrens are small songbirds with a widespread distribution in North America (biology summarized in Johnson 2014). Females lay clutches of four to eight eggs. Only females incubate eggs and brood nestlings, but both parents provision nestlings. Young fledge 14-16 d post-hatching and reach independence within ≈14 d (Bowers et al. 2013, Johnson 2014). We studied a migratory population of house wrens from 2004-2013 in Illinois, USA (40°40'N, 88°53'W). Nestboxes (N = 820; see Lambrechts et al. 2010 for details) were distributed at a density of 5.4 boxes/ha. Dispersal between breeding seasons is limited; on average, the nesting sites of males and females shift 67 and 134 m, respectively, from their location the year before (Drilling and Thompson 1988). There is also a strong preference for nesting in boxes rather than natural tree cavities, with approximately 95% of nests at any given time being in the nestboxes supplied (Drilling and Thompson 1988). Of the 126 recruits we captured, there were 17 that had a “gap year” (i.e., they were captured breeding on the study area in years t and t+2, but not in year t+1); these birds may have (i) been at the study site and bred in a natural cavity that we did not detect, or were present but did not breed that year, or (ii) been in a different geographic location. Reassuringly, whether or not an individual had a gap year was unrelated to any of the variables we measured (all P > 0.1), suggesting that differences in return rate with respect to the traits we measured are attributable primarily to differences in survival and not dispersal. Thus, adults surviving from one year to the next were likely to be captured breeding in our nestboxes at least once during a given breeding season, and failing to detect certain individuals during gap years should add only noise, not a bias, to our results.

Each year we attempted to capture and mark all individuals on the site with numbered leg bands. Nestlings in this study hatched during the 2004-2006 and 2011-2012 breeding seasons. Eleven days after hatching began within nests, we weighed all nestlings (±0.1 g) and measured their tarsus length (±0.1 mm). We also drew a blood sample to determine sex and paternity, as well as hematocrit (see Forsman et al. 2008, 2010; Bowers et al. 2011 for details). We administered a phytohaemagglutinin test in the left wing web (prepatagium) 11 days post-hatching to measure cutaneous immune response. We used a digital thickness gauge (Mitutoyo no. 547–500) to measure pre-injection web thickness three times. We then injected the web intradermally with a 50-μl solution of PHA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; concentration = 5 mg PHA/ml PBS). Upon injection, PHA stimulates recruitment of leucocytes and inflammatory effectors, causing tissue swelling (McCorkle et al. 1980, Martin et al. 2006b, Vinkler et al. 2014). We measured swelling 24 h post-injection. PHA response was the difference between the mean of three pre- and post-injection measures.

To assess abiotic environmental variation, we obtained daily temperature and rainfall data from the National Climatic Data Center for the weather station at Chenoa, McLean County, IL (40°44'N, 88°43'W), the closest (≈16 km) station to the study area. Temperature data at this station are unlikely to have been affected by any heat-island effect from urbanization because the population size of Chenoa was less than 2000 and did not change substantially during the study. Both daily temperature (r645 = 0.319, P < 0.001) and rainfall (r645 = 0.164, P < 0.001) increased over the course of the breeding seasons in which we measured nestling traits, so we included the hatching date of nests as a covariate in our analyses (see below) to account for this and other seasonal environmental variation. For example, the abundance of high-quality arthropod prey, particularly lepidopteran larvae, generally decline over the course of the breeding season in central Illinois forests, and neonates produced later within breeding seasons also have a shorter post-fledging period over which to learn to fly and forage for themselves prior to autumn migration. Thus, the hatching date of nestlings reflects both biotic and abiotic components of environmental variation and likely plays an important role in mediating survival (see also Naef-Daenzer et al. 2001).

