Examination of the relations between brain electrical activity and emotion can be greatly informed by also considering cognition. Psychologists have long struggled with creating a framework for conceptualizing relations between affect and reason (Izard, 1993; Lazrus, 1982; Zajonc, 1980), and more recently have focused on examining interactions between cognition and emotion from both behavioral and brain-based approaches (Sherer, 2003). Although, the field of developmental psychology has traditionally compartmentalized emotion development and cognitive development, there have been recent attempts to integrate these processes conceptually using a neuroscience perspective (e.g., Bell & Deater-Deckard, 2007; Dennis, 2010; Lewis & Todd, 2007; Posner & Rothbart, 2000; Thompson, Lewis, & Calkins, 2008; Zelazo & Cunningham, 2007). Empirical studies with EEG and ERP measures can be used to support these conceptual models (see Fox, Kirwan, & Reeb-Sutherland, this volume, for specifics on measuring EEG/ERP associated with emotion).

In this chapter we propose that the incorporation of cognitive processes in the study of EEG/ERP and emotion relations is state of the science with respect to the examination of individual differences in development (Calkins & Bell, 2010). We begin by examining different models of interrelations between emotion and cognition and selectively review developmental EEG/ERP studies that illustrate each model, including some of our own work. Then we summarize our current conceptualization of emotion-cognition integration in early development (Bell & Deater-Deckard, 2007; Bell & Wolfe, 2004).

Associations between Emotion and Cognition

Much like Carlson and Wang (2007), we focus on three basic models for examining the interaction between emotion and cognition. The first two models are unidirectional so as to simplify the study of emotion-cognition relations. It is more likely, however, that emotion and cognition processes continuously influence each other in a dynamic manner (Lewis, 2005), much like the third model.

Emotion influences cognitive outcomes

In the first model, regulation of emotion may have an impact on cognitive outcomes; hence, emotions act to organize thinking, learning, and action (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004). Using this model, researchers may manipulate emotion in the experimental situation and inspect the effect on cognitive performance (Gray, 2001; Richards & Gross, 2000). Similarly, researchers may examine normal variations in emotion reactivity and emotion regulation (i.e., temperament) to study impact of emotion on cognitive outcomes.

This model has guided several studies in our program of research, including those in which regulatory aspects of temperament were used as a proxy for emotion. With a sample of 8-month-olds, we sought to predict performance level on an infant executive function task (looking A-not-B, requiring working memory and inhibitory control skills). The percentage of correct classification into high and low cognitive performance groups using measures of task-related frontal/parietal EEG coherence and heart period, as well as maternal-rated infant distress to limitations, was 93% (Bell, 2009). We had, however, predicted that other temperament traits (i.e., duration of orienting, soothability) would be associated with cognitive outcomes because of their links to more regulatory aspects of temperament. This surprising temperament finding led us to examine other aspects of reactivity in relation to cognitive performance.

In a recent study from our lab, we examined fear reactivity in relation to cognitive measures of novelty preference during infancy. In addition to examining mother-rated infant temperament as in our previous infant work, we made behavioral observations of fear reactivity and we recorded frontal EEG asymmetries in a group of 10-month-old infants. EEG was recorded at baseline and during fear tasks and our cognitive outcome task, which was novelty preference measured via the visual recognition memory paradigm. Previous research has shown that fear reactivity is associated with right frontal EEG asymmetry in infants (Buss, Schumacher, Dolski, Goldsmith, Davidson, & Kalin, 2003; see Miskovic & Schmidt, this volume, for a brain-body lateralization model of temperamental fear) and infants who present with high fear reactivity also typically exhibit heightened levels of attention to their environments (Calkins, Fox, & Marshall, 1996). Thus, we hypothesized that underlying patterns of general fearfulness may enhance the information processing that is required for the encoding and retrieval associated with recognition memory. Fear reactivity therefore should be associated with novelty preference during recognition memory tasks. We also expected that infants who exhibited higher levels of fear reactivity would have relative right frontal EEG asymmetry during baseline recordings and during the cognitive processing associated with recognition memory.

