Abstract

Although there is a rich literature on the role of dopamine in value learning, much less is known about its role in using established value estimations to shape decision-making. Here we investigated the effect of dopaminergic modulation on value-based decision-making for food items in fasted healthy human participants. The Becker-deGroot-Marschak auction, which assesses subjective value, was examined in conjunction with pharmacological fMRI using a dopaminergic agonist and an antagonist. We found that dopamine enhanced the neural response to value in the inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus, and that this effect predominated toward the end of the valuation process when an action was needed to record the value. Our results suggest that dopamine is involved in acting upon the decision, providing additional insight to the mechanisms underlying impaired decision-making in healthy individuals and clinical populations with reduced dopamine levels.

Keywords: decision, dopamine, food, reward, value

Introduction

Successful interactions with the environment, those that maximize reward and minimize punishment, entail using previous experience to predict the likely value of outcomes and the actions that obtain them. Animal and human studies have strongly implicated the neurotransmitter dopamine in this value learning process (Schultz et al., 1997; Schultz, 1998; Frank et al., 2004; Wise, 2004; Bayer and Glimcher, 2005; Frank and O'Reilly, 2006; Pessiglione et al., 2006; Steinberg et al., 2013), in addition to its other overlapping roles in shaping behavior, including motivation (Berridge and Robinson, 1998), vigor (Niv et al., 2007), and behavioral activation (Robbins and Everitt, 2007).

But choice requires not merely an ability to predict the consequences of one's actions. One must be able to weigh up the likely values of competing possibilities. Thus, it is critical to retrieve and represent the subjective values of the options on offer to select the most valuable one. This value computation, an intrinsic part of decision-making, has been linked to the function of certain key brain regions in humans and nonhuman primates, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), ventral striatum, posterior parietal, and supplementary motor cortex (Platt and Glimcher, 1999; Wunderlich et al., 2009; O'Doherty, 2011; Hunt et al., 2012; Bartra et al., 2013; Clithero and Rangel, 2014). The key question posed in the current study is whether value-related processes in these regions may be modulated by dopamine.

Single-cell recordings from dopamine neurons responding to reward-predicting stimuli have implicated dopamine in the neural coding of the subjective value of stimuli (Fiorillo et al., 2003; Tobler et al., 2005; Roesch et al., 2007). Furthermore, recent pharmacological studies suggested a role of dopamine in the optimal selection of most valuable stimuli within probabilistic learning tasks (Jocham et al., 2011; Shiner et al., 2012; Smittenaar et al., 2012). However, there is a critical distinction between value updating (learning) and value-based decision-making, and these cannot be fully dissociated within probabilistic learning tasks. Whereas both processes are hypothesized to be modulated by dopamine (McClure et al., 2003), the distinct role of dopamine in decision-making, dissociated from learning, has not been experimentally investigated. To address this, we conducted a between-subject, placebo-controlled pharmacological fMRI study in healthy volunteers.

We explored the effects of both a dopamine agonist and an antagonist on the subjective valuation of food items in a Becker-deGroot-Marschak (BDM) mechanism (Becker et al., 1964). The BDM replicates many aspects of second-price auctions and provides a robust means of obtaining subjective values and involves no learning component. It has been used in human neuroscience before (Grether et al., 2007; Plassmann et al., 2007). All items in the auction were well known everyday foods whose value subjects would have acquired through life experience, independent of our experimental manipulation. This enabled us to characterize the impact of dopaminergic modulation on the behavioral and brain processes associated primarily with decision-making.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Forty-seven healthy, right-handed people (23 males, aged 23.8 ± 3.2, body mass index 21.7 ± 1.6 kg/m2; mean ± SD) participated in the study. All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, had no history of psychiatric or other significant medical history, and reported no contraindications to the pharmacological agents or MRI scanning.

The study was approved by the Cambridge East Local Research Ethics Committee (REC 11/EE/0480) and was conducted at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility and the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre in Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written, informed consent.

Study design

In a double-blind, between-subject study, subjects received a single oral dose of either bromocriptine 1.25 mg (dopamine D2 agonist, n = 15), sulpiride 400 mg (D2 antagonist, n = 16), or placebo (n = 16). One subject (from the sulpiride group) did not pay attention to the task and was excluded from the analysis (on >50% of the free trials, the subject placed a bid of £0; when debriefed, she did not express any dislike of the food items on offer or a desire to keep her budget, thus calling into question her understanding of the task). Three additional subjects (1 from each group) were excluded from the fMRI analysis because of severe signal dropout in the frontal lobe, as agreed on visual inspection by the study analysis team. This left 46 datasets (23 males, aged 23.8 ± 3.2, body mass index 21.7 ± 1.6 kg/m2; mean ± SD) for the behavioral analysis and 43 datasets (21 males, aged 23.6 ± 2.9, body mass index 21.5 ± 1.5 kg/m2; mean ± SD) for the fMRI analysis. Subjects' age (F = 0.45, p = 0.64), body mass index (F = 1.02, p = 0.37), or gender (χ2 = 0.04, p = 0.98) did not differ between the treatment groups. In addition to the task described below, participants underwent a number of other cognitive measures, which are not presented here.

Subjects attended the study session in the morning following an overnight fast. They received a standardized breakfast (based on body weight, age, and gender) on the clinical research facility at 8:00 A.M. This was to ensure similar baseline metabolic states across subjects and to minimize pharmacokinetic perturbations related to food and drink.

Bromocriptine and sulpiride have been used in previous studies (Cools et al., 2009; Dodds et al., 2009; Morcom et al., 2010), and are well tolerated at these doses. As bromocriptine can cause nausea [from the bromocriptine Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC), 2012], to maintain the double-blinding and prevent any effects of nausea on performance on a food-related task, all subjects were prophylactically given 10 mg of the antiemetic domperidone, which does not cross the blood–brain barrier (from the domperidone SPC, 2012). Bromocriptine reaches peak plasma levels 1–3 h postdose, with a half-life of ∼15 h (Kvernmo et al., 2006). Sulpiride reaches its maximal plasma concentration ∼3 h postdose, and has a plasma half-life of ∼12 h (Wiesel et al., 1980; Caley and Weber, 1995). The study drug and domperidone were given to all participants at 11:00 A.M. The fMRI acquisition started ∼2.5 h after receiving the drugs (at ∼1:30 pm) to capture the window of maximal drug effect.

