Abstract

Background

Prior study demonstrated that baseline Sinonasal Outcomes Test-22 (SNOT-22) aggregate scores accurately predict selection of surgical intervention in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). Factor analysis of the SNOT-22 survey has identified 5 distinct domains that are differentially impacted by endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). This study sought to quantify SNOT-22 domains in patient cohorts electing both surgical or medical management and post-interventional change in these domains.

Methods

Patients CRS were prospectively enrolled into a multi-institutional, observational cohort study. Subjects elected continued medical management or ESS. SNOT-22 domain scores at baseline were compared between treatment cohorts. Post-intervention domain score changes were evaluated in subjects with at least 6-month follow-up.

Results

363 subjects were enrolled with 72(19.8%) electing continued medical management while 291(80.2%) elected ESS. Baseline SNOT-22 domain scores were comparable between treatment cohorts in sinus-specific domains (Rhinologic, Extra-nasal rhinologic, and Ear/facial symptoms, p>0.050); however, the surgical cohort reported significantly higher psychological (16.0(8.4)vs.12.0(7.1); p<0.001) and sleep dysfunction (13.7(6.8)vs.10.5(6.2); p<0.001) than the medical cohort. Effect sizes for ESS varied across domains with Rhinologic and Extra-nasal rhinologic symptoms experiencing the greatest gains (1.067 and 0.997, respectively) while Psychological and Sleep dysfunction experiencing the smallest improvements (0.805 and 0.818, respectively). Patients experienced greater mean improvements after ESS in all domains compared to the medical management (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Subjects electing ESS report higher sleep and psychological dysfunction compared to medical management but have comparable sinus-specific symptoms. Subjects undergoing ESS experience greater gains than medical management across all domains; however these gains are smallest in the psychological and sleep domains.

MeSH Key Words: sinusitis, therapeutics, quality of life, outcome assessment, endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a very common disease that can be managed either medically or surgically with ongoing medical management. Multi-institutional cohort data has demonstrated that patients improve on the disease-specific quality-of-life (QOL) scores to a greater degree with surgical intervention than with medical management.1 Investigation as to why some patients elect continued medical therapy over surgery identified baseline aggregate sinonasal outcome test (SNOT-22) score as a significant predictor of selecting endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). There is a direct relationship between worse baseline SNOT-22 score and a higher probability of electing ESS.2 Metrics of baseline symptom severity appear more effective at predicting treatment modality selection than a variety of other measures including: personality traits, risk aversion, degree of social support, economic factors and the patient-physician relationship.

Factor analyses of both the SNOT-20 and SNOT-22 instruments have demonstrated that these surveys actually measure more than one single disease-specific or health-related construct.3–5 The individual SNOT-20 survey items can be categorized into four different domains, which are differentially impacted by CRS subtypes in both surgical3 and nonsurgical populations.4 Similarly, the SNOT-22 measures five different underlying domains that are each impacted uniquely by surgical therapy.5 In the case of the SNOT-22, the domains breakdown into 3 sinus-specific symptom domains (Rhinologic, Extra-rhinologic and Ear/facial symptoms) and 2 general health-related QOL domains (Psychological and Sleep dysfunction). Just as the domains underlying the SNOT-22 respond differently to given treatment modalities or disease subtypes they may each uniquely motivate patients to elect a given treatment modality. Domains associated with selection of a given treatment modality may not necessarily in turn, however, respond to that elected treatment modality.

The goals of the present study were to investigate which of the discrete domains of the SNOT-22 best predict treatment modality selection, as well as describe and compare changes in domain scores after either continued medical management or surgical intervention for symptoms of CRS.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Patient Population and Inclusion Criteria

Adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) with a current diagnosis of medically refractory CRS were prospectively enrolled into an ongoing, multi-institutional, observational, cohort study to compare the effectiveness of treatment outcomes for this chronic disease process. Preliminary findings from this cohort have been previously described.2,6–9 The diagnosis of CRS was defined by the 2007 Adult Sinusitis Guideline,10 with prior treatment with oral, broad spectrum, or culture directed antibiotics (≥ 2 weeks duration) and either topical nasal corticosteroid sprays (≥ 3 week duration) or a 5-day trial of systemic steroid therapy necessary for enrollment. Enrollment sites consisted of four academic, tertiary care rhinology practices as part of the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU, Portland, OR, USA), the Medical Univeristy of South Carolina (Charleston, SC, USA), Stanford University (Palo Alto, CA, USA), and the University of Calgary (Calgary, Alberta, Canada). The Institutional Review Board at each enrollment location provided oversight and annual review of the informed consent process and all investigational protocols, while central review and coordination services were conducted at OSHU (eIRB #7198).

