Abstract

Background:

Negative symptoms and diminished cognitive ability are also considered as core features of schizophrenia. There are many studies in which negative symptoms and cognitive impairments are individually treated with atypical antipsychotic in comparison with either a placebo or a typical antipsychotic. There is paucity of studies comparing the efficacy of olanzapine and amisulpride on improvement of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments.

Aim:

To examine the effectiveness of amisulpride and olanzapine in treatment of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments in schizophrenia.

Materials and Methods:

Total 40 adult inpatients diagnosed as schizophrenia fulfilling inclusion/exclusion criteria were included in the study with their informed consent. These patients were recruited consecutively to one of the two drug regimen group, i.e. tab Amisulpride (100-300 mg/day) and tab Olanzapine (10-20 mg). Patients were evaluated on day 0 and day 60 with various rating scales like Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS), Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), and three different scales to measure drug side effects.

Results:

The mean SANS score in amisulpride and olanzapine group at day 0 and day 60 were 83.89 (±12.67) and 21.00 (±11.82) and 84.40 (±13.22) and 26.75 (±12.41), respectively. The mean rank of SCoRS global in amisulpride and olanzapine group at day 0 and day 60 were 4.78 (±1.13) and 2.78 (±0.63) and 4.85 (±1.18) and 3.30 (±1.12), respectively. The percentage improvement in SANS, SAPS, SCoRS interviewer, and SCoRS global in amisulpride group are 74.96%, 13.36%, 54.14%, and 42.00%, respectively. Similarly in olanzapine group percentage improvement in SANS, SAPS, SCoRS interviewer, and SCoRS global are 68.30%, 30.28%, 35.22%, and 31.95%, respectively. There is significant improvement in SANS, SCoRS, SAS, BPRS, and PANSS (Insight) in both amisulpride and olanzapine groups at the two time points. However, there is no significant difference between amisulpride and olanzapine group of patients.

Conclusion:

Both amisulpride and olanzapine group patients showed significant improvement in negative and cognitive symptoms from baseline to endpoint, but there was no significant difference between amisulpride and olanzapine group of patients.

Keywords: Negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, schizophrenia, olanzapine, amisulpride

Negative symptoms, which include blunted affect, alogia, asociality, avolition, and anhedonia in schizophrenia are deficiencies in vital areas of human endeavor, including motivation, verbal and nonverbal communication, experiencing pleasure, interest in socialization, and expression of affect, and it reflect reductions in aspects of higher cognitive, emotional, and psychological functioning. With treatment, negative symptoms decrease markedly with prevalence around 35-70% at the end of the follow-up. Due to the complex nature of negative symptoms, investigators must attempt to exclude patients with negative symptoms attributable to neuroleptic akinesia, depression, or an improvement in positive symptoms leading to decrease ratings of negative symptoms. Analysis of pooled data from clinical trials involving 62 medication-free schizophrenia patients treated with haloperidol or chlorpromazine for 8 weeks revealed that negative symptoms were reduced on average by 35%, compared to a mean 51.5% reduction of positive symptoms[1] though other studies reported contradictory findings.[2] In one of the path analysis, the superiority of olanzapine over risperidone has been shown and 52% of the effect was directly aimed at primary symptoms.[3] Olanzapine's efficacy against general negative symptoms has been demonstrated in many double-blind trials: Superior[4] or similar to risperidone;[5] and superior effect compared to haloperidol[6,7] or placebo.[8]

In a multi-center, double-blind comparison of two dosage levels of amisulpride (100 and 300 mg/day) with placebo over 6 weeks, the mean total SANS was reduced by 22.8% in the placebo group, 40.6% in the 100 mg/day group, and 45.9% in the 300 mg/day group, and differences between the placebo and amisulpride group were significant.[9] In 141 schizophrenia patients with predominantly negative symptoms (>60 on the SANS and <50 on the SAPS), amisulpride (100 mg/day) treatment resulted in a significantly higher proportion of responders than placebo (42 and 15.5%, respectively) on completion at 6 months.[10] A meta-analysis found a small but significant effect size compared with placebo (r = 0.26) despite significant superiority to placebo in the trials and a smaller, insignificant effect size compared with typical antipsychotics (r = 0.08) though this was possibly due to a lack of power.[11]

Cognitive functioning is moderately to severely impaired in patients with schizophrenia. It can lead to significant disabilities and can be considered to be an important treatment target. Cognitive deficits have been shown to lack correlation with severity of positive symptoms and to be only mildly correlated with severity of negative symptoms.[12]

