Abstract

Members of the tachykinin family have trophic effects on developing neurons. The tachykinin neurokinin 3 receptor (NK3R) appears early in embryonic development; during the peak birthdates of hypothalamic neurons, but its involvement in neural development has not been examined. To address its possible role, immortalized embryonic hypothalamic neurons (CLU209) were treated with CellMask, a plasma membrane stain, or the membranes were imaged in CLU209 cells that were transfected with a pEGFP-NK3R expression vector. Non transfected cells and transfected cells were then treated with senktide, a NK3R agonist, or Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) and time-lapse confocal images were captured for the following 30 min. Compared to DMEM, senktide treatment led to filopodia initiation from the soma of both non transfected and transfected CLU209 cells. These filopodia had diameters and lengths of approximately 200 nm and 3 μm, respectively. Pretreatment with an IP3 receptor blocker, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), prevented the senktide-induced growth in filopodia; demonstrating that NK3R-induced outgrowth of filopodia likely involves the release of intracellular calcium. Exposure of transfected CLU209 cells to senktide for 24 h led to further growth of filopodia and processes that extended 10–20 μm. A mathematical model, composed of a linear and population model was developed to account for the dynamics of filopodia growth during a timescale of minutes. The results suggest that the ligand-induced activation of NK3R affects early developmental processes by initiating filopodia formation that are a prerequisite for neuritogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

During development, the extension of plasma membrane protrusions serve roles in a number of cellular processes, including neurite outgrowth, chemotaxis, growth cone extension, and cell migration. These cellular extensions that protrude from the cell surface include the broad, flat lamellipodia, and hair-like, thin (0.1–0.3 um dia) extensions in the form of filopodia. Filopodia are being defined as any thin process that extends beyond the cell surface (Yang and Svitkina, 2011). Filopodia serve a variety of functions that span the developmental state of the cell and that reflect the association of the filopodia with cell specific cell structures (i.e. growth cones, dendrites, soma, axons). Filopodia serve a sensory function and they orient in the direction of chemotaxic cues in the extracellular environment (Bentley and Toroian-Raymond, 1986; Zheng et al., 1996). Also, the outgrowth of filopodia is fundamental for the development of larger processes and is an initial event leading to the formation of neurites in embryonic neurons (Dent et al., 2007). Furthermore, embryonic neurons that are mutated and lack filopodia do not elaborate neurites (Dent et al., 2007).

Local, extracellular cues stimulate the extension of filopodia and the development of neurites. Moreover, a number of neurochemicals that serve traditional roles in neurotransmission are cues that lead to the initiation and growth of filopodia in both the developing and mature nervous systems (Maletic-Savatic et al., 1999; Heiman and Shaham, 2010). For example, filopodia outgrowth is seen within 15 min of application of glutamate to embryonic hippocampal neurons while longer application of glutamate receptor agonists enhance neurite outgrowth (Joseph et al., 2011; Henle et al., 2012). Similarly, acetylcholine and serotonin cause short-latency extension of filopodia and an increased neurite outgrowth from neurons (Fricker et al., 2005; Yoshida et al., 2011; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012; Zhong et al., 2013).

In addition, the tachykinins are shown to have neurotrophic actions. Application of substance P (SP) promotes the short-latency (within 10 min) outgrowth of processes, what the authors referred to as neurites, from embryonic neurons (Narumi and Fujita, 1978). Furthermore, when rat chromaffin cells are exposed to SP analogues the cells exhibit neurite outgrowth and adopt a sympathetic neuronal phenotype (Barker et al., 1993). A related tachykinin family member is neurokinin B that binds preferentially to the neurokinin 3 receptor (NK3R)(Lavielle et al., 1988). The role of this tachykinin in filopodia and neurite outgrowth has not been examined, but several factors suggest that it too may have neurotrophic actions. First, NK3R appear as early as embryonic day 6 in the cortex (Dam et al., 1988), while in the hypothalamus, NK3R appears later at E12–E13 (Brischoux et al., 2002). Second, exposing embryonic hypothalamic neurons to senktide, a NK3R agonist, leads to the upregulation of Bcl-2 and regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS2) (Thakar et al., 2012). Bcl-2 gene expression appears early in embryonic brain development (Merry et al., 1994) and Bcl-2 expression is associated with neurite outgrowth from neuronal cells (Oh et al., 1996; Eom et al., 2004). Also, senktide up-regulated RGS2 expression and other reports show that RGS2 is localized to newly formed neurites (Heo et al., 2006). The early developmental appearance of the NK3 receptor, its association with the induction of neurite growth-associated genes, and that other tachykinins have neurotrophic effects suggest that NK3R may also have trophic actions and modify the cytoskeletal structure.

We investigated the effects of a NK3R agonist, senktide, on the initiation and extension of filopodia in immortalized, embryonic hypothalamic cells and embryonic cells that were transfected with a pEGFP-NK3R expression vector. Senktide or media was added to the wells and the cells were imaged for the following 30 min. During this time, senktide caused an increase in filopodia outgrowth. NK3R works through the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) pathway (Mizuta et al., 2008) and intracellular calcium affects neurite outgrowth through the stabilization of actin filaments in growing neurites (Lankford and Letourneau, 1989). This relationship led to the hypothesis that that filopodia outgrowth may be a calcium-dependent process and that was confirmed by the finding that incubating cells in an IP3 receptor blocker, 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), prior to senktide treatment prevented the initiation and outgrowth of filopodia.

METHODS

Cell Culture

CLU209 cells were purchased from Cedarlane (Ontario, Canada). CLU209 cells are a rat immortalized neuronal hypothalamic cell line collected on embryonic day 18. This cell line was previously characterized and shown to express the NK3R. Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 25mM dextrose, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. CLU209 cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and were grown as a monolayer in a T-75 flask. When the cells were ~80% confluent they were split at a 1:30 ratio by trypsinization to get single cells in suspension. Cells were generally passed every 3 days.