We found that as a group the infants exhibited left frontal EEG asymmetry at baseline. However, for some of those infants the left frontal baseline EEG asymmetry changed to right frontal EEG asymmetry in the context of specific fear tasks that were either social (stranger approach) or non-social (scary masks, jumping toy spider) in nature. We were able to predict the level of fear behaviors in each context from the magnitude of change from baseline frontal EEG asymmetry to task-related frontal EEG asymmetry (Diaz & Bell, 2010b). What was most salient about our ability to predict the level of fear using frontal EEG asymmetry is that we did not recruit infants based on their temperamental fear reactivity. Furthermore, when we divided the infants into higher and lower fear reactivity groups based on behavioral responses in the three contexts, the more fearful infants also exhibited novelty preference in the recognition memory paradigm. In contrast to our hypothesis, fearful infants demonstrated left frontal EEG asymmetry during the familiarization and paired comparison portions of the recognition memory task. The left frontal areas typically are associated with better feature discrimination during attentional processing (Diaz & Bell, 2009a).

We have also examined the impact of temperament-based emotion on cognitive outcomes during early childhood. With a group of children who were 4½ years of age, we were able to correctly classify 90 percent of the children into high and low cognitive performance groups using task-related frontal EEG power values, maternal-rated child temperament (i.e., approach), and receptive language (Wolfe & Bell, 2004). The cognitive outcomes were measures of early childhood executive function (Day/Night and yes/no). With a separate group of preschool children between 3 ½ and 4 ½ years of age, we showed that frontal and temporal EEG, as well as maternal rated temperament (i.e., effortful control), were associated with executive function performance (Wolfe & Bell, 2007). Thus, with infant as well as early childhood samples, we have demonstrated that EEG measures, as well as regulatory and sometimes reactive aspects of temperament (as a proxy for emotion), were predictors of cognitive task performance.

Cognition influences emotion-related outcomes

In the second model, thinking, learning, and action serve to regulate emotions (Cole et al., 2004). Researchers using this model may examine the effect of cognitive inhibitory responses or other cognitive strategies on emotion regulation (Ochsner & Gross, 2005, 2008). They may also examine how temperament-related influences on cognition may affect the regulation of emotion. Examples of findings from three research teams are highlighted. These teams focus on ERP markers of attentional processing associated with emotion regulation (Dennis, 2010).

Lewis and colleagues have focused on ERP indices of emotion regulation, with particular emphasis on individual differences in attention-related cognitive processes that are recruited for regulating negative emotion (Lamm & Lewis, 2010; Lewis & Stieben, 2004; Woltering & Lewis, 2009). The ERP waveform of interest was the N2, which is associated with effortful attention and response inhibition. One of the anatomical correlates of the N2 is the anterior cingulate cortex, a prominent structure associated with the Executive Attention System. During a go/no-go task using photos of happy, angry, or neutral facial expressions, preschool children showed greatest frontal N2 amplitudes and fastest N2 latencies to angry faces and smallest amplitudes and longest latencies to happy faces (Lewis, Todd, & Honsberger, 2007). Furthermore, there was a negative correlation between parent-reported fearfulness (measured via temperament questionnaire) and latency of the N2 to angry faces when they appeared in the go condition. Because the N2 effects varied with facial expressions of emotion, Lewis and colleagues interpreted the N2 as an index of emotion regulation.

Dennis and colleagues (Dennis, Malone, & Chen, 2009) also utilized happy, fearful, and sad faces with children as they performed an attentional task. Differing from the procedures used by Lewis and colleagues, the emotion stimuli used by Dennis were distracters embedded in the attentional task and not the actual stimuli to which the participants were instructed to respond. Larger P1 and frontal Nc amplitudes, associated with early attention processing, to distracting fearful and sad faces were correlated with more effective emotion regulation in 5- to 9-year-old children, with emotion regulation measured as performance on the attention task and as maternal report.

Perez-Edgar and Fox (2007) examined temperament-related attentional differences associated with emotion regulation in 7-year-old children. When the stimuli were affective words, children with higher maternal ratings in attentional control exhibited greater right frontal N2 and lower amplitude P3 to all words regardless of valence. Thus, individual differences in temperament-based attentional control were associated with behavioral and brain-related indices of emotion.

Emotion and cognition as outcomes

The third model assigns both cognition and emotion as outcomes. Zelazo presents an intriguing hypothesis about emotion-cognition associations in his work on “hot” and “cool” executive functions (e.g., Kerr & Zelazo, 2004). Cool executive functions are those traditionally considered to be focused on cognitive, goal-directed problem solving and they are associated with the functioning of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Hot executive functions are associated with problem solving or with decision making that has significant emotional consequences. Hot functions are associated with functioning of the orbitofrontal cortex. When the problem solving is focused on the regulation of emotion, Zelazo considers executive function to be the same as emotion regulation (Zelazo & Cunningham, 2007).