A meta-analysis concluded that individuals with schizophrenia score between one-half to one-and-a-half standard deviations below the control mean in a wide variety of neuropsychological domains.[13] Some studies have documented mild improvements in cognition following the early acute phase[14], and the improvements have been associated with medication effects.[12] Amisulpride produces sustained improvement in neuropsychological performance[15] and reduced baseline score of cognitive symptoms from 19.8 to 11.2 on Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in schizophrenia patients.[16] Olanzapine was found to have a significant effect on some measures of reaction time, executive function, verbal learning and memory, and verbal fluency.[17] The improvement in the Stroop Color-Word Interference Test was approximately 45% of baseline, which is one of the larger effects of olanzapine on cognition reported for any of the atypical antipsychotic drugs.[18]

There are many studies in which negative symptoms and cognitive impairments are individually treated with atypical antipsychotic comparisons with placebo or comparisons with typical antipsychotic. This study assesses head on comparison with amisulpride and olanzapine in treatment of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments in schizophrenia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This hospital based open-label study was carried out at Ranchi Institute of Neuropsychiatry and Allied Sciences. The study protocol was submitted to and approved by the institutional ethical committee. The subjects were recruited for the study by consecutive sampling technique. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Patients were free to withdraw from the study at any time for any reason, without effect on their medical care.

Subjects

Total 40 adult inpatients diagnosed as schizophrenia as per ICD-10, DCR[19] fulfilling inclusion/exclusion criteria were taken up after obtaining informed consent. Inclusion criteria include patients between 18 and 60 years of both the sexes. Patients having a score of at least 60 on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)[20] and a score of less than 50 on the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)[21] were included.[10,22] They also had to comply with Andreasen's criteria[23] for negative schizophrenia, i.e. the presence of at least two of the following symptoms with severe intensity: Alogia, affective blunting, anhedonia, asociality, avolition/apathy, attentional impairment. Patient were drug naïve or drug free; drug free being defined as period of 4 weeks for all psychotropics and anti-parkinsonism drugs and depot neuroleptics for 8 weeks. Exclusion criteria include patients with any comorbid psychiatric condition including substance abuse or dependence (except tobacco and caffeine dependence), serious medical disorder, neurological condition as assessed by history, examination and laboratory investigations and pregnant women and nursing mothers.

Study procedure and assessment

Patients admitted for treatment were evaluated before start of any pharmacological intervention on very first day and other details were collected on a specially designed socio-demographic and clinical data sheet. Total 40 patients were recruited consecutively to one of the two dose regimen group, i.e. tab Amisulpride (100-300 mg/day), tab Olanzapine (10-20) mg. Starting dose of Amisulpride was 100 mg/day and Olanzapine was 10 mg/day. Antipsychotic medication was given once a day in the evening. Dose of antipsychotic medication was hiked 100 mg/week for Amisulpride (maximum up to 300 mg/day), 5 mg/week for Olanzapine (maximum up to 20 mg/day) depending on the patient response and tolerability until therapeutic dose was reached. Patients were evaluated on days 0 and 60. The evaluations included the following rating scales: SANS[20], SAPS[21], Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale (SCoRS)[24], Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)[25], Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS)[26] with evaluation of extrapyramidal Symptoms by Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (SAS)[27], tardive dyskinesia by Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS)[28] and akathisia by Barnes Akathisia Rating scale (BAS)[29] and (PANSS)[30] insight item. Inj. promethazine up to 50 mg/day was prescribed in case of insomnia or agitation for initial few days of admission. For insomnia, akathisia or anxiety, lorazepam (0.5-4 mg/day) was prescribed for minimum duration. For extrapyramidal side effects, Tab. Trihexyphenidyl was given up to 4 mg/day for minimum duration. Detailed physical examination, routine hematological investigation and mental status examination (MSE) were done.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed with the help of appropriate parametric (independent sample t-test) for continuous variables like age, age of onset of psychosis, duration of untreated psychosis, etc., For other socio-demographic variables and clinical variables assessed as category variables, Chi-square test was applied. Non-parametric test like Mann-Whitney was used to compare the scores on scales of SANS, SAPS, SCoRS, etc., for two different groups. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to see the significant differences between subject's scores before and after antipsychotic treatment on various scales in the same group of patients. Mixed ANOVA was used to compare the various clinical data and laboratory parameters between two groups. The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences-Version 16.0 (SPSS 16.0). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.001.