Membrane labeling of CLU209 cells

The plasma membrane of embryonic neurons was made visible using a membrane stain. CLU209 cells (5.4 × 104) were plated on a 35 mm glass bottom dish (P35G-1.0-14-C, MatTek, Ashland, MA) with 1.5 ml of DMEM. On the day of the experiment, Cellmask Orange Plasma Membrane Stain (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA; 2.0 μg/ml) was added to each well containing 1.5 ml of DMEM and left for 10 min. Cells were then rinsed extensively (~10 rinses) using phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and then 1.5 ml of DMEM was added to each well.

Plasmid Extraction and CLU209 transfection

Cells (5.4 × 104) were plated on a 35 mm glass bottom dish (P35G-1.0-14-C, MatTek, Ashland, MA) with 1.5 ml of DMEM. CLU209 cells were transfected with a pEGFP-NK3R expression vector (kindly provided by Dr. Nigel Bunnett). The pEGFP-NK3R vector was grown in One Shot Top-10 competent E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The plasmid was then extracted using a QIAGEN© Plasmid Midi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA purity was >1.8 as determined by spectrophotometric 260/280 nm ratio (NanoDrop 2000c, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). The plasmid was stored at −20°C. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used for the transfections following the protocols provided. The pEGFP-NK3R plasmid (1.6 μg) was mixed in 100 μl of DMEM and incubated for 5 min. In a separate tube 3.2 μl of lipofectamine 2000 was added to 100 μl of DMEM, incubated for 5 min, and then added to the tube containing the DNA. The lipofectamine/DNA mixture was left at room temperature for 20 min and then added to the DMEM bathing the CLU209 cells. CLU209 cells were incubated at 37° C overnight with the lipofectamine/DNA complex. Media was changed the next morning and 2 days after the transfection geneticine (600 μg/ml) was added. The transfection efficiency was about 5–10% of the cells per plate.

PCR

Expression levels of NK3R were determined in CLU209 cells and transfected cells. In addition, NK3R are expressed in the rat brain paraventricular (PVN) and supraoptic (SON) hypothalamic nuclei (Ding et al., 1996; Jensen et al., 2008). These two brain areas were dissected from a male Charles River Laboratory rat and run with the CLU209 samples. Cells were lysed using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and the RNA was isolated. Expression of NK3R was confirmed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using the Superscript III 1-step RT-PCR system with platinum Taq DNA Polymerase from Invitrogen. The Tacr3 specific PCR primer set was purchased from SABioscience (PPR06842A; Valencia, CA, USA). In order to normalize the NK3R expression, samples were also amplified for control housekeeping gene β-actin (PPR06570B from SABioscience). The cDNA was subjected to rapid amplification after the reverse-transcription. The cDNA was denatured at 94°C for two minutes, followed by 40 cycles of amplification of the specified sequence, with a final extension of 5 minutes at 68°C. The amplified sequence was then characterized by a spectrophotometer NanoDrop 2000c and the concentration of the amplified gene was recorded in (μg/μl).

The RT-PCR product was visualized using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, with florescent tag ethidium bromide. Wells were loaded with the amplification product from the transfected and non-transfected cell lines, PVN and SON tissue for NK3R and actin. Benchtop PCR Marker (G753A from Promega, Madison, WI) was loaded for base pair reference. The gel was run at 110 Volts for 45 minutes, after which the gel was imaged using UV illumination and the QuantityOne software program. Relative intensities of the bands were calculated, normalized and compared.

Acute effects of senktide on filopodia growth

CellMask membrane-labeled and transfected cells were imaged using a Zeiss 710 LSM confocal microscopy system with a 63 x objective. Once a fluorescent cell was identified, the upper and lower limits of the cell were measured and the pinhole was then adjusted to match the thickness of the cell. While confocality was compromised, setting the pinhole in this manner maximized the visualization of filopodia and their movement and minimized the likelihood that the process would go out of focus. The fluorescent cell from each well was then imaged for approximately 40 min. During the baseline, cells incubated in 1.5 ml of DMEM and baseline images were captured every 30 sec for 5–10 min. Then either DMEM (75 μl) or senktide (75 μl, 0.02 mM,) was added to the wells for a final concentration of 1 μM. Images continued to be captured every 30 sec and the time lapse images were then compiled into an image sequence. From this time lapse series, the images obtained at 5 min, 12 min, 20 min, and 30 min post treatment were isolated for further analysis. Neurite length and the number of filopodia were quantified using the semiautomatic neurite tracing program of NeuronJ (National Institutes of Health). In addition, the reliability of the scoring was established by having two investigators independently quantify the length and the number of filopodia of a sample of cells (n=7). Independent analysis was found to be very comparable between the investigators, and when compared to the data generated using NeuronJ (r’s>0.9).

The lengths of the filopodia were measured to the nearest 0.1 μm. In order for the process to be included in the data set, the process had to be in the focal plane during the course of the experiment. That is, the filopodia had to be visible and traceable in each of the successive 30 sec time lapse images. Since, the pinhole was opened to match the upper and lower boundary of the cell, the vast majority of filopodia could be tracked or seen throughout the experiment. Filopodia that went out of focus or could not be tracked for the duration of the experiment were removed from the data set. This procedure ensured that measurements of filopodia at 5 min, 12 min, 20 min and 30 min were obtained from the same identified filopodium during the course of the experiment.

During the baseline period, the number and length of each of the processes was determined. A template of the cell and its protrusions was developed and used for the analysis of the cell at the successive time points. Filopodia were identified by letters and monitored from frame to frame in the time lapse series. In this way, individual processes could be reliably identified during the experiment and cell protrusions that were not on the previous template could be identified and labeled as a new process. The changes in neurite length from the previous time point to the next were calculated.