Treatment modality selection was not randomized or assigned for study purposes at any time point. Participants either selected continued, non-standardized medical therapy for control of symptoms associated with CRS or subsequent ESS based on individual disease processes and intraoperative clinical judgement of the enrolling physician at each site. Participants were either primary or revision surgery cases in both treatment groups. Surgical procedures consisted of either unilateral or bilateral maxillary anstrostomy, partial or total ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy, frontal sinus procedures (Draf I, IIa/b, or III), with or without septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction.

Exclusion Criteria

Study participants diagnosed with a current exacerbation of recurrent acute sinusitis or ciliary dysfunction phenotype were excluded from the final study cohort due to the heterogeneity of those disease processes. Participants were also excluded from final analyses if they failed to complete all required baseline study evaluations or had not yet either entered into the minimum follow-up appointment time window or completed follow-up evaluations within 18 months after enrollment. Additional participants who originally selected to continue with medical management were excluded if they changed treatment modality (“crossed over”) during active follow-up.

Clinical Disease Severity Measures

During routine initial clinical / enrollment visits, all study subjects completed a medical history, head and neck clinical examinations, sinonasal endoscopy and computed tomography (CT) imaging of the coronal plane using 1.0–3.0mm axial slices, as part of the standard of care. Endoscopic examinations were scored using the Lund-Kennedy endoscopy scoring system where higher scores represent worse bilateral disease severity (score range: 0–20).11 Computed tomography images were evaluated and staged in accordance with the Lund-Mackay bilateral scoring system where higher scores represent higher bilateral severity of disease (score range: 0–24).12 Both CT imaging and endoscopy scores were assessed by the enrolling physician at each enrollment site.

Study Data Collection

Study participants were required to complete all necessary baseline surveys and informed consent in English. Consented participants were asked to provide demographic, social and medical history cofactors including, but not limited to: age, gender, race, ethnicity, asthma, nasal polyposis, known allergies (reported by patient history or confirmed skin prick or radioallergosorbent testing), acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) intolerance, depression, current tobacco use, history of prior sinus surgery, recurrent acute sinusitis, and ciliary dysfunction / cystic fibrosis.

Outcome Measurements

All study participants were asked to complete 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22) at baseline and at follow-up.13,14 The SNOT-22 is a validated, 22-item treatment outcome measure applicable to chronic sinonasal conditions (©2006, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA). Higher scores on the SNOT-22 survey items suggest worse patient functioning or symptom severity (total score range: 0–110). Scoring is conducted via Likert scale responses whereas 0=“No problem”, 1=“Very mild problem”, 2=“Mild or slight problem”, 3=“Moderate problem”, 4=“Severe problem”, and 5=“Problem as bad as it can be”. Participants were asked to complete the SNOT-22 survey at both baseline appointments and at least 6-months after continued medical therapy or ESS procedures when possible, with the assistance of a trained research coordinator at each site. Patients were lost to follow-up if they did not complete any survey evaluations within 18 months after enrollment. Physicians at each site were blinded to all patient-based survey responses for the study duration.

Individual domain scores of the SNOT-22 were operationalized following guidelines that have been previously described.5 The 22-items of the SNOT-22 survey were re-categorized and summarized into five distinct domains including: Rhinologic symptoms, Extra-nasal rhinologic symptoms, Ear / facial symptoms, Psychological dysfunction, and Sleep dysfunction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Categorized survey items for separate domains of the SNOT-22 instrument

| SNOT-22 Domains: | Survey Items: | Score Range: |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinologic Symptoms | #1, #2, #3, #6, #21, #22 | 0–30 |

| Extra-Nasal Rhinologic Symptoms | #4, #5, #6 | 0–15 |

| Ear/Facial Symptoms | #2, #7, #8, #9, #10 | 0–25 |

| Psychological Dysfunction | #14, #15, #16, #17, #18, #19, #20 | 0–35 |

| Sleep Dysfunction | #11, #12, #13, #14, #15 | 0–25 |

SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

De-identified SNOT-22 surveys were collected and transferred from each enrollment site to a central coordinating site (OHSU) using standardized clinical research forms. All study data was entered into a relational database (Microsoft Access, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and downloaded into a commercially available statistical software program (SPSS v.22, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Previously published literature utilizing this multi-center cohort of patients with CRS reported the prevalence of enrollment of patients electing medical management over ESS to be approximately a 1:3 ratio.2 Two-sided sample size estimations were determined using this ratio and based on detecting a range of mean change values on the SNOT-22 between treatment groups, assuming equal variance between treatment groups, 80% power (1-β error probability), and a conventional 0.050 alpha level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample size estimations for mean changes in SNOT-22 scores between treatment groups