fMRI task

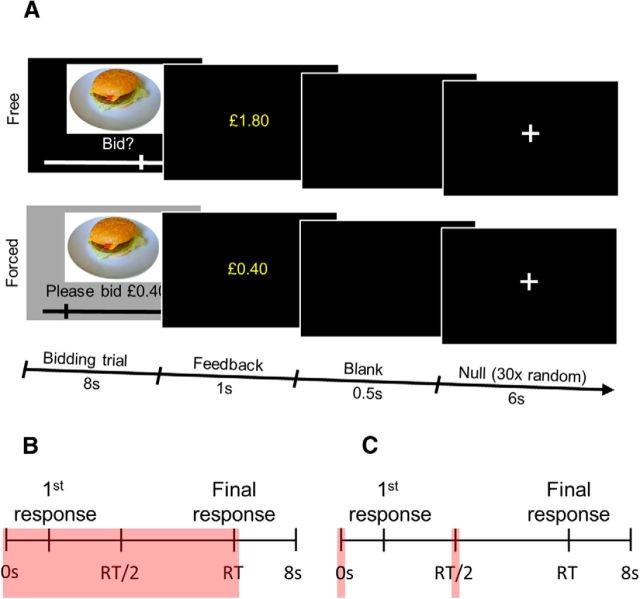

A computerized version of the BDM auction was developed, in which participants could bid for 50 different foods, represented by photographs (Fig. 1A). Participants were given a fixed budget, and the auction procedure incentives participants to place bids as close as possible to their real subjective value.

Figure 1.

Task structure and model specification. A, The auction task featured 50 snack items presented as part of free and forced trials. Free and forced trials, of 8 s duration, were presented in a randomized order. After the bidding trial was over, a 1 s feedback screen showing the final bid was presented. This was followed by a 0.5 s blank screen. On 30 random occasions during the course of the task, a 6 s null trial with a fixation cross was presented after the blank screen. B, fMRI Model 1 schematic. Each bidding trial was modeled as a boxcar function (depicted as a pink rectangle), from the onset of the food stimulus until the bid was confirmed (duration equal to RT). C, fMRI Model 2 schematic. Two time points within each bidding trial were modeled as events within the trial (0 s stick or delta functions, depicted as pink rectangles): an early phase regressor set at the time of food stimulus onset, and a late phase regressor set at a time halfway from the food photo onset to the bid confirmation (RT/2), separately for each trial.

In addition to their study participation fee, before entering the scanner, participants were handed a budget of £3 for bidding. This was physically given to them to ensure they regarded the budget as their own money. They were instructed that on each trial they could place a bid between £0 and £3 for the presented item. Responses were made on a sliding scale that went from £0 to £3 in increments of 20 pence. Participants were told that the computer would bid against them on each trial but the bid would not be disclosed to them. As per the rules of the auction, one trial would be randomly selected at the end of the auction (subjects therefore did not have to spread their £3 budget across different trials, and were instructed to treat every trial as if it were the only one). If their bid for the food item on the selected trial was larger than the computer's, they would win that food item, get a chance to eat it after the scanning session and only have to pay the amount the computer bid (which would be less than their bid) and keep any remaining change. If, however, the computer outbid them or matched their bid, they would not win the food item but would get to keep their £3 budget. Given this setup, the auction is incentive-compatible, i.e., the best strategy is to place a bid close to what one is actually willing to pay. As the actual amount paid is determined by the computer's bid on the selected trial, bidding higher amounts risks having to pay more than one's subjective value. Bidding lower amounts runs the risk of losing the opportunity to win the item (more cheaply than one was prepared to pay for it). These rules were all explicitly stated and emphasized to the subjects as part of the task instructions. Critically, participants were in a hungry state and were told that they could eat any food they won after the scanning session.

Because each trial entails a number of perceptuomotor components, we used an approach taken by Plassmann et al. (2007), by including a control task in which the same 50 foods were presented in “forced” trials (as opposed to the above “free” trials) where subjects were instructed to bid an amount taken from a random distribution of possible bids from £0 to £3, again in 20 pence increments. These trials required participants to engage in all the processes involved in the free trials with the critical difference of requiring no subjective valuation. Moreover, participants were aware that they would not lose money on such trials.

Fifty trials of each trial type (free and forced), of duration 8 s, were presented in a randomized order. The picture of the food was presented throughout the entire 8 s duration of a trial. The initial position of the cursor on the sliding scale varied randomly. Participants placed bids using a standard button box with the first and second buttons serving to move the cursor down or up the sliding value scale in steps of 20 pence, and the third button serving to confirm the final bid and mark the end of the bidding. From this point until the end of the 8 s bidding trial, the cursor could not be moved further. When the 8 s bidding trial was over, a feedback screen showing the final bid was presented (Fig. 1A). If the bid was not confirmed within 8 s, the feedback screen stated, “Not quick enough.” In the analysis, these trials were considered missed trials.

In fact, for practical reasons, the task was set up to ensure that subjects did not win a food item, but instead ended up keeping their £3 budget.

Behavioral analysis

Behavioral data were analyzed using mixed-effects models (nlme package in R; Pinheiro et al., 2014), with subjects as a random effect. Post hoc comparisons, where needed, were done using the multcomp package (Hothorn et al., 2008).

fMRI data acquisition and analysis

All data were acquired on a Siemens Verio scanner operating at 3 tesla with a 192 mm field-of-view at the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre, Cambridge, UK. A total of 570 gradient echo T2*-weighted echo planar images (EPI) depicting blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) contrast were acquired for each participant. The first six images were discarded to avoid T1 equilibration effects. Images comprised 31 slices, each 3 mm thick with a 0.8 mm interslice gap and a 64 × 64 data matrix. Slices were acquired in an ascending interleaved fashion, repetition time = 2000 ms, echo time = 30 ms, flip angle = 78°, axial orientation = oblique. Data were analyzed using statistical parametric mapping in the SPM8 program (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk). Images were realigned then spatially normalized to a standard template and spatially smoothed with an isotropic three-dimensional Gaussian filter (8 mm full-width at half-maximum). The time series in each session were high-pass filtered (with cutoff frequency 1/120 Hz) and serial autocorrelations were estimated using an AR(1) model.

Model 1: brain responses to value across the entire bidding period and its modulation by dopamine.

Each bidding trial was modeled as a boxcar function, from the onset of the food stimulus until the bid was confirmed (duration equal to reaction times, RTs; Fig. 1B). Separate regressors were created for free and forced trials. Free and forced bids were used as parametric modulators of these regressors. Missed trials (in which no bids were selected within 8 s) were modeled as a separate regressor. All regressors were convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function with a temporal derivative. Six motion realignment parameters were included as regressors of no interest.

