Abstract

Objective

This study possessed two aims: (1) to develop and validate aclinician -friendly measure of academic problem behavior that is relevant to the assessment of adolescents with ADHD and (2) to better understand the cross-situational expression of academic problem behaviors displayed by these youth.

Method

Within a sample of 324 adolescents with DSM-IV-TR diagnosed ADHD (age M=13.07, SD=1.47), parent, teacher, and adolescent self-report versions of the Adolescent Academic Problems Checklist (AAPC) were administered and compared. Item prevalence rates, factorial validity, inter-rater agreement, internal consistency, and concurrent validity were evaluated.

Results

Findings indicated the value of the parent and teacher AAPC as a psychometrically valid measure of academic problems in adolescents with ADHD. Parents and teachers offered unique perspectives on the academic functioning of adolescents with ADHD, indicating the complementary roles of these informants in the assessment process. According to parent and teacher reports, adolescents with ADHD displayed problematic academic behaviors in multiple daily tasks, with time management and planning deficits appearing most pervasive.

Conclusions

Adolescents with ADHD display heterogeneous academic problems that warrant detailed assessment prior to treatment. As a result, the AAPC may be a useful tool for clinicians and school staff conducting targeted assessments with these youth.

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; APA, 2013) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairing levels of inattention, overactivity, and poor impulse control that affects 5–10% of adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Though historically characterized as a childhood disorder, it is now well accepted that ADHD afflicts adolescents and adults (Molina et al., 2009; Wolraich et al., 2005). For adolescents with ADHD, academic functioning is regarded as the most critically impaired domain (Robin, 1998; Wolraich et al., 2005). Compared to non-ADHD peers, adolescents with ADHD perform more poorly on standardized achievement tests (Barkley et al., 1991; Fischer et al., 1990), complete fewer assignments (Barkley, Anastopoulos, Guevremont, & Fletcher, 1991; Kent et al., 2011; Weiss & Hechtman, 1993), and receive poorer course grades (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, Fletcher, 2006; Kent et al., 2011). These adolescents also are more likely to be absent from school (Barbaresi, Katusic, Colligan, Weaver, & Jacobsen, 2007) arrive late to classes (Kent et al., 2011), and be suspended for disciplinary incidents (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2002). Due to the multiple academic risks, course failure is common for adolescents with ADHD (Barkley et al., 1991, 2002, 2006; Kent et al., 2011), eventually leading to elevated rates of high school dropout (Barbaresi et al., 2007; Barkley et al., 2006; Kent et al., 2011). By some estimates, up to 38% of students with ADHD dropout of high school due to academic failure (Barkley et al., 2002).

The negative academic trajectory associated with ADHD begins in childhood (Barkley et al., 2006; Fischer, Barkley, Fletcher, & Smallish, 1993; Langberg et al., 2011; Lee & Hinshaw, 2006; Miller & Hinshaw, 2010) and these problems appear to escalate at the transition to secondary school (Langberg et al., 2008). Middle and high school represent a markedly different environment than elementary school, as adolescents attend multiple classes daily and complete much of their academic work outside of school (Eccles, 2004). Secondary school content teachers (e.g., Math, Science) instruct over 100 students a day for as little as 50 minutes per class, leaving teachers with little available time and resources to offer individual students (Benner & Graham, 2009). At the same time that teacher support diminishes, parents may increase expectations for academic independence, reducing homework supervision and academic support (Cooper, Lindsay, & Nye, 2000). Thus, academic success in secondary school requires self-management and independent execution of a variety of scholastic tasks across multiple settings. Individuals with ADHD may be particularly prone to failure in this environment due to established attention, executive functioning, and behavioral deficits (Barkley, Edwards, Laneri, Fletcher, & Metevia, 2001; Kent et al., 2011; Langberg, Dvorsky, & Evans, 2013).

For example, in each of their daily classes, successful adolescents must attend to and comply with teacher instructions, complete classwork accurately and expeditiously, retain material presented in lectures, and refrain from disruptive incidents. After leaving class, they must remember the details of homework assignments, complete homework with care in a timely manner, maintain possession of assignments until they are due, and remember to hand them in. Meanwhile, adolescents must gradually prepare for upcoming tests and long-term projects, systematically organize and retain information relevant to these tasks, and correctly follow instructions for task-completion (Eccles, 2004). Despite their probable risk for failure at multiple points in these processes (e.g., recording homework assignments, studying for tests, pacing work on long-term projects; Barbaresi et al., 2007; Barkley et al., 2002; Kent et al., 2011), almost no work diagrams common patterns of academic behavior displayed by adolescents with ADHD.

ADHD-related academic problems are behavioral manifestations of ADHD symptoms that lead toimpairment in a developmentally specific academic environment. Recognition of key academic problem behaviors is important for clinicians devising intervention plans, researchers developing effective treatments, and schools seeking to optimize educational environments for adolescents with ADHD. Subsequently, improved treatment tailoring hinges on effective identification of critical academic behaviors. Treating only classic ADHD-related academic problems (e.g., failing to raise hand, forgetting to bring materials to class, off-task behavior; Atkins, Pelham, & Licht, 1985) may overlook critical secondary school-specific problems. Therefore, it is not surprising that traditional school-based treatments for ADHD (e.g., stimulant medication, teacher-delivered behavioral interventions) display limited success in middle and high schools (Evans, Serpell, Schultz, & Pastor, 2007; Pelham et al., 2013). Improving the specificity of services available to these youth may first require mapping the full range of academic problems experienced by adolescents with ADHD.

Assessment of adolescent academic problems typically occurs through a combination of psychoeducational testing, direct observations, interviews, and adult-informant rating scales (Achenbach et al., 1987; Shapiro, 2011). Due to their convenience, cost-effectiveness, and documented utility, rating scales are perhaps the most widely utilized assessment tools for ADHD youth (Pelham, Fabiano, & Massetti, 2005). There is particular need for an assessment tool that evaluates ecologically valid problem behaviors that are related to ADHD symptoms and directly influence the academic performance of adolescents with ADHD. Measured academic problem behaviors should include both classic ADHD-related behaviors (e.g., failing to raise one’s hand, careless mistakes on work) and secondary school specific ones (e.g., failing to take class notes, leaving long-term projects until the last minute), which co-occur in adolescence. Furthermore, for a scale to directly inform intervention, it must assess the most common behavioral mechanisms of failure in this population. A multi-informant approach is necessary to adequately detect these behavioral mechanisms because adolescents with ADHD change academic settings throughout the day.

