Abstract

Benign painful and inflammatory diseases have been treated for decades with low/moderate doses of ionizing radiation (LD-X-irradiation). Tissue macrophages regulate initiation and resolution of inflammation by the secretion of cytokines and by acting as professional phagocytes. Having these pivotal functions, we were interested in how activated macrophages are modulated by LD-X-irradiation, also with regard to radiation protection issues and carcinogenesis. We set up an ex-vivo model in which lipopolysaccharide pre-activated peritoneal macrophages (pMΦ) of radiosensitive BALB/c mice, mimicking activated macrophages under inflammatory conditions, were exposed to X-irradiation from 0·01 Gy up to 2 Gy. Afterwards, the viability of the pMΦ, their transmigration and chemotaxis, the phagocytic behaviour, the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and underlying signalling pathways were determined. Exposure of pMΦ up to a single dose of 2 Gy did not influence their viability and phagocytic function, an important fact regarding radiation protection. However, significantly reduced migration, but increased chemotaxis of pMΦ after exposure to 0·1 or 0·5 Gy, was detected. Both might relate to the resolution of inflammation. Cytokine analyses revealed that, in particular, the moderate dose of 0·5 Gy applied in low-dose radiotherapy for inflammatory diseases results in an anti-inflammatory cytokine microenvironment of pMΦ, as the secretion of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β was reduced and that of the anti-inflammatory cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF)-β increased. Further, the reduced secretion of IL-1β correlated with reduced nuclear translocation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB p65, starting at exposure of pMΦ to 0·5 Gy of X-irradiation. We conclude that inflammation is modulated by LD-X-irradiation via changing the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages.

Keywords: chemotaxis, cytokines, inflammation, macrophage, phagocytosis

OTHER ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THIS SERIES

Dying autologous cells as instructors of the immune system. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 1–4.

Anti-dsDNA antibodies as a classification criterion and a diagnostic marker for systemic lupus erythematosus: critical remarks. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 5–10.

The effect of cell death in the initiation of lupus nephritis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 11–16.

Desialylation of dying cells with catalytically active antibodies possessing sialidase activity facilitate their clearance by human macrophages. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 17–23.

Instructive influences of phagocytic clearance of dying cells on neutrophil extracellular trap generation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 24–29.

Developmental regulation of p53-dependent radiation-induced thymocyte apoptosis in mice Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 30–38.

Loading of nuclear autoantigens prototypically recognized by systemic lupus erythematosus sera into late apoptotic vesicles requires intact microtubules and myosin light chain kinase activity. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 39–49.

Vessel-associated myogenic precursors control macrophage activation and clearance of apoptotic cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 62–67.

Acetylated histones contribute to the immunostimulatory potential of neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 68–74.

Unconventional apoptosis of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN): staurosporine delays exposure of phosphatidylserine and prevents phagocytosis by MΦ-2 macrophages of PMN. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2015, 179: 75–84.

Introduction

Cells of the innate immune system represent the first line of defence against invading pathogens. Macrophages are a crucial component of this system and as specialized phagocytes are responsible for clearing the tissue from pathogens, dying cells or cellular debris. They further recruit other immune cells and finally shut down the inflammatory reactions by modulating the microenvironment with the secretion of distinct cytokines and chemokines. Macrophages are spread all over the body and are located in nearly every tissue with sometimes different phenotypes, depending on the environment [1,2]. For many years, a low/moderate dose (single dose ≤ 1·0 Gy) of ionizing radiation (LD-X-irradiation) has been applied as low-dose radiotherapy (LD-RT) for the treatment of benign inflammatory, hyperproliferative and degenerative diseases, including painful elbow syndrome, painful shoulder syndrome, calcaneodynia, achillodynia and osteoarthritis of the joints. Significant improvement of pain during and after treatment has been described in several clinical studies [3–9]. Because macrophages are key regulators of inflammation, we have been interested to determine whether and how they are influenced by LD-X-irradiation. This is of further importance in terms of radiation protection issues, as exposure to radiation not only increases through medical applications, but also through environmental factors.

Rödel and others have already shown that one of the presumably multiple mechanisms of the induction of anti-inflammation by LD-RT is the reduced evasion of immune cells from the blood into the tissue. Decreased secretion of the chemokine CCL20 and reduced expression of adhesion molecules such as P-, L- and E-selectins were observed and most pronounced in a dose range of 0·3–0·7 Gy [10–13]. This so-called discontinuous dose dependency was also detected when analysing the apoptosis rate in peripheral blood mononuclear cells after LD-X-irradiation showing a peak or plateau at a single dose rate of 0·3–0·7 Gy [14]. As mentioned above, macrophages secrete cytokines that modulate inflammation and thereby the microenvironment. They can be divided into three main subtypes: the first is the classically activated macrophage (M1), showing a proinflammatory phenotype upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation. The second subtype is the more anti-inflammatory alternatively activated macrophage (M2), which is involved in wound healing. The third is a regulatory subtype to which many tumour-associated macrophages (TAM) belong [15].

Preceding studies have already revealed that LD-X-radiation impacts upon macrophages. Alterations in the oxidative burst by the reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced nitrite oxide (NO) production through a suppressed inducible nitrite oxide synthase (iNOS) activation in RAW 264·7 macrophages have been found [16,17]. Radiation-induced ROS indeed triggers apoptosis in monocytes, but does not impact strongly upon the viability of macrophages [18]. Conrad and colleagues observed no significant reduction in the phagocytosis of latex beads by macrophages after irradiation up to 1 Gy [19]. Tsukimoto et al. showed that tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α secretion is decreased in a discontinuous manner after moderate irradiation of macrophages with 0·5 Gy. This was linked to a dephosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2) and a decrease in p38, as well as an increase in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) [20]. Frischholz et al. showed that secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and TNF-α by LPS and monosodium urate (MSU) co-activated primary peritoneal macrophages (pMΦ) of radiosensitive BALB/c mice was reduced after LD-X-irradiation with a single dose of 0·5 or 0·7 Gy [21]. In analogy, Lodermann et al. demonstrated reduced secretion of IL-1β by human THP-1 macrophages, which was associated with reduced translocation of the nuclear factor kappa B RelA (NF-κB p65) subunit as well as a lowered protein amount of MAPK p38 [22].

