Abstract

Background

Although the Mediterranean island of Majorca is an endemic area of leishmaniosis, there is a lack of up-to-date data on its sand fly fauna, the last report dating from 1989. The aim of the present study was to provide information on the current sand fly distribution, the potential environmental factors favoring the presence of Phlebotomus perniciosus and which areas are at risk of leishmaniosis.

Methods

In July 2008 sand fly captures were carried out in Majorca with sticky castor oil interception traps. The capture stations were distributed in 77 grids (5x5 km2) covering the entire island. A total of 1,882 sticky traps were set among 111 stations. The characteristics of the stations were recorded and maps were designed using ArcGIS 9.2 software. The statistical analysis was carried out using a bivariate and multivariate logistic regression model.

Results

The sand fly fauna of Majorca is composed of 4 species: Phlebotomus perniciosus, P sergenti, P. papatasi and Sergentomyia minuta. P. perniciosus, responsible for Leishmania infantum transmission, was captured throughout the island (frequency 69.4 %), from 6 to 772 m above sea level. Through logistic regression we estimated the probability of P. perniciosus presence at each sampling site as a function of environmental and meteorological factors. Although in the initial univariate analyses the probability of P. perniciosus presence appeared to be associated with a wide variety of factors, in the multivariate logistic regression model only altitude, settlement, aspect, drainage hole construction, adjacent flora and the proximity of a sheep farm were retained as positive predictors of the distribution of this species.

Conclusions

P. perniciosus was present throughout the island, and thereby the risk of leishmaniosis transmission. The probability of finding P. perniciosus was higher at altitudes ranging from 51 to 150 m.a.s.l., with adjacent garrigue shrub vegetation, at the edge of or between settlements, and in proximity to a sheep farm.

Keywords: Leishmaniosis, Phlebotomus perniciosus, Risk factors, Majorca Island

Background

The Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean region are considered endemic for both human and canine leishmaniosis, although the presence and prevalence of the diseases varies among the islands [1]. The first data on human leishmaniosis in the Balearic Islands date from 1925 [2], while canine leishmaniosis was first reported in 1989 [3], in both cases in the island of Majorca, where most studies have been conducted.

In certain regions of Spain, human leishmaniosis is an endemic and notifiable disease, including in the Balearic Islands, which in some years have seen the highest registered incidence in Spain (4.72 and 4.59/100,000 in 2005 and 2006 respectively) [4]. Between 7 and 33 cases are declared in Majorca every year [5, 6]. As in other parts of Spain, the disease is under-reported, especially cases of cutaneous leishmaniosis [7]; cases of human cryptic leishmaniosis have also been described [8]. Little information is available on the origin of cases [6, 8].

The heterogeneous distribution and prevalence of canine leishmaniosis (CanL) ranges from 0% to 45% among different studies and islands [9–11]. A study conducted by the sanitary authorities in Majorca gave a prevalence of 14.4 % [3]. Veterinarians answering a questionnaire on CanL trends in Majorca thought the disease was stable [1] and that autochthonous cases continue to occur, as has been previously described [3, 11].

Data on sand fly distribution in the Balearic Islands is scarce [10, 12–15]. The most recent data for Majorca corresponds to studies performed in 1987 and 1989 [14], but do not include information about the distribution and density of the different sand fly species throughout the island.

The aim of the present study was to obtain up-to-date entomological data by standardized methods that could be compared with data reported by other teams in different geographical areas of Europe and used in future entomological studies, including those on climate change. In addition, the extensive capture of the vector in the island could provide information on the environmental factors that may potentially favour the presence of P. perniciosus and also which areas are at risk of leishmaniosis.

Methods

Area of study

The study was carried out on the island of Majorca (Spain), located at 39°15’ to 39°60’N, 2°20’ to 3°30’E. Majorca is the largest of the Balearic Islands, covering 3,640 km2 and with a coastline of 623 km. Altitudes range from sea level to 1,445 m.a.s.l., most of the island (78.8%) being below 200 m.a.s.l. and only 6.3% above 500 m.a.s.l. The highest mountainous area is the Serra de Tramuntana in the north, which runs parallel to the west coast, protecting the island from the prevailing west and northwest winds. Bordering the low central plain in the southeast is the Serra de Llevant, with a maximum altitude of 509 m.a.s.l. [16].

The climate is typically Mediterranean, with long periods of invariability. The mean annual temperature is about 16–17°C, except in the Serra de Tramuntana, where it drops to 13°C. In the coldest period (1–3 months), the average temperature is about 5-10°C, with an average minimum on winter nights of 5–9°C, while in the hottest period (5–8 months) it is above 15-20°C, with an average diurnal maximum of 29-31°C. The mean relative humidity is 74%. Annual rainfall oscillates from a maximum in autumn (66.9 mm) to a minimum in summer (8.6 mm), with an annual average of 481.6 mm. Considerable differences exist between mountainous regions (up to 1,200 mm) and the arid south (less than 400 mm).

Holm oak (Cyclamini-Quercetum ilicis) grows everywhere on the island below 1000 m.a.s.l, but under the influence of man it has largely been replaced by pine (Pinus halepensis), which is now the dominant woodland tree, including all well-conserved beaches. In areas below 500–700 m.a.s.l., with annual precipitations of less than 600 mm, the wild olive tree predominates, while above 1000 m.a.s.l, the vegetation is low and adapted to strong winds. The extensive cultivated land consists principally of almond and olive trees, vineyards and cereals.