The most commonly employed broadband and narrowband clinical rating scales (e.g., Abikoff & Gallagher, 2008; Achenbach, 1991; Anesko, Schoiock, Ramirez, & Levine, 1987; DuPaul, Rapport, & Perriello, 1991; Gioia, Isquith, Guy, & Kenworthy, 2000; Goyette, Conners, & Ulrich, 1978; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) possess an academic item pool derived from problems noted in elementary school children and do not include secondary school specific items (Achenbach, 1991; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2006), preventing measurement of the full breadth of academic problem behaviors in adolescence. These scales regularly are used to evaluate academic problems in adolescents with ADHD (e.g., classroom performance, executive functioning, homework; Robin, 1998; Langberg, Epstein, Becker, Girio-Herrera, & Vaughn, 2012; Meyer & Kelley, 2007), despite not being developed for or validated with this population. One scale was designed to assess academic problems in adolescents with ADHD (Classroom Performance Survey; Brady et al., 2012), but this scale is limited in that it: (1) assesses problems in only one setting, (2) possesses a limited item pool that was not empirically derived, and (3) is yet to be validated in an ADHD sample.

In the current study, we evaluate the psychometric evidence for abehavioral rating scale (Adolescent Academic Problems Checklist; AAPC) that measures academic problem behaviors thought to be (1) associated with ADHD in the secondary school setting and (2) critical mechanisms of failure and therefore targets for intervention in these youth. Because frequent academic setting changes are endemic to adolescence (Eccles, 2004), a multi-informant (parent, teacher, self) assessment strategy was adopted to maximize information collection (Pelham et al., 2005). We describe each stage of scale development with particular attention to inter-rater agreement, factor structure, internal consistency, and concurrent validity. Due tothe limited validity of self-report by adolescents with ADHD (Fischer, Barkley, Fletcher, & Smallish, 1993; Sibley et al., 2012), we hypothesized significant agreement between parent and teacher, but not self-reports of academic problems. We also hypothesized that the AAPC would display a multi-factorial structure with extracted factors representing identified ADHD-related deficits (e.g., executive functioning, academic skills, behavior problems). We hypothesized that the emergent subscales, as well as the full AAPC, would possess strong internal consistency and concurrent validity. Based on previous work (e.g., Langberg et al., 2013), we also examined item prevalence rates, hypothesizing that behaviors associated with executive functioning deficits would be the most prominent problems endorsed by informants.

Method

Participants

Data for the current study was collected from adolescents with ADHD (N=342) who enrolled in a psychosocial treatment study between 2010–2013 at an ethnically diverse urban university clinic. During these years, four separate psychosocial trials enrolled adolescents with DSM-IV-TR ADHD as part of a research program to develop effective treatments for ADHD in adolescence. Each participant occurs only once in the dataset. All data was collected from parents, adolescents, and teachers at initial presentation tothe research clinic as part of a standard battery for adolescents with ADHD. With the exception of participant grade level requirements (e.g., middle school, high school) inclusion criteria and recruitment, diagnostic, and assessment procedures were uniform across studies. To participate in research, adolescents were required to: meet DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD, be enrolled in school, have an estimated IQ of 80 or higher, and have no history of an autism spectrum disorder. Table 1 lists characteristics of the total sample.

Table 1.

Demographic and Diagnostic Characteristics of the Sample

| Demographic | |

|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 13.07 (1.47) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Male | 70.5 |

| Female | 29.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 9.0 |

| Hispanic Any Race | 77.5 |

| Black/African-American (Non-Hispanic) | 9.9 |

| Asian | 0.6 |

| Mixed Race | 3.0 |

| Highest Parent Education Level | |

| High school or less | 18.7 |

| Some college or technical training | 21.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 37.8 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 22.2 |

| Single Parent Household (%) | 34.8 |

| Diagnostic | |

| Estimated Full Scale IQ M (SD) | 98.82 (12.50) |

| Reading Achievement Standard Score M (SD) | 100.07 (13.02) |

| Math Achievement Standard Score M (SD) | 96.51 (16.18) |

| DSM-IV-TR ADHD Diagnosis (%) | |

| ADHD-PI | 36.8 |

| ADHD-C | 62.3 |

| ADHD-PH/I | 0.9 |

| LD (%) | 16.8 |

| ODD (%) | 41.5 |

| CD (%) | 9.1 |

| Current ADHD Medication (%) | 44.7 |

Procedures

Participants were recruited through school mailings and parent inquiries at the university research clinic. For all potential participants, the primary caretaker was administered a brief phone screen containing DSM-IV-TR ADHD symptoms and questions about daily impairment. Families were invited to an intake to determine study eligibility if the parent endorsed on the phone screen: (1) a previous diagnosis of ADHD OR four or more symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity (APA, 2000) AND (2) clinically significant functional impairment (at least a “3” on the “0 to 6” Impairment Rating Scale; IRS; Fabiano et al., 2006).

At intake, informed parental consent and youth assent were obtained and study eligibility was assessed. The primary caretaker participated in the assessment, but when available, other parents were encouraged to provide supplemental report. ADHD diagnosis was assessed through parent structured interview (Computerized-Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children) and parent and teacher rating scales (Shaffer, Fischer, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000; Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992)based on standard practice recommendations (Pelham et al., 2005). The clinician administered brief intelligence and achievement tests (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; Wechsler, 2003, 2011; Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Wechsler, 2002, 2011) and a standard rating scale battery. After parents signed a release of information for the school, ratings were obtained directly from the core academic teacher (i.e., Math, Science, Social Studies, Language Arts) who was reported to teach the class in which the adolescent struggled most. Cross-situational impairment was assessed for the purpose of ADHD diagnosis by examining parent and teacher impairment ratings and school grades obtained from official report cards. Impairment was defined as: (a) parent and teacher endorsement of a “3” or higher on the IRS (7-point scale, Fabiano et al., 2006) and (b) academic impairment present in assignment-level school grades (e.g., failing to turn-in greater than 20% of assignments during the last month or possessing a grade of D or F during the last month in at least one class). Doctoral level psychologists conducted dual clinician review to determine diagnosis and study eligibility and consulted a third psychologist when disagreements occurred. All missing data was screened at the time that assessments occurred and research assistants were trained to query missing items before parents left the clinic and as soon as teacher ratings were received.

