Abstract

Coordinated programmes of resolution are thought to initiate early after an inflammatory response begins, actively terminating leucocyte recruitment, allowing their demise via apoptosis and their clearance by phagocytosis. In this review we describe an event that could be implicated in the resolution of inflammation, i.e. the establishment of a refractory state in human neutrophils that had phagocytosed apoptotic cells. Adherent neutrophils challenged with apoptotic cells generate neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), filaments of decondensed chromatin decorated with bioactive molecules that are involved in the capture of various microbes and in persistent sterile inflammation. In contrast, neutrophils that had previously phagocytosed apoptotic cells lose their capacity to up-regulate β2 integrins and to respond to activating stimuli that induce NET generation, such as interleukin (IL)-8. A defective regulation of NET generation might contribute to the persistent inflammation and tissue injury in diseases in which the clearance of apoptotic cells is jeopardized, including systemic lupus erythematosus and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis.

Keywords: inflammation, neutrophils, phagocytosis

OTHER ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THIS SERIES

Dying autologous cells as instructors of the immune system. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 1–4.

Anti-dsDNA antibodies as a classification criterion and a diagnostic marker for systemic lupus erythematosus: critical remarks. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 5–10.

The effect of cell death in the initiation of lupus nephritis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 11–16.

Desialylation of dying cells with catalytically active antibodies possessing sialidase activity facilitate their clearance by human macrophages. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 17–23.

Developmental regulation of p53-dependent radiation-induced thymocyte apoptosis in mice. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 30–38.

Loading of nuclear autoantigens prototypically recognized by systemic lupus erythematosus sera into late apoptotic vesicles requires intact microtubules and myosin light chain kinase activity Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 39–49.

Low and moderate doses of ionizing radiation up to 2 Gy modulate transmigration and chemotaxis of activated macrophages, provoke an anti-inflammatory cytokine milieu, but do not impact upon viability and phagocytic function. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 50–61.

Vessel-associated myogenic precursors control macrophage activation and clearance of apoptotic cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 62–67.

Acetylated histones contribute to the immunostimulatory potential of neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 68–74.

Unconventional apoptosis of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN): staurosporine delays exposure of phosphatidylserine and prevents phagocytosis by MΦ-2 macrophages of PMN. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 75–84.

Introduction

Neutrophils are the most abundant circulating phagocytes and represent an inborn circulating system for the clearance of particulate substrates, such as microbes. A ‘tether and tickle’ mechanism controls the clearance of other particulate substrates, apoptotic cells and activated platelets: bridging receptors function by tethering the substrate to the phagocyte, whereas the recognition of phosphatidylserine recruits signals that initiate the uptake [1]. Inefficient clearance results in the accumulation of cell remnants and is involved in the initiation of systemic autoimmunity and autoinflammation [2–5].

Neutrophil effector functions comprise the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [6]. NETs are decondensed chromatin filaments decorated with histones and neutrophil anti-microbial proteins such as elastase, myeloperoxidase and defensins [6,7]. Deregulated NET formation/degradation represents a source of intracellular antigens that can be presented in inflammatory contexts that favour their immunogenicity. Indeed, deregulated NET generation and processing have been associated with several autoimmune diseases [8–14]. Here, we report evidence that supports the existence of a finely tuned regulatory loop by which neutrophils that had successfully phagocytosed apoptotic cells lose their ability to respond to inflammatory stimuli and in particular to generate NETs.

