Abstract

Background

The frequency of gender identity disorder is hard to determine; the number of gender reassignment operations and of court proceedings in accordance with the German Law on Transsexuality almost certainly do not fully reflect the underlying reality. There have been only a few studies on patient satisfaction with male-to-female gender reassignment surgery.

Methods

254 consecutive patients who had undergone male-to-female gender reassignment surgery at Essen University Hospital’s Department of Urology retrospectively filled out a questionnaire about their subjective postoperative satisfaction.

Results

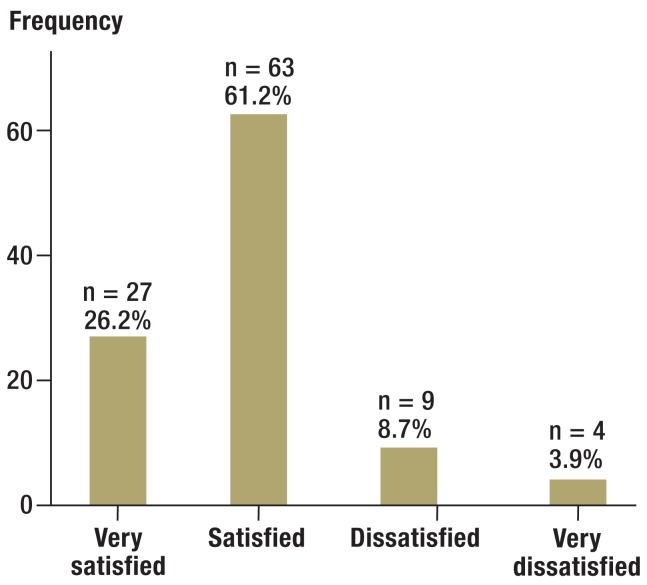

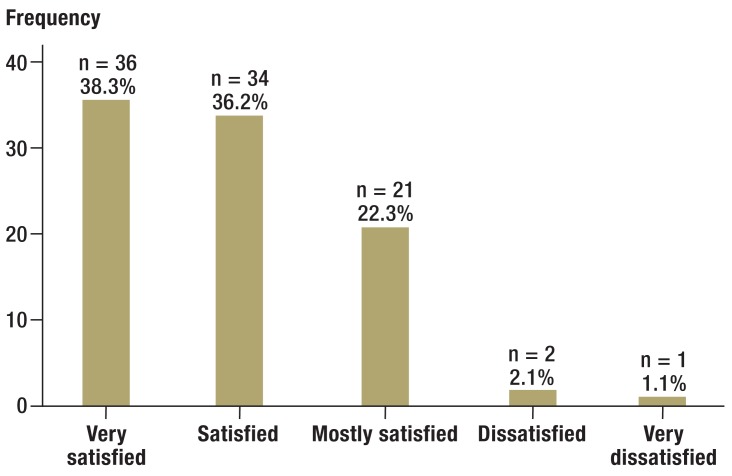

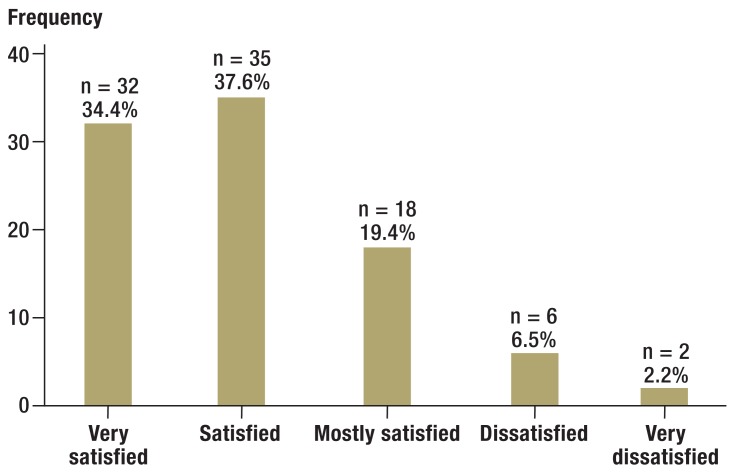

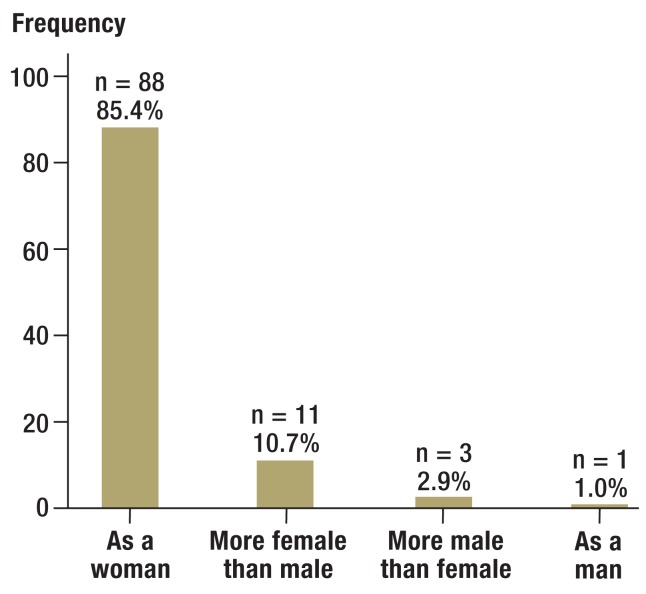

119 (46.9%) of the patients filled out and returned the questionnaires, at a mean of 5.05 years after surgery (standard deviation 1.61 years, range 1–7 years). 90.2% said their expectations for life as a woman were fulfilled postoperatively. 85.4% saw themselves as women. 61.2% were satisfied, and 26.2% very satisfied, with their outward appearance as a woman; 37.6% were satisfied, and 34.4% very satisfied, with the functional outcome. 65.7% said they were satisfied with their life as it is now.

Conclusion

The very high rates of subjective satisfaction and the surgical outcomes indicate that gender reassignment surgery is beneficial. These findings must be interpreted with caution, however, because fewer than half of the questionnaires were returned.

Culturally, gender is considered an obvious, unambiguous dichotomy. The term “gender identity” denotes the consistency of one’s emotional and cognitive experience of one’s own gender and the objective manifestations of a particular gender. In gender identity disorder, one’s own anatomical sex is objectively perceived but is felt to be alien, whereas the term “gender incongruence” refers to a difference between an individual’s gender identity and prevailing cultural norms. Finally, gender dysphoria is the suffering that results. The treatment guidelines of the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) state that gender identity need not coincide with anatomical sex as determined at birth. Transgender identity should therefore be considered neither negative nor pathological (1). Unfortunately, gender incongruence often leads to discrimination against the affected individual, which can favor the development of psychological complaints such as anxiety disorders and depression (2– 4). While some transgender individuals are able to realize their gender identity without surgery, for many gender reassignment surgery is an essential, medically necessary step in the treatment of their gender dysphoria (5). Research conducted to date has shown that gender reassignment surgery has a positive effect on subjective wellbeing and sexual function (2, 6, 7). The surgical procedure (penile inversion with sensitive clitoroplasty) is described in eBox 1.

eBox 1. Surgical procedure for penile inversion vaginoplasty.

Open the scrotum.

