Abstract

Background:

The etiology of alcohol dependence is a complex interplay of biopsychosocial factors. The genes for alcohol-metabolizing enzymes: Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH2 and ADH3) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) exhibit functional polymorphisms. Vulnerability of alcohol dependence may also be in part due to heritable personality traits.

Aim:

To determine whether any association exists between polymorphisms of ADH2, ADH3 and ALDH2 and alcohol dependence syndrome in a group of Asian Indians. In addition, the personality of these patients was assessed to identify traits predisposing to alcoholism.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, 100 consecutive males with alcohol dependence syndrome attending the psychiatric outpatient department of a tertiary care service hospital and an equal number of matched healthy controls were included with their consent. Blood samples of all the study cases and controls were collected and genotyped for the ADH2, ADH3 and ALDH2 loci. Personality was evaluated using the neuroticism, extraversion, openness (NEO) personality inventory and sensation seeking scale.

Results:

Allele frequencies of ADH2*2 (0.50), ADH3*1 (0.67) and ALSH2*2 (0.09) were significantly low in the alcohol dependent subjects. Personality traits of NEO personality inventory and sensation seeking were significantly higher when compared to controls.

Conclusions:

The functional polymorphisms of genes coding for alcohol metabolizing enzymes and personality traits of NEO and sensation seeking may affect the propensity to develop dependence.

Keywords: Alcohol dependence, alcohol metabolism, genotype profiles, personality

Alcohol has played a central role in almost all human cultures since prehistoric times. The extent of worldwide alcohol use is estimated to be 2 billion. The harmful use of alcohol results in 2.5 million deaths each year. Alcohol is the world's third largest risk factor for disease burden. According to the global burden of disease analysis, alcohol is responsible for 5.5% of the Disability adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide.[1] Despite much research, surprisingly little is known about the cause of alcoholism. Problem drinking is thought to result from a variety of interacting biopsychological phenomenon.[2] The genetic model of alcohol dependence has received a renewed interest in recent times because of genetic epidemiological work. The result from three main types of population-based studies, such as - family, twin, and adoption studies have led researchers to believe that alcoholism has a genetic component.[3] If there is genetic component that is susceptibility to alcoholism, what is its mechanism? The answer can be sought at two levels: Alcohol metabolism and alcohol action on the brain. Twin studies have shown a strong genetic influence on alcohol metabolism and variability in activity of enzymes involved in metabolizing alcohol i.e. alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrongenase (ALDH).[4,5]

Alcohol dehydrogenase is determined by three autosomal gene loci (ADH1, ADH2, ADH3). Only ADH2 is active during adult life. In 5-20% individual Europeans and in 90% of Japanese, an atypical variant is discovered. At physiological pH, the atypical enzyme shows much more activity than the more common one. It has been suggested that alcohol oxidation proceeds more rapidly in carriers of the atypical enzyme. Atypical variant of ALDH is also found in the Japanese population with the frequency of 50% while it is rare in Europeans; it is associated with decreased ALDH activity. The presence of these variants of atypical enzymes results in the increase of acetaldehyde levels in the body. The increase in acetaldehyde levels is associated with redness of face and skin, burning sensation and general discomfort, collectively termed as the “flushing phenomenon”. The presence of any one or both of these atypical variants in a person may influence alcohol dependence (AD) vulnerability.[6,7,8,9]

Personality variables also seem to affect the initiation into alcohol use. Conversely, alcohol use may also affect personality. Prolonged drinking, even if initiated to relieve guilt and anxiety, often produces anxiety and depressive tone to temperament. These varied changes in personality attributes, may in turn, explain the continuation or cessation of alcohol use.[10] Using the five factor model it has been shown that alcohol abuse and dependence is associated with high levels of neuroticism and excitement seeking and low levels of conscientiousness and agreeableness.[11,12] Researchers have found that the personality characteristics are also heritable.[13]

There is paucity of Indian work in this field. The present study attempts to address this complex and intriguing issue and is an effort to study the genotype profiles of enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism (ADH, ALDH) and personality traits, which affect vulnerability to alcohol dependence syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

A total of 100 consecutive male inpatients of tertiary care service hospital fulfilling the ICD-10 (DCR)[14] diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence syndrome were taken for study. Cases of co-morbid psychiatric disorders and polydrug abuse were excluded.