Materials and methods

Neutrophils activation and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells

Human lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL) were kindly provided by Dr Heltai (Milan) and submitted to apoptosis by ultraviolet (UV) irradiation (apoptotic LCL, a-LCL) [15]. Apoptosis was verified by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy [15]. Human neutrophils from healthy donors were purified as described [16–19] and resuspended in HEPES–Tyrode buffer containing CaCl2 (1 mM). Neutrophils (5 × 106/ml) were incubated with a-LCL for 10 min at a 1:1 ratio at 37 or 4°C. When indicated, a-LCL had been treated previously with recombinant chicken annexin A5 (10 μg/ml final concentration), produced and characterized as described [20]. When indicated, a-LCL were loaded with the fluorescent dye carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (equivalent to Alexa 488, green). Cells were permeabilized using the Fix & Perm kit (Caltag, Buckingham, UK). Phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry and verified by confocal microscopy [17,21]. CD18 expression was assessed by flow cytometry after staining neutrophils with the specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) (clone 7E4; Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy), as described previously [19].

In-vitro NET formation

Neutrophils (5 × 106) that had phagocytosed or not apoptotic LCL were placed on poly-l-lysine-coated slides for 20 min at 37°C. Adherent neutrophils were then stimulated with recombinant interleukin (IL)-8 (100 ng/ml), challenged with apoptotic cells or left untreated. Plates were centrifuged and fixed with Thrombofix (Beckman Coulter, Milan, Italy). Supernatants were further cleared by centrifugation and frozen until determination of DNA amounts by the Quantification Kit Fluorescence assay (Sigma, Milan, Italy) [17,21].

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy imaging was carried out as described previously [17,21]. Briefly, slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with mAbs against cathepsin G (Alexa Fluor 541, red) and DNA was counterstained with Hoechst 33342 without any permeabilization step. Confocal images were collected with a Leica TCS SP2 laser scanning confocal microscope with multi-line laser excitation: 405 nm, 488 nm, 543 nm and 633 nm. Dyes were selected based on distinct absorption peaks, each corresponding closely to available laser lines. We acquired channels sequentially to prevent artefacts due to cross-talk events.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. All statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism (version 5·0; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA), using analysis of variance (anova) followed by multiple pairwise comparison tests, with differences being considered significant for P < 0·05.

Results and discussion

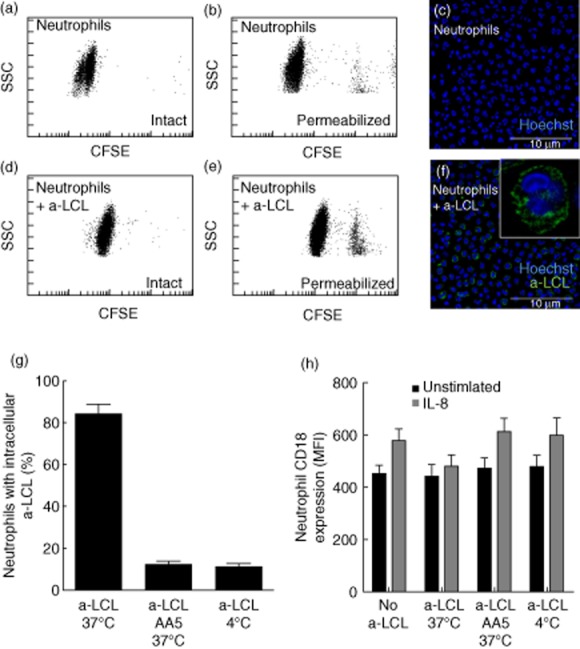

Apoptotic cells are readily ingested by resting neutrophils upon incubation at 37°C at a 1 : 1 phagocyte : apoptotic substrate ratio (Fig. 1a–g): >80% of neutrophils had phagocytosed at least one apoptotic cell at the end of the assay. Phagocytosis abates at 4°C, i.e. in conditions in which the actin-based filament network does not rearrange, or when apoptotic cells have been treated previously with annexin A5 (Fig. 1g). Under the latter conditions, the rate of phagocytosis drops from 84·4 ± 11 to 9·9 ± 3·2% (P < 0·0001). Annexin A5 binds to exposed phosphatidylserine, forming a three-dimensional crystalline lattice, thus inhibiting events downstream of phosphatidylserine recognition [20,22]. This hindrance abolishes internalization, but does not interfere with adhesive interactions that actually appear paradoxically increased, because tethered apoptotic substrates are not removed (after a 10-min interaction at 37°C 67·1 ± 11·2% neutrophils have tethered annexin A5-treated apoptotic cells versus 13·0 ± 5·3% neutrophils with adherent untreated apoptotic cells). The role of phosphatidylserine in selectively triggering internalization of particulate substrates by mononuclear and polymorphonuclear phagocytes without directly interfering with their recognition has been demonstrated in other model systems (e.g. see [20,21,23]).

