Abstract

Crohn’s disease is a chronic disorder characterized by episodes of epithelial inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract for which there is no cure. The prevalence of Crohn’s disease increased in civilized nations during the time period in which food sources were industrialized in those nations. A characteristic of industrialized diets is the conspicuous absence of cereal fiber. The purpose of this two-group, randomized, controlled study was to investigate the effects of fiber-related dietary instructions specifying wheat bran consumption on health-related quality of life and gastrointestinal function in individuals diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, as measured by the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire and the partial Harvey Bradshaw Index, respectively. Results demonstrated that consuming a wheat bran inclusive diet was feasible and caused no adverse effects, and participants consuming whole wheat bran in the diet reported improved health-related quality of life (p = 0.028) and gastrointestinal function (p = 0.008) compared to the attention control group. The results of a secondary aim, to investigate differences in measures of systemic inflammation, found no group differences in C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rates. This study suggests that diet modification may be a welcomed complementary therapy for individuals suffering gastrointestinal disruption associated with CD.

Background

Genetic and environmental factors jointly contribute to expression of Crohn’s disease (CD). Genome-wide association studies have identified genetic risk factors for phenotypic-specific CD behaviors (Barrett et al., 2008; Lichtenstein et al., 2011). However, epidemiologic studies of CD expression point to a strong environmental component and may offer clues to alternative variables that could be targeted in CD management plans (Bernstein, 2010). For example, children of immigrants to industrialized nations have a higher incidence of CD, exhibiting a rate of risk associated with the host nation versus the risk associated with the nation of origin (Pinsk et al., 2007). Thus, the interplay between an individual’s genetic composition and the effect of poorly understood environmental influences add complexity to the task of controlling symptoms of CD in a given individual.

Despite advances in pharmacologic and surgical interventions for CD, many individuals continue to experience lingering symptoms, often including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and intestinal bleeding (Lichtenstein, Hanauer, & Sandborn, 2009). A survey conducted at the Cleveland Clinic indicated that symptoms affected the work of 68% of respondants with CD, and 28 % of individuals with CD found it necessary to change jobs because of symptoms (Zutshi, Hull, & Hummel, 2007). The annual CD-treatment cost is estimated to be $3.6 billion annually (Kappelman, Palmer, Boyle, & Rubin, 2010).

Burkitt (1984) hypothesized that the systematic removal of cereal fiber from industrialized foods was a factor that might account for the observed increase in CD incidence in Western nations. Over time, steel roller milling of cereal grains replaced stonegrinding; consequently, the food products made from wheat flour became devoid of the fibrous bran layer in the diets of civilized populations (Hill, 1976). During the last decades of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, intentional replacement of wheat bran in the diet through the consumption of whole wheat bran cereal by individuals diagnosed with CD has not been studied systematically; however, observations of patients who consume whole wheat bran cereal indicate long-term remission in symptoms (Brotherton, Taylor, & Herman, 2012; Brotherton & Taylor, 2012). Wheat bran is a naturally complete cereal fiber, and questions raised by Burkitt’s cereal fiber hypothesis of chronic disease (1984) remain unanswered and constitute the basis for additional investigation. In this article, the word “whole” preceeds the term “wheat bran” to emphasize the relative completeness of wheat bran in contrast to fiber additives based on fractionated fiber extracts that are used in the food industry to boost the fiber content of processed foods.

The rationale for the consumption of whole wheat bran cereal for the symptoms of CD includes beneficial microscopic effects in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Specifically, these microscopic effects include the actions of butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids, which are metabolites of bacterial fermentation of complex carbohydrates (Benjamin et al., 2011; Kalha & Sellin, 2004; Pryde, Duncan, Hold, Stewart, & Flint, 2002). Butyrate participates in restitution of colonic epithelium following tissue breakdown, stimulates the normal phenotypic expression of epithelial cells and provides on-going sustenance of these cells, regulates tight junction permeability between adjacent cells, and down-regulates nuclear factor kappa beta, leading to decreased tumor necrosis factor and theoretically reducing the risk of chronic inflammation (Kripke, Fox, Berman, Settle, & Rombeau, 1989; Ohata, Usami, & Miyoshi, 2005; Segain et al., 2000; Sturm & Dignass, 2008; Topping & Clifton, 2001). In short, wheat bran is a fermentable carbohydrate capable of playing a role in the function of human intestines by providing available substrate to beneficial strains of microbiota in the gut, which, in turn, contribute to proper laxation and biochemical functionality (Macfarlane & Macfarlane, 2011).

The rationale for the consumption of whole wheat bran cereal for the symptoms of CD aslo includes beneficial macroscopic effects in the GI tract. For example, macroscopic effects include high water-holding capacity that helps balance the ratio of unbound water to the water-holding capacity of luminal contents, slowing intestinal transit time for improved control of diarrhea (Fine & Schiller, 1999). It is also known that in the case of excessively long intestinal transit time (constipation), the added bulk and stool weight provided by wheat bran increases the speed at which stool moves, correcting constipation. Thus, dietary fiber assists in correcting both diarrhea and constipation. Understanding the benefits of dietary fiber consumption is not only relevant to patients with CD in times of exacerbation. This understanding is also relevant during times of remission, when a low fiber diet can lead to subclinical constipation that would increase antigen/epithelial exposure time and possibly increase the risk of initiating an inflammatory response.