Controls

An equal number of controls matched for age, sex and ethnicity and not suffering from alcohol dependence syndrome or physical/psychiatric illness were drawn from attendants of patients.

Informed consent of all cases and controls was taken. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from institutional ethical committee.

Tools

Sociodemographic proforma

A proforma was prepared to elicit a detailed history including family history of alcoholism in first-degree relatives, sociodemographic variables, clinical and mental state examination and subjective response to alcohol.

The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R)

The NEO-PI-R[15] consists of 240 items answered on a five-point Likert format ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. The NEO-PI-R assesses personality on five domains of neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness. The internal consistency information of the NEO presented in the manual was derived from the full job performance sample (n = 1539). The internal consistency of the NEO-PI-R was high at: N = 0.92, E = 0.89, O = 0.87, A = 0.86, C = 0.90.[16] The test-retest reliability reported in the manual of the NEO PI-R over 6 years was: N = 0.83, E = 0.82, O = 0.83, A = 0.63, C = 0.79. Costa and McCrae point out that this not only shows good reliability of the domains, but are also stable over a long period of time (past the age of 30), as the scores measured six years apart vary only marginally more than the scores as measured a few months apart.[15] Exploratory factor analysis that have used varimax rotation of principal components in younger and older, white and nonwhite, and male and female subsamples have shown very similar five-factor structures that have supported the theoretical model.[17] The NEO-PI-R has been translated into several languages and used in more than 50 cultures.[18] A large literature demonstrates cross-observer agreement and prediction of external criteria such as psychological well-being, health risk behaviors, educational and occupational achievements, coping mechanisms, and longevity.[15,19]

CAGE questionnaire

The CAGE is a four-item screening questionnaire designed to identify and assess potential alcohol abuse and dependence. Each letter reflects the core concept of each of the items. The CAGE is extremely short and easily administered taking less than a minute to complete. The items from the CAGE have good internal reliability with all four items correlating with each other indicating that the CAGE is measuring a single homogenous construct. The CAGE performed well at detecting current at-risk drinking (defined as 8 or more standard drinks a day) with a sensitivity of 84%, specificity of 95% and positive predictive value of 45% using a cutoff point of 2 or more affirmative responses.[20]

Indian adaptation of sensation seeking scale

The original sensation seeking scale (SSS), form V[21] is well standardized and is widely used. It is a 40-item, forced choice inventory where each represents a tendency towards sensation seeking propensity and has two statements (marked A and B) indicating higher (scored as one) or lower (scored as zero) sensation seeking. Based on the responses, a total score is constructed that may range from 0 through 40. Greater the score, higher is the sensation seeking. Along with this total sensation seeking score, the SSS also yields scores for its four sub scales. Each subscale has 10 items in it. These subscales are as follows: Thrill and Adventure Seeking, Experience Seeking, Boredom susceptibility, and Disinhibition. As per the Indian adaptation modifications of the original scale, took either of the two forms: In some questions the language was made more comprehensible, translating colloquial American English into simple English while with items that were alien to the Indian socio-cultural background, the original items were replaced with new items tapping the same dimension but whose content reflected the prevailing socio-cultural mores. The scale was standardized on an Indian population. For the present study, the Indian adaptation of the SSS which has adequate test-retest reliability, internal consistency and discriminant validity was used.[22]

Genotyping (ADH2, ADH3 and ALDH2 genes)

DNA extraction

Blood of 2 ml from venous was drawn from each patient and controls. DNA extraction was done by the CTAB DTAB protocol.

Amplification of ADH2/ADH3 genes

Portions of exons 3 and 9 of the ADH2 gene and of exon 8 of the ADH3 gene were amplified by a minor modification of the PCR methods described by Yiling et al.,[23] which allowed amplifications of all three exons in a single reaction, ADH alleles were distinguished by using allele-specific oligonucleotides as probes to hybridise amplified DNA fixed to nitrocellulose.

Amplification of ALDH2 gene

Exon 12 of the ALDH2 gene was amplified by using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[24] Allele specific oligonucleotide probes also distinguished ALDH alleles.

PCR protocol

Thirty cycles of denaturation at 93°C, annealing at 50°C and extension at 72°C were carried out in a Biorad cycler. The reaction was carried out using a kit from Bangalore Genie using conditions specified by the manufacturer. The amplified products were dot blotted on a nitrocellulose membrane.

