Abstract

Objective:

In this study, we aimed to investigate smoking prevalence and the degree of nicotine dependence in our hospital healthcare workers.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted between January 2008 and June 2008 in our hospital (Medical Facility of Atatürk University). A total of 691 (370 females, 321 males) subjects were included in this study. A questionnaire, including demographic findings, tobacco consumption information and the Fagerström nicotine dependence test, was distributed to healthcare workers and collected.

Results:

The questionnaire was answered by 691 health workers, 46.5% of whom were male, and 53.5% of whom were female. Overall, the rate of smoking was 36.9%; 48% of males and 27.6% of females were current smokers. When classified according to clinic, the greatest rate of smoking was in the psychiatry clinic (60.0%), and the lowest rate of smoking was in the ear, nose and throat (ENT) Clinic (0.0%). Thirty-four percent of nurses, 18.7% of doctors, 45.5% of officers, and 50.4% of ancillary staff were smokers. According to education level, 50% of the cases (smokers) graduated from primary school, 45% of the cases graduated from high school and 26.9% of the cases graduated from university. The major reason for the initiation of smoking was attention-seeking behavior. The age at smoking initiation was 7 to 20 years in 83.9% of cases and 21 to 35 years in the remaining 16.1%. Thirty-five percent of smokers had very low levels of dependence, while 11.9% had very high levels dependence. Ninety-two percent of cases indicated they would prefer to work at a smoke-free hospital. Ninety-five percent of cases would support making this facility a smoke-free hospital.

Conclusion:

The smoking rate was 36.9% amongst our hospital health workers. Smoking prevalence was higher in males (48%) than females (27.6%). The greatest smoking rate was amongst ancillary staff. Ninety-five percent of healthcare workers were supportive of a law requiring hospitals to be smoke-free.

Keywords: Healthcare workers, Medical facility, Smoking

Özet

Amaç:

Bu çalışmada hastanemiz çalışanları arasında sigara içme oranını ve içenlerde bağımlılık düzeyini saptamayı amaçladık.

Gereç ve Yöntem:

Çalışma, Ocak 2008 ile Haziran 2008 tarihleri arasında Tıp Fakültesi Araştırma Hastanesi’nde yürütüldü. Çalışmaya 691 (370 K, 321 E) olgu dahil edildi. Olgulara demografik bulgular, sigara içme düzeyi, Fagörstream bağımlılık testi içeren anket uygulandı.

Bulgular:

Çalışmaya katılan 691 olgunun %46.5’i erkek (321), %53.5’i da kadın (370) idi. Sigara içme oranı %36.9 olup, erkeklerin %48’i, kadınların %27.6’sı sigara içiyordu (p=0.000). Çalıştıkları bölüme göre sorgulandığında en yüksek sigara içme oranı psikiyatri kliniğinde %60.0, en düşük sigara içme oranı KBB kliniğinde %0.0 olarak bulundu. Hemşirelerin %34’ü, doktorların %18.7’si, memurların % 45.5’i, yardımcı personelin %50.4’ ü sigara içiyordu (p=0.000). Çalışmaya katılan ilk-orta öğretim mezunlarının %65.8’i, lise mezunlarının %45.1’i, üniversite mezunlarının ise %26.9’u sigara içiyordu. Sigaraya başlama nedeni %30’unda özenti ile ilk sırayı alıyordu. Sigaraya başlama yaşı %83.9’unda 7–20, %16.1’inde de 21–35 idi. Sigara içenlerin %34.5’i çok düşük düzeyde bağımlı, %28,4’ü düşük düzeyde bağımlı, %8.8’i orta düzeyde bağımlı, %16.5‘i yüksek düzeyde bağımlı, %11.9’u da çok yüksek düzeyde bağımlı idi. Sigara içenlerin %86.1’i sigarayı bırakmak istiyordu. Çalışmaya katılanların %92.8’i sigara içilmeyen bir hastanede çalışmak istiyordu. Olguların %95.1’i sigarasız hastane oluşturulmasına destek veriyordu.

Sonuç:

Hastane çalışanlarında sigara içme oranı %36.9 bulundu. Erkeklerde bu oran %48 olup, bayanlara göre daha yüksekti. Meslek grupları dikkate alındığında en yüksek sigara içme oranı yardımcı personel grubunda saptandı. Hastane çalışanlarının %95’i sigara içilmeyen hastane yasasına destek veriyordu.