| SNOT-22 Mean Score Difference: | Effect Size (d) | Treatment Group Ratio: | Total Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.110 | 1:3 | 3470 |

| 4 | 0.219 | 1:3 | 870 |

| 6 | 0.330 | 1:3 | 388 |

| 7 | 0.385 | 1:3 | 286 |

| 8 | 0.439 | 1:3 | 220 |

| 10 | 0.549 | 1:3 | 142 |

| 12 | 0.659 | 1:3 | 100 |

SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test

Descriptive analytics were utilized to evaluate demographic variables, medical comorbidities, baseline disease severity measures, and SNOT-22 domain scores for prevalence and assumptions of distribution normality where appropriate. Two-tailed independent sample t-tests were used to evaluate unadjusted mean differences between treatment modality cohort groups for all continuous variables. Chi-square (χ2) testing was used to compare the prevalence of demographic and comorbidity variables between treatment groups. Significant differences were determined using a standard 0.050 alpha level. The ability of each discrete domain to accurately predict treatment selection was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and resultant areas under the curve (AUC) determinations. Two-sided matched pair t-tests were used to assess changes in mean domain scores over time for both treatment groups. The percentage of relative improvement in SNOT-22 domain scores was calculated for each treatment group using the following formula: [(mean preoperative score – mean postoperative score)/mean preoperative score] x 100. Additionally, two-tailed standardized effect sizes were calculated post hoc between matched pair assuming a 0.050 error probability and associative between groups correlation coefficients for each separate domain.

RESULTS

Final Study Population

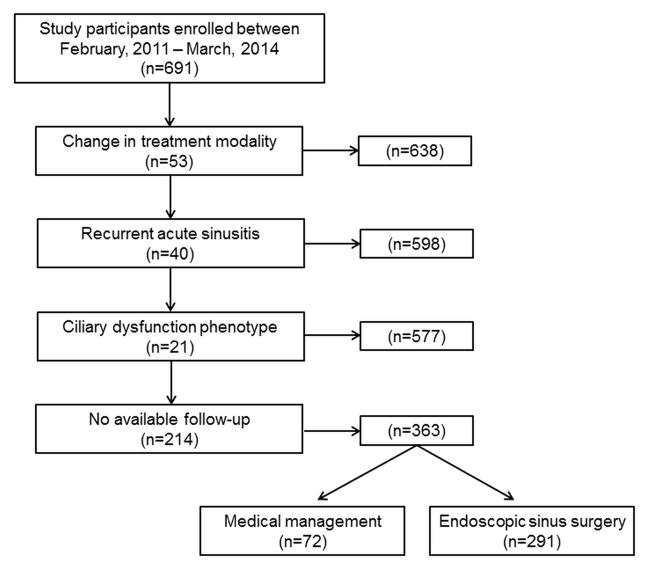

The application of inclusion and exclusion criteria allowed for a total of 363 participants with follow-up in the final analysis enrolled between February, 2011 and March, 2014 (Figure 1). A total of 72 (19.8%) participants elected continued medical management while 291 (80.1%) elected endoscopic sinus surgery as the subsequent treatment modality. Before exclusion criteria, both medical management and surgical treatment groups were found to have similar prevalence of follow-up (64.9% vs. 62.4%; p=0.635). Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and clinical disease severity measures were compared between treatment modality for participants with follow-up (Table 3). Patients electing ESS were found to have significantly worse baseline SNOT-22 aggregate scores.

Figure 1.