Remove both testicles, including the spermatic cord, from the superficial inguinal ring.

Make a circular cut around the skin of the shaft of the penis under the glans and prepare the skin of the shaft of the penis as far as the base of the penis.

Separate the urethra from the erectile tissue.

Separate the neurovascular bundle from the erectile tissue.

Perform bilateral resection of the erectile tissue.

Create a space for the neovagina between the rectum and urethra or prostate (the prostate is left intact).

Invert the skin of the shaft of the penis and close the distal end.

Insert a placeholder into the neovagina (= the inverted skin of the shaft of the penis).

Create passages for the neoclitoris (former glans penis) and urethra and then fix in place.

Inject fibrin glue into the neovagina.

Position the neovagina, including the placeholder.

Adjust the labia majora.

During a second operation six to eight weeks after the first, the vaginal entrance is constructed and minor plastic corrections are made if necessary.

Surgery lasts an average of approximately 3.5 hours. Preservation of the neurovascular bundle results in a sensitive clitoroplasty. The most common complications in short-term postoperative recovery include superficial wound healing problems around the external sutures. In the medium and long term there is a risk of loss of depth (23, 24, 30, e15, e23, e25) or breadth (24, 30, e11, e19, e25) of the neovagina in particular. These problems usually result from inconsistent dilatation (e27).

Prevalence

No official figures are available on the prevalence of transgender or gender-nonconforming individuals, and it is very difficult to arrive at a realistic estimate. There is no central reporting register in Germany. Furthermore, figures for those who seek medical help for gender dysphoria would in any case give only an imprecise idea of the true prevalence. The global prevalence of transgender individuals has been estimated at approximately 1 per 11 900 to 1 per 45 000 for male-to-female individuals and approximately 1 per 30 400 to 1 per 200 000 for female-to-male individuals (1). Weitze and Osburg estimate prevalence in Germany at 1 per 42 000 (8). In contrast, De Cuypere et al. (9) suppose a prevalence of 1 per 12 900 for Belgium. Biosnich et al. (10) estimate prevalence among US veterans at 1 per 4366. This compares to an estimated prevalence of 1 per 23 255 in the general population. Even if percentages of transgender individuals in different parts of the world are comparable, it is highly likely that cultural differences will lead to differing behavior and expression of gender identity, resulting in differing levels of gender dysphoria (1). The ratio of male-to-female to female-to-male transgender individuals varies greatly. Although it was given as approximately 3:1 by van Kesteren (11), it is 2.3:1 according to Weitze and Osburg (8) and 1.4:1 according to Dhejne (3). Garrels (12) found a gradual decrease in the difference between the two figures in Germany, with the ratio decreasing from 3.5:1 (in the 1950s and 60s) to 1.2:1 (1995 to 1998) (Table 1).