Statistics

We used SAS 9.3 for analyses, and tests are two-tailed. Of 3,368 nestlings from 647 broods, 126 (3.7 %) recruited into the breeding population. Among recruits, 86 were captured breeding at one year of age, 21 at two years, 13 at three years, and six at four years of age (those breeding at ages greater than one also bred at younger ages). We included all young banded 11 days post-hatching in all analyses, and analyzed longevity in relation to body mass, tarsus length, PHA responsiveness, hematocrit, and sex using a Cox proportional-hazards regression model (survival analysis; PROC PHREG in SAS). We included hatching date as a covariate to account for environmental variation, and we used the robust sandwich estimator to group offspring within years, their natal nest, and maternal identity to account for non-independence, similar to the use of random effects in linear mixed models (Allison 2010). Because we included tarsus length as a covariate in our analysis, effects of nestling body mass can be interpreted as effects of size-adjusted body mass, or body condition (García-Berthou 2001). This is a useful measure of condition as it frequently predicts lipid reserves slightly better than unadjusted body mass, although the specific index of condition used should generally have no appreciable effect on the outcome of statistical tests (Ardia 2005c, Schamber et al. 2009). The effect of hematocrit on recruitment appeared to be non-linear; thus, we followed our main survival analysis with a logistic regression analyzing the probability of recruitment in relation to hematocrit, including a quadratic term for hematocrit, while controlling for nest of origin, maternal identity, and year. We then analyzed lifetime reproductive success, measured as fledgling production by the neonates in our initial cohorts (see Merilä and Sheldon 2000). We analyzed this using a linear mixed model with the natal nest, maternal identity, and year as random effects and the same predictors used to analyze longevity; we also added quadratic terms to this model (following McGraw and Caswell 1995) because some of the relationships between nestling traits and longevity were non-linear.

Results

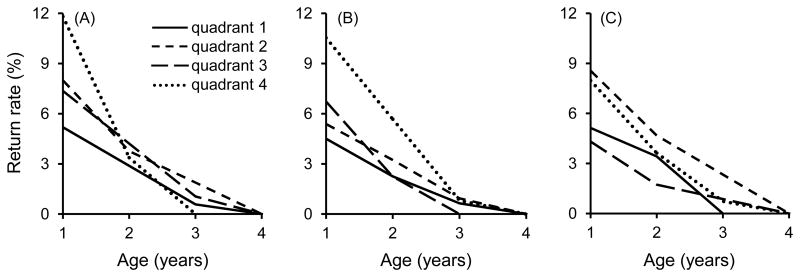

Offspring body condition (size-adjusted mass) and PHA response were each positively correlated with longevity (Table 1). Nestlings with the highest body condition and PHA responsiveness had the highest frequency of breeding at one year of age, and those with the highest PHA responses were most likely to breed through two years of age (Fig. 1, Table 1). Although the probability of breeding as an adult within the population differed slightly between the sexes (mean ± SE: males = 5.2 ± 0.6 %, females = 4.1 ± 0.6 %), there was no sex-difference in the average number of years these individuals bred on the study area (mean ± SE: males = 1.50 ± 0.10 years, females = 1.54 ± 0.13 years).

Table 1.

Relationship between neonatal phenotype and longevity. Negative parameter estimates reflect a positive relationship between the independent variable and age-specific survival.

| Estimate ± SE | Wald χ2 | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass | −0.094 ± 0.040 | 5.72 | 1 | 0.017 |

| Tarsus length | −0.035 ± 0.046 | 0.58 | 1 | 0.445 |

| PHA responsiveness | −0.623 ± 0.108 | 33.21 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Hematocrit | 0.024 ± 0.006 | 18.86 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.102 ± 0.042 | 5.97 | 1 | 0.015 |

| Hatching date | 0.010 ± 0.002 | 30.76 | 1 | < 0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Longevity in relation to (A) neonatal body mass, (B) PHA responsiveness, and (C) hematocrit (product-limit estimates). Data are pooled by quartiles for visualization (quadrant 4 contains the upper 75th percentile).

