Abstract

Androgen receptor (AR) signaling initiates mouse prostate development by stimulating prostate ductal bud formation and specifying bud patterns. Curiously, however, prostatic bud initiation lags behind the onset of gonadal testosterone synthesis by about three days. This study’s objective was to test the hypothesis that DNA methylation controls the timing and scope of prostate ductal development by regulating Ar expression in the urogenital sinus (UGS) from which the prostate derives. We determined that Ar DNA methylation decreases in UGS mesenchyme during prostate bud formation in vivo and that this change correlates with decreased DNA methyltransferase expression in the same cell population during the same time period. To examine the role of DNA methylation in prostate development, fetal UGSs were grown in serum-free medium and 5 alpha dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and the DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5AzadC) were introduced into the medium at specific times. As a measure of prostate development, in situ hybridization was used to visualize and count Nkx3-1 mRNA positive prostatic buds. We determined that inhibiting DNA methylation when prostatic buds are being specified, accelerates the onset of prostatic bud development, increases bud number, and sensitizes the budding response to androgens. Inhibition of DNA methylation also reduces Ar DNA methylation in UGS explants and increases Ar mRNA and protein in UGS mesenchyme and epithelium. Together, these results support a novel mechanism whereby Ar DNA methylation regulates UGS androgen sensitivity to control the rate and number of prostatic buds formed, thereby establishing a developmental checkpoint.

Keywords: Epigenetics, steroid hormones, lower urinary tract, UGS

Introduction

Precisely timed hormonal cues mediate several crucial developmental transitions such as metamorphosis in invertebrates and amphibians (1, 2), molting in insects (3, 4), and growth and puberty in mammals (2, 5, 6). During mouse prostate ductal development, precisely timed androgenic cues guide a series of morphogenetic events that include prostatic bud specification (15–16 days post coitus, dpc), initiation (16–18 dpc), elongation (18+ dpc), and branching morphogenesis (birth-postnatal day 15) (7, 8). Our research has been focused on elucidating mechanisms of prostatic bud formation.

Androgens initiate prostatic bud formation by binding and activating androgen receptors (ARs) in urogenital sinus (UGS) mesenchyme during prostatic bud specification (9, 10). ARs are especially abundant in a subpopulation of mouse UGS mesenchymal cells known as lamina propria mesenchyme. Radiolabeled testosterone binding in this cell population is detectable beginning around 15 dpc (11) and coincides with onset of androgen responsive steroid 5 alpha reductase type 2 (Srd5a2) and Wnt inhibitor factor 1 (Wif1) mRNA expression (12, 13). However, mouse prostate development lags behind the onset of gonadal testosterone synthesis and AR binding by several days, a feature shared by other mammalian species (14). Mouse testicular androgen synthesis begins at 13 dpc but prostate bud outgrowth does not begin until three days later, at 16 dpc (15). The lag is not due to the time it takes nascent testicular androgens to reach the UGS, or to accumulate in the UGS at sufficient concentrations, because it cannot be accelerated in vitro by growing UGSs in medium containing physiological or supra-physiological androgen concentrations (16). Additionally, the lag between androgen synthesis and prostatic bud formation is not likely due to the absence of cell types capable of responding to androgenic signals and forming prostatic buds. NK-3 transcription factor locus 1 (Nkx3-1), considered the earliest marker of prostate identity, is detectable in mouse UGS epithelium as early as 15 dpc, about one day before the first prostatic buds are present (17). Further, lineage tracing experiments at 14 dpc reveal a subpopulation of sonic hedgehog (Shh) expressing UGS epithelial cells that contribute to developing prostate bud epithelium (18).

We hypothesized that DNA methylation may function as a molecular switch controlling the transition from prostatic bud specification to initiation. DNA methyltransferases (Dnmts) catalyze addition of a methyl group to the 5’ position of deoxycytidine, which can influence chromatin conformation and gene expression (19). The Dnmt mRNA expression pattern is reorganized between prostatic bud specification and initiation. While Dnmts predominate in UGS mesenchyme during prostatic bud specification, they are more noticeable in UGS epithelium during bud initiation and early branching morphogenesis (20). This temporal change in Dnmt expression coincides with an increase in UGS mesenchymal Ar mRNA expression (21). These previous observations led us to hypothesize that DNMT actions may converge on the Ar to regulate its expression, thereby modulating UGS androgen responsiveness and the onset of prostatic bud formation.

In this study, we found that DNA methylation regulates UGS androgen sensitivity and the timing of prostatic bud formation. The abundance of Ar promoter DNA methylation in UGS mesenchyme decreases during prostatic outgrowth in vivo, coinciding with decreased Dnmt expression over the same period. Administration of a DNA methylation inhibitor during prostatic bud formation in vitro accelerates prostatic bud formation and increases bud number. The DNA methylation inhibitor also acts on the UGS in vitro by reducing Ar DNA methylation, increasing Ar mRNA and protein abundance, and increasing sensitivity of prostatic bud formation to androgens. These results led us to conclude that a regulatory region of the Ar gene is likely methylated prior to prostate bud formation to dampen AR expression and protect against precocious development; DNA methylation is then decreased allowing for androgen-dependent onset of prostatic bud formation. Our findings are important because they provide new testable mechanisms for how prostate development is temporally regulated and how environmental and estrogenic chemicals may perturb prostate development.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild type C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in polysulfone cages containing corn cob bedding and were maintained on a 12 hour light and dark cycle at 25±5ºC and 20–50% relative humidity. Feed (Diet 2019 for males and Diet 7002 for pregnant females, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and water were available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. To obtain timed-pregnant dams, females were paired overnight with males. The next morning was considered 0 days post coitus (dpc). Pregnant dams were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and UGS tissue collected from resulting fetuses. For tissue separations 14 and 17 dpc UGS mesenchyme was enzymatically and mechanically separated from UGS epithelium and homogenized as described previously (22).

In situ hybridization (ISH)

ISH was conducted on whole mount tissues as described previously (12, 23). Detailed protocols for PCR-based riboprobe synthesis are available at www.gudmap.org. Staining patterns were assessed in at least three litter independent tissues per group. Tissues were processed as a single experimental unit to allow for qualitative comparisons among biological replicates and treatment groups.

Organ Culture

Male or female 14 dpc mouse urogenital sinus (UGS) explants were placed on 0.4-µm Millicell-CM filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and cultured as described previously (7). Medium was supplemented with one or all of the following: 0.01–10 nM final concentration 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) dissolved in ethanol (0.1%), 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle control) or DMSO containing 5 µM 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5AzadC, A3635, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Medium and supplements were changed every 2 days.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunofluorescent staining of ISH-stained tissues and paraffin sections was performed as described previously (12, 23). Primary antibodies were diluted as follows: 1:200 rabbit anti-CDH1 (3195, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), 1:250 mouse anti-CDH1 (610181, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA) 1:50 mouse anti-KRT14 (ms-115-p0, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1:250 rabbit anti-AR (sc-816, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), 1:200 rabbit anti-DNMT1 (5032, Cell Signaling Technology). Secondary antibodies were diluted as follows: 1:250 Dylight 549-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (111-507-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), 1:250 Dylight 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (111-487-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and 1:250 Dylight 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (115-487-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Immunofluorescently labeled tissues were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dilactate (DAPI), and mounted in antifade medium (phosphate buffered saline containing 80% glycerol and 0.2% n-propyl gallate). Whole mount immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (23). Primary antibody was diluted 1:750 rabbit anti-CDH1 and secondary antibody was diluted 1:500 biotin conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (BA-1000, Vector, Burlingame, CA).

Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP)

MeDIP was conducted as described previously (24). UGS explants were pooled (5–6 tissues/pool) and each experimental group consisted of five pools. Real time quantitative PCR (QPCR) was performed as described previously (13) using gene specific primers for mouse Ar: 5’-AGAGACGAGGAGGCAGGATAAG-3’ and 5’-CGCTCCTCGATAGGTCTTGG-3’ (Entrez gene ID 11835) spanning the region +58bp to −84bp of the transcription start site (TSS).

Pyrosequencing of Bisulfite Converted DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated using the Qiagen DNeasey Blood and Tissue Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Bisulfite conversion of DNA was performed using the Qiagen Epitect Bisulfite Kit per manufacturer’s instructions. Calibration standards of highly methylated DNA, prepared as described previously (25), and unmethylated DNA, prepared using the Qiagen REPLI-g Mini Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions, were used as controls. One microgram of bisulfite treated DNA was used to generate PCR amplified templates for pyrosequencing. Fifty microliter PCR reactions consisted of bisulfite DNA, 1× GoTaq Buffer, 0.4mM dNTP, 0.3uM primers and 0.05U/uL GoTaq (Promega, Madison, WI) and the following primers generated by PyroMark 2.0 software: Ar (NC_000086.7) (+209 to + 230 of Ar TSS) forward 5’-GTTTAAGGATGGAGGTGTAGTTAG-3’, and biotinylated reverse 5’-AAACCAAATAACCTATAAAACCTCTAAT-3’. PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C × 5min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C × 30s, 50°C × 30s, and 72°C × 1min followed by 72°C for 5 min. Ten microliters of biotinylated PCR product was used for each sequencing assay, which included the following sequencing primer: 5’-ATAGTAGAGGTAGGAGATTAGTTT-3’. Pyrosequencing was performed using PyroMark Gold Q96 reagents (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden) and streptavidin sepharose beads (GE, Cat# 17-5113-01) with the PSQ HS 96 Pyrosequencer. Percent methylation of each CpG was determined using Pyro Q-CpG Software (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden). Average methylation at each CpG was calculated from three technical replicates with at least three litter independent sample pools per group.

Real Time Quantitative PCR (QPCR)

QPCR was conducted as described previously (13) on UGS explant pools (5–6 tissues/pool) with five pools per experimental treatment group using the following gene specific primers: Ar, 5’-GATGGTATTTGCCATGGGTTG-3’ and 5’-GGCTGTACATCCGAGACTTGTG-3’ and peptidyl prolyl isomerase a (Ppia), 5′-TCTCTCCGTAGATGGACCTG-3′ and 5′-ATCACGGCCGATGACGAGCC-3′. Relative mRNA abundance was determined by the ΔΔCt method as described previously (26) and normalized to Ppia abundance.

Statistical analyses

For prostatic bud counting, UGSs were stained by ISH for Nkx3-1 mRNA and counted as described previously (23). For immunolabeled cell counting, AR positive cells were counted in at least two sections from three litter independent tissues per treatment group. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 2.13.1. Homogeneity of variance was determined using Bartlett’s test. Student’s T-test, one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests were used to identify significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between or among treatment groups.

Results

DNA Methylation Regulates Prostatic Ductal Development by Restricting Bud Formation