Fig. 1.

Neutrophil clearance of apoptotic cells. (a–f) Representative flow cytometry plots (a,b,d,e) and confocal microphotographs (c,f) of neutrophils phagocytosing apoptotic cells [apoptotic lymphoblastoid cell lines (a-LCL)]. Internalization of fluorescent apoptotic cells [carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-a-LCL] was quantified by flow cytometry (Gallios, Beckman Coulter) and confirmed by confocal microscopy. (g) CFSE-a-LCL were incubated with neutrophils (1 : 1 ratio) for 10 min at 37°C (a-LCL 37°C). Phagocytosis was aborted by the treatment of a-LCL with recombinant annexin A5 (a-LCL AA5 37°C) or by incubation at 4°C (a-LCL 4°C). (h) The CD18 expression in the absence (filled bars) or in the presence of interleukin (IL)-8 on the neutrophil cell surface was assessed by flow cytometry, as described in the Methods. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean of five independent experiments performed with different healthy subjects.

The presence of β2 integrins on the membrane surface of neutrophils that had internalized apoptotic cells does not increase upon stimulation with interleukin (IL)-8 (Fig. 1h), indicating that they are at least partially unresponsive to selected stimuli. Indeed, the responsiveness of neutrophils to IL-8 is maintained when phagocytosis abates by treatment with annexin A5 or by challenging neutrophils with apoptotic cells at 4°C. The results indicate that actual internalization of the apoptotic cell is required to convert neutrophils in an unresponsive state, while the activation of tethering receptors is apparently dispensable.