IP3 Blocker

CLU209 cells were first transfected (procedure described above). A 2 (pretreatment) x 2 (treatment) design was used to test whether neurite initiation and growth in response to senktide was mediated by intracellular calcium. The role of intracellular calcium was tested using the IP3 blocker (2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, 2-APB [Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK]). The four test conditions were: 2-APB pretreatment and senktide (n=7), 2-APB pretreatment and DMEM (n=5), DMEM pre-treatment and senktide (n=5), and DMEM pre-treatment and DMEM (n=4). Baseline images were collected and then DMEM or 2-APB was added to the cells. The IP3 blocker (15 μL, 10 mM) was added to the plated cells in 1.5 ml of DMEM for a final concentration of 100 μM. Ten min later DMEM or senktide was added to the plated cells (final concentration of 1 μM) to the wells. Images were then captured for the following 30 min.

24 hour exposure to senktide

The same transfection procedure was followed and after identifying the transfected cells, senktide (final concentration 1 μm) or DMEM was added to the wells and the cells were returned to the CO2 incubator. Twenty four hours later, cells were removed from the incubator and a single confocal image was captured.

There was extensive outgrowth of processes and images were quantified using a grid system based on a modified ImageJ Grid plugin. The soma was outlined and superimposed on the cell. This soma membrane map was then expanded outward in 3 μm steps until all of the processes terminated within the final contour ring. The number of processes terminating in each contour ring was counted. The number of processes falling within each range was then compared between senktide and DMEM (control) cells.

Statistical analysis

The number of filopodia and their lengths were compared using t-tests and 2-way (treatment x time) mixed ANOVAs using SPSS Statistical program. In addition, Bonferroni’s t-test was used for multiple comparisons.

Model Development

A standard exponential population model equation: , was used to model the growth in number of filopodia in transfected cells exposed to senktide and DMEM. In the model, P = b * ect, b is a model parameter, c is the growth rate and t is the time. To define b and c with respect to the experimental data being modeled, these parameters are extracted through the manipulation of the equation in the more usable linear form, y = mx + j, as shown below.

The final equation has put P = b * ect in the desired linear form of y = mx+j, where y = ln(P), m = c, x = t, j = ln (b). Using this form, the experimental data can be linearly plotted against time, allowing parameters b and c to be extracted from the y-intercept and the slope of the line, respectively. Note that the parameter b is obtained from the y-intercept j by

The parameters b and c, obtained from above, are then substituted into the original equation, P = b * ect to complete the model. The exponential population model P = b * ect however, only effectively models the number of new filopodia after the addition of senktide. Since each experimental plate consisted of two distinct environments, a baseline growth and a post-treatment (senktide or DMEM) growth, a single model to cover both of these time frames would promote error in the model. To reduce error in the model, the baseline growth was modeled separately as a linear growth of filopodia. Therefore, to accurately reflect both of these growth environments, the model is a piecewise function, with specific conditions for baseline or post-treatment filopodia growth. The use of a piecewise function, composed of a linear model P = mt + j and the population model P = b * ect, reduces error in the model data. This piecewise function is written as: .

The two parameters, m and t in the linear model for baseline growth, were derived independently from the parameters for the population growth function. This was done by graphing the baseline values and applying a line of best fit. From this line of best fit the slope and y-intercept (parameters m and j respectfully) were extracted and used in the above linear equation for the t=baseline condition only.

RESULTS

PCR analysis of NK3R in transfected and non-transfected cells

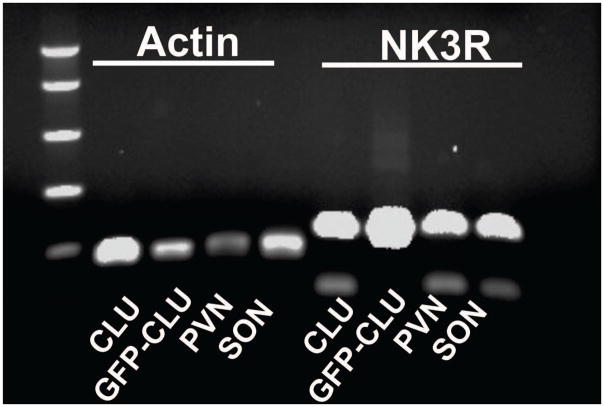

The estimated size of NK3R was 177 bp and transfected cells, non-transfected cells, PVN, and SON had bands slightly higher (~190 bps) than the estimated size (Figure 1). Similarly the actin bands were slightly higher (~158 bp) than estimated (127 bp) in all of the samples. Normalizing the expression of NK3R bands to the house keeping gene β-actin, gave density values of 0.75 for transfected cells and 0.43 for the non-transfected cells. As such, transfection resulted in a ~1.7 fold increase in the expression of NK3R over that seen in non-transfected cells.

Figure 1.

Detection of NK3R and actin by PCR. PCR products had the appropriate size on ethidium bromide stained agrose gels: actin= 127bp; NK3R= 177bp. CLU= non transfected cells; GFP-CLU= pEGFP-NK3R transfected cells; PVN= rat paraventricular nucleus; SON= rat supraoptic nucleus. Transfected CLU209 cells expressed 1.7 times more NK3R than did non transfected cells.

NK3R agonist promotes the appearance of new filopodia and increases the length of filopodia in embryonic neurons

Non transfected cells

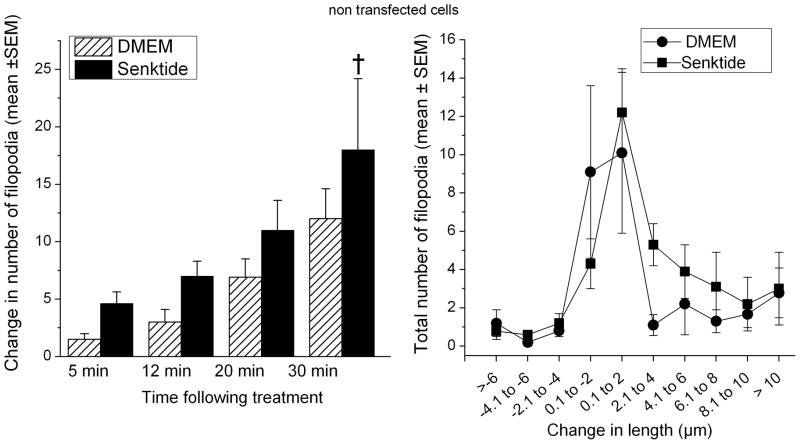

Filopodia were quantified following the application of senktide (n=8 cells) or DMEM (n=10 cells). A total of 333 and 304 filopodia were quantified in the senktide (range 19 to 124 per cell) and DMEM (range 19–83 per cell) conditions, respectively. As shown in Figure 2 (left panel), senktide caused an increase in the outgrowth of filopodia compared to DMEM. Analysis of variance showed that filopodia outgrowth increased over time in both treatment conditions, but that the growth of filopodia was significantly greater in the senktide condition, F (3,51)= 10.8, p<0.0001.