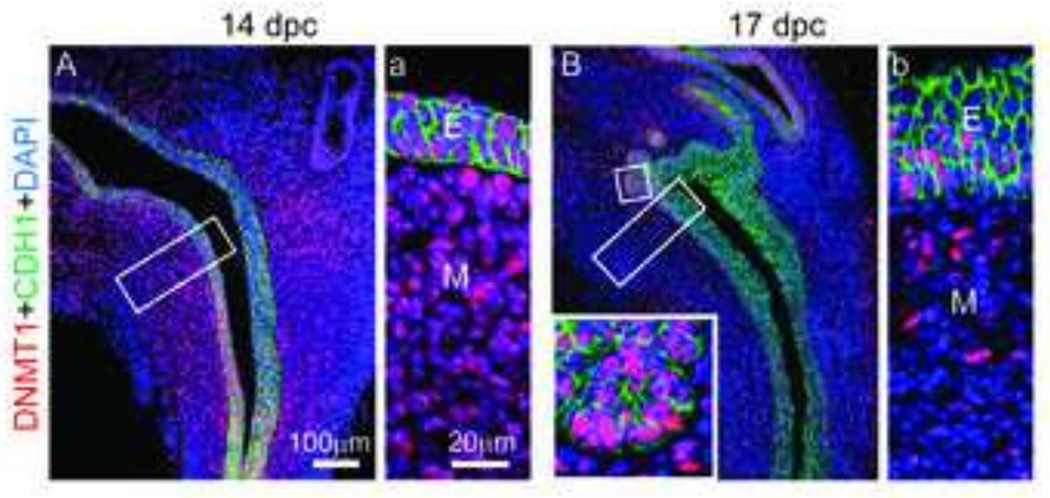

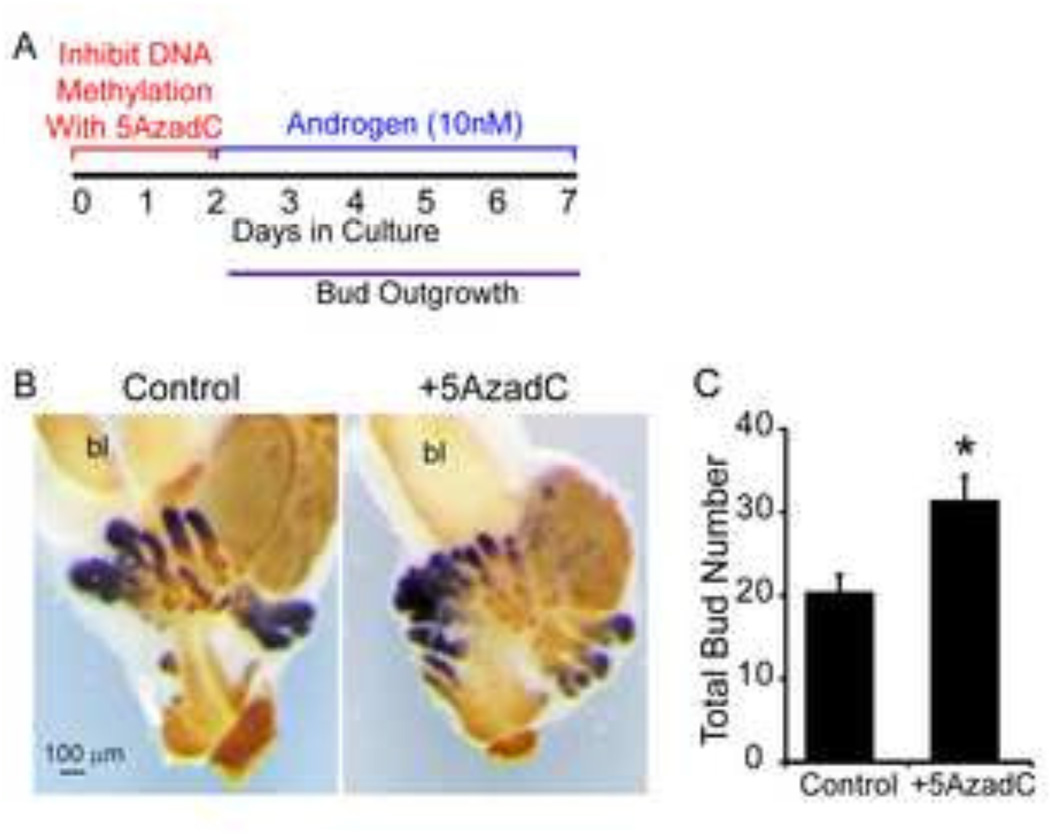

We previously reported that the spatial pattern of DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1) mRNA changes during early prostate development (20). Here, we demonstrate that DNMT1 protein follows the same spatiotemporal expression pattern as its mRNA. During prostatic bud specification, DNMT1 protein predominates in UGS mesenchyme (Fig. 1A). During prostatic bud initiation and outgrowth, DNMT1 protein is diminished in UGS mesenchyme and is abundant in UGS epithelium and prostatic buds (Fig. 1B). This change in DNMT1 protein expression pattern over the course of prostatic bud formation led us to hypothesize DNA methylation elicits different actions at each stage of prostatic bud formation. To elucidate the early stage actions of DNA methylation, we pulse-treated UGSs with a DNA methylation inhibitor during specification (when DNMT1 predominates in mesenchyme) and examined subsequent bud formation. UGSs were collected from 14 dpc male mouse fetuses (prior to prostatic formation), grown for two days in androgen-free medium containing DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) alone, then grown for an additional five days in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT) but no DNA methylation inhibitor (Fig. 2A). UGS explants were stained by ISH to visualize the prostate marker, NK-3 transcription factor, locus 1 (Nkx3-1) (23, 27, 28) and by IHC to visualize UGS epithelium so that prostatic buds could be counted. UGS explants cultured in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor during the first two days of a seven day culture period formed a greater number of buds compared to controls (Fig. 2B–C).

Figure 1. DNMT1 protein abundance diminishes in the mesenchyme during prostate development.

(A,a) 14 dpc and (B,b) 17 dpc lower urinary tract sagittal sections were stained by immunohistochemistry to visualize DNMT1 (red) protein and all epithelium E-cadherin (CDH1, green). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Insets represent magnified images. Abbreviations: E, epithelium; M, mesenchyme.

Figure 2. DNA methylation restricts prostate bud number.

(A) 14 dpc male UGSs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) alone followed by 5 days in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT) alone. (B) Following culture tissues were stained by ISH to visualize prostate bud marker NK-3 transcription factor locus 1 (Nkx3-1) (purple) and IHC to visualize all epithelium (E-cadherin, CDH1, brown). (C) Quantification of total prostatic bud number in control and 5AzadC treated samples. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05. Abbreviations: bl, bladder.

We next tested whether inhibition of DNA methylation augments prostatic bud formation specifically in male UGS, or whether this action is generalizable to both male and female UGS. Although male and female UGS development differs in vivo, female UGSs can be induced by exogenous androgens to form prostatic buds in a pattern that approximates bud formation in males (29). Female UGS explants grown in the presence of 5AzadC during the first two days of a seven day culture period also formed a greater number of buds compared to controls (Supplemental Figure 1A–B) and formed a similar number of buds compared to male UGSs grown in the presence of 5AzadC during the first two days of a seven day culture period (Supplemental Figure 1C). Both male and female UGSs grown in the presence of 5AzadC during the first two days of a seven day culture have similar histology (Supplemental Figure 1D) and appear to have shorter buds compared to control UGSs, a phenotype consistent with that previously reported (24). Together these results are consistent with DNA methylation functioning as a general mechanism to refine androgen dependent prostatic development by restricting the number of prostatic buds formed.