The island has two bioclimatic zones: meso-Mediterranean (T: average annual temperature 13–17°C; m: average minimum temperature of the coldest month -1 to -4°C; M: average maximum temperature of the coldest month 9 - 14°C; Ti: thermicity index 210–350), where oaks predominate (Cyclamini-Quercetum ilicis), and thermo-Mediterranean (T: 17–19°C; m: 4–10°C; M: 14 - 18°C; Ti: thermicity index from 350–470) with maquis (Cneoro-Ceratonietum)) [16, 17].

Capture of sand flies

In July 2008 sand fly captures were carried out in Majorca with sticky castor oil interception traps (20×20 cm) set for 4 days according to the standardized methodology implemented in the EDEN project (EU) [18–21]. The sampling sites consisted of holes used to drain embankments or containment walls, which were considered to be likely diurnal resting places for adult sand flies [22]. The capture stations were distributed in 77 grids (5×5 km2), almost one station per grid, covering the entire island. A total of 1,882 sticky traps were set, representing an adhesion surface of 150.56 m2 distributed among 111 stations (Figure 1).

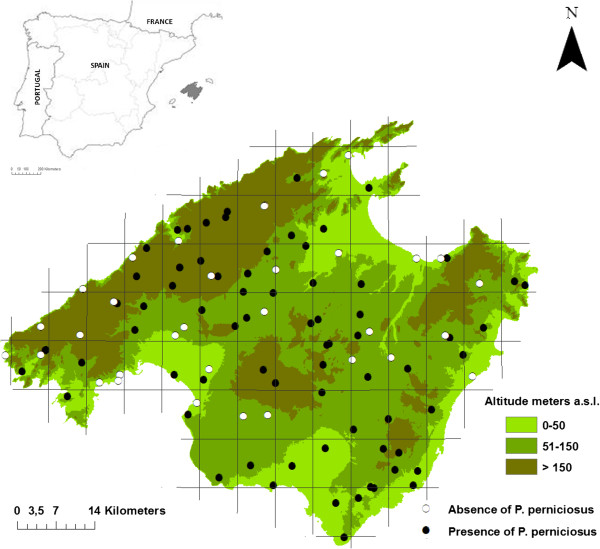

Figure 1.

Sampling sites in Majorca showing the presence/absence of P. perniciosus and altitudinal ranges of the island.

Data collection and environmental and meteorological variables

The characteristics of the stations, including location, habitat, environment and fauna, were recorded on a PDA (Palm Tungsten T5) using Pendragon Form v.5.0 software (PSC, Libertyville, IL, USA) and GPS (Tom Tom Wireless GPS MK II). Maps were designed using ArcGIS 9.2 software (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA).

Climate variables were provided by the Spanish Meteorological Agency (AEMet) from the 43 meteorological stations in the study area. Different periods were considered for the meteorological variables: i) Period 1 (Sampling Day 1, when traps were set, to Day 4, when traps were recovered) and ii) Period 2 (the month before Sampling Day 1). Climate data from the nearest meteorological station were assigned to each sampling site for periods 1 and 2 using the spatial join-and-relate tool of ArcGis v.9.2 software and included: wind speed (Km/h), mean relative humidity (%), average rainfall (mm), and mean daily T (°C). The average minimum T (°C) in winter was also assigned.

Altitude data for each geocoded collection site were extracted from a 90 m resolution CGIAR Digital Elevation Model [23] using ArcGIS 9.2 software.

The presence of animals was studied in two ways: taking into account the animals or animal signs observed during captures, and using databases provided by the Col · legi Oficial de Veterinaris de les Illes Balears (canine census and livestock farms). In the latter, data from the closest station were assigned for each sampling site as described for the meteorological stations. A human census was obtained from municipal data.

Sand fly processing and identification

Sand flies were processed as previously described [1]. Briefly, sand flies were removed from the sticky traps with a brush and fixed in 96% ethanol and then in 70% alcohol until identification. Males and Sergentomyia spp. females were observed and identified under the stereo microscope. Females of the genus Phlebotomus were mounted on glass slides in Hoyer medium and identified on the basis of morphological characteristics in an optical microscope using the keys of Gállego [24].

Statistical analysis

For the study 57 variables were taken into account, including the habitat and environmental characteristics of the capture stations, fauna, demography and climate.

Bivariate logistic regression studies were conducted using the SPSS 20.0 software for Windows, with all the independent variables set against the presence/absence of P. perniciosus as the dependent variable. The majority were used as categorical variables, except those related to meteorological conditions. Continuous variables such as the human and canine census were categorized in the search for association with the dependent variable. The possibility of interaction and/or confusion between different variables was examined by constructing and comparing different logistic regression models [19].

To construct the multivariate model, all the variables with p <0.2 in the bivariate study were used. In the final multivariate model, variables with p ≤0.05 were retained.

Results

88.2 % of the traps placed on the island of Majorca were recovered, representing a surface of 135.68 m2. A total of 14,412 specimens were captured, with 4 species identified (Table 1): Phlebotomus pernicious, P. sergenti, P. papatasi and Sergentomyia minuta.

Table 1.

Quantitative results of the sand fly fauna of Majorca. M: males, F: females

| Species | Sex. ratio (M:F) | Abundance (%) | Density (n/m 2) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. perniciosus | 4:1 | 6.3 | 6.72 | 69.37 |

| P. sergenti | 24:1 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 12.61 |

| P. papatasi | 3:0 | 0.2 x 10-3 | 0.02 | 0.9 |

| S. minuta | 1.4:1 | 93.5 | 99.3 | 92.8 |

Among the mamophilic species, P. perniciosus was captured throughout the island in 77 of the 111 stations prospected, at 6 to 772 m.a.s.l. (Figure 1), with climate conditions during the capture period of 19.6-27.4°C, 55.5-86.4% relative humidity, 0–42 mm pluviometry and 3.1-17.1 km/h wind speed. P. sergenti and P. papatasi were captured in only 14 and 1 of the stations, respectively, and always in a low number. P. ariasi was not found anywhere on the island.