To examine processes specifically associated with valuation, we calculated the first-level contrasts as the difference between the parametric modulator of free bid in free trials and forced bid in forced trials. Given that, in forced trials subjects implemented instructed bids, these trials should not engage the circuitry of interest to us but they should engage all other nonspecific processes related to valuation. The applied contrast thus corrects for nonspecific effects and enables identification of regions specifically involved in the valuation-based decision process. Single-subject contrast images were then entered into a second-level group analysis, with subjects as a random effect.

At the second level, two analyses were performed:

To explore which brain regions are involved in valuation across all subjects, independent of pharmacological treatment, we computed a one-sample t test on the single-subject contrast coefficients from all 43 participants. The analysis was conducted within a predefined 10-mm-radius sphere in the vmPFC (from the work of Chib et al. (2009)), with a familywise error (FWE) small-volume corrected threshold of p < 0.05. This was based on our a priori hypothesis given the strong evidence implicating this region in value computation. In addition, we explored the existence of value related signals across the whole brain, adopting a threshold of p < 0.05, FWE corrected at the cluster-level. Additionally, for completeness, we explored the existence of brain regions whose neural activity separately correlated with free bids in free trials and forced bids in forced trials. We also explored whether there was a region whose activity tracked the mismatch between free bid and the randomly ascribed forced bid for the same food item during forced trials; this entailed examining the existence of correlation between neural activity during forced trials and a parametric modulator of the difference between the free bid and the randomly ascribed forced bid for same food item. These additional analyses were conducted at the whole-brain level, using a more liberal threshold of p < 0.001, uncorrected.

To explore the effect of the dopaminergic modulation on the neural representation of value, we performed a nondirectional F test (ANOVA). This was again conducted within the vmPFC ROI, applying a small-volume corrected threshold of p < 0.05, and at the whole-brain level, at a more liberal threshold of p < 0.001 uncorrected, k > 20 voxels. This threshold at the whole-brain level was adopted because it is not possible to apply a cluster-level correction for F tests in SPM8 and a voxel-level correction would be too stringent. In case of significant effects, they were further delineated using two-sample t tests at the whole-brain cluster-level and within the vmPFC sphere, at a FWE corrected threshold of p < 0.05.

Model 2: does dopamine have different contributions to different phases of the bidding/valuation process?

This post hoc analysis aimed to establish the temporal specificity of the dopaminergic effects and, in so doing, to relate them to the early (initial valuation) and late (value-dependent action) stages of the bidding process. A modified first-level model was estimated that looked for changes in the correlation of BOLD activity with the bid separately for early and late phases of each trial.

To model the early and late stages of the bidding process, two regressors were created for each subject. These two regressors were modeled as 0 s stick functions: an early period regressor was set at the time of food photo (and trial) onset, and a late period regressor was set at a time halfway from the food photo onset to the bid confirmation (RT/2). This was done separately for each trial (Fig. 1C). Whereas at the first time point no responding took place, at the second time point, participants were responding to select the bid. Missed early and late regressors were modeled as separate 0 s stick functions, with the late time point regressor modeled at 4 s (halfway through the trial). The parametric modulators of bids for early and late time points were the same for a given trial. To identify neural representations of value at each time point, two separate single-subject contrasts were computed: the early neural representation of value as the difference between the parametric modulator of free bid and forced bid at the early time point; and the late neural representation as the difference between the parametric modulator of free bid and forced bid at the late time point.

The two contrast images per each individual were put forward to the second-level group analysis, with subjects as a random effect. At the group level we used a 2 × 3 factorial ANOVA to explore the interaction between time and drug on the neural representation of value. This analysis was confined to a 10-mm-radius sphere around the peak voxel exhibiting the strongest dopaminergic modulation of neural representation of value, established in the previous analysis. The analysis was conducted at a FWE small-volume corrected threshold of p < 0.05.

Results

Behavioral results

Missed trials

Predictably, there were significantly fewer missed trials within the free than in the forced trials (free: 0.48 ± 0.12, mean ± SEM; forced: 1.52 ± 0.27,mean ± SEM; F = 17.49, p = 0.0001); however, this did not differ across groups (trial type-by-group interaction: F = 0.14, p = 0.87).

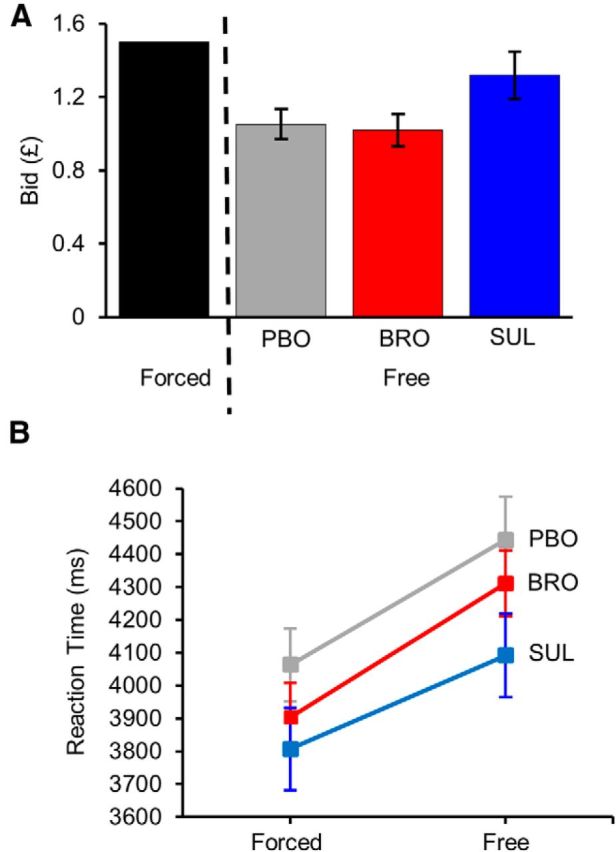

Bid

Despite a clear trend for higher free bids in the sulpiride group (Fig. 2A), the effect of treatment did not reach significance (F = 2.83, p = 0.07). Pairwise comparisons revealed a strongest difference between sulpiride and bromocriptine, however this did not reach significance (sulpiride vs bromocriptine: z = 2.16; p = 0.08; placebo vs bromocriptine: z = 0.23, p = 0.97; sulpiride vs placebo: z = 1.96, p = 0.12; Tukey-corrected for multiple comparisons).

Figure 2.