Table 1. Prevalence of transsexualism and ratio of male-to-female to female-to-male cases (by year of publication).

| Author | Year | Country | MTF | FTM | MTF:FTM ratio (rounded) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (per 100000) | |||||

| Pauly (31) | 1968 | USA | 1.0 | 0.25 | 4:1 |

| Walinder (32) | 1968 | Sweden | 2.7 | 1.0 | 3:1 |

| Hoenig and Kenna (33) | 1974 | UK | 3.0 | 0.93 | 3:1 |

| Ross et al. (34) | 1981 | Australia | 4.2 | 0.67 | 6:1 |

| O’Gorman (35) | 1982 | Ireland | 1.9 | – | 3:1 |

| Tsoi (36) | 1988 | Singapore | 35.1 | 12.0 | 3:1 |

| Ekland et al. (37) | 1988 | Netherlands | 18 | 54 | 3:1 |

| van Kesteren et al. (11) | 1996 | Netherlands | 8.8 | 3.2 | 3:1 |

| Landén et al. (38) | 1996 | Sweden | – | – | 3:1 |

| Weitze and Osburg (8) | 1996 | Germany | 2.4 | 1.0 | 2:1 |

| Wilson et al. (39) | 1999 | Scotland | 13.4 | 3.2 | 4:1 |

| Garrels et al. (12) | 2000 | Germany | – | – | 1:1 |

| Haraldsen and Dahl (40) | 2000 | Norway | – | – | 1:1 |

| Olsson and Moller (e1) | 2003 | Sweden | – | – | 2:1 |

| Gomez-Gil et al. (e2) | 2006 | Spain | 4.7 | 2.1 | 2:1 |

| de Cuypere et al. (9) | 2007 | Belgium | 7.7 | 3.0 | 3:1 |

| Vujovic et al. (e3) | 2009 | Serbia | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1:1 |

| Coleman et al. (1) | 2012 | Global | 8.4 | 2.2 | 4:1 |

MTF: male-to-female; FTM: female-to-male

Criteria for diagnosis

Transsexualism is primarily a problem of gender identity (transidentity) or gender role (transgenderism) rather than of sexuality (13). In Germany, it is diagnosed according to ICD-10 (10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems).

Criteria for diagnosis include the following:

Feeling of unease or not belonging to biological gender

Desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex

Presence of this desire for at least two years persistently

Wish for hormonal treatment and surgery

Not a symptom of another mental disorder

Not associated with intersex, genetic, or gender chromosomal abnormalities.

Psychological aspects of transsexualism

According to Senf, no disruption to an individual’s identity is comparable in scale to the development of transsexualism (14). Transsexualism is a dynamic, biopsychosocial process which those affected cannot escape. An affected individual gradually becomes aware that he or she is living in the wrong body. The feeling of belonging to the opposite sex is experienced as an unchangeable, unequivocal identity (14, 15). The individual therefore strives to change his or her inner identity. This change is associated with a change in psychosocial role, and in most cases with hormonal and/or surgical reassignment of the body to the desired gender (14). Coping with the development of transsexualism poses enormous challenges to those affected and often leads to a considerable psychological burden. In some cases this results in mental illness. Transsexualism itself need not lead to a mental disorder (14). Psychotherapeutic support is beneficial and is a major part of standard treatment and the examination of transsexual individuals in Germany (15).

Methods

Aim

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of male-to-female gender reassignment surgery on the satisfaction of transgender patients.

Data collection

Retrospective inquiry involved consecutive inclusion of 254 patients who had undergone male-to-female gender reassignment surgery involving penile inversion vaginoplasty at Essen University Hospital’s Department of Urology between 2004 and 2010. All patients received a questionnaire (eBox 2) by post, with a franked return envelope. The questions were contained within a follow-up questionnaire developed by Essen University Hospital’s Department of Urology (16). Because the process was anonymized, patients who had not sent back the questionnaire could not be contacted. The diagnosis of “transidentity” had been made previously following specialized medical examination and in accordance with ICD-10.

eBox 2. Questionnaire.