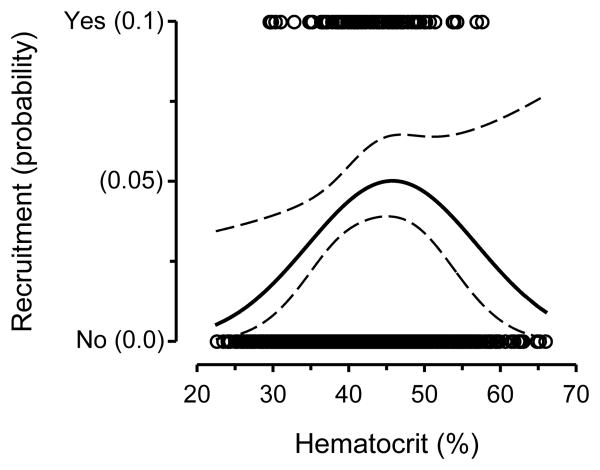

The relationship between hematocrit and longevity was more complex than for body condition and PHA responsiveness. Nestlings with slightly below-average hematocrit had the highest recruitment and were most likely to breed through three years of age (Fig. 1C, Table 1), resulting in an overall negative association between hematocrit and longevity. However, nestlings with the highest hematocrit also tended to have above-average recruitment; thus, we followed up our main survival analysis with a logistic regression to analyze recruitment in relation to hematocrit. This analysis included nestling hematocrit as both a linear (parameter estimate ± SE = 0.402 ± 0.191, χ2 = 7.13, P = 0.008) and a quadratic term (parameter estimate ± SE = −0.004 ± 0.002, χ2 = 6.39, P = 0.012) that confirmed that nestlings with intermediate hematocrit had the highest recruitment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Recruitment into the breeding population in relation to hematocrit. The curve represents the logistic regression line (probability of recruitment) ± 95 % confidence limits.

Responsiveness to PHA injection and hematocrit had similar effects on the reproductive success of neonates as they did on longevity (Table 2). The number of offspring an individual fledged in its lifetime breeding on the study site was positively associated with PHA responsiveness, while intermediate hematocrit predicted the highest future reproductive success.

Table 2.

Relationship between neonatal phenotype and lifetime reproductive success (as assessed by total observed fledgling production).

| Estimate ± SE | F | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass | 0.700 ± 0.878 | 0.63 | 1, 1290 | 0.426 |

| Tarsus length | 0.074 ± 0.094 | 0.62 | 1, 1052 | 0.431 |

| PHA responsiveness | −1.077 ± 0.486 | 4.92 | 1, 640 | 0.027 |

| Hematocrit | 0.142 ± 0.078 | 3.25 | 1, 982 | 0.072 |

| Sex | 0.039 ± 0.104 | 0.14 | 1, 1304 | 0.707 |

| Mass2 | −0.038 ± 0.045 | 0.72 | 1, 1280 | 0.396 |

| PHA2 | 0.905 ± 0.314 | 8.33 | 1, 1085 | 0.004 |

| Hematocrit2 | −0.002 ± 0.001 | 3.29 | 1, 972 | 0.070 |

| Hatching date | −0.005 ± 0.003 | 3.38 | 1, 102 | 0.069 |

| Intercept | −5.984 ± 4.592 |

Discussion

In our study population, cutaneous immune responsiveness to PHA injection was positively correlated with longevity and future reproductive success after controlling for body condition, sex, and environmental variation. Nestlings mounting the highest PHA responses had the highest inter-annual return rates, suggesting that, in an ecological context, optimal responsiveness lies closer to the maximum than usually thought. Indeed, recent studies have found positive associations between PHA responsiveness and recruitment in local populations (Cichoń and Dubiec 2005, Moreno et al. 2005, López-Rull et al. 2011); however, our study is unique in that we were able to follow individuals from multiple cohorts to analyze longevity as a combination of local recruitment and subsequent inter-annual survival within the population, a major determinant of fitness (McCleery et al. 2004, see also Cam et al. 2002). Life-history theory posits that, within and among species, investment in immune function should vary with pace of life (Ricklefs and Wikelski 2002, Lee 2006). Specifically, investment in general and inflammatory immune responses should be favored in short-lived species with rapid growth, short generation times, and high juvenile mortality (i.e., type III survivorship), whereas specific and humoral immune responses should be favored in long-lived species with longer development times and type I survivorship (Mauck et al. 2005, Tieleman et al. 2005, Martin et al. 2007, Lee et al. 2008, Arriero et al. 2013). PHA-induced skin swelling is a very general measure of cutaneous immune responsiveness that encompasses components of both innate and acquired immunity (Martin et al. 2006b), although recent work suggests that this response is primarily innate and that the adaptive component contributes much less to this response than traditionally thought (Vinkler et al. 2014). That most neonates in our study did not recruit to the breeding population, but that those with highest neonatal PHA responsiveness had the highest return rates suggests a critical role for this general, inflammatory response in such a short-lived species.