A second therapeutic approach whereby medicine takes advantage of the effects of X-irradiation is the treatment of cancerous diseases by radiotherapy (RT) with higher single doses (> 1 Gy). The local treatment of tumour masses by RT affects not merely the malignant cells, but also tumour-associated immune cells such as macrophages. In particular, the M1 phenotype, with its potential to initiate or perpetuate inflammation, can play important roles in tumour eradication, but also in the progression of tumours by supporting angiogenesis or tumour-promoting inflammation [23–26]. During tumour progression the M1 phenotype, which is predominantly present in early tumours, changes in established and especially in hypoxic tumours to the TAM phenotype [27,28]. TAM foster recruitment of regulatory T cells and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β or IL-10 [27,29,30]. Both may lead to a reduced reaction of the host's immune system against the tumour cells and in different types of cancer is often associated with a poor prognosis [31–33].

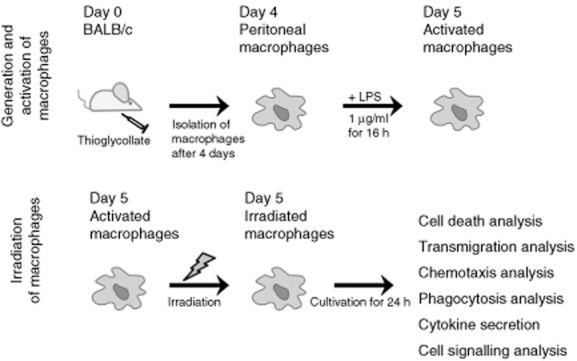

The above-mentioned shows that macrophages and their inflammatory status are crucial in regulating inflammation, and are key players in tumour progression and in the resolution of pre-existing inflammation. Therefore, we aimed to analyse how LPS preactivated pMΦ as a model system for a defined inflammatory phenotype, being present in inflammatory diseases or in (early) tumours, is altered after exposure to low, moderate and high single doses of X-ray (Fig. 1). We focused on viability, transmigration, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, cytokine secretion and the respective inflammatory pathways, as all these events are crucial in modulating inflammation.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setting of generation, activation and irradiation of peritoneal macrophages of BALB/c mice. Primary mouse macrophages were obtained by recruitment into the peritoneum with thioglycollate and consecutive lavage after 4 days. For the ex-vivo assays, the macrophages were activated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), irradiated (0·01, 0·05, 0·1, 0·3, 0·5, 0·7, 1·0, or 2·0 Gy) and cultivated for 24 h. Afterwards, the influence of irradiation of activated macrophages on cell death, transmigration, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, inflammatory cytokine secretion and cell signalling was analysed.

Material and methods

Mice and generation of peritoneal macrophages

BALB/c mice were bred under a sterile atmosphere at the animal facility of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (Franz-Penzoldt-Center). All mice used for the extraction of pMΦ were aged between 30 and 50 weeks and age-controlled for the respective experiments. The animal procedures were approved by the ‘Regierung of Mittelfranken’ and were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA).

pMΦ were generated by injection of 2·5 ml of 4% (w/v) Brewer's thioglycollate broth into the peritoneal cavity, as described previously by Schleicher and Bogdan [34]. This protocol quotes a higher isolation rate with the increased age of the mice and we did not observe age-related changes in cytokine secretion. The recruited pMΦ were isolated 4 days after injection via washing of the peritoneum with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Macrophages were seeded at a density of 2 × 106 per well in low-adherence suspension six-well plates for cell death, transmigration, chemotaxis, cytokine secretion and cell signalling analyses. For analysis of phagocytosis, 8 × 105 pMΦ were seeded in low-adherence suspension six-well plates. All experiments were performed using R10 (RPMI-1640 with stable glutamine, supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum) media. pMΦ were incubated for at least 4 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity, allowing them to adhere properly to the plastic before further treatment.

Treatment of macrophages

Subsequent to seeding and incubation, pMΦ were activated with 1 μg/ml LPS overnight for 16 h. Without changing the medium, the activated pMΦ were irradiated up to a single dose of 2 Gy (0·01, 0·05, 0·1, 0·3, 0·5, 0·7, 1·0 or 2·0 Gy) with an X-ray generator (120 kV, 21·5 mA; GE Inspection Technologies, Hürth, Germany) and incubated for further 24 h before performing the analyses. Figure 1 illustrates the generation, treatment and analyses performed of the pMΦ.

Viability and cell death analyses

Overall viability and metabolic activity of pMΦ were determined using the Alamar Blue assay, according to the manufacturer's instructions (AbD Serotec, Puchheim, Germany). In brief, cells were removed 1 h after irradiation by a cell scraper and by rinsing the bottom of the well with PBS. Of note is that the adherent cells were then combined with the supernatants containing less adherent macrophages. Therefore, non-adherent cells were not lost for the analyses. Afterwards, the cells were transferred to a 96-well plate (5 × 104 cells/well).

After incubation for 24 h, a 1:10 volume of Alamar Blue solution was added, substrate conversion was allowed for 2 h, and fluorescence was measured with a Synergy Mx plate reader (excitation 560 nm, emission 590 nm; Biotek, Bad Friedrichshall, Germany). Fluorescence values were calibrated on the non-irradiated controls (viability = 100%).

Analysis of sub-G1 nuclei as a marker of apoptosis was performed as described by Nicoletti et al. [35]. In brief, cells were isolated, fixed in 70% (v/v) ethanol and stained with 4 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) in the presence of the detergent Triton X-100 0·1% (v/v). Further, plasma membrane disintegration as marker for necrotic cell death was analysed by PI staining (1 μg/ml) in the absence of detergent. For both analyses 2 × 105 cells were used and measurements were performed in triplicate with an XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

Transwell migration assay

The Transwell migration assay was performed as described previously [36]. Briefly, cells were harvested 24 h after irradiation, concentration adjusted to 0·5 × 106 cells/ml and subsequently stained with 1 μM Calcein (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 20 min. After washing, 1·0 × 104 cells were transferred to 5-μm pore-sized 96-well multi-screen-MIC filter plates in a final volume of 80 μl. The filter plates were mounted carefully onto receiver plates containing the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) agonist WKYMVm (200 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Heidelberg, Germany) in a final volume of 310 μl per well. After 3 h of incubation at 37°C, cells that had transmigrated to the lower chamber or the lower side of the pore filter were harvested and lysed in 20 mM HEPES-K pH 7·4, 84 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0·2 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0·2 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) and 0·5% non-ionic, non-denaturating detergent IGEPAL CA-630 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Heidelberg, Germany). Calcein fluorescence was measured at 485 nm excitation and 510 nm emission using a Synergy Mx plate reader (Biotek). The percentage of transmigrated cells was determined on the basis of a calibration curve and measurements were performed in hexaplicate.