Behavioral results. A, Average bid by treatment group in the free trial condition. Error bars represent SEM of each subject's average bid. Presented on the same graph is the mean of the uniform distribution of instructed forced bids. B, Average RT by treatment group and trial type. Error bars represent SEM of each subject's average RT.

Free bids were found to be positively correlated with the initial random position of cursor on the bidding scale (t = 6.09, p < 0.0001); however, this did not differ between different treatment groups (initial cursor position-by-treatment group interaction: F = 1.76, p = 0.17). Adding the initial cursor position as the covariate into the model exploring the effect of treatment group on the bid did not change the reported results.

Reaction time

Individual RTs were, of course, dependent on the initial position of the cursor since this would determine how far they were required to move to finalize the selection. There was thus a correlation between starting point and RT (t = 10.15, p < 0.0001). To account for this, the number of button presses made to select the bid was entered as a covariate into the model exploring the effect of trial type and drug treatment on RT. The analysis revealed a significant effect of trial type (F = 398.39, p < 0.0001), with subjects, as expected, being quicker on forced compared with free trials (Fig. 2B). There was no main effect of treatment (F = 1.01, p = 0.37), however there was a significant treatment-by-trial type interaction (F = 3.7, p = 0.025). None of the pairwise comparisons between drug treatments in the free condition reached significance, however, as evident from the plot, there was a trend of shorter RTs under sulpiride compared with placebo and bromocriptine (placebo vs bromocriptine: z = 0.47, p = 0.86; sulpiride vs bromocriptine: z = −1.29, p = 0.39; sulpiride vs placebo: z = −1.78, p = 0.18; Tukey corrected for multiple comparisons). As evident from the plot, the analogous analysis within the forced trials revealed no difference in reaction RTs between drug treatments (placebo vs bromocriptine: z = −0.46, p = 0.89; sulpiride vs bromocriptine z = −0.85, p = 0.67; sulpiride vs placebo: z = −0.41, p = 0.91; Tukey corrected for multiple comparisons).

fMRI results

As described above, two key analyses were performed. Our first analysis treated the entire duration of the bidding (equal to RT, mean RT ± SD = 4.1 ± 1.37 s) as the period of interest to identify regions sensitive to value and dopaminergic modulation (Model 1; Fig. 1B). Next we sought to determine whether in these regions, there were differential effects of dopamine on different aspects of the bidding process (Model 2; Fig. 1C). Model 2 examined whether the drug effects were specific to a particular stage of each trial. Dividing every trial into early and late phases (corresponding approximately to initial valuation and value-dependent action) on the basis of the response made, we explored the interaction between drug, value (bid size), and trial phase (early vs late).

The neural representation of value (Model 1)

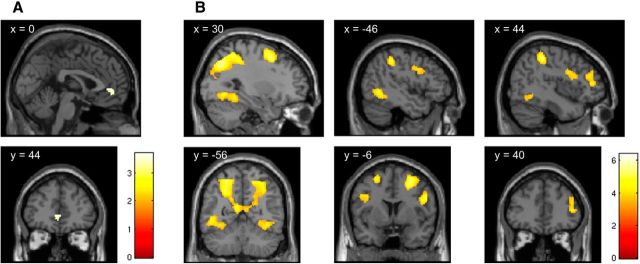

Examination of the brain regions involved in valuation across all study participants revealed activity correlating with subjective value within the predefined region of vmPFC (pFWE < 0.05, small volume corrected; Fig. 3A), consistent with theory and previous work (Bartra et al., 2013; Clithero and Rangel, 2014). Further, several clusters were seen (whole-brain cluster-level pFWE < 0.05) including a large cluster encompassing the left and right posterior parietal cortex [maxima located in the region of intraparietal sulcus (IPS) on both sides] and extending to the left fusiform gyrus and further clusters in middle and inferior frontal gyri bilaterally and in the right fusiform/lingual gyrus (Fig. 3B; Table 1).

Figure 3.

Neural representation of value. Significant areas of activation were rendered onto a standard SPM8 T1 template image, with coronal and sagittal sections presented at the coordinates appropriate for displaying relevant regions. A, The neural representation of value was found within the predefined 10-mm-radius sphere in the vmPFC region (pFWE < 0.05, small-volume corrected). B, Equally, value-coding clusters were found in regions surviving the whole-brain correction at the cluster-level (pFWE < 0.05). These include a large cluster encompassing the left and right posterior parietal cortex (maxima located in the region of IPS on both sides) and extending to the left fusiform gyrus and further clusters in middle and inferior frontal gyri bilaterally and in the right fusiform/lingual gyrus. Full details of the activation foci are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Regions correlated with subjective value

| Region | Side | Cluster size | Peak MN coordinates |

Peak scores |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | Z | T | Z | |||

| Intraparietal sulcus | L/R | 7354 | −26 | −66 | 46 | 6.4 | 5.32 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 425 | −24 | 2 | 58 | 5.75 | 4.91 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | 744 | 25 | −1 | 54 | 5.5 | 4.74 |

| Fusiform gyrus/lingual gyrus | R | 833 | 28 | −64 | −8 | 5.24 | 4.57 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 604 | 50 | 6 | 26 | 4.86 | 4.3 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | 286 | 46 | 42 | 10 | 4.25 | 3.86 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | 248 | −48 | 2 | 34 | 4.1 | 3.74 |

| Anterior cingulate/medial frontal gyrus* | L/R | 81 | 0 | 44 | 2 | 3.71 | 3.43 |

p < 0.05 whole-brain FWE correction for multiple comparisons at the cluster-level (p < 0.001 uncorrected threshold).

*Survives p < 0.05 small-volume FWE correction within a 10 mm sphere around the vmPFC coordinates (−3, 42, −6) from the work of Chib et al. (2009).

For completeness, we conducted two additional analyses. First, we explored the correlation of neural activity with free and forced bids separately. Whereas the neural activity correlating with free bids in free trials mimicked the pattern of neural activity in our main contrast, there was no region, even at a liberal threshold of p < 0.001 uncorrected, whose activity correlated with forced bids in forced trials. This confirms that the effects established in our main contrast were not driven by activity associated with forced trials. Second, we also investigated whether there was a region whose activity tracked the mismatch between free bid and the randomly ascribed forced bid for the same food item during forced trials. That is, we determined whether being forced to make a bid that markedly deviated from how one would normally value a given item was associated with enhanced responses. However, no such region was detected, even at a liberal threshold of p < 0.001 uncorrected.

