Abstract

BACKGROUND

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) is a widely used biomarker in pancreatic cancer. There is no consensus on the interpretation of the change in CA19-9 serum levels and its role in the clinical management of patients with pancreatic cancer.

METHODS

Individual patient data from 6 prospective trials evaluating gemcitabine-containing regimens from 3 different institutions were pooled. CA19-9 values were obtained at baseline and after successive cycles of treatment. The objective of this study was to correlate a decline in CA19-9 with outcomes while undergoing treatment.

RESULTS

A total of 212 patients with locally advanced (n = 50) or metastatic (n = 162) adenocarcinoma of the pancreas were included. Median baseline CA19-9 level was 1077 ng/mL (range, 15–492,241 ng/mL). Groups were divided into those levels below (low) or above (high) the median. Median overall survival (mOS) was 8.7 versus 5.2 months (P = .0018) and median time to progression (mTTP) was 5.8 versus 3.7 months (P = .082) in the low versus high groups, respectively. After 2 cycles of chemotherapy, up to a 5% increase versus ≥ 5% increase in CA19-9 levels conferred an improved mOS (10.3 vs 5.1 months, P = .0022) and mTTP (7.5 vs 3.5 months, P = 0.0005).

CONCLUSIONS

In patients who have advanced pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine-containing regimens baseline CA19-9 is prognostic for outcome. A decline in CA19-9 after the second cycle of chemotherapy is not predictive of improved mOS or mTTP; thus, CA19-9 decline is not a useful surrogate endpoint in clinical trials. Clinically, a ≥ 5% rise in CA19-9 after 2 cycles of chemotherapy serves as a negative predictive marker.

Keywords: pancreatic, gemcitabine, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, outcomes, predictive, prognostic

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is universally lethal, with limited treatment options, and response to currently available chemotherapy remains low. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States, yet it is only the tenth most frequent site of newly diagnosed cancer.1 The radiologic evaluation for response in pancreatic cancer is limited by the desmoplastic nature of the disease.2,3 As patients progress on first-line therapy, there is a rapid decline in their Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, which limits the options available for second-line treatment. Therefore, identifying a biomarker that could detect treatment failure more reliably or consistently than radiologic changes could potentially serve as a clinical marker for response to therapy in clinical settings or as a surrogate endpoint for clinical trials. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) is a sialylated Lewis (Lea) blood-group antigen first defined by the monoclonal antibody 1116 NS 19-9 by Koprowski et al,4 and is found to be elevated in more than 80% of patients who have advanced pancreatic cancer.5 At least 5% of the population and 10% of Caucasians are of the Lea–b– phenotype, and thus negative for Lewis blood-group antigen by inheritance; in addition, increased rates of Lea–b– are present in the pancreatic cancer population.6 These patients are part of the 15% to 20% of patients who will never demonstrate an elevation in CA19-9,7 even in the face of advanced disease. Regardless, it remains the most widely used clinical biomarker in pancreatic cancer, despite being open to multiple interpretations.8

Numerous studies have evaluated CA19-9 with respect to its value both as a prognostic and predictive marker. The prognostic value of baseline CA19-9 has been demonstrated multiple times over, with lower levels of CA19-9 associated with improved outcomes.9–14 Similarly, others have suggested that a treatment-related decline in serum CA19-9 is predictive of response to treatment. The first of these studies to show a significant correlation established a 15% decline from baseline as predictive of improved outcomes.15 Since that time, declines of 20% and 50% have agreed with this premise.10,11,16–18 More recently, 2 publications have found that larger declines, eg, 89% versus 50% decline, predict improved outcomes.12,19 However, the true magnitude of decline that remains predictive has not been clearly defined. In addition, other authors have reported that a decline in CA19-9 from baseline levels is not a useful predictive marker.13,14 The goals of this pooled analysis are to confirm the prognostic value of baseline CA19-9 and to explore the role of decline in CA19-9 from baseline as an early predictive biomarker for improved outcome in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who are receiving gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This study involved an analysis of prospectively collected individual patient data pooled from 6 phase 2 trials examining gemcitabine-containing regimens in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. The studies were conducted at the Arthur G. James Cancer Center at The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; The Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan; and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. These studies were approved by the ethics board of all respective institutions.20–25

Inclusion Criteria

To be eligible for these 6 studies, all patients were required to have a histological or cytological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas that was clinically locally advanced or metastatic. All patients were required to have a performance status of 0 to 2, a life expectancy of 3 months or greater and normal organ function defined as a lack of hematologic, hepatic, or renal dysfunction. Exclusion criteria were similar across the studies, including pregnancy and/or active malignancy within the preceding 5 years except for adequately treated basal cell, squamous cell skin cancer, or in situ cervical cancer. All patients provided signed informed consent in accordance with the institutional Human Investigational Committee guidelines prior to enrollment on the respective studies. Serum CA19-9 samples were obtained at baseline and after each cycle of treatment in all studies.