Bivariate analysis

The bivariate analysis of the factors associated with the presence of P. perniciosus gave results of p <0.2 for 24 of the variables, which were taken into account in the multivariate analysis. 12 of these variables showed significant association (p <0.05) with the sand fly presence in both bivariate and multivariate analyses (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk factors for the presence of Phlebotomus perniciosus in Majorca: Bivariate logistic regression model

| Number of stations (111) | Odds ratio (I.C. 95 %) | p - Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude (m.a.s.l.) | 0.063 | ||

| 0-50 | 28 | Ref. | |

| 51-150 | 60 | 3.133 (1.195 – 8.214) | 0.020 |

| >150 | 23 | 1.625 (0.522 – 5.055) | 0.402 |

| Settlement | |||

| Within settlement | 21 | Ref. | |

| Edge of/between settlements | 90 | 5.339 (1.950 – 14.617) | 0.001 |

| Type of roadway | 0.228 | ||

| Paved public road | 46 | Ref. | |

| Paved drive | 41 | 2.903 (1.100 – 7.658) | 0.031 |

| Unpaved track | 9 | 2.463 (0.460 – 13.182) | 0.292 |

| Garden (in rural village and other settlement) | 5 | 2.815 (0.291 – 27.206) | 0.371 |

| Property (farm and other) | 10 | 1.056 (0.262 – 4.258) | 0.939 |

| Site category | 0.421 | ||

| Embankment drainage holes | 19 | Ref. | |

| Wall drainage holes (not embankment) | 26 | 2.111 (0.204 – 0.843) | 0.031 |

| Other holes in walls (not embankment) | 47 | 0.308 (0.062 – 1.522) | 0.148 |

| Natural rock crevices | 3 | 0.235 (0.014 – 3.917) | 0.313 |

| Farm buildings (holes) | 13 | 0.264 (0.040 – 1.735) | 0.166 |

| Sewer/drainage openings | 3 | - | 0.999 |

| Aspect | 0.26 | ||

| Other (all orientations except south-east and west facing) | 73 | Ref. | |

| South-east facing | 15 | 2.990 (0.623 – 14.350) | 0.171 |

| West facing | 23 | 0.716 (0.271 – 1.892) | 0.500 |

| Slope | 0.843 | ||

| None | 79 | Ref. | |

| Shallow (<10 %) | 30 | 1.018 (0.407 – 2.546) | 0.969 |

| Steep (>10 %) | 2 | 0.436 (0.026 – 7.270) | 0.563 |

| Shelter | 0.776 | ||

| Not sheltered | 93 | Ref. | |

| Sheltered | 17 | 1.548 (0.465 – 5.149) | 0.476 |

| Unsure | 1 | - | 1,000 |

| Water course | |||

| None | 105 | Ref. | |

| Natural | 6 | 0.419 (0.080 – 2.191) | 0.303 |

| Wall construction | 0.013 | ||

| Stone without mortar | 48 | Ref. | |

| Stone/mortar | 16 | 0.338 (0.101 – 1.133) | 0.079 |

| Brick/mortar | 30 | 0.263 (0.097 – 0.714) | 0.009 |

| Other | 17 | 1.974 (0.386 – 10.089) | 0,414 |

| Drain hole construction | |||

| Plastic pipe | 35 | Ref. | |

| Other (unlined, cement pipe) | 76 | 2.250 (0.964 – 5.249 | 0.061 |

| Hole interior | 0.961 | ||

| Bare | 33 | Ref. | |

| Dusty (bare) | 68 | 0.784 (0.313 – 1.966) | 0.604 |

| Dusty (with vegetation) | 3 | 0.750 (0.060 – 9.319) | 0.823 |

| Soil (with vegetation) | 7 | 0.938 (0.153 – 5.728) | 0.944 |

| Vegetation on the wall | |||

| No | 86 | Ref. | |

| Yes | 25 | 1.529 (0.550 – 4.251 | 0.416 |

| General environment | 0.02 | ||

| Rural village | 48 | Ref. | |

| Rural agriculture and forestry | 45 | 2.977 (1.095 – 8.091) | 0.032 |

| Coastal village | 8 | 0.548 (0.122 – 2.475) | 0.435 |

| Other settlement (non rural or non coastal village) | 10 | 0.366 (0.090 – 1.478) | 0.158 |