Zelazo and colleagues use the Children's Gambling Task to study hot executive function. In this task, children play the game in order to receive candies as a reward. They must choose cards from one of two decks in order to receive the candy, with each deck designed to link amount of reward with amount of potential loss. Thus, the children's cognitive decisions are affectively motivated (Kerr & Zelazo, 2004).

Affective responding is also evident in a study by Perez-Edgar and Fox (2005). Seven-year-old children performed an attentional cuing task under neutral conditions and then performed that same task when told that performance would determine whether or not they would have to give a speech. The task requires orienting to sensory stimuli (bottom-up processing) and the speech condition layers on contextual and individual characteristics (top-down mechanisms). Under the potential speech condition, reaction times were faster and there were more errors. Children with higher levels of maternal-rated shyness had faster reaction times to negative (lose points) versus positive (gain points) attentional cues and also had greater N1 and N2 amplitudes relative to the low shy children (Perez-Edgar & Fox, 2005). These temperament group differences were not evident during the neutral task condition, indicating that the interactions between emotion and cognition only occurred during the motivationally significant potential speech condition. This finding highlights the value of assessing EEG/ERP components of emotion regulation during emotionally salient task conditions.

Dennis and Chen (2007) report a similar finding with adults. As previously noted, this research team has developed a protocol where happy, fearful, and sad faces are used as distracters embedded in an attentional task. When instructed to respond to non-emotion stimuli during the task, adults who self-rated as high in threat sensitivity exhibited enhanced N2 to fearful faces and this was linked to sustained executive attention performance. For adults who self-rated as low in threat sensitivity, greater N2 was associated with decrements in executive attention. In this study, the fearful faces provided the context for the coupling of emotion and cognition.

Brain electrophysiology measures have proven important for the examination of emotion-cognitive associations. Thus far we have described various EEG and ERP correlates of emotion, with an emphasis on related cognitive processes. Next we turn to a brief discussion of the use of electrophysiology in studying the integration of emotion and cognition during development. We begin with a definition of integration and then highlight the brain systems that we (Bell & Deater-Deckard, 2007; Bell & Wolfe, 2004) and others (e.g., Dennis, 2010; Lewis, 2005; Rothbart, Sheese, & Posner, 2007) propose are the foundations for emotion-cognition integration.

Conceptual Framework for Emotion-cognition Integration

Gray (2004) defines integration with respect to emotion and cognition. When conceptually linked, cognitive and emotion processes are not completely separable and their subprocesses influence each other selectively. Specific emotional states can differentially influence information processing, and cognitive control can modulate various emotion experiences (Gray, 2001). This is illustrated by the Perez-Edgar and Fox (2005) and Dennis and Chen (2007) studies discussed above. In each study, individual differences in emotion regulation and performance on attentional tasks were associated with context-related patterns of brain electrical activity.