Patients

Individual patient data for 212 patients were collated into a single database, from which all our data were obtained. Patients were not included in the final analyses if 1 of 4 pieces of data were missing: baseline CA19-9 levels, CA19-9 levels after the first or second cycle, and documented progression status. Patients were also excluded from our analysis if their baseline and all subsequent CA19-9 values were ≤ 15.

Because of missing data from the databases, fewer patients were included in the analysis of predictive value of CA19-9 decline after the second cycle of treatment; 104 were included for mOS determination and 98 were included for mTTP.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics were summarized descriptively. For each patient, baseline CA19-9 level was dichotomized by the sample median value. The maximum percent change was obtained using available serial CA19-9 measures. The percent change in CA19-9 from baseline to the first and the second cycle was calculated separately. To explore the effect of these CA19-9 variables on the time-to-event endpoints (overall survival and time to progression), various cutoffs were used to categorize the patients into “high” and “low” groups. We selected cutoffs of 75% decline, 50% decline, 25% decline, no decline, and 5% increase. The log-rank test was used to generate the P values, and the Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate the hazard ratios. Median time-to-event was estimated together with its 95% confidence interval for each subgroup. Similar analyses were conducted to examine the effect of other variables (sex, disease status, performance status, and so forth). In addition, to characterize the predictive accuracy of the baseline CA 19-9 or the percent change from the baseline to the first and second cycle for the survival outcomes, we calculated the area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve for these continuous variables following the approach proposed by Harrell et al.26 The R function rcorr.cens in the Hmisc library (freeware statistical package R, version 2.13.0) was used for this portion of the analysis. All other statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographics

Patient characteristics (N = 212) are listed in Table 1. The median age was 59 years (range, 28–90 years), and 123 patients were female and 89 male. A total of 162 had metastatic disease and 50 had locally advanced disease. A total of 196 patients had performance status of 0 or 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics (n = 212)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y (Median, Range) | 59 (28–90) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 123 (58%) |

| Male | 89 (42%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 177 (83%) |

| African American | 32 (15%) |

| Other | 3 (2%) |

| Disease status | |

| Metastatic | 162 (76%) |

| Locally advanced | 50 (24%) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status | |