Procedure

After the patients were detoxified and stabilised mentally and physically, the CAGE, SSS and NEO-PI-R were individually administered to each of the cases and controls. All patients underwent routine investigations including LFT, and ultrasonography (USG) abdomen. Blood sample was also sent for genotyping. The scoring was done using the scoring key given with the test kits. Raw scores were converted to test scores and analysed as per the test manual.

Statistical analysis

The data was analysed using non-parametric statistics. Chi square test was used for comparison frequency data like socio-demographic details, genotype frequency and allelic frequency. Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of ordinal data like total and subscale scores on the SSS and domain scores of the NEO-PI-R.

RESULTS

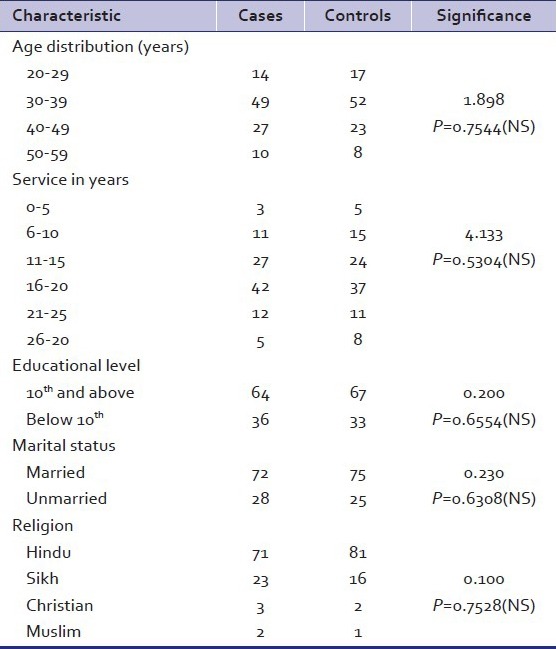

The demographic characteristics of alcoholics and controls are shown in Table 1. They did not differ significantly on age, years of service, educational level, marital status, and religion. However, alcoholics had a significantly higher family history of alcoholism and significantly higher percentage of punishments (N = 46) as compared to controls (N = 13). Majority of cases (63%) had history of drinking for ten years or more and, on admission, 67% of the patients had withdrawal features with 26% having complicated withdrawal in the form of seizures and delirium tremens. Results of investigations in cases of alcohol dependence revealed that 77% had evidence of physical problems due to alcohol in the form of hepatomegaly and more than half of the cases (56%) had elevated serum transaminases. Fatty changes in liver on USG abdomen were seen in 18% of cases. On administration of the CAGE questionnaire, twenty-six patients scored 1 and seventy-four scored 2 or more. The score of all controls was 0. The sensitivity and specificity of the CAGE was 76% and 100%, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of alcohol dependent patients (n=100) and matched control subjects (n=100)

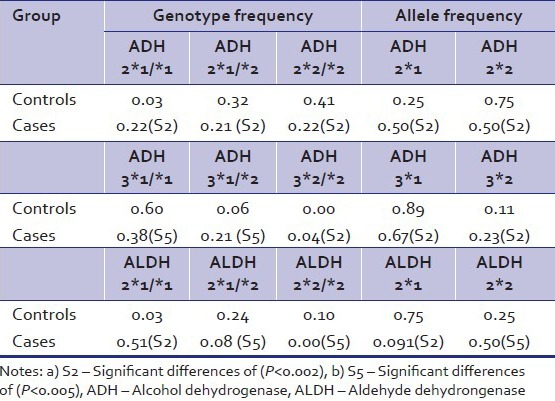

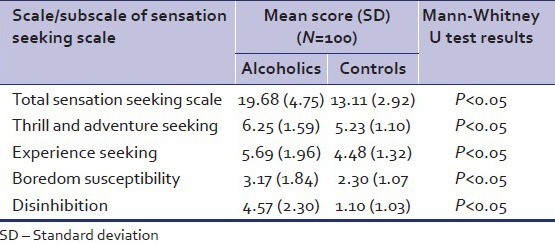

As shown in Table 2, cases of alcohol dependence had significantly lower allele frequencies of both ADH2*2 and ADH3*1 when compared with controls. The genotype frequencies of ADH2*1/*1, ADH2*1/*2, and ADH2*/*2 in cases were (0.22, 0.21 and 0.22, respectively). Among alcoholics homozygous for ADH3*1 the genotype frequency was 0.38 as compared to controls (0.60). The allele frequencies of ALDH2*2 were significantly lower in cases (0.09) as compared to controls (0.25). The genotype frequencies of those homozygous for ALDH2*1 in cases and controls were 0.51 and 0.33, respectively and those homozygous for ALDH2*2 were 0.00 and 0.10. On the SSS the mean (SD) of total sensation seeking scores (TSS) for cases were 19.68 (4.75) as compared to 13.11 (2.92) in controls [Table 3].