RESULTS

Patients

Baseline demographic variables like age, sex, etc., did not differ between the two treatment arms. Mean age in years in amisulpride and olanzapine groups were 28.35 ± 6.76 and 30.60 ± 5.59, respectively. Age of onsets in years was comparable between amisulpride and olanzapine groups (23.75 ± 5.36, 24.20 ± 4.85), but duration of illness and duration of untreated psychosis in months were more in olanzapine group than in amisulpride group (73.20 ± 44.37 > 49.60 ± 33.38; 51.40 ± 34.65 > 36.30 ± 31.74). Male patients predominates in both groups. The marital status in 50% patients was single. In all, 45% of the patients were laborer by occupation, and 65% patients belong to low socio-economic status. There were no inter-group differences in clinical characteristics at baseline. Stress before the onsets of symptoms was present in 92% of the patients. Most of the patients had acute onset (77%), continuous course (72%), and all patients had deteriorating progress. There were no past history (70%) and family history of psychiatric illness (57%) in majority of the patients, and 72% had adequate social support. The mean dose of Amisulpride and Olanzapine were 222 ± 41.0 and 16 ± 3.47. The starting dose was 100 mg for amisulpride and 10 mg for olanzapine. At the end point, 50% of patients in amisulpride group were being treated with 200 mg, 40% with 100 mg and 10% required 300 mg. In olanzapine group, 50% of the patients end up with 15 mg, 35% with 20 mg and 15% with 10 mg. The full 60 days of treatment was completed by 39 patients (97.5%). One patient was dropped from amisulpride group after 8 days of treatment due to severe hypotension on 200 mg of amisulpride.