Final cohort selection after inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of subjects with follow-up by treatment modality

| Medical management (n=72) | Surgical treatment (n=291) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics: | Mean (SD) | N(%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | p-value |

| Follow-up (months) | (12.7) 5.8 | 13.5 (5.7) | 0.260 | ||

| Age (years) | 52.5 (14.1) | 52.6 (14.9) | 0.964 | ||

| Males | 29 (40.3) | 139 (47.8) | -- | ||

| Females | 43 (59.7) | 152 (52.2) | 0.254 | ||

| White / Caucasian | 61 (84.7) | 245 (84.2) | 0.912 | ||

| Hispanic / Latino | 1 (1.4) | 16 (5.5) | 0.213 | ||

| Medical comorbidity: | |||||

| Asthma | 24 (33.3) | 110 (37.8) | 0.482 | ||

| Nasal polyposis | 28 (38.9) | 113 (38.8) | 0.993 | ||

| Allergies (skin prick or mRAST) | 29 (40.3) | 110 (37.8) | 0.699 | ||

| ASA intolerance | 8 (11.1) | 26 (8.9) | 0.570 | ||

| Depression | 12 (16.7) | 49 (16.8) | 0.972 | ||

| Current tobacco smoker | 1 (1.4) | 18 (6.2) | 0.140 | ||

| Previous sinus surgery | 41 (56.9) | 153 (52.6) | 0.506 | ||

| Baseline disease severity: | |||||

| Computed tomography (CT) score | 13.2 (5.9) | 12.4 (6.1) | 0.355 | ||

| Endoscopy score | 6.7 (3.9) | 6.3 (3.8) | 0.523 | ||

| SNOT-22 score | 44.2 (18.2) | 53.4 (19.3) | <0.001 | ||

SD, standard deviation; mRAST, modified radioallergosorbent testing; SNOT-22, ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test.

Baseline SNOT-22 Domain Analysis

Baseline SNOT-22 scores stratified by domains identified rhinologic symptoms as the highest scoring domain in both cohorts but no difference between the two (Table 4). Patients from both cohorts also reported comparable scores in the extra-nasal rhinologic and ear/facial domains. Subjects electing surgical management reported significantly higher scores in the psychological dysfunction (p<0.001) and sleep dysfunction domains (p<0.001).

Table 4.

Baseline SNOT-22 domain scores by elected treatment modality

| Medical management (n=72) | Surgical treatment (n=291) | Unadjusted Mean Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 Domains: | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | B (SE) | t (df=360) | p-value |

| Rhinologic Symptoms | 15.2 (6.2) | 16.5 (6.1) | 1.3 (0.8) | −1.642 | 0.102 |

| Extra-Nasal Rhinologic Symptoms | 7.6 (3.2) | 8.5 (3.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | −1.903 | 0.058 |

| Ear/Facial Symptoms | 8.3 (5.4) | 9.3 (5.0) | 1.0 (0.7) | −1.474 | 0.141 |

| Psychological Dysfunction | 12.0 (7.1) | 16.0 (8.4) | 3.9 (1.1) | −3.656 | <0.001 |

| Sleep Dysfunction | 10.5 (6.2) | 13.7 (6.8) | 3.1 (0.9) | −3.569 | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; B, effect estimate; SE, standard error; t, t-test statistic; df, degrees of freedom; SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test.