Whereas CD treatment during a period of exacerbation targets induction of remission, CD treatment during a period of remission is aimed at avoiding future flares. It is logical that prevention of constipation is beneficial, because the abnormally long transit time associated with constipation increases the contact time between antigens in the stool and epithelial surfaces. Normalizing transit time, or absence of constipation, decreases exposure time, decreasing the potential for initiation of an immune response. It is also logical that the added bulk provided by dietary fiber dilutes the concentration of antigens present in the stool, further decreasing the potential for initiation or perpetuation of an immune response. The combined macroscopic and microscopic effects of complex, fermentable carbohydrates provide the rationale for testing the effects of wheat bran and other fibers on health-related quality of life (HQoL) and GI function in samples of individuals diagnosed with CD (Yamamoto, Nakahigashi, & Saniabadi, 2009).

Previous fiber-related CD studies have produced inconclusive and conflicting results, providing no evidence to support recommendations regarding dietary fiber intake (Benjamin et al., 2011; Chapman-Kiddell, Davies, Gillen, & Radford-Smith, 2010). However, some previous studies investigated the heterogenous group of substances known as total dietary fiber and may have failed to tease out the types of fiber most relevant to GI health. Other previous studies tested fractionated fiber extracts, or food additives. Researchers did not test wheat bran, which is a more complete dietary fiber and the specific fiber conspicuously absent in the diet of Americans who habitually consume refined flour food products. Additionally, previous study protocols investigating fiber extracts did not test a comprehensive change to a dietary pattern emphasizing foods containing whole fiber.

A recent example of the second type of study was conducted by Benjamin et al. (2011). Fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS), a fermentable carbohydrate available in powder form, was tested in a sample of individuals with active CD symptoms, without any other dietary modifications. FOS, a powder that participants stirred into a drink twice daily, was found to increase GI symptoms and the dropout rate in the active intervention group was high (26%). Having concluded that fermentable carbohydrates may increase functional symptoms associated with CD, the authors recommended that future studies investigating fermentable carbohydrates should not focus on individuals with active symptoms. However, this sweeping recommendation is an unsupported generalization of findings from an investigation of a single fractionated fiber to all future studies investigating fermentable carbohydrates. This generalization does not account for the heterogeneity of dietary fibers, the potential differences in physiologic effects associated with different dietary fiber types, and the possibility that a different dietary fiber may produce more favorable results.

Study Purpose and Aims

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of fiber-related dietary instructions specifying daily consumption of whole wheat bran cereal and restriction of refined carbohydrates on HQoL and GI function in individuals diagnosed with CD. Three primary aims and one secondary aim guided the current project. Primary Aim 1 was to determine the feasibility of the trial, including patient acceptance, potential limitations of the protocol, and the rate of patient accrual over time using the proposed sampling criteria, as well as the percentage of eligible participants who chose to participate, participant attrition over time, and reasons for attrition. Primary Aim 2 was to determine the effects of dietary instructions to consume whole wheat bran cereal and restrict refined carbohydrates compared to general dietary instruction on HQoL in persons with CD as measured by the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ). Primary Aim 3 was to determine the effects of dietary instructions to consume whole wheat bran cereal and restrict refined carbohydrates compared to general dietary instruction on GI function in persons with CD as measured by the partial Harvey Bradshaw Index (pHBI). We hypothesized that individuals who were provided dietary fiber information and instructed to consume a well-defined high fiber diet including whole wheat bran consumption would have improved HQoL and GI function during a 4-week study period compared to a similar group of individuals who were given more general dietary information and instructed to concentrate on identification of potential trigger foods in the diet as is commonly suggested to individuals with CD (CCFA, Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, 2011). A secondary aim was to determine the effect of dietary instructions (to consume wheat bran cereal and restrict refined carbohydrates compared to general dietary instructions) on biomarkers of inflammation, C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Methods

Design

A two-group, randomized, controlled, single-blind, 4-week trial design was chosen to test the effects of one-on-one, face-to-face delivery of dietary fiber information and specific instructions (verbal and written as a take-home sheet) to consume a high fiber and low refined carbohydrate diet including consumption of whole wheat bran cereal. The 4-week duration was chosen for this investigation based on informal observations of the effects of this dietary pattern in individuals with CD, not on formal published CD literature. Each enrolled participant was randomized to receive either the dietery fiber instruction or the control diet instruction; however, participants were not informed that there were two groups because the researchers sought to reduce the chance of differing expectations of improvement between groups at baseline. If the two groups had differed in expectation of improvement during the study, such a difference could have been a confounding variable in the outcomes analyses. Both groups (intervention and attention-control) completed the same baseline forms and study questionnaires, received a presentation of dietary information, provided a baseline blood sample, kept a daily diary, received weekly telephone calls from the study coordinator, completed weekly and biweekly study measures, and returned for an end-of-study visit at week 4. At the final visit, all participants provided a second blood sample, submitted final study questionnaires, and were debriefed regarding the 2-group design of the study. At the conclusion of this appointment, each participant was offered the opportunity to decline inclusion of his or her study data in the analysis after learning that the study used a 2-group design, of which they were not informed at the start of the study.