| General vegetation (100 m – 1Km) | 0.178 | ||

| Aleppo pine | 51 | Ref. | |

| Evergreen oaks | 3 | 0.273 (0.023 – 3.219) | 0.302 |

| Garrigue shrubs | 38 | 2.416 (0.888 – 6.575) | 0.084 |

| None | 19 | 0.935 (0.313 – 2.795) | 0.904 |

| Adjacent flora | 0.02 | ||

| Aleppo pine and evergreen oaks | 30 | Ref. | |

| Garrigue shrubs | 40 | 14.529 (2.949 – 71.587) | 0.001 |

| None | 41 | 0.885 (0.343 – 2.284) | 0.801 |

| Land cover (Corine) | 0.006 | ||

| Urban area | 33 | Ref. | |

| Agricultural area | 62 | 5.525 (2.113 – 14.448) | <0.001 |

| Forest area | 15 | 1.594 (0.462 – 5.497) | 0.461 |

| Humid area | 1 | - | 1.000 |

| Arable | 0.107 | ||

| Cereals | 35 | Ref. | |

| Root crop | 2 | 0.167 (0.009 – 3.118) | 0.231 |

| Other (non cereal or root crop) | 6 | 0.333 (0.048 – 2.328) | 0.268 |

| None | 68 | 0.269 (0.093 – 0.781) | 0.016 |

| Garden | 0.385 | ||

| Grass, shrubs and trees | 36 | Ref. | |

| Paved hard surface | 8 | 1.333 (0.276 – 6.442) | 0.720 |

| Orchard | 56 | 2.187 (0.903 – 5.294) | 0.083 |

| None | 11 | - | 0.999 |

| Bioclimatic | |||

| Meso-Mediterranean | 63 | Ref. | |

| Thermo-Mediterranean | 48 | 1.130 (0.499 – 2.559) | 0.770 |

| Demographic data | |||

| Humans | |||

| ≥ 688,5 | 106 | Ref. | |

| ≤ 688,4 | 5 | 0.276 (0.044-1.731) | 0.169 |

| Canine | |||

| ≤ 1989 | 56 | Ref. | |

| ≥ 1990 | 55 | 0.693 (0.308-1.561) | 0.376 |

| Animals seen** | |||

| Dogs | |||

| Yes | 56 | 0.583 (0.258 – 1.321) | 0.196 |

| Cats | |||

| Yes | 9 | 1.600 (0.315 – 8.135) | 0.571 |

| Pet animals (dogs and cats) | |||

| Yes | 56 | 0.615 (0.272 – 1.391) | 0.243 |

| Equine | |||

| Yes | 7 | 2.789 (0.323 – 24.107) | 0.351 |

| Cattle | |||

| Yes | 2 | 0.434 (0.026 – 7.153) | 0.560 |

| Goat | |||

| Yes | 3 | 0.880 (0.077 – 10.047) | 0.918 |

| Sheep | |||

| Yes | 23 | 1.769 (0.597 – 5.242) | 0.303 |

| Pig | |||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1.000 |

| Farm animals seen | |||

| Yes | 32 | 1.472 (0.582 – 3.721) | 0.414 |

| Rabbit | |||

| Yes | 2 | - | 0.999 |

| Chicken | |||

| Yes | 13 | 2.667 (0.558 – 12.750) | 0.219 |

| Duck | |||

| Yes | 2 | - | 0.999 |

| Pigeon | |||

| Yes | 5 | 0.649 (0.103 – 4.070) | 0.644 |

| Pen animals seen (Chicken, duck and pigeon) | |||

| Yes | 17 | 1.523 (0.458 – 3.066) | 0.492 |

| Livestock farms near*** | |||

| Horse | |||

| Yes | 44 | 0.540 (0.238 – 1.225) | 0.140 |

| Sheep | |||

| Yes | 58 | 2.720 (1.177 – 6.289) | 0.019 |

| Goat | |||

| Yes | 9 | 1.600 (0.315 – 8.135) | 0.571 |

| Pigs | |||

| Yes | 34 | 1.087 (0.450 – 2.624) | 0.853 |

| Rabbit | |||

| Yes | 7 | 0.304 (0.064 – 1.441) | 0.134 |

| Bovine | |||

| Yes | 4 | 0.427 (0.058 – 3.163) | 0.405 |

| Chicken | |||

| Yes | 23 | 0.786 (0.297 – 2.080) | 0.628 |

| Turkey | |||

| Yes | 4 | 0.136 (0.014 – 1.358) | 0.089 |

| Pigeon | |||

| Yes | 7 | 0.155 (0.028 – 0.842) | 0.031 |

| Pheasant | |||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1 |

| Quail | |||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1 |

| Partridge | |||

| Yes | 1 | - | 1 |

| Bees | |||

| Yes | 5 | 0.099 (0.011 – 0.919) | 0.042 |

| Meteorological variables (continuous)* | |||

| Wind period 1 | 3.1 – 17.1 | 0.937 (0.856 – 1.025) | 0.157 |

| Wind period 2 | 3.1 – 15 | 0.952 (0.854 – 1.062) | 0.381 |

| Humidity period 1 | 55.5 – 86.4 | 0.956 (0.907 – 1.008) | 0.099 |

| Humidity period 2 | 74.7 – 96.7 | 0.952 (0.881 – 1.028) | 0.207 |

| Rainfall period 1 | 0 – 42 | 0.954 (0.897 – 1.013) | 0.126 |

| Rainfall period 2 | 0 – 511 | 1.000 (0.996 -1.004) | 0.936 |

| Temperature period 1 | 19.6 – 27.5 | 0.911 (0.722 – 1.149) | 0.432 |

| Temperature period 2 | 19.8 – 26.2 | 0.974 (0.756 – 1.253) | 0.835 |

| Wintry temperature | -2.6 – 5.3 | 1.068 (0.857 – 1.331) | 0.560 |

Dependent variable presence/absence of P. perniciosus. Ref. Reference category. C. I. = Confidence interval. Period 1: sampling day 1(traps set) today 4 (traps recovered). Period 2: the month before sampling day 1. *N is substituted by minimum and maximum values. **Reference category Animals seen: No. ***Reference category Livestock farms near: No.

The probability of capturing P. perniciosus was significantly higher at 51 – 150 m.a.s.l. (O.R. = 3.13), at the edge of or between settlements (O.R = 5.3), on a paved drive (O.R. = 2.90), in a wall drainage hole (not embankment) (O.R. = 2.11), in a general rural agricultural or forestry habitat (O.R. = 2.98), with adjacent flora of garrigue shrubs (O.R. = 14.53), in an agricultural area (O.R. = 5.52), and in the proximity of a sheep farm (O.R. = 2.72).