1. How satisfied are you with your outward appearance?

A) Very satisfied

B) Satisfied

C) Dissatisfied

D) Very dissatisfied

2. How satisfied were you with the gender reassignment surgery process?

A) Very satisfied

B) Satisfied

C) Mostly satisfied

D) Dissatisfied

E) Very dissatisfied

3. How satisfied are you with the aesthetic outcome of your surgery?

A) Very satisfied

B) Satisfied

C) Mostly satisfied

D) Dissatisfied

E) Very dissatisfied

4. How satisfied are you with the functional outcome of your surgery?

A) Very satisfied

B) Satisfied

C) Mostly satisfied

D) Dissatisfied

E) Very dissatisfied

5. How satisfied are you with your life now, on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied)?

6. How do you see yourself today?

A) As a woman

B) More female than male

C) More male than female

D) As a man

7. Do you feel accepted as a woman by society?

A) Yes, completely

B) Mostly

C) Rarely

D) No/Not sure

8. Has your life become easier since surgery?

A) Yes

B) Somewhat easier

C) Somewhat harder

D) No

9. Have your expectations of life as a woman been fulfilled?

A) Yes, completely

B) Mostly

C) Mostly not

D) Not at all

10. How easy is it for you to achieve orgasm?

A) Very easy

B) Usually easy

C) Rarely easy

D) Never achieve orgasm

11. If you compare your orgasm earlier as a man and now as a woman, what is your orgasm like now?

A) More intense

B) Equally/Roughly equally intense

C) Less intense

Statistics

Statistical evaluation was performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, 17.0). Correlation analyses were performed using SAS (Statistical Analysis System, 9.1 for Windows). The distribution of categorical and ordinal data was described using absolute and relative frequencies. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical and ordinal variables in independent samples. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare satisfaction scale distribution of two independent samples. This nonparametric test was used in preference to the t-test because the Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that distribution was not normal. Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed.

Results

A total of 119 completed questionnaires were returned, all of which were included in the evaluation. This represents a response rate of 46.9%. Because the questionnaires were anonymous, no data on patients’ ages could be obtained. The average age of a comparable cohort of patients at Essen University Hospital’s Department of Urology between 1995 and 2008 (17) was 36.7 years (16 to 68 years). The median time since surgery was 5.05 years (standard deviation: 1.6 years; range: 1 to 7 years). Not all patients had completed the questionnaire in full, so for some questions the total number of responses is not 119.

Following surgery, 63 of 103 patients (61.2%) were satisfied with their outward appearance as women, and a further 27 (26.2%) were very satisfied (Figure 1). 45.5% (n = 50) were very satisfied with the gender reassignment surgery process, 30% (n = 33) satisfied, 22.7% (n = 25) mostly satisfied, and 1.8% (n = 2) dissatisfied. Figure 2 shows the high rates of subjective satisfaction with the aesthetic outcome of surgery. Overall, approximately three-quarters (70 of 94 responses) reported that they were satisfied or very satisfied. A further 21 (22.3%) were mostly satisfied. Figures for satisfaction with the functional outcome of surgery were similar (Figure 3). A total of 67 of 93 respondents (72%) were satisfied or very satisfied. A further 18 patients (19.4%) were mostly satisfied. Table 2 compares the rates of subjective satisfaction with aesthetic and functional outcome with other studies.

Figure 1.

How satisfied are you with your outward appearance? (103 responses)

Figure 2.

Frequency

How satisfied are you with the aesthetic outcome of your surgery? (94 responses)

Figure 3.

How satisfied are you with the functional outcome of your surgery? (93 responses)

Table 2. Overview of subjective satisfaction (by number of study participants).

| Author | Year | No. (MTF/FTM) | Country | Satisfaction (%) | Response rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional*1 | Aesthetic*2 | Overall | |||||

| Imbimbo et al. (20) | 2009 | 139 (139/0) | Italy | 56 | 78 | 94 | – |

| Hess et al. | 2014 | 119 (119/119) | Germany | 91 | 97 | 96 | 47 |

| Perovic et al. (e4) | 2000 | 89 (89/0) | Serbia | 87 | 87 | – | – |

| Happich et al. (21) | 2006 | 56 (33/23) | Germany | – | 82 | >90 | 48 |

| Löwenberg et al. (19) | 2010 | 52 (52/0) | Germany | 84 | 94 | 69 | 49 |

| Salvador et al. (e5) | 2012 | 52 (52/0) | Brazil | 88 | – | 100 | 75 |

| Johansson et al. (e6) | 2010 | 42 (25/17) | Sweden | – | – | 95 | 70 |

| Hepp et al. (22) | 2002 | 33 (22/11) | Switzerland | 80 | 75 | – | 70 |

| de Cuypere et al. (2) | 2005 | 32 (32/0) | Belgium | 79 | 86 | – | – |

| Krege et al. (16) | 2001 | 31 (31/0) | Germany | 76 | 94 | – | 67 |

| Amend et al. (e7) | 2013 | 24 (24/0) | Germany | 100 | 100 | – | – |

| Blanchard et al. (e8) | 1987 | 22 (22/0) | Canada | 73 | 90 | – | – |

| Giraldo et al. (e9) | 2004 | 16 (16/0) | Spain | 100 | 100 | – | – |

*1Functional satisfaction includes satisfaction with depth and breadth of the neovagina and satisfaction with penetration or intercourse

*2Aesthetic satisfaction includes satisfaction with appearance of external genitalia