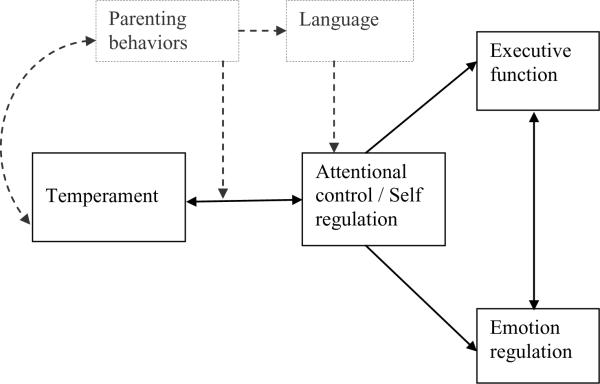

Our conceptualization of emotion-cognition integration incorporates the bi-directional influences between emotion and cognition that are the focus of the third model we described above (see Figure 1). Our model is focused on the brain mechanisms of the Executive Attention System, encompassing the anterior cingulate cortex and other areas of the prefrontal cortex (see Bell & Deater-Deckard, 2007, for details of this model). The anterior cingulate has sections that process cognitive and emotional information separately. The cognitive section is connected with the prefrontal cortex, parietal cortex, and premotor and supplementary motor areas and is activated by tasks that involve choice selection from conflicting information (Engle, 2002). The emotion section is connected with the orbitofrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus, among other brain areas, and is activated by tasks with emotion content (Fichtenholtz, Dean, Dillon, Yamanski, McCarthy, & LaBar, 2004). It was previously thought that there was always activation of the cognitive section and suppression of the affective section during cognitive processing and activation of the affective section along with suppression of the cognitive subdivision during emotion processing, thus rendering emotion and cognition as separate processes neurologically (Bush, Luu, & Posner, 2000). Recent brain imaging studies with adults, however, show that the activation-suppression relations between cognitive and affective sections of the anterior cingulate cortex can be complex. For example, emotionally-incongruent trails on the word-face Stroop (e.g., a positive word overlaid upon a face with a negative valence) is associated with increased activation of the cognitive subdivision of the anterior cingulate cortex (Haas, Omura, Constable, & Canli, 2006). Similarly, during the emotional counting Stroop there is decreased activity in the affective subdivision of the anterior cingulate, but increased activity in that same subdivision during the display of emotionally valenced words (Bush et al, 2000). This research finding, along with Posner and Rothbart's strong developmental framework of the attentional control associated with certain self-regulatory aspects of temperament, is one of the reasons for the current focus on the anterior cingulate cortex and the Executive Attention System in the study of the development of emotion-cognition integration (Rothbart, 2004; Rothbart et al., 2007). Nondevelopmental conceptualizations of emotion-cognition integration/interactions have focused on other brain structures, such as the amygdala (Phelps, 2006).

Figure 1.

Model of hypothesized emotion-cognition relations. Attentional control directly influences both emotion and cognition. We hypothesize that with development, emotion and cognition become increasingly correlated, with constitutional differences in child temperament contributing to the developmental outcomes of attentional control, executive function, and emotion regulation (adapted from Bell & Wolfe, 2007).

We consider temperament-based attentional control as critical for the self-regulation associated with emotion-cognition integration, as do other developmental scientists (Henderson & Wachs, 2007; Rothbart et al., 2007). Early regulation of temperament-based emotional distress is enhanced by the development of attentional control associated with the Executive Attention System (Ruff & Rothbart, 1996). Attentional control is required for resolving conflict among thoughts, feelings, and responses (Rueda, Posner, & Rothbart, 2005) and, thus, important for the developing self-regulation of both emotion and cognitive processes (Kopp, 2002).

We hypothesize that attentional control processes exert influence on both cognition and emotion so that they may become increasingly correlated over time, with interlocking developmental trajectories demonstrating the significance of both cognition and emotion as outcome measures. Currently, we are examining the development of attentional control, cognition (i.e., executive functions), and emotion regulation across infancy and early childhood using both behavioral and EEG measures. In this longitudinal study we are using separate measures of cognition and emotion so that we can track the developing trajectories for each. We are also collecting measures of temperament and language, given the influence of each on cognitive and emotion development (Henderson & Wachs, 2007; Wolfe & Bell, 2004, 2007).

Some of our initial findings show associations between attentional processing measures of looking time, emotion regulation skills during distress, and frontal EEG activity (Diaz & Bell, 2009). Specifically, 5-month-old infants who process information quickly (i.e., are short lookers during familiarization of a stimulus, as opposed to long lookers; Colombo, Mitchell, Coldren, & Freeseman, 1991), appear less distressed during the arm restraint task, as indicated by behaviors and frontal EEG activity during the task. Specifically, the short lookers are more likely than the long lookers to employ a regulatory strategy where they focus on something other than the source of their distress (i.e., mother) during the arm restraint task. Furthermore, the short lookers exhibit greater task-related increases in frontal EEG power during arm restraint than the long lookers. We and others have interpreted these increases in frontal EEG power as the electrophysiology associated with effortful cognitive processing (Bell, 2001, 2002: Morasch, & Bell, 2009; Orekhova, Stroganova, & Posikera, 2001). We use the same interpretation during the arm restraint task. When the short looking infants were faced with duress, they used their efficient information processing skills and their effortful control of attention to regulate.