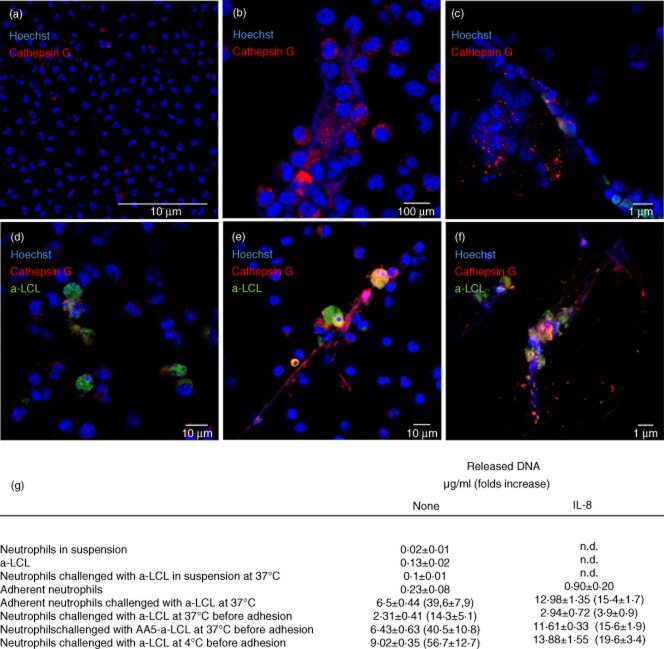

NET generation is gaining increasing attention as a means by which neutrophils exert their effector functions. We failed to observe NET generation when neutrophil and apoptotic cell interactions occur in suspension (Fig. 2g). In contrast, when neutrophils are allowed to adhere before the challenge with apoptotic cells, phagocytosis is minimal (not shown) while NET generation is prominent (Fig. 2g). Using immunofluorescence, the presence of NETs was monitored assessing the neutrophil granule enzyme, cathepsin G decorating extracellular DNA filaments (Fig. 2a–f) and quantified by the determination of DNA in the culture supernatant (Fig. 2g). Adherent neutrophils challenged with apoptotic cells generate NETs, with an efficiency sevenfold greater compared to those stimulated with IL-8 (6·5 ± 0·4 versus 0·9 ± 0·2 μg DNA/ml, P < 0·001; Fig. 2), possibly because of a frustrated attempt at phagocytosing the substrate [24–26]. In partial support of this claim, confocal analysis confirms that neutrophils with intracellular apoptotic cells are not involved in NET generation (Fig. 2d). To address this issue more directly, we retrieved neutrophils that had phagocytosed apoptotic cells, allowed them to adhere, and challenged them with IL-8. In these conditions, neutrophils fail to generate NETs which are, in contrast, produced by neutrophils challenged previously with annexin A5-decorated apoptotic cells (Fig. 2g).

Fig. 2.

Reciprocal regulation of phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation. NET formation was monitored by confocal microscopy (a–f) and extracellular DNA amounts determined in cell free-supernatants (g). The red colour refers to cathepsin G (Alexa Fluor 546), the green colour to apoptotic cells [apoptotic lymphoblastoid cell lines (a-LCL)]. DNA was counterstained with Hoechst 33342 without any permeabilization step. (a–f) Representative images of: unstimulated adherent neutrophils (a); adherent neutrophils stimulated with interleukin (IL)-8 (b); adherent neutrophils challenged with apoptotic cells (c); neutrophils that had been challenged with apoptotic cells at 37°C before adhesion on the slides (d); neutrophils that had been challenged before adhesion with apoptotic cells in conditions in which phagocytosis was prevented by annexin A5 (e) or by incubation at 4°C (f). (g) The released DNA was quantified in cell-free supernatants. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean of five independent experiments performed with different healthy subjects; n.d. = not determined.