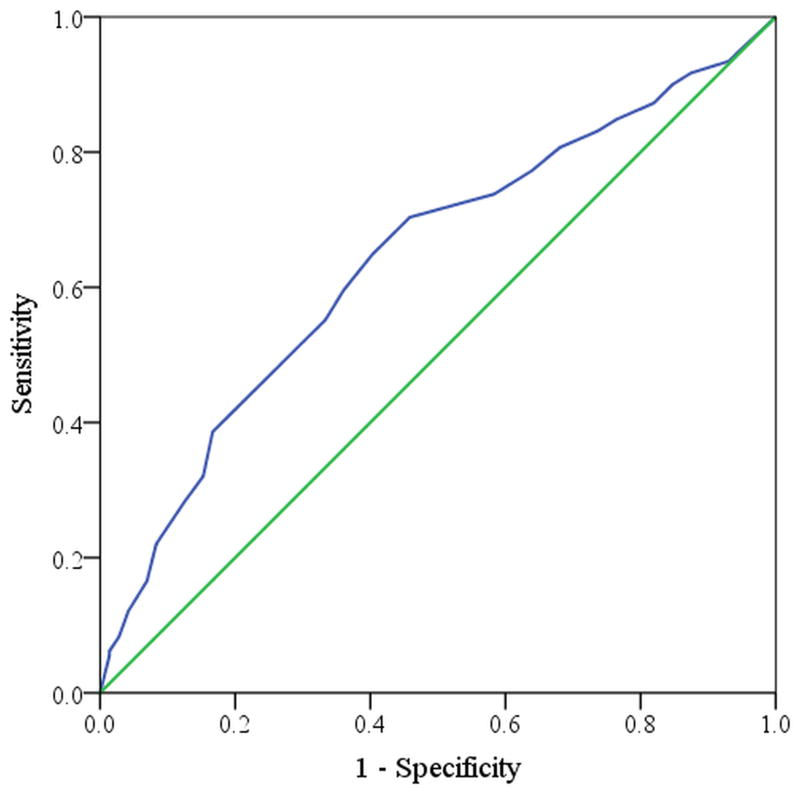

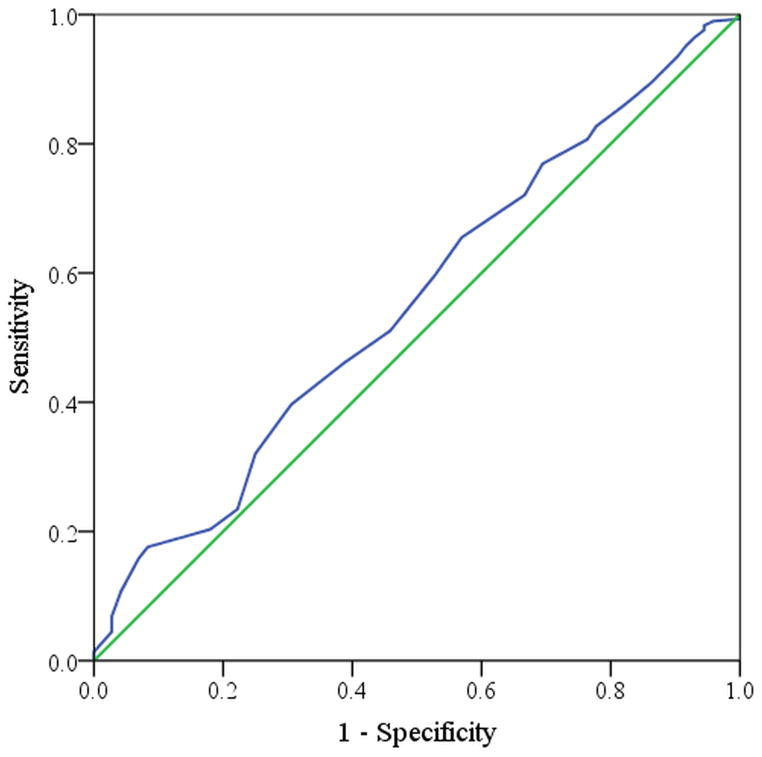

The ability of a given domain score to predict treatment modality can be represented in a receiver operating characteristic curve (Figure 2 and Figure 3) where the diagonal line represents a predictor that is no better than chance alone and a line that reaches the upper left hand corner of the space would be a flawless predictor or test. Baseline sleep dysfunction domain scores carried the greatest significant predictive probability of electing surgical therapy (Figure 2) in contrast to the rhinologic domain score, which was least predictive of electing surgical therapy (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curve for the sleep dysfunction symptom domain (AUC=0.641)

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curve for the rhinologic symptom domain (AUC=0.556)

Post-treatment interval change by domain score

Subjects significantly improved across all domains between baseline and follow-up time points in both treatment cohorts (Table 5). Rhinologic symptoms experienced the greatest absolute change in both the medical and surgical cohorts. The surgical cohort experienced greater improvement than the medical cohort across all domains (p<0.001) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Baseline and follow-up domain scores by treatment modality

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 Domains: | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | t (df=71) | p-value |

| Medical management: | ||||

| Rhinologic Symptoms | 15.2 (6.2) | 12.2 (6.5) | 3.453 | 0.002 |

| Extra-Nasal Rhinologic Symptoms | 7.6 (3.2) | 6.0 (3.2) | 3.577 | <0.001 |

| Ear/Facial Symptoms | 8.3 (5.4) | 6.8 (5.2) | 2.949 | 0.007 |

| Psychological Dysfunction | 12.0 (7.1) | 9.6 (8.4) | 2.701 | 0.009 |

| Sleep Dysfunction | 10.5 (6.2) | 9.0 (7.6) | 1.907 | 0.030 |

| Surgical treatment: | t (df=289) | |||

| Rhinologic Symptoms | 16.5 (6.1) | 8.4 (6.3) | 18.505 | <0.001 |

| Extra-Nasal Rhinologic Symptoms | 8.5 (3.4) | 4.6 (3.6) | 16.751 | <0.001 |

| Ear/Facial Symptoms | 9.3 (5.0) | 4.7 (4.7) | 15.737 | <0.001 |

| Psychological Dysfunction | 16.0 (8.4) | 9.0 (8.7) | 13.655 | <0.001 |

| Sleep Dysfunction | 13.7 (6.8) | 8.0 (6.9) | 13.907 | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; t, t-test statistic; df, degrees of freedom; SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test.