Analysis of chemotaxis

The chemotactic response of activated pMΦ was analysed 24 h after irradiation using IBIDI μ-slide two-dimensional chemotaxis chambers (IBIDI, Martinsried, Germany), as described previously [37]. In brief, 24 × 103 cells were loaded onto the observation area of preincubated μ-slides, and adherence was allowed for 30 min at 37°C. Non-adherent cells were washed away and the reservoirs were filled with culture medium. The chemotactic FPR agonist WKYMVm (R&D Systems) was added at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml to the upper reservoir, and μ-slides were mounted onto the preconditioned stage of an AxioObserver Z1 inverted microscope (Zeiss, Goettingen, Germany). Culture medium served as a control. Migration was followed by time-lapse video microscopy for 2·5 h at 5 × magnification at 37°C and 5% CO2. Pictures were taken every 2 min, and migration of 40 randomly selected cells was assessed by manual tracking using ImageJ software (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Euclidian distance was calculated with the IBIDI Chemotaxis and Migration Tool (IBIDI), and the analysis frame was set from 30 to 76 (1·5 h of migration).

Analysis of phagocytosis

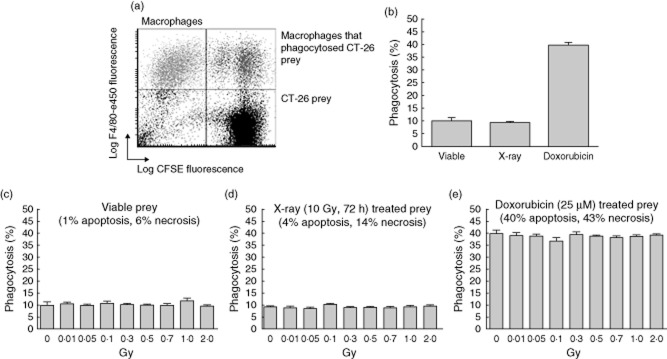

To elucidate whether the phagocytic function of pMΦ is influenced by X-irradiation, a two-colour-based phagocytosis assay was set up in which a carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-stained target (prey) was incubated with F4/80-stained pMΦ. Phagocytosis was equalized, with the cell fraction being positive for both F4/80 and CFSE (Fig. 5a). Briefly, syngeneic CT-26 colorectal tumour cells were stained with CFSE and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity for 16 h. After incubation, the target was treated with X-ray (10 Gy), the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin (25 μM for 24 h and consecutive incubation for 24 h), or mock. X-ray-treated cells were used 72 h, and doxorubicin-treated cells 48 h after treatment. Cell death analysis of the target was performed with annexinV-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (AxV-FITC)/PI-staining. Apoptotic cells were defined as being positive for AxV-FITC binding and negative for PI and necrotic cells for AxV-FITC and PI binding. Target cells, 4 × 106 of CT-26, were incubated with 8 × 105 pMΦ in six-well plates for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. Cells and supernatants were harvested after incubation. The cell suspension was stained with 5 μg/ml CD16/32 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) to avoid unspecific FcγIII/FcγII-receptor antibody binding, and subsequently stained with 0·4 μg/ml of F4/80-e450 (eBioscience) antibody. Measurement was performed in quadruplicate with a Gallios (Beckmann Coulter) flow cytometer.

Fig. 5.

Phagocytic capability of activated peritoneal macrophages after exposure to low, moderate or high dose of X-irradiation. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated peritoneal mouse macrophages of BALB/c mice were irradiated with the indicated doses, cultured consecutively for 24 h, and then served as phagocytes for the two-colour flow cytometry-based phagocytosis assay. CT-26 syngeneic colorectal tumour cells served as target (prey) and were stained with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (a, lower right quadrant). Macrophages were stained with F4/80-e450 antibody and defined as F4/80+ cells (a, upper left quadrant). Macrophages that had phagocytized CFSE-stained CT-26 cells were defined as CFSE+/F4/80+ (a, upper right quadrant). The percentage of phagocytosis of LPS-activated peritoneal macrophages after mock treatment (0 Gy) in dependence of the pretreatment and therefore viability of the target is shown in (b). The influence of X-irradiation of macrophages on the percentage of phagocytosis of target differing in its viability is shown in (c–e). The following target was used: viable CT-26 cells (c), X-ray-treated CT-26 cells (irradiation with 10 Gy and consecutive cultivation for 72 h; d) or doxorubicin-treated CT-26 cells (incubation with 25 μM doxorubicin for 24 h and consecutive cultivation for another 24 h; e). Measurements were performed in quadruplicate and a representative set of experiment results out of three for each target is displayed. Error bars show standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Analysis of cytokine secretion of macrophages

Analyses of cytokines in the supernatants of pMΦ were performed 24 h after irradiation. IL-1β and TGF-β were measured using sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, mouse IL-1β ELISA MAX™ Standard Set; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and human/mouse TGF beta 1 ELISA ready-Set-Go! (second-generation; eBioscience). The ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions and each sample was measured in triplicate. The cytokines were quantified with an ELISA reader (HTS 700 Bio Assay Reader; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 450 nm using the HTSoft version 2·0 program. The supernatants generated during the phagocytosis assays were analysed in the same manner.

Immunoblotting

Western blot was used to analyse intracellular cell signalling molecules in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts 24 h after irradiation. pMΦ were isolated and washed with PBS, resuspended in lysis buffer A [10 mM HEPES pH 7·9, 10 mM KCl, 0·1 mM EDTA pH 8·0 supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA; 1 mM Vanadate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM NaF, 0·1 M phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF)] and incubated for 10 min. Consecutively, 10 μl of 1% non-ionic, non-denaturating detergent IGEPAL CA-630 were added and incubated for 1 min. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (850 g, 4 min, 4°C) and supernatants including cytoplasmic extracts were isolated. The pellet was washed with lysis buffer A and centrifuged again (500 g, 3 min, 4°C). The subsequent isolation of nuclear extracts was performed through incubation of cell pellets with lysis buffer B (20 mM HEPES pH 7·9, 0·4 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce Biotechnology; 1 mM vanadate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM NaF, 0·1 M PMSF) for 45 min at 4°C and shaking. Supernatants containing nuclear extracts were isolated after centrifugation (18 000 g, 17 min, 4°C). Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Proteins were separated using 12% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After transfer, membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) in PBS-T (PBS supplemented with 0·05% Tween20) solution for 30 min and incubation with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were p38, p-p38, p-JNK, JNK (1:200; all Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA), NF-кB p65 (1:500; Biolegend), ERK and p-ERK (1:2000; all Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Subsequently, membranes were washed with PBS-T and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies, goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig)G (both Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) or donkey anti-goat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After another washing step, the membranes were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method. The luminescence was visualized using Amersham Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare Limited, Munich, Germany) and the film processor Curix 60 (Agfa, Leverkusen, Germany). Furthermore, densitometric analysis of the Western blots was performed using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Peritoneal macrophages of at least eight individual mice were used for cytokine analyses and at least three for functional/cell death experiments. Further, the results of at least three mice are shown for chemotaxis and transmigration experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Student's t-tests. Additionally, normal distribution was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Results were considered statistically significant for P < 0·05 (*) and highly significant for P < 0·01 (#).

