Abstract

Objective:

Whether drains should be routinely used after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is still debated. We aimed to retrospectively evaluate the benefits of drain use after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for non-acute and non-inflamed gallbladders.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred and fifty patients (mean age, 47±13.8 years; 200 females and 50 males) who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholestasis were included in the study. The medical files of the patients were examined retrospectively to obtain data on patient demographics, cholecystitis attacks, complications during the operation, whether a drain was placed in the biliary tract during the operation, etc. The volume of the fluid collection detected in the subhepatic area by ultrasonography on the first postoperative day was recorded.

Results:

Drains were placed in 51 patients (20.4%). The mean duration of drain placement was 3.1±1.9 (range 1–16) days. Fluid collection was detected in the gallbladder area in 67 patients (26.8%). The mean volume of collected fluid was 8.8±5.2 mL. There were no significant effects of age, gender, and previous cholecystitis attacks on the presence or volume of the fluid collection (P>0.05 for all). With regard to the relationship between fluid collection and drains, 52 of 199 (26.1%) patients without drains had postoperative fluid collection, compared to 15 of 51 (29.4%) patients with drains (P>0.05).

Conclusion:

In conclusion, there is no relationship between the presence of a drain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the presence of postoperative fluid collection. Thus, in patients without complications, it is not necessary to place a drain to prevent fluid collection.

Keywords: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, drains, ultrasonography

Özet

Amaç:

Laparoskopik kolesistektomi sonrası rutin olarak dren kullanımı hala üzerinde tartışılan bir konudur. Bu çalışmada akut olmayan noninflamatuar safra kesesi için uygulanan laparoskopik kolesistektomi sonrası dren kullanımının avantajlarını retrospektif olarak değerlendirmeyi amaçladık.

Gereç ve Yöntem:

Çalışmaya kolestaz nedeniyle laparoskopik kolesistektomi uygulanan 250 hasta (ortalama yaş, 47±13.8 yıl; 200 kadın ve 50 erkek) dahil edildi. Hasta dosyaları retrospektif olarak değerlendirilerek demografi, kolesistit atak, cerrahi komplikasyonlar, cerrahi sırasında biliar trakt üzerine dren yerleştirilme durumu v.b. üzerine veri toplandı. Postoperatif ilk gün ultrasonografide subhepatik alanda biriken sıvı hacmi kaydedildi.

Bulgular:

Hastaların 51’ine (%20.4) dren yerleştirildi. Ortalama dren kalış süresi 3.1±1.9 gün (aralık, 1–16 gün) idi. Altmış yedi (%26.8) hastada safra kesesi bölgesinde sıvı birikimi görüldü. Ortalama sıvı hacmi 8.8±5.2 mL idi. Sıvı birikimi varlığı ve hacmi üzerinde yaşın, cinsiyetin ve önceki kolesistit ataklarının etkisi yoktu (tümü için P>0.05). Sıvı birikimi ve dren arasındaki ilişki değerlendirildiğinde, dren takılmayan 199 hastanın 52’sinde (%26.1) ve dren olan 51 hastanın 15’inde (%29.4) sıvı birikimi olduğu görüldü (P>0.05).

Sonuç:

Laparoskopik kolesistektomide dren varlığı ile postoperatif sıvı birikimi arasında ilişki yoktur. Bu nedenle komplikasyonsuz hastalarda sıvı birikimini önlemek için dren kullanımına gerek yoktur.

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is an increasingly accepted technique worldwide for the treatment of cholestasis. This technique has the advantages of a shorter hospital stay, an earlier return to normal activity, better cosmetic results, and lower rates of postoperative pain and complications than other techniques. Despite being a less invasive technique, some patients complain of postoperative shoulder pain, nausea, and vomiting [1, 2]. Some publications recommend the use of a short-term drain postoperatively based on the theory that high-pressure CO2 insufflation during the operation and the accumulation of gas in the right subphrenic area leads to these complaints [2–4]. Routine drain use after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is still debatable. The main indication for drain use after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is to prevent a biloma or hematoma. According to the Cochrane Database Systemic Review, randomized clinical studies show no benefit of a drain [5]. Some studies even claim that drains are harmful [6]. The tendency of surgeons to use or not use drains seems to be a matter of habit and experience.

