Abstract

Tissue maintenance and homeostasis can be achieved through replacement of dying cells by differentiating precursors, self-renewal of terminally differentiated cells or relies heavily on cellular longevity in poorly regenerating tissues. Regulatory T (Treg) cells represent an actively dividing cell population with critical function in suppression of lethal immune-mediated inflammation. The plasticity of Treg cells has been actively debated as it could factor importantly in protective immunity or autoimmunity. Here, by using inducible labeling and tracking of Treg cell fate in vivo, or transfers of highly purified Treg cells, we demonstrate remarkable stability of this cell population under physiologic and inflammatory conditions. Our results suggest that self-renewal of mature Treg cells serves as a major mechanism of maintenance of the Treg cell lineage in adult mice.

Continuous replacement of differentiated cells within some tissues, such as the gut epithelium, is achieved by their de novo generation from a pool of precursor cells (1), whereas other tissues with reduced regenerative and proliferative capacity such as the central nervous system rely largely on cellular longevity for maintenance. Replication and self-renewal of differentiated cells, as shown for pancreatic β-cells, represents another potential mechanism underlying tissue maintenance (2). The latter strategy raises the issue of stability vs. plasticity of a differentiated state, which is of particular import for proliferating cell populations of the immune system. Regulatory T (Treg) cells, defined by expression of the transcription factor Foxp3, represent a dedicated suppressor cell type whose maintenance is required throughout life to restrain fatal autoimmunity (3–7). The instability of the Treg cell fate, i.e. their ability to further differentiate into diverse effector T (Teff) cell types, remains controversial. Many Treg cells express T cell receptors (TCR) with heightened affinity for self-peptide MHC complexes (8–11) and ablation of a conditional Foxp3 allele in mature Treg cells results in generation of “former” Treg cells capable of causing inflammatory tissue lesions (12). Thus, the stability of Foxp3 expression under basal and inflammatory conditions is an important determinant of immune homeostasis and of immediate relevance to the question of whether Treg cells represent a distinct, stable cell lineage or a transient meta-stable activation state. Genetic fate mapping provides means to evaluate both lineage stability and informs mechanisms of tissue maintenance in vivo.

We used this approach to evaluate Treg cell lineage stability under basal and inflammatory conditions, and generated knock-in mice harboring a cassette containing an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) followed by DNA sequence encoding a “triple” fusion protein of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) with Cre recombinase and mutated human estrogen receptor ligand binding domain (ERT2) inserted into the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the Foxp3 gene.

The Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 mice were bred to mice that expressed a Cre recombination reporter allele of the ubiquitously expressed ROSA26 locus containing a loxP site-flanked STOP cassette followed by a DNA sequence encoding yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (R26Y) (fig. S1). In the Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice, the GFP-CreERT2 fusion protein is sequestered in the cytosol and, therefore, YFP is not expressed, but treatment with tamoxifen allows for nuclear translocation of the fusion protein, excision of the floxed STOP cassette, and constitutive and heritable expression of YFP in a cohort of cells that expressed Foxp3 at the time of tamoxifen administration. Importantly, in contrast to continuous labeling, inducible labeling of Foxp3 expressing cells with YFP avoids the constant incorporation into the labeled population of cells that transiently upregulate Foxp3 and affords assessment of bone fide Treg cell maintenance.

Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice had normal numbers of CD4 and CD8 double and single positive thymocytes and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the secondary lymphoid organs (fig. S2). Foxp3 and the associated eGFP reporter were expressed in a manner indistinguishable from expression of the Foxp3 protein in control wild-type mice and eGFP expression was limited to Foxp3+ cells (fig. S2, S3A). YFP was not detected in eGFP+ cells in the absence of tamoxifen, and was restricted to Foxp3+ cells upon tamoxifen administration (fig. S3, B and C). Treatment with tamoxifen resulted in three main populations of CD4+ T cells: eGFP−YFPFoxp3−“non-Treg” cells, eGFP+YFP− unlabeled Foxp3+ Treg cells and tagged eGFP+YFP+ Foxp3+ cells (fig. S4). In We also observed a minor population of eGFP−YFP+ cells (<5% of YFP+ cells), which may represent cells that were transiently expressing Foxp3 at the time of tamoxifen exposure. Importantly, both YFP-tagged and -untagged eGFP+ Treg cells expressed identical amounts of Foxp3 and all other Treg cell phenotypic and activation markers tested thus far (fig. S4, S5).