AAPC Development

The initial impetus for developing the AAPC was to create a clinician-friendly tool for identifying observable academic problem behaviors in adolescents with ADHD and selecting intervention targets. Scale development procedures adhered to guidelines offered by experts (Clark & Watson, 1995; DeVellis, 2011) and were customized to the goal of obtaining an ecologically valid measurement tool for secondary school academic problems associated with ADHD. The first step in AAPC development was systematically coding qualitative descriptions of presenting problems offered by the parents and teachers of 34 adolescents with ADHD who presented for treatment at a university clinic-based intensive summer treatment program from 2008–2009. Parents were asked to list presenting problems during an unstructured clinical interview and on the narrative form of the IRS (Fabiano et al., 2006). Teachers were asked to describe presenting problems on the narrative form of the IRS and on a target behavior form that asked teachers to list possible treatment targets. Using a procedure outlin ed by Merriam (1998), research team members extracted unique segments of data that represented each presenting problem listed by informants across measures. All data segments were then clustered according to common behavioral theme. For example, “forgets to write in a daily planner” and “doesn’t write down homework in his agenda” were considered to represent the same presenting problem and were grouped accordingly. Through this process, 25 repeatedly mentioned academic problem behaviors were selected as potential items for the AAPC. Consistent with standard ADHD symptom rating scales (e.g., DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998; Pelham et al., 1992), respondents rated specific academic problem behaviors as occurring on a four point scale: (0) not at all, (1) just a little, (2) pretty much, or (3) very much.

As mentioned, the 25-item AAPC was a part of a standard battery completed by parents, teachers, and adolescents pursuing psychosocial treatment at the study team’s research clinic. In a recently published controlled evaluation of one such treatment (Sibley et al., 2013), strong internal consistency was reported for the parent (.91) and teacher (.96) AAPC. A large group x time treatment effect (d=1.30) was present on the parent AAPC, indicating sensitivity to changes produced during behavioral treatment. In this initial administration of the AAPC, it was clear that most informants failed to respond to a single item (“has a poorly organized locker”) due to lack of opportunity to observe. As a result, this item was removed from the AAPC.

Measures of Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Grade Point Average (GPA)

At baseline, official report cards were obtained directly from the school district or from parents. GPA for each academic quarter was calculated by converting all core academic grades to a 4-point scale (i.e., 4.0=A, 3.0=B, 2.0=C, 1.0=D, 0.0=F). Grades were not weighted for class difficulty. GPA for the quarter in which the baseline assessment occurred was utilized as a measure of convergent validity.

Functional Impairment

The IRS was administered to parents and teachers at baseline (Fabiano et al., 2006). Parents and teachers indicated impairment severity in seven domains by marking an X on a line representing the continuum from “no problem” to “extreme problem.” Responses were coded 0 (no impairment) to 6 (extreme impairment). Informants also provided a narrative description of the impairment in each domain. The academic impairment, relationship with adult, and classroom disruption items were used to assess convergent and discriminant validity. The IRS demonstrates strong concurrent, predictive, convergent, and discriminant validity and accurately discriminates individuals with and without ADHD (Fabiano et al., 2006). It may be used to identify impairment in adolescents with ADHD across settings and informants (Evans et al., 2013).

ADHDSymptoms

Each participant’s level of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity (H/I) symptom severity was measured at baseline using the Disruptive Behavior Disorder Rating Scale (DBD; Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992). The DBD is a DSM-IV symptom rating scale that was completed by parents and teachers. Respondents are asked to rate symptoms of ADHD as not at all present (0), just a little (1), pretty much (2), or very much (3). In order to calculate an index of symptom severity the average level (0–3) of each item on the inattention and H/I subscales was calculated for each participant. The psychometric properties of the DBD are very good for child and adolescent samples, with empirical support for distinct inattention and H/I and internally consistent subscales with alphas above .95 (Evans et al., 2013; Pelham et al., 1992; Pillow, Pelham, Hoza, Molina, & Stultz, 1998; Sibley et al., 2012).

Analytic Plan

Inter-rater Endorsement

Item endorsement rates were directly compared by rater (parent, teacher, self) for each AAPC item. For each direct comparison (parent vs. teacher, parent vs. self, teacher vs. self), McNemar’s chi-square test of marginal probability was used to compare overall item endorsement rates using an SPSS Macro (Newcombe, 1998). To assess case-wise inter-rater agreement, Spearman’s rank order correlation was calculated to assess the strength of the association between item scores reported by parents, teachers, and adolescents. We also conducted an exploratory analysis to assess whether certain items might be more relevant to younger vs. older adolescents. To correct for multiple comparisons, alpha-level was set at p<.002 for all item endorsement analyses.

Exploratory Factor Structure

As these analyses represent the initial phase of AAPC development, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted to investigate the underlying factor structure of the parent and teacher administered scales. Given the categorical nature of the AAPC responses and the expectation of a unique but correlated multifactorial structure, analyses were conducted in Mplus 6.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2010) using an oblique Geomin rotation and a Weighted Least Squares mean-adjusted estimator (WLSM). One, two, three, and four factor solutions were explored and compared for model fit and theoretical parsimony using a multi-method procedure. Scree plots, initial eigenvalues, and three fit indices (CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR) were inspected for each solution and interpreted using standard guidelines (Costello & Osborne, 2005). Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference tests (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) were conducted between nested factorial solutions to further evaluate the relative fit of each model. Pattern coefficient loadings were inspected for the statistically optimal parent and teacher AAPC factorial solutions and a coefficient of .40 was considered to be practically significant based on sample-size specific recommendations (Velicer & Fava, 1998).To arrive at a final solution, the statistically optimal solution was considered in the context of existing theory and adjustments were made where statistical and theoretical evidence suggested a need for modification.

Internal Reliability

For the parent and teacher AAPC, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each factor and the entire scale. In cases of unacceptable internal consistency, Spearman’s rank order correlations were examined between individual items and the corresponding factor score to identify sources of poor internal consistency.

Concurrent Validity

Pearson’s bivariate correlations were obtained between parent and teacher AAPC total scores and subscale scores, and seven variables with theoretical linkages. Convergent validity was measured with academic impairment, GPA, inattention, and hyperactivity/impulsivity severity, and classroom disruption (parent or teacher rated). Discriminant validity was measured by IQand relationship quality with the rater. To correct for multiple comparisons, alpha-level was set at p<.002.

