Abstract

Historically, type 2 diabetes (T2D) was considered a metabolic disease of aging. However, recent discoveries have demonstrated the role of chronic systemic inflammation in the development of insulin resistance and subsequent progression to T2D. Over the years, investigations into the pathophysiology of T2D have identified the presence of islet specific T cells and islet autoimmune disease in T2D patients. Moreover, the cell-mediated islet autoimmunity has also been correlated with the progressive loss of β-cell function associated with T2D disease pathogenesis. In this manuscript, the involvement of cell-mediated islet autoimmune disease in the progression of T2D disease and the similarities in islet specific T cell reactivity between Type 1 (T1D) and T2D are discussed.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, islet reactive T cells, autoimmunity, T cells, Type 1 diabetes, autoimmune disease, inflammation

Islet-Specific T Cell Responses in Type 1 (T1D) and Type 2 (T2D) Diabetes

Diabetes Mellitus is a disease associated with a continuous spectrum of symptoms and etiologies ranging from a cell-mediated autoimmune disease (T1D) to a non-autoimmune metabolic disorder namely, T2D [1,2]. The cell-mediated autoimmune pathology associated with T1D has been recognized for many years, however the immune cells involved in the β-cell destruction in humans and their β-cell targets have not yet been definitively identified. In 1996, a T cell assay, cellular immunoblotting, was established for investigating islet reactive T cells in subjects with T1D [3]. Using cellular immunoblotting, T cells from T1D patients, at the time of clinical onset, were observed to respond to a multitude of islet proteins [3]. The islet reactive T cell responses in newly diagnosed T1D patients mirrored the islet autoantibody responses in T1D patients with reactivity to numerous islet proteins at onset of clinical diagnosis [4]. Upon further investigation into the islet reactive T cell responses in subjects at high risk for T1D, besides having positivity for multiple islet autoantibodies, these subjects were observed to develop islet reactive T cell responses to increasing numbers of islet proteins prior to onset of clinical diabetes [5]. Cellular immunoblotting was subsequently evaluated and validated in multiple distinct validation trials, along with other T cell assays, and demonstrated to have excellent sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing T1D patients from controls [6,7]. Cellular immunoblotting has also been utilized to demonstrate immune recognition dominance of a number of islet proteins for T cell responses from T1D patients suggesting that some proteins may be more important as initial targets whereas other proteins may be recognized resulting from the β-cell destruction [8].

Changing Ideas on T2D Pathogenesis

Historically, T2D has been considered primarily a metabolic disease of older individuals without involvement of the immune system. Recently, however, cellular inflammation in the pancreatic islets of T2D patients has been identified, and this cellular inflammation may lead some phenotypic T2D patients to develop islet autoreactive T cells and subsequent islet autoimmune disease [9–21]. Islet autoimmunity in T2D patients was initially identified by the presence of islet autoantibodies in various subgroups of T2D patients. These islet autoantibody positive T2D patents experience early sulfonylurea failure and a more rapid decline in endogenous insulin secretion compared to islet autoantibody negative T2D patients [22–24]. The identification of islet reactive T cells in T2D patients is a more recent discovery and the presence of the islet reactive T cells has been associated with more severe β-cell dysfunction compared to islet autoantibody positivity in T2D patients [25,26].

Most studies investigating islet autoimmunity are based on islet autoantibody positivity. Using islet autoantibodies as a biomarker for islet autoimmunity for T2D, the prevalence of islet autoimmunity has been estimated to be between 5–30% [24,27,28]. If β-cells are destroyed in an autoimmune process in T2D patients similar to T1D, the primary effector of β-cell damage would be islet reactive T cells and not islet autoantibodies. If the islet autoimmunity in T2D is cell-mediated, then the percentage of T2D patients with islet autoimmunity, detected by islet autoantibodies alone, may not identify all autoimmune patients. Therefore, the percentage of T2D patients that have islet autoimmunity may be higher than the upper estimated limit of 30%.

Over the years, using cellular immunoblotting, islet reactive T cells have been identified in both adult and pediatric T2D patients [25,26,29,30]. Furthermore, a T2D patient population who are positive for islet reactive T cells but islet autoantibody negative, have also been identified [30]. The autoantibody negative autoimmune T2D patients are reflective of a similar population of autoimmune T1D patients previously identified [31]. These islet autoantibody negative T1D patients, described by Wang et al., were also positive for T1D associated high-risk alleles. The prevalence of these autoantibody negative T1D patients was estimated to comprise up to 19% of newly diagnosed T1D patients [31]. In contrast to Wang’s study, the subset of autoimmune T2D patients identified as autoimmune, with the presence of islet reactive T cells but negative for islet autoantibodies, comprised approximately 50% of the autoimmune T2D patients [30,32].