In contrast, the probability of capturing P. perniciosus showed a negative correlation with walls of bricks and mortar (O.R. = 0.26), non arable areas (O.R. = 0.27) and the proximity of pigeon and bee farms (O.R. = 0.15 and 0.1, respectively) (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis

To construct the multivariate model, all the 24 variables with p <0.2 in the bivariate study were used. The variables that make up the multivariate logistic regression model and are shown to be the best predictors of the presence/absence of P. perniciosus are: an altitude of 51–150 m.a.s.l. (p = 0.01, O.R. = 8.6), location of the sampling sites at the edge of or between villages (p = 0.08, O.R. = 8.08), a south east orientation (p = 0.018, O.R. = 34.97), the absence of drainage holes with plastic pipes (p = 0.05, O.R. = 3.45), adjacent flora of garrigue shrubs (p = 0.001, O.R. = 38.05) and the proximity of a sheep farm (p = 0.001, O.R. = 20) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk factors for the presence of Phlebotomus perniciosus in Majorca: Multivariate logistic regression model

| Odds ratio (I.C. 95 %) | p - Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Altitude (m.a.s.l.) | 0.019 | |

| 0-50 | Ref. | |

| 51-150 | 8.653 (1.514 – 49.441) | 0.015 |

| >150 | 0.805 (0.131 – 4.964) | 0.816 |

| Settlement | ||

| Within settlement | Ref. | |

| Edge of/between settlement | 8.080 (1.737 – 37.596) | 0.008 |

| Aspect | 0.03 | |

| Other (all orientations except south-east and west facing) | Ref. | |

| South-east-facing | 34.975 (1.817 – 673.425) | 0.018 |

| West-facing | 0.457 (0.116 – 1.798) | 0.263 |

| Drainage hole construction | ||

| Plastic pipe | Ref. | |

| Other (unlined, cement pipe) | 3.451 (1.002 – 11.880) | 0.050 |

| Adjacent flora | 0.001 | |

| Aleppo pine and evergreen oaks | Ref. | |

| Garrigue shrubs | 38.051 (4.900 – 295.469) | 0.001 |

| None | 1.308 (0.323 – 5.307) | 0.707 |

| Sheep farm near | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 19.989 (3.557 – 112.322) | 0.001 |

Dependent variable presence/absence of P. perniciosus. Ref. Reference category. C. I. = Confidence interval. R2 = 0.571.

Discussion

Four out of the five species previously reported for the island of Majorca (P. perniciosus, P. ariasi, P. sergenti, P. papatasi and S. minuta) [4, 12–14, 25] were captured. Although P. ariasi is cited [4, 13, 25], we were unable to capture this species despite sampling the whole island from 0 to 772 m.a.s.l and using a large number of traps. In Europe P. ariasi has been found at altitudes ranging from 10 m up to 2000 m.a.s.l. [20, 26], showing a preference for sub-humid or humid areas with cold winters (supra-Mediterranean) [21, 22, 27], while Majorca has a semi-arid and sub-humid climate with mild summers (meso- and thermo-Mediterranean). The repeated reporting of P. ariasi in Majorca may stem from an erroneous citing, which has been duplicated in other publications. Nevertheless, in this study, although captures were made throughout the whole island, they were restricted to the month of July (2008). Therefore, in order to assess more accurately whether P. ariasi is present or absent from the island, captures need to be made at different periods of sand fly activity. Also, intensive studies using CDC light traps should be carried out over 700 m a.s.l. in the mountainous regions of the island, particularly the area of the Serra de Tramuntana.

Among the species found, only P. perniciosus is a vector of L. infantum, and is responsible for human and canine leishmaniosis in the Mediterranean region [28, 29], while P. sergenti and P. papatasi are proven vectors of other Leishmania species in the Old World that are not present in Spain (L. tropica and L. major, respectively) [7, 30–32].

The most common sand fly species in Majorca is S. minuta, followed by P. perniciosus, P. sergenti and P. papatasi. The capturing method may have influenced the abundance level of each species, since it is known that sticky traps favor the capture of S. minuta females, which could be due to the feeding habits of this herpetophilic species and its preferred resting sites [24, 26]. Not enough P. sergenti and P. papatasi were captured for a statistical analysis of the factors affecting their presence in Majorca. As mentioned previously, most of the island is below 200 m.a.s.l., with a semi-arid climate, which are ideal conditions for P. sergenti to occur [33–35], yet this species was found at a low frequency (12.6 %). In other areas of Spain [35], P. sergenti has been found at altitudes of 0–1,153 m.a.s.l. and in the same type of meso- and thermo-Mediterranean bioclimates as in Majorca. Perhaps the location of traps within urbanized settlements (21 stations) or at the edge of/between settlements (90 stations), with little or no presence of humans, influenced the results, since P. sergenti is a peridomestic and anthropophilic species found in rural villages [30] and rare in intensely urban areas [36]. The other scarcely sampled species, P. papatasi, prefers peri-arid and Saharan environments [33], not present in Majorca.

P. perniciosus was captured in Majorca from 6 to 772 m a.s.l., the maximum altitude at which the sticky traps were placed, since above that there was a lack of appropriate locations for setting traps. In Europe, the species occupies sites from sea level to 1534 m a.s.l. [19, 20, 26]. The probability of finding P. perniciosus was significantly higher at altitudes of 51 – 150 m.a.s.l., both in the bivariate and multivariate analysis. Stations at 0 – 50 m.a.s.l. were located in breezy coastal areas and sand flies are very sensitive to windy conditions [26, 29, 30]. In locations at 51 – 150 m.a.s.l. the adjacent flora consisted principally of garrigue shrubs, where the probability of finding P. perniciosus is significantly higher.