Results

Inter-rater Endorsement

Item endorsement rates for each rater are presented in Table 2. Across items, adolescents endorsed problem behaviors at significantly lower rates than both parents and teachers. The exceptions to this finding were two items related to school attendance (skips class, arrives late to class), which were endorsed at a low rate by all raters (see Table 2). For 19 out of 24 items (see Table 2), parent and teacher endorsement rates did not significantly differ. However, parents reported significantly higher rates of refusing to do work, having difficulty organizing writing assignments, noncompliance with adult requests, and leaving assignments until the last minute. Teachers reported significantly higher rates of failing to raise one’s hand before speaking in class. Correlations between parent, teacher, and adolescent reports of item severity were modest, though typically significant (see Table 2). Average correlations were as follows:.24 for parent and teacher reports,.24 for parent and student reports, and.20 for student and teacher reports. Following the conclusion that adolescents did not provide valid reports on the AAPC, we did not conduct additional analyses for the self-report version.

Table 2.

AAPC Endorsement Rates and Inter-rater Agreement

| Endorsement (%) | Χ2 | Spearman’s rho | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | T | S | P-T | T-S | P-S | P-T | T-S | P-S | |

|

| |||||||||

| Fails to take class notes | 66.0 | 65.0 | 22.2 | 0.07 | 117.64** | 111.48** | .20** | .26** | .16* |

| Receives poor grades on tests/quizzes | 64.3 | 62.8 | 18.9 | 0.23 | 129.6** | 137.89** | .32** | .22** | .31** |

| Does not follow through on homework instructions | 70.3 | 65.2 | 17.9 | 2.70 | 143.15** | 163.55** | .29** | .27** | .24** |

| Is disruptive in class | 28.9 | 29.5 | 14.5 | 0.05 | 29.07** | 23.51** | .48** | .37** | .38** |

| Does not follow through on class instructions | 62.5 | 58.5 | 10.4 | 1.42 | 140.25** | 154.71** | .24** | .24** | .26** |

| Arrives late for class | 9.7 | 10.6 | 6.4 | 0.22 | 5.16* | 3.46 | .36** | .26** | .36** |

| Does not study for tests/quizzes | 65.4 | 59.9 | 27.5 | 2.49 | 64.47** | 90.59** | .12* | .11* | .12* |

| Turns in work that was not completed thoroughly | 64.8 | 63.6 | 15.6 | 0.13 | 129.05** | 141.65** | .24** | .06 | .12* |

| Has poorly organized folders or binders | 73.5 | 64.6 | 28.6 | 7.31* | 87.19** | 131.58** | .29** | .26** | .40** |

| Forgets to bring appropriate materials to class | 60.1 | 54.1 | 20.2 | 3.28 | 83.63** | 116.16** | .26** | .23 ** | .34** |

| Fails to turn in already completed homework | 55.7 | 48.6 | 17.3 | 4.04* | 70.35** | 98.56** | .23** | .14* | .20** |

| Fails to turn in assignments on time | 60.9 | 58.7 | 20.8 | 0.44 | 99.84** | 113.65** | .30** | .25** | .34** |

| Actively refuses to complete work. | 34.1 | 20.7 | 7.0 | 17.29** | 25.63** | 72.67** | .36** | .24** | .18** |

| Has difficulty organizing writing assignments | 73.2 | 58.6 | 22.9 | 16.03** | 81.46** | 140.25** | .21** | .19** | .26** |

| Is noncompliant with adult requests | 37.0 | 20.5 | 12.8 | 26.51** | 7.91* | 50.74** | .29** | .22** | .19** |

| Makes careless errors on work | 74.5 | 64.7 | 20.7 | 8.26* | 120.14** | 151.35** | .08 | .10 | .09 |

| Fails to record homework in daily planner/agenda | 74.0 | 67.2 | 37.3 | 3.97* | 60.46** | 96.01** | .24** | .29** | .39** |

| Fails to participate in class discussions | 25.0 | 34.7 | 11.6 | 8.98* | 48.04** | 21.25** | .29** | .21** | .21** |

| Is off-task during school work | 60.4 | 62.2 | 16.2 | 0.27 | 124.6** | 128.99** | .15* | .13* | .21** |

| Fails to raise hand before speaking in class | 27.9 | 42.3 | 15.4 | 18.89** | 60.62** | 18.18** | .36** | .29** | .36** |

| Leaves longer-term projects until the last minute | 82.9 | 66.6 | 29.3 | 21.87** | 71.11** | 144.61** | .09 | .06 | .18* |

| Skips class for unexcused reasons | 4.4 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.29 | .17* | .16* | .23** |

| Poor time management | 75.2 | 66.7 | 16.2 | 6.43* | 145.59** | 181.70** | .10 | .10 | .14* |

| Has difficulty getting started on assignments | 76.7 | 68.0 | 23.6 | 7.07* | 116.81** | 153.35** | .11* | .05 | .14* |

Note. P=parent; T=teacher; S=self; Χ2 represents McNemar’s uncorrected statistic with significant values indicating differences between raters. r represents Spearman’s bivariate correlation with significant values indicating agreement between raters.

For most items, there was no association between age and endorsement rate. The exception was parent report of two items: arrives late to class (r=.21, p<.001) and skips class (r=.27, p<.001) and teacher report of one item: fails to record homework in daily planner (r=.17, p=.002). These data indicate that older adolescents who are in high school may be more likely than middle school students with ADHD to have attendance problems and fail to use a daily planner.