Introduction

Tobacco use is an important public health issue around the world, especially in developing countries. The World Health Organization has reported that 60 million people died between 1950 and 2000 due to smoking-related illnesses, more than the number of deaths in World War II [1,2]. A mortality study by Peto et al. showed that smoking has decreased life expectancy by 16 years in all age groups and by 22 years in the 35–69 age group [2]. Recent studies link smoking with an increased risk of diseases, such as coronary heart disease and cancers, as well as early death [2–7]. Half a billion people worldwide die due to cigarette use each year, and approximately half of those deaths are in the 35–69 age group [8]. The danger of tobacco smoke is not limited to the smoker; environmental tobacco smoke increases the risk of lung cancer to 30% for nonsmokers [9–13]. In the United States, each year, 3,000 lung cancer cases is are attributed to environmental tobacco smoke [13].

According to the National Institute of Statistics [14], in 1990, the most common cause of death in Turkey was cardiovascular disease, and the third cause of death was cancer. Lung cancer has become the leading cause of cancer deaths. The fourth leading cause is cerebrovascular disease, and the association of these diseases with smoking has been shown in various studies [10–15].

The smoking rate in Turkey is second in Europe following Greece. Unlike trends in developed countries, the smoking rate is increasing in Turkey [16–18]. Three principle aims have been identified to stop the harms caused by cigarettes. The first and most important aim is to prevent children and adolescents from ever starting to smoke. The second aim is to encourage smokers to quit, and the third aim is to protect others from the passive effects of smoking by reducing exposure to secondhand smoke [18].

Despite the perception of physicians as role models for teenagers and society as a whole, the smoking rate of physicians is greater than the average of the general population in Turkey [17]. Physicians and other healthcare workers have an increasingly important role to help reduce risk of tobacco-related health problems within their communities. If healthcare workers become actively involved in anti-smoking efforts, through their actions and words, they will further motivate those who seek their help to quit smoking.

In this study, we aimed to identify smoking rates and the level of nicotine addiction among hospital employees.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted between January 2008 and June 2008 in the Medical Facility of Atatürk University Research Hospital. 750 subjects were included in this study. 59 questionnaires were not completed or returned. There were 370 women and 321 men. We distributed a questionnaire with 27 questions, including demographic findings, tobacco consumption information and the Fagerström nicotine dependence test. SPSS 11 statistical software was used for analysis.

Results

In this study, 46.5% of 700 subjects were men (321) and 53.5% were women (370). Subjects were between 17 and 66 years old. The overall smoking rate was 36.9%; 48% of men and 27.6% of women were smokers (p=0.000). Twenty-seven percent of subjects were former smokers. When we examined smoking cessation behaviors, 70.6% of these subjects had quit completely at once (“cold turkey”), whereas 29.4% had gradually quit (tapering). Seven percent of subjects had received professional support while trying to quit.

When we classified smokers by hospital department, the highest smoking rate (60.0%) was in the psychiatric clinic, and the lowest smoking rate (0.00%) was in the ear, nose and throat (ENT) clinic. Interestingly, the smoking rate in the pulmonary disease clinic was 4.4%. The smoking rate of all clinics is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Smoking rates among healthcare workers according to department

| Departments | Smokers | Nonsmokers |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatry | 60.0% | 40.0% |