Figure 2.

Non transfected cells. Left panel: The change in number reflects the appearance of new filopodia after the application of DMEM or senktide to the wells. Senktide treatment accelerated the outgrowth of new filopodia compared to DMEM, † p<0.0001. Right panel: Filopodia were sorted into 2 μm bins based on the change in their length from the baseline compared to their length at the end of the experiment (30 min post treatment).

The length change of the filopodia from baseline to the conclusion of the experiment was determined (Figure 2, right panel). The changes in length from baseline were sorted into 2 μm bins. Overall, filopodia extended and retracted most frequently ~2 μm in both treatment groups. Senktide caused a greater number of filopodia to extend ~4 μm than did DMEM (p<0.04).

Transfected cells

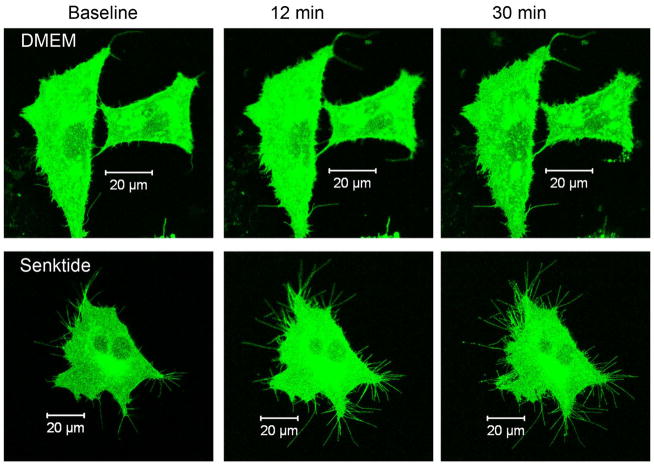

Filopodia were measured in senktide treated cells (n=12) and DMEM treated cells (n=9). The pinhole was set to the thickness of the cell (range 412–530 um) and filopodia were randomly selected for each cell and their diameter measured. The diameters of the filopodia were similar in the senktide and DMEM treatment conditions (237 ± 0.009 μm, 249 ± 0.009 μm, respectively [p=0.4]). Administration of senktide induced substantial morphological changes with respect to the number of filopodia. Figure 3 shows images of a DMEM and senktide treated cell at baseline and 12 and 30 min following treatment.

Figure 3.

Images of NK3R-GFP transfected cells prior to (baseline), 12 min and 30 min following the administration of DMEM (upper panels) or senktide (lower panels). In order to show the fine processes in the brightness of the images was increased similarly for the DMEM and senktide treated cells using Photoshop.

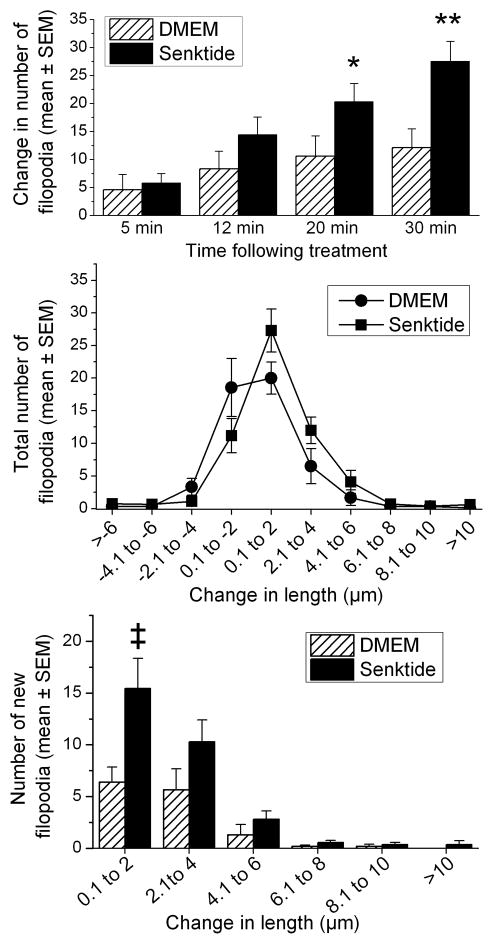

During the 30 min following the treatments, there was a significant increase in the number of filopodia in both the DMEM and senktide treated cells, F(3,57)= 38.1, p<0.001 (Figure 4, upper panel). While initially (5 min) both treatments were associated with a similar change in the number of filopodia, the subsequent increase in the number of filopodia was not similar in the two groups. During the remainder of the experiment, senktide resulted in a significant increase in the number of filopodia over that seen in the DMEM cells, F (3,57)= 7.1, p<0.001. Further comparisons showed that there were more filopodia 20 min (p<0.06) and 30 min (p<0.01) following senktide compared to DMEM.

Figure 4.

Transfected cells. Upper panel: Shown is the change in the number of filopodia from baseline following DMEM or senktide. Senktide treatment increased the number of filopodia compared to DMEM at 20 and 30 min, *p<0.06, ** p<0.01. Middle panel: The change in length (increase and decrease) of the filopodia that were measured from the baseline to the end of the experiment (30 min post treatment) is shown. Lower panel: The number of new filopodia that appeared following the administration of senktide or DMEM is plotted as a function of length. Length was divided into 2 μm bins, ‡p<0.009 compared to DMEM.