Table 2.

Genotype frequency and allelic frequencies in cases (N=100) and controls (N=100)

Table 3.

Distribution of scores on sensation seeking scale in alcoholics and controls

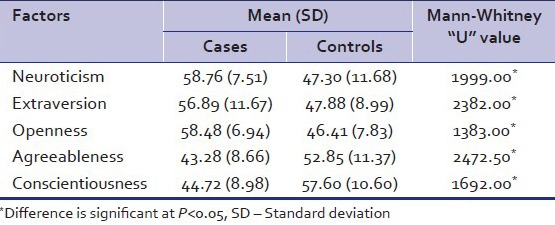

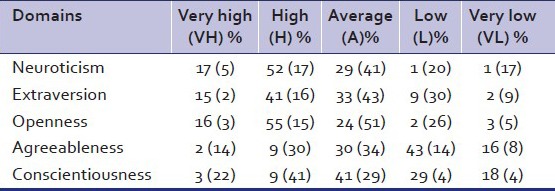

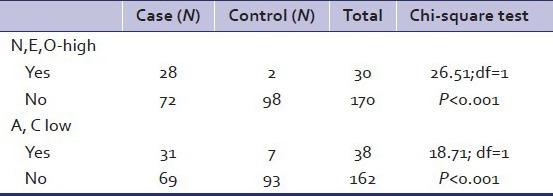

Analysis of NEO-PI-R scores revealed that the mean scores of Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Openness were significantly higher in cases as compared to controls. The mean scores of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness were significantly lower in cases as compared to controls [Table 4]. Table 5 depicts the percentage scores of cases and controls in the different domains. Further analysis of the data was done by taking the domain scores of Neuroticism, Extraversion and openness together. Table 6 shows that a significant number of cases (N = 28) had high to very high values on the cluster of Neuroticism, Extraversion, and openness. Similar analysis was done by taking the domain scores of Agreeableness and Conscientious together. Table 6 depicts that a significant number of cases (N = 31) had low values on domain of Agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Table 4.

NEO PI domain scores of cases and controls

Table 5.

NEO PI - percentage scores of cases (controls) in different domains

Table 6.

Cluster of cases/controls with high to very high values on N, E, and O and cluster of Cases/Controls with low to very low values on A and C domains

DISCUSSION

In the present study, majority of alcoholics were less than 40 years of age (N = 63). More than 15 years of service was noted amongst 59% of alcoholics. Alcoholics were noted to have more punishments (N = 46) as compared to controls (N = 13). This has been observed by earlier studies.[25] The punishments may also be indicators of an underlying alcohol problem in a soldier. A substantial proportion of cases (N = 37) were found to have positive family history. Similar findings have been reported in earlier Indian studies[25] and the study findings imply heritability of alcohol dependence, as we know from recent research. Majority of the alcoholics gave a history of drinking regularly for 10 years or more (N = 63) before coming to medical/psychiatric attention, which is in agreement with earlier studies.[25,26,27]

More than two-thirds (67%) of cases were noted to be in alcohol withdrawal at the time of admission. A significant proportion of cases (26%) had complicated withdrawal in the form of seizures and delirium tremens. These figures were somewhat higher than seen in few previous studies.[25,26] Various investigations showed the alcoholics having physical problems due to alcohol in the form of hepatomegaly (77%), fatty liver (18%) and elevated serum enzymes (56%), which is similar to findings of earlier studies.[25,26,27]

The CAGE is a very brief, relatively non-confrontational questionnaire for detection of alcoholism. CAGE test scores of >2 has a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 100% for the identification of problem drinkers.[20] Thus the CAGE is of limited utility as a screening test for alcohol dependence in the security forces. This finding is in agreement with an earlier study on Indian security forces.[28]