| Infectious Disease | 56.5% | 43.5% |

| General Surgery | 52.6% | 47.4% |

| Emergency Medicine | 55.6% | 44.4% |

| Cardiology | 50.0% | 50.0% |

| Pulmonology | 4.4% | 96.4% |

| Thoracic Surgery | 1.1% | 89.9% |

| Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) | 0.0% | 100% |

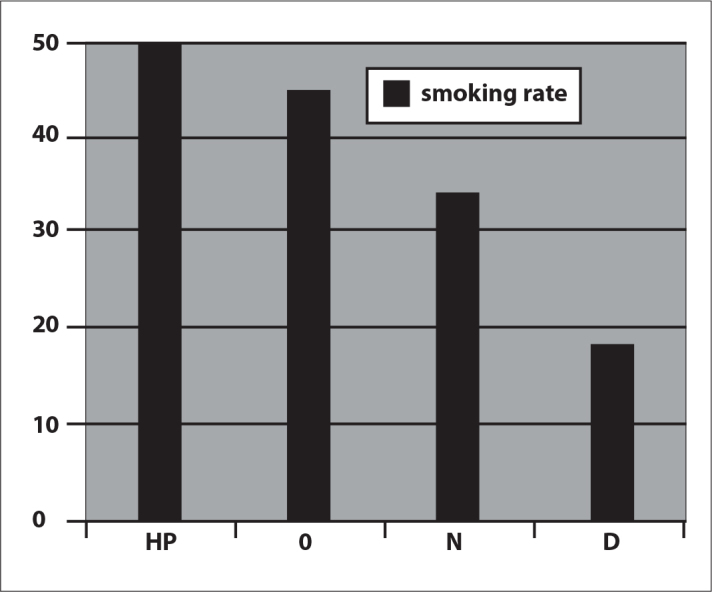

When we classified the subjects according to their occupation, 37.6% of subjects were nurses, 24.5% were doctors, 16% were officers, and 21.9% were ancillary staff. The highest smoking rate was amongst ancillary staff. Thirty-four percent of nurses, 18.7% of doctors, 45.5% of officers and 50.4% of ancillary staff were smokers (p=0.000). Classification of smoking rates according to occupation is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Classification of smoking rates according to occupation.

Looking at the level of education, 57.3% of subjects had graduated from university, and 4.3% had graduated from primary school. Sixty-five percent of first and secondary education graduates, 45.1% of high school graduates and 26.9% of university graduates were current smokers.

When we asked subjects why they started smoking, 30.8% of them said they wanted attention 19.4% cited stress and sadness, 19% were curious and 16.2% attributed their behavior to other reasons.

Eighty-four percent of subjects had started to smoke between the ages of 7 to 20, and 16.1% began to smoke between the ages of 21 to 35. The minimum age of male smokers was 17.6±2.3 years, the maximum age was 66±2.1 and the mean age was 33.68±3.54 years. The minimum age of female smokers was 18.1±3.6, the maximum age was 51±4.2, and the mean age was 30.46±3.64 years. Sixty percent of the smokers were married, and 40% were single.

Thirty-two percent of all smokers were smoking less than 10 cigarettes per day, 49.0% were smoking 11 to 20 cigarettes, 11.7% were smoking 21 to 30 cigarettes, and 7.7% were smoking 31 or more cigarettes in a day. When classified according to the dependence level, 34.5% of them had very low levels of dependence, 28.4% had low-level dependence, 8.8% had medium-level dependence, 16.5% had high-level dependence and 11.9% had very high-level dependence.

The most popular time for smoking the first cigarette was the first hour after waking up in the morning. Thirty-six percent of smokers were smoking their first cigarette within 1 hour of waking up, and 24.6% were smoking within the first 5 minutes. The most common cigarette that the smokers could not give up was the first cigarette of morning (47.7%).

Eighty-seven percent of the smokers were smoking until the end of a cigarette. Twenty-three percent enjoyed having a cigarette in their mouth, and 35.9% were enjoyed holding the cigarette in their hand. Sixty-eight percent of the smokers were deeply inhaling the cigarette smoke.

Eighty-six percent of the smokers wanted to give up smoking. The most common reason for wanting to quit was fear of illness (33.3%), but 64.2% of smokers who wanted to quit did not believe that they could do so successfully. When asked whether they would want to smoke if they were seriously ill, 76.4% of the smokers said no.

Ninety-three percent of the health workers surveyed wanted to work in a smoke-free hospital, while 7% of workers were opposed this idea. Ninety-five percent of subjects were willing to support development of a smoke-free hospital. This information was very important for future studies in our hospital.

Discussion

Cigarette smoking, one of the foremost causes of death in the world, is also one of the most easily preventable of all risk factors for disease. Tobacco dependence increases the risk of illnesses such as cancer, respiratory tract diseases, and cardiovascular diseases. Children who are exposed to cigarette smoke, especially those exposed during the prenatal period, are more likely to have respiratory tract diseases, cancers and other health problems [19].