Results

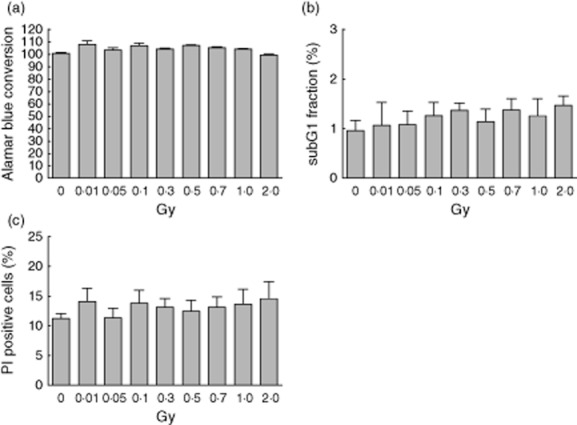

X-irradiation up to 2 Gy does not impact upon viability of activated macrophages

Alamar Blue conversion measurements revealed no significant influence of X-irradiation on the overall viability of pMΦ (Fig. 2a). In accordance, apoptotic cell death was not induced by X-irradiation, as no significant alteration of the subG1-DNA content was detectable (Fig. 2b). Further, the amount of PI-positive pMΦ representing necrotic cells was not altered significantly after exposure up to a single dose of 2 Gy (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Viability and cell death of activated peritoneal macrophages after exposure to low, moderate or high dose of X-irradiation. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated peritoneal mouse macrophages of BALB/c mice were irradiated with the indicated doses and consecutively cultured for 24 h. Viability was measured by Alamar Blue conversion assay (a). The subG1 DNA content as marker for apoptosis (b) and the rupture of the integrity of the plasma membrane as marker for necrosis (c) was assessed by propidium-iodide (PI) staining in the presence (b) or absence (c) of detergent and measured by flow cytometry. Means of three independent experiments (each measured in triplicate) and standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) are displayed.

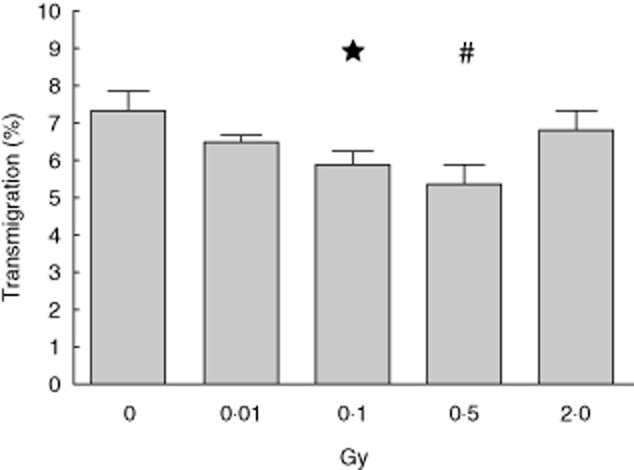

Transmigration of activated macrophages is reduced after exposure to 0·1 or 0·5 Gy of X-ray

The transmigration rate of pMΦ towards the FPR agonist WKYMVm (200 ng/ml) was reduced significantly at a single low dose of 0·1 Gy and a single moderate dose of 0·5 Gy (Fig. 3). A discontinuous dose dependency exists, as after exposure to 2 Gy similar transmigration was observed as after 0·01 Gy.

Fig. 3.

Transmigration of activated peritoneal macrophages after exposure to low, moderate or high dose of X-irradiation. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated peritoneal mouse macrophages of BALB/c mice were irradiated with the indicated doses and cultured consecutively for 24 h. Afterwards, transmigration through 5 μm pore-sized filter plates towards formyl peptide receptor (FPR) agonist WKYMVm (200 ng/ml) was determined. The mean of two representative experiments each performed in hexaplicate is shown and error bars display standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). *P < 0·05, #P < 0·01; calculated with the unpaired Student's t-test against mock-treated peritoneal macrophages (0 Gy).

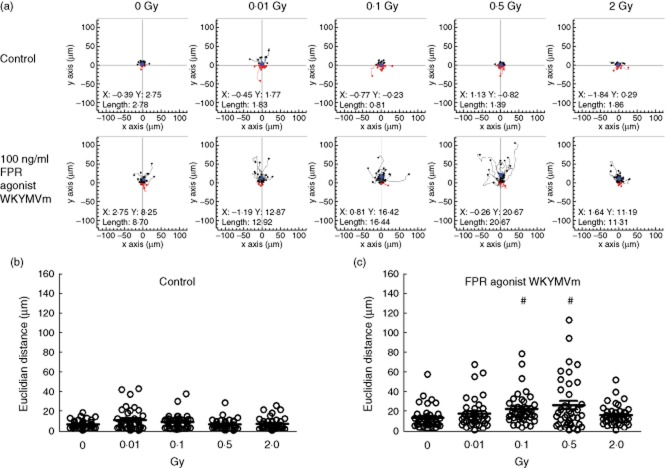

Chemotaxis of LPS-activated macrophages is enhanced after exposure to 0·1 or 0·5 Gy of X-ray

In contrast to the transmigration, a significant increase in the euclidian distance (Fig. 4), also called linear distance, representing the chemotactic movement of the pMΦ, was detected after exposure to a single dose of 0·1 or 0·5 Gy. A discontinuous dose dependency was again detected with a maximum of chemotaxis after exposure to 0·5 Gy of X-ray (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Chemotaxis of activated peritoneal macrophages after exposure to low, moderate or high dose of X-irradiation. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated peritoneal mouse macrophages of BALB/c mice were irradiated with the indicated doses and cultured consecutively for 24 h. Afterwards, live cell tracking in IBIDI 2D chemotaxis μ-slides with the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) agonist WKYMVm (100 ng/ml) was performed. LPS-activated peritoneal mouse macrophages subjected to culture medium only served as control. Migration of 40 randomly selected cells was tracked, and the resulting trajectory paths are shown in (a). Black paths depict cells with net migration towards the gradient; red paths depict cells with net migration against it. The filled blue circles represent the centres of mass, and the coordinates are given in the plots. Euclidian distance (linear distance between start and end position) was calculated from the trajectory paths (b,c). Dots represent values of individual cells and bars indicate the mean. #P < 0·01; calculated with the unpaired Student's t-test against mock-treated peritoneal macrophages (0 Gy).