Asians have been found to have a predominance of ADH2*2 and ADH3*1 alleles[29] and about 90% of Orientals are typical for the ADH2 locus, either heterozygous (ADH2*1/*2) or homozygous (ADH2*2/*2) and their live ADH activity is usually higher.[30,25] The present study is the first report of a significant difference in ADH2 and ADH3 genotypes between alcoholics and nonalcoholics of Asian Indians. Until now, the deficiency of mitochondrial ALDH2 was the only defined genetic factor known to affect the risk of developing alcoholism.[31,32]

Alcoholics have significantly lower frequencies from the same population.[33,34] This difference is dependent of the ALDH2 genotype as demonstrated by comparison of the groups homozygous for the ALDH2*1 allele. This indicated that the ADH2 and ADH3 alleles the propensity for alcoholism. ADH2 and ADH3 are closely linked on chromosome 4. Among the alcoholics, homozygous for ADH2*2, the ADH3*1 allele frequently is not significantly different than that among total population for non-alcoholics.

It is well documented that allele frequencies of ALDH2*2 are significantly decreased in alcoholics as compared with the Asian general population.[35] This study also demonstrates a difference in ALDH2 genotype between alcoholics and nonalcoholics among the Asian Indians. The findings are consistent with reports of a lower frequently of the ALDH2*2 allele in Japanese alcoholics, as compared with nonalcoholics.[36] The protective effect of ALDH2*2 appears to be substantially greater than that of ADH2*2 and ADH3*1 alleles.[24] Moreover, genetic factors may be of importance in determining inter individual susceptibility of alcoholic liver disease[37,38] that have observed the contribution of ADH subtypes to the overall genetic susceptibility for alcohol related problems in Caucasians, which may be very small. Eighty-two Caucasians receiving treatment for alcohol related problems were DNA typed for variants in the ADH2, ADH3 and ALDH2 gene loci. No association was found between individual or combined gene frequencies and the presence of alcohol related problems.[39] A study of the polymorphisms of alcohol metabolizing enzymes in a random female population sample (n = 756) from Novosibirsk, Siberia revealed that the ALDH2 gene was not polymorphic in this population. The frequencies of ADH2*2 and ADH3*2 alleles were 0.197 and 0.52 respectively, which is higher as compared to other Caucasoid populations (0.01-0.13 and 0.4 respectively). Reports of an association of the ADH2*2 allele with reduced ethanol consumption in Jewish men[40] and Australian men of European origin[41] support the concept that effect of ADH2 polymorphism on alcohol drinking behaviour is widespread. The distribution of ADH3 alleles is also homogous among European populations, with global frequencies of 55.3% for ADH3*1 and 441% for ADH3*3 in agreement with a previous report.[23] The fact that the allele frequencies are practically identical between alcoholic and nonalcoholic individuals suggests that the influence of ADH3 polymorphisms on predisposition to alcohol abuse is small in Europeans. The European population shows that linkage dysequilibrium between ADH2 and ADH3 are associated; therefore, the probability that both alleles are simultaneously found in an individual is higher than in the case of random allele aggregation.[42] Evidence for this allele linkage has also been found in Asian populations.[43]

The significantly lower frequency of ADH2*2, ADH3*1, and ADH2*2 alleles among alcoholic Asian Indian men can produce higher levels of acetaldehyde, through faster production or slower removal, and the even transient elevation of acetaldehyde may trigger aversive reactions. These aversive reactions may make people with these alleles less likely to become alcoholics.[9]

In the present study, it was found that total sensation seeking score, as a whole, was significantly higher in alcoholics (mean = 19.68, S.D: 4.75) as compared to controls (13.11 S.D: 2.92), which is in agreement with the previous studies that reported an association of sensation seeking with alcoholism.[44,45,46] The subscale scores of the SSS were also higher in alcoholics, which is in agreement with earlier studies.[47] This indicated that the personality patterns of being outgoing, risk-taking behaviour, certain preference for variety, need for stimulation, impulsivity and lack of inhibition was significantly higher alcohol dependent subjects as compared to normal controls.