The length of each of the filopodia during baseline was subtracted from the final length of the filopodium at the end of the experiment. The changes in length were sorted into 2 μm bins. A decrease in the length of the filopodia is reflected in the bins with negative length changes and those showing increases in length are in the positive bins. As shown in Figure 4 (middle panel), during the experiment there were dynamic changes in the filopodia with some filopodia decreasing in length in both treatment groups. The pattern of length changes is similar to that observed in the non-transfected cells with filopodia most frequently retracting ~2 μm in both treatment groups. In terms of filopodia extension, more filopodia extended up to 4 μm in senktide treated cells than in DMEM treated cells.

New filopodia that appeared after senktide or DMEM were identified and their length at the end of the experiment was determined. The change in lengths of newly formed filopodia is shown in Figure 4 (lower panel). These filopodia were not present during baseline and were assigned a starting length of zero and as such, their length only increased. Filopodia identified on DMEM and senktide-treated cells were sorted into one of six length categories or bins: 0.1–2, >2.1 to 4, >4.1 to 6, >6.1 to 8, >8.1 to 10, and >10 μm. In both DMEM and senktide treated cells, the ending length of the majority of the newly formed filopodia was up to 4 μm in length. Analysis of the number of filopodia showed a treatment effect, F(1,18)= 10.4, p<0.005, and a significant interaction of treatment x length category, F(5,90)= 3.3, p<0.009.

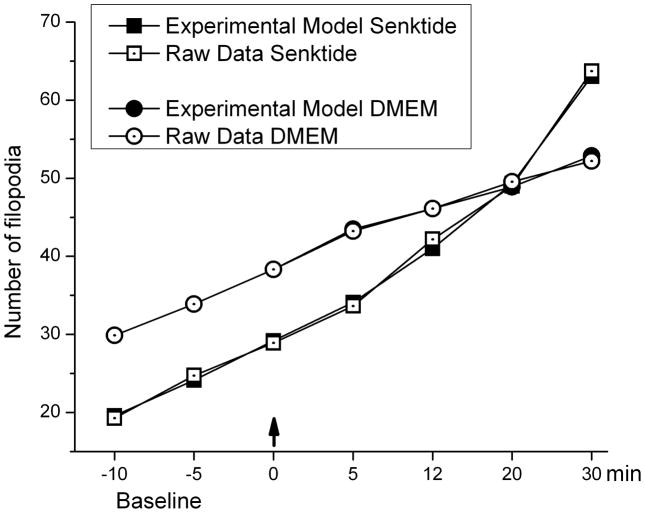

Piecewise function accurately models the actions of senktide on filopodia outgrowth in transfected embryonic neurons

The piecewise function accurately models new filopodia growth in senktide treated cells (Figure 5). The model is used with several key time intervals (3 during baseline, 4 during post-treatment) in order to accurately predict the number of filopodia at any desired time interval. Using the results from the average number of filopodia for all of the senktide treated cells, the piecewise function model accurately predicts the number of filopodia at a given time interval, with percent error < 3 ± 0.84 % for all time intervals chosen (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The actual number of filopodia measured during the baseline (times −10, −5, 0) and following senktide or DMEM (times 5, 12, 20, 30) and the number of filopodia predicted by the piecewise function are shown. Arrow indicates the application of senktide or DMEM to the wells. The experimental model accurately predicts the obtained data.

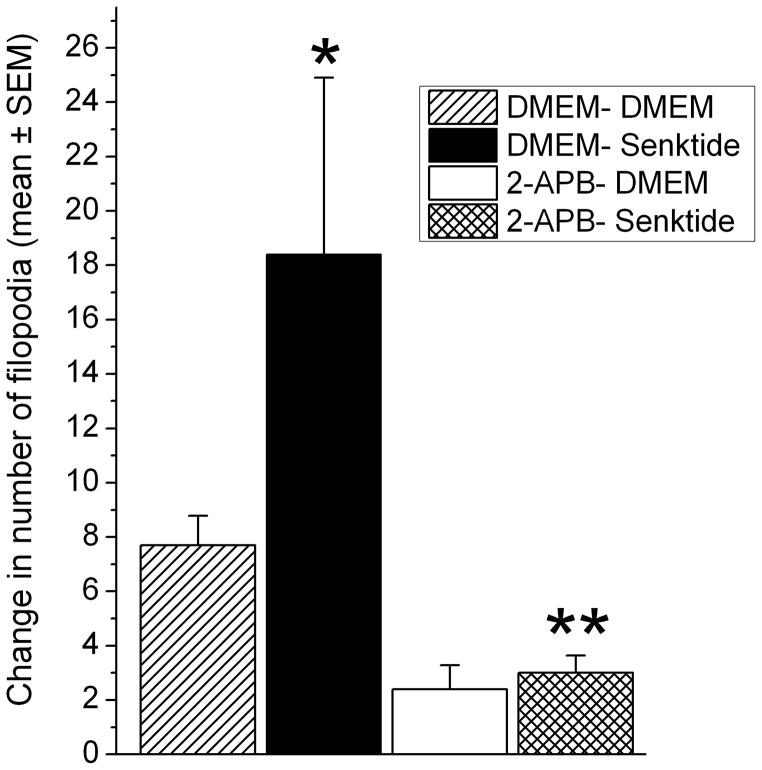

IP3 blocker blocks the effects of senktide on filopodia outgrowth

The number of filopodia present at 30 min in the DMEN-DMEN (n=4; 17–32 filopodia/cell), DMEN-Senktide (n=5; 22–130 filopodia/cell), 2-APB-DMEM (n=5; 27–35 filopodia/cell) and 2-APB-Senktide (n=7; 13–49 filopodia/cell) groups was expressed as a change from baseline. Senktide stimulated the appearance of new filopodia and at 30 min following the treatments there were more filopodia in cells pretreated with DMEM- senktide than in cells that were administered DMEM- DMEM, p<0.06 (Figure 6). This outgrowth of filopodia in response to senktide was intracellular calcium-dependent because pretreatment with 2-APB prior to senktide blocked the appearance of new filopodia. There were significantly fewer filopodia in the APB-senktide condition than in the DMEM-senktide condition, p<0.006, and the APB-DMEM and APB-senktide conditions were not different, p<0.3. It appears in Figure 6 that APB pretreatment in the DMEM condition reduced the number of filopodia compared to the DMEM-DMEM condition, but this was not significant, p<0.3.