Table 6.

Absolute mean change of domain scores by treatment modality

| Medical management (n=72) | Surgical treatment (n=291) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 Domains: | Mean (SD) Change | Mean (SD) Change | ABS Δ (SE) | t | p-value |

| Rhinologic Symptoms | −3.0 (7.4) | −8.1 (7.4) | 5.1 (1.0) | 5.204 | <0.001 |

| Extra-Nasal Rhinologic Symptoms | −1.6 (3.8) | −3.8 (3.9) | 2.3 (0.5) | 4.397 | <0.001 |

| Ear/Facial Symptoms | −1.6 (4.6) | −4.6 (5.0) | 3.0 (0.7) | 4.679 | <0.001 |

| Psychological Dysfunction | −2.4 (7.6) | −6.9 (8.7) | 4.5 (1.1) | 4.063 | <0.001 |

| Sleep Dysfunction | −1.5 (6.7) | −5.7 (7.0) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.587 | <0.001 |

SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test; SD, standard deviation; ABS, absolute change; SE, standard error; t, t-test statistic.

Relative improvement was similar to findings of absolute change for both treatment cohorts, with the 3 sinus-specific symptom domains improving the greatest degree in the surgical intervention group, while the psychological and sleep domains were found to improve to a marginally lesser extent (Table 7). Relative improvement was represented as both a percentage of improvement from baseline as well as a standardized effect size, which is the mean change divided by the baseline sample standard deviation. Across all domains, participants in the surgical cohort reported experiencing greater relative improvement than reported by those subjects in the medical management cohort.

Table 7.

Measure of relative improvement in domain scores by treatment modality

| Medical management (n=72) | Surgical treatment (n=291) | Medical management (n=72) | Surgical treatment (n=291) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22 Domains: | Improvement (%) | Improvement (%) | Standardized Effect Size | Standardized Effect Size |

| Rhinologic Symptoms | 19.7% | 49.1% | 0.405 | 1.067 |

| Extra-Nasal Rhinologic Symptoms | 20.9% | 45.5% | 0.426 | 0.997 |

| Ear/Facial Symptoms | 19.1% | 49.8% | 0.322* | 0.920 |

| Psychological Dysfunction | 20.1% | 43.6% | 0.309* | 0.805 |

| Sleep Dysfunction | 14.4% | 41.7% | 0.221* | 0.818 |

indicates less than 80% power. SNOT-22, 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test.

DISCUSSION

Knowledge of what influences patients’ motivation to undergo elective ESS, as well as the various treatment modalities for control of symptoms of CRS, is vital to the shared decision-making process between patient and provider. The present study elucidates several important contributions to better understanding the underlying elements that influence patients to elect ESS and which outcomes can be reasonably expected from this intervention. Psychological and sleep dysfunction were significantly more likely to have a greater relative influence on patients electing surgical therapy than any of the sinus-specific symptom domains (Rhinologic, Extra-nasal rhinologic, Ear/facial symptoms). We found significant differential mean improvement across all domain scores within both treatment arms, but with the greatest improvements in the cohort electing sinus surgery. Furthermore, surgical and medical treatment modalities results in improvement across all domains, but subjects electing surgical interventions experience greater relative improvement.

The present study sought to further investigate the previous observation that baseline QOL scores is a significant predictor of treatment modality selection.2 No other study has investigated the types of symptoms that motivate patients to elect the upfront financial and physical cost burdens of ESS. We had anticipated that subjects with worse disease-specific symptoms would be more likely to elect surgical management. Current guidelines are focused on “cardinal” symptoms associated with CRS (thick nasal discharge, nasal airway obstruction, hyposmia, facial pain/pressure).10,15 These symptoms are often routinely followed in the clinic setting as a way to measure subjective disease burden or pursue further intervention. Prior study has shown that surgical management of CRS is more effective at controlling the cardinal symptoms in medically refractory patients than continued medical management.6 Surprisingly, however, disease-specific symptom burden was not predictive of electing surgical therapy. The decision to undergo surgical intervention is best predicted by health-related QOL domains pertaining to worse psychological impairment and sleep dysfunction. Subjects with a broader health-related burden of disease might be expected to elect a more aggressive intervention, but why do comparable symptoms lead to differential psychological impact?