The production of an immune response to PHA injection is often thought to be energetically costly and potentially traded off against other functions, such as growth or reproduction (Martin et al. 2003, 2006a, Tschirren et al. 2003, Dubiec et al. 2006). Although compelling examples of trade-offs between immunity and other life-history functions have been documented (Ilmonen et al. 2000, Casto et al. 2001, Hanssen et al. 2004, Ardia 2005b, Martin et al. 2008, Knowles et al. 2009), results are frequently mixed and context-dependent (Williams et al. 1999, Lochmiller and Deerenberg 2000, Norris and Evans 2000, Bowers et al. 2012). A recent analysis of a subset of nestlings involved in this study indicates that PHA responsiveness is positively correlated with body mass (Forsman et al. 2010, see also Westneat et al. 2004, Gleeson et al. 2005 for similar examples in other study species), contrary to what might be predicted if growth and immunodevelopment are traded off against each other. Thus, our findings for body condition and immune responsiveness are consistent with the concept of individual quality or the ability to acquire resources as a mediator of life-history trade-offs (van Noordwijk and de Jong 1986, Ardia 2005a, Love et al. 2008, Hamel et al. 2009a,b; Wilson and Nussey 2010, French et al. 2011), contributing to variation in fitness within populations. Although quality is difficult to define and to quantify (Pirsig 1974, Wilson and Nussey 2010), our results suggest potential for this concept as not merely an abstract construct, but as a complex, multivariate phenotype contributing strongly to individual differences in fitness. Indeed, if all individuals optimize life-history trade-offs, differences in longevity and reproductive success within populations should be random and much smaller than what is often observed (e.g., Bérubé et al. 1999; Cam et al. 2002; Hamel et al. 2009a,b), suggesting a role for individual quality in determining differences in survival and reproduction in the wild.

Hematocrit may also have important consequences for individual quality and fitness (Williams 2012). Oxygen-carrying capacity shapes an individual's ability to perform nearly all life-history functions, and low hematocrit is often associated with parasitism and poor nutrition (Richner et al. 1993, Ots et al. 1998, Potti et al. 1999, Kilgas et al. 2006, Fair et al. 2007). Thus, the relationship between hematocrit and longevity that we detected could be paradoxical if hematocrit was always positively indicative of condition, but this is not likely to be the case. High hematocrit can result from dehydration, and, given that hematocrit is positively associated with metabolism (Hammond et al. 2000, Fair et al. 2007), it is also possible that increased neonatal hematocrit reflects heightened metabolic activity, with potential costs to longevity. Increases in hematocrit also cause blood viscosity to increase at an increasing rate (Birchard 1997, Williams 2012). Therefore, oxygen transport is reduced in individuals with both below- and above-optimal hematocrit (Birchard 1997, Schuler et al. 2010, Williams 2012). For example, maximal oxygen uptake in wild-type mice in the laboratory occurred at intermediate hematocrit values, and their exhaustion during exercise came about faster at hematocrit values both below and above the optimal range (Schuler et al. 2010). Although differences in mean hematocrit values may exist among species, the hypothesis of an optimal hematocrit can easily be expanded to predict Darwinian fitness in the wild. Our data suggest that optimal hematocrit for physical activities, such as learning to fly and avoiding predators, lies well below maximal values (Fig. 2). Interestingly, hematocrit often declines in breeding individuals providing energetically demanding parental care relative to non-breeding individuals across a wide range of vertebrate taxa (Williams et al. 2004, Fair et al. 2007, Hanson and Cooke 2009, Cooke et al. 2010), although further work is needed to determine whether this is an adaptive reduction to facilitate increased energetic demands or a consequence of osmoregulatory adjustments to blood during reproduction (Williams et al. 2004, Fair et al. 2007, Wagner et al. 2008, Williams 2012). Thus, hematocrit may play an important role in the life history of all vertebrates, and further experimental work may shed light on the functional significance of this trait in mediating long-term consequences for survival and reproduction.

In conclusion, body condition, cutaneous immune responsiveness, and hematocrit have a pronounced influence on longevity in this wild bird population. These traits may be best regarded, not as proxies or surrogates of fitness (see also Wilson and Nussey 2010 for discussion), but as a subset of traits that contribute to variation in fitness within populations. Future work investigating the genetic variation underlying such traits, paired with experimental studies that manipulate individual differences in phenotypic quality (e.g., body condition, immune responsiveness, or hematocrit), while determining the consequences of such variation, could provide insight into how natural selection acts on these traits in the wild.