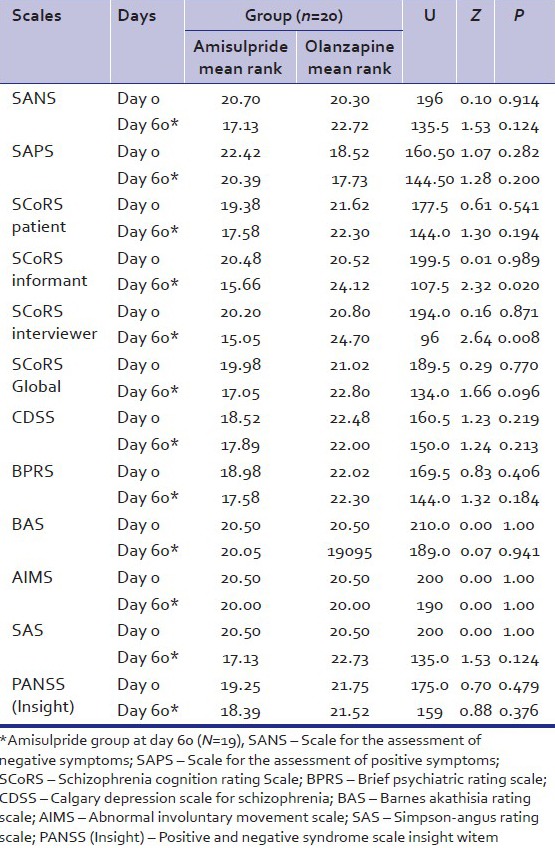

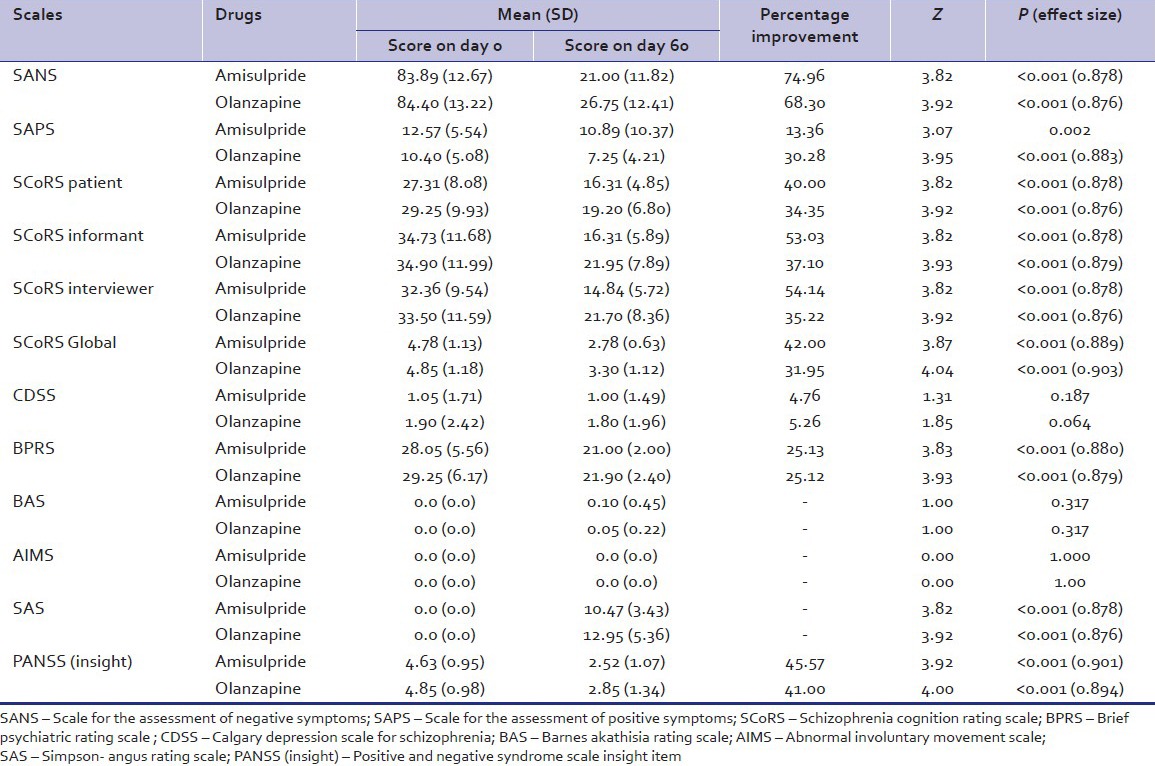

Table 1 shows the various scales rating at 0th day and at 60th day in both the groups. There was no significant difference between two groups on scores on various scales. Table 2 shows scores obtained by amisulpride group and olanzapine group on various rating scales at day 0 and day 60 and the percentage improvement in various scales in both the groups. There are significant differences in the scores of SANS, SCoRS patient, SCoRS informant, SCoRS interviewer, SCoRS Global, BPRS, SAS, and PANSS (Insight).

Table 1.

Comparison of the various scales rating at day 0 and day 60 between Amisulpride and Olanzapine groups

Table 2.

Comparison of scores obtained by amisulpride group and olanzapine group on various rating scales at day 0 and day 60

Efficacy analysis

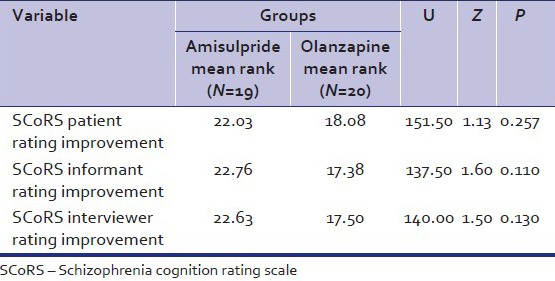

The mean SANS score of amisulpride and olanzapine group at baseline were comparable. Significant improvement was documented for each of the group and at the end of the 60 days. The percentage improvement in negative symptoms was 74.9% and 68.3% in amisulpride and olanzapine group with effect size of 0.878 and 0.876, respectively. The improvement in SAPS score at the end of the study was 13.36% and 30.28% in amisulpride and olanzapine group. The improvement was significant in olanzapine group with effect size of 0.883. Similarly, there was significant improvement in SCoRS scale in SCoRS patient, SCoRS informant, SCoRS interviewer, and SCoRS global score with large effect size. The SCoRS global percentage improvement was 42 and 31.95 in amisulpride and olanzapine group, respectively, which was statistically significant in each group. A slight greater improvement in SCoRS improvement items (patients, informant, and interviewer) was observed in amisulpride group as compared with olanzapine group, but no statistical differences were found among groups [Table 3]. Over the study duration, the total BPRS score fell by 7.05 ± 3.56 points in the amisulpride group and by 7.35 ± 3.77 points in the olanzapine group. BPRS factor scores representing negative symptoms improved more over the duration of the study and to a similar extent in both treatment groups, the percentage improvement overall being 25.13 and 25.12, respectively, (P < 0.001). In PANSS Insight item due to improvement of psychotic symptoms, there was improvement in the recognition of insight (45.57% in amisulpride group, 41% in olanzapine group) [Table 2].

Table 3.

Comparison of the SCORS rating improvement of patients in amisulpride and olanzapine groups

Safety analysis

Extrapyramidal neurological symptoms were quantified using the Simpson–Angus Scale, the Barnes Akathisia Scale, and the AIMS. There were statistical differences in SAS mean score in amisulpride and olanzapine group at the endpoint, the baseline score was zero at inclusion (10.47 ± 3.43 and 12.95 ± 5.36, respectively, P < 0.001). AIMS instruments did not showed any symptom deterioration over the course of the study in either treatment group.