Sample

Individuals diagnosed with CD through colonoscopy and biopsy and who were aged 18 to 64 years were recruited. Requirements included a pHBI score ≥3 and at least 4 weeks of stable pharmacologic therapy. Excluded from the study were individuals with short bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, or any other major diagnosis that affects the GI tract; special dietary restrictions; mental, emotional, cognitive, or other disorders that might interfere with the ability to independently follow detailed dietary instructions over time; cancer; pregnancy; unstable or uncontrolled kidney or cardiovascular disease; decompensated liver disease; penetrating CD; clinically significant stricturing CD; and a pHBI score >9. To reduce confounding of study results that would have been associated with variations in dosing schedules for biologic therapy, individuals using biologic drugs (adalimumab, cerolizumab pegol, infliximab, and natalizumab) were also excluded from the study.

Power Analysis

Using results based on the IBDQ scores from the budesonide study by Irvine et al. (Irvine et al., 2000), the targeted sample size for this study was 22 participants in each group to achieve 80% power with α= 0.05, a mean difference, and SD of 27.4 ± 30 (range of 22–32). Despite the fact that the budesonide study tested a pharmacological agent versus a diet intervention, the study was chosen to inform the proposed sample size for the current study because the budesonide investigators used the IBDQ and reported sufficient information in the literature to be usable. No report of a dietary study using the IBDQ was found in the literature.

Procedures

After approval by the University of Virginia Health Sciences Research Institutional Review Board, potential participants were informed of the study either during a regular inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinic visit, through an approved recruitment letter sent to 10 potential participants identified in a chart review, or through a publicly posted recruitment flyer. Interested individuals were further informed about the study through a telephone conversation with the study coordinator and then scheduled for a study visit to review the protocol and consent form. After signing the consent, all participants completed demographic and health history forms described below. Individuals under the care of the study physician also completed baseline measures, received the dietary fiber information and intervention instructions, and had a baseline blood sample drawn at this initial appointment. Individuals not under the care of the study physician signed a form giving approval to the study cordinator to contact his/her gastroenterologist for confirmation of diagnosis via fax. These participants scheduled a later baseline appointment for completion of baseline protocol activities. Participants received $50 cash at the conclusion of the baseline appointment to defray the cost of purchasing any new foods needed to follow the dietary instructions. Participants in the active intervention group also were given a full set of 28 daily servings of a commercially available whole wheat bran cereal for use during the study. The cereal provided to the participants was purchased at retail prices from a local grocery store. At week 4, all participants returned for a final debriefing appointment when a second blood sample was drawn and they were each given $150 for completing the study.

Measures

All participants completed weekly and bi-weekly study questionnaires and participated in a weekly telephone interview at which time the study coordinator asked questions needed to score the pHBI for the week and addressed any study-related issues raised by the participant. Measures and assessment times are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measures and assessment times

| Visit 1 Screening | Visit 2 Baseline | At-home Assessments

|

Visit 3 Wk 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wk 1 | Wk 2 | Wk 3 | ||||

| Informed Consent | X | |||||

| Demographics | X | |||||

| Health History | X | X | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Health-Related Quality of Life | ||||||

| •Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) | X | X | X | |||

|

| ||||||

| Intestinal Function completed by the study coordinator during the weekly telephone contact | ||||||

| •Partial Harvey Bradshaw Index (pHBI) | X | X | X | X | X | X |

|

| ||||||

| Biological Measures | ||||||

| •C-reactive protein (CRP) | X | X | ||||

| •Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | X | X | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Daily Diary (DD) | ||||||

| •Dietary intake | X | X | X | X | ||

| •Gastrointestinal output–quantity and characteristics | X | X | X | X | ||

| •Medication record | X | X | X | X | ||

|

| ||||||

| Weekly telephone contact to assess adherence to study and adverse event assessment | X | X | X | X | ||

|

| ||||||

| Debrief study participant regarding group assignment and diet instruction | X | |||||

Demographics

Data were collected including age, marital status, education, ethnicity, and race.

Health History Form

A health history form was used to collect information relevant to CD history at screening and the information was reviewed at baseline. This form included length of time since diagnosis, history of abdominal surgery, history and pharmacologic management of CD, and the presence of any non-CD inflammatory conditions during the previous 4 weeks, such as a cold or urinary tract infection.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ)

The IBDQ was developed by Guyatt, et al. (Guyatt et al., 1989) for the purpose of providing an instrument to examine HQoL in individuals with IBD, recognizing the broad range of problems experienced by these individuals. The IBDQ is a 32-item Likert-type rating scale conceptually rooted in the importance of measuring subjective aspects of IBD-specific health status in conjunction with objective aspects of IBD symptoms. The questionnaire asks the participant to answer the questions based on symptoms during the past 2 weeks. The four dimensions of HQoL included in the IBDQ are bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional function, and social function (Guyatt et al., 1989). Each question is scored on a 7-point scale from 1 (worst) to 7 (best). The sum of the individual scores gives the questionnaire total, with total scores ranging from 32 to 224 (Irvine, 1999). Higher scores represent better IBD-specific HQoL. The level of measurement is a ratio. The cutoff value for clinical remission has been set at ≥170 points and a ≥32-point change in score is considered to be a clinically significant response (Hlavaty et al., 2006).

Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI)

The HBI was developed by Harvey and Bradshaw (1980) for the purpose of simplifying the measurement of CD activity in CD management and research. This simple index is based on five items, including: (a) general well-being [0 = very well, 1 = slightly below par, 2 = poor, 3 = very poor, 4 = terrible]; (b) abdominal pain [0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe]; (c) number of liquid stools per day [0 = 0 liquid stools, 1 = 1–2 liquid stools, 2 = 3–4 liquid stools, 3 = 5–6 liquid stools, 4 = 7–8 liquid stools, 5 = >8 liquid stools]; (d) abdominal mass [0 = none, 1 = dubious, 2 = definite, 3 = definite and tender]; and (e) complications, scored 1 point per item [arthralgia, uveitis, erythema nodosum, aphthous ulcers, pyoderma gangrenosum, anal fissure, new fistula, or abscess].

The partial Harvey Bradshaw Index (pHBI) takes into account the first three items (general well-being, abdominal pain, and number of liquid stools) and has been used in previous studies to assess clinical response without the need for a clinic visit (Markowitz, Grancher, Kohn, Lesser, & Daum, 2000; Sparrow, Hande, Friedman, Cao, & Hanauer, 2007). In this study, the pHBI was calculated to determine study eligibility using a cut-off of ≥3 but not >9 (Markowitz et al., 2000). A pHBI was also collected during the weekly telephone calls by the study coordinator from weeks 1 through 4.

Biological Measures

C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), biomarkers of systemic inflammation, were collected and assayed at baseline and week 4 for all study participants to assess any change in inflammation levels that may have occurred during the dietary intervention.

Daily Diary (DD)

The DD was given to all participants at baseline to provide a mechanism for recording daily dietary intake, GI output, and any medications taken but not listed as routine on the health history form. Dietary intake records included quantity and pre-specified characteristics of both foods and fluids. The GI output record included time, estimated amount, and pre-specified characteristics of stool, based on the pictorial Bristol Stool Scale that was placed in the front of the DD for convenient reference as needed (Riegler & Esposito, 2001). The medication record included drug name, dosage, time, and purpose of use. The purpose of the DD was two-fold. First, the DD assisted all study participants in focusing on adherence to the dietary instructions provided; second, the DD provided a record of GI function to which the participant could refer when completing the IBDQ.

Dietary Instruction

Each participant received dietary instructions in the form of a take-home sheet that was printed in the front of the DD. The instructions in the intervention group DD included specific instructions and general tips compiled from the author’s experiences working with individuals who have used whole wheat bran consumption and reduced refined carbohydrate intake for CD symptom control. Examples of specific instructions were (a) to eat one packet of whole wheat bran cereal (½ cup) each day (supplied by the study coordinator) and (b) to drink at least 48 ounces of unsweetened fluids each day. Examples of general tips included (a) ideas for saving money while purchasing nutritious whole foods and (b) how to recognize added sugar in commercial food products. The instructions in the control group DD included specific instructions and general tips suggested by experiences of individuals who have used trigger identification for CD symptom control and who have avoided consumption of dietary fiber. The instructions for this modified elimination diet were based on avoidance of foods considered problematic by individuals who posted comments in the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America online patient forum. Examples of specific instructions given to individuals in the control group were (a) to avoid whole grains, dairy products, and spicy foods on symptomatic days and (b) to drink at least 48 ounces of fluid each day, but limit fluids to sips within 30 minutes of meals. Examples of general tips were (a) how to recognize whole grain food products and (b) how to calculate grams of fiber consumed each day.

Statistical Analyses

Feasibility was determined by the rate of patient accrual over time using the proposed sampling criteria, the percentage of eligible participants who chose to participate, participant attrition over time, and reasons for attrition. In addition, participant interviews were conducted to determine patient acceptance and potential limitations of the protocol.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and baseline study variables. Group differences on demographics and baseline study variables were tested in SPSS v. 20.0, using chi square for categorical variables and independent t-tests for continous variables. In spite of the small sample size, assumptions of the statistical tests were generally met. Repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) tests were used to analyze Aims 2 and 3, given that the HQoL and the pHBI were measured at multiple time points (3 for the HQoL and 5 for the pHBI). For the secondary aim, investigating group differences on inflammatory markers, separate ANCOVAs were used for each dependent variable (CRP and ESR) with group as the independent variable and the respective baseline value of each inflammatory marker as the covariate.

Results

Analysis of Aim 1

During the time allotted for recruitment, seven individuals met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Weekly chart reviews of scheduled clinic patients revealed that the limiting factor for study recruitment was the need for active symptoms (pHBI score ≥3) in the presence of non-biologic, stable drug therapy. In other words, for most patients seen in the clinic who reported active CD symptoms, biologic therapy was already in use, or their drug regimen was changed in an attempt to ameliorate symptoms. Those patients who did meet all the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and were informed of the study by the clinic nurse or doctor, were interested in learning more about the study and subsequently enrolled.

The seven study participants who enrolled in the study were randomized to one of two groups: four participants to the interventional diet instruction group and three to the attention control diet group. All of the enrolled participants completed all aspects of the protocol and gave permission for the inclusion of their data in the study analysis.

Participants in the wheat bran intervention group found the required changes in the diet to be feasible. They understood the dietary fiber information and appreciated the relevance of the information to the symptoms of CD. All participants were willing and able to efficiently alter daily dietary intake in response to the instructions they received. The intervention diet was well-tolerated and there were no negative effects reported from consuming whole wheat bran cereal or from refined carbohydrate restriction.