| 0–1 | 196 (92%) |

| ≥2 | 6 (8%) |

| Regimen received | |

| Gemcitabine/cisplatin/5-fluorouracil23 | 47 (22%) |

| Gemcitabine/5-fluorouracil/bevacizumab20 | 43 (20%) |

| Gemcitabine/cisplatin21 | 42 (20%) |

| Gemcitabine/etanercept25 | 37 (18%) |

| Gemcitabine/cisplatin/celecoxib24 | 22 (10%) |

| Gemcitabine/docetaxel/capecitabine22 | 21 (10%) |

CA 19-9 as a Prognostic Indicator

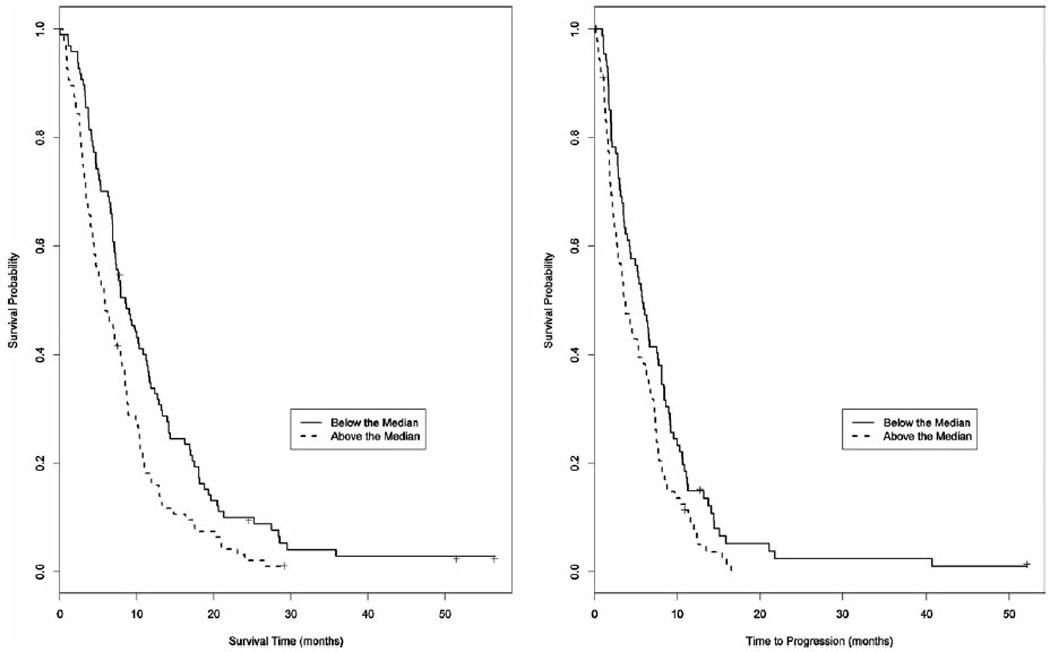

The median baseline CA19-9 level was 1077 ng/mL (range, 2–492,241 ng/mL). Those patients with baseline CA19-9 above the median showed worse outcomes when compared to those with values below the median. The median overall survival (mOS) rose from 5.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.5–8 months) to 8.7 months (95% CI, 7.3–11.2 months) (P = .0018), and median time to progression (mTTP) rose from 3.7 months (95% CI, 2.7–6.1 months) to 5.8 months (95% CI, 4.3–8.1 months) (P = .082) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Median overall survival (mOS) and median time to progression (mTTP) correlated with baseline CA19-9 above or below the median value of 1077 ng/mL. mOS: 5.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.5–8 months) versus 8.7 months (95% CI, 7.3–11.2 months) (P = .0018). mTTP: 3.7 months (95% CI, 2.7–6.1 months) versus 5.8 months (95% CI, 4.3–8.1 months) (P = .082).

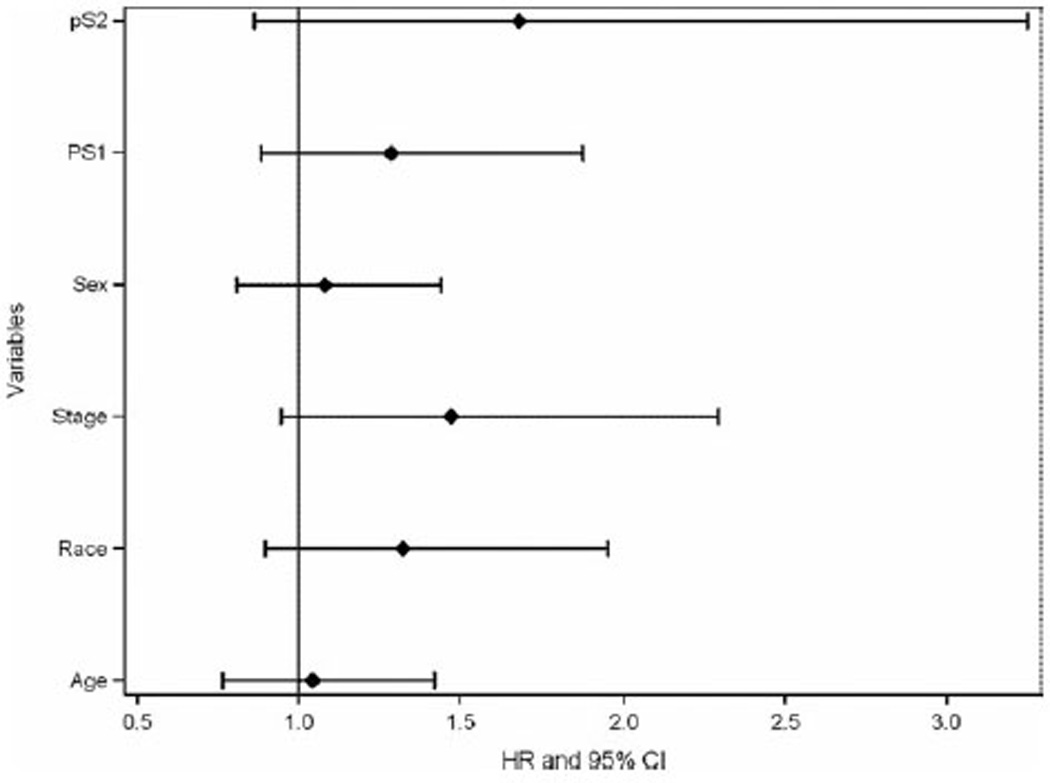

We also performed single-variable analyses of other possible prognostic factors including age, sex, race, performance status, and stage (locally advanced vs metastatic). None of those reached statistical significance, with the hazard ratio including 1 in all comparisons (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Single variable analyses of possible prognostic markers. All variables examined were nonsignificant, with the hazard ratio (HR) including 1 in all comparisons. CI indicates confidence interval; PS, performance status.