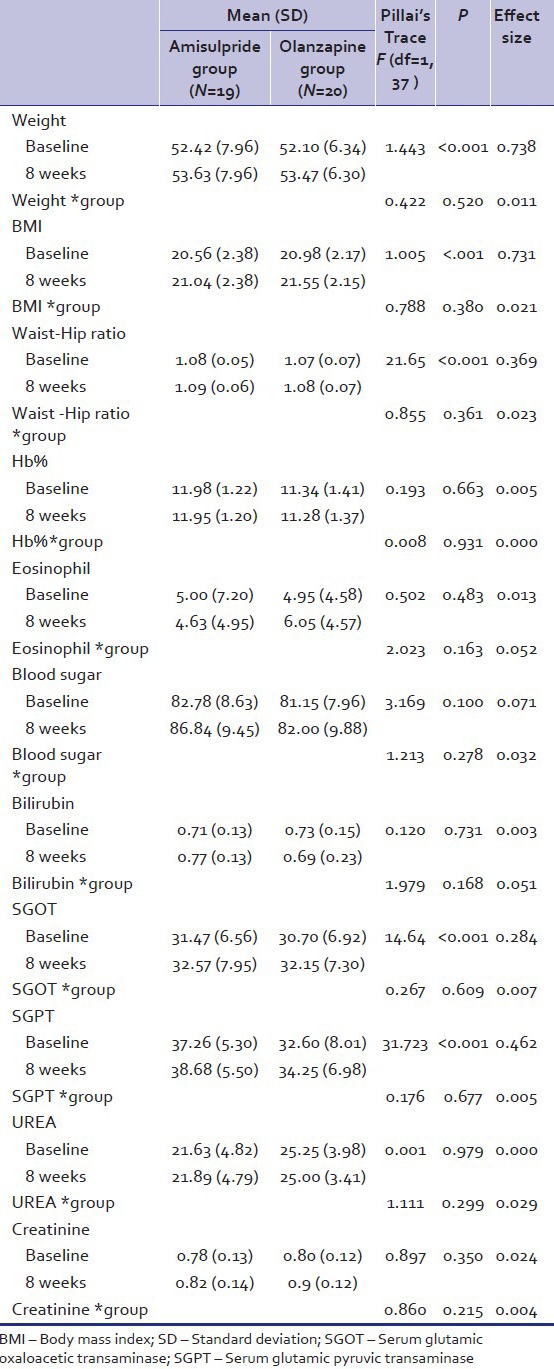

Treatment-emergent adverse events appeared during the course of the study with a similar frequency in the two treatment groups. Body weight and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) at inclusion were similar for the two treatment groups [Table 4]. Overall, two patients (5%) had a BMI of 25 or higher. There was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) in mean weight change from baseline to endpoint between treatment groups, olanzapine-treated patients experiencing greater weight gain (1.37 ± 0.04 kg) than those receiving amisulpride (1.21 ± 0 kg) (effect size = 0.738). Similarly, there was a significant mean increase (amisulpride - 0.48 ± 0; olanzapine – 0.57 ± 0.02; effect size = 0.731) in BMI and in waist-hip ratio (amisulpride – 0.01 ± 0.01; olanzapine – 0.01 ± 0; effect size = 0.369) in both groups. Mild elevated mean liver transaminase levels (i.e. serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase [SGPT], serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase [SGOT]) were reported in both group (P < 0.001) with effect size of 0.462 and 0.284, respectively. There was no other significant finding with regard to physical and laboratory finding [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of the various clinical data and laboratory parameter at day 0 and days 60 in Amisulpride and olanzapine group

DISCUSSION

This open-label study compared the effectiveness of amisulpride and olanzapine in treatment of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments in schizophrenia.

Methodological issues

Schizophrenia patients with predominantly negative symptoms were included. Patients having >60 points on SANS scale were included, and they fulfilled Andreasen criteria for negative schizophrenia, i.e. the presence of at least two of the following symptoms with severe/marked intensity: Alogia, affective blunting, anhedonia, asociality, avolition/apathy, attentional impairment.[10] A score of <50 points on SAPS scale was kept so that positive symptoms would be not at forefront.[22] The working group consensus[31] defined a score of mild or less (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale item scores of ≤3; BPRS item scores of ≤3, using the 1-7 range for each item; SAPS and SANS item scores of ≤2) simultaneously on all items as representative of an impairment level consistent with symptomatic remission of illness. Lieberman et al. had proposed “full remission” when there are no residual positive symptoms and scores of ≤2 (mild) on all SANS negative symptom global items.[32] It justifies the cut-off values of SANS and SAPS scale whose items are 25 and 34, respectively. The duration of the treatment varied from 6 weeks to 26 weeks in various studies.[9,10,22] In this study, duration of 8 weeks was kept, which is sufficient for proper assessment.