Alcoholics as a group, showed significantly higher scores on the domains of Neuroticism (N), Extraversion (E), and openness (O) and significantly lower scores on Agreeableness (A) and Conscientiousness (C) as compared to controls. Among the alcoholics, a group of individuals emerged to have high to very high scores on all three domains of N, E, O as compared to controls and the difference was highly significant at P level < 0.001. A similar group amongst the alcoholics also had low to very low scores simultaneously on the domain of A and C as compared with controls and the difference was statistically significant at P level < 0.001. Amongst cases, 11 alcoholics were found to have both higher values in N, E, O domain and low values in A and C domains. Similar findings have been noted earlier.[12,48]

In terms of Five Factor theory of personality, the high scores of alcoholics in domain ‘N’ (Neuroticism) indicate that they have a tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety and depression. They were more impulsive and emotionally reactive as compared to nonalcoholics. This is supported by earlier studies.[12,28,49]

Extraversion is characterized by being outgoing, talkative, high on positive effect, and in need of external stimulation. According to Eysenck's arousal theory of extraversion, there is an optimal level of cortical arousal, and performance deteriorates as one becomes more or less aroused than this optimal level. Extraverts, according to Eysenck's theory, are chronically under-aroused and bored and are therefore in need of external stimulation to bring them up to an optimal level of performance. Hence, they used addictive substance as a form of stimulation.[50] The dimension of extraversion is associated with sociability, activity, assertiveness, search of stimulation, risk-taking behaviour and impulsivity.[15] Impulsivity is characterized by a lack of behavioral constraint, a lack of caution, and possibly even failure to conform to conventional moral expectations. Alcohol use and abuse are strongly discouraged by conventional cultural standards risky activities because of their illicit nature. Individuals who are low on constraint might be at increased risk of alcoholism because they are less likely to accept and be less fearful of the consequences failing to follow cultural norms governing alcohol use.[50,51]

High scores of Alcoholics on domain ‘E’ (Extraversion), in the present study, is supported by earlier studies.[28,52,53,54] However, contradictory results have been reported by some previous researches[55,56] and a recent meta-analysis.[12] On the other hand, a recent Indian study and another study from Japan supported our findings.[51,57] Extraversion was also reported to be a significant positive predictor of urge to drink.[58]

Alcoholics obtained significantly high scores on domain ‘O’ (Openness to experience). They are curious about both inner and outer worlds and have an experientially richer life. Due to this the alcoholic has initially chosen a radical action such as consumption of drugs, either for recreational use or as a means to handle an experienced problem. This is supported by earlier studies.[48,59]

Conscientiousness measures the level of control, organization, and determination. Conscientiousness is a tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement. Low scores on conscientiousness imply that they are more easily distracted and are less focused on their goals, more hedonistic and generally more lax with respect to goals. The low scores of alcoholics on consciousness, in the present study, is supported by earlier studies.[12,49,51]

Agreeableness scale reflects a tendency to compassionate and cooperation. They are good-natured, cooperative, and trustful. Agreeableness is associated with positive interpersonal qualities such as altruism and positive attitudes towards others. These are traits not commonly associated with alcoholics. Hence, a low score of alcoholics on agreeableness in the present study is on expected lines. This finding is supported by earlier studies.[12,49]

LIMITATIONS

All cases of alcohol dependence were males as the study was conducted in service personnel. Since this is not a prospective study, it is difficult to discern whether the observed differences in the personality traits are the causes or due to the results of alcohol dependence.