CA19-9 as a Predictor for Outcome With Gemcitabine-Containing Chemotherapy

The predictive value in CA19-9 level changes from baseline after the second cycle of chemotherapy was evaluated using various cutoffs. Declines of 25%, 50%, and 75% from baseline were predictive of improved outcome (Table 2). We found that any decline, regardless of magnitude, was similarly predictive for improved outcome compared to no decline with mOS of 10.3 months (95% CI, 8.7–11.7 months) versus 5.2 months (95% CI, 4.5–7.4 months) (P = .0036) and mTTP of 7.6 months (95% CI, 6.4–8.4 months) versus 3.9 months (95% CI, 2.6–5.3 months) (P = .0091) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment-Related Outcomes and Change in CA19-9 Levels From Baseline With 95% Confidence Interval and P Value

| CA19-9 Change from Baseline to Cycle 2 |

mOS (mo) | 95% CI | N | P | mTTP (mo) | 95% CI | n | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥75% Decline | 11.2 | 5.4–21.1 | 17 | .034 | 7.5 | 3.7–11.5 | 17 | .12 |

| <75% Decline | 8.5 | 7.2–10.2 | 87 | 5.4 | 4.2–7.7 | 81 | ||

| ≥50% Decline | 10.7 | 8.7–13.2 | 44 | .049 | 7.7 | 7–9.6 | 43 | .026 |

| <50% Decline | 7.6 | 5.2–8.9 | 60 | 4.3 | 3.3–6 | 55 | ||

| ≥25% Decline | 10.4 | 8.8–13 | 58 | .003 | 7.5 | 6.3–8.8 | 55 | .028 |

| <25% Decline | 7 | 4.8–8.9 | 46 | 4.3 | 3.1–5.4 | 43 | ||

| >0% Decline | 10.3 | 8.8–11.5 | 73 | .002 | 7.5 | 6.3–8.4 | 69 | .0028 |

| ≤0% Decline | 5.1 | 4.2–7.4 | 31 | 3.7 | 2.6–8.4 | 29 | ||

| <5% Increase | 10.3 | 8.8–11.3 | 76 | .002 | 7.6 | 6.4–8.4 | 72 | .0006 |

| ≥5% Increase | 5.1 | 3.7–7 | 28 | 3.5 | 2–4.3 | 26 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; mOS, median overall survival; TTP, time to progression.