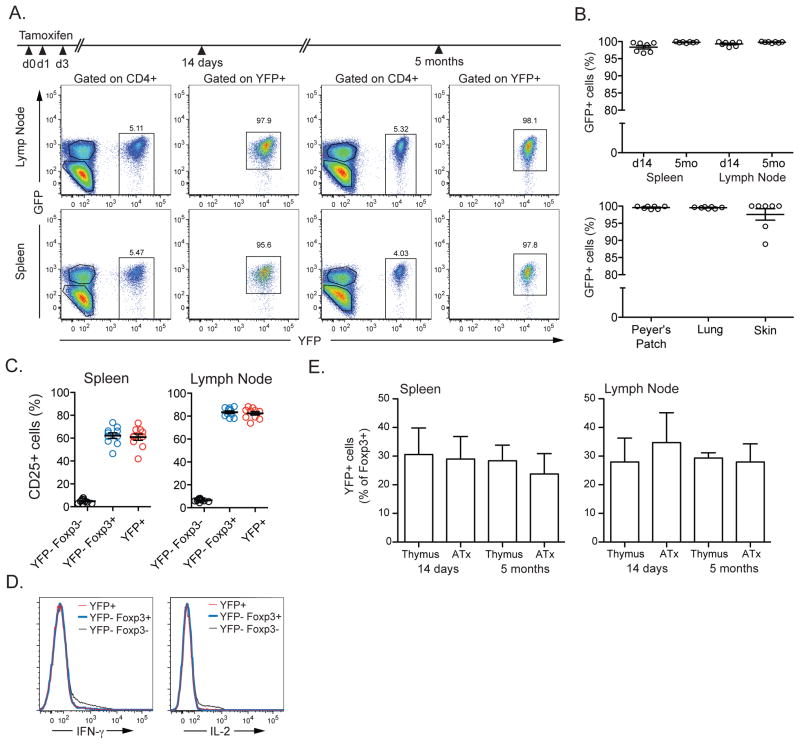

To evaluate long-term stability of Foxp3+ Treg cells under basal conditions Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice were treated with tamoxifen and analyzed 5–8 months later for Foxp3 expression in YFP+CD4+ T cells. The overwhelming majority of YFP+ CD4+ T cells remained eGFP positive in the lymph nodes, spleen, Peyer’s patches, skin and lung up to 5 months after tamoxifen treatment (Fig. 1A, B). This result was confirmed by intracellular staining for Foxp3 of FACS-purified YFP+ cells (fig. S6). Furthermore, expression of Treg cell-associated molecules was comparable between YFP+ and YFP+GFP+ cells (Fig. 1C and fig. S6) and production of proinflammatory cytokines was comparably low in both subsets (Fig. 1D). The minor population of eGFP−YFP+ cells observed 14 days after labeling failed to expand and in fact, further decreased over time (Figure 1C, D). Thus, we did not observe a noticeable “conversion” of Treg cells and their progeny into follicular T helper (TFH) or effector T cells or their de-differentiation into naïve T cells under physiologic conditions.

Fig. 1.