Figure 6.

Treatment with senktide (DMEM-Senktide) stimulated the growth of filopodia compared to DMEM-DMEM, *p<0.06. There were significantly fewer filopodia in the APB-senktide condition than in the DMEM-senktide condition, **p<0.006. Also, the number of filopodia in the APB-DMEM and APB-senktide conditions were not different, p<0.3.

24 hour exposure to senktide

A total of 550 filopodia were identified on five senktide-treated cells (range 30–184 filopodia per cell) and 122 processes were identified on four DMEM-treated cells (range 13–41 filopodia per cell) (Figure 7). As in the acute exposure, filopodia were sampled from each cell and the diameter of the filopodia (~0.2 μm) was similar for the DMEM and senktide-treated cells. Analysis indicated that senktide stimulated the appearance of filopodia compared to DMEM, t(7)= 2.4, p<0.05 (Figure 7, left panel). The number of filopodia appearing after the administration of senktide or DMEM is expressed as a function of lengths and is shown in Figure 7 (right panel). Analysis of the number of filopodia in the different length categories showed a significant effect of senktide, F(1,48)= 5.3, p<0.02. The interaction of treatment x length reflects that senktide facilitated the growth of processes up to approximately 27 μm in length, F(6,48)= 2.3, p<0.05. The majority of filopodia in the DMEM condition were less than 9 μm in length, while in the senktide condition it was frequent for filopodia to reach lengths of up to 27 μm. Relatively few processes longer than 27 μm were present in either treatment condition (Figure 7, right panel).

Figure 7.

24 h exposure. The left panel shows the total number of filopodia radiating from the transfected cells exposed to senktide or DMEM for 24 h. The number of filopodia was significantly greater in the senktide-treated cells than in the DMEM-treated cells, *p<0.05. The number of filopodia that appeared following the administration of senktide or DMEM is plotted as a function of length (right panel, **p<0.02 compared to DMEM). Overall, the longer incubation in senktide led to the growth of longer processes than what was observed during the acute (30 min) exposure to senktide (shown in Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Tachykinin peptides, specifically substance P acting at its receptor, affect neuron differentiation and promote neurite outgrowth (Narumi and Maki, 1978; Barker et al., 1993) and a second tachykinin, neurokinin A, promotes tissue cell growth (Nilsson et al., 1985). The possible involvement of the tachykinin, neurokinin B (NKB) and the NK3 receptor in developmental processes had not been examined, even though NK3R appear as early as E12-E13 in diencephalic brain regions and during the immediate postnatal period in other regions (Brischoux et al., 2001; Brischoux et al., 2002). While the ontogeny of the NK3R has been somewhat studied, all that is known about the hypothalamic ontogeny of the NKB is that it is present at birth; earlier time points were not studied (Diez-Guerra et al., 1989). The early appearance of the NK3R suggests a possible developmental role of this receptor.

To study the involvement of NK3R in developmental processes, embryonic hypothalamic neurons and embryonic hypothalamic cells that were transfected to over-express the NK3R were treated with a NK3R agonist, senktide, or DMEM. The data presented here show for the first time that in addition to NK3R functioning in synaptic signaling in the hypothalamus of the mature brain (Haley and Flynn, 2006; Jensen et al., 2008) the activation of NK3R promotes a short latency increase in the appearance of new filopodia in CLU209 cells and CLU209 cells that were transfected to over-express NK3R. Similar to what has been described in dorsal root ganglion cells (Obata and Inoue, 1982), there was a rapid appearance of filopodia around the entire cell surface. These filopodia shared a common diameter of approximately 0.2 μm and few filopodia were longer than ~5 μm in both treatment conditions. The temporal pattern of filopodia outgrowth following senktide was similar in both groups of cells. One difference was that over-expression of NK3R led to a greater increase in the number of filopodia. In comparing the graphs of the total number of filopodia, there were ~2x as many filopodia in transfected cells then in the non-transfected cells.

The role of Ca++in mediating theoutgrowth of filopodia during the acute and prolonged exposure to senktide was investigated. In our experiments, cells were incubated in DMEM that lacks calcium and as such, any involvement of Ca++ would need to be from intracellular stores. NK3R activates phospholipase Cβ (PLC) via Gq coupling, resulting in D-myo-inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) synthesis and increased intracellular Ca++ concentration (Nakajima et al., 1992; Khawaja and Rogers, 1996; Mizuta et al., 2008). Moreover, the increase in IP3 synthesis and intracellular Ca++ appears within 1–2 minutes of applying the NK3R agonist (Nakajima et al., 1992; Mizuta et al., 2008). A number of studies show that IP3 signaling and intracellular calcium regulates neurite growth. For example, filopodia extension is observed within 10 min of a rise in intracellular Ca++ (Rehder and Kater, 1992). Also, depleting intracellular Ca++ or inhibiting IP3 signaling by administering IP3 receptor blockers, such as 2-APB, suppress neurite outgrowth in neurons (Takei et al., 1998; Ramakers et al., 2001; Iketani et al., 2009). Because NK3R is linked to IP3 and intracellular Ca++ signaling, we examined if inhibiting IP3R signaling would block the outgrowth of filopodia in response to senktide. We show that pretreatment with the IP3 receptor antagonist, 2-APB (Mizuta et al., 2008), prevented the senktide-induced outgrowth of filopodia. Furthermore, the outgrowth of filopodia that is stimulated by other neurotrophic factors, such as brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), required the polymerization of actin fibers (Gibney and Zheng, 2003). IP3 formation and the release of intracellular Ca++ stimulates actin polymerization (Europe-Finner and Newell, 1986). As such, the activation of NK3R triggers downstream signaling through the IP3 pathway to stimulate the growth of filopodia and the morphological alteration of the embryonic neuron. Our results indicate that the immediate growth effects of senktide on filopodia likely involves the release of intracellular calcium.