Exploratory Factor Structure

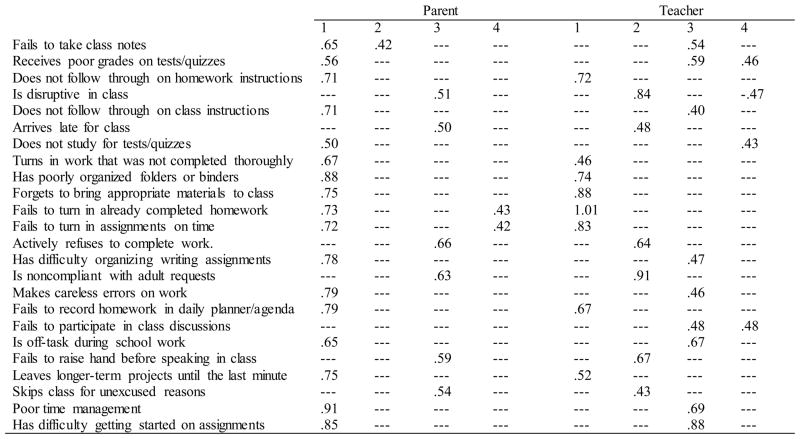

For the parent AAPC, initial eigenvalues and scree plot examination initially suggested a four-factor solution (EEVA1= 11.25, EEVA2= 2.17, EEVA3= 1.24, EEVA4= 1.09).Although the one -factor [χ2(252)= 1710.38; CFI=.96, RMSEA=.13, SRMR=.09], two-factor [χ2(229)= 1039.20; CFI=.98, RMSEA=.10, SRMR=.06], three-factor [χ2(207)= 751.39; CFI=.98, RMSEA=.09, SRMR=.05], and four-factor [χ2(186)= 557.31; CFI=.99, RMSEA=.08, SRMR=.04] models all possessed acceptable model fit, chi-square difference tests indicated that the two-factor solution provided significantly stronger fit than the one-factor solution [χ2(23) = 337.00], the three-factor solution provided significantly stronger fit than the two-factor solution [χ2(22) = 187.47], and the four-factor solution provided significantly stronger fit than the three-factor solution [χ2(21) = 133.37]. Examination of factor loadings for the four-factor solution (see Figure 1) suggested that factor 1 represented a broad academic skills factor containing 19 of the 24 AAPC items. Factor 2 contained only three items, all of which possessed small loadings that cross-loaded on factor 1. There was no clear theoretical meaning to factor 2. Factor 3 represented a disruptive behavior factor containing six items: disruptive in class, arrives late to class, refuses to complete work, noncompliance, failure to raise hand in class, and skipping class. Factor 4 appeared to represent a class preparation/forgetfulness factor containing five items: arriving late to class, forgets materials, fails to turn in homework he/she already completed, fails to turn in assignments on time, and skips class. All items on factor 4 cross-loaded with either factor 1 or factor 3 and were modest in magnitude (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Four-factor Solutions for Parent and Teacher AAPC

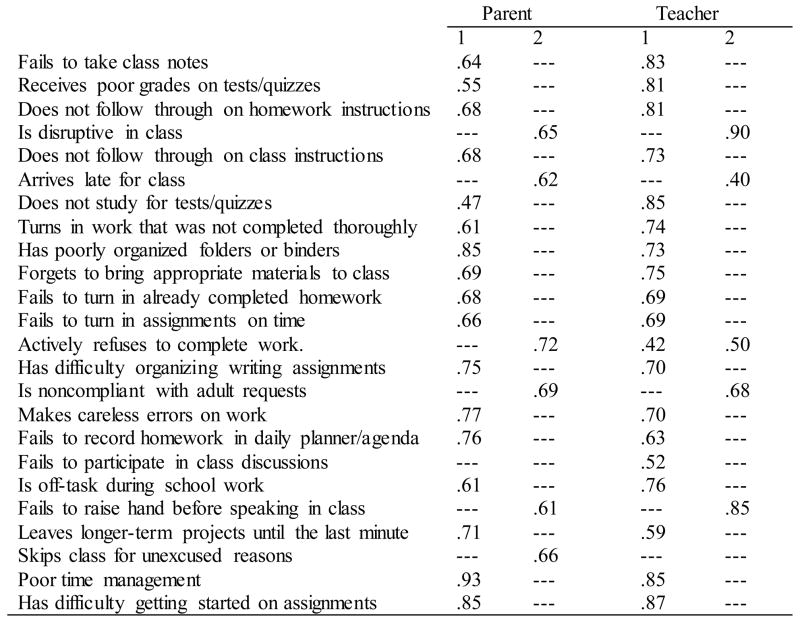

Only factors 1 and 3 appeared to represent theoretically meaningful and statistically robust factors. Rotated loadings for factors 2 and 4 primarily subsumed residual variance from items with meaningful loadings on factors 1 and 3. Consequently, the two-factor solution was reexamined and chosen as the most parsimonious solution (see Figure 2). Factor 1 represented an academic skills index and factor 2 a disruptive behavior index (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Two-factor Solutions for Parent and Teacher AAPC

For the teacher AAPC, initial eigenvalues and scree plot examination also initially suggested afour -factor solution (EEVA1= 12.13, EEVA2= 2.38, EEVA3= 1.42, EEVA4= 1.02). Although the one-factor [χ2(252)= 3092.32; CFI=.94, RMSEA=.18, SRMR=.10], two-factor [χ2(229)= 1460.03; CFI=.98, RMSEA=.13, SRMR=.06], three-factor [χ2(207)= 951.77; CFI=.99, RMSEA=.10, SRMR=.05], and four-factor [χ2(186)= 576.65; CFI=.99, RMSEA=.08, SRMR=.04] models all possessed acceptable model fit, chi-square difference tests indicated that the two-factor solution provided significantly stronger fit than the one-factor solution [χ2(23) = 621.89], the three-factor solution provided significantly stronger fit than the two-factor solution [χ2(22) = 378.65], and the four-factor solution provided significantly stronger fit than the three-factor solution [χ2(21) = 219.60]. Examination of factor loadings (see Figure 1) suggested that factor 1 was represented by 13 items theoretically bound to a latent organization skills construct (e.g., forgets to bring materials to class, fails to turn in completed homework, fails to turn in assignments on time). Factor 2 contained six items that represented disruptive classroom behavior (e.g., is disruptive in class, is noncompliant with adult requests). Factor 3 represented a factor with 11 items best characterized asa time management factor (e.g., is off-task during school work, poor time management, has difficulty getting started on assignments). Notably, there were five items that cross-loaded on factors 1 and 3 and possessed modest loadings on both factors (see Figure 1). Factor 4 appeared to represent an academic disengagement factor and was characterized by five items, most notably non-participation in class. Factors 3 and 4 were primarily comprised of items with modest factor loadings and primary loadings on either factor 1 or 2. Thus, the two-factor model was reexamined and found to represent the most parsimonious solution (see Figure 2). F actor 1 represented an academic skills index and factor 2 represented a disruptive behavior index. One item (actively refuses to complete work) cross-loaded but was assigned to the factor that possessed the larger loading (factor 2).