Inducible labeling of Foxp3+ cells reveals stability of Treg cell subset under physiologic conditions. (A) Representative flow-cytometric analyses demonstrate stability of Foxp3 expression at 14 days and 5 months after tamoxifen-induced labeling. YFP+, YFP−GFP+, and YFP−GFP-subsets of CD4+ T cells and proportion of GFP+ cells among YFP-tagged cells are shown. Numbers represent percentages of cells within the indicated gates. (B) Percentages of YFP+ cells expressing GFP in the indicated organs analyzed as in (A) at 5 months post tamoxifen administration (bottom). Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD25 expression in CD4+ cell subsets at 5 months post initial tamoxifen treatment. Expression of CD25 within the indicated subset is shown for individual mice. (D) Splenocytes from Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice were isolated 5 months after tamoxifen administration, stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in vitro and production of IFNγ and IL2 was assessed by flow-cytometry. Expression of IFNγ and IL2 in YFP+Foxp3+, YFP−Foxp3+, and YFP−Foxp3−subsets is shown. (E) Proportion of YFP-labeled cells among Foxp3+ cells in the periphery of thymectomized and non-thymectomized Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice at 14 days and 5 months post tamoxifen treatment. ATx: adult thymectomy. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n≥3 per group). Mice were 6–8 weeks of age at the time of labeling.

Surprisingly, in euthymic mice the proportion of YFP+ Treg cells among all Foxp3+ cells at 5–8 months post labeling was comparable to that observed at 14 days, despite continuous, albeit declining with age output of thymus-derived Treg cells (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, thymectomy failed to influence the proportion of YFP+ Treg cells among Foxp3+ cells at these later time points (Fig. 1E) suggesting that the peripheral Treg cell pool, which is characterized by a high proportion of cycling cells (fig. S7), is not only highly stable in adult mice, but is largely self-sustained with a relatively minor contribution by newly generated thymic emigrants.

We next asked whether Foxp3 can be lost upon growth factor deprivation as a validation of our Treg cell fate tracking approach. Foxp3 induction and Treg cell homeostasis are dependent upon interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor signaling (13–18) and antibody-mediated blockade of IL-2 or IL-2R causes contraction of the Treg cell population (15). Thus, we sought to explore whether IL-2 deprivation of mature Treg cells is associated with death or loss of Foxp3 expression and concomitant acquisition of immune effector cytokine production. Tamoxifen-treated Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice were treated with IL-2 neutralizing antibody. IL-2 deprivation resulted in a ~30% decrease in total Foxp3+ Treg cell numbers and a modest decrease in Foxp3 protein amounts at the single cell level (Fig. 2, A–C). Moreover, a small subset of YFP+ cells was completely devoid of Foxp3. We did not, however, observe de-repression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFNγ, IL-17, IL-2, and TNFα) by YFP+, YFP−GFP+ Treg cells with decreased Foxp3 levels or eGFP-YFP+ cells which had lost Foxp3 expression. These results demonstrate that upon IL-2 deprivation, the bulk of Treg cells maintained Foxp3 expression albeit at a moderately decreased level, yet sufficient to prevent acquisition of an effector cell phenotype. Nevertheless, it is possible that IL-2 deprivation under conditions of overwhelming infection might result in a loss of Foxp3 in some Treg cells (19).

Fig. 2.

IL-2 deprivation results in a small, but detectable decrease in Foxp3 expression. (A–C) Tamoxifen-treated Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice were injected with IL2 blocking antibody or control IgG and Foxp3 expression in FACS-sorted YFP+ cells was assessed 9 days later. (A) Intracellular Foxp3 staining of splenic YFP+ cells. Numbers represent percentages of cells in the indicated gate. (B) Percentages of YFP+ cells expressing Foxp3. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (C) Relative expression of Foxp3 in YFP+ cells from spleens of mice treated with IL2 blocking antibody. Data are representative of three independent experiments (n≥2 per group). Mice were 6–8 weeks of age at the time of antibody administration. (D–F) Treg cells maintain stable expression of Foxp3 under lymphopenic conditions. Lymphopenia was induced in tamoxifen treated Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice upon irradiation (600 rad) and mice were analyzed 14 days later. (D) Representative flow-cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression among cells isolated from spleens of control and irradiated mice 14 days post irradiation. Numbers represent percentages of cells in the indicated gate. (E) Percentages of GFP+ cells among YFP+ cells in spleens 14 days post irradiation. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (F) Representative flow-cytometric analysis of Foxp3 and Ki67 expression by YFP+ splenocytes on day 14 post-irradiation. Similar data were obtained from cells isolated from lymph nodes of irradiated mice. Data are representative ≥2 independent experiments, each with ≥2 mice per group. Mice were 8–12 weeks of age at the time of irradiation.