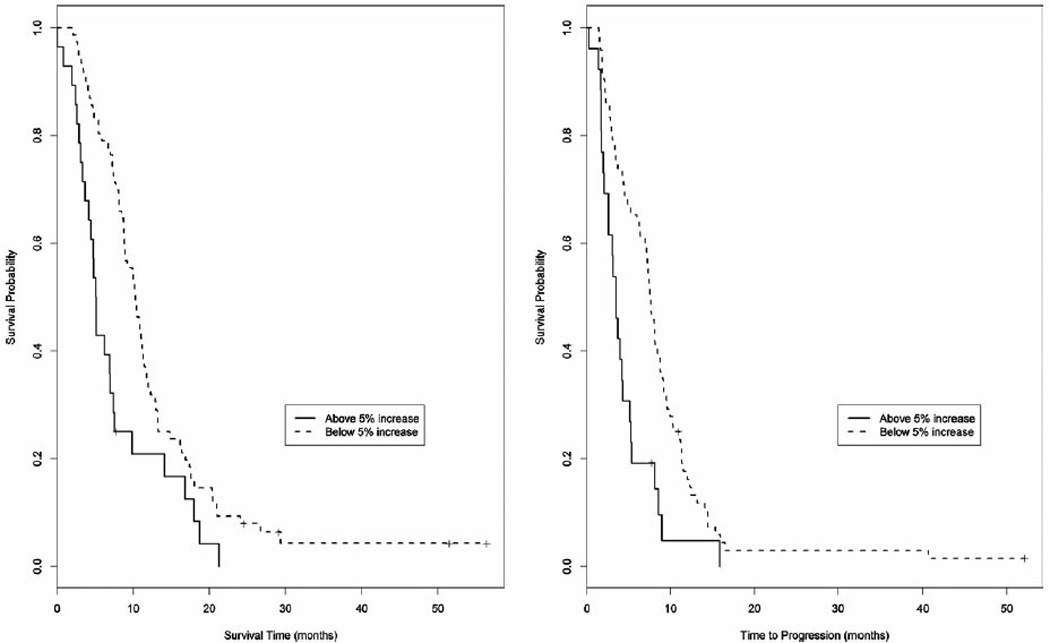

More interestingly, we found that a < 5% increase in CA19-9 levels from baseline remained strongly predictive of improved outcome with mOS of 10.3 months (95% CI, 8.8–11.3 months) versus 5.1 months (95% CI, 3.7–7 months) (P = .002) and mTTP of 7.6 months (95% CI, 6.4–8.4 months) versus 3.5 months (95% CI, 2–4.3 months) (P = .0006) (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Median overall survival (mOS) and (b) median time to progression (mTTP) when correlated with an increase in CA19-9 from baseline of < 5% or ≥ 5% after the second cycle of gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy. mOS of 10.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.8–11.3 months) versus 5.1 months (95% CI, 3.7–7 months) (P = .0022). mTTP of 7.6 months (95% CI, 6.4–8.4 months) versus 3.5 months (95% CI, 2–4.3 months) (P = .0006).

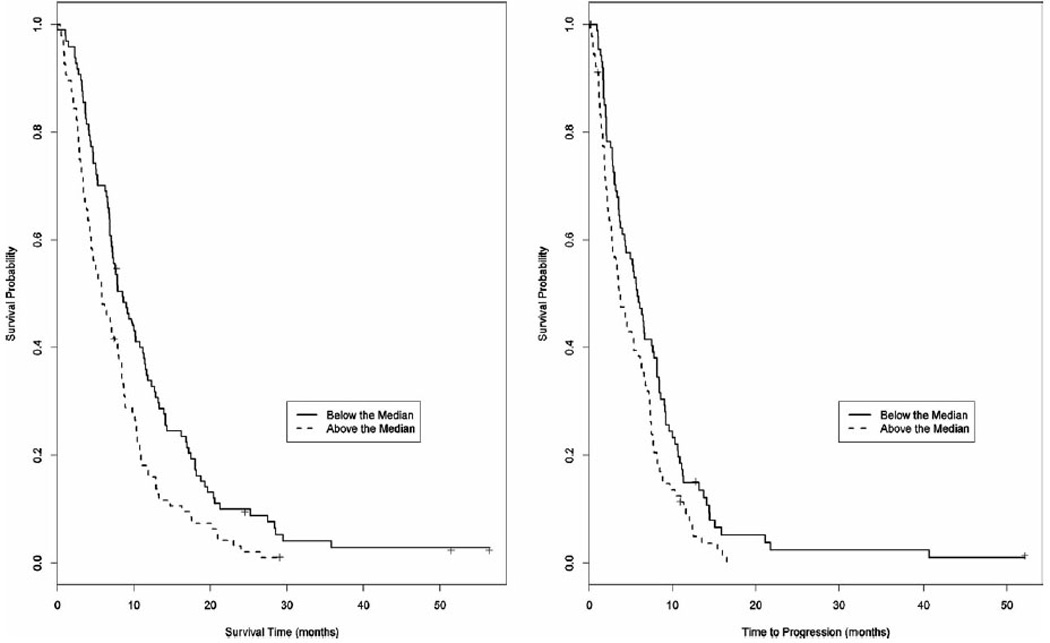

The change in CA19-9 levels from baseline to the first cycle (Fig. 4) did not predict as strongly for improved outcome. Our data revealed a significant improvement in mOS of 9.2 months (95% CI, 7.7–10.9months) versus 6.5 months (95% CI, 4.8–8.1 months) (P = .043) if the CA19-9 declined or rose by < 5%. The mTTP showed a trend toward improvement with 6.6months (95%CI, 5.3–7.5 months) versus 3.7 months (95% CI, 2.7–5.2 months) (P= .197) if the CA19-9 declined or rose by < 5%.

Figure 4.

(a) Median overall survival (mOS) and (b) median time to progression (mTTP) when correlated with an increase in CA19-9 from baseline of < 5% or ≥ 5% after the first cycle of gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy. mOS of 9.2 months (95% CI, 7.7–10.9 months) versus 6.5 months (95% CI, 4.8–8.1 months) (P = .043). mTTP of 6.6 months (5.3–7.5 months) versus 3.7 months (2.7–5.2 months) (P = .197).