Participants in the control group also understood the relevance of the diet information and instructions provided to them. They also were willing to participate and easily followed the directions they were given. No negative effects were noted among participants in the control group who were asked to avoid foods commonly thought to be offending agents in CD, such as whole grains, dairy products, and spicy foods.

The baseline characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics or in baseline study measures between groups.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Active Treatment n = 4 | Attention Control n = 3 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yrs: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 33.3(17.1) | 24.33 (6.7) | 0.438 |

| Gender: | |||

| Female (%) | 4 (100.0) | 3 (66.7) | 0.212 |

| Male (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Education in yrs: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (2.2) | 15.7 (2.1) | 0.846 |

| Marital categories: n(%) | |||

| Married (%) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0.659 |

| Not married (%) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Racial Group: n (%) | |||

| Caucasian (%) | 3 (75%) | 3 (100) | 0.350 |

| Minority (%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Baseline IBDQ score: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 158.3(20.1) | 152.7 (32.0) | 0.786 |

| Baseline pHBI score: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.5) | 0.602 |

| Baseline ESR: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.8 (33.5) | 28.7 (2.6) | 0.965 |

| Baseline CRP: | |||

| Mean (SD) | 35.3 (52.4) | 18.2 (28.3) | 0.636 |

SD, standard deviation; IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; pHBI, partial Harvey Bradshaw Index; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein

Analysis of Aims 2 and 3

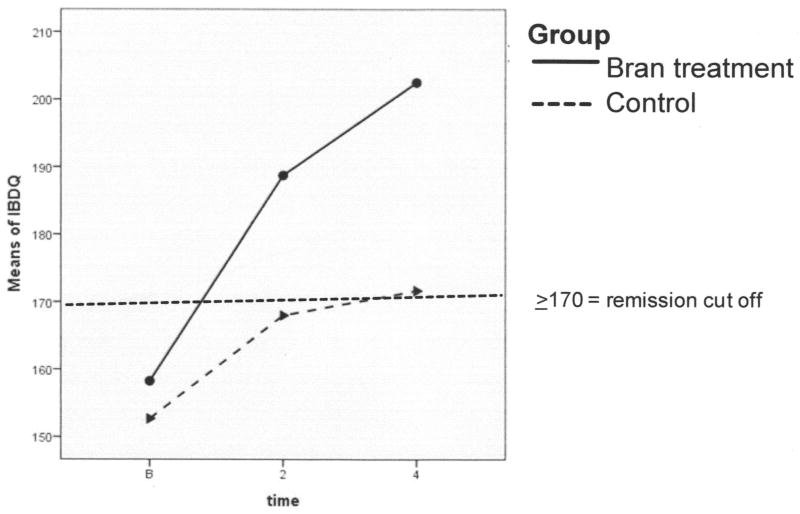

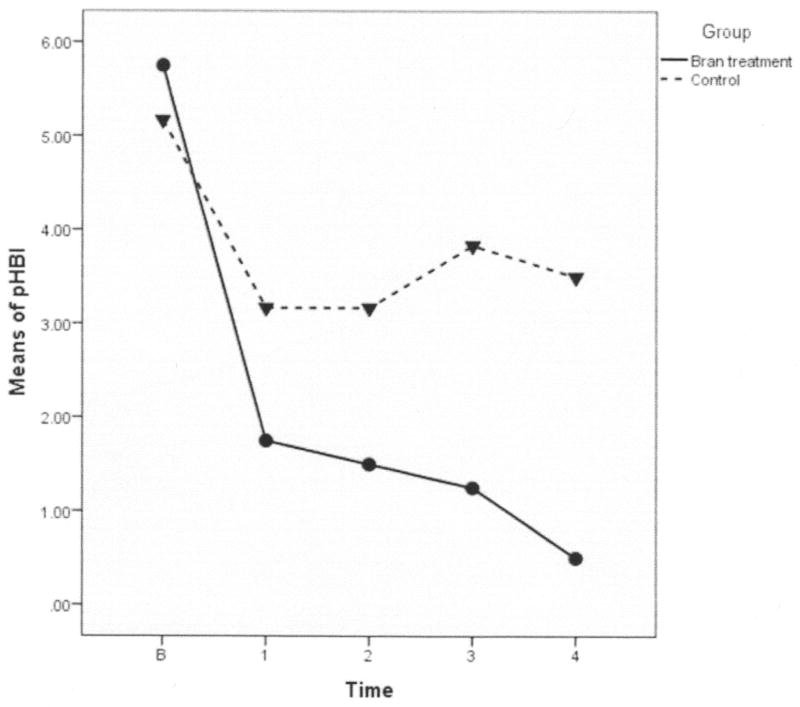

Statistically significant group by time differences were found in both IBDQ and pHBI. These differences indicate that although all participants improved to a degree, the improvements were greater over time in the whole wheat bran intervention group compared to the attention control group. The wheat bran group had increased scores on the IBDQ over time (indicating greater improvement in HQoL) than those in the attention control group (p = 0.028; Figure 1). The pHBI scores decreased significantly over time in the active wheat bran intervention group, demonstrating improved GI function compared to participants in the attention control group (p = 0.008; Figure 2).

Figure 1. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) Scores During Study.

The IBDQ measures Crohn’s disease-specific health-related quality of life related to bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional function, and social function. All participants in both groups began the study under the cutoff point for clinical remission (≥170 points). Participants in the intervention group achieved clinical remission by week 2 and continued to improve substantially through the end of the study period. Scores for participants in the active intervention group increased by 44 points, an increase exceeding the change in score considered to be a clinically significant response (≥32-point change). The control group improved by 19 points, an increase not considered to be clinically significant.