Taken together, our data indicate that neutrophils that have phagocytosed apoptotic cells appear unresponsive to further stimulation. Disposal of an apoptotic cargo implies a substantial reorganization of the phagocyte intracellular architecture and is linked to a complex metabolic reorganization, the molecular bases of which have been identified [27]. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells instructs the resolution of acute inflammatory processes [28]. It is tempting to speculate that the reduced ability to generate NETs after the clearance of phagocytic cargos might play a role in the termination of potentially noxious ongoing inflammatory events in physiological conditions, restricting neutrophil sensitivity to inflammatory stimuli. Conversely, disruption of this regulatory loop might contribute to the persistent inflammation and tissue damage that are hallmarks of diseases characterized by defective apoptotic cell clearance and excessive NET generation, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated small vessel vasculitis [5,11,29]. In SLE, neutrophils are primed to generate NETs in response to cytokines, immune complexes and autoantibodies [30]. The mechanisms underlying the accelerated and enhanced NET generation have not been elucidated fully. Further studies are warranted to verify whether the failure of neutrophils to phagocytose apoptotic cells and, as a consequence, their failure to enter an unresponsive state might be involved in the natural history of the disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ministero della Salute), RF2009 to A. A. M. and P. R.-Q.; the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR), PRIN 2010 to A. A. M. and FIRB-IDEAS to P. R.-Q.; and the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC IG 11761) to A. A. M. Imaging studies were carried out in ALEMBIC, an advanced microscopy laboratory established by the San Raffaele Scientific Institute and the Vita-Salute San Raffaele University.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hochreiter-Hufford A, Ravichandran KS. Clearing the dead: apoptotic cell sensing, recognition, engulfment, and digestion. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a008748. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrmann M, Voll RE, Zoller OM, Hagenhofer M, Ponner BB, Kalden JR. Impaired phagocytosis of apoptotic cell material by monocyte-derived macrophages from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1241–1250. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1241::AID-ART15>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferri LA, Maugeri N, Rovere-Querini P, et al. Anti-inflammatory action of apoptotic cells in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rovere P, Sabbadini MG, Fazzini F, et al. Remnants of suicidal cells fostering systemic autoaggression. Apoptosis in the origin and maintenance of autoimmunity. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1663–1672. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1663::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M, Manfredi AA, Herrmann M. The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:280–289. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mocsai A. Diverse novel functions of neutrophils in immunity, inflammation, and beyond. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1283–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakkim A, Furnrohr BG, Amann K, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9813–9818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schorn C, Janko C, Krenn V, et al. Bonding the foe – NETting neutrophils immobilize the pro-inflammatory monosodium urate crystals. Front Immunol. 2012;3:376. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight JS, Zhao W, Luo W, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition is immunomodulatory and vasculoprotective in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2981–2993. doi: 10.1172/JCI67390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khandpur R, Carmona-Rivera C, Vivekanandan-Giri A, et al. NETs are a source of citrullinated autoantigens and stimulate inflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:178ra40. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kambas K, Chrysanthopoulou A, Vassilopoulos D, et al. Tissue factor expression in neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophil derived microparticles in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis may promote thromboinflammation and the thrombophilic state associated with the disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203430. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangaletti S, Tripodo C, Chiodoni C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate transfer of cytoplasmic neutrophil antigens to myeloid dendritic cells toward ANCA induction and associated autoimmunity. Blood. 2012;120:3007–3018. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rovere P, Peri G, Fazzini F, et al. The long pentraxin PTX3 binds to apoptotic cells and regulates their clearance by antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;96:4300–4306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maugeri N, Baldini M, Rovere-Querini P, Maseri A, Sabbadini MG, Manfredi AA. Leukocyte and platelet activation in patients with giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: a clue to thromboembolic risks? Autoimmunity. 2009;42:386–388. doi: 10.1080/08916930902832629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maugeri N, Malato S, Femia EA, et al. Clearance of circulating activated platelets in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2011;118:3359–3366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maugeri N, Franchini S, Campana L, et al. Circulating platelets as a source of the damage-associated molecular pattern HMGB1 in patients with systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity. 2012;45:584–587. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2012.719946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maugeri N, Rovere-Querini P, Baldini MM, et al. Oxidative stress elicits platelet/leukocyte inflammatory interactions via HMGB1: a candidate for microvessel injury in sytemic sclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1060–1074. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bondanza A, Zimmermann VS, Rovere-Querini P, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylserine recognition heightens the immunogenicity of irradiated lymphoma cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1157–1165. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maugeri N, Rovere-Querini P, Evangelista V, et al. Neutrophils phagocytose activated platelets in vivo: a phosphatidylserine, P-selectin, and {beta}2 integrin-dependent cell clearance program. Blood. 2009;113:5254–5265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janko C, Jeremic I, Biermann M, et al. Cooperative binding of annexin A5 to phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cell membranes. Phys Biol. 2013;10:065006. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/10/6/065006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henson PM, Bratton DL, Fadok VA. The phosphatidylserine receptor: a crucial molecular switch? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:627–633. doi: 10.1038/35085094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald B, Urrutia R, Yipp BG, Jenne CN, Kubes P. Intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps capture bacteria from the bloodstream during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenne CN, Wong CH, Zemp FJ, et al. Neutrophils recruited to sites of infection protect from virus challenge by releasing neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park D, Han CZ, Elliott MR, et al. Continued clearance of apoptotic cells critically depends on the phagocyte Ucp2 protein. Nature. 2011;477:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramirez GA, Maugeri N, Sabbadini MG, Rovere-Querini P, Manfredi AA. Intravascular immunity as a key to systemic vasculitis: a work in progress, gaining momentum. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:150–166. doi: 10.1111/cei.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahlenberg JM, Carmona-Rivera C, Smith CK, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil extracellular trap-associated protein activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is enhanced in lupus macrophages. J Immunol. 2013;190:1217–1226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]