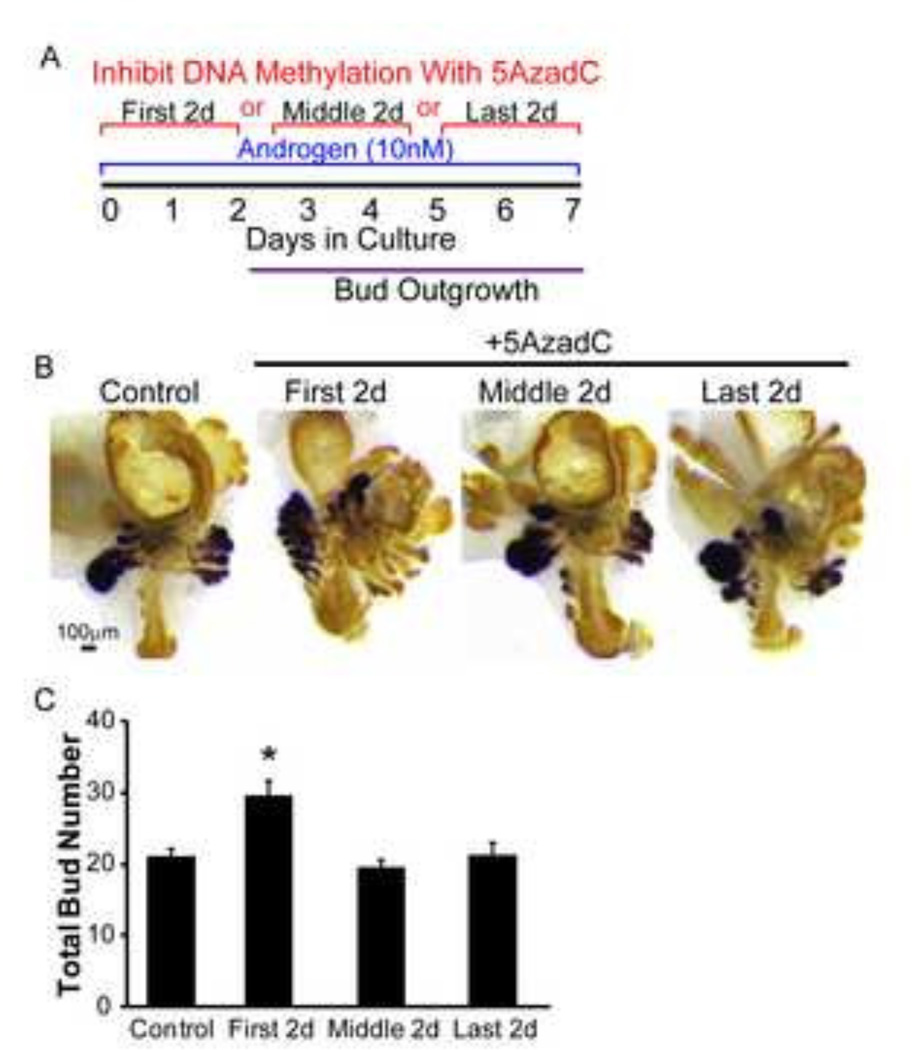

DNA Methylation Acts During Early Development to Control Prostatic Bud Formation

The DNMT1 protein expression pattern changes from UGS mesenchyme dominant to UGS epithelium dominant during the period spanning mouse prostatic bud specification, initiation and outgrowth (Fig. 1). To test whether inhibition of DNA methylation augments prostatic bud formation during all stages of prostatic bud formation, or exclusively during the specification stage when DNMT1 predominates in UGS mesenchyme, male 14 dpc UGS explants were pulse-treated with 5AzadC during the first two days (prior to bud outgrowth, during specification), middle two days (during bud initiation) or last two days (during bud elongation) of a seven day culture period in medium containing androgen (10nM DHT) (Fig. 3A). UGS explants were then stained and prostatic buds counted as described above (Fig. 3B). 5AzadC significantly increased bud number if administered during the first two days of culture but not during the middle or last two days (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that DNA methylation functions during prostatic bud specification, but not during bud initiation and elongation, to control the number of prostatic buds formed.

Figure 3. DNA methylation acts during specification to restrict prostate bud number.

(A) 14 dpc male UGSs were cultured in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT) and DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) either on the first, middle or last 2 days of culture. (B) Tissues were stained by ISH for NK-3 transcription factor locus 1 (Nkx3-1) (purple) to visualize prostate buds and IHC to visualize all epithelium (E-cadherin, CDH1, brown). (C) Quantification of total prostatic bud number in control and 5AzadC treated samples. Results are mean ± SE, n≥3/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05.

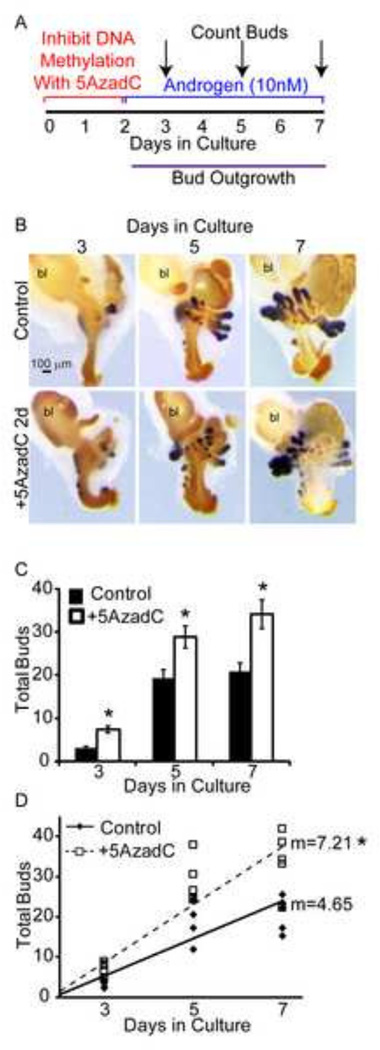

DNA Methylation Controls the Rate of Androgen Dependent Prostatic Bud Formation

We hypothesized inhibition of DNA methylation may augment prostatic bud number by allowing an increased number of prostatic buds to form during the earliest stages of prostatic ductal development. To test this hypothesis, we exposed 14 dpc male UGSs to a single two day pulse of 5AzadC or vehicle alone, and then examined prostatic bud formation after one, three, or five additional days of growth in medium containing androgens but no 5AzadC. UGS explants were stained and total prostatic bud number quantified as described above (Fig. 4B). UGSs that were pulse treated with 5AzadC showed significantly more prostatic buds at all three time points than control-treated UGSs (Fig. 4C). Linear regression analysis revealed that 5AzadC-treated UGSs had a significantly greater rate of prostatic bud formation than control-treated UGSs (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that DNA methylation acts to control the timing and rate of androgen-induced prostatic bud formation from the initial stages of prostate development.

Figure 4. DNA methylation restricts rate of prostate bud formation.

(A) 14 dpc male UGSs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) alone followed by 1, 3 or 5 additional days in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT) alone. (B) Tissues were stained by ISH for prostate bud marker NK-3 transcription factor locus 1 (Nkx3-1) (purple) and IHC to visualize all epithelium (E-cadherin, CDH1, brown). (C) Quantification of total buds formed at each timepoint. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05. (D) Linear regression of the rate of bud formation, analysis of covariance revealed a significant difference between treatment groups (p=0.004). Abbreviations: bl, bladder.

DNA Methylation Controls Androgen Sensitivity During Androgen Dependent Prostate Development

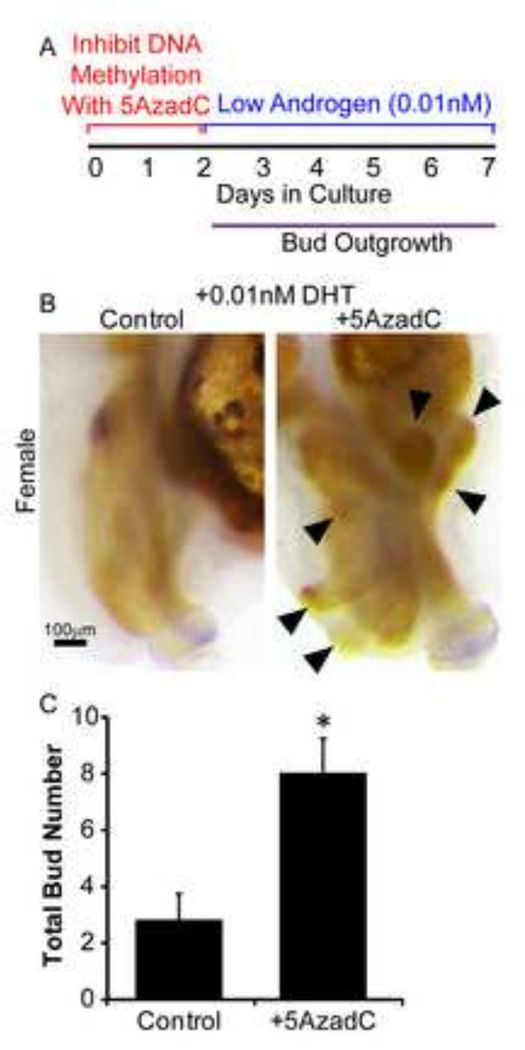

The number of prostatic buds formed in control C57BL/6J fetuses is highly reproducible between individual mice (8) and in explant cultures (23). Our results support the hypothesis that DNA methylation is one factor that restricts the quantity of prostatic buds formed. One possible mechanism by which this restriction occurs is that DNA methylation regulates UGS sensitivity to androgens. To examine this mechanism, we tested whether inhibition of DNA methylation augments prostatic bud formation in a low androgen environment. Male UGSs already exhibit androgen-induced gene expression at 14dpc (12). To ensure that UGSs used in this experiment were naïve to high androgen levels prior to the culture period, we used female UGSs, which also form prostatic buds in response to androgens (24, 29). Female UGSs were grown for two days in medium containing 5AzadC (5µM) or vehicle alone, followed by five additional days in medium containing androgen alone. The androgen concentration in this study (0.01nM DHT) was 1000× lower than the concentration traditionally used to support prostate morphogenesis in mouse UGS organ culture (9, 7) and is lower than the DHT concentration sufficient to mimic the same budding response of UGSs cultured with 15–17dpc testes or physiologically relevant concentrations of testosterone (16). While female UGSs are capable of forming small androgen independent buds (7), the addition of 5AzadC caused female UGSs to form significantly more buds (by at least two fold) versus control UGSs (Fig. 5). These results indicate that DNA methylation regulates prostatic bud formation at least in part by regulating androgen sensitivity of the budding response.