Lymphopenia may also facilitate loss of Foxp3 expression in expanding Treg cells. Despite utilization of purified Treg cells in previously published transfer studies, the possibility of outgrowth of a small number of contaminating non-Treg cells and stress associated with cell transfer remain potential caveats in interpretation of these results. To circumvent these issues, we used sublethal irradiation to evaluate stability of Foxp3 expression under lymphopenic conditions. Tamoxifen-treated Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice were irradiated (600 rad) and the proportion of eGFP+ and Foxp3+ cells among YFP+CD4+ T cells was evaluated 14 days post irradiation. Despite a marked increase in numbers of dividing Treg cells reflected in heightened expression of Ki67 in YFP+ and YFP−Treg cells, GFP and Foxp3 expression was preserved in YFP+ cells (Fig. 2, D–F). We considered that perturbation of the 3′UTR in Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice may have resulted in increased Foxp3 mRNA or protein stability. However, Foxp3 mRNA decay in the presence of actinomycin D in Treg cells from Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice was more pronounced than that in Treg cells from the previously described Foxp3GFP mice, in which GFP sequence was inserted into the 5′ end of the Foxp3 coding sequence leaving the 3′UTR intact (fig. S9) (4). To compare the stability of Foxp3 protein expression in Treg cells from Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice to that in Foxp3GFP mice in vivo, CD4+GFP+ cells were doubly purified by FACS from each mouse strain and co-transferred with Ly5.1+ CD4+ T cells into TCRβδ-deficient mice. Three weeks after transfer, the majority (~90%) of CD4+Ly5.2+ cells maintained GFP and Foxp3 protein expression and their percentages among cells transferred from both mouse strains were similar (fig. S10), further supporting the stability of the Treg cell lineage and indicating that the modification of the 3′UTR in Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26-YFP mice cannot account for this observation.

Previous studies suggested that during infection, exposure of Treg cells to pro-inflammatory cytokines results in a loss of Foxp3 expression and Treg cell conversion into effector T cells and were was interpreted as a means to facilitate appropriate immune responsiveness (20). To examine the fate of Foxp3+ Treg cells during infection, Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26-YFP mice were treated with tamoxifen, infected with a sub-lethal dose of Listeria monocytogenes and analyzed for Treg cell stability at the peak of the immune response. After infection, we observed considerable up-regulation of the T helper 1 transcription factor T-bet and CXCR3 in Foxp3−, Foxp3+ and YFP+ CD4+ cells (Fig. 3A, B and fig. S11) and IFNγ production by effector CD4+ T cells in response to listeriolysin O (LLO) peptide (Fig. 3C and fig. S11). Nevertheless, essentially all YFP+ Treg cells maintained expression of Foxp3 (Fig. 3D) including those with increased T-bet expression. Foxp3 stability was also observed in T-bet+Foxp3+ cells generated upon induction of a strong IFNγ dominated Th1 inflammatory response upon antibody-mediated cross-linking of CD40 (fig. S12) (21). Cross-linking of CD40 after tamoxifen-induced labeling resulted in a marked upregulation of T-bet and CXCR3 in Foxp3+ and Foxp3−cells (fig. S12). YFP tagged cells demonstrated increased expression of CXCR3 and T-bet, but at best marginally increased IFNγ and IL-2 production (fig. S12). Furthermore, Treg cells maintained expression of Foxp3 at 14 days and up to 5 months post CD40 cross-linking (fig. S12). Thus, Treg cells maintain heritable Foxp3 expression even after up-regulation of the Th1 transcription factor T-bet in the course Th1 dependent anti-bacterial infection and CD40 antibody driven Th1 inflammatory response. T-bet and CXCR3 induction in Treg cells was recently shown to facilitate their ability to restrain Th1 inflammation (21).