Internal Reliability

Total score alphas were excellent for the 24-item parent (.92) and teacher (.92) AAPC. Internal consistency was strong for factor 1 (17 academic skills items) for both the parent (alpha=.94) and teacher (alpha=.92) scales. For factor 2(6 items, disruptive behavior), parent and teacher alphas were initially unacceptable (.65-.66). However, examination of Spearman rank order correlations between each item and the factor subscore, as well as factor loading magnitudes (see Figure 2) suggested that the two attendance variables (arrives late to class, skips class) were only loosely related to the factor 2 construct. After removing these items from the factor 2 scale, internal consistency was acceptable for the teacher (alpha=.81), but not the parent (alpha=.63) scale. However, because the two removed items appropriately contributed to the AAPC total score index and also may be clinically meaningful (especially to older adolescents as noted above), they were retained on the final scale. Thus, it was concluded that the parent and teacher AAPC total score and academic skills indices, as well as the teacher disruptive behavior index, possessed adequate reliability when measuring the academic behavior of adolescents with ADHD.

Concurrent Validity

Table 3& 4 present relevant intercorrelations for parent AAPC total score and academic skills index, as well as the teacher AAPC total score and academic skills and disruptive behavior indices. Results for the parent AAPC (see Table 3) indicated that the total score and academic skills subscale possessed a significant positive correlation with parent ratings of academic impairment, inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and the parent’s relationship with the child. The parent AAPC total score, but not the academic skills subscale score, possessed a significant negative correlation with GPA. Neither parent AAPC score possessed a significant correlation with IQ. Both the parent AAPC total score and academic skills subscale scores were most strongly associated with parent ratings of academic impairment. For the teacher AAPC, the AAPC total score as well as both subscales possessed significant correlations in the expected direction with all variables except IQ. The teacher AAPC total score and academic skills subscale possessed the strongest correlation with inattention symptoms, whereas the disruptive behavior subscale was most strongly correlated with hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations between Study Variables and the Parent AAPC

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| (1) Parent AAPC Total Score | --- | |||||||

| (2) Parent AAPC Academic Skills Index | .96* | --- | ||||||

| (3) Parent Academic Impairment | .47* | .48* | --- | |||||

| (4) GPA | −.28* | −.22* | −.20* | --- | ||||

| (5) Parent Inattention Symptoms | .46* | .44* | .39* | −.10 | --- | |||

| (6) Parent H/I Symptoms | .23* | .15 | .17 | −.13 | .51* | --- | ||

| (7) IQ | .03 | .04 | .10 | .25* | .15 | .03 | --- | |

| (8) Relationship with Parent | .40* | .36* | .35* | .04 | .37* | .31* | .23* | |

Note. Parent-rated academic impairment and relationship with parent measured by the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; Fabiano et al., 2006); Parent Inattention and H/I symptoms measured by the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD; Pelham et al., 1992); IQ measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 2003)

p<.002

Table 4.

Bivariate Correlations between Study Variables and the Teacher AAPC

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Teacher AAPC Total Score | --- | ||||||||

| (2) Teacher Academic Skills Index | .97* | --- | |||||||

| (3) Teacher Disruptive Behavior Index | .65* | .45* | --- | ||||||

| (4) Teacher Academic Impairment | .57* | .58* | .28* | --- | |||||

| (5) GPA | −.39* | −.38* | −.23* | −.30* | --- | ||||

| (6) Teacher Inattention Symptoms | .85* | .84* | .51* | .57* | −.30* | --- | |||

| (7) Teacher H/I Symptoms | .49* | .38* | .68* | .21* | −.12 | .55* | --- | ||

| (8) Teacher Classroom Disruption | .38* | .31* | .43* | .30* | −.07 | .37* | .43* | --- | |

| (9) IQ | −.16 | −.15 | −.10 | −.12 | .25* | −.15 | −.08 | −.08 | --- |

| (10) Relationship with Teacher | .32* | .29* | .28* | .28* | −.12 | .32* | .25* | .28* | −.02 |

Note. Parent-rated academic impairment and relationship with parent measured by the Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; Fabiano et al., 2006); Parent Inattention and H/I symptoms measured by the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD; Pelham et al., 1992); IQ measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 2003)

p<.002

Discussion

This study offers information about the academic problems of adolescents with ADHD and validates a practical and relevant tool for assessing school problems in these youth. Specific findings were that: (1) the AAPC possessed a two-factor solution (academic skills and disruptive behavior) and these factors, as well as the AAPC total score, appeared to be valid and reliable indices of academic functioning in adolescents with ADHD; (2) parents and teachers offered unique perspective on the academic functioning of adolescents with ADHD, indicating the complementary roles of these informants in the assessment process; and (3) adolescents with ADHD displayed academic problems at multiple points in the academic process, but time management and planning deficits were most prevalent. Each finding is discussed below.

The AAPC specifically was designed to detect academic behaviors that may contribute to impairment in adolescents with ADHD. To obtain an accurate scope of items, scale development began with a bottom-up approach: coding qualitative parent and teacher reports of school behaviors in a clinical sample of adolescents with ADHD. Subsequent psychometric analyses suggested that the parent and teacher AAPCs provide reliable and valid overall indices of academic problems within this population (AAPC total score). The AAPC total score displayed excellent internal consistency and strong concurrent validity and possessed expected correlations with variables in its nomological network. Furthermore, factor analyses suggested that unique academic skills and disruptive behavior dimensions underlie the AAPC—though internal consistency for the disruptive behavior dimension was unacceptable for parent report (discussed below). For parent and teacher reports, the academic skills index correlated strongly with inattention severity, academic impairment, and GPA. The teacher disruptive behavior index was highly correlated with H/I severity and classroom disruption. Thus, the AAPC appears to serve as a valid measure of academic impairment for adolescents with ADHD.

As noted, parents and teachers provided valid reports of adolescent academic problems. Overall, parents and teachers reported similar sample-wide rates of academic problems in adolescents with ADHD, suggesting that the presence of academic problems in adolescents with ADHD is global and pervades setting. However, consistent with previous literature (Evans et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 1993; Sibley et al., 2012), adolescents endorsed very little impairment compared to reports offered by parents and teachers. These data suggest that adolescents with ADHD do not provide accurate reports of their school functioning; however, it still may be useful to assess an adolescent’s perception of his/her school functioning to probe insight or communicate that he/she is central in the treatment process. Thus, clinicians are encouraged to obtain adolescent reports of academic functioning, but to interpret these data with caution.