We performed an ROC analysis of our data (Table 3). Using baseline CA19-9, the area under the curve (AUC) for OS was 0.424 (95% CI, 0.373–0.476) and for TTP was 0.493 (95% CI, 0.372–0.486). Using the percent change in CA19-9 after cycle 1, the AUC for OS was 0.554 (95% CI, 0.493–0.608) and for TTP was 0.556 (95% CI, 0.493–0.619). Using the percent change in CA19-9 after cycle 2, the AUC for OS was 0.63 (95% CI, 0.561–0.699) and for TTP was 0.618 (95% CI, 0.553–0.683).

Table 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis

| OS (AUC) |

95% CI |

TTP (AUC) |

95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CA19-9 | 0.576 | 0.524–0.627 | 0.571 | 0.514–0.628 |

| Cycle 1 Δ CA19-9 | 0.551 | 0.493–0.608 | 0.556 | 0.493–0.619 |

| Cycle 2 Δ CA19-9 | 0.63 | 0.561–0.699 | 0.618 | 0.553–0.683 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operator characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; Δ, change in CA19-9 level; OS, overall survival; TTP, time to progression.

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a universally lethal cancer for which chemotherapy offers limited benefit.8 Standard imaging techniques are limited due to the desmoplastic response surrounding the tumor.2,3 In this context, a surrogate marker for clinical outcomes of survival and progression in pancreatic cancer would allow for improved and timely decisions regarding treatment and help facilitate new drug development. CA19-9 has been put forth as such a surrogate marker. It has been shown to correlate well with objective response,27 and is widely used as a tool in clinical decision-making. In addition, early phase clinical trials often rely on reported declines in CA19-9 levels to support their hypothesis of treatment efficacy.28–32 However, the reliability of CA19-9 for this use has not been conclusively demonstrated. The cutoff for interpretation of what represents a significant change in CA19-9 in response to chemotherapy has never been established or validated, despite multiple attempts at defining it.10–12,15–19

Multiple groups have published their findings on both the prognostic value of baseline CA19-9 and the predictive value of a decline in CA19-9 levels.9–19 Universally, the studies have included patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who maintain a performance status of ≤ 2. The published body of literature consists of retrospectively and prospectively collected data in trials with patient populations ranging from n = 28 to n = 319. Of the cited works, the average number of patients included in the analysis of baseline CA19-9 as a prognostic marker is n = 107. The average number of patients included in the analysis of decline in CA19-9 as a predictive marker is n = 89.

Numerous studies have reported positively on the prognostic value of CA19-9 in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer treated with chemotherapy.9–14 In each of these studies, the median value of baseline CA19-9 among patients was used as the divider between “high” and “low” groups. With the exception of 1 study, which reported a median value of “about 2000 U/mL”,13 the median values ranged from 958 U/mL in the study by Maisey et al10 to 1212 U/mL in Saad et al.11 Our median of 1077 U/mL corresponds well to these previous studies, and confirms the prognostic significance of baseline CA19-9 on progression and survival. Based on the consistent results of these various studies, we conclude that a baseline CA19-9 level of approximately 1100 U/mL represents a reasonable prognostic cutoff value. We also showed that this prognostic significance was unrelated to age, sex, race, performance status, and/or stage, which improves the reliability of our findings. Because there were no other significant prognostic factors when a univariate analysis was used, a multivariate analysis was not performed. Given our confirmatory results, we conclude that baseline CA19-9 should be used as a stratification factor in new drug development trials for pancreatic cancer. In addition, CA19-9 levels may be used in clinical application to provide newly diagnosed patients with a better understanding of their prognosis; those with baseline CA19-9 levels < 1100 U/mL will have an mOS nearly 50% longer than those whose baseline is > 1100 U/mL (8.7 months instead of 5.9 months). In addition, those with lower CA19-9 levels will have an mTTP that more than doubles, from 2.7months to 6.1 months.

The predictive value of a decline of CA19-9 in response to chemotherapy was first reported in 1998 when one study demonstrated that a decline in CA19-9 of 15% from baseline was predictive for improved outcomes.15 Further studies confirmed this by showing that a decline of greater than 20% was predictive of response.10,16,18 Two other studies found positive correlations between outcomes and a decline of at least 50%.11,17 More recent studies suggested that a larger degree of decline, 75% or 89%, respectively, are predictive of more significant improvements in outcomes.12,19 Yet, in contrast, another study found that there was not a correlation between decline in CA19-9 and outcomes when using a cutoff of 50% decline from baseline.13 In addition, the report from a recent randomized study demonstrated the prognostic value of CA19-9, but found that a decline of 25% or 50% from that baseline was not predictive of outcomes.14 The timing of CA19-9 measurement was also found to vary across studies. One recent publication suggests that a 20% decline from baseline measured after the first cycle of gemcitabine-containing therapy was not predictive of outcome.9 Two other studies with conflicting results suggest that a 50% decline after the second cycle was not significant in one study, but a 20% decline was actually significant in the other one.13,18 The cutoffs used for dichotomization in this study were chosen to demonstrate that our data was consistent with the various previously published cutoffs, while at the same time showing that the trend toward improved outcomes continued to be seen at no change and even a slight increase in CA19-9.