Fig. 3.

Th1 type inflammation does not induce loss of Foxp3. Tamoxifen treated Foxp3eGFP-Cre-ERT2 x R26Y mice were infected i.v. with 5 × 103 CFU of Listeria monocytogenes and analyzed 9 days later. (A) Flow-cytometric analysis demonstrates up-regulation of T-bet and CXCR3 by splenic YFP+ CD4+ cells in infected mice. (B) Percent of T-bet positive cells among Foxp3−−and YFP+ splenocytes as determined in (A). Each symbol represents an individual mouse. (C) Antigen specific production of IFNγ in splenocytes re-stimulated with LLO190-201 peptide. CD4+ T cell gate is shown; numbers represent percentages of cells in corresponding quadrants. (D) Foxp3 expression in sorted YFP−GFP+ (top) or YFP+ cells (bottom) from L. monocytogenes infected or control mice 9 days post infection. Data are representative of three independent experiments with ≥2 mice per group each. Mice were 6–8 weeks of age at the time of infection.

Lastly, to evaluate the stability of Foxp3+ cells in an autoimmune inflammatory setting, highly purified pancreatic-islet-antigen-specific GFP+ Treg cells from NOD.Foxp3gfp.BDC2.5 TCR-transgenic mice (22) were transferred into pre-diabetic, lymphoreplete NOD.Thy1.1 recipients at 12 weeks of age, a time point at which pancreatic infiltration is well established. Four weeks later, donor cells were enriched in the inflamed pancreas, but retained expression of Foxp3 and, in contrast to recipient effector cells, expressed no detectable IL-17 or IFNγ (Fig. 4, A–C). In parallel experiments, Treg cell stability was evaluated in the K/BxN TCR-transgenic model in which reactivity to a ubiquitous self-antigen leads IL-17- and gut microbiota-dependent generation of arthritogenic auto-antibodies (23). Highly purified GFP+ Treg cells from K/BxN.Foxp3gfp mice were transferred into 20-day-old K/BxN recipients, i.e. at the initiation of the very robust inflammatory process, and again remained almost exclusively Foxp3+, and failed to produce IL-17 in lymphoid organs or the lamina propria (Fig. 4, D–F). Thus, Treg cells maintained stable Foxp3 expression and showed no evidence of effector cytokine production under conditions of autoimmune inflammation.

Fig. 4.

Foxp3 expression is stable in Treg cells during autoimmune inflammation. (A–C) Highly purified GFP+ cells from BDC2.5.Foxp3eGFP mice were transferred into 12-week-old prediabetic NOD.Thy1.1 recipients, and the spleen, pancreatic lymph nodes (PLN) or pancreatic infiltrates were analyzed 4 weeks later. (A) Representative Foxp3 staining of Thy1.2+CD4+ donor cells. (B) Tabulation of individual mice in three independent experiments. (C) Intracellular IFNγ+ and IL-17+ staining of host and donor CD4+ cells (numbers represent percentage of cells in the gate ± SD; n=3–6 per group). (D–F) Highly purified CD4+GFP+ cells from 20 day-old K/BxN.Foxp3gfp mice were transferred into age-matched K/BxN.CD45.2 mice. (D) Spleen, joint-draining lymph node and small intestine lamina propria (LP) were collected from arthritic 35 day-old recipients and CD45.1+CD4+ donor cells analyzed for Foxp3-GFP expression. (E) Tabulation of individual mice in two independent experiments. (F) Expression of IL-17a by host and donor CD4+ cells from the lamina propria (numbers represent percentage of cells in the gate ± SD; n=3 per group). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