Incubation in senktide for 24 hours caused a greater outgrowth of filopodia. There were roughly four times more new filopodia on cells exposed to senktide for 24 h compared to the acute, 30 min exposure. In addition, exposure to senktide for 24 h resulted in the filopodia reaching longer lengths than with the acute senktide exposure. Whereas few filopodia extended more than 5 μm in the acute experiment, filopodia reached lengths of over 20 μm when exposed to senktide for 24 h. While length was affected by the longer exposure to senktide, the diameter of the filopodia (0.2 μm) was the same as that measured following the acute exposure to senktide. During the longer incubation, other downstream signaling pathways may be recruited by senktide that promote neurite outgrowth. Previously, we reported that incubating CLU209 cells in senktide led to the upregulation of several genes, including BCL2 and RGS2 (Thakar et al., 2012), that are reported to be involved in neural development and neurite outgrowth. For example, BCL2 is widely expressed in neurons early in development (Merry et al., 1994) and over-expression of BCL2 in neural cell lines promotes neurite growth (Oh et al., 1996; Eom et al., 2004). Similarly, senktide up-regulated regulator of g protein signaling 2 (RGS2) and transient over-expression of RGS2 enhances neurite outgrowth in an adrenal cell line (Heo et al., 2006). Conversely, knock-down of RGS2 expression using siRNA reduces neurite outgrowth (Heo et al., 2006). As indicated, senktide treatment led to the increased expression of these two genes (Thakar et al., 2012) and as such, their upregulation may contribute to the appearance of processes in the 24 h treated cells. In addition to these gene targets, other mechanisms may be recruited during the 24 hour exposure to senktide. For example, the rise in intracellular calcium may lead to the activation of Ca++ sensitive proteins like gelsolin, myosin kinase (Bennett and Weeds, 1986) and calpain (Gitler and Spira, 1998) that contribute to cytoskeleton growth. Also, Ca++ stimulated activation of Cam Kinase II affects the cytoskeleton via phosphorylation of neurofilament proteins (Bui et al., 2003; Vallano et al., 1985).

Several studies have provided mathematical models to describe neurite initiation, differentiation of processes to dendrites or axons, and axon trajectory (Graham and van Ooyen, 2006). One aspect that is unique in our analysis is the time course where changes in filopodia were measured immediately after the application of the potential trophic factor. A mathematical model to describe the effects of senktide on the growth in the number of filopodia was developed. The experimental model was compared to the actual number of filopodia following senktide and in the DMEM conditions. In this model, the growth in the number of new filopodia following application of senktide was described by a population growth function. The piecewise function used to model the DMEM and senktide treated cells consists of two distinct functions. The first models the baseline growth of filopodia for the cell (pre-treatment) while the second models the effect of treatment on filopodia growth (post-treatment). This single model was applied to both the DMEM and senktide treated cell data. The baseline function of the piecewise model produced near identical slopes for both DMEM and senktide data, indicating that during the baseline period all of the cells were governed by the same process controlling filopodia growth. However, the post-treatment function of the piecewise model was unique for each of the two different treatment groups. The post-treatment function slope for DMEM behaved analogously to the slope of the baseline function, while the slope for the senktide post-treatment function was dissimilar to the baseline function with a sharp increase in the rate of filopodia growth. The expression of NK3R on soma and extending processes leads to a feed forward system whereby activation of NK3R by senktide causes increases in the intracellular Ca++ concentration leading to the continued outgrowth of filopodia. Developmentally this may be significant because the change in filopodia development to an exponential population growth allows a significantly higher filopodia population per cell. This larger filopodia population in response to an NK3R ligand may then facilitate neuron migration and neurite development.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS57823) and from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P30 GM103398) awarded to F.W.F.