Despite parent-teacher agreement on item prevalence rates, parent-teacher agreement for item severity was modest (see Table 2), indicating informant disagreement about behavioral expression. Informant discrepancies are common in clinical samples of children (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987; DuPaul, 1991; Mitsis, McKay, Schultz, Newcorn, & Halperin, 2000; Wolraich et al., 2004) and are also documented in samples of adolescents with ADHD (Fischer et al., 1993; Sibley et al., 2012). These discrepancies may indicate cross-situational variability in symptom expression (Schachar, Rutter, & Smith, 1981) or a lack of opportunity for some informants to observe particular behaviors. For example, parents were more likely than teachers to report refusing to do work, difficulty organizing writing assignments, noncompliance with adult requests, and leaving long-term assignments until the last minute. Higher rates of defiance and time management problems at home may reflect the nature of home academic tasks or a tendency for elevated parent-adolescent conflict in adolescence (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Alternatively, teachers reported significantly higher rates of classroom behavior problems, such as failing to raise one’s hand before speaking in class. The latter finding suggests that parents may be inappropriate informants of classroom behavior—a finding that is further reflected in the poor internal consistency of the parent disruptive behavior index. This finding is not surprising given the noted decline in home-school communication at the transition to secondary school; some parents may be unaware of school behavior problems below the threshold of disciplinary referral. On the other hand, when teacher reports are unavailable, parents’ information about classroom behavior may be useful— in our sample, 28.9% of parents were aware of adolescent classroom behavior problems (see Table 2). It is important to note that both home and school academic problems contributed to GPA (see Tables 3 & 4), underscoring the importance of home-school communication in treatment planning and a multi-informant assessment strategy for adolescents with ADHD.

Compared to parent ratings, teacher AAPC scores correlated more strongly with impairment, symptom ratings, and GPA (see Tables 3 & 4). This finding may suggest that teachers provide more valid report of academic functioning; however, in some instances, the correspondence between the teacher AAPC and related variables appeared unexpectedly high (e.g., with inattention). It may be the case that teachers exhibit more prominent method effects than parents due to a tendency to develop overly negative global views of youth with ADHD based on observed domain-specific problems (i.e., halo effects; Costello, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1991). However, it is also possible that teacher ratings of symptoms and impairment correlate more strongly with the AAPC because teachers consider only the academic domain when rating students on global indices. Parents, on the other hand, observe adolescents in multiple domains each day (e.g., recreational, home behavior, academic), which may lead to a lower correspondence between global symptom and impairment ratings and observations of domain-specific behavior. Overall, evidence suggests that teacher reports of functioning are necessary to conduct a thorough assessment of an adolescent with ADHD. Despite documented barriers to collecting teacher ratings in secondary school settings (Evans, Allen, Moore, & Strauss 2005), clinicians should make appropriate efforts to obtain this information.

Parent and teacher reports universally indicated that academically impaired adolescents with ADHD display high levels of problem behaviors at multiple points in the academic process. As they move through the day, a majority of these youth fail to take class notes, produce poorly organized and careless classwork, forget to record homework in a daily agenda, place assignments in poorly organized folders, and fail to follow instructions on homework. However, most notably, parents and teachers reported especially prominent problems with time management and planning deficits (see Table 2), which is consistent with previous work (Langberg et al., 2013). Unlike their childhood counterparts (Abikoff et al., 2002), a majority of academically impaired adolescents with ADHD did not display disruptive classroom behavior—which is notable given that the current sample is clinic-referred. This finding likely reflects developmental differences in the expression of ADHD in adolescence (Wolraich et al., 2005) and suggests that ADHD-related mechanisms of academic failure may be qualitatively distinct in childhood and adolescence. More sophisticated work is needed to model processes that contribute to academic problems amongst adolescents with ADHD.

The results of this study should be considered within the context of its limitations. First, the study’s sample was clinic-referred and consequently may possess higher rates of academic problems than community samples of adolescents with ADHD. When qualitatively sorting potential items on the AAPC scale, we did not systematically collect inter-rater reliability data. Additionally, this study did not include a comparison group of typically developing youth. Therefore, it is not possible to evaluate whether AAPC items discriminate between youth with and without ADHD. Also unclear is the extent to which typically developing youth display problems listed on the AAPC. Furthermore, if a typically developing adolescent displays the problems on the AAPC, these problems may not necessarily lead to academic failure (e.g., failing to write in a daily planner may not be impairing when one does not display symptoms of forgetfulness). Thus, the AAPC items may only represent mechanisms of academic failure for ADHD adolescents, not other academically impaired populations. Future work on the academic problems of adolescents with ADHD should incorporate non-ADHD peers to expand the information base.

In sum, adolescents with ADHD display multifaceted academic problems, though time management and planning problems may be most pervasive. Within this population, there is substantial variability in the presence and severity of academic behavior problems. As a result, detailed assessment of a variety of academic problem areas is necessary to obtain an accurate case conceptualization. Integration of parent and teacher reports of academic functioning is key as some problem behaviors may occur only at home or school and problems in both settings are significantly related to GPA. With reliable and valid parent and teacher versions, the AAPC may be a useful tool to clinicians who wish to conduct a brief assessment of academic problems that yields clear idiographic targets for an adolescent with ADHD’s treatment. The AAPC’s item pool was derived from qualitative reports of adolescents with ADHD, the scale is well-validated in a sample of adolescents with ADHD, and it assesses both classic and secondary-school specific academic problem behaviors. Additionally, the AAPC may serve as a way to monitor response to psychosocial (Sibley et al., 2013), and potentially medication, treatment. Finally, these results suggest a need to disseminate treatments that target time management and planning deficits in adolescents with ADHD (e.g., Evans et al., 2011; Langberg et al., 2012; Sibley et al., 2013), as these interventions may be most effective at reducing the widespread academic problems of these youth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34MH092466) and the Institute of Education Sciences (R324A120169).