MTF: male-to-female; FTM: female-to-male

In order to gather information on patients’ general satisfaction with their lives, they were asked to place themselves on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“very dissatisfied”) to 10 (“very satisfied”). Of the total of 102 respondents, 7 (6.9 percent) selected scores from 1 to 3 (2 × 1, 1 × 2, 4 × 3) and 39 (38.2%) scores from 4 to 7 (4 × 4, 16 × 5, 8 × 6, 11 × 7). 56 patients (54.9%) placed themselves in the top third (32 × 8, 13 × 9, 11 × 10). 88 of 103 participants (85.4%) felt completely female following surgery, and 11 (10.7%) mostly female (Figure 4). 69 of 102 women (67.6%) saw themselves as fully accepted as women by society, 25 (24.5%) mostly, and 6 (5.9%) rarely. Two women (2.0%) were not sure of their answer to this question. Of 95 respondents, 65 (68.4%) answered with a clear “Yes” that their life had become easier since surgery. 14 (14.7%) found life somewhat easier, 9 (9.5%) somewhat harder, and 7 (7.4%) harder. Expectations of life as a woman were completely fulfilled for 51 of 102 (50.0%) women, and mostly for 41 (40.2%). The expectations of 6 (5.9%) patients were mostly not fulfilled, and those of 4 (3.9%) were not fulfilled at all.

Figure 4.

How do you see yourself today? (103 responses)

There was a correlation between self-perception as a woman (“How do you see yourself today?”) and perceived acceptance by society (r = 0.495; p<0.01). There was also a correlation between self-perception and answers to whether life had become easier since surgery (r = 0.375; p<0.01) and whether expectations of life as a woman had been fulfilled (r = 0.419; p<0.01). Patients who saw themselves completely as women reported higher scores for current satisfaction with their lives than patients who only saw themselves as more female than male (r = 0.347; p <0.01).

Patients were asked how easy they found it to achieve orgasm. A total of 91 participants answered this question: 75 (82.4%) reported that they could achieve orgasm. Of these, 19 (20.9%) still achieved orgasm very easily, 39 (42.9%) usually easily, and 17 (18.7%) rarely easily. Participants were also asked to compare their experience of orgasm before and after surgery (more intense/the same/less intense). Over half of those who answered this question (43 of 77, 55.8%) experienced more intense orgasm postoperatively, and 16 patients (20.8%) experienced the same intensity.

Discussion

According to Sohn et al. (18), subjective satisfaction rates of 80% can be expected following gender reassignment surgery. Löwenberg (19) reported 92% general satisfaction with the outcome of gender reassignment surgery. The study by Imbimbo et al. (20) found a similarly high satisfaction rate (94%); however, subjective assessment of general satisfaction and the question of whether or not patients regretted the decision to undergo gender reassignment surgery were queried in one combined question. It is likely that most patients do not actually regret their decision to undergo surgery, even though general postoperative satisfaction is limited. Löwenberg’s figures also show this (19): 69% of those asked were satisfied with their overall life situation, but 96% would opt for surgery again. In the authors’ own study population, general satisfaction with surgery was achieved in 87.4% of patients. Regardless of surgical results, over half of patients (54.9%) were in the top third (“completely satisfied”) and a further 38.2% in the middle third (“fairly satisfied”) of the general life satisfaction scale.

A retrospective survey performed by Happich (21) found more than 90% satisfaction with gender reassignment. Sexual experience following surgery is a very important factor in satisfaction with gender reassignment. It depends essentially on the functionality of the neovagina. Figures for satisfaction with functional outcome range from 56% to 84% (16, 19, 20, 22, 23). In the authors’ population, satisfaction with function was 72% (“very satisfied” and “satisfied”) or 91.4% (including also “mostly satisfied”). According to Happich (21), satisfaction with sexual experience is positively correlated with satisfaction with outcome of surgery. Other studies (16, 23– 25) have also found surgical outcome to be one of the essential factors in postoperative satisfaction. Löwenberg (19) also found a correlation between satisfaction with surgery and satisfaction with aesthetic appearance of the external genitalia. In our study, almost all patients (98.2%) were satisfied with the gender reassignment surgery process (n = 50, 45.5% “very satisfied”; n = 33, 30% “satisfied”; n = 25, 22.7% “mostly satisfied”).

The Imbimbo et al. working group (20) reported 78% satisfaction with aesthetic appearance of the neogenitalia (36% “very satisfied,” 32% “satisfied,” 10% “mostly satisfied”). Happich found 82.1% satisfaction with outcome of surgery (46 of 56 patients). Of these, 33.9% of patients reported high satisfaction and 48.2% good to medium satisfaction (21). A similar value was obtained in the survey by Hepp et al. (22). Löwenberg (19) found higher values (94%) for satisfaction with aesthetic outcome of surgery. This population included 106 male-to-female transgender individuals who underwent surgery at Essen University Hospital’s Department of Urology between 1997 and 2003. In the population described here (254 patients, 2004 to 2010) satisfaction with aesthetic outcome was still higher (96.8%).

Orgasm was possible for 82.4% of study participants. The ability to achieve orgasm was lower than in an earlier study population (16). Figures in the literature vary widely (29% to 100%) and sometimes include small case numbers (Table 3). Overall, the figures for this study match those of comparable studies of a similar size. Finally, it is not clear why more than half the participants experienced orgasm more intensely following surgery than preoperatively. One possible explanation is that postoperatively patients were able to experience orgasm in a body that matched their perception.