X-irradiation is without impact on the phagocytic function of activated macrophages

As expected, differences in the percentage of phagocytosis were present in dependence of the amount of apoptotic and necrotic cells in the target. Mock-treated CT-26 cells with the lowest percentage of dead cells (apoptosis 1%; necrosis 6%) were taken up by approximately 10% of the pMΦ, while doxorubicin-treated cells with the highest percentage of dead cells (apoptosis 40%; necrosis 43%) were taken up best (phagocytosis of approximately 40%; Fig. 5b). In all cases, irradiation with a single dose of X-ray up to 2 Gy did not impact upon the percentage of phagocytosis (Fig. 5c–e). Analyses of cytokines revealed no significant alterations during phagocytosis (data not shown).

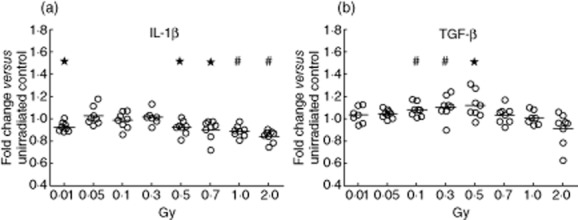

X-irradiation modulates inflammatory cytokine secretion of activated macrophages

As shown previously by our group, X-irradiation with 0·5 or 0·7 Gy induces a reduced secretion of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β by mouse and human macrophages that have been co-activated with LPS and MSU [21,22]. We were now interested in how the secretion of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines is altered in pMΦ that have been single-activated with LPS. The basal levels (LPS-treated unirradiated macrophages) of secreted IL-1β were ∼500pg/ml and those of TGF-β ∼800 pg/ml. Again, 0·5 or 0·7 Gy of X-ray induced a significantly reduced secretion of IL-1β, and also higher single doses (1·0 or 2·0 Gy) resulted in significantly reduced secretion of this inflammatory cytokine 24 h post-irradiation compared to unirradiated controls (Fig. 6a). Additionally, even a very low dose of 0·01 Gy was capable of significantly reducing the secretion of IL-1β, again demonstrating discontinuous dose dependencies after exposure of activated macrophages to X-ray. The TNF-α secretion, another prominent proinflammatory cytokine, showed higher variability between the single experiments. Only a higher single dose of 1·0 or 2·0 Gy led to a significantly reduced secretion of this inflammatory cytokine by pMΦ (data not shown). In contrast, the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β was enhanced significantly after exposure of pMΦ to 0·1, 0·3 or 0·5 Gy of X-ray (Fig. 6b). Of note is that, in concordance with previous work dealing with immune modulation by LD-RT (summarized in [38]), the single moderate dose of 0·5 Gy again resulted in the most anti-inflammatory microenvironment (reduced IL-1β and concomitantly enhanced TGF-β).

Fig. 6.

Cytokine secretion of activated peritoneal macrophages after exposure to low, moderate, or high dose of X-irradiation. The fold change of the concentration of interleukin (IL)-1β (a) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (b) in the supernatants of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated peritoneal mouse macrophages of BALB/c mice that were irradiated with the indicated doses referring to the mock-treated control (0 Gy) after 24 h of incubation is shown. Measurements were performed in triplicates using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Dots represent single values of macrophages from individual mice and bars the mean value of all mice (n = 8). *P < 0·05, #P < 0·01; calculated with the unpaired Student's test against the standardized value (set to 1) of mock treated peritoneal macrophages (0 Gy).

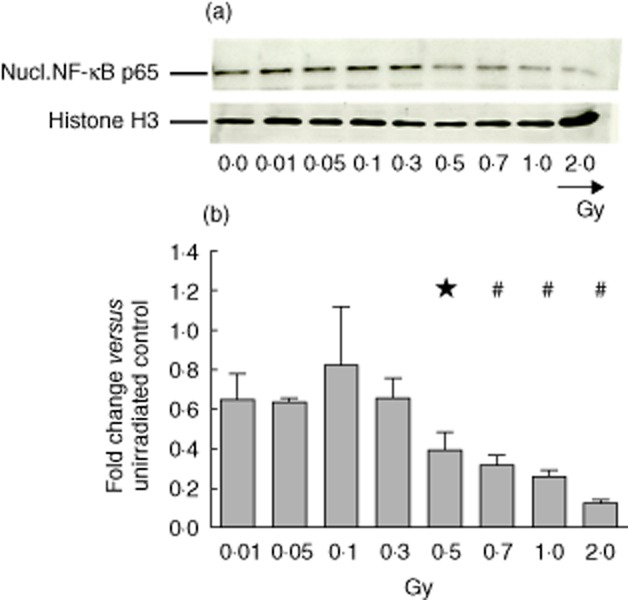

Starting from 0·5 Gy, X-irradiation reduces nuclear translocation of p65 in activated macrophages

MAPK p38 and NF-кB p65 are key regulator molecules of the transcription of inflammatory cytokines. Previous experiments revealed that low/moderate doses of X-irradiation may reduce inflammation by having an impact upon p38 and/or NF-кB [22,39–41]. Analyses of cytosolic MAPK (ERK, p38 and JNK) and their corresponding phosphorylated forms showed no significant alterations after exposure of LPS-activated pMΦ to single doses of X-ray up to 2·0 Gy (data not shown). In contrast, the amount of nuclear NF-кB p65 was significantly reduced, starting at a single dose of 0·5 Gy and up to 2·0 Gy (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Content of nuclear factor (NF)-кB p65 of activated peritoneal macrophages after exposure to low, moderate or high dose of X-irradiation. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated peritoneal mouse macrophages of BALB/c mice were irradiated with the indicated doses and cultured consecutively for 24 h. Afterwards, nuclear cell extracts were generated and analysed using the Western blot technique. In each lane the same protein amount was loaded and Histone H3 served as loading control. Western blot of one representative experiment out of three is shown in (a). Further, in (b) a densitometric analysis of the Western blots performed using ImageJ software is displayed. In order to visualize the altered protein amount, the protein level of mock-treated (0 Gy) macrophages was set to 1 and all other levels were referred to it. The mean of three independent experiments is displayed and error bars show standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). *P < 0·05, #P < 0·01; calculated with the paired Student's t-test against the standardized value (set to 1) of mock treated peritoneal macrophages (0 Gy).