Investigation into the connection between inflammation and the central nervous system is a relatively new field and only preliminary investigations into the interaction of CRS and sleep and psychological dysfunction have begun. In a contemporary review by Alt and Smith, CRS and sleep dysfunction are linked potentially through a range of mechanisms including nasal airway obstruction, efferent and afferent neural signaling, and brain-immune signaling via cytokines.16 Prior study has also shown that subjects with CRS without nasal polyps have higher psychological burden from disease than subjects with CRS with nasal polyps.3 These subjects with greater psychological burden had less rhinologic domain burden, but reported worse ear/facial symptoms. The pathways and immune-central nervous system interface summarized by Alt and Smith16 may help explain the differential impact of CRS subtype on the psychological domain observed by Browne and colleagues.3 A better understanding of this mechanism might help better target novel therapeutics to symptoms that most impact patients QOL and explain why some patients experience greater sleep and psychological impact from comparable physical symptoms.

Additional comorbidity may also differentially influence the health-related domains influencing subjects towards a more aggressive CRS intervention. For example, depression may independently influence sleep and psychological dysfunction domain scores. This confounding effect has already been observed in other chronic disease process like diabetes and depression, with depression exerting a differential impact on the underlying domains of the diabetes-specific survey.17 Several other potential comorbidities in CRS that potentially independently influence the sleep and psychological domains have been identified as potential risk factors for a limited response to ESS.18–20 Further investigation into the impact of these comorbidities on SNOT-22 domains scores would help illuminate whether or not failure to reach uniform optimal QOL outcomes for all patients was the result of inability to make improvements in the sleep and psychological dysfunction domains.

Given that subjects tend to be motivated to elect surgery by the general health-related QOL domains, we sought to further investigate the treatment impact on each domain. The question of the differential impact of an intervention on a given domain is an important issue to clarify prior to counseling a patient on treatment modality selection. Prior research efforts have predominantly been focused on outcomes of specific symptoms associated with the physical domains.6,21 Pynnonen and colleagues investigated the differential impact of nasal spray versus irrigation on SNOT-20 domains and found that only subjects using nasal saline irrigations experienced improvement in the sleep domain.4 In the present study, ESS and continued medical therapy results in improvement across all domains, but subjects electing ESS experience greater improvement. There is differential improvement across the domains with the greatest gains after surgery in the physical symptom domains and smallest gains in the health-related QOL domains. Further study on interventions in ESS should at least screen for a differential impact, and if one is found that would ideally be reported along with the aggregate scores.

This study has some important caveats, which warrant further discussion. The three sinus-specific symptom baseline domain scores were not statistically significantly different between our two treatment cohorts at the 0.050 level of significance. It may be possible that increased study sample size in the medical management subgroup would increase power to detect significant differences between these domain scores if one truly exists. In fact, analysis of standardized effect sizes (Table 7) involved post hoc power calculations which discovered 77%, 74%, and 46% power levels for the Ear/Facial symptom domain, Psychological Dysfunction domain, and Sleep dysfunction domain, respectively. Regardless of sample size, it should be noted that there is no pre-determined value to define a minimal clinically important difference for each discrete domain of the SNOT-22 instrument for which to delineate discernable patient improvement. There may also be sources of unmeasured confounding that may influence treatment selection as well as interval treatment outcomes inherent in this observational study.. For example, longer duration and severity of symptoms may significantly increase the likelihood that a patient elects a surgical intervention. Symptom duration and severity may also impact QOL domain measures differentially as well. Future study of the impact of symptom duration on treatment selection may clarify the role of this potential confounder. Additionally, there is cross-loading of survey items within each discrete domain, initially described in our original factor analysis of SNOT-22 item scores,5 which may not be replicable in survey responses obtained from other sub-types of adult sinusitis, in either surgical or non-surgical populations. Furthermore, these results are derived from subjects at four academic referral centers located across two separate countries and may not be externally generalizable to patient cohorts treated in a smaller, more general community setting or in patients with CRS who have not yet undergone maximum medical management for symptom maintenance.