According to a study conducted in 2003 among physician members of the Thoracic Society, 35% of physicians were smokers, which was less than the average for the general public and other physicians. These decreased smoking rates were attributed to the qualifications of the group involved in the study who were mostly pulmonary disease specialists or residents [19].

Various studies conducted in our country detected smoking rates among physicians from 41.3% to 54%. This rate was similar to that of developing countries, while smoking rates among physicians in developed countries are lower or decreasing. Smoking rates among physicians dropped from 18.8% to 3.3% in the United States and from 29% to 18% in Germany from 1974 to 1991, and the downward trend in these countries continues [19, 20].

In a study of Israeli physicians, smoking rate was 15.8%. The rate varied according to specialty. For example, 40% of radiologists, 25% of surgeons and anesthesiologists, and 8% of internists and pediatricians were cigarette smokers [20]. According to another study of Israeli doctors, 54% of physicians were heavy smokers [19, 20]. In our study, the overall rate of smoking in our hospital was 36.9%, and 18.7% of physicians were smokers. We found that the smoking rate among our physicians was similar to rates among physicians in developed countries. Our results were low compared to other studies conducted in our country. As a result, we believe there is a need for national studies of smoking bans in closed areas.

In a study conducted in 2004 at Dr. Suat Seren Chest Diseases and Chest Surgery Research Hospital, the prevalence of cigarette smoking seemed to be higher among healthcare workers compared to the community. According to the study, the average age at first cigarette use was 17.7±4.3 for males and 19.5±3.9 for females [20]. In another study conducted in 1996 on healthcare workers at Pamukkale University, 48% of the workers were current smokers, and the mean age of smokers was 27.5 years [21]. The study conducted by Salepci et al. clarified that cigarette use was 36.9% among hospital workers[22]. Another study at Alman Hospital showed that 39.8% of workers surveyed were smokers, and the age at first cigarette use was 18 to 25 years for 28.6% of these smokers [23]. In our study, cigarette use was 36.9% among healthcare workers, and the minimum age of starting to smoke was 17.6±2.3 for men and 18.1±3.6 for women.

In a survey of health workers at Karaelmas University in 2004 [24], the smoking rates for males and females were 47.6% and 25.7%, respectively. The highest rate of smoking was among the ancillary staff (62.9%), which was attributed to their considerably low income. The rate of cigarette smoking among physicians was 45.2%. More than half of the cases in all groups had tried to stop smoking.

In this study, 41.3% of the health workers at the medical facility and hospital were smokers. Studies conducted in Turkey have determined that smoking is more common among males than females, a fact that is attributed to socioeconomic conditions. In our study, 36.9% of healthcare workers were smokers, and the highest rate of smoking among health workers was in the group of ancillary staff (50.4%). The rate of cigarette smoking among physicians was 18.7%, and the smoking rates for males and females were 48.0% and 27.6%, respectively.

Among factors considered as primary reasons for initial cigarette use are curiosity and attention. For healthcare workers involved in the study of Karaelmas University, this finding was true [24]. The study of workers at Alman Hospital showed that friends were the most common reason to start using cigarettes [23]. In our study, the most common reason to start smoking was to gain attention.

Approximately half of the adult population in Turkey smokes cigarettes. In our country, 17 million smokers spend 40 million USD each day and 15 billion USD each year. In Turkey, about 100,000 smokers die from cigarette-related diseases every year. The economic damage to the country because of cigarette-related diseases is 2.72 billion USD per year. Workforce losses have not been included in this value. This economic loss impacts even developed countries whose annual earning is ten times bigger than ours. Therefore, developing countries, such as Turkey which has a high burden of debt, must take serious strides toward prevention, and national tobacco control must become a government priority.

It has been suggested that physicians and other health workers play an important role in the war against cigarettes. However, the fact that physicians and other healthcare personnel smoke around both patients and family members leads to negative perceptions and can undermine the war against cigarette smoking.

Conclusions

Consequently, physicians and other healthcare workers must bear the greatest responsibility in the war against smoking despite high rates of cigarette smoking among these professionals. Hospital administrators must also inform their personnel about effective programs for smoking cessation and provide continuing education programs relating to their roles as important influences in society. Considering smoking rates among health workers, awareness about the risk of cigarettes, especially for employees other than physicians, must be raised, and more precautions against cigarette smoking must be developed. By cooperating with the leadership in our foundation and working together with other departments, our personnel must be educated and encouraged to stop smoking for the benefit of their own health and that of the general public.