Locations between or at the edge of settlements favored the presence of P. perniciosus compared to those within settlements, as found in other studies [1, 18, 19, 21], which would indicate that urban environments are not suitable for P. perniciosus. The barbicans and other locations where sticky traps were placed constituted resting sites, which are often near the larval breeding sites [22, 26, 29]. In agreement with the site location, a positive correlation was obtained with a rural agricultural and forestry environment, where the probability of finding P. perniciosus was 3 times higher than in a rural village, as well as with an area of agricultural land cover, where the probability was more than 5 times higher than in urbanized areas. These results also match the negative correlation found in non-arable points of capture, usually in rural and/or urbanized areas, where the probability of capturing P. perniciosus decreased in comparison with stations near arable areas (cereals). In non-urbanized areas the terrestrial cycle of immature forms would be favored, and the females would have more access to suitable oviposition sites [18, 21]. In addition, the deployment of insecticides in urbanized areas during the summer period when blood-sucking insects are active would reduce the population of sand flies in those settlements, and it is considered a way of controlling leishmaniosis [37].

The presence of animals near the sampling site increased the probability of encountering P. perniciosus, for several reasons: i) the presence of animal excrements would constitute a good sand fly breeding substrate; ii) sand flies have a poor capacity for flying and dispersing far from their breeding sites (usually 300 m and rarely more than1 km) [26, 29, 30], which may explain the existence of small localized populations [38]; and iii) P. perniciosus exhibits opportunistic feeding behavior [39–42]. Nevertheless, in contrast with previous studies [1, 18, 19], no correlation was found with the presence of animals or animal traces such as feces near the trapping sites, only with an abundance of animals in livestock farms. Not all livestock species attract P. perniciosus in the same way [19], and its capture increased significantly when sheep farms were near to the sampling site. Notably, sheep farms contain a greater number of animals that remain outside overnight, when sand flies are active. No demographic influence of humans or dogs was found, probably because the stations with the highest presence of P. perniciosus were located between villages, away from urban settlements.

Some other variables correlated with the presence of P. perniciosus only in the bivariate analysis, such as the type of road, site category, land cover, wall construction and arable area, while the type of drainage hole correlated only in the multivariate analysis. The probability of capturing P. perniciosus in a paved drive was 2.9 times higher than in a paved public road, where greater car traffic would disturb sand flies. Drainage holes in non-embankment walls favored the presence of P. perniciosus in contrast with those in embankments, probably because the former have no air currents. On the contrary, the presence of P. perniciosus decreased by 75% in stone or brick walls with mortar, probably because these have fewer suitable resting places than walls without mortar. As described elsewhere, the use of PVC in drainage holes decreased the probability of finding P. perniciosus and could be considered as a control method to reduce leishmaniosis transmission [19].

The influence of climate variables on the distribution and activity of sand flies has been repeatedly reported [26, 30, 31, 43]. In contrast with other reports [18, 19, 21, 41], in the current study in Majorca, climate variables did not affect the probability of finding P. perniciosus, probably due to the short period of time when captures were performed (July 2008) and the homogenous geographical conditions of most trapping sites. It should also be taken into account that the island of Majorca has a Mediterranean climate, which remains highly stable over long periods, with the exception of the mountainous areas, and captures were not made over 700 m.a.s.l., due to the absence of appropriate places to set traps. More studies involving periodic captures throughout the summer, or over one year are required, as has been done in another Balearic island (Minorca) [1], to obtain more data on the influence of climate conditions on sand fly distribution.

The presence of P. perniciosus in Majorca is a health issue since it is a vector of L. infantum in the Mediterranean area. Leishmaniosis poses a risk not only for the habitual inhabitants of the island, but also for the large numbers of tourists visiting in the summer, coinciding with the period of vector activity. In addition, these tourists often travel with their pets, which are at risk of developing CanL. In central and northern European countries cases of leishmaniosis have repeatedly been reported in humans and dogs that have visited endemic areas [43–45]. Recent accounts of sand flies with a proven or suspected capacity to transmit L. infantum in non-endemic areas [46, 47], together with the arrival of infected persons and animals, would favor the possibility of autochthonous transmission in new areas, as has been reported in the island of Minorca [1].

Conclusion

The sand fly fauna in Majorca is composed of four species: P. perniciosus, P. sergenti, P. papatasi and S. minuta. The distribution of P. perniciosus extends throughout the island, from sea level to the mountains, being present in 70 % of the capture sites. This suggests that a risk of leishmaniosis transmission exists all over the island, and the presence of tourists during the period of P. perniciosus activity could favor the dispersion of the disease to other countries. The probability of finding P. perniciosus was higher at altitudes ranging from 51 to 150 m.a.s.l., with adjacent garrigue shrub vegetation, at the edge of or between settlements, and in proximity to a sheep farm.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants of the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología of Spain (CGL2007-66943-C02-01/BOS), Departament d’Universitats, Recerca i Societat de la Informació de la Generalitat de Catalunya (Spain) (2009SGR385). The Spanish Meteorological Agency (AEMet) provided the meteorological data for the study. Thanks to Anna Lanau for her assistance in placing traps and collecting sand flies. We are also grateful for the help of the Col · legi Oficial de Veterinaris de les Illes Balears, especially R. García and A. Figueroa. MMA was awarded a contract in the Spanish project.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Authors’ contributions

MGC, MPV, MMAA designed and supervised the study. MGC, CBF, TSF, SCG, MMAA undertook field and laboratory activities. MGC, JMS, MMAA analyzed the data and carried out the statistical analysis, MGC, MPV, JMS, MMAA drafted and revised the manuscript. All the authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

M Magdalena Alcover, Email: mmagdalenaalcoveramengual@ub.edu.