CONCLUSION

The decision to elect ESS over continued medical management was found to be predicted more by the general health-related QOL domains surrounding sleep and psychological dysfunction. Patient treatment selection choice was found to be determined less by the sinus-specific symptom-related domains of CRS (Rhinologic, Extra-nasal Rhinologic and Ear/Facial symptoms). Endoscopic sinus surgery is a more effective intervention across all domains than continued medical therapy, but with a differential effect across discrete domains. Further investigation into why some patients carry greater sleep and psychological domain burdens may help better elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the chronic inflammation associated with CRS and identify novel therapeutics. Investigation into the differential impact of various comorbidities across domains may help clarify the significance of a given comorbidity.

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of Interest: None

Public clinical trial registration (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) #NCT01332136 entitled “Determinants of Medical and Surgical Treatment Outcomes in Chronic Sinusitis”

Accepted for oral presentation to the American Rhinologic Society at the annual American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery meeting, Orlando, Florida, September 20th, 2014 (Abstract submission #753).

Financial Disclosures: Timothy L. Smith, Peter H. Hwang, Jess C. Mace, and Zachary M. Soler are supported by a grant from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), one of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (R01 DC005805; PI/PD: TL Smith). Zachary M. Soler is also supported by another NIDCD grant (R03 DC013651-01). Timothy L. Smith is a consultant for IntersectENT, Inc (Menlo Park, CA.), which is not affiliated with this investigation. Todd E. Bodner, PhD is supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/Kaiser Permanente, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the U.S. Department of Defense, none of which are associated with this study.

References

- 1.Smith TL, Kern R, Palmer JN, et al. Medical therapy vs surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective, multi-institutional study with 1-year follow-up. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(1):4–9. doi: 10.1002/alr.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soler ZM, Rudmik L, Hwang PH, Mace JC, Schlosser RJ, Smith TL. Patient-centered decision making in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(10):2341–2346. doi: 10.1002/lary.24027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browne JP, Hopkins C, Slack R, Cano SJ. The Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT): Can we Make it More Clinically Meaningful? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(5):736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pynnonen MA, Kim HM, Terrell JE. Validation of the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 20 (SNOT-20) domains in nonsurgical patients. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23(1):40–45. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeConde AS, Bodner TE, Mace JC, Smith TL. Response shift in quality of life after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(8):712–719. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeConde AS, Mace JC, Alt JA, Soler ZM, Orlandi RR, Smith TL. Investigation of change in cardinal symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis after surgical or ongoing medical management. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/alr.21410. (in submission) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alt JA, Mace JC, Buniel MCF, Soler ZM, Smith TL. Predictors of Olfactory Dysfunction in Rhinosinusitis Using the Brief Smell Identification Test. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(7):E259–266. doi: 10.1002/lary.24587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alt JA, Smith TL, Mace JC, Soler ZM. Sleep quality and disease severity in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(10):2364–2370. doi: 10.1002/lary.24040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeConde AS, Mace JC, Alt JA, Schlosser JR, Smith TL, Soler ZM. Comparative effectiveness of medical and surgical therapy on olfaction in chronic rhinosinusitis: a prospective, multi-institutional study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(9):725–733. doi: 10.1002/alr.21350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Neil B, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 suppl):S1–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117 (3 Pt 2):S35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitus. Rhinology. 1993;31(4):183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins C, Gillett S, Slack R, Lund VJ, Browne JP. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34(5):447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccirillo JF, Merritt MG, Jr, Richards ML. Psychometric and clinimetric validity of the 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126(1):41–47. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.121022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, et al. EPOS 2012: European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. A summary for otorhinolaryngologists. Rhinology. 2012;50(1):1–12. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alt JA, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis and sleep: a contemporary review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(11):941–949. doi: 10.1002/alr.21217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carper MM, Traeger L, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ, Psaros C, Safren SA. The differential associations of depression and diabetes distress with quality of life domains in type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2014;37(3):501–510. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9505-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mace J, Michael YL, Carlson NE, Litvack JR, Smith TL. Effects of depression on quality of life improvement after endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(3):528–534. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31815d74bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeConde AS, Mace JC, Smith TL. The impact of comorbid migraine on quality of life outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2014 doi: 10.1002/lary.24592. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soler ZM, Mace J, Smith TL. Fibromyalgia and chronic rhinosinusitis: outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22(4):427–432. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chester AC, Antisdel JL, Sindwani R. Symptom-specific outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery: A systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(5):633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]