In contrast to our findings, a recent study reported a marked loss of Foxp3 expression in YFP-tagged Foxp3+ Treg cells in R26Y x Foxp3-Cre BAC transgenic mice and acquisition of effector function by YFP+Foxp3−T cells (24). Likewise, upon transfer into lymphopenic recipients Foxp3+ Treg cells were found to lose Foxp3 expression and differentiate into TFH cells in the Peyer’s patches (25). Seemingly unstable Foxp3 expression observed in these and other studies (see for review (20)) can be due to cellular stress, the presence of few contaminating Foxp3−cells or cells which underwent transient Foxp3 up-regulation, or recently generated Foxp3+ cells on their way to stable Foxp3 expression, yet still able to expand and differentiate into effector T cells in lymphopenic or non-lymphopenic settings. Consistent with the later notion, loss of Foxp3 expression by a minor population of YFP+ cells was observed during induction of Foxp3 in peripheral YFP−GFP−CD4+ T cells under lymphopenic conditions. In contrast, YFP+GFP+ Treg cells maintained Foxp3 expression in these experiments (fig. S13). Furthermore, transient expression of Foxp3 during RORγ dependent differentiation of Th17 cells was visualized through activation of the R26Y allele by Cre recombinase constitutively expressed under control of the endogenous Foxp3 locus (26). Additionally, differences in regulation of expression of Foxp3 BAC transgene and the endogenous Foxp3 locus encoding Cre can also affect the discrepant outcomes of YFP tagging of Treg cells in the corresponding experimental models.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the Treg cell lineage is remarkably stable under physiologic conditions and following a variety of challenges. Stable Foxp3 expression in committed Treg cells is likely facilitated by a positive autoregulatory loop (27). Our results also suggest that continuous self-renewal of the established Treg cell population combined with heritable maintenance of Foxp3 expression serves as a major mechanism of maintenance of this lineage in adult mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Forbush, T. Chu, L. Karpik, A. Bravo, J. Herlihy, P. Zarin, G. Gerard and A. Ortiz-Lopes and K. Hattori for assistance with mouse colony management; F. Costantini for R26Y mice; V. Kuchroo for Foxp3-IRES-GFP mice; P. Chambon for Cre-ERT2 plasmid; E. Pamer, C. Shi and E. Leiner for L. monocytogenes and assistance with experiments; and P. Fink and K. Simmons for cells from Rag2pGFP mice and helpful discussion. AYR is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Instituteand this work was also supported by grant AI51530 from the NIH to CB&DM.

References

- 1.el Marjou F, et al. Genesis. 2004 Jul;39:186. doi: 10.1002/gene.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA. Nature. 2004 May 6;429:41. doi: 10.1038/nature02520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Nature immunology. 2003 Apr 1;4:330. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontenot JD, et al. Immunity. 2005 Mar 1;22:329. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Adv Immunol. 2003 Jan 1;81:331. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(03)81008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. Nature immunology. 2003 Apr 1;4:337. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Nature immunology. 2007 Feb 1;8:191. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apostolou I, Sarukhan A, Klein L, von Boehmer H. Nature immunology. 2002 Aug 1;3:756. doi: 10.1038/ni816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh CS, et al. Immunity. 2004 Aug 1;21:267. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan MS, et al. Nature immunology. 2001 Apr 1;2:301. doi: 10.1038/86302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pacholczyk R, Ignatowicz H, Kraj P, Ignatowicz L. Immunity. 2006 Aug 1;25:249. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams LM, Rudensky AY. Nature immunology. 2007 Mar 1;8:277. doi: 10.1038/ni1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao W, et al. Nat Immunol. 2008 Nov;9:1288. doi: 10.1038/ni.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. J Immunol. 2007 Jan 1;178:280. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. J Exp Med. 2005 Mar 7;201:723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Nat Immunol. 2005 Nov;6:1142. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayer AL, Yu A, Malek TR. J Immunol. 2007 Apr 1;178:4062. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malek TR, et al. J Clin Immunol. 2008 Nov;28:635. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9235-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oldenhove G, et al. Immunity. 2009 Nov 20;31:772. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009 Jun;21:281. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch MA, et al. Nat Immunol. 2009 Jun;10:595. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz JD, Wang B, Haskins K, Benoist C, Mathis D. Cell. 1993 Sep 24;74:1089