Our results clarify the role of CA19-9 decline early in the course of treatment of pancreatic cancer. The majority of published studies evaluated CA19-9 nadir levels at any point while on trial, which arguably limits the predictive significance of the findings.10–12,18,19 A more meaningful analysis should limit the significance of CA19-9 level changes to findings in the first 2 cycles of therapy, given that most studies restage patients according to this timing. Unlike other studies, we found degree of decline in CA19-9 level to be a negative rather than a positive predictor of outcome when we dichotomized the data as done in all of the previous studies. Our data does not support the conclusion that a > 15% drop in CA19-9 is predictive of improved outcomes. We showed that regardless of the amplitude of the drop, and even with a slight (5%) increase in CA19-9, declining levels remained predictive of an improved outcome. We went a step further, using ROC analysis to evaluate the strength and significance of change in CA19-9 levels. In this analysis, AUC values of < 0.8 are not considered to be useful.26,33 In our study, the AUC values for change in CA19-9 levels at either cycle 1 or cycle 2 were well below this level, supporting our stance that change in CA19-9 level is not a good predictor of response and that no “best-fit” cutoff exists. Therefore, CA19-9 level changes lack significant positive predictive power for outcome and should not be used to make go or no-go decisions about advancing early agents into large prospective trials in pancreatic cancer. Rather, our study suggests that changes after the second but not the first cycle may only serve as a negative predictor for outcome.

Unlike meta-analyses, a pooled analysis such as our study includes individual patient data improving on the strength and statistical significance of the final results. Our study is also one of the larger studies described to date. Despite that, our study certainly has a number of limitations, one of which is the number of patients excluded from the final analyses due to data missing from the pooled data, although the rate of dropout is very comparable to that of other published studies.10,13 From an initial pool of 212 patients, only 104 and 98 were included in the evaluation of mOS or mTTP, respectively, as related to CA19-9 decline at cycle 2. Reasons for exclusion from the final analysis were the absence of baseline CA19-9 levels and missing CA19-9 values after cycle 1 and cycle 2 (probably due to early progression of disease). Another possible limitation relates to the heterogeneity of the patients and the chemotherapy regimens included across the different studies, although all are gemcitabine-based. As stated, however, we did not find any significant difference between the different study populations. In addition, multiple studies have shown that the addition of included agents to the gemcitabine backbone does not affect outcome.34–39 However, newer, more effective therapies could change the predictive value of a decline in CA19-9.

In conclusion, a baseline CA19-9 level cutoff of 1100 ng/mL may serve as a prognostic marker in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who receive gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy. Our results also suggest that CA19-9 level is not a useful surrogate endpoint for go or no-go decisions in clinical trials, because it has a low positive predictive value. However, in the clinical setting, a ≥ 5% rise in CA19-9 after 2 cycles of chemotherapy can serve as a negative predictive marker. As such, it may serve as an adjunct for clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

No specific funding was disclosed.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