We aimed to evaluate the benefits of drain use after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for non-acute and non-inflamed gallbladders.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This was a retrospective study that enrolled patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholestasis and who did not have cholecystitis, cholangitis, or pancreatitis during the operation, did not have contraindications to a laparoscopic approach, and who did not require a biliary tract intervention. Patients who had operations postponed because of acute cholecystitis or similar reasons and had a cholecystectomy later were included in the study. Patients who had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy converted to an open cholecystectomy for any reason or those who did not undergo ultrasonographic evaluation on the first postoperative day were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design of the study.

Surgical procedures

The procedures were performed by the same team at Ataturk Training and Investigation Hospital, First General Surgery Clinic between 2008 and 2012; all of the surgeons had performed at least 50 laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedures. Under general anesthesia, an incision was made below the umbilicus, and a 10-mm trocar was inserted for CO2 insufflation. Subsequently, other trocars were placed through subxiphoid, subcostal-midclavicular and subcostal-anterior-axillary incisions. The pneumoperitoneum pressure was set at 14 mmHg, and the CO2 flow was set at 2 L/min.

Data collection

The medical files of the patients were examined retrospectively to obtain data on patient age and gender, history of cholecystitis attacks, complications during the operation (bleeding, gallbladder perforation, etc.), whether a drain was placed in the biliary tree during the operation, duration of any drains used, and duration of hospitalization. The volume of fluid collection detected in the subhepatic area on ultrasonography on the first postoperative day was recorded. In patients who had fluid collections, the collection was reassessed by ultrasonography 30 days postoperatively. For analysis, the volume of fluid was stratified into <5, 6–10, and >10 mL groups.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, the computer software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 11.5, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were utilized to determine the distributions within groups. When comparing normally distributed groups, the chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used. Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean values of groups. A P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics

In total, 250 patients were included in the study. Their mean age was 47±13.8 years; 200 were female and 50 were male (Table 1). Seventy of the patients (28%) had a history of cholecystitis. Complications developed in six patients during the operation: bleeding in four and gallbladder perforation in two. Drains were placed in 51 patients (20.4%). The mean duration of drain placement was 3.1±1.9 (range 1–16) days. The mean duration of hospitalization was 4±2.9 days in patients with drains and 2.9±1.5 days in patients without drains. The presence of a drain prolonged the duration of hospitalization considerably.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study patients (n=250)

| Mean±SD or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47±13.8 |

| Gender (female/male) | 250/50 |

| Previous acute cholecystitis attacks | 7 (28%) |

| Drain placement | |

| Yes | 51 (20.4%) |

| No | 199 (79.6%) |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | |

| Drain (+) | 4±2.9 |

| Drain (−) | 2.9±1.5 |

SD: standard deviation.

Postoperative fluid collection

On hepatobiliary ultrasonography performed on the first postoperative day, a fluid collection was detected in the gallbladder fossa in 67 patients (26.8%). The mean volume of collected fluid was 8.8±5.2 mL. The fluid collection was <5 mL in 46 patients, 6–10 mL in 8 patients, and >10 mL in 13 patients. There were no significant effects of age, gender, and a history of previous cholecystitis attacks on the presence of a fluid collection. A postoperative fluid collection was recorded in 14 (28%) male patients and 53 (26.5%) female patients (P>0.05). The patients were stratified into 10-year age groups; no significant relationship was found between age and the presence of a postoperative fluid collection (P>0.05). A fluid collection was present in 28.6% of the patients with a history of acute cholecystitis and 26.1% of the patients without a history of acute cholecystitis (P>0.05).