References

- Abikoff HA, Gallagher R. Assessment and remediation of organizational skills deficits in children with ADHD. In: McBurnett K, Pfiffner L, editors. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Concepts, controversies, new directions. New York, NY: Information Healthcare USA; 2008. pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Abikoff HB, Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Hoza B, Hechtman L, Pollack S, Wigal T. Observed classroom behavior of children with ADHD: Relationship to gender and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:349–359. doi: 10.1023/a:1015713807297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlighton, VT: Author; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anesko KM, Schoiock G, Ramirez R, Levine FM. The homework problem checklist: Assessing children’s homework difficulties. Behavioral Assessment 1987 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins M, Pelham W, Licht M. A comparison of objective classroom measures and teacher ratings of attention deficit disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1985;13:155–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00918379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresi W, Katusic S, Colligan R, Weaver A, Jacobsen S. Long-term school outcomes for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based perspective. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:265–273. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811ff87d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R, Anastopoulos A, Guevremont D, Fletcher K. Adolescents with ADHD: Patterns of behavioral adjustment, academic functioning, and treatment utilization. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:752–761. doi: 10.1016/s0890-8567(10)80010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Edwards G, Laneri M, Fletcher K, Metevia L. Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2001;29:541–556. doi: 10.1023/a:1012233310098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:279–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:192–202. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Graham S. The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development. 2009;80:356–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady CE, Evans SW, Berlin KS, Bunford N, Kern L. Evaluating School Impairment with Adolescents Using the Classroom Performance Survey. School Psychology Review. 2012;41:429–446. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Increasing Prevalence of Parent-Reported Attention- Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among Children- United States, 2003 and 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:1439–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Lindsay JJ, Nye B. Homework in the home: How student, family, and parenting-style differences relate to the homework process. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2000;25:464–487. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment Research & Evaluation. 2005;7:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Pervasive and situational hyperactivity—confounding effect of informant: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:367–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ. Parent and teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms: psychometric properties in a community-based sample. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 1991;20:245–253. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Rapport MD, Perriello LM. Teacher ratings of academic skills: The development of the Academic Performance Rating Scale. School Psychology Review. 1991;20:284–300. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale—IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J. Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Brady CE, Harrison JR, Bunford N, Kern L, State T, Andrews C. Measuring ADHD and ODD Symptoms and Impairment Using High School Teachers’ Ratings. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:197–207. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.738456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Allen J, Moore S, Strauss V. Measuring symptoms and functioning of youth with ADHD in middle schools. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:695– 706. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Serpell ZN, Schultz BK, Pastor DA. Cumulative benefits of secondary school-based treatment of students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Review. 2007;36:256–273. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Schultz BK, DeMars CE, Davis H. Effectiveness of the Challenging Horizons after-school program for young adolescents with ADHD. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, et al. A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the Impairment Rating Scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:369–385. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Barkley RA, Fletcher KE, Smallish L. The stability of dimensions of behavior in ADHD and normal children over an 8-year followup. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:315–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00917537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Test review behavior rating inventory of executive function. Child Neuropsychology. 2000;6:235–238. doi: 10.1076/chin.6.3.235.3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF. Normative data on revised Conners parent and teacher rating scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:221–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00919127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent KM, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Sibley MH, Waschbusch DA, Yu J, et al. The academic experience of male high school students with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:451–462. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9472-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Epstein JN, Altaye M, Molina BS, Arnold LE, Vitiello B. The transition to middle school is associated with changes in the developmental trajectory of ADHD symptomatology in young adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:651–663. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Molina BS, Arnold LE, Epstein JN, Altaye M, Hinshaw SP, Hechtman L. Patterns and predictors of adolescent academic achievement and performance in a sample of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:519–531. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Dvorsky MR, Evans SW. What Specific Facets of Executive Function are Associated with Academic Functioning in Youth with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9750-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Epstein JN, Becker SP, Girio-Herrera E, Vaughn AJ. Evaluation of the homework, organization, and planning skills (HOPS) intervention for middle school students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as implemented by school mental health providers. School Psychology Review. 2012;41:342–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Hinshaw SP. Predictors of adolescent functioning in girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): the role of childhood ADHD, conduct problems, and peer status. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:356–368. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB. Revised and Expanded from “Case Study Research in Education”. Jossey-Bass Publishers; 350 Sansome St, San Francisco, CA 94104: 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K, Kelley ML. Improving homework in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Self vs. parent monitoring of homework behavior and study skills. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2007;29:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Hinshaw SP. Does childhood executive function predict adolescent functional outcomes in girls with ADHD? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:315–326. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9369-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsis EM, McKay KE, Schulz KP, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. Parent–Teacher Concordance for DSM-IV Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in a Clinic-Referred Sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:308–313. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina B, Hinshaw S, Swanson J, Arnold L, Vitiello B, Jensen P, et al. The MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:484–500. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Múthen LK, Múthen BO. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. Los Angeles, CA: Múthen & Múthen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe RG. Improved confidence intervals for the difference between binomial proportions based on paired data. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:2635–2650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham W, Gnagy E, Greenslade K, Milich R. Teacher ratings of DSM-III--R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:210–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Fabiano GA, Massetti GM. Evidence-based assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:449–476. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Smith BH, Evans SW, Bukstein O, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Sibley MH. The Effectiveness of Short-and Long-Acting Stimulant Medications for Adolescents With ADHD in a Naturalistic Secondary School Setting. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1087054712474688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillow DR, Pelham WE, Hoza B, Molina BSG, Stultz CH. Confirmatory factor analyses examining attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and other childhood disruptive behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:293–309. doi: 10.1023/a:1022658618368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior assessment system for children. 2. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robin AL. ADHD in Adolescents: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachar R, Rutter M, Smith A. The characteristics of situationally and pervasively hyperactive children: Implications for syndrome definition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1981;22:375–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1981.tb00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan M, Schwab-Stone M. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from pervious versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro ES. Academic skills problems: Direct assessment and intervention. Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Waschbusch DA, Garefino A, Kuriyan AB, Babinski DE, Karch KM. Diagnosing ADHD in Adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:139–150. doi: 10.1037/a0026577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Derefinko KD, Kuriyan AB, Sanchez F, Graziano PA. A Pilot Trial of Supporting Teens’ Academic Needs Daily (STAND): A parent-adolescent collaborative intervention for ADHD. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2013;35:436–449. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology. 2001;2:55–87. [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Fava JL. Affects of variable and subject sampling on factor pattern recovery. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:231. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-II (WASI-II) San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Individual Achievement Tests. 3. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2011b. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss G, Hechtman L. Hyperactive Children Grown Up. 2. New York: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Lambert EW, Bickman L, Simmons T, Doffing MA, Worley KA. Assessing the impact of parent and teacher agreement on diagnosing attention- deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25:41–47. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Wibbelsman CJ, Brown TE, Evans SW, Gotlieb EM, Knight JR, et al. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder among adolescents: A review of the diagnosis, treatment, and clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1734–1746. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]