Discussion

Macrophages are a crucial component of the innate immune system and, as professional phagocytes, are key players in the initiation and resolution of inflammation. Therefore, their viability and phagocytic power are of special importance for the body's homeostasis. How irradiation impacts upon this is scarcely known, and in times of increasing exposure to environmental and medically applied irradiation, this is becoming increasingly important. Our cell death and functional studies with LPS-activated pMΦ, mimicking macrophages in an inflamed environment, showed no alterations up to a single dose of 2 Gy. Kaina et al. also reported that the viability of human monocyte-derived macrophages, in contrast to monocytes themselves, is not altered even up to a single dose of X-ray of 5 Gy [18]. We conclude that macrophages in a non-inflamed and inflamed environment are radioresistant. The question then arose whether they can still fulfil their phagocytic functions. In the macrophage RAW 264·7 cell line, no significant changes in phagocytosis of latex beads was observed in the low-dose as well as the high-dose range when irradiation was performed with X-rays [19]. This was independent of the activation status of the macrophages. Our results also confirm that phagocytosis of a cell target is not altered significantly after exposure of activated macrophages to X-ray up to 2 Gy. The percentage of phagocytosis of pMΦ was dependent upon the composition of the target, but not influenced by exposure of the innate immune cells to X-ray. These results indicate that macrophages which are, for example, associated with a tumour are capable of maintaining viability and function up to a clinically relevant single dose of 2 Gy applied in classical RT of solid tumours. Furthermore, with regard to radiation protection issues, the maintained functional competence of macrophages after exposure to irradiation is reassuring, as invading pathogens or damaged cells can still be cleared properly. To avoid autoimmune reactions in the body, the latter is of great importance [42].

Before monocytes/macrophages can properly clear infected, damaged and/or dying cells, they have to find the target [43]. We were therefore interested whether and how the migration and chemotactic behaviour of activated macrophages is influenced by irradiation. In vivo, monocytes are recruited to the inflamed site and must traverse barriers to reach it. There, they differentiate into macrophages that will then become activated. Macrophages are located within tissues and do not greatly migrate. We also observed low basal transmigration rates of activated macrophages (around 7%) in our ex-vivo model system. None the less, a reduced transmigration of the activated macrophages after exposure to low and moderate single doses of 0·1 and 0·5 Gy was observed, respectively. Movement through the filter might mimic barriers within tissues. We conclude that irradiation slightly reduces the migration of activated macrophages within inflamed sites. Whether this impacts upon attenuation of inflammation has yet to be proved in future experiments. Fewer (inflammatory) macrophages can be related to a reduced or no further accelerated inflammation [38]. Investigations performed with monocytes revealed reduced evasion from the blood into inflamed tissue after moderate X-irradiation, which was mediated by decreased chemokine secretion and reduced expression of adhesion molecules such as P-, L- and E-selectins [10–12]. In future, these findings could provide clues concerning the underlying mechanisms in macrophages, as they differentiate from monocytes and thereby share some common features [44].

In contrast to transmigration, chemotactic analyses using the IBIDI μ-slides system revealed a significantly increased euclidian distance of pMΦ after exposure to X-ray of 0·1 or 0·5 Gy. While in the transmigration assay a burden in terms of the filter membrane is present, the pMΦ can move without having to pass a restriction in the chemotaxis assay. One might speculate that these macrophages, which are already at a site of inflammation in tissues with low barriers, are more capable of a chemotactic movement after X-irradiation with low or moderate doses. The more effective movement of macrophages towards an inflammatory stimulus such as formyl peptide receptor (fMLP) could further result in faster resolution of the inflammation, which could explain the beneficial clinical effects of attenuating inflammation. We chose the peritoneal macrophage system with LPS activation to generate macrophages displaying a defined inflammatory status quickly and reliably. However, there is no doubt that activated peritoneal macrophages cannot be a model for every macrophage type. The phenotype of activated macrophages in vivo certainly depends strongly upon the tissue localization. It has become evident that tissue niche-specific factors dictate the phenotype of macrophages [45].

Besides the movement towards an inflamed site to regulate inflammation and phagocytosis to maintain homeostasis, macrophages influence their micromilieu by the secretion of cytokines and thereby also control inflammation [46]. The cytokine secretion analyses revealed a decrease in the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β and an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine TGF-β, especially after irradiation with moderate doses. This can be equalized with a change to a more anti-inflammatory phenotype of the LPS-activated pMΦ. Even if a significant reduction of IL-1β and significant increase of TGF-β are observed after exposure to 0·5 Gy of X-ray, the actual variation is small. This suggests that, besides a slight modulation of the inflammatory cytokine milieu, distinct further pathways have to be affected by low-dose radiation exposure to finally attenuate inflammation. The attenuation of inflammation by LD-RT is definitely not linked to modulation of the inflammatory phenotype of only macrophages. Granulocytes, lymphocytes and endothelial cells have also been proved to be involved (summarized in [47]).

Activation of TGF-β is an early and persistent event in irradiated tissues and induces immune suppression [48]. Our findings fit with other studies demonstrating a maximal anti-inflammatory effect of X-irradiation at a single dose of 0·5 Gy [10–12,21,22]. For IL-1β and TNF-α we also saw a significant decrease after irradiation with a high single dose of 2·0 Gy compared to the mock-treated control, which is in contrast to findings observed in mouse and human model systems with co-activated macrophages [21,22]. Of note is that we even detected IL-1β in the supernatant of pMΦ which were activated with one stimulus, namely LPS, only. The transcription and secretion of this inflammatory cytokine has been described as a multi-step pathway that requires two stimuli for the secretion of active IL-1β. In a first step the transcription of the pro-form of IL-1β (p35) is activated by NF-кB upon the activation of Toll-like receptors by various stimuli such as LPS. Transcription is followed by the cleavage of the pro-form through active caspase-1 into the active form (p17) (summarized in [49]). Particularly for the activation of the inflammasome leading to active caspase-1, a second stimulus such as MSU is required [50]. Nevertheless, the LPS-activated pMΦ that we used as the model system are capable of secreting active IL-1β. The first stimulus might come from the Brewer's thioglycollate to recruit the macrophages into the peritoneum. Further, Turchyn et al. showed that LPS-activated peritoneal macrophages, induced by casein, are capable of secreting active IL-1β without a ‘second’ adenosine triphosphate stimulus [51].