When these same children are 24 months of age, performance on cognition and emotion tasks, as well as task-related changes in frontal EEG, are related to measures of inhibitory control (Morash & Bell, in press). Specifically, we were able to predict 29% of the variance on a maternal-report measure of temperament-related inhibitory control using performance on a cognitive conflict task (A-not-B with invisible displacement), a delay task (crayon delay), a compliance task (acceptance of EEG electrodes), and verbal ability, although performance on the delay task did not contribute unique variance to the model. In addition, we could also predict 29% of the variance on the maternal-report of temperament-related inhibitory control using conflict task EEG, after controlling for performance on the conflict task. Specifically, lateral frontal power values in each hemisphere, as well as task performance, provided unique variance to the model. As we continue to see these children throughout early childhood, we will gather the data to be able to test our hypothesis that our cognitive and emotion-related measures will become more correlated over time.

We include language and parenting behaviors in our model as well (Bell & Wolfe, 2007). The development of language, in conjunction with continuing development of the frontal cortex, may encourage early advances in the voluntary control of emotion and cognition (Ruff & Rothbart, 1996). Maternal interactive style is related to emotion regulation behaviors in infants and young children (e.g., Calkins & Bell, 2010); however, not much attention has been given to the role of parenting to the development of executive functions. It is likely that infant cognitive status (i.e., length of attention, memory) interacts with some aspects of caregiving to influence cognitive development (Colombo, & Saxon, 2002). In our model, parenting behaviors are moderators of the associations between temperament and attentional control. For example, caregivers may support infants' attentional development in efforts to relieve early infant distress (Ruff & Rothbart, 1996). We are examining if there are specific parental behaviors that are associated either concurrently or longitudinally with the development of attentional control and, thus, with associations between executive functions and emotion regulation.

Concluding Remarks

There are different ways of conceptualizing emotion-cognition integration (Calkins & Bell, 2010) and we have emphasized the regulatory aspects of emotion and cognition associated with attentional control in this brief chapter. This particular framework allows for the identification of common psychobiological processes and we have presented three basic models for examining these relations using EEG/ERP measures. We have shown that there are complex processes by which emotions relate to cognition and ultimately to developmental outcome. Thus, we propose that the examination of emotion must include concurrent examination of cognitive processes in order to understand these dynamic and neurologically related processes.

Acknowledgments

Some of the research reported in this chapter was supported by grants HD049878 and HD043057 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

References

- Bell MA. Brain electrical activity associated with cognitive processing during a looking version of the A-not-B object permanence task. Infancy. 2001;2:311–330. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0203_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA. Infant 6–9 Hz synchronization during a working memory task. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:450–458. doi: 10.1017.S0048577201393174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA. A psychobiological perspective on working memory performance at 8 months of age. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01684.x. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, Deater-Deckard K. Biological systems and the development of self-regulation: Integrating behavior, genetics, and psychophysiology. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:409–420. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181131fc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, Wolfe CD. Emotion and cognition: An intricately bound developmental process. Child Development. 2004;75:366–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, Wolfe CD. The cognitive neuroscience of early socioemotional development. In: Brownell CA, Kopp CB, editors. Socioemotional development in the toddler years. Guilford; New York: 2007. pp. 345–369. [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss K, Schumacher J, Dolski I, Goldsmith H, Davidson R, Kalin N. Right frontal brain activity, cortisol, and withdrawal behavior in 6-month-old infants. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117:11–20. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.117.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Bell MA. Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition. American Psychology Association Press; Washington, D.C.: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA, Marshall TR. Behavioral and physiological antecedents of inhibition in infancy. Child Development. 1996;67:523–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Wang TS. Inhibitory control and emotion regulation in preschool children. Cognitive Development. 2007;22:489–510. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo J, Mitchell D, Coldren J, Freeseman L. Individual differences in infant visual attention: Are short lookers faster processors or feature processors? Child Development. 1991;62:1247–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis TA. Neurophysiological markers for child emotion regulation from the perspective of emotion-cognition integration: Current directions and future challenges. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35:212–230. doi: 10.1080/87565640903526579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis TA, Chen C-C. Neurophysiological mechanisms in the emotional modulation of attention: The interplay between threat sensitivity and attentional control. Biological Psychology. 2007;76:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis TA, Malone MM, Chen C-C. Emotional face processing and emotion regulation in children: An ERP study. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2009;34:85–102. doi: 10.1080/87565640802564887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Bell MA. Information processing efficiency and emotion regulation at 5 months. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.12.011. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Bell MA. Individual differences in fear reactivity in infancy: Frontal EEG asymmetry and novelty preference. 2010a Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Bell MA. Frontal EEG asymmetry and fear reactivity in social and non-social contexts at 10 months of age. 2010b doi: 10.1002/dev.20612. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW. Working memory capacity as executive attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fichtenholtz HM, Dean HL, Dillon DG, Yamasaki H, McCarthy G, LaBar KS. Emotion-attention network interactions during visual-oddball task. Cognitive Brain Research. 2004;20:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JR. Emotion modulation of cognitive control: Approach-withdrawal states double-dissociate spatial from verbal two-back task performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130:436–452. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JR. Integration of emotion and cognitive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Haas BW, Omura K, Constable RT, Canli T. Interference produced by emotional conflict associated with anterior cingulate activation. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;6:152–156. doi: 10.3758/cabn.6.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson HA, Wachs TD. Temperament theory and the study of cognition-emotion interactions across development. Developmental Review. 2007;27:396–427. [Google Scholar]