Of the six patients who had complications during their operation, four had no fluid while two had fluid collections of 5–100 mL on the first postoperative day. Although the number of patients was small, there was no significant relationship between the occurrence of complications and the presence of a postoperative fluid collection.

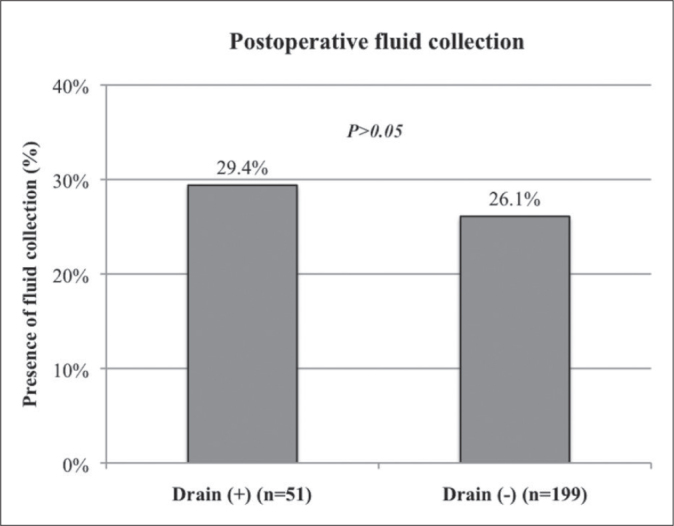

With regard to the relationship between a fluid collection and drains, 52 of 199 (26.1%) patients without drains had fluid collections, compared to 15 of 51 (29.4%) patients with drains (Figure 1). The difference in the volume of fluid between the groups with and without drains was not significant. Of the patients with a fluid collection that was detected on the first postoperative day, only two still had fluid collections on repeat ultrasonography at 30 days, but their volumes were <5 mL. The fluid volumes in these patients on the first postoperative day were 19 and 9 mL.

Figure 1.

The effect of drain placement on the presence of a postoperative fluid collection.

Discussion

Thirty-one years after Langenbuch performed the first cholecystectomy in 1919 [7], a cholecystectomy performed without drains was called the “ideal technique” in Germany [8]. Although many subsequent studies support this statement, the use of drains following cholecystectomy remains controversial [9–12]. Although there is no supporting scientific evidence, it would not be a mistake to call the routine use of drains after abdominal operations a traditional practice. In view of the higher probability of preventing surgical complications, such as leaks and bleeding or of early detection with a drain, the frequency of drain use can be better understood. Other studies claim that closed drainage systems are not useful after abdominal operations, such as cholecystectomy [13], colorectal resection [14], and pancreatic resection [15] and suggest that drain use increases the likelihood of intra-abdominal and wound site infections and hence the duration of hospitalization with worsening lung function [13,16].

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy may be regarded as a standard operating technique because of quicker healing of cholestasis, lower rates of wound site and intra-abdominal infection, and shorter hospital stays. However, complaints such as postoperative shoulder pain, back pain, vomiting, and nausea related to pneumoperitoneum can occur after laparoscopy [1, 2]. In some studies of pneumoperitoneum, such complaints were more common in the high-pressure group than the normal-pressure group [17, 18].

The real reason for placing a drain in the subhepatic area after cholecystectomy is the fear of biliary leakage or bleeding, which can lead to peritonitis. This makes drain use a more effective option in the presence of an aberrant biliary tract, suspicion of clipping the cystic canal, or when dissection is difficult enough to cause bleeding.

Myers described ‘drain fever syndrome’ after cholecystectomy in 1962 [4, 16]. In this condition, fever and right upper quadrant pain develop if a drain is in place for longer than 48 hours. The pain and fever disappeared spontaneously within 1–3 days and occurred in 23% of the group with drains and 4% in the group without drains [19]. This difference may be explained as follows: 1) the presence of a drain causes a foreign body reaction [20, 21]; 2) the drain forms a connection between the peritoneal cavity and skin [22]; and 3) the feeling of discomfort produced by the drain prevents patients from coughing [12]. Similarly, Cruse and Foord established that wound site infection was five times more common in the group with drains than in the group without drains [23].