Amisulpride at low doses shows selective blockade of presynaptic dopamine autoreceptors and increased release of dopamine. It displays selectivity for limbic rather than striatal structure. It has been shown that substantial negative symptoms can be effectively treated with amisulpride doses of 50-300 mg.[9,10,21,32] Olanzapine blocks serotonin 2A and 5HT2C receptors, causing enhancement of dopamine release in brain regions and thus reducing the negative symptoms and improves cognitive and affective symptoms. For the majority of the patients, 7.5-10 mg of olanzapine has been established as lower bound of minimally effective dose range based on clinical data. In an earlier study, a dose range of 5-30 mg of olanzapine was used and mean dose was actually somewhat higher among deficit patients as compared with non-deficit patients,[33] whereas another study used 12.5-17.5 mg/day of olanzapine and that produced a significantly greater improvement in the SANS rating.[34] The dosing schedule was once daily evening administration of antipsychotic taking into consideration the sedating property of the drugs. So, in this study, dose range of 100-300 mg of amisulpride and 10-20 mg of olanzapine was used depending on the patient response and tolerability.

This study is designed with the primary objective to show efficacy of amisulpride and olanzapine on negative symptoms. In our sample, the patients had low levels of positive and depressive symptoms, and no EPS at baseline as assessed by SAPS, CDSS, and SAS, respectively. AIMS and BAS were also applied to assess side effects of both drugs. Necessary medications were prescribed for minimum duration, so that the side effects should stay relatively stable or ameliorate during the study and would not interfere with the assessment of negative symptoms.

The SCoRS is an interview-based assessment that covers almost all the cognitive domains tested in the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery. The administrator's global rating was shown to be the single SCoRS measure that correlated most significantly with measures of cognition (Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia), performance-based assessment of function (UPSA), and real-world assessment of function (Independent Living Skills Inventory). It has high face validity. All these advantages prompted us to use it in our study.

The CDSS was more specific and valid for the assessment of depression in patients with schizophrenia than other general scales measuring depression (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression) or Depression related sub-scores of general scales for schizophrenia (PANSS-D). The CDSS is able to distinguish depression from the negative psychotic symptoms and EPS.[35]

Overall, the strength of our study compared with previous studies are its prospective, comparative design using two groups in patients with schizophrenia with negative and cognitive impairment and consistent results between objective assessment and subjective measures.

Subject characteristics

Total 40 patients were included and exposed to treatment. There were no significant differences among treatment groups regarding baseline characteristics (sex, religion, marital status, education, community, occupation, habitat, and economic status, etc.), and it is similar to the previous studies.[10,22,36] Male subjects were predominant in our sample 37 (93%) as compared with females 3 (7%). In earlier studies also, female representation was less than male due to various reasons.[9,22] In our study, age of onset of schizophrenia was 23.75 ± 5.36 years and 24.20 ± 4.85 years in amisulpride and olanzapine group, respectively, which is comparable to that of earlier studies.[33,37]

Mean duration of illness in our sample (49.60 ± 33.38 and 73.20 ± 44.37 months in amisulpride and olanzapine group) was somewhat less as compared with earlier studies. Mean duration of illness in months in studies using Amisulpride to treat negative symptoms were 121.2 ± 61.2[22], 116.4 ± 100.8[10], 96 ± 85.[9] The mean duration of illness in months in studies where olanzapine was used to treat negative symptoms was 133[36] and 152.4 ± 72.0[34], whereas for cognition, it was 11.0 ± 12.9[38] and 220.8 ± 103.2.[37]

Effect of drugs

Negative symptoms

Both amisulpride and olanzapine group patients showed a significantly greater improvement in mean total SANS score from baseline to endpoint. There was no statistically significant difference between the two drug groups. The baseline scores on both the SAPS and the CDSS were low, and the changes in these scores were also low. Furthermore, assessment of extrapyramidal symptoms according to the SAS, BAS, and AIMS scores showed that these symptoms were absent at baseline and at endpoint did not differ significantly between groups. These findings suggest that the improvement in negative symptoms was not due to a substantial concomitant improvement in positive symptoms, depressive symptoms, or the result of changes in extrapyramidal symptoms. The clinical improvement observed with amisulpride and olanzapine treatment in this study is consistent with the results of placebo-controlled studies of low-dose amisulpride (mostly 100-300 mg/day) and olanzapine (10-20 mg/day) in schizophrenia patients with predominantly negative symptoms.[6,9,10,34]