Acknowledgments

We thank the 2004-2013 Wren Crews for field assistance and the ParkLands Foundation (Merwin Preserve), the Illinois Great Rivers Conference of the United Methodist Church, and the Sears and Butler families for the use of their properties. Financial support was provided by NSF grants IBN-0316580, IOS-0718140 and IOS-1118160; NIH grant R15HD076308-01; the School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University; and student-research grants from the American Ornithologists' Union, the American Museum of Natural History's Frank M. Chapman Fund, the Sigma Xi Society, the Champaign County Audubon Society, and the Beta Lambda Chapter of the Phi Sigma Biological Sciences Honor Society. All activities complied with the Illinois State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol Nos.17-2003, 15-2006,10-2009, 05-2010, 04-2013) and the United States Geological Survey banding permit 09211.

Literature Cited

- Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using SAS®: A Practical Guide. 2nd. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ardia DR. Individual quality mediates trade-offs between reproductive effort and immune function in tree swallows. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2005a;74:517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Ardia DR. Tree swallows trade off immune function and reproductive effort differently across their range. Ecology. 2005b;86:2040–2046. [Google Scholar]

- Ardia DR. Super size me: an experimental test of the factors affecting lipid content and the ability of residual body mass to predict lipid stores in nestling European starlings. Functional Ecology. 2005c;19:414–420. [Google Scholar]

- Arriero E, Majewska A, Martin TE. Ontogeny of constitutive immunity: maternal vs. endogenous influences. Functional Ecology. 2013;27:472–478. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé CH, Festa-Bianchet M, Jorgenson T. Individual differences, longevity, and reproductive senescence in bighorn ewes. Ecology. 1999;80:2555–2565. [Google Scholar]

- Birchard GF. Optimal hematocrit: theory, regulation and implications. American Zoologist. 1997;37:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Both C, Visser ME, Verboven N. Density-dependent recruitment rates in great tits: the importance of being heavier. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1999;266:465–469. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers EK, Sakaluk SK, Thompson CF. Adaptive sex allocation in relation to hatching synchrony and offspring quality in house wrens. American Naturalist. 2011;177:617–629. doi: 10.1086/659630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers EK, Smith RA, Hodges CJ, Zimmerman LM, Thompson CF, Sakaluk SK. Sex-biased terminal investment in offspring induced by maternal immune challenge in the house wren (Troglodytes aedon) Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2012;279:2891–2898. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers EK, Sakaluk SK, Thompson CF. Sibling cooperation influences the age of nest-leaving in an altricial bird. American Naturalist. 2013;181:775–786. doi: 10.1086/670244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cam E, Link WA, Cooch EG, Monnat JY, Danchin E. Individual covariation in life-history traits: seeing the trees despite the forest. American Naturalist. 2002;159:96–105. doi: 10.1086/324126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casto JM, Nolan V, Jr, Ketterson ED. Steroid hormones and immune function: experimental studies in wild and captive dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis) American Naturalist. 2001;157:408–420. doi: 10.1086/319318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichoń M, Dubiec A. Cell-mediated immunity predicts the probability of local recruitment in nestling blue tits. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2005;18:962–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock TH, Major M, Albon SD, Guinness FE. Early development and population dynamics in red deer. I. Density-dependent effects on juvenile survival. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1987;56:53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke SJ, Schreer JF, Wahl DH, Philipp DP. Cardiovascular performance of six species of field-acclimatized centrarchid sunfish during the parental care period. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2010;213:2332–2342. doi: 10.1242/jeb.030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson RD, Bortolotti GR. Variation in hematocrit and total plasma proteins of nestling American kestrels (Falco sparverius) in the wild. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1997;117A:383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Drilling NE, Thompson CF. Natal and breeding dispersal in house wrens (Troglodytes aedon) Auk. 1988;105:480–491. [Google Scholar]

- Dubiec A, Cichoń M, Deptuch K. Sex-specific development of cell-mediated immunity under experimentally altered rearing conditions in blue tit nestlings. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273:1759–1764. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair J, Whitaker S, Pearson B. Sources of variation in haematocrit in birds. Ibis. 2007;149:535–552. [Google Scholar]

- Forsman AM, Vogel LA, Sakaluk SK, Johnson BG, Masters BS, Johnson LS, Thompson CF. Female house wrens (Troglodytes aedon) increase the size, but not immune responsiveness, of their offspring through extra-pair mating. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:3697–3706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman AM, Sakaluk SK, Thompson CF, Vogel LA. Cutaneous immune activity, but not innate immune responsiveness, covaries with mass and environment in nestling house wrens (Troglodytes aedon) Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 2010;83:512–518. doi: 10.1086/649894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SS, Dearing MD, Demas GE. Leptin as a physiological mediator of energetic trade-offs in ecoimmunology: implications for disease. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2011;51:505–513. doi: 10.1093/icb/icr019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard JM, Festa-Bianchet M, Delorme D, Jorgenson J. Body mass and individual fitness in female ungulates: bigger is not always better. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2000;267:471–477. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Berthou E. On the misuse of residuals in ecology: testing regression residuals vs. the analysis of covariance. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2001;70:708–711. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson DJ, Blows MW, Owens IPF. Genetic covariance between indices of body condition and immunocompetence in a passerine bird. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2005;5:61–69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AL, Hayward AD, Watt KA, Pilkington JG, Pemberton JM, Nussey DH. Fitness correlates of heritable variation in antibody responsiveness in a wild mammal. Science. 2010;330:662–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1194878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AJ. Mass/length residuals: measures of body condition or generators of spurious results? Ecology. 2001;82:1473–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R, Besson AA, Bellenger J, Ragot K, Lizard G, Faivre B, Sorci G. Correlational selection on pro- and anti-inflammatory effectors. Evolution. 2012;66:3615–3623. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel S, Gaillard JM, Festa-Bianchet M, Côté SD. Individual quality, early-life conditions, and reproductive success in contrasted populations of large herbivores. Ecology. 2009a;90:1981–1995. doi: 10.1890/08-0596.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel S, Côté SD, Gaillard JM, Festa-Bianchet M. Individual variation in reproductive costs of reproduction: high-quality females always do better. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2009b;78:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond KA, Chappell MA, Cardullo RA, Lin RS, Johnsen TG. The mechanistic basis of aerobic performance in red junglefowl. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2000;203:2053–2064. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.13.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KC, Cooke SJ. Nutritional condition and physiology of paternal care in two congeneric species of black bass (Micropterus spp.) relative to stage of offspring development. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 2009;179:253–266. doi: 10.1007/s00360-008-0309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen SA, Hasselquist D, Folstad I, Erikstad KE. Costs of immunity: immune responsiveness reduces survival in a vertebrate. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2004;271:925–930. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka W, Smith JNM. Determinants and consequences of nestling condition in song sparrows. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1991;60:995–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Ilmonen P, Taarna T, Hasselquist D. Experimentally activated immune defence in female pied flycatchers results in reduced breeding success. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2000;267:665–670. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LS. House wren (Troglodytes aedon) In: Poole A, editor. The Birds of North America Online. 2nd. Cornell Lab of Ornithology and American Ornithologists' Union; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kilgas P, Tilgar V, Mänd R. Hematological health state indices predict local survival in a small passerine bird, the great tit (Parus major) Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 2006;79:565–572. doi: 10.1086/502817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles SCL, Nakagawa S, Sheldon BC. Elevated reproductive effort increases blood parasitaemia and decreases immune function in birds: a meta-regression approach. Functional Ecology. 2009;23:405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts MM, Adriaensen F, Ardia DR, Artemyev AV, Atiénzar F, Bańbura J, et al. The design of artificial nestboxes for the study of secondary hole-nesting birds: a review of methodological inconsistencies and potential biases. Acta Ornithologica. 2010;45:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA. Linking immune defenses and life history at the levels of the individual and the species. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2006;46:1000–1015. doi: 10.1093/icb/icl049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA, Wikelski M, Robinson WD, Robinson TR, Klasing KC. Constitutive immune defences correlated with life-history variables in tropical birds. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2008;77:356–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindén M, Gustafsson L, Pärt T. Selection on fledging mass in the collared flycatcher and the great tit. Ecology. 73:336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Lindström J. Early development and fitness in birds and mammals. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1999;14:343–348. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochmiller RL, Deerenberg C. Trade-offs in evolutionary immunology: just what is the cost of immunity? Oikos. 2000;88:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- López-Rull I, Celis P, Salaberria C, Puerta M, Gil D. Post-fledging recruitment in relation to nestling plasma testosterone and immune responsiveness in the spotless starling. Functional Ecology. 2011;25:500–508. [Google Scholar]

- Love OP, Salvante KG, Dale J, Williams TD. Sex-specific variability in the immune system across life-history stages. American Naturalist. 2008;172:E99–E112. doi: 10.1086/589521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LB, II, Scheuerlein A, Wikelski M. Immune activity elevates energy expenditure of house sparrows: a link between direct and indirect costs? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2003;270:153–158. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LB, II, Han P, Kwong J, Hau M. Cutaneous immune activity varies with physiological state in female house sparrows (Passer domesticus) Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 2006a;79:775–783. doi: 10.1086/504608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LB, II, Han P, Lewittes J, Kuhlman JR, Klasing KC, Wikelski M. Phytohemagglutinin-induced skin swelling in birds: histological support for a classic immunoecological technique. Functional Ecology. 2006b;20:290–299. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LB, II, Weil ZM, Nelson RJ. Immune defense and reproductive pace of life in Peromyscus mice. Ecology. 2007;88:2516–2528. doi: 10.1890/07-0060.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LB, Weil ZM, Nelson RJ. Seasonal changes in vertebrate immune activity: mediation by physiological trade-offs. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2008;363:321–339. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TE, Møller AP, Merino S, Clobert J. Does clutch size evolve in response to parasites and immunocompetence? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:2071–2076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck RA, Matson KD, Philipsborn J, Ricklefs RE. Increase in the constitutive innate humoral immune system in Leach's Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) chicks is negatively correlated with growth rate. Functional Ecology. 2005;19:1001–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell MH, Robertson GW, McCorquodale CC. Whole blood and plasma viscosity values in normal and ascitic broiler chickens. British Poultry Science. 1992;33:871–877. doi: 10.1080/00071669208417528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleery RH, Pettifor RA, Armbruster P, Meyer K, Sheldon BC, Perrins CM. Components of variance underlying fitness in a natural population of the great tit Parus major. American Naturalist. 2004;164:E62–E72. doi: 10.1086/422660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle F, Olah I, Glick B. Morphology of the phytohaemagglutinin-induced cell response in the chicken's wattle. Poultry Science. 1980;59:616–623. doi: 10.3382/ps.0592151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw JB, Caswell H. Estimation of individual fitness from life-history data. American Naturalist. 1995;147:47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Merilä J, Sheldon BC. Lifetime reproductive success and heritability in nature. American Naturalist. 2000;155:301–310. doi: 10.1086/303330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merilä J, Kruuk LEB, Sheldon BC. Natural selection on the genetical component of variance in body condition in a wild bird population. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2001;14:918–929. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GW, Guglielmo CG, Wheelwright NT, Freeman-Gallant CR, Norris DR. Early life events carry over to influence pre-migratory condition in a free-living songbird. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller AP, Saino N. Immune response and survival. Oikos. 2004;104:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J, Merino S, Sanz JJ, Arriero E, Morales J, Tomás G. Nestling cell-mediated immune response, body mass and hatching date as predictors of local recruitment in the pied flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca. Journal of Avian Biology. 2005;36:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Naef-Daenzer B, Widmer F, Nuber M. Differential post-fledging survival of great and coal tits in relation to their condition and fledging date. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2001;70:730–738. [Google Scholar]

- Norris K, Evans MR. Ecological immunology: life-history trade-offs and immune defense in birds. Behavioral Ecology. 2000;11:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Norte AC, Ramos JA, Araújo PM, Sousa JP, Sheldon BC. Health-state variables and enzymatic biomarkers as survival predictors in nestling great tits (Parus major): effects of environmental conditions. Auk. 2008;125:943–952. [Google Scholar]

- Nussey DH, Watt KA, Clark A, Pilkington JG, Pemberton JM, Graham AL, McNeilly TN. Multivariate immune defences and fitness in the wild: complex but ecologically important associations among plasma antibodies, health and survival. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2014;281:20132931. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ots I, Murumägi A, Hõrak P. Haematological health state indices of reproducing great tits: methodology and sources of natural variation. Functional Ecology. 1998;12:700–707. [Google Scholar]

- Packard GC, Boardman TJ. The misuse of ratios, indices, and percentages in ecophysiological research. Physiological Zoology. 1988;61:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pirsig RM. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Bantam Books; New York, NY, USA: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Potti J, Moreno J, Merino S, Frías O, Rodríguez R. Environmental and genetic variation in the haematocrit of fledgling pied flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca. Oecologia. 1999;120:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s004420050826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richner H, Oppliger A, Christe P. Effect of an ectoparasite on reproduction in great tits. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1993;62:703–710. [Google Scholar]

- Ricklefs RE, Wikelski M. The physiology/life-history nexus. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2002;17:462–468. [Google Scholar]

- Sadd BM, Siva-Jothy MT. Self-harm caused by an insect's innate immunity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273:2571–2574. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schamber JL, Esler D, Flint PL. Evaluating the validity of using unverified indices of body condition. Journal of Avian Biology. 2009;40:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler B, Arras M, Keller S, Rettich A, Lundby C, Vogel J, Gassmann M. Optimal hematocrit for maximal exercise performance in acute and chronic erythropoietin-treated mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2010;107:419–423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912924107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Hostedde AI, Zinner B, Millar JS, Hickling GJ. Restitution of mass-size residuals: validating body condition indices. Ecology. 2005;86:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon BC, Verhulst S. Ecological immunology: costly parasite defenses and trade-offs in evolutionary ecology. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1996;11:317–321. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarwater CE, Ricklefs RE, Maddox JD, Brawn JD. Pre-reproductive survival in a tropical bird and its implications for avian life histories. Ecology. 2011;92:1271–1281. doi: 10.1890/10-1386.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tella JL, Scheuerlein A, Ricklefs RE. Is cell-mediated immunity related to the evolution of life-history strategies in birds? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2002;269:1059–1066. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CF, Flux JEC, Tetzlaff VT. The heaviest nestlings are not necessarily the fattest nestlings. Journal of Field Ornithology. 1993;64:426–432. [Google Scholar]

- Tieleman IB, Williams JB, Ricklefs RE, Klasing KC. Constitutive innate immunity is a component of the pace-of-life syndrome in tropical birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2005;272:1715–1720. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinbergen JM, Boerlijst MC. Nestling weight and survival in individual great tits (Parus major) Journal of Animal Ecology. 1990;59:1113–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Tschirren B, Fitze PS, Richner H. Sexual dimorphism in susceptibility to parasites and cell-mediated immunity in great tit nestlings. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2003;72:839–845. [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk AJ, de Jong G. Acquisition and allocation of resources: their influence on variation in life history tactics. American Naturalist. 1986;128:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Viney ME, Riley EM, Buchanan KL. Optimal immune responses: immunocompetence revisited. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2005;20:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkler M, Svobodová J, Gabrielová B, Bainová H, Bryjová A. Cytokine expression in phytohaemagglutinin-induced skin inflammation in a galliform bird. Journal of Avian Biology. 2014;45:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EC, Stables CA, Williams TD. Hematological changes associated with egg production: direct evidence for changes in erythropoiesis but a lack of resource dependence? Journal of Experimental Biology. 2008;211:2960–2968. doi: 10.1242/jeb.017897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westneat DF, Weiskittle J, Edenfield R, Kinnard TB, Poston JP. Correlates of cell-mediated immunity in nestling house sparrows. Oecologia. 2004;141:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1653-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxen TE, Boughton RK, Schoech SJ. Selection on innate immunity and body condition in Florida scrub-jays throughout an epidemic. Biology Letters. 2010;6:552–554. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TD, Challenger WO, Christians JK, Evanson M, Love O, Vezina F. What causes the decrease in haematocrit during egg production? Functional Ecology. 2004;18:330–336. [Google Scholar]

- Williams TD, Christians JK, Aiken JJ, Evanson M. Enhanced immune function does not depress reproductive output. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1999;266:753–757. [Google Scholar]

- Williams TD. Physiological adaptations for breeding in birds. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AJ, Nussey DH. What is individual quality? An evolutionary perspective. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2010;25:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young BE. An experimental analysis of small clutch size in tropical house wrens. Ecology. 1996;77:472–488. [Google Scholar]