Figure 5. DNA methylation controls developing prostate androgen sensitivity.

(A) 14 dpc female UGSs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) alone followed by 5 days in medium containing androgen (0.01nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT) alone. (B) Tissues were stained by ISH for prostate bud marker NK-3 transcription factor locus 1 (Nkx3-1) (purple) and IHC to visualize all epithelium (E-cadherin, CDH1, brown). (C) Quantification of total bud number in control and 5AzadC tissues. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05. Arrowheads indicate epithelial buds.

DNA Methylation of the Androgen Receptor Controls Prostate Bud Formation

We have shown that inhibition of DNA methylation via 5AzadC enhances prostatic bud number and increases androgen sensitivity. One potential mechanism to explain both of these results is that 5AzadC reduces Ar DNA methylation, thereby increasing Ar mRNA and protein expression. The Ar gene locus contains a 1.5kb CpG island that encompasses the transcription start site and exon 1, a region that is actively methylated in humans and rodents (30–32). DNA methylation changes within this region have been demonstrated in cell lines (33) and C57Bl/6 mouse tissues (32). We used this known region of Ar DNA methylation to examine whether 5AzadC is capable of decreasing Ar DNA methylation in mouse UGS explants, and to validate analytical tools for assessing Ar DNA methylation. 14 dpc female UGS explants were cultured in the presence of androgen alone or androgen and 5AzadC, then pyrosequencing of bisulfite converted DNA was performed on isolated UGS tissues. DNA methylation was detected at all sites (Supplemental Figure 2) and 5AzadC significantly reduced the percentage of DNA methylation at five of five CpG sites in the region analyzed (Supplemental Figure 2).

While pyrosequencing demonstrated decreased DNA methylation of the Ar CpG region following 5AzadC treatment, this method cannot discriminate between 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, a base modification that can mediate DNA demethylation (34) and that could potentially confound our results. Therefore, we used methylated DNA immunoprecipitation followed by QPCR (MeDIP-QPCR), a method specific to 5-methylcytosine-mediated DNA methylation, to independently confirm our pyrosequencing results. Using QPCR primers designed to amplify the same region examined by pyrosequencing, the MeDIP-QPCR results corroborated our pyrosequencing results, showing that 5AzadC significantly reduces Ar DNA methylation in mouse UGS (Supplemental Figure 2) and validating use of MeDIP-QPCR for analysis of Ar DNA methylation in this study.

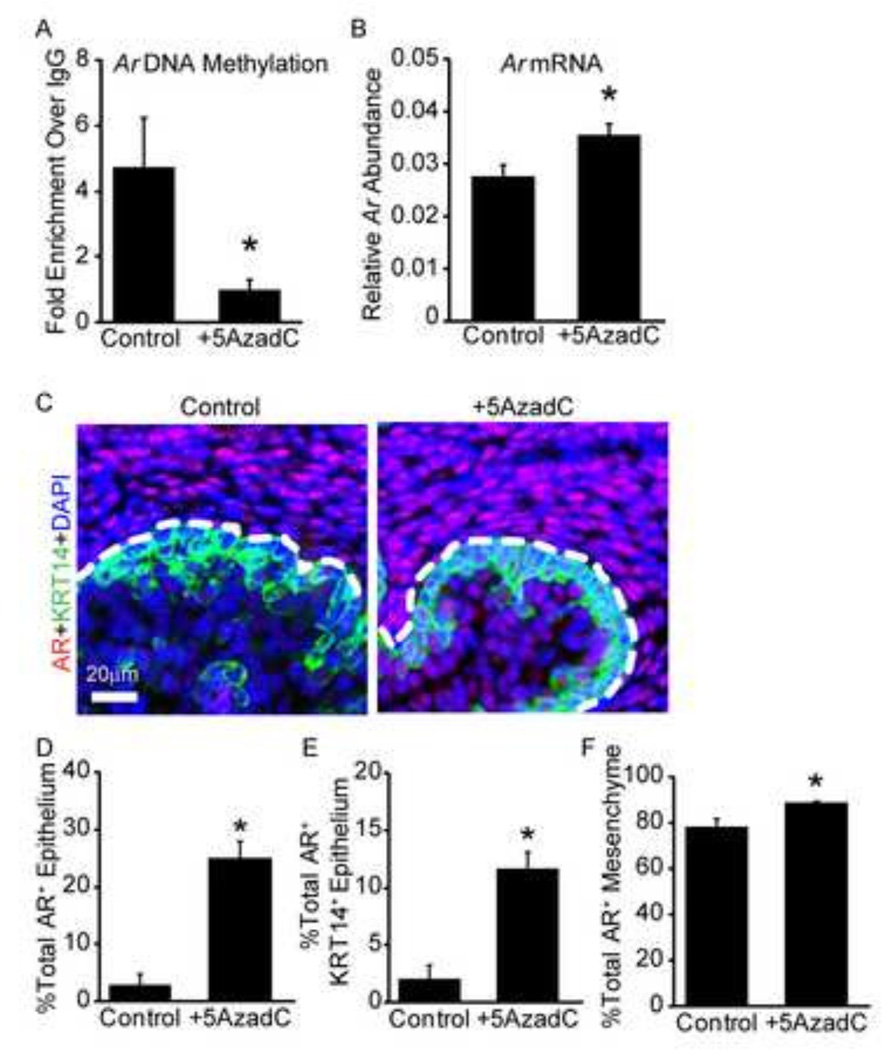

We next used MeDIP-QPCR, along with RT-QPCR and immunostaining, to test whether 5AzadC treatment influences Ar DNA methylation status and mRNA and protein expression during prostatic bud specification. 14 dpc male UGS explants were cultured for two days in the presence of androgens and either 5AzadC or vehicle, after which Ar promoter DNA methylation was measured by MeDIP-QPCR. 5AzadC significantly decreased Ar promoter DNA methylation (Fig. 6A) and also increased Ar mRNA (Fig. 6B) and protein abundance (Fig. 6C–F). 5AzadC treatment increased the frequency of detectable AR staining in UGS epithelial cells by almost 20%, detectable AR staining in KRT14+ basal epithelial cells by nearly 10%, and detectable AR staining in UGS mesenchyme cells by 10% (Fig. 6D–F). These results reveal that 5AzadC decreases Ar promoter DNA methylation and increases AR expression, suggesting a possible mechanism for the increased androgen sensitivity of the prostatic budding response we observed.