Cell signalling molecules such as NF-кB p65, ERK or p38 are known to be involved in inflammatory cytokine transcription [39–41]. The latter two were not altered after low-/moderate-/high-dose X-irradiation of activated pMΦ, whereas a significantly decreased nuclear amount of NF-кB p65, starting at a single dose of 0·5 up to 2·0 Gy, was observed. The extracellular amount of IL-1β was also reduced at a single dose of 0·5 up to 2·0 Gy. However, the reduction of p65 in the nucleus was much more pronounced than the observed reduced secretion of IL-1β. Because NF-kB regulates a manifold of genes involved in inflammation, activation of immune cells, apoptosis, survival and proliferation, we conclude that as well as the reduction of IL-1β, several other pathways are affected by radiation exposure or during the response to radiation. While we also observed a significant reduction of TNF-α after exposure of 1·0 or 2·0 Gy of X-ray, no significant alterations were observed at lower doses. This suggests that other transcription factors than NF-кB are involved in regulating TNF-α in activated macrophages after exposure to LD-RT. The same applies for the reduced secretion of IL-1β after exposure of activated macrophages to 0·01 Gy, as no significant reduction of p65 was present in the nucleus. In human co-activated THP-1 macrophages, the reduced nuclear amount of NF-кB p65 also correlated with decreased secretion of IL-1β [22]. In co-activated human macrophages, p38 is also slightly reduced after 0·5 or 0·7 Gy of X-ray [22]. Further, the basal inflammatory status of the macrophages also impacts upon cytokine modulation by ionizing radiation. It has become evident that immune responses are initiated or affected by ionizing radiation [47].

To summarize, the data from this study further support that an intermediate dose of 0·5 Gy of X-irradiation might contribute to the reduction of pain in patients with benign degenerative and inflammatory diseases by down-regulation of inflammation: reduced transmigration of activated macrophages, increased chemotaxis towards an inflamed site and the creation of a more anti-inflammatory microenvironment was observed. Future research will also focus upon how the immune status in the peripheral blood of LD-RT patients changes during and after therapy [7]. Further, with regard to radiation protection issues, the data demonstrate that the viability and phagocytic function of activated macrophages is not influenced by ionizing radiation up to a single dose of 2·0 Gy.

The change in the inflammatory phenotype of LPS-activated pMΦ after exposure to ionizing radiation could also have implications for cancer biology. Inflammation is regarded as a double-edged sword in view of an emerging cancer disease. On the one hand, the tumour cells try to reduce acute inflammation to avoid destruction by infiltrating immune cells, the so-called evasion [26]. On the other hand, chronic inflammation is in favour of tumours as invasion and angiogenesis are fostered [52,53]. Recently, Klug et al. described that irradiation of tumours with 2 Gy programmes macrophages to a M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective CD8+ T cell immune therapy [54]. They demonstrated that the tumour vasculature becomes normalized and that the ionizing radiation induces secretion of iNOS by the macrophages. This fosters the recruitment of CD8+ T cells that are capable of killing the tumour cells, suggesting that a single dose of X-ray of 2 Gy is capable of modulating the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages.

We have demonstrated that single low, moderate and even high doses of X-ray are capable of inducing a more anti-inflammatory phenotype of already activated macrophages. A reduction of inflammation can be beneficial for suppression angiogenesis and evasion of the tumour, but might also result in reduced immune reactions against the tumour. In emerging early tumours, inflammatory pMΦ are predominantly present [27,28]. It might be speculated that in early tumour stages X-ray exerts its beneficial effects in part by changing the macrophage's phenotype to a more anti-inflammatory one. It is becoming increasingly evident that DNA damage responses are connected to inflammatory events [55]. Our results support that several distinct pathways are affected either by radiation exposure or during the response to radiation. Future research should focus upon how the fine-tuning of inflammation is regulated by distinct low, moderate and high doses of X-ray and how this depends upon a pre-existing inflammatory status. One thing has become clear: inflammation is modulated in part by LD-X-irradiation via changing the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Commissions (DoReMi, European Network of Excellence, contract number 249689), by the German Research Foundation (GA 1507/1-1 and SFB914), and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (GREWIS, 02NUK017G).