Cognitive impairment

Amisulpride and olanzapine produced modest but significant improvements in neurocognition assessed by SCoRS. There were no significant differences between treatments group in overall cognitive scores and also in SCoRS rating improvement. The improvement in cognitive function produced by the atypical antipsychotic drugs in our study is independent of the improvement in psychopathology because there is evidence that cognitive measures correlate poorly with psychopathology, especially positive symptoms and negative symptoms.[39] Cognitive change also was not clearly related in our study to a range of other possible mediating factors, including extrapyramidal symptoms or adjunctive medication use, which did not differ among treatment groups and this is in line with an earlier study.[40] Mean dose of amisulpride and olanzapine were 222 ± 41.0 and 16 ± 3.47. Due to comparative low dose, side effects were low, and, in particular, less anticholinergic side effects were encountered that were known to affect memory and other cognitive function. Patients, who are antipsychotic-naïve or drug free for considerable period of time when beginning treatment, have been shown to obtain particularly large benefits from treatment with atypical antipsychotics.[41] This also occurred in our case due to the strict selection of the patients. Most of the cognitive benefit of atypical antipsychotics occurs in the first few months of treatment.[38] Various explanations proposed for the improvement in cognitive functions include an increase in muscarinic cholinergic, 5-HT2A/2C serotonergic, and alpha2A adrenergic activity or enhancing D1 dopamine receptors below their “therapeutic window.”

Overall, in our study, patient improvement in terms of symptom resolution was greater than other studies.[9,10,38] This could be due to various factors. Duration of illness in our study was half to one-third as compared with other studies. Moreover, in our patient group, presence of stressor, acute mode of onset, nil family history of psychiatric illness in majority, good family support system, and less first degree relative in family psychiatric history act favorably in improving the symptoms. Less degree of chronicity and no treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients in samples had also contributed to better response.

Safety

In previous studies, adverse effect that causes patient discontinuation from treatment ranged from 3.2% to 18.2%[9,10,22], and in our study, it was 5%. In previous studies, discontinuation was mainly due to lack of efficacy on negative symptoms due to chronic illness. The most common adverse effect in previous studies was sleep disorder, weight gain, anxiety, nervousness, and amenorrhea. Though hypotension is a documented side effect of amisulpride, caution should be exercised in prescribing initial dose and “start low and go slow” dictum must be followed. There was a little difference in mean weight change from baseline to endpoint between treatment groups, olanzapine-treated patients experiencing slightly greater weight gain than those receiving amisulpride (percentage change amisulpride vs. olanzapine 2.30% and 2.62%) in just 8 weeks’ clinical study. There were minor changes in BMI and waist-hip ratio, more in olanzapine group than in amisulpride group. In terms of cardiovascular safety, neither amisulpride nor olanzapine had any effect on heart rate or arterial blood pressure. These findings are in line with the study of Mortimer et al.[42] The difference between the two drugs can possibly be explained by the antagonist activity of olanzapine at 5-HT2 receptors, for which amisulpride has no affinity. There were minimal changes in liver transaminase levels (i.e., SGPT, SGOT), which reached statistical significant in both groups in 8 weeks of treatment underlining the need for caution, and monitoring should be done.

Limitations of the study include possible selection bias being a tertiary care hospital-based study where patients with more severe illness are more likely to be included. The sample size was modest. The study was not double blind as well as not placebo controlled and probability of rater bias could not be refuted due to open-label study.