The authors made no disclosure.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothenberg ML, Abbruzzese JL, Moore M, Portenoy RK, Robertson JM, Wanebo HJ. A rationale for expanding the endpoints for clinical trials in advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;78(3 suppl):627–632. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960801)78:3<627::AID-CNCR43>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brambs HJ, Claussen CD. Pancreatic and ampullary carcinoma. Ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and angiography. Endoscopy. 1993;25:58–68. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koprowski H, Herlyn M, Steplewski Z, Sears HF. Specific antigen in serum of patients with colon carcinoma. Science. 1981;212:53–55. doi: 10.1126/science.6163212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeck S, Stieber P, Holdenrieder S, Wilkowski R, Heinemann V. Prognostic and therapeutic significance of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 as tumor marker in patients with pancreatic cancer. Oncology. 2006;70:255–264. doi: 10.1159/000094888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Rosen A, Linder S, Harmenberg U, Pegert S. Serum levels of CA 19-9 and CA 50 in relation to Lewis blood cell status in patients with malignant and benign pancreatic disease. Pancreas. 1993;8:160–165. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tempero MA, Uchida E, Takasaki H, Burnett DA, Steplewski Z, Pour PM. Relationship of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and Lewis antigens in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5501–5503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellanos E, Berlin J, Cardin DB. Current treatment options for pancreatic carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13:195–205. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammad N, Heilbrun LK, Philip PA, et al. CA19-9 as a predictor of tumor response and survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010;6:98–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maisey NR, Norman AR, Hill A, Massey A, Oates J, Cunningham D. CA19-9 as a prognostic factor in inoperable pancreatic cancer: the implication for clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:740–743. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saad ED, Machado MC, Wajsbrot D, et al. Pretreatment CA 19-9 level as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2002;32:35–41. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:32:1:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reni M, Cereda S, Balzano G, et al. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 change during chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:2630–2639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess V, Glimelius B, Grawe P, et al. CA 19-9 tumour-marker response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer enrolled in a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:132–138. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasan HS, Springett GM, Chodkiewicz C, et al. CA 19-9 as a biomarker in advanced pancreatic cancer patients randomised to gemcitabine plus axitinib or gemcitabine alone. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1162–1167. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gogas H, Lofts FJ, Evans TR, Daryanani S, Mansi JL. Are serial measurements of CA19-9 useful in predicting response to chemotherapy in patients with inoperable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas? Br J Cancer. 1998;77:325–328. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halm U, Schumann T, Schiefke I, Witzigmann H, Mössner J, Keim V. Decrease of CA 19-9 during chemotherapy with gemcitabine predicts survival time in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1013–1016. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stemmler J, Stieber P, Szymala AM, et al. Are serial CA 19-9 kinetics helpful in predicting survival in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin? Onkologie. 2003;26:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000072980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziske C, Schlie C, Gorschlüter M, et al. Prognostic value of CA 19-9 levels in patients with inoperable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas treated with gemcitabine. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1413–1417. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko AH, Hwang J, Venook AP, Abbruzzese JL, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA. Serum CA19-9 response as a surrogate for clinical outcome in patients receiving fixed-dose rate gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:195–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin LK, Li X, Kim SE, et al. A multi-center phase II study of the combination of bevacizumab, fixed dose rate gemcitabine, and infusional 5-fluorouracil in patients with advanced pancreas cancer. Proceedings of the 100th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; April 18–22, 2009; Denver, CO. Philadelphia, PA: AACR; 2009. Abstract 4500. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philip PA, Zalupski MM, Vaitkevicius VK, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:569–577. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<569::aid-cncr1356>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill ME, Li X, Kim S, et al. A phase I study of the biomodulation of capecitabine by docetaxel and gemcitabine (mGTX) in previously untreated patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:511–517. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Rayes BF, Zalupski MM, Shields AF, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine, cisplatin, and infusional fluorouracil in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2920–2925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Rayes BF, Zalupski MM, Shields AF, et al. A phase II study of celecoxib, gemcitabine, and cisplatin in advanced pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:583–590. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosuri KV, Bekaii-Saab TS, Bender J, et al. Disrupting TNF signaling in pancreatic cancer: A phase I/II clinical study in patients with advanced disease [Abstract]. Proceedings of the 2005 ASCO Annual Meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(suppl) abstract 4103. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong D, Ko AH, Hwang J, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA. Serum CA19-9 decline compared to radiographic response as a surrogate for clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer receiving chemotherapy. Pancreas. 2008;37:269–274. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31816d8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, et al. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548–4554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mamon HJ, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Cancer and Leukemia Group B.A phase 2 trial of gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, and radiation therapy in locally advanced nonmetastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 80003. Cancer. 2011;117:2620–2628. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sudo K, Yamaguchi T, Nakamura K, et al. Phase II study of S-1 in patients with gemcitabine-resistant advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:249–254. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipton A, Campbell-Baird C, Witters L, Harvey H, Ali S. Phase II trial of gemcitabine, irinotecan, and celecoxib in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:286–288. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181cda097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Small W, Jr, Berlin J, Freedman GM, et al. Full-dose gemcitabine with concurrent radiation therapy in patients with nonmetastatic pancreatic cancer: a multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:942–947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swets JA, Pickett RM. Evaluation of Diagnostic Systems: Methods From Signal Detection Theory. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, et al. Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2212–2217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–3952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stathopoulos GP, Syrigos K, Aravantinos G, et al. A multicenter phase III trial comparing irinotecan-gemcitabine (IG) with gemcitabine (G) monotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:587–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, et al. Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5513–5518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philip PA, Benedetti J, Corless CL, et al. Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus cetuximab versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Southwest Oncology Groupdirected intergroup trial S0205. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3605–3610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 80303) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3617–3622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]