Dopaminergic drugs modulate the neural response to value in the left and right inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus (Model 1)

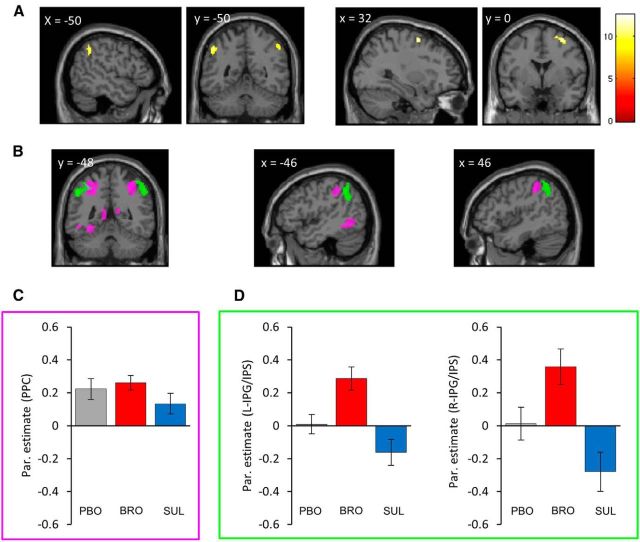

We next explored the effect of the administered dopaminergic drugs on the valuation-dependent brain activity. The ANOVA comprising the three levels of pharmacological treatment found no effect of treatment in the vmPFC (this was also true for a more liberal threshold, p < 0.001 uncorrected). A significant effect of dopaminergic treatment was found in the right middle frontal gyrus and in the left and right inferior parietal gyrus, in close vicinity of the IPS (IPG/IPS; p < 0.001 uncorrected, k > 20 voxels; Table 2; Fig. 4A).

Table 2.

Regions exhibiting a dopaminergic modulation of the neural representation of value

| Region | Side | Cluster size | Peak MNI coordinates |

Peak scores |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | Y | Z | F | Z | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | 55 | 32 | 0 | 58 | 12.62 | 3.86 |

| Inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus | L | 63 | −50 | −50 | 46 | 11.17 | 3.63 |

| Inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus | R | 40 | 52 | −50 | 48 | 9.95 | 3.42 |

p < 0.001 uncorrected, extent k > 20 voxels.

Figure 4.

Dopaminergic modulation of the neural representation of value. Significant areas of activation were rendered onto the standard SPM8 T1 template image, with coronal and sagittal sections presented at the coordinates appropriate for displaying relevant regions. A, Activation areas in the left and right IPG/IPS, and in the right middle frontal gyrus that exhibited an effect of drug on the neural representation of value (p < 0.001 uncorrected, k > 20 voxels). B, Displayed in green are the activation areas in the left and right IPG/IPS in which there was an enhancement of the neural representation of value in the bromocriptine compared with the sulpiride treatment group (pFWE < 0.05, whole-brain corrected at the cluster-level). Value-coding clusters, common to all three treatment groups, are presented in magenta ((pFWE < 0.05, whole-brain corrected at the cluster-level). C, Presented inside the magenta box are the parameter estimates of the neural representation of value averaged per treatment groups, extracted from the large value-coding cluster spanning the left and right posterior parietal cortex (presented in magenta on the images in B). D, Presented inside the green box are the parameter estimates of the neural representation of value averaged per treatment groups, extracted from the left and right IPG/IPS clusters of the bromocriptine versus sulpiride contrast (presented in green on the images in B). Error bars represent SEM. Full details of the activation foci are given in Tables 2 and 3.

To establish more precisely what drove this effect, additional two-sample t-tests were performed. Compared with sulpiride, bromocriptine was associated with a stronger relationship between value and activity in the IPG/IPS bilaterally (corrected for multiple comparisons at the cluster-level, pFWE < 0.05; Table 3; Fig. 4B,D); in other words, it increased the strength of correlation between the bids and the BOLD response. Further t tests between individual pharmacological treatments did not reveal any significant clusters at the same threshold.

Table 3.

Regions with an enhanced neural representation of value under bromocriptine compared with sulpiride

| Region | Side | Cluster size | Peak MNI coordinates |

Peak scores |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | Z | T | Z | |||

| Inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus | L | 494 | −50 | −50 | 46 | 4.66 | 4.14 |

| Inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus | R | 363 | 52 | −50 | 48 | 4.45 | 3.99 |

p < 0.05 whole-brain FWE correction for multiple comparisons at the cluster-level (p < 0.001 uncorrected threshold).

Interestingly, these two clusters were close to the posterior parietal cluster identified in the previous contrast. As can be seen from the parameter estimates (Fig. 4C), there was a trend toward reduced neural representation of value within the sulpiride group in the posterior parietal cluster, however, the clear distinction between the groups was only seen in the L- and R-IPG/IPS clusters.

In summary, we found that the neural response to value is significantly affected by pharmacological manipulation of dopaminergic function in the IPG/IPS region and this effect was driven by the bromocriptine versus sulpiride contrast.

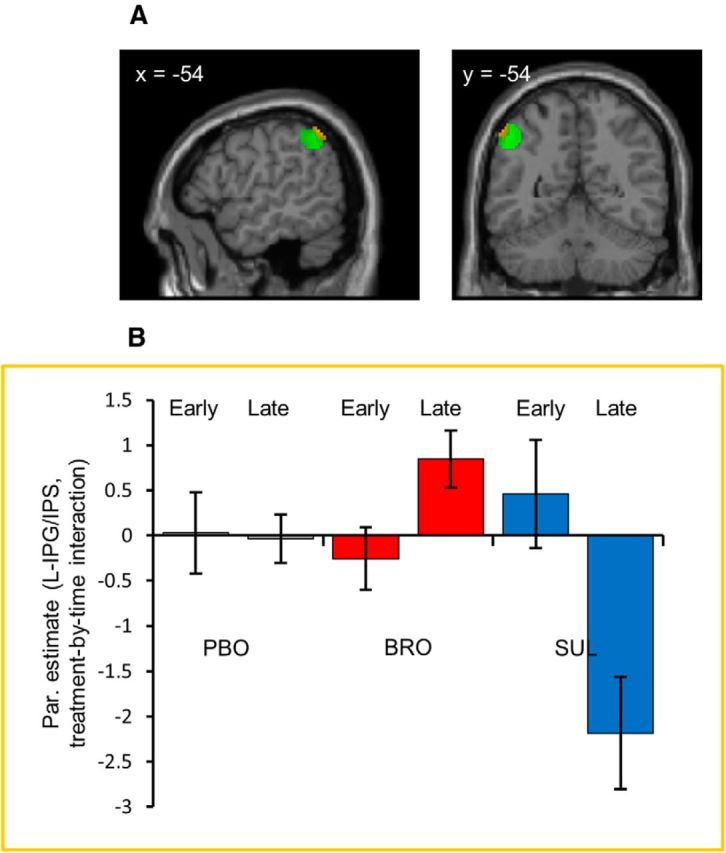

Dopaminergic treatment modulates the neural representation of value in the left inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus during the late stage of valuation (Model 2)