Footnotes

Summary of this manuscript presented in: Leyla Sağlam, Esra Kadıoğlu,Ravza Bayraktar, Hamit Acemoğlu. Atatürk Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Çalışanlarında Sigara İçme Oranı ve Bağımlılık Düzeyi Belirlenmesi. TÜSAD 30.Ulusal Kongre, (2008) PS-134

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Guidelines for the Conduct of Tobacco Smoking Surveys Among General Population WHO-SMO. 1983;83:4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C., Jr . Mortality from Smoking In Developed Countries 1950–2000. 1st Edn. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1994. pp. 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ha BM, Yoon SJ, Lee HY, et al. Measuring the burden of premature death due to smoking in Korea from 1990 to 1999. Public Health. 2003;117:358–65. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, et al. Relationship between peridondal disease, tooth loss, and carotid artery plaque. The oral infections and vascular disease epidemiology study (INVEST) Stroke. 2003;34:2120–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000085086.50957.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Jiao L. Molecular epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2003;33:3–14. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:33:1:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khot UN, Khot MB, Bajzer CT, et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2003;290:898–904. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruano-Ravina A, Figueriras A, Montes-MartÃnez A, et al. Dose-response relationship between tobacco and lung cancer: new findings. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:257–63. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyer D. The Tobacco Referrence Guide. Published on UICC GLOBALink. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izumi Y, Tsuji I, Ohkubo T, et al. Impact of smoking habit on medical care use and its costs: a prospective observation of National Health Insurance beneficiaries in Japan. Int J of Epidemiol. 2001;30:616–21. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tobacco or Health Smoke-Free Europe: 4 WHO Regional Office for Europe, the International Agency for Research on Cancer and Commission of the European Communities. 1988. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph.../life_style/Tobacco/.../tobacco_exs_en.pdf. Date last updated Jan 03, 2002. Date last accesed May 03, 2010.

- 11.Stoddard JJ, Gray B. Maternal Smoking and Medical Expenditures for Childhood Respiratory Illness. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:205–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connell EJ. Pediatric allergy; a brief review of risk factors associated with developing allergic disease in childhood. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:53–8. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A Statement of the Joint Committee on Smoking and Health: Smoking and Health: Physician Responsibility. Special Report. Chest. 1995;108:1118–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mortality İstatistics . T.C. BaşbakanlıkDevlet İstatistik Enstitüsü; Ankara: 1990. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grundy SM, Balady GJ, Criqui MH, et al. Primary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease: Guidance From Framingham. A statement for Healthcare Professionals From the AHA Task Force on Risk Reduction. Circulation. 1998;97:1876–87. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crofton ST. Tobacco and the third World, no tobacco. Thorax. 1990;45:164–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.3.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turkish Health Ministry . Smoking habits and attitudes of Turkish population towards smoking and antismoking campaigns. Turkey: Turkish Health Ministry, PIAR; Jan, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bilir N. Where We Are in The Fight Against. Smoking? (Sigara İle Savaşın Neresindeyiz?) Hacettepe Medical Bulletın. 1997;28:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosku N, Kosku M, Cıkrıkcıoğlu U, et al. Smoking Habits and Attitudes of the Members of the Thoracic Society. 2003;4:223–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erbaycu AE, Aksel N, Cakan A, et al. Smoking Habit of Health Professionals in İzmir City. 2004;5:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozkurt S, Bostancı M, Altın R, Ozşahin A, Akdag B. Prevalance of Smoking, Nicotine Addiction and Pulmonary Function Tests in Workers of Faculty of Medicine. Tuberk Toraks. 2000;48:140–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salepci B, Fidan A, Oruç O, et al. Success Rates in Our Smoking Cessation Clinic and Factors Affecting It. Toraks Dergisi. 2005;6:151–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atılgan Y, Gurkan S, Sen E. Smoking Habits of the Personnel Employed in Our Hospital and the Factors Affecting the Same. 2008;9:160–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altın R, Kart L, Unalacak M, et al. Evaluation of Cigarette Smoking Prevalence and Behaviors in Medical Faculty Hospital Personnel, The Medical Journal of Kocatepe. 2004;5:63–7. [Google Scholar]