Figure 6. Androgen Receptor (Ar) DNA methylation is correlated with mRNA and protein abundance.

14 dpc male UGSs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT). (A) Ar DNA methylation assessed by methylated DNA immunoprecipitation and normalized to IgG control. (B) Relative Ar mRNA abundance quantified by real time QPCR relative to peptidyl prolyl isomerase a (Ppia). (C) AR protein (red) and basal epithelium (keratin 14, KRT14, green) were visualized using immunohistochemistry. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Dotted line indicates the boundary between mesenchyme and epithelium. Quantification of percent total AR positive cells in (D) all epithelium (E) KRT14+ basal epithelium and (F) mesenchyme. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05.

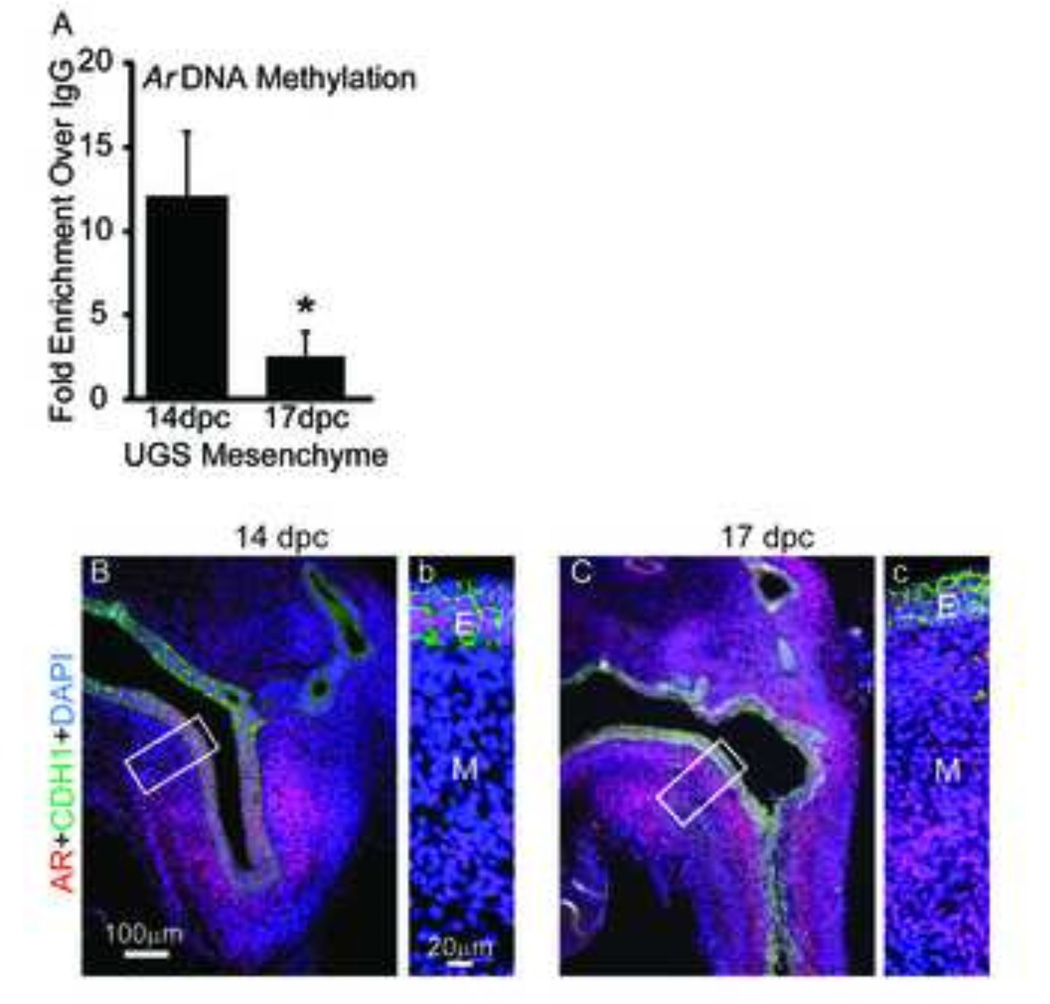

Based on the above in vitro findings and the diminished expression of Dnmts in mesenchyme from 14 dpc to 17 dpc (Fig. 1) (20), we tested the hypothesis that Ar DNA methylation also decreases in UGS mesenchyme over the course of prostate bud formation. 14 and 17 dpc male UGS mesenchyme was isolated and Ar promoter DNA methylation measured by MeDIP-QPCR. The Ar promoter was more highly methylated in male UGS mesenchyme at 14 dpc compared to 17 dpc (Fig. 7A). This temporal change in Ar DNA methylation coincides with an increase in UGS mesenchymal Ar mRNA (21) and protein expression from 14 dpc to 17 dpc (Fig. 7B–C). These results provide evidence in vivo for the potential mechanism we identified with inhibiting DNA methylation in vitro: Ar DNA methylation is diminished during initiation of prostate development to trigger an increase in AR expression and androgen-dependent prostatic bud formation.

Figure 7. Androgen receptor (Ar) DNA methylation is correlated with AR protein abundance in vivo.

(A) UGS mesenchyme was isolated from 14 dpc and 17 dpc male UGS. Ar DNA methylation assessed by methylated DNA immunoprecipitation and normalized to IgG control. (B,b) 14 dpc and (C,c) 17 dpc lower urinary tract sagittal sections were stained by immunohistochemistry to visualize AR (red) E-cadherin protein (CDH1, green). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Insets represent magnified images. Abbreviations: E, epithelium; M, mesenchyme. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05.

Discussion

Our results suggest a link between DNA methylation and androgen responsive prostatic bud growth through a mechanism likely involving the AR. Inhibiting DNA methylation in the UGS prior to prostatic bud formation decreases Ar promoter DNA methylation, increases Ar mRNA and protein abundance, increases UGS sensitivity to androgens, and causes the UGS to form prostatic buds at an earlier stage and in greater number. These results suggest that DNA methylation establishes a developmental checkpoint that restricts UGS androgen sensitivity and responsiveness prior to the onset of prostate development.

The tools for investigating mechanistic roles of DNA methylation at specific CpG loci are limited. We used a pharmacological approach to identify prostate developmental phenotypes associated with carefully timed exposure to a global DNA methylation inhibitor, 5AzadC. While 5AzadC is capable of inhibiting DNA methylation across the genome, other studies using this drug reveal its scope of action on gene expression is surprisingly narrow - often involving only a few hundred genes (35). We previously used 5AzadC as a chemical probe to demonstrate a crucial role for E-cadherin DNA methylation in prostatic bud outgrowth (24). Here, using the same approach but modifying the timing of 5AzadC exposure, we revealed a second prostate development phenotype linked to DNA methylation – the timing and scope of prostatic bud formation. While we acknowledge that many potential DNA methylation sites could contribute to this process, our collective results point toward DNA methylation of the Ar promoter as playing a key role in this process. Specifically, we showed that 5AzadC 1) increases the number of prostatic buds formed in culture, 2) accelerates the rate of prostatic bud formation, 3) causes a greater quantity of prostate buds to form under low androgen concentrations, 4) significantly decreases Ar promoter DNA methylation, 5) significantly increases Ar mRNA abundance and 6) significantly increases the percentage of AR protein-positive cells in the UGS. We also confirmed in vivo that Ar promoter DNA methylation decreases from 14 to 17 dpc.