Here, we investigated whether the dopaminergic modulation is specific to the early or late stage of the valuation process. We focused specifically on the regions showing an effect of drug across the whole trial, splitting this trial into early and late phases (with the split-point determined based on time-to-decision for each trial separately). A significant time-by-drug interaction was established in a 10-mm-radius sphere around the peak voxel in the left IPG/IPS demonstrating the strongest effect of dopaminergic treatment in the previous model (pFWE < 0.05, small-volume corrected; Table 4; Fig. 5A). As evident from the parameter estimates extracted from each of six conditions (Fig. 5B), the effect of dopaminergic manipulation on valuation was greater during the later (value-dependent action) phase compared with the earlier (initial valuation) phase. This result suggests that the modulation of strength of correlation between the bids and the BOLD signal in the left IPG/IPS, increasing with bromocriptine and decreasing with sulpiride, becomes more pronounced closer to the point when an appropriate action is used to record the final bid, i.e., when the participant makes a fine-grained decision about whether the bid should be 20 pence more or less, which in the context of our task might indicate a dopaminergic influence on the fine tuning of the valuation process.

Table 4.

Activation peak exhibiting a time-by-treatment interaction in the left IPG/IPS

| Region | Side | Cluster size | Peak MNI coordinates |

Peak scores |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | F | Z | |||

| Inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus | L | 10 | −54 | −54 | 50 | 8.79 | 3.39 |

p < 0.05 small-volume FWE correction within a 10 mm sphere around the peak voxel in the left IPG/IPS (−50, −50, 46) which showed an effect of drug across the entire bidding trial (Model 1).

Figure 5.

Dopaminergic treatment modulates the neural representation of value in the left inferior parietal gyrus/intraparietal sulcus during the late stage of valuation. Coronal (at y = −54 mm to the anterior commissure) and sagittal sections (at x = −54 mm to the left of the midline) from the standard SPM8 T1 template image. A, The analysis was confined to a 10-mm-radius sphere around the voxel in the left IPG/IPS that showed the strongest dopamine-dependent modulation in Model 1, and is depicted here in green. Presented in yellow are the voxels within this sphere showing a significant treatment (placebo, bromocriptine, sulpiride) by time (early, late) interaction. For display purposes, both contrasts are presented at p < 0.01 uncorrected. B, Presented inside the yellow box are the parameter estimates of the neural representation of value for each of the six conditions: treatment (placebo/bromocriptine/sulpiride) and time (early/late). The parameter estimates were extracted from the voxels exhibiting the treatment-by-time interaction within the described sphere (presented in yellow on the image in A). Error bars represent SEM. Full details of the activation foci are given in Table 4.

Discussion

In this pharmacological fMRI study we used the established BDM mechanism with food rewards, in a sample of hungry participants, to assess the role of dopamine in subjective valuation. We characterized the effects of dopaminergic modulation, using both an agonist and an antagonist, demonstrating its role in the coding of value in the IPS. Compared with sulpiride, bromocriptine enhanced the neural representation of value in the IPS. Moreover, a significant drug-by-value-by-trial phase interaction indicated that the dopaminergic modulation of neural response was specific to the late phase of the trials, when an action was needed to record the value.

Although there is rich literature on the role of dopamine in value learning (Schultz et al., 1997; Schultz, 1998; Wise, 2004; Bayer and Glimcher, 2005; Steinberg et al., 2013), there is relatively little exploring its role in value computation during decision-making. Recent studies in healthy adults and patients with Parkinson's disease have partly addressed this using a probabilistic learning/choice task, demonstrating that dopamine biases choice toward more valuable options (Jocham et al., 2011; Shiner et al., 2012; Smittenaar et al., 2012) and enhances the expression of value in the vmPFC (Jocham et al., 2011). However, the learning nature of these tasks prevents a clear dissociation of dopaminergic effects on learning and performance/choice (particularly given that by Jocham et al., (2011), the dopamine-modulated prediction error expressed during the learning phase also predicted choice in the performance phase). Our results concur with these findings, and complement them by demonstrating a dopaminergic component of value computation in response to already well learned items. Furthermore, the realistic nature of the task and the inclusion of highly familiar foods as auction items more closely mimics everyday value computations we make, which compared with choosing between probabilistic stimulus–reward associations, are more complex and are thought to entail integration of various attributes into a single measure of subjective value, which can be then used as input for making choices (Rangel et al., 2008).

Interestingly, although our first analysis (Model 1) replicated previous work in showing value signals in several brain regions including vmPFC (O'Doherty, 2011; Hunt et al., 2012; Bartra et al., 2013; Clithero and Rangel, 2014), only in the IPS was value representation modulated by dopamine. The finding of a dopaminergic effect in the IPS and not in the vmPFC, and the relatively late timing of this signal, suggests that a different dopamine-sensitive value computation is being processed in the IPS. We are cautious about interpreting a null effect in vmPFC but it is worth noting that the association of BOLD activity in this region with value has been generally established at the initial stages of the decision-making process and is thought to serve as an input to later stages of decision-making (Rangel and Clithero, 2013). Conversely, posterior parietal cortex has been implicated as central to action-based decision-making (Platt and Glimcher, 1999; Dorris and Glimcher, 2004; Musallam et al., 2004; Sugrue et al., 2004). Notably, one part of this region, the lateral intraparietal area has been found to represent a spatial map for guiding saccades (Snyder et al., 1997), and to encode the value of rewards associated with individual saccades (Platt and Glimcher, 1999; Dorris and Glimcher, 2004; Sugrue et al., 2004). The parietal reach region analogously represents the movement of forelimbs (Connolly et al., 2003; Scherberger and Andersen, 2007; Baumann et al., 2009), and the firing of these neurons correlates with the expected value of the movement's outcome (Musallam et al., 2004). These findings suggest that these two areas encode the value of movements. Human studies have also related measures of action value to activity in the IPS/posterior parietal cortex (Gershman et al., 2009; Wunderlich et al., 2009; Iyer et al., 2010; Hunt et al., 2012; Chowdhury et al., 2013).