Figure 2. Partial Harvey Bradshaw Index Graph (pHBI).

The pHBI measures Crohn’s disease symptoms (general well-being, abdominal pain, and liquid stools). This graph shows that the high fiber (bran) treatment group and the control group mean scores were close at baseline. Mean scores for both groups dropped during the first week, the intervention group dropping more steeply. From week 1 until the end ot the study, the control group means did not drop further and in fact increased slightly. Because all participants in the intervention group scored a ‘zero’ on the pHBI at week 4, the pHBI scores were transformed by adding 0.5 to allow analysis.

Not only were there statistically significant group differences over time, but there also were clinically significant differences in HQoL and GI function (Figures 1 and 2). A ≥32-point change in IBDQ score is considered to be a clinically significant response (Hlavaty et al., 2006), and in our sample, the mean IBDQ score in the active intervention group increased by 44.25 points, while the increase was only 19 points in the attention control group (not clinically significant). Clinical significance also was demonstrated by the pHBI scores, because the active intervention group participants all scored a ‘zero’ on the index at week 4, indicating that there were no lingering symptoms of impaired general well-being, abdominal pain, or liquid stools after 4 weeks of consuming a daily serving of whole wheat bran cereal. In contrast, participants in the control group all scored a ‘three’ on the pHBI at week 4, indicating that these individuals were still exhibiting lingering symptoms of diminished well-being, abdominal pain, and/or liquid stools.

Participants in the active wheat bran intervention group reported a number of noteworthy observations in follow-up interviews. One female participant who had not been able to form a normal stool (except while taking prednisone) during the 3 years prior to study enrollment began passing normally formed stools without prednisone by the end of the first week and continued to do so for the remainder of the study. Another female participant in the intervention group who was consistently passing normally formed stool during the second half of the study reverted back to diarrhea on day 30 after consuming no wheat bran on day 29. This participant, as well as the other three participants in the intervention group, stated at the end of the study that they intended to maintain daily wheat bran consumption, after completing the study, using the commercially available cereal that is available in regular grocery stores.

Observations of participants in the control group also were noted, and these participants expressed mixed impressions as they summarized the effect of the diet they were instructed to follow during the study. One participant reported better awareness of the foods he was eating, and he thought he might subsequently be better able to recognize problematic foods as a result of participating in the study. Another participant said her “pain seemed to subside more frequently as the month progresssed” and her “stool formation seemed to be more usual.” However, the third participant said, “I was able to see what a low-fiber diet did to my Crohn’s, but overall, I don’t think that my symptoms decreased or were made better.” One participant in the control group said he “may continue to write down what I eat” in an attempt to monitor intake; however, none of the participants in the control group expressed an intention to continue with the dietary modifications required for the study.

The observed power and effect sizes were impressive for a small sample. The observed power for pHBI and IBDQ analyses were 0.89 and 0.69, respectively. The partial eta squared values for the pHBI and IBDQ analyses were 0.48 and 0.51, respectively, indicating moderate effect sizes.

Analysis of the Secondary Aim

Separate ANCOVAs were run for CRP and ESR results. CRP results should be viewed cautiously because one CRP specimen in the control group was lost resulting in missing data for this value. After controlling for the baseline value of the appropriate inflammatory marker (baseline CRP or baseline ESR), there were no statistically significant group differences on either CRP (p = .125) or ESR (p = .788) at 4 weeks.

Discussion

This study provides important preliminary data regarding the feasibility of teaching individuals with CD to implement a high fiber diet including consumption of whole wheat bran cereal and refined carbohydrate restriction. Demonstrated acceptance of this interventional diet, its ease of implementation, tolerability, and affordability for participants in this sample suggest that this dietary instruction is feasible for use in clinical CD research. No previous fiber-related CD study was found to have focused on dietary modifications including consumption of whole wheat bran cereal and refined carbohydrate restriction. Previous fiber-related research studies either focused on diet and overall fiber intake, or these studies focused on testing a specific fiber supplement (such as a powder or capsule) without changing the foods participants ate (Benjamin et al., 2011; Chapman-Kiddell et al., 2010). Thus, the feasibility of using the whole wheat bran dietary instruction as a study variable was previously unknown.

Perhaps because of a placebo effect or more attention paid to diet and symptoms, all study participants showed improvements in the IBDQ and pHBI. However, the trajectory of improvements in scores was less steep for participants in the control group compared to the intervention group (Figures 1 and 2). After the first week, improvements in the control group leveled. In the case of the pHBI means for the control group, there was a reversal in trajectory, indicating a worsening of symptoms for these participants who were not instructed to follow the whole wheat bran intervention diet (Figure 2).

The findings of statistically significant differences and clinically important changes in HQoL and GI function over time in the whole wheat bran group compared to the attention control group are in contrast to results of a recent investigation of a fractionated fiber extract. Benjamin et al. (2011) tested the fiber supplement fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS) in a sample of individuals with active CD, without changing the foods participants ate. Although inflammatory cytokine markers improved in the group that received FOS, GI symptoms worsened and there was a dropout rate of 26% for individuals in the active intervention group.

Such contrast in findings between the FOS study and the current whole wheat bran study speaks to the heterogeneity of dietary fibers and the heterogeneity of the physiological effects of differing dietary fibers in the GI tract. The fact that a single fiber extract was not tolerated in the Benjamin et al. (2011) study does not nullify the potential for a different dietary fiber to be tolerated, as was demonstrated in the current wheat bran study.

Whereas Benjamin et al. recommended against further testing of complex, fermentable carbohydrates in individuals with active CD symptoms, the findings in the current whole wheat bran study suggest the opposite. Wheat bran, which is a naturally complete fiber, is a complex, fermentable fiber that should be further tested in individuals with active CD symptoms. Follow-up studies are needed because the intervention was well-received by participants and important, relevant questions have been raised by the current findings. These questions relate to the potential for replication in a larger study, testing the intervention in a more heterogenous sample of individuals with CD, and examining potential mechanisms producing the observed effects.

The current study is a first step in a re-investigation of the Burkitt (1984) fiber hypothesis of CD. Three potential mediators of the effect of wheat bran consumption on HQoL and GI function are hypothesized but not measured in this feasibility study. These potential mediators are the supply of short-chain fatty acids, the balance of microflora, and gastrointestinal transit time. Future research to investigate actual changes in potential mediators following diet modification may contribute to a better understanding of the effects of whole wheat bran consumption in the context of CD. Findings from intermediate studies can then be used to better inform study designs of larger randomized clinical trials of the described whole wheat bran diet intervention.

Limitations

The current study was limited by a small sample size. Further study in a larger sample is required to verify that the improvement in the intervention group was not just the natural history of IBD/CD. The decision to exclude individuals using biologic therapies was driven by the constraints of a short time period, because the irregularity of biologic drug administration would have been a confounding variable in this 28-day protocol. Because a high percentage of individuals with CD use biologic therapies, the pool of eligible individuals was much smaller than expected, and design modifications will be needed to permit inclusion of these individuals. For example, a longer study that spans years rather than days can successfully include individuals using biologic therapies by using relapse rates or remission maintenance rates to determine study outcomes. Or because biologic drugs do not target gut microbes, future studies can include individuals using biologic drugs if the primary aim of the study is to measure changes in the microbiota. The potential importance of this design has been substantially enhanced by work conducted during the past 5 years that has uncovered distinctive features of dysbiosis associated with active CD versus inactive CD and individuals not diagnosed with CD (Ferguson, 2012). The need to understand the effect of diet on microbial composition is also heightened by increasing recognition that alterations in microbial composition can up-regulate the mucosal immune response and disrupt epithelial function (Sartor, 2008). A third approach for including individuals using biologic therapies may be to study the symptom patterns of individuals who experience increased CD activity during the time period preceeding scheduled infusions. A study conducted in a sample of individuals being treated with biologic drug infusions could be designed to compare the symptom patterns of individuals who consume wheat bran cereal and restrict refined carbohydrates to the symptom patterns of individuals who do not.

This current study was also limited by a lack of meaningful objective biological measures. The biological measures used, CRP and ESR, measure systemic inflammation, not specifically GI inflammation. Additionally, the usefulness of these systemic measures was diminished further by the lack of power associated with the small sample size. Adequately funded future studies will be able to overcome this limitation by increasing sample size using strategies already described and by adding more meaningful measures such as fecal inflammatory markers, calprotectin and/or lactoferrin. In addition, a longer study may be needed to see differences in fecal inflammatory markers if changes were to occur as a result of consuming wheat bran cereal and restricting refined carbohydrates over time.

Generalizability is limited in the current study. Because only women were randomized to the intervention group, it is unknown if men would have had the same results. Also, findings from this study cannot be generalized to groups of individuals with CD who differ by gender, race, ethnicity, and educational background. Also it is not known if the results in this study sample would be replicated in a sample of individuals who were excluded from the study, especially those using biologic therapies (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, infliximab, and natalizumab) or individuals with more severe CD symptoms (pHBI >9).

Conclusion

The current study succeeded in systematically exploring the feasibility and effects of specific dietary instructions focusing on the addition of whole wheat bran consumption as an adjunctive intervention in a sample of individuals with CD. The results demonstrate that these participants were able to process and use the information to make changes in their daily diets that they viewed as beneficial to their health. No side effects occurred with the addition of whole wheat bran cereal and reduction of refined carbohydrates in the study participants. Participants appreciated being provided dietary information and the opportunity to use the information to see for themselves the effects of whole wheat bran cereal consumption with refined carbohydrate restriction. Participants in this study appreciated the time spent by a health care professional to help them delve deeply into the complex relationship between food and the symptoms of CD, and they valued the opportunity to judge the results for themselves. Although CD may remain incurable at present, the current study provides evidence that diet modification, specifically an alteration in the types of carbohydrates consumed on a daily basis, may be a welcomed complementary therapy for those individuals who suffer lingering GI disruption associated with CD and who desire restoration of continent bowel function.

Today, gastroenterolgy nurses who learn about the physiologic effects of cereal fiber in the intestinal tract will have expanded opportunity for leadership. For example, the water-holding capacity of wheat bran and the benefits of butyrate-forming fermentation are important pieces of information that are not currently given to patients with Crohn’s disease when they ask questions about diet, yet the information is relevant. Nurses often spend more time with patients than do physicians, and nurses interact with patients earlier in the disease process than do dietitians; therefore, nurses are often better-positioned to educate patients regarding the role of diet. Furthermore, by taking the lead in disseminating information about beneficial physiologic effects of cereal fiber, gastroenterology nurses may advance understanding among other members of the health care teams that work together to help individuals with CD.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grant number 5-F31-NRO11121 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NINR.

Contributor Information

Carol S. Brotherton, Email: csb8b@virginia.edu, University of Virginia, Center for the Study of Complementary and Alternative Therapies, Research Associate; P.O. Box 800782, Charlottesville, Virginia 22908-0782; 1-703-282-1656 (telephone); 1-434-243-9938 (FAX).

Ann Gill Taylor, Email: agt@virginia.edu, University of Virginia, Center for the Study of Complementary and Alternative Therapies, Center Director; P.O. Box 800782, Charlottesville, Virginia 22908-0782; 1-434-924-0113 (telephone); 1-434-243-9938 (FAX).

Cheryl Bourguignon, Email: cb2n@virginia.edu, University of Virginia, Center for the Study of Complementary and Alternative Therapies, Associate Professor of Nursing and statistician; P.O. Box 800782, Charlottesville, Virginia 22908-0782; 1-434-924-0113 (telephone); 1-434-243-9938 (FAX).

Joel G. Anderson, Email: jga3s@virginia.edu, University of Virginia, Center for the Study of Complementary and Alternative Therapies, School of Nursing, Assistant Professor of Nursing; P.O. Box 800782, Charlottesville, Virginia, 22908-0782; 1-434-243-9936 (telephone); 1-434-243-9938 (FAX).

References

- Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Rioux JD, Barmada MM. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(8):955–962. doi: 10.1038/NG.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin JL, Hedin CRH, Koutsoumpas A, Ng SC, McCarthy NE, Hart AL, Forbes A. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fructo-oligosaccharides in active Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2011;60(7):923–929. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.232025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein CN. Epidemiologic clues to inflammatory bowel disease. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2010;12:495–501. doi: 10.1017/S0010417500015334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton CS, Taylor AG, Herman GB. High fibre diet in the treatment of Crohn’s disease flare: A case study. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton CS, Taylor AG. Dietary fiber information for individuals with Crohn’s disease: Reports of gastrointestinal effects. 2013 doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e3182a67a9a. Manuscript in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson LR. Potential value of nutrigenomics in Crohn’s disease. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012:1–11. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.41. Online publication (March 13, 2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine KD, Schiller LR. AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(6):1464–1486. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70513-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, Singer J, Williams N, Goodacre R, Tompkins C. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(3):804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavaty T, Persoons P, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, Pierik M, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Evaluation of short-term responsiveness and cutoff values of inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire in Crohn’s disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2006;12(3):199–204. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217768.75519.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine EJ. Development and subsequent refinement of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: A quality-of-life instrument for adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 1999;28(4):S23–S27. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine EJ, Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Thomson ABR, Persson T. Quality of life rapidly improves with budesonide therapy for active Crohn’s disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2000;6(3):181–187. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalha IS, Sellin JH. Short-chain fatty acids. In: Sartor RB, Sandborn WJ, editors. Kirsner’s inflammatory bowel diseases. 6. New York, NY: Saunders; 2004. p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- Kripke SA, Fox AD, Berman JM, Settle RG, Rombeau JL. Stimulation of intestinal mucosal growth with intracolonic infusion of short-chain fatty acids. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 1989;13(2):109–116. doi: 10.1177/0148607189013002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein GR, Targan SR, Dubinsky MC, Rotter JI, Barken DM, Princen F, Chuang E. Combination of genetic and quantitative serological immune markers are associated with complicated Crohn’s disease behavior. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2011;17(12):2488–2496. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Fermentation in the human large intestineits physiologic consequences and the potential contribution of prebiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(Supp 3):S 120–S 127. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31822fecfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz J, Grancher K, Kohn N, Lesser M, Daum F. A multicenter trial of 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone in children with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(4):895–902. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.18144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata A, Usami M, Miyoshi M. Short-chain fatty acids alter tight junction permeability in intestinal monolayer cells via lipoxygenase activation. Nutrition. 2005;21(7–8):838–847. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsk V, Lemberg DA, Grewal K, Barker CC, Schreiber RA, Jacobson K. Inflammatory bowel disease in the South Asian pediatric population of British Columbia. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102(5):1077–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryde SE, Duncan SH, Hold GL, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. The microbiology of butyrate formation in the human colon. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2002;217(2):133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegler G, Esposito I. Bristol scale stool form. A still valid help in medical practice and clinical research. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2001;5(3):163–164. doi: 10.1007/s101510100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):577–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segain JP, Raingeard de la Bletiere D, Bourreille A, Leray V, Gervois N, Rosales C, Galmiche JP. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFkB inhibition: Implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2000;47:397–403. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow MP, Hande SA, Friedman S, Cao D, Hanauer SB. Effect of allopurinol on clinical outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease nonresponders to azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5(2):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm A, Dignass AU. Epithelial restitution and wound healing in inflammatory bowel disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(3):348–353. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topping DL, Clifton PM. Short-chain fatty acids and human colonic function: Roles of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(3):1031–1064. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nakahigashi M, Saniabadi A. Review article: Diet and inflammatory bowel disease–epidemiology and treatment. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2009;30(2):99–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]