Table 3. Ability to achieve orgasm following male-to-female gender reassignment surgery (by number of study participants).

| Author | Year | No. of patients (n) | Able to achieve orgasm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lawrence (e10) | 2005 | 232 | 85 |

| Lawrence (e11) | 2006 | 226 | 78 |

| Hess et al. | 2014 | 119 | 82 |

| Perovic et al. (e4) | 2000 | 89 | 82 |

| Goddard et al. (30) | 2007 | 64 | 48 |

| Hage and Karim (e12) | 1996 | 59 | 80 |

| Salvador et al. (e5) | 2012 | 52 | 88 |

| Eicher et al. (e13) | 1991 | 50 | 82 |

| Bentler (e14) | 1976 | 42 | 67 |

| Jarrar et al. (e15) | 1996 | 37 | 60 |

| de Cuypere et al. (2) | 2005 | 32 | 50 |

| Krege et al. (16) | 2001 | 31 | 87 |

| Selvaggi et al. (e16) | 2007 | 30 | 85 |

| Rehman et al. (24) | 1999 | 28 | 79 |

| Amend et al. (e7) | 2013 | 24 | 96 |

| van Noort and Nicolai (e17) | 1993 | 22 | 82 |

| Blanchard et al. (e8) | 1987 | 22 | 82 |

| Eldh (e18) | 1993 | 20 | 100 |

| Schroder and Carroll (e19) | 1999 | 17 | 66 |

| Rakic et al. (e20) | 1996 | 16 | 63 |

| Ross and Need (e21) | 1989 | 14 | 85 |

| Lief and Hubschman (e22) | 1993 | 14 | 29 |

| Giraldo et al. (e9) | 2004 | 16 | 100 |

| Lindemalm et al. (e23) | 1986 | 13 | 46 |

| Rubin (e24) | 1993 | 13 | 92 |

| Stein et al. (e25) | 1990 | 10 | 80 |

| Freandt et al. (e26) | 1993 | 10 | 70 |

Limitations

The response rate of less than 50% must be mentioned as a shortcoming of this study. This may have led to a bias in the results. If all patients who did not take part in the survey were dissatisfied, up to 50.1% and 54.6% would be dissatisfied with aesthetic or functional outcome respectively. According to Eicher, the suicide rate in transgender individuals following successful surgery is no higher than in the general population (26), so suicide is a very unlikely reason for nonparticipation. Contacting transfemale patients for long-term follow-up after successful surgery is generally difficult (2, 3, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28). This may be because a patient has moved since successful surgery, for example, (21). Postoperative contact is particularly difficult in countries such as Germany which have no central registers. Response rates to surveys in retrospective research are between 19% (28) and 79% (29). Goddard et al. obtained a response rate of 30% in a retrospective survey following gender reassignment surgery (30). A follow-up survey performed by Löwenberg et al. had a similar response rate, 49% (19). It is also possible that the positive results of our survey represent patients’ wish for social desirability rather than the real situation. However, this cannot be verified retrospectively.

Conclusion

Taking into account the limitations mentioned above, the high rates of subjective satisfaction with outward female appearance and with aesthetic and functional outcome of surgery indicate that the study participants benefited from gender reassignment surgery.

Key Messages.

At the core of the transsexual experience lies the awareness that one is a member of a realistically perceived anatomical sex (matching of genotype and phenotype), but a subjective feeling of belonging to the other gender.

Change to the gender inwardly identified with is associated with a change in psychosocial role and in most cases with hormonal and surgical reassignment of the body to the desired gender.

Although transsexualism itself is not a mental disorder, it can favor the development of mental problems.

Transsexualism is a dynamic, biopsychosocial process which affected individuals cannot escape.

The high rates of subjective satisfaction with outward female appearance and with aesthetic and functional outcome of surgery indicate that study participants benefited from gender reassignment surgery.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Hess has received reimbursement of conference fees and travel expenses from AMS American Medical Systems.