One possibility is that dopaminergic enhancement of the neural representation of value reflects an increase in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the value representation. Evidence for this comes from studies of the decline in dopamine function with aging (for review, see Bäckman et al. (2006)). Neural network simulations modeling age-related decline in dopaminergic function as attenuated gain control of SNR (Li et al., 2001; Eppinger et al., 2011) have suggested a plausible mechanistic link between reduced dopaminergic function, attenuated neural representation of the value of stimuli and impairments in decision-making. Furthermore, studies in older adults demonstrated that the increased BOLD signal temporal variability (Samanez-Larkin et al., 2010) and reduced neural representation of expected value (Samanez-Larkin et al., 2011) were predictive of poorer decision-making. Our results complement these findings by directly showing the effects of dopaminergic modulation on the neural representation of value. Moreover, the fact that the drug modulations occurred late in the trials (i.e., close to the final selection of the bid) suggests that dopamine modulates the dynamic process of fine-tuning the neural representation of value as the basis for completing the decision/action.

Behaviorally, we did not detect an effect of dopaminergic treatment on the magnitude of bids, perhaps as consequence of the relatively mild pharmacological perturbation induced. However, the presence of significant neural alterations in the context of matched behavior offers some advantages to interpreting the former more clearly, in keeping with previous theoretical perspectives (Wilkinson and Halligan, 2004). Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there is no data demonstrating that dopamine increases value in a context dissociated from learning. A more detailed analysis of the RTs revealed that the average time to decide on the size of the bid was reduced in the sulpiride condition, suggestive of decreased deliberation on the value of individual foods. Interestingly, this effect was paralleled by a trend toward larger bids in the sulpiride condition. In fact, the average bid under sulpiride is much closer to the mean bid in the forced condition (Fig. 2A). Given that the bids in the forced condition were taken from a random, uniform distribution, we speculate that sulpiride, and the proposed decrease in SNR of value representation, were associated with more random, less deliberative bids.

Finally, it is noteworthy that part of the posterior parietal region lying in close proximity to the dopamine-dependent value coding region identified in this study has been found to be related to goal-directed behavior (Glascher et al., 2010). Given that dopamine has been implicated in mediating the balance between the habitual and goal-directed systems, with increased dopaminergic activity shifting the behavior toward a more dominant goal-directed control (de Wit et al., 2011, 2012; Wunderlich et al., 2012), and given the importance of valuation in goal-directed behavior, we speculate that our agonist and antagonist drugs shifted this balance in different directions with the former promoting more measured, goal-directed responding and the latter, through reducing value SNR, prompting more rapid responses divorced from goal values. Of course, this is a speculation and our experimental design does not allow us to test it directly.

Certain limitations must be acknowledged. The between-subject design prevented analyses of potential brain-behavior correlations. Further, although pharmacological fMRI is widely used and provides a targeted noninvasive way of investigating neural processes, there are some basic limitations of the approach. Given the limited data on dose and receptor occupancy relationships for these agents, doses, and administration protocols are based on the known pharmacokinetics of these drugs and on previous studies that have successfully used them to perturb dopaminergic function (Mehta et al., 2008; Cools et al., 2009; Dodds et al., 2009; Morcom et al., 2010). Dosages are also limited by what can be deemed clinically tolerable for healthy volunteers. Furthermore, there are studies reporting effects different from our findings; namely, enhanced neural value representation and improvement in performance associated with D2 antagonists, presumably linked to presynaptic autoreceptor effects (Frank and O'Reilly, 2006; Jocham et al., 2011). The preponderance of postsynaptic versus presynaptic effects is believed to vary depending on the exact drug used, its concentration, the basal level of dopamine in the system (Frank and O'Reilly, 2006), as well as on the brain area of the studied effect, given the different distribution of postsynaptic and presynaptic receptors throughout the brain (Kilts et al., 1987). It is not possible to entirely exclude the possibility of autoreceptors effects in our study though the directionally of our effects does instil some confidence that we are seeing predominantly postsynaptic effects.