- Izard C. Four systems for emotion activation: Cognitive and noncognitive processes. Psychological Review. 1993;100:68–90. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr A, Zelazo PD. Development of “hot“ executive function: The children's gambling task. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55:148–157. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. The co-development of attention and emotion regulation. Infancy. 2002;3:199–208. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Lewis MD. Developmental change in the neurophysiological correlates of self-regulation in high- and low-emotion conditions. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35:156–176. doi: 10.1080/87565640903526512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition. American Psychologist. 1982;37:1019–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD. Bridging emotion theory and neurobiology through dynamic systems modeling. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28:169–245. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x0500004x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Stieben J. Emotion regulation in the brain: Conceptual issues and directions for developmental research. Child Development. 2004;75:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Todd RM. The self-regulating brain: Cortical-subcortical feedback and the development of intelligent action. Cognitive Development. 2007;22:406–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Todd RM, Honsberger MJM. Event-related potential measures of emotion regulation in early childhood. NeuroReport. 2007;18:61–65. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328010a216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasch KC, Bell MA. Patterns of frontal and temporal brain electrical activity during declarative memory performance in 10-month-old infants. Brain and Cognition. 2009;71:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasch KC, Bell MA. The role of inhibitory control in behavioral and physiological expressions of toddler executive function. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.07.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. Cognitive emotion regulation: Insights from social cognitive and affective neuroscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orekhova EV, Stroganova TA, Posikera IN. Alpha activity as an index of cortical inhibition during sustained internally controlled attention in infants. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2001;112:740–749. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Edgar K, Fox NA. A behavioral and electrophysiological study of children's selective attention under neutral and affective conditions. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2005;6:89–118. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Edgar K, Fox NA. Temperamental contributions to children's performance in an emotion-word processing task: A behavioral and electrophysiological study. Brain and Cognition. 2007;65:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA. Emotion and cognition: Insights from studies of the human amygdala. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:27–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:427–441. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and memory: The cognitive costs of keeping one's cool. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:410–424. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Temperament and the pursuit of an integrated developmental \ psychology. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Sheese BE, Posner MI. Executive attention and effortful control: Linking temperament, brain networks, and genes. Child Development Perspectives. 2007;1:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda MR, Posner MI, Rothbart MK. The development of executive attention: Contributions to the emergence of self-regulation. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:573–594. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff HA, Rothbart MK. Attention in early development: Themes and variations. Oxford; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer KR. Introduction: Cognitive components of emotion. In: Davidson RJ, Scherer KR, Goldsmith HH, editors. Handbook of affective sciences. Oxford; New York: 2003. pp. 563–571. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Lewis MD, Calkins SD. Reassessing emotion regulation. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2:124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe CD, Bell MA. Working memory and inhibitory control in early childhood: Contributions from electrophysiology, temperament, and language. Developmental Psychobiology. 2004;44:68–83. doi: 10.1002/dev.10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe CD, Bell MA. Sources of variability in working memory in early childhood: A consideration of age, temperament, language, and brain electrical activity. Cognitive Development. 2007;22:431–455. [Google Scholar]

- Woltering S, Lewis MD. Developmental pathways of emotion regulation in childhood: A neuropsychological perspective. Mind, Brain, and Education. 2009;3:160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc RB. Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist. 1980;35:151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Cunningham WA. Executive function: Mechanisms underlying emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. Guilford; New York: 2007. pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]