The other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13 [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Cuypere G, T’Sjoen G, Beerten R, et al. Sexual and physical health after sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34:679–690. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-7926-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhejne C, Lichtenstein P, Boman M, Johansson ALV, Långström N, Landén M. Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: Cohort Study in Sweden. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hepp U, Kraemer B, Schnyder U, Miller N, Delsignore A. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender identity disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:259–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hage JJ, Karim RB. Ought GIDNOS get nought? Treatment options for nontranssexual gender dysphoria. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1222–1227. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200003000-00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein C, Gorzalka BB. Sexual functioning in transsexuals following hormone therapy and genital surgery: a review. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2922–2939. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gijs L, Brewaeys A. Surgical treatment of gender dysphoria in adults and adolescents: Recent developments, effectiveness, and challenges. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2007;181 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitze C, Osburg S. Transsexualism in Germany: empirical data on epidemiology and application of the German Transsexuals’ Act during its first ten years. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25:409–425. doi: 10.1007/BF02437583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Cuypere G, van Hemelrijck M, Michel A, et al. Prevalence and demography of transsexualism in Belgium. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biosnich JR, Brown GR, Shipherd JC, Kauth M, Piegari RI, Bossart RM. Prevalence of gender identity disorder and suicide risk among transgender veterans utilizing veterans health administration care. Am J Public Health. 2013;103 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Kesteren PJ, Gooren LJ, Megens JA. An epidemiological and demographic study of transsexuals in the Netherlands. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25:589–600. doi: 10.1007/BF02437841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrels L, Kockott G, Michael N, et al. Sex ratio of transsexuals in Germany: The development over three decades. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:445–448. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102006445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichlo HG. Leistungsrechtliche und sozialmedizinische Kriterien für somatische Behandlungsmaßnahmen bei Transsexualismus: Neue MDK-Begutachtungsanleitung. Blickpunkt der Mann. 2010;8 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senf W. Transsexualität. Psychotherapeut. 2008;53 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker S, Bosinski HAG, Clement U, et al. Behandlung und Begutachtung von Transsexuellen Standards der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Sexualforschung, der Akademie für Sexualmedizin und der Gesellschaft für Sexualwissenschaft. Psychotherapeut. 1997;42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krege S, Bex A, Lummen G, Rubben H. Male-to-female transsexualism: a technique, results and long-term follow-up in 66 patients. BJU Int. 2001;88:396–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi Neto R, Hintz F, Krege S, Rübben H, vom Dorp F. Gender reassignment surgery—a 13 year review of surgical outcomes. Int Braz J Urol. 2012;38 doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382012000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sohn MH, Hatzinger M, Wirsam K. Operative Genitalangleichung bei Mann-zu-Frau-Transsexualität: Gibt es Leitlinien oder Standards? [Genital reassignment surgery in male-to-female transsexuals: do we have guidelines or standards?]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2013;45:207–210. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Löwenberg H, Lax H, Neto RR, Krege S. Complications, subjective satisfaction and sexual experience by gender reassignment surgery in male-to-female transsexual. Z Sexualforsch. 2010;23:328–347. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imbimbo C, Verze P, Palmieri A, et al. A report from a single institute’s 14-year experience in treatment of male-to-female transsexuals. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2736–2745. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Happich FJ. Postoperative Ergebnisse bei Transsexualität unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Zufriedenheit - eine Nachuntersuchung. Dissertation Universität Essen-Duisburg. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hepp U, Klaghofer R, Burkhard-Kubler R, Buddeberg C. Behandlungsverläufe transsexueller Patienten: Eine katamnestische Untersuchung [Treatment follow-up of transsexual patients. A catamnestic study] Nervenarzt. 2002;73:283–288. doi: 10.1007/s00115-001-1225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eldh J, Berg A, Gustafsson M. Long-term follow up after sex reassignment surgery. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg Suppl. 1997;31:39–45. doi: 10.3109/02844319709010503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehman J, Lazer S, Benet AE, Schaefer LC, Melman A. The reported sex and surgery satisfactions of 28 postoperative male-to-female transsexual patients. Arch Sex Behav. 1999;28:71–89. doi: 10.1023/a:1018745706354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence AA. Factors associated with satisfaction or regret following male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:299–315. doi: 10.1023/a:1024086814364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eicher W. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1992. Transsexualismus: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Geschlechtsumwandlung. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobato MI, Koff WJ, Manenti C, et al. Follow-up of sex reassignment surgery in transsexuals: a Brazilian cohort. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:711–715. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9074-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rauchfleisch U, Barth D, Battegay R. Resultate einer Langzeitkatamnese von Transsexuellen Results of long-term follow-up of transsexual patients] [Nervenarzt. 1998;69:799–805. doi: 10.1007/s001150050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen T. A follow-up study of operated transsexual males. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63:486–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1981.tb00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goddard JC, Vickery RM, Qureshi A, Summerton DJ, Khoosal D, Terry TR. Feminizing genitoplasty in adult transsexuals: early and long-term surgical results. BJU Int. 2007;100:607–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pauly IB. The current status of the change of sex operation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1968;147:460–471. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walinder J. Transsexualism: definition, prevalence and sex distribution. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1968;203:255–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1968.tb02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoenig J, Kenna JC. The prevalence of transsexualism in England and Wales. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;124:181–190. doi: 10.1192/bjp.124.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross MW, Walinder J, Lundstrom B, Thuwe I. Cross-cultural approaches to transsexualism. A comparison between Sweden and Australia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63:75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1981.tb00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Gorman EC. A retrospective study of epidemiological and clinical aspects of 28 transsexual patients. Arch Sex Behav. 1982;11:231–236. doi: 10.1007/BF01544991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsoi WF. The prevalence of transsexualism in Singapore. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78:501–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb06373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eklund PL, Gooren LJ, Bezemer PD. Prevalence of transsexualism in The Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:638–640. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.5.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landén M, Walinder J, Lundstrom B. Prevalence, incidence and sex ratio of transsexualism. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:221–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson P, Sharp C, Carr S. The prevalence of gender dysphoria in Scotland: a primary care study. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:991–992. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haraldsen IR, Dahl AA. Symptom profiles of gender dysphoric patients of transsexual type compared to patients with personality disorders and healthy adults. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:276–281. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Olsson SE, Moller AR. On the incidence and sex ratio of transsexualism in Sweden, 1972-2002. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:381–386. doi: 10.1023/a:1024051201160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Gomez-Gil E, Trilla Garcia A, Godas Sieso T, et al. [Estimation of prevalence, incidence and sex ratio of transsexualism in Catalonia according to health care demand] Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2006;34:295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Vujovic S, Popovic S, Sbutega-Milosevic G, Djordjevic M, Gooren L. Transsexualism in Serbia: a twenty-year follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1018–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Perovic SV, Stanojevic DS, Djordjevic ML. Vaginoplasty in male transsexuals using penile skin and a urethral flap. BJU Int. 2000;86:843–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Salvador J, Massuda R, Andreazza T, et al. Minimum 2-year follow up of sex reassignment surgery in Brazilian male-to-female transsexuals. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Johansson A, Sundbom E, Hojerback T, Bodlund O. A five-year follow-up study of Swedish adults with gender identity disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:1429–1437. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Amend B, Seibold J, Toomey P, Stenzl A, Sievert KD. Surgical reconstruction for male-to-female sex reassignment. Eur Urol. 2013;64:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Blanchard R, Legault S, Lindsay WR. Vaginoplasty outcome in male-to-female transsexuals. J Sex Marital Ther. 1987;13:265–275. doi: 10.1080/00926238708403899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Giraldo F, Esteva I, Bergero T, et al. Corona glans clitoroplasty and urethropreputial vestibuloplasty in male-to-female transsexuals: the vulval aesthetic refinement by the Andalusia Gender Team. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1543–1550. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000138240.85825.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Lawrence AA. Sexuality before and after male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34 doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-1793-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Lawrence AA. Patient-reported complications and functional outcomes of male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:717–727. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Hage JJ, Karim RB. Sensate pedicled neoclitoroplasty for male transsexuals: Amsterdam experience in the first 60 patients. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;36:621–624. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Eicher W, Schmitt B, Bergner CM. Darstellung der Methode und Nachuntersuchung von 50 Operierten. Z Sexualforsch. 1991;4 [Google Scholar]