In summary, we explored the role of dopamine in the neural representation of value without the confound of learning. We investigated the direct role of dopamine in the expression of value that has been already learned through life experience, and whose accurate expression is a requisite of goal-directed behavior. Our results suggest that dopamine enhances the neural representation of value in the IPS. The effect predominates toward the end of the valuation process, at the point where the decision becomes explicit in action. These findings provide a dopamine-dependent mechanism underlying impaired decision-making in healthy individuals and clinical populations with reduced dopamine levels.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the NIHR/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Bernard Wolfe Health Neuroscience Fund (H.Z., E.H., I.S.F., P.C.F.), the Wellcome Trust (N.M., H.Z., M.D.V., E.H., W.S., I.S.F., P.C.F.), the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (E.H., I.S.F.), the European Research Council (M.D.V., W.S.) and the National Institutes of Health Caltech Conte Center (M.D.V., W.S.). We thank all the participants and the staff of the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Bäckman L, Nyberg L, Lindenberger U, Li SC, Farde L. The correlative triad among aging, dopamine, and cognition: current status and future prospects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:791–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartra O, McGuire JT, Kable JW. The valuation system: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value. Neuroimage. 2013;76:412–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MA, Fluet MC, Scherberger H. Context-specific grasp movement representation in the macaque anterior intraparietal area. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6436–6448. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5479-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer HM, Glimcher PW. Midbrain dopamine neurons encode a quantitative reward prediction error signal. Neuron. 2005;47:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GM, DeGroot MH, Marschak J. Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behav Sci. 1964;9:226–232. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res Rev. 1998;28:309–369. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caley CF, Weber SS. Sulpiride: an antipsychotic with selective dopaminergic antagonist properties. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:152–160. doi: 10.1177/106002809502900210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chib VS, Rangel A, Shimojo S, O'Doherty JP. Evidence for a common representation of decision values for dissimilar goods in human ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12315–12320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2575-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury R, Guitart-Masip M, Lambert C, Dayan P, Huys Q, Düzel E, Dolan RJ. Dopamine restores reward prediction errors in old age. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:648–653. doi: 10.1038/nn.3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clithero JA, Rangel A. Informatic parcellation of the network involved in the computation of subjective value. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:1289–1302. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JD, Andersen RA, Goodale MA. FMRI evidence for a “parietal reach region” in the human brain. Exp Brain Res. 2003;153:140–145. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Frank MJ, Gibbs SE, Miyakawa A, Jagust W, D'Esposito M. Striatal dopamine predicts outcome-specific reversal learning and its sensitivity to dopaminergic drug administration. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1538–1543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4467-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit S, Barker RA, Dickinson AD, Cools R. Habitual versus goal-directed action control in Parkinson disease. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;23:1218–1229. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit S, Standing HR, Devito EE, Robinson OJ, Ridderinkhof KR, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Reliance on habits at the expense of goal-directed control following dopamine precursor depletion. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;219:621–631. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2563-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds CM, Clark L, Dove A, Regenthal R, Baumann F, Bullmore E, Robbins TW, Müller U. The dopamine D2 receptor antagonist sulpiride modulates striatal BOLD signal during the manipulation of information in working memory. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;207:35–45. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1634-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorris MC, Glimcher PW. Activity in posterior parietal cortex is correlated with the relative subjective desirability of action. Neuron. 2004;44:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger B, Hämmerer D, Li SC. Neuromodulation of reward-based learning and decision making in human aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1235:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo CD, Tobler PN, Schultz W. Discrete coding of reward probability and uncertainty by dopamine neurons. Science. 2003;299:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1077349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, O'Reilly RC. A mechanistic account of striatal dopamine function in human cognition: psychopharmacological studies with cabergoline and haloperidol. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:497–517. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O'reilly RC. By carrot or by stick: cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science. 2004;306:1940–1943. doi: 10.1126/science.1102941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershman SJ, Pesaran B, Daw ND. Human reinforcement learning subdivides structured action spaces by learning effector-specific values. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13524–13531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2469-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gläscher J, Daw N, Dayan P, O'Doherty JP. States versus rewards: dissociable neural prediction error signals underlying model-based and model-free reinforcement learning. Neuron. 2010;66:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grether DM, Plott CR, Rowe DB, Sereno M, Allman JM. Mental processes and strategic equilibration: an fMRI study of selling strategies in second price auctions. Exp Econ. 2007;10:105–122. doi: 10.1007/s10683-006-9135-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J. 2008;50:346–363. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LT, Kolling N, Soltani A, Woolrich MW, Rushworth MF, Behrens TE. Mechanisms underlying cortical activity during value-guided choice. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nn.3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer A, Lindner A, Kagan I, Andersen RA. Motor preparatory activity in posterior parietal cortex is modulated by subjective absolute value. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jocham G, Klein TA, Ullsperger M. Dopamine-mediated reinforcement learning signals in the striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex underlie value-based choices. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1606–1613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3904-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts CD, Anderson CM, Ely TD, Nishita JK. Absence of synthesis-modulating nerve terminal autoreceptors on mesoamygdaloid and other mesolimbic dopamine neuronal populations. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3961–3975. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-12-03961.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvernmo T, Härtter S, Burger E. A review of the receptor-binding and pharmacokinetic properties of dopamine agonists. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SC, Lindenberger U, Sikström S. Aging cognition: from neuromodulation to representation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:479–486. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01769-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Daw ND, Montague PR. A computational substrate for incentive salience. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:423–428. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta MA, Montgomery AJ, Kitamura Y, Grasby PM. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy levels of acute sulpiride challenges that produce working memory and learning impairments in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0947-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcom AM, Bullmore ET, Huppert FA, Lennox B, Praseedom A, Linnington H, Fletcher PC. Memory encoding and dopamine in the aging brain: a psychopharmacological neuroimaging study. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:743–757. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musallam S, Corneil BD, Greger B, Scherberger H, Andersen RA. Cognitive control signals for neural prosthetics. Science. 2004;305:258–262. doi: 10.1126/science.1097938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv Y, Daw ND, Joel D, Dayan P. Tonic dopamine: opportunity costs and the control of response vigor. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:507–520. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty JP. Contributions of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to goal-directed action selection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1239:118–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessiglione M, Seymour B, Flandin G, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. Nature. 2006;442:1042–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, Sarkar D, R Development Core Team . nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects modelsnlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–110. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Plassmann H, O'Doherty J, Rangel A. Orbitofrontal cortex encodes willingness to pay in everyday economic transactions. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9984–9988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2131-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt ML, Glimcher PW. Neural correlates of decision variables in parietal cortex. Nature. 1999;400:233–238. doi: 10.1038/22268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel A, Clithero JA. The computation of stimulus value in simple choice. In: Glimcher PW, Fehr E, editors. Neuroeconomics: decision making and the brain. 2nd edition. New York: Academic; 2013. pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel A, Camerer C, Montague PR. A framework for studying the neurobiology of value-based decision making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:545–556. doi: 10.1038/nrn2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. A role for mesencephalic dopamine in activation: commentary on Berridge (2006) Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:433–437. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch MR, Calu DJ, Schoenbaum G. Dopamine neurons encode the better option in rats deciding between differently delayed or sized rewards. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1615–1624. doi: 10.1038/nn2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Kuhnen CM, Yoo DJ, Knutson B. Variability in nucleus accumbens activity mediates age-related suboptimal financial risk taking. J Neurosci. 2010a;30:1426–1434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4902-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Wagner AD, Knutson B. Expected value information improves financial risk taking across the adult life span. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2011;6:207–217. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherberger H, Andersen RA. Target selection signals for arm reaching in the posterior parietal cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2001–2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4274-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner T, Seymour B, Wunderlich K, Hill C, Bhatia KP, Dayan P, Dolan RJ. Dopamine and performance in a reinforcement learning task: evidence from Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2012;135:1871–1883. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smittenaar P, Chase HW, Aarts E, Nusselein B, Bloem BR, Cools R. Decomposing effects of dopaminergic medication in Parkinson's disease on probabilistic action selection: learning or performance? Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:1144–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LH, Batista AP, Andersen RA. Coding of intention in the posterior parietal cortex. Nature. 1997;386:167–170. doi: 10.1038/386167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg EE, Keiflin R, Boivin JR, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Janak PH. A causal link between prediction errors, dopamine neurons and learning. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:966–973. doi: 10.1038/nn.3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue LP, Corrado GS, Newsome WT. Matching behavior and the representation of value in the parietal cortex. Science. 2004;304:1782–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1094765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler PN, Fiorillo CD, Schultz W. Adaptive coding of reward value by dopamine neurons. Science. 2005;307:1642–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1105370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel FA, Alfredsson G, Ehrnebo M, Sedvall G. The pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral sulpiride in healthy human subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;17:385–391. doi: 10.1007/BF00558453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D, Halligan P. The relevance of behavioural measures for functional-imaging studies of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nrn1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich K, Rangel A, O'Doherty JP. Neural computations underlying action-based decision making in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17199–17204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901077106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich K, Smittenaar P, Dolan RJ. Dopamine enhances model-based over model-free choice behavior. Neuron. 2012;75:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]