In our study, 67 of 250 (26.8%) patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy experienced fluid collection in the subhepatic area on hepatobiliary ultrasound (US) carried out on the first postoperative day. In a study of 130 patients, Kong et al. reported a postoperative subhepatic fluid collection in 25.5% of patients after conventional cholecystectomy [24]. The results of these two studies imply that the rate is independent of whether cholecystectomy is carried out conventionally or laparoscopically.

In conclusion, there is no relationship between the presence of a drain in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and postoperative fluid collection. We suggest that, in patients without complications, it is not necessary to place a drain to prevent fluid collection. In patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and in whom a subhepatic fluid collection is suspected, when an ultrasonography evaluation is conducted during the early postoperative period, ultrasonographic follow-up is required only if the volume is >10 mL.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Sarli L, Costi R, Sansebastiano G, Trivelli M, Roncoroni L. Prospective randomized trial of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum for reduction of shoulder-tip pain following laparoscopy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1161–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniades J, Sagkana E. Randomized comparison between different insufflation pressures for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:245–9. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vezakis A, Davides D, Gibson JS, et al. Randomized comparison between lowpressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy and gasless laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:890–3. doi: 10.1007/s004649901127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott J, Hawe J, Srivastava P, Hunter D, Garry R. Intraperitoneal gas drain to reduce pain after laparoscopy: randomized masked trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurusamy KS, Samraj K, Mullerat P, Davidson BR. Routine abdominal drainage for uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD006004. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006004.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monson JR, Guillou PJ, Keane FB, Tanner WA, Brennan TG. Cholecystectomy is safer without drainage: the results of a prospective, randomised clinical trial. Surgery. 1991;109:740–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langenbuch C. Ein fall con Extirpation der Gallenblase wegen Chronischer Cholelithiasis. Heilung Berl Klin Wochenschr. 1882;19:725–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kole W. Erfaungen mit der Drainagelosen, idealen Cholecystektomie. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1969;324:307–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01238558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verbrycke JR. Cholecystectomy without drainage: report of eighty-six cases without mortality. Med J Rec. 1927;126:705–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler RS. Cholecystectomy without drains. Ann Surg. 1931;93:745–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193103000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreese WC. Cholecystectomy without drainage. J Int Coll Surg. 1963;40:433–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kambouris AA, Carpenter MS, Allaben RD. Cholecystectomy without drainage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1973;137:613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ammori BJ, Davides D, Vezakis A, et al. Day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation of a 6-year experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:303–8. doi: 10.1007/s00534-002-0807-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh CY, Changchien CR, Wang JY, et al. Pelvic drainage and other risk factors for leakage after elective anterior resection in rectal cancer patients: a prospective study of 978 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:9–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000150067.99651.6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conlon KC, Labow D, Leung D, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial of the value of intraperitoneal drainage after pancreatic resection. Ann Surg. 2001;234:487–93. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Abdominal drainage after hepatic resection is contraindicated in patients with chronic liver diseases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:194–201. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109153.71725.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wills VL, Hunt DR. Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:273–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barczynski M, Herman RM. A prospective randomized trial on comparison of low-pressure (LP) and standard-pressure (SP) pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:533–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers MB. Drain fever: a complication of drainage after cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1962;52:314–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glenn F. Trends in surgical treatment, of calculous disease of the biliary tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:877–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds JT. Intraperitoneal drainage: when and how? Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1955;101:242–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nora PF, Vanecko RM, Brasfield JJ. Prophylactic abdominal drains. Arch Surg. 1972;105:173–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180080027005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five year prospective study of 23.649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107:206–10. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1973.01350200078018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KS, Sohn SK, Lee HD, Kim MW, Kim SJ. Results of subhepatic fluid collection after cholecystectomy; a serial sonographic study. Yonsei Med J. 1987;28:139–42. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1987.28.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]