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unanue ER, Beller DI, Calderon J, Kiely JM, Stadecker MJ. Regulation of immunity and inflammation by mediators from macrophages. Am J Pathol. 1976;85:465–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glatzel M, Frohlich D, Basecke S, Krauss A. Analgesic radiotherapy for osteoarthrosis of digital joints and rhizarthrosis Radiotherapy and. Oncology. 2004;71:S24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keilholz L, Seegenschmiedt H, Sauer R. [Radiotherapy for painful degenerative joint disorders. Indications, technique and clinical results] Strahlenther Onkol. 1998;174:243–250. doi: 10.1007/BF03038716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruppert R, Seegenschmiedt MH, Sauer R. [Radiotherapy of osteoarthritis. Indication, technique and clinical results] Orthopade. 2004;33:56–62. doi: 10.1007/s00132-003-0568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott OJ, Hertel S, Gaipl US, Frey B, Schmidt M, Fietkau R. Benign painful shoulder syndrome: initial results of a single-center prospective randomized radiotherapy dose-optimization trial. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012;188:1108–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott OJ, Hertel S, Gaipl US, Frey B, Schmidt M, Fietkau R. The Erlangen Dose Optimization trial for low-dose radiotherapy of benign painful elbow syndrome: long-term results. Strahlenther Onkol. 2014;190:394–398. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0504-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ott OJ, Jeremias C, Gaipl US, Frey B, Schmidt M, Fietkau R. Radiotherapy for achillodynia : results of a single-center prospective randomized dose-optimization trial. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189:142–146. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ott OJ, Jeremias C, Gaipl US, Frey B, Schmidt M, Fietkau R. Radiotherapy for calcaneodynia. Results of a single center prospective randomized dose optimization trial. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kern PM, Keilholz L, Forster C, Hallmann R, Herrmann M, Seegenschmiedt MH. Low-dose radiotherapy selectively reduces adhesion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to endothelium in vitro. Radiother Oncol. 2000;54:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildebrandt G, Maggiorella L, Rodel F, Rodel V, Willis D, Trott KR. Mononuclear cell adhesion and cell adhesion molecule liberation after X-irradiation of activated endothelial cells in vitro. Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:315–325. doi: 10.1080/09553000110106027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodel F, Hofmann D, Auer J, et al. The anti-inflammatory effect of low-dose radiation therapy involves a diminished CCL20 chemokine expression and granulocyte/endothelial cell adhesion. Strahlenther Onkol. 2008;184:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00066-008-1776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodel F, Frey B, Gaipl U, et al. Modulation of inflammatory immune reactions by low-dose ionizing radiation: molecular mechanisms and clinical application. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:1741–1750. doi: 10.2174/092986712800099866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kern P, Keilholz L, Forster C, Seegenschmiedt MH, Sauer R, Herrmann M. In vitro apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells induced by low-dose radiotherapy displays a discontinuous dose-dependence. Int J Radiat Biol. 1999;75:995–1003. doi: 10.1080/095530099139755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hildebrandt G, Loppnow G, Jahns J, et al. Inhibition of the iNOS pathway in inflammatory macrophages by low-dose X-irradiation in vitro. Is there a time dependence? Strahlenther Onkol. 2003;179:158–166. doi: 10.1007/s00066-003-1044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hildebrandt G, Radlingmayr A, Rosenthal S, et al. Low-dose radiotherapy (LD-RT) and the modulation of iNOS expression in adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:993–1001. doi: 10.1080/09553000310001636639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer M, Goldstein M, Christmann M, Becker H, Heylmann D, Kaina B. Human monocytes are severely impaired in base and DNA double-strand break repair that renders them vulnerable to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21105–21110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111919109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conrad S, Ritter S, Fournier C, Nixdorff K. Differential effects of irradiation with carbon ions and X-rays on macrophage function. J Radiat Res. 2009;50:223–231. doi: 10.1269/jrr.08115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsukimoto M, Homma T, Mutou Y, Kojima S. 0.5 Gy gamma radiation suppresses production of TNF-alpha through up-regulation of MKP-1 in mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells. Radiat Res. 2009;171:219–224. doi: 10.1667/RR1351.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frischholz B, Wunderlich R, Ruhle PF, et al. Reduced secretion of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1beta by stimulated peritoneal macrophages of radiosensitive Balb/c mice after exposure to 0.5 or 0.7Gy of ionizing radiation. Autoimmunity. 2013;46:323–328. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2012.747522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lodermann B, Wunderlich R, Frey S, et al. Low dose ionising radiation leads to a NF-kappaB dependent decreased secretion of active IL-1beta by activated macrophages with a discontinuous dose-dependency. Int J Radiat Biol. 2012;88:727–734. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2012.689464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zumsteg A, Christofori G. Corrupt policemen: inflammatory cells promote tumor angiogenesis. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:60–70. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32831bed7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solinas G, Schiarea S, Liguori M, et al. Tumor-conditioned macrophages secrete migration-stimulating factor: a new marker for M2-polarization, influencing tumor cell motility. J Immunol. 2010;185:642–652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagemann T, Wilson J, Burke F, et al. Ovarian cancer cells polarize macrophages toward a tumor-associated phenotype. J Immunol. 2006;176:5023–5032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, et al. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 2011;167:e211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:287–296. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schleicher U, Bogdan C. Generation, culture and flow-cytometric characterization of primary mouse macrophages. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;531:203–224. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-396-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riccardi C, Nicoletti I. Analysis of apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1458–1461. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peter C, Waibel M, Keppeler H, et al. Release of lysophospholipid ‘find-me’ signals during apoptosis requires the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1. Autoimmunity. 2012;45:568–573. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2012.719947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blume KE, Soeroes S, Keppeler H, et al. Cleavage of annexin A1 by ADAM10 during secondary necrosis generates a monocytic ‘find-me’ signal. J Immunol. 2012;188:135–145. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodel F, Frey B, Manda K, et al. Immunomodulatory properties and molecular effects in inflammatory diseases of low-dose X-irradiation. Front Oncol. 2012;2:120. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter AB, Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. Both Erk and p38 kinases are necessary for cytokine gene transcription. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:751–758. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collart MA, Baeuerle P, Vassalli P. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha transcription in macrophages: involvement of four kappa B-like motifs and of constitutive and inducible forms of NF-kappa B. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1498–1506. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiscott J, Marois J, Garoufalis J, et al. Characterization of a functional NF-kappa B site in the human interleukin 1 beta promoter: evidence for a positive autoregulatory loop. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6231–6240. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaipl US, Sheriff A, Franz S, et al. Inefficient clearance of dying cells and autoreactivity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;305:161–176. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29714-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lauber K, Ernst A, Orth M, Herrmann M, Belka C. Dying cell clearance and its impact on the outcome of tumor radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2012;2:116. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mildner A, Yona S, Jung S. A close encounter of the third kind: monocyte-derived cells. Adv Immunol. 2013;120:69–103. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:986–995. doi: 10.1038/ni.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ortega-Gomez A, Perretti M, Soehnlein O. Resolution of inflammation: an integrated view. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:661–674. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodel F, Frey B, Multhoff G, Gaipl U. Contribution of the immune system to bystander and non-targeted effects of ionizing radiation. Cancer Lett. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.015. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du S, Barcellos-Hoff MH. Tumors as organs: biologically augmenting radiation therapy by inhibiting transforming growth factor beta activity in carcinomas. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2013;23:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tschopp J, Martinon F, Burns K. NALPs: a novel protein family involved in inflammation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:95–104. doi: 10.1038/nrm1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinon F, Gaide O, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tschopp J. NALP inflammasomes: a central role in innate immunity. Semin Immunopathol. 2007;29:213–229. doi: 10.1007/s00281-007-0079-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turchyn LR, Baginski TJ, Renkiewicz RR, Lesch CA, Mobley JL. Phenotypic and functional analysis of murine resident and induced peritoneal macrophages. Comp Med. 2007;57:574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeNardo DG, Andreu P, Coussens LM. Interactions between lymphocytes and myeloid cells regulate pro- versus anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:309–316. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, et al. Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS(+)/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:589–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Figueiredo N, Chora A, Raquel H, et al. Anthracyclines induce DNA damage response-mediated protection against severe sepsis. Immunity. 2013;39:874–884. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]