- e14.Bentler PM. A typology of transsexualism: gender identity theory and data. Arch Sex Behav. 1976;5:567–584. doi: 10.1007/BF01541220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Jarrar K, Wolff E, Weidner W. Langzeitergebnisse nach Geschlechtsangleichung bei männlichen Transsexuellen. Urologe A. 1996;35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Selvaggi G, Monstrey S, Ceulemans P, T’Sjoen G, De Cuypere G, Hoebeke P. Genital sensitivity after sex reassignment surgery in transsexual patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:427–433. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000238428.91834.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.van Noort DE, Nicolai JP. Comparison of two methods of vagina construction in transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:1308–1315. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199306000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Eldh J. Construction of a neovagina with preservation of the glans penis as a clitoris in male transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:895–900. discussion 901-893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Schroder M, Carroll RA. New women: Sexological outcomes of male-to-female gender reassignment surgery. J Sex Educ Ther. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- e20.Rakic Z, Starcevic V, Maric J, Kelin K. The outcome of sex reassignment surgery in Belgrade: 32 patients of both sexes. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25:515–525. doi: 10.1007/BF02437545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Ross M, Need J. Effects of adequacy of gender reassignment surgery on psychological adjustment: A follow-up of fourteen male-to-female patients. Arch Sex Behav. 1989;18 doi: 10.1007/BF01543120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Lief HI, Hubschman L. Orgasm in the postoperative transsexual. Arch Sex Behav. 1993;22:145–155. doi: 10.1007/BF01542363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Lindemalm G, Korlin D, Uddenberg N. Long-term follow-up of “sex change“ in 13 male-to-female transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav. 1986;15:187–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01542412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Rubin SO. Sex-reassignment surgery male-to-female. Review, own results and report of a new technique using the glans penis as a pseudoclitoris. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1993;154:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Stein M, Tiefer L, Melman A. Followup observations of operated male-to-female transsexuals. J Urol. 1990;143:1188–1192. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Freundt I, Toolenaar TA, Huikeshoven FJ, Jeekel H, Drogendijk AC. Long-term psychosexual and psychosocial performance of patients with a sigmoid neovagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1210–1214. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90283-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Baranyi A, Piber D, Rothenhausler HB. Mann-zu-Frau-Transsexualismus. Ergebnisse geschlechtsangleichender Operationen in einer biopsychosozialen Perspektive. [Male-to-female transsexualism. Sex reassignment surgery from a biopsychosocial perspective] Wien Med Wochenschr. 2009;159:548–557. doi: 10.1007/s10354-009-0693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]