Our results indicate that the DNA methylation status of the male mouse UGS prior to prostatic bud formation influences the pattern and number of prostatic buds it will form. Several environmental chemicals and estrogenic chemicals inappropriately influence prostate budding and our new results may shed light on the mechanisms by which these chemicals act on the UGS to influence prostate development. For example, bisphenol A (BPA), diethylstilbestrol and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin modulate the number and pattern of prostatic buds formed in fetal mice (7, 36) and have separately been shown to influence DNA methylation patterns in mouse UGS and elsewhere (37, 38). BPA also increases AR expression in the UGS, but the responsible mechanisms have not been identified (39). Our new results suggest the intriguing hypothesis that BPA, and potentially other estrogenic chemicals, may influence prostatic bud formation by altering Ar DNA methylation in the UGS.

Fetal mouse prostatic bud formation trails the onset of testicular testosterone synthesis by about three days. The cause for this delay between onset of androgen synthesis and initiation of androgen-dependent prostate bud formation is not known. We showed that prostate androgen sensitivity and bud formation can be enhanced in the presence of a DNA methylation inhibitor, thereby revealing the possibility that DNA methylation of the Ar promoter may account for this delay, safeguarding against precocious development of prostatic buds. How DNA methylation is regulated in the UGS and whether DNA methylation continues to control prostate androgen sensitivity throughout life is unknown. Further, whether DNA methylation guides checkpoints of hormonal responsiveness in other developing hormone responsive tissues is yet to be determined.

An interesting finding resulting from our studies is that the DNA methylation inhibitor enhanced AR expression not only in UGS mesenchyme, where it is known to be necessary for prostate development (40), but also in UGS epithelium. There was a 20% increase in AR positive cells in the epithelium of UGSs treated with 5AzadC versus control and a 10% increase in mesenchyme. AR is not required in UGS epithelium for prostate development (40), but the consequence of precocious epithelial AR expression during prostatic bud formation has never been examined. Determining the consequence of increased UGS epithelial AR and whether changes in Ar DNA methylation in UGS mesenchyme or epithelium are responsible for enhanced budding in response to 5AzadC pose intriguing avenues of future study.

How DNA methylation of the Ar is reduced during the course of prostate bud formation is unknown. Possible mechanisms include: 1) Passive DNA demethylation whereby DNA methylation is not maintained upon subsequent cell divisions potentially by downregulating DNMT1. 2) Active DNA demethylation which occurs when methylated cytosines undergo base modifications that in turn trigger DNA mismatch repair or base excision repair pathways, leading to replacement with unmethylated cytosines. Several of the enzymes capable of modifying methylated cytosines to trigger base excision are present in the developing prostate (20). Whether one or both of these mechanisms contributes to the decrease in Ar DNA methylation during prostate development remains to be determined.

Supplementary Material

14 dpc female UGSs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) alone followed by 5 days in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT) alone. (A) Following culture tissues were stained by ISH to visualize prostate bud marker NK-3 transcription factor locus 1 (Nkx3-1) (purple) and IHC to visualize all epithelium (E-cadherin, CDH1, brown). (B) Quantification of total prostatic bud number in control and 5AzadC treated samples. (C) Quantification of total prostatic bud number in male and female 5AzadC treated UGSs. (D) Representative hematoxolin and eosin staining in male and female UGSs cultured in the presence of 5AzadC for 2 days followed by 5 days in medium containing DHT. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05. Solid line outlines epithelium. Abbreviations: bl, bladder.

14 dpc UGSs were cultured for 4 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT). (A–B) Pyrosequencing of bisulfite converted DNA with primers designed to target a CpG dense region of the Ar (+209 to +230 of the TSS). Results reported as percent Ar DNA methylation. (C) Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation followed by QPCR (MeDIP-QPCR) was used to confirm pyrosequencing results. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05.

Highlights.

Inhibiting DNA methylation increases prostate bud number and rate of formation.

Inhibiting DNA methylation sensitizes the budding response to androgens.

DNA methylation regulates androgen receptor (Ar) expression in developing prostate.

Ar DNA methylation is a checkpoint controlling onset and scope of prostate budding.