Cristina Ballart, Email: cristina.ballart@cresib.cat.

Joaquina Martín-Sánchez, Email: joaquina@ugr.es.

Teresa Serra, Email: serrafarell@gmail.com.

Soledad Castillejo, Email: scastillejo@ub.edu.

Montserrat Portús, Email: mportus@ub.edu.

Montserrat Gállego, Email: mgallego@ub.edu.

References

- 1.Alcover MM, Ballart C, Serra T, Castells X, Scalone A, Castillejo S, Riera C, Tebar S, Gramiccia M, Portús M, Gállego M. Temporal trends in canine leishmaniosis in the Balearic Islands (Spain): A veterinary questionnaire. Prospective canine leishmaniosis survey and entomological studies conducted on the Island of Minorca, 20 years after first data were obtained. Acta Trop. 2013;128:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pittaluga G. Etude épidémiologique sur la “Leishmaniose viscérale” en Espagne. Rapport présentée à l’Organisation d’Hygiène de la Société des Nations (8 octobre 1925) Genève: Societé des Nations 1700 (P) 10/25; 1925. p. 1700. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matas-Mir B, Rovira-Alos J. Estudio epidemiológico de la leishmaniosis canina en la isla de Mallorca. Palma de Mallorca: Conselleria de Sanitat i Seguretat Social del Govern Balear; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amela C, Suarez B, Isidoro B, Sierra MJ, Santos S, Simón F. Evaluación del riesgo de transmisión de Leishmania infantum en España. Madrid: Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias sanitarias (CCAES), Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xarxa de Vigilància Epidemiològica de les Illes Balears . Informe 2012. Palma de Mallorca: Conselleria de Salut, Direccio General de Salut Publica i Consum, Govern de les Illes Balears; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulls setmanals de Vigilància Epidemiològica . Fulls setmanals de Vigilància Epidemiològica. Palma de Mallorca: Servei d’Epidemiologia, Direcció General de Salut Pública i Consum, Conselleria de Salut del Govern Balear; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den Boer M, the WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team Leishmaniasis Worldwide and Global Estimates of Its Incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riera C, Fisa R, López-Chejade P, Serra T, Girona E, Jiménez MT, Muncunill J, Sedeño M, Mascaró M, Udina M, Gállego M, Carrió J, Forteza A, Portús M. Asymptomatic infection by Leishmania infantum in blood donors from the Balearic Islands (Spain) Transfusion. 2008;48:1383–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvar J. Las Leishmaniasis: de la Biología al Control. Salamanca: Laboratorios Intervet S.A; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seguí MG. Estudi epidemiològic de la leishmaniosis a l’illa de Menorca. Revista de Menorca. 1991;2:153–178. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pujol A, Cortés E, Ranz A, Vela C, Aguiló C, Martí B. Estudi de seroprevalència de leishmaniosi i d’ehrlichiosi a l’illa de Mallorca. Revista del Col legi Oficial de Veterinaris de les Illes Balears Veterinària. 2007;32:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gil Collado J. Écologie des Leishmanioses, Montpellier 1974. Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique N. 239. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; 1977. Phlébotomes et leishmanioses en Espagne; pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil-Collado J, Morillas-Márquez F, Sanchís-Marin MC. Los flebotomos en España. Rev San Hig Pub. 1989;63:15–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lladó MT, Rotger MJ. Estudio del flebotomo como vector de la leishmaniasis en la isla de Mallorca. Palma de Mallorca: Conselleria de Sanitat i Seguretat Social del Govern Balear; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molina R, Aransay A, Nieto J, Cañanvate C, Chicharro C, Sans A, Flores M, Cruz I, García E, Cuadrado J, Alvar J. The Phlebotomine sand flies of Ibiza and Formentera Islands (Spain) Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 2005;82:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Bolós i Capdevila O. La vegetació de les Illes Balears. Comunitat de plantes. 2. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivas–Martínez S. Memoria del mapa de series de vegetación de España. Pesca y Alimentación. I.C.O.N.A: Ministerio de Agricultura; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gálvez R, Descalzo MA, Miró G, Jiménez MI, Martín O, Dos Santos-Brandao F, Guerrero I, Cubero E, Molina R. Seasonal trends and spatial relations between environmental/meteorological factors and leishmaniosis sand fly vector abundances in Central Spain. Acta Trop. 2010;115:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barón SD, Morillas-Márquez F, Morales-Yuste M, Díaz-Sáez V, Irigaray C, Martín-Sánchez J. Risk maps for the presence and absence of Phlebotomus perniciosus in an endemic area of leishmaniasis in southern Spain: implications for the control of the disease. Parasitology. 2011;138:1234–1244. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballart C, Barón S, Alcover MM, Portús M, Gállego M. Distribution of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Andorra: First finding of P. perniciosus and wide distribution of P. ariasi. Acta Trop. 2012;122:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballart C, Guerrero I, Castells X, Barón S, Castillejo S, Alcover MM, Portús M, Gállego M. Importance of individual analysis of environmental and climatic factors affecting the density of Leishmania vectors living in the same geographical area: the example of Phlebotomus ariasi and P. perniciosus in Northeast Spain. Geospat Health. 2014;8:367–381. doi: 10.4081/gh.2014.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rioux JA, Carron S, Dereure J, Périères J, Zeraia L, Franquet E, Babinot M, Gállego M, Prudhomme J. Ecology of leishmaniasis in the South of France. 22. Reliability and representativeness of 12 Phlebotomus ariasi, P. perniciosus and Sergentomyia minuta (Diptera: Psychodidae) sampling stations in Vallespir (eastern French Pyrenees region) Parasite. 2013;20:34. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2013035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarvis A, Reuter HI, Nelson A, Guevara E. Hole – filled seamless SRTM data V4. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gállego J, Botet J, Gállego M, Portús M. Los flebotomos de la España peninsular e Islas Baleares. Identificacióny corología. Comentarios sobre los métodos de captura. In: Hernández S, editor. Memoriam al Prof. Dr. D. F. de P. Martínez Gómez. Córdoba: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba; 1992. pp. 581–600. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucientes J, Castillo JA, Gracia MJ, Peribáñez MA. Flebotomos, de la biología al control. Revista Electrónica de Veterinaria REDVET. 2005;6:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rioux JA, Golvan YJ. Épidémiologie des Leishmanioses dans le Sud de la France. Paris: Monographies de l’Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. N° 37; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aransay AM, Testa JM, Morillas-Marquez F, Lucientes J, Ready PD. Distribution of sandfly species in relation to canine leishmaniasis from the Ebro Valley to Valencia, northeastern Spain. Parasitol Res. 2004;94:416–420. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gállego M. Zoonosis emergentes por patógenos parásitos: las leishmaniosis. Rev Sci Tech. 2004;23:661–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:123–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Killick-Kendrick R. The biology and control of Phlebotomine sand flies. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17:279–289. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(99)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ready PD. Leishmaniasis emergence in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO Control of the leishmaniases.: Report of a WHO expert committee. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 2010;949:1–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rioux JA, Rispail P, Lanotte G, Lepart J. Relation Phlébotomes-bioclimats en écologie des leishmanioses. Corollaires épidémiologiques. L’exemple du Maroc. Bulletin de la Société botanique de France. 1984;131:549–557. doi: 10.1080/01811789.1984.10826694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gállego M, Rioux JA, Rispail P, Guilvard E, Gállego J, Portús M, Delalbre A, Bastien P, Martínez-Ortega E, Fisa R. Primera denuncia de flebotomos (Diptera, Psychodidae, Phlebotominae) en la provincia de Lérida (España, Cataluña) Rev Iber Parasitol. 1990;50:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barón SD, Morillas-Márquez F, Morales-Yuste M, Díaz-Sáez V, Gállego M, Molina R, Martín-Sánchez J. Predicting the risk of an endemic focus of Leishmania tropica becoming established in south-western Europe through the presence of its main vector, Phlebotomus sergenti Parrot, 1917. Parasitology. 2013;140:1413–1421. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013000942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boussaa S, Neffa M, Pesson B, Boumezzough A. Phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of southern Morocco: results of entomological surveys along the Marrakech- Ouarzazat and Marrakech-Azilal roads. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2010;104:163–170. doi: 10.1179/136485910X12607012374235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexander B, Maroli M. Control of phlebotomine sandflies. Med Vet Entomol. 2003;17:1–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2003.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belen A, Alten B, Aytekin AM. Altitudinal variation in morphometric and molecular characteristics of Phlebotomus papatasi populations. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:343–350. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Colmenares M, Portús M, Botet J, Dobaño C, Gállego M, Wolff M, Seguí G. Identification of blood meals of Phlebotomus perniciosus (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Spain by a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay biotin/avidin method. J Med Entomol. 1995;32:229–233. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/32.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossi E, Bongiorno G, Ciolli E, Di Muccio T, Scalone A, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Maroli M. Seasonal phenology, host-blood feeding preferences and natural Leishmania infection of Phlebotomus perniciosus (Diptera, Psychodidae) in a high-endemic focus of canine leishmaniasis in Rome province, Italy. Acta Trop. 2008;105:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Branco S, Alves-Pires C, Maia C, Cortes S, Cristovão JMS, Gonçalves L, Campino L, Afonso MO. Entomological and ecological studies in a new potential zoonotic leishmaniasis focus in Torres Novas municipality, Central Region, Portugal. Acta Trop. 2013;125:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiménez M, González E, Martín-Martín I, Hernández S, Molina R. Could wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) be reservoirs for Leishmania infantum in the focus of Madrid, Spain? Vet Parasitol. 2014;202:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aspöck H, Gerersdorfer T, Formayer H, Walochnik J. Sand flies and sandfly-borne infections of humans in Central Europe in the light of climate change. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120:24–29. doi: 10.1007/s00508-008-1072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poeppl W, Herkner H, Tobudic S, Faas A, Auer H, Mooseder G, Burgmann H, Walochnik J. Seroprevalence and asymptomatic carriage of Leishmania spp. in Austria, a non-endemic European country. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:572–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rioux JA, Houin H, Ranque J, Lapierre J. Écologie des Leishmanioses. Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1974. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; 1977. p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haeberlein S, Fischer D, Thomas SM, Schleicher U, Beierkuhnlein C, Bogdan C. First Assessment for the Presence of Phlebotomine Vectors in Bavaria, Southern Germany, by Combined Distribution Modeling and Field Surveys. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poeppl W, Obwaller AG, Weiler M, Burgmann H, Mooseder G, Lorentz S, Rauchenwald F, Aspöck H, Walochnik J, Naucke TJ. Emergence of sandflies (Phlebotominae) in Austria, a Central European country. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:4231–4237. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3615-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]