CONCLUSIONS

Allele frequencies of ADH2*2, ADH3*1 and ALDH2*2 were significantly low in a population of alcohol dependent Asian Indians. This finding may affect the propensity to alcoholism. Personality traits of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, and sensation seeking were significantly higher when compared to controls both on mean scores and on proportions. This indicates an association between these traits (both individually and in a cluster) and alcohol dependence with possible etiological significance. These findings may have a bearing on the etiology of alcohol dependence and intervention strategies at various stages of its evolution like initiation, continuation, and dependence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Based on AFMRC project no. 3081/2001 Alcohol and Aldehyde Dehydrogenase genotypes and personality correlates in alcohol dependence syndrome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: AFMRC.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuckit MA. Psychoactive substance use disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 1269–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begleiter H, Porjesz B. What is inherited in the predisposition toward alcoholism? A proposed model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1125–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickens RW, Svikis DS, McGue M, Lykken DT, Heston LL, Clayton PJ. Heterogeneity in the inheritance of alcoholism. A study of male and female twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:19–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250021002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurley TD, Edenberg HJ, Li TK. Pharmacogenomics: The Search for Individualized Therapies. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2002. The pharmacogenomics of alcoholism; pp. 417–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun F, Tsuritasni I, Honda R, Ma ZM, Yamada T. Association of genetic polymorphisms of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes with excessive alcohol consumption in Japanese men. Hum Genet. 1999;105:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s004399900133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SL, Chau GY, Yao CT, Wu CW, Yin SJ. Functional assessment of human alcohol dehydrogenase family in ethanol metabolism: Significance of first-pass metabolism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1132–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Zhou Z, Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Shen PH, Mulligan CJ, et al. Haplotype-based study of the association of alcohol-metabolizing genes with alcohol dependence in four independent populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:304–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng GS, Yin SJ. Effect of the allelic variants of aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH2*2 and alcohol dehydrogenase ADH1B*2 on blood acetaldehyde concentrations. Hum Genomics. 2009;3:121–7. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-3-2-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibáñez MI, Moya J, Villa H, Mezquita L, Ruipérez MA, Ortet G. Basic personality dimensions and alcohol consumption in young adults. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;48:171–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopwood CJ, Morey LC, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Yen S, Ansell EB, et al. Five factor model personality traits associated with alcohol-related diagnoses in a clinical sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:455–60. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Rooke SE, Schutte NS. Alcohol involvement and the Five-factor model of personality: A meta-analysis. J Drug Educ. 2007;37:277–94. doi: 10.2190/DE.37.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardini S, Cloninger CR, Venneri A. Individual differences in personality traits reflect structural variance in specific brain regions. Brain Res Bull. 2009;79:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa PT, Jr, MaccCrae RD. Odessa Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 1992. The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-P-I-R) and NEO five factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr . Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2010. NEO Inventories: Professional manual. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR, Dye DA. Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO personality inventory. Pers Individ Dif. 1991;12:887–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCrae RR, Terracciano A. Personality Profiles of Cultures Project. Universal features of personality traits from the observer's perspective: Data from 50 cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:547–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terracciano A, Löckenhoff CE, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L, Costa PT., Jr Personality predictors of longevity: Activity, emotional stability, and conscientiousness. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:621–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817b9371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowe RR, Kramer JR, Hesselbrock V, Manos G, Bucholz KK. The utility of the Brief MAST’ and the CAGE’ in identifying alcohol problems: Results from national high-risk and community samples. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:477–83. doi: 10.1001/archfami.6.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuckerman M, Eysenck S, Eysenck HJ. Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross cultural, age and sex comparisons. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:139–49. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basu D, Verma VK, Malhotra S, Malhotra A. Sensation seeking scale: Indian adaptation. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:155–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu YL, Carr LG, Bosron WF, Li TK, Edenberg HJ. Genotyping of human alcohol dehydrogenases at the ADH2 and ADH3 loci following DNA sequence amplifications. Genomics. 1988;2:209–14. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Buck KJ, Cunningham CL, Belknap JK. Indentifying genes for alcohol and drug sendsitivity: Recent progress and future directions. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:173–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raju MS, Chaudhury S, Sudarsanan S. Trends and issues in relation to alcohol dependence in Armed forces. Med J Armed Force India. 2002;58:143–8. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(02)80049-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhury S, Das SK, Mishra BS, Ukil B, Bhardwaj P, Bhardwaj R, et al. Physiological assessment of male alcoholism. Indian J Psychiatry. 2002;44:144–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaudhury S, Pawar AA, Bhattacharyya, Saldanha D. Hematological changes in alcohol dependence. J Marine Med Soc. 2006;8:122–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhury S, Das SK, Ukil B. Psychological assessment of alcoholism in males. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:114–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng GS, Wang MF, Chen CY, Luu SU, Chou HC, Li TK, et al. Involvement of acetaldehyde for full protection against alcoholoism by homozygosity of the variant allele of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase gene in Asians. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:463–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosron WF, Ehrig T, Li TK. Genetic factors in alcohol metabolism and alcoholism. Semin Liver Dis. 1993;13:126–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crabb DW, Edenberg HJ, Bosron WF, Li TK. Genotypes for aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency and alcohol sensitivity. The inactive ALDH2 (2) allele is dominant. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:314–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI113875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomasson HR, Edenberg HJ, Crabb DW, Mai XL, Jerome RE, Li TK, et al. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes and alcoholism in Chinese men. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:667–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osier M, Pakstis AJ, Kidd JR, Lee JF, Yin SJ, Ko HC, et al. Linkage diequillibrium at the ADH2 and ADH3 loci risk for alcoholism”. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1147–57. doi: 10.1086/302317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomasson HR1, Crabb DW, Edenberg HJ, Li TK, Hwu HG, Chen CC, et al. Low frequency of ADH*2 allele among Atayal natives of Taiwan with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:640–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higuchi S, Matsushita S, Murayama M, Takagi S, Hayashida M. Alcohol and aldehyde dehrohenase polymorphisms and risk for alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1219–21. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibuya A, Yoshida A. Genotypes of alcohol metabolizing enzymes in Japanese with alcohol liver disease. A strong association of the usual Caucasian type aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH1/2) with the disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43:744–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pirmohamed M, Kitteringham NR, Quest LJ, Allott RL, Green VJ, Gilmore IT, et al. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P44502E1 and risk of alcoholic liver diease in Caucasians with alcohol related problems and controls. Pharmocogenetics. 1995;5:351–7. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199512000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilder FJ, Hodgkinson S, Murray RM. ADH and ALDH genotype profiles in Caucasians with alcohol relatd problems and controls. Addiction. 1993;88:383–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belkovets A, Kurilovich S, Avkenstyuk A, Agarwal DP. Alcohol drinking habits and genetic polymorphisms of alcohol metabolism genes in Western Siberia. Int Hum Genet. 2001;1:151–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumark YD, Friedlander Y, Thomasson HR, Li TK. Association of the ADH2*2 allele with reduced ethanol consumption in Jewish men in Israel: A pilot study. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:133–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitfield JB, Nightingale BN, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Health AC, Martin NG. ADH genotypes and alcohol types and alcohol use in dependence in Europeans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1463–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borras E, Coutella C, Rosell A, Femandez-Muixi F, Broch M, Crosas B, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of alcohol dehydrogenase in Europeans: The ADHJ2*2 allele decreases the risk for alcoholisms and is associated with ADH3*1. Hepatology. 2000;31:984–9. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen CC, Lu RB, Chen Y, Wang MF, Chang YC, Li TK, et al. Interaction between the functional polymorphisms of the alcohol –metabolism genes in protection against alcoholism. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:795–807. doi: 10.1086/302540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson MR, Hustad JT. Personality and alcohol-related outcomes among mandated college students: Descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and college-related alcohol beliefs as mediators. Addict Behav. 2014;39:879–84. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dick DM, Aliev F, Latendresse S, Porjesz B, Schuckit M, Rangaswamy M, et al. How phenotype and developmental stage affect the genes we find: GABRA2 and impulsivity. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16:661–9. doi: 10.1017/thg.2013.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaynak O, Meyers K, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Winters KC, Arria AM. Relationships among parental monitoring and sensation seeking on the development of substance use disorder among college students. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1457–63. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Legrand FD, Goma M, Kaltenbach MA, Joly PM. Association between sensation seeking and alcohol consumption in French college students: Some ecological data collected in “open bar” parties. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:1950–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gruen C, Hooker K, Davis D. Personality and situational factors as predictors of alcohol use by college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;53:122–36. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trull TJ, Sher KJ. Relationship between the five-factor model of personality and Axis I disorders in a nonclinical population. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:350–60. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eysenck HJ, Eysenck MW. New York: Plenum; 1985. Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dubey C, Arora M, Gupta S, Kumar B. Five factor correlates: A comparison of substance abusers and non-substance abusers. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2010;36:107–14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eysenck HJ, Mohan J, Virdi PR. Personality of smokers and drinkers. J Indian Assoc Appl Psychol. 1994;20:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rao K, Ray R, Vithayathil E, Nagalakshmi SV. Personality characteristics of alcoholics dropping out of treatment. Indian J Psychiatry. 1984;26:366–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. J Pers. 2000;68:1059–88. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Porrata JL, Rosa A. Personality and psychopathology of drug addicts in Puerto Rico. Psychol Rep. 2000;86:275–80. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.86.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sher KJ, Bartholow BD, Wood MD. Personality and substance use disorders: A prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Otonari J, Nagano J, Morita M, Budhathoki S, Tashiro N, Toyomura K, et al. Neuroticism and extraversion personality traits, health behaviours, and subjective well-being: The Fukuoka Study (Japan) Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1847–55. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kambouropoulos N, Rock A. Extraversion and altered state of awareness predict alcohol cue-reactivity. J Individ Dif. 2010;31:178–84. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zilberman ML, Tavares H, el-Gubaly NE. Relationship between carving and personality in treatment – seeking women with substance – related disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]