Acknowledgements

Grant Sponsors: National Institutes of Health Grants DK099328, DK083425, DK070219, DK096074 and ES001332, and National Science Foundation Grant DGE-0718123. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kulkarni SS, Buchholz DR. Corticosteroid signaling in frog metamorphosis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2014;203:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Cara F, King-Jones K. How clocks and hormones act in concert to control the timing of insect development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2013;105:1–36. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396968-2.00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ono H. Ecdysone differentially regulates metamorphic timing relative to 20-hydroxyecdysone by antagonizing juvenile hormone in drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. 2014;391:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki Y, Koyama T, Hiruma K, Riddiford LM, Truman JW. A molt timer is involved in the metamorphic molt in manduca sexta larvae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:12518–12525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311405110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurian JR, Keen KL, Guerriero KA, Terasawa E. Tonic control of kisspeptin release in prepubertal monkeys: implications to the mechanism of puberty onset. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3331–3336. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker DM, Kermath BA, Woller MJ, Gore AC. Disruption of reproductive aging in female and male rats by gestational exposure to estrogenic endocrine disruptors. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2129–2143. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vezina CM, Allgeier SH, Moore RW, Lin T, Bemis JC, Hardin HA, Gasiewicz TA, Peterson RE. Dioxin causes ventral prostate agenesis by disrupting dorsoventral patterning in developing mouse prostate. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;106:488–496. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugimura Y, Cunha GR, Donjacour AA. Morphogenesis of ductal networks in the mouse prostate. Biol. Reprod. 1986;34:961–971. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod34.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allgeier SH, Lin T, Moore RW, Vezina CM, Abler LL, Peterson RE. Androgenic regulation of ventral epithelial bud number and pattern in mouse urogenital sinus. Dev. Dyn. 2010;239:373–385. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasnitzki I, Mizuno T. Prostatic induction: interaction of epithelium and mesenchyme from normal wild-type mice and androgen-insensitive mice with testicular feminization. J. Endocrinol. 1980;85:423–428. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0850423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda H, Lasnitzki I, Mizuno T. Change of mosaic patterns by androgens during prostatic bud formation in Xtfm/X+ heterozygous female mice. J. Endocrinol. 1987;114:131–137. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1140131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abler LL, Keil KP, Mehta V, Joshi PS, Schmitz CT, Vezina CM. A high-resolution molecular atlas of the fetal mouse lower urogenital tract. Dev. Dyn. 2011;240:2364–2377. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keil KP, Mehta V, Branam AM, Abler LL, Buresh-Stiemke RA, Joshi PS, Schmitz CT, Marker PC, Vezina CM. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (wif1) is regulated by androgens and enhances androgen-dependent prostate development. Endocrinology. 2012;153:6091–6103. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson JD, Leihy MW, Shaw G, Renfree MB. Unsolved problems in male physiology: studies in a marsupial. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003;211:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin T, Rasmussen NT, Moore RW, Albrecht RM, Peterson RE. Region-specific inhibition of prostatic epithelial bud formation in the urogenital sinus of c57bl/6 mice exposed in utero to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol. Sci. 2003;76:171–181. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lasnitzki I, Mizuno T. Induction of the rat prostate gland by androgens in organ culture. J. Endocrinol. 1977;74:47–55. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0740047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia-Gaur R, Donjacour AA, Sciavolino PJ, Kim M, Desai N, Young P, Norton CR, Gridley T, Cardiff RD, Cunha GR, Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. Roles for Nkx3-1 in prostate development and cancer. Genes and Development. 1999;13:966–977. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta V, Schmitz CT, Keil KP, Joshi PS, Abler LL, Lin TM, Taketo MM, Sun X, Vezina CM. Beta-catenin (CTNNB1) induces Bmp expression in urogenital sinus epithelium and participates in prostatic bud initiation and patterning. Dev. Biol. 2013;376:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 2003;33(Suppl):245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keil KP, Altmann HM, Mehta V, Abler LL, Elton EA, Vezina CM. Catalog of mrna expression patterns for dna methylating and demethylating genes in developing mouse lower urinary tract. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2013;13:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeda H, Chang C. Immunohistochemical and in-situ hybridization analysis of androgen receptor expression during the development of the mouse prostate gland. J. Endocrinol. 1991;129:83–89. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1290083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vezina CM, Allgeier SH, Fritz WA, Moore RW, Strerath M, Bushman W, Peterson RE. Retinoic acid induces prostatic bud formation. Dev. Dyn. 2008;237:1321–1333. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keil KP, Mehta V, Abler LL, Joshi PS, Schmitz CT, Vezina CM. Visualization and quantification of mouse prostate development by in situ hybridization. Differentiation. 2012;84:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keil KP, Abler LL, Mehta V, Altmann HM, Laporta J, Plisch EH, Suresh M, Hernandez LL, Vezina CM. Dna methylation of e-cadherin is a priming mechanism for prostate development. Dev. Biol. 2014;387:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tost J, Gut IG. Dna methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2265–2275. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr and the 2(-delta delta c(t)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bieberich CJ, Fujita K, He WW, Jay G. Prostate-specific and androgen-dependent expression of a novel homeobox gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31779–31782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sciavolino PJ, Abrams EW, Yang L, Austenberg LP, Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Tissue-specific expression of murine nkx3.1 in the male urogenital system. Dev. Dyn. 1997;209:127–138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199705)209:1<127::AID-AJA12>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunha GR. Age-dependent loss of sensitivity of female urogenital sinus to androgenic conditions as a function of the epithelia-stromal interaction in mice. Endocrinology. 1975;97:665–673. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-3-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jarrard DF, Kinoshita H, Shi Y, Sandefur C, Hoff D, Meisner LF, Chang C, Herman JG, Isaacs WB, Nassif N. Methylation of the androgen receptor promoter cpg island is associated with loss of androgen receptor expression in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5310–5314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi S, Inaguma S, Sakakibara M, Cho Y, Suzuki S, Ikeda Y, Cui L, Shirai T. Dna methylation in the androgen receptor gene promoter region in rat prostate cancers. Prostate. 2002;52:82–88. doi: 10.1002/pros.10099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J, Oh M, Yoon C, Bae J, Kim J, Moon D. The effect of diet-induced insulin resistance on dna methylation of the androgen receptor promoter in the penile cavernosal smooth muscle of mice. Asian J. Androl. 2013;15:487–491. doi: 10.1038/aja.2013.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian J, Lee SO, Liang L, Luo J, Huang C, Li L, Niu Y, Chang C. Targeting the unique methylation pattern of androgen receptor (ar) promoter in prostate stem/progenitor cells with 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (5-aza) leads to suppressed prostate tumorigenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:39954–39966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohr F, Dohner K, Buske C, Rawat VP. TET genes: new players in DNA demethylation and important determinants for stemness. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamashita S, Tsujino Y, Moriguchi K, Tatematsu M, Ushijima T. Chemical genomic screening for methylation-silenced genes in gastric cancer cell lines using 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine treatment and oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timms BG, Howdeshell KL, Barton L, Bradley S, Richter CA, vom Saal FS. Estrogenic chemicals in plastic and oral contraceptives disrupt development of the fetal mouse prostate and urethra. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:7014–7019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502544102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang W, Morey LM, Cheung YY, Birch L, Prins GS, Ho S. Neonatal exposure to estradiol/bisphenol a alters promoter methylation and expression of nsbp1 and hpcal1 genes and transcriptional programs of dnmt3a/b and mbd2/4 in the rat prostate gland throughout life. Endocrinology. 2012;153:42–55. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S, Hursting SD, Davis BJ, McLachlan JA, Barrett JC. Environmental exposure, dna methylation, and gene regulation: lessons from diethylstilbesterol-induced cancers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;983:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richter CA, Taylor JA, Ruhlen RL, Welshons WV, Vom Saal FS. Estradiol and bisphenol a stimulate androgen receptor and estrogen receptor gene expression in fetal mouse prostate mesenchyme cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:902–908. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunha GR. The role of androgens in the epithelio-mesenchymal interactions involved in prostatic morphogenesis in embryonic mice. Anat. Rec. 1973;175:87–96. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091750108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

14 dpc female UGSs were cultured for 2 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) alone followed by 5 days in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT) alone. (A) Following culture tissues were stained by ISH to visualize prostate bud marker NK-3 transcription factor locus 1 (Nkx3-1) (purple) and IHC to visualize all epithelium (E-cadherin, CDH1, brown). (B) Quantification of total prostatic bud number in control and 5AzadC treated samples. (C) Quantification of total prostatic bud number in male and female 5AzadC treated UGSs. (D) Representative hematoxolin and eosin staining in male and female UGSs cultured in the presence of 5AzadC for 2 days followed by 5 days in medium containing DHT. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05. Solid line outlines epithelium. Abbreviations: bl, bladder.

14 dpc UGSs were cultured for 4 days in the presence of DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5µM, 5AzadC) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) in medium containing androgen (10nM dihydrotestosterone, DHT). (A–B) Pyrosequencing of bisulfite converted DNA with primers designed to target a CpG dense region of the Ar (+209 to +230 of the TSS). Results reported as percent Ar DNA methylation. (C) Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation followed by QPCR (MeDIP-QPCR) was used to confirm pyrosequencing results. Results are mean ± SE, n=5/group. Asterisk indicates significant difference from control p≤0.05.