In conclusion, treatment with amisulpride and olanzapine resulted in significant improvement in negative symptoms and cognitive impairments in schizophrenia patients, but there was no significant difference between amisulpride and olanzapine group of patients. Both treatments were associated with a comparable low incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breier A, Wolkowitz OM, Doran AR, Roy A, Boronow J, Hommer DW, et al. Neuroleptic responsivity of negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1549–55. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.12.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartung B, Wada M, Laux G, Leucht S. Perphenazine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD003443. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003443.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez E, Ciudad A, Olivares JM, Bousoño M, Gómez JC. A randomized, 1-year follow-up study of olanzapine and risperidone in the treatment of negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:238–49. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000222513.63767.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran PV, Hamilton SH, Kuntz AJ, Potvin JH, Andersen SW, Beasley C, Jr, et al. Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:407–18. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199710000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conley RR, Mahmoud R. A randomized double-blind study of risperidone and olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:765–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breier A, Hamilton SH. Comparative efficacy of olanzapine and haloperidol for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:403–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton SH, Revicki DA, Genduso LA, Beasley CM., Jr Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: Quality of life and efficacy results of the North American double-blind trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:41–9. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beasley CM, Jr, Sanger T, Satterlee W, Tollefson G, Tran P, Hamilton S. Olanzapine versus placebo: Results of a double-blind, fixed-dose olanzapine trial. Psychopharmacology. 1996;124:159–67. doi: 10.1007/BF02245617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer P, Lecrubier Y, Puech AJ, Dewailly J, Aubin F. Treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia with amisulpride. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:68–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loo H, Poirier-Littre MF, Theron M, Rein W, Fleurot O. Amisulpride versus placebo in the medium-term treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:18–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Engel RR, Kissling W. Amisulpride, an unusual “atypical” antipsychotic: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:180–90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keefe RS, Bilder RM, Harvey PD, Davis SM, Palmer BW, Gold JM, et al. Baseline neurocognitive deficits in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2033–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: A quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–45. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simonsen E, Friis S, Haahr U, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Melle I, et al. Clinical epidemiologic first-episode psychosis: 1-year outcome and predictors. Acta Psychiatrica Scand. 2007;116:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortimer AM, Joyce E, Balasubramaniam K, Choudhary PC, Saleem PT. SOLIANOL Study Group. Treatment with amisulpride and olanzapine improve neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:445–54. doi: 10.1002/hup.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrera-Estrella M, Apiquian R, Fresan A, Sanchez-Torres I. The effects of amisulpride on five dimensions of psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia: A prospective open- label study Miguel. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green MF, Marshall BD, Jr, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marder SR, McGurk S, et al. Does risperidone improve verbal working memory in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:799–804. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meltzer HY, McGurk SR. The effects of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine oncognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 1999;25:233–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreasen NC. Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andreasen NC. Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1984. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danion JM, Rein W, Fleurot O. Improvement of schizophrenic patients with primary negative symptoms treated with amisulpride. Amisulpride Study Group. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:610–16. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andreasen NC, Olsen S. Negative versus positive schizophrenia: Definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:789–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keefe RS, Poe M, Walker TM, et al. The Schizophrenia Cognition Rating Scale: An interview based assessment and its relationship to cognition, real world functioning, and functional capacity. Am J Psychiatry. 2006b;163:426–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3:247–51. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(90)90005-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munetz M, Benjamin S. How to examine patients using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:1172–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.11.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes TR. Arating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Jr, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in schizophrenia: Proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:441–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Szymanski S, Johns C, Howard A, et al. Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: Response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1744–52. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, Tripodis K, Gonzalez V, Mintz J. Differential efficacy of olanzapine for deficit and nondeficit negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:987–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beasley CM, Jr, Tollefson G, Tran P, Satterlee W, Sanger T, Hamilton S. Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: Acute phase results of the North American double-blind olanzapine trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:111–23. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00069-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim SW, Kim SJ, Yoon BH, Kim JM, Shin IS, Hwang MY, et al. Diagnostic validity of assessment scale for depression in patients of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lecrubier Y, Quintin M, Bouhassira E. The treatment of negative symptoms and deficit states of chronic schizophrenia: Olanzapine compared to amisulpride and placebo in a 6-month double-blind controlled clinical trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:319–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Volavka J, Czobor P, Hoptman M, Sheitman B, et al. Neurocognitive effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in patients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1018–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keefe RS, Sweeney JA, Guy H, Hamer RM, Perkins DO, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of the effects of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone on neurocognitive function in first-episode psychosis. A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1061–71. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagger C, Buckley P, Kenny JT, Friedman L, Ubogy D, Meltzer HY. Improvement in cognitive function and psychiatric symptoms in treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients receiving clozapine. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34:702–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90043-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:255–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keefe RS, Seidman LJ, Christensen BK, Hamer RM, Sharma T, Sitskoorn MM, et al. HGDH Research Group. Long-term neurocognitive effects of olanzapine or low-dose haloperidol in first-episode psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mortimer A, Martin S, Lôo H, Peuskens J. SOLIANOL Sudy Group. A double-blind, randomized comparative trial of amisulpride versus olanzapine for 6 months in the treatment of schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:63–9. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]