Islet Autoantibodies versus Islet-reactive T Cells as Biomarkers

Islet autoantibodies have been the primary biological marker for identifying subjects at risk for development of T1D and autoimmune T2D patients even though islet reactive T cells are believed to be the primary effectors in β-cell destruction. When islet autoantibodies and islet reactive T cells in T2D patients were evaluated to determine which would be the better biomarker for identifying β-cell dysfunction in T2D patients, T cell reactivity to islet proteins was observed to be superior to islet autoantibodies as biomarkers for identifying T2D patients with more severe β-cell dysfunction [25]. Future studies may benefit from including assays aimed at detecting islet specific T cell reactivity.

Is Islet Autoimmunity Similar in T1D and T2D?

If islet autoimmune disease is present in both T1D and T2D, is the islet autoimmune disease similar in these two subtypes of autoimmune diabetes? Palmer et al. [33] addressed this question using cellular immunublotting to investigate the T cell reactivity to islet proteins in T1D and T2D patients. These investigators observed that some islet proteins appeared to be similarly recognized by T cells from both T1D and T2D patients and other proteins are recognized differentially by T cells from T1D or T2D patients [33]. At this time, the identities of the T cell stimulatory proteins or T effector cells important in the pathogenesis of human T1D and T2D are unknown. The differences in islet reactive T cell responses between T1D and T2D may reflect basic differences in the autoimmune pathologies between T1D and adult T2D, or the differences may reflect immunological differences in T cell reactivities between youth and adult subjects. The answers to these questions are also awaiting future studies.

Clinical Relevance of Islet-specific T Cell Responses in T2D?

How does the presence of islet specific T cells correlate with β-cell function in T2D pathophysiology? Previous studies have demonstrated that islet reactive T cells appeared to be associated with the progressive loss of β-cell function in T2D patients [25,30,32]. To investigate the interaction of islet specific T cells and β-cell function, autoimmune T2D patients (positive for islet reactive T cells) were randomized onto a diabetes drug known to have anti-inflammatory properties, rosiglitazone, versus a diabetes drug known to stimulate β-cells but without immunoregulatory properties, glyburide in a study conducted by Brooks-Worrell et al. [34]. Attenuation of islet reactive T cell responses by rosiglitazone was significantly associated with improved β-cell function of the T2D patients. Moreover, a significant decrease in IL-12 and INF-γ, pro-inflammatory cytokines, in rosiglitazone treated autoimmune T2D patients compared to the T2D patients treated with glyburide was also observed. Furthermore, a significant increase in adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory adipokine, was also observed in the serum of rosiglitazone treated patients [34].

Summary and Conclusions

In summary, islet reactive T cells have been demonstrated to be important in the pathogenesis of islet autoimmune disease and progressive loss of β-cell function in both adult and pediatric T1D and T2D patients. It is currently not known what the prevalence of islet autoimmunity in T2D patients is. However, studies have indicated that the percentage may be as high as 50% of T2D patients [32]. The development of islet reactive T cells in T2D patients may be related to the established systemic inflammation associated with obesity [20]. If so, how does obesity-associated inflammation contribute to islet autoimmune disease? Is islet autoimmune disease different in T1D versus T2D? Does the cell-mediated islet cell destruction have the same autoimmune foundation in T2D as T1D or is it different? Are the T effector cells the same in both T1 and T2D? Are the islet antigen targets the same in T1D and T2D? Answers to these important questions are awaiting further research.