References

- Barker R, Dunnett S, Fawcett J. A selective tachykinin receptor agonist promotes differentiation but not survival of rat chromaffin cells in vitro. Exp Brain Res. 1993;92:467–472. doi: 10.1007/BF00229034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J, Weeds A. Calcium and the cytoskeleton. British Medical Bulletin. 1986;42:385–390. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D, Toroian-Raymond A. Disoriented pathfinding by pioneer neurone growth cones deprived of filopodia by cytochalasin treatment. Nature. 1986;323:712–715. doi: 10.1038/323712a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brischoux F, Cvetkovic V, Griffond B, Fellmann D, Risold PY. Time of genesis determines projection and neurokinin-3 expression patterns of diencephalic neurons containing melanin-concentrating hormone. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1672–1680. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brischoux F, Fellmann D, Risold PY. Ontogenetic development of the diencephalic MCH neurons: a hypothalamic ‘MCH area’ hypothesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1733–1744. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui CJ, Beaman-Hall CM, Vallano ML. Ca2+ and CaM kinase regulate neurofilament expression. Developmental Neuroscience. 2003;14:2073–2077. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200311140-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam TV, Escher E, Quirion R. Evidence for the existence of three classes of neurokinin receptors in brain. Differential ontogeny of neurokinin-1, neurokinin-2 and neurokinin-3 binding sites in rat cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 1988;453:372–376. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent EW, Kwiatkowski AV, Mebane LM, Philippar U, Barzik M, Rubinson DA, Gupton S, Van Veen JE, Furman C, Zhang J, Alberts AS, Mori S, Gertler FB. Filopodia are required for cortical neurite initiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1347–1359. doi: 10.1038/ncb1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Guerra FJ, Veira JAR, Augood S, Emson PC. Ontogeny of the novel tachykinins neurokinin A, neurokinin B and neuropeptide K in the rat central nervous system. Regul Pept. 1989;25:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(89)90251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YQ, Shigemoto R, Takada M, Ohishi H, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Localization of the neuromedin K receptor (NK3) in the central nervous ystems of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:290–310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960108)364:2<290::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom DS, Choi WS, Oh YJ. Bcl-2 enhances neurite extension via activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Europe-Finner GN, Newell PC. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and calcium stimulate actin polymerization in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Cell Sci. 1986;82:41–51. doi: 10.1242/jcs.82.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker AD, Rios C, Devi LA, Gomes I. Serotonin receptor activation leads to neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;138:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibney J, Zheng JQ. Cytoskeletal dynamics underlying collateral membrane protrusions induced by neurotrophins in cultured Xenopus embryonic neurons. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:393–405. doi: 10.1002/neu.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler D, Spira ME. Real time imaging of calcium-induced localized proteolytic activity after axotomy and its relation to growth cone formation. Neuron. 1998;20:1123–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham BP, van Ooyen A. Mathematical modelling and numerical simulation of the morphological development of neurons. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley GE, Flynn FW. Agonist and hypertonic saline-induced trafficking of the NK3-receptors on vasopressin neurons within the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1242–1250. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00773.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman MG, Shaham S. Twigs into branches: how a filopodium becomes a dendrite. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henle F, Dehmel M, Leemhuis J, Fischer C, Meyer DK. Role of GluN2A and GluN2B subunits in the formation of filopodia and secondary dendrites in cultured hippocampal neurons. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2012;385:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00210-011-0701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo K, Ha SH, Chae YC, Lee S, Oh YS, Kim YH, Kim SH, Kim JH, Mizoguchi A, Itoh TJ, Kwon HM, Ryu SH, Suh PG. RGS2 promotes formation of neurites by stimulating microtubule polymerization. Cell Signal. 2006;18:2182–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iketani M, Imaizumi C, Nakamura F, Jeromin A, Mikoshiba K, Goshima Y, Takei K. Regulation of neurite outgrowth mediated by neuronal calcium sensor-1 and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in nerve growth cones. Neuroscience. 2009;161:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen D, Zhang Z, Flynn FW. Trafficking of tachykinin neurokinin 3 receptor to nuclei of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus following osmotic challenge. Neuroscience. 2008;155:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph DJ, Williams DJ, MacDermott AB. Modulation of neurite outgrowth by activation of calcium-permeable kainate receptors expressed by rat nociceptive-like dorsal root ganglion neurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:818–835. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja AM, Rogers DF. Tachykinins: receptor to effector. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;28:721–738. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(96)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankford KL, Letourneau PC. Evidence that calcium may control neurite outgrowth by regulating the stability of actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1229–1243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavielle S, Chassaing G, Ploux O, Loeuillet D, Besseyre J, Julien S, Marquet A, Convert O, Beaujouan JC, Torrens Y, et al. Analysis of tachykinin binding site interactions using constrained analogues of tachykinins. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90753-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maletic-Savatic M, Malinow R, Svoboda K. Rapid dendritic morphogenesis in CA1 hippocampal dendrites induced by synaptic activity. Science. 1999;283:1923–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry DE, Veis DJ, Hickey WF, Korsmeyer SJ. bcl-2 protein expression is widespread in the developing nervous system and retained in the adult PNS. Development. 1994;120:301–311. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuta K, Gallos G, Zhu D, Mizuta F, Goubaeva F, Xu D, Panettieri RA, Jr, Yang J, Emala CW., Sr Expression and coupling of neurokinin receptor subtypes to inositol phosphate and calcium signaling pathways in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L523–534. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00328.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, Tsuchida K, Negishi M, Ito S, Nakanishi S. Direct linkage of three tachykinin receptors to stimulation of both phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis and cyclic AMP cascades in transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2437–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumi S, Fujita T. Stimulatory effects of substance P and nerve growth factor (NGF) on neurite outgrowth in embryonic chick dorsal root ganglia. Neuropharmacology. 1978;17:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(78)90176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumi S, Maki Y. Stimulatory effects of substance P on neurite extension and cyclic AMP levels in cultured neuroblastoma cells. J Neurochem. 1978;30:1321–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1978.tb10462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J, von Euler AM, Dalsgaard CJ. Stimulation of connective tissue cell growth by substance P and substance K. Nature. 1985;315:61–63. doi: 10.1038/315061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordman JC, Kabbani N. An interaction between alpha7 nicotinic receptors and a G-protein pathway complex regulates neurite growth in neural cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5502–5513. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata K, Inoue H. Development of microspikes and neurites in cultured dorsal root ganglion cells. Neurosci Lett. 1982;30:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YJ, Swarzenski BC, O’Malley KL. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in a murine dopaminergic neuronal cell line leads to neurite outgrowth. Neurosci Lett. 1996;202:161–164. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers GJ, Avci B, van Hulten P, van Ooyen A, van Pelt J, Pool CW, Lequin MB. The role of calcium signaling in early axonal and dendritic morphogenesis of rat cerebral cortex neurons under non-stimulated growth conditions. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;126:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(00)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehder V, Kater SB. Regulation of neuronal growth cone filopodia by intracellular calcium. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3175–3186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03175.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei K, Shin RM, Inoue T, Kato K, Mikoshiba K. Regulation of nerve growth mediated by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in growth cones. Science. 1998;282:1705–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakar A, Sylar E, Flynn FW. Activation of tachykinin, neurokinin 3 receptors affects chromatin structure and gene expression by means of histone acetylation. Peptides. 2012;38:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallano ML, Buckholz TM, DeLorenzo RJ. Phosphorylation of neurofilament proteins by endogeneous calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1985;130:957–963. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Svitkina T. Filopodia initiation: focus on the Arp2/3 complex and formins. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:402–408. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.5.16971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Kanamaru C, Ohtani A, Li F, Senzaki K, Shiga T. Subtype specific roles of serotonin receptors in the spine formation of cortical neurons in vitro. Neurosci Res. 2011;71:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.07.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JQ, Wan JJ, Poo MM. Essential role of filopodia in chemotropic turning of nerve growth cone induced by a glutamate gradient. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1140–1149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01140.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong LR, Estes S, Artinian L, Rehder V. Acetylcholine elongates neuronal growth cone filopodia via activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Dev Neurobiol. 2013;73:487–501. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]