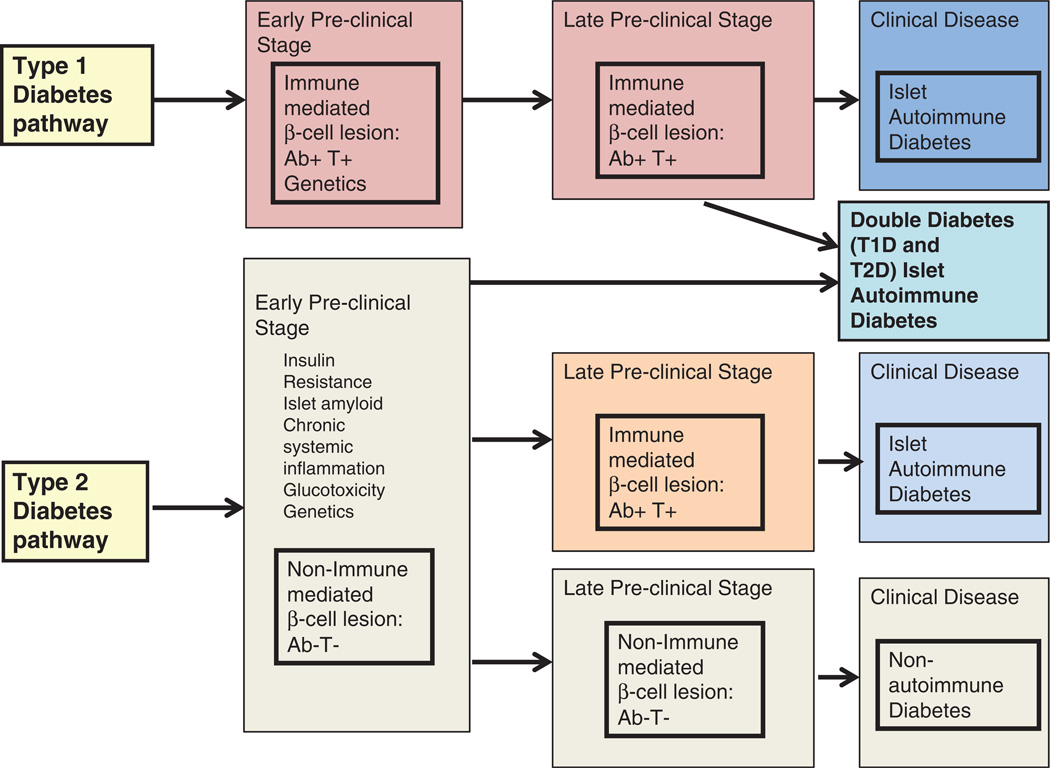

Figure 1 illustrates a potential scenario connecting both T1D and T2D to development of islet autoimmunity. T1D and T2D are not as distinct as once believed, and diabetes mellitus appears to consist of autoimmune and non-autoimmune syndromes in both adults and children. Thus, a more appropriate distinction may be to identify diabetes patients as either autoimmune or non-autoimmune. Stratifying diabetes patients based on autoimmune status would likely identify patients who would receive the most benefit from immunomodulating agents targeted at arresting further β-cell autoimmune destruction.

Figure 1.

Pathways of type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) development. The initial β-cell lesion in T1D is believed to result from islet autoimmune destruction. In contrast, the initial β-cell lesion in T2D is believed to result as a non-autoimmune lesion. The initiating factor in T1D is unknown, whereas the islet autoimmune development in T2D is believed to result from chronic systemic inflammation associated with obesity. In both pathways, inflammatory and effector immune cells reactive to islet proteins result and islet autoimmune destruction occurs. Chronic inflammation, insulin resistance along with β-cell defects/stress/impairment and amyloid are believed to be associated with T2D pathogenesis. It is unknown which of these factors, if any, also are associated with T1D pathogenesis. The resulting islet autoimmune diseases bridge the two forms of diabetes into one encompassing autoimmune phenomenon. “Double Diabetes” results from both T1D and T2D.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING STATEMENT:

The grants that supported the research described in the manuscript are the following:

NIH 1RO1DK083471

NIH P30DK017047

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

None of the authors report any conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Brooks-Worrell B, Palmer JP. Is diabetes mellitus a continuous spectrum? Clin Chem. 2011;57:158–161. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.148270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merger SR, Leslie RD, Boehm BO. The broad clinical phenotype of type 1 diabetes at presentation. Diabet Med. 2013;30:170–178. doi: 10.1111/dme.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks-Worrell BM, Starkebaum GA, Greenbaum C, Palmer JP. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells of insulin-dependent diabetic patients: respond to multiple islet cell proteins. J Immunol. 1996;157:5668–5674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nokoff N, Rewers M. Pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes: lessons from natural history studies of high-risk individuals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1281:1–15. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks-Worrell B, Gersuk VH, Greenbaum C, Palmer JPP. Intermolecular antigen spreading occurs during the preclinical period of human type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2001;166:5265–5270. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seyfert-Margolis V, Gisler TD, Asare AL, et al. Analysis of T-cell assays to measure autoimmune responses in subjects with type 1 diabetes: results of a blinded controlled study. Diabetes. 2006;55:2588–2594. doi: 10.2337/db05-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herold KC, Brooks-Worrell B, Palmer JP, et al. Validity and reproducibility of measurement of islet autoreactivity by T cell assays in subjects with early type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:2588–2595. doi: 10.2337/db09-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks-Worrell B, Warsen A, Palmer JP. Improved T cell assay for identification of type 1 diabetes patients. J Immunol Method. 2009;344:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:98–107. doi: 10.1038/nri2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehses JA, Ellingsgaard H, Boni-Schnetzler M, Donath MY. Pancreatic islet inflammation in type 2 diabetes: from α and β cell compensation to dysfunction. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2009;115:240–247. doi: 10.1080/13813450903025879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donath MY, Schumann DM, Faulenbach M, Ellingsgaard H, Perren A, Ehses JA. Islet inflammation in type 2 diabetes: from metabolic stress to therapy. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S161–S164. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donath MY, Boni-Schnetzler M, Ellingsgaard H, Ehses JA. Islet inflammation impairs the pancreatic β-cell in type 2 diabetes. Physiology. 2009;4:325–331. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spranger J, Kroke A, Mohlig M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: results of the prospective population-based European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)-potsdam study. Diabetes. 2003;52:812–817. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalupahana NS, Moustaid-Moussa N, Claycomb KJ. Immunity as a link between obesity and insulin resistance. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolb H, Mandrup-Poulsen T. An immune origin of type 2 diabetes? Diabetologia. 2005;48:1038–1050. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1764-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Festa A, D'Agostino RR, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Elevated levels of acute-phase proteins and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 predict development of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes. 2002;51:1131–1137. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1793–1801. doi: 10.1172/JCI29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pradhan DA, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks-Worrell B, Palmer JP. Clinical immunology review series: Focus on metabolic diseases: Development of islet autoimmune disease in type 2 diabetes patients: potential sequelae of chronic inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fourlanos S, Dotta F, Greenbaum CJ, et al. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) should be less latent. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2206–2212. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner R, Stratton I, Horton V, et al. UKPDS 25: autoantibodies in islet-cell cytoplasm and glutamic acid decarboxylase for prediction of insulin requirement in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 1997;350:1288–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)03062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuomi T, Groop L, Zimmet P, et al. Antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase reveal latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults with a non-insulin-dependent onset of disease. Diabetes. 1992;42:359–362. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmet P, Tuomi T, Mackay I, et al. Latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus in adults (LADA): The role of antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase in diagnosis and prediction of insulin dependency. Diabet Med. 1994;11:299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goel A, Chiu H, Felton J, Palmer JP, Brooks-Worrell B. T cell responses to islet antigens improves detection of autoimmune diabetes and identifies patients with more severe β-cell lesions in phenotypic type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2110–2115. doi: 10.2337/db06-0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks-Worrell BM, Juneja R, Minokadeh A, Greenbaum CJ, Palmer JP. Cellular immune response to human islet proteins in antibody-positive type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1999;48:983–988. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groop L, Botazzo GF, Koniach D. Islet cell antibodies identify latent type 1 diabetes in patients aged 35–75 years at diagnosis. Diabetes. 1986;35:237–241. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juneja R, Hirsch IB, Naik RG, Brooks-Worrell BM, Greenbaum CJ, Palmer JP. Islet cell antibodies and glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies but not the clinical phenotype help to identify type 1 1/2 diabetes in patients presenting with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2001;50:1008–1013. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.25654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks-Worrell BM, Greenbaum CJ, Palmer JP, Pihoker C. Autoimmunity to islet proteins in children diagnosed with new-onset diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2222–2227. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks-Worrell BM, Reichow JL, Goel A, Ismail H, Palmer JP. Identification of autoantibody-negative autoimmune type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:168–173. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Miao D, Babu S, et al. Prevalence of autoantibody-negative diabetes is not rare at all ages and increases with older age and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:88–92. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks-Worrell B, Ismail H, Wotring M, Kimmie C, Felton J, Palmer JP. Autoimmune development in phenotypic type 2 diabetes patients. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:S66–S67. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer JP, Hampe CS, Chiu H, Goel A, Brooks-Worrell BM. Is latent autoimmune diabetes in adults distinct from type 1 diabetes or just type 1 diabetes at an older age? Diabetes. 2005;54:S62–S67. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks-Worrell, Palmer JP. Attenuation of islet-specific T cell responses is associated with C-peptide improvement in autoimmune type 2 diabetes patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;171:164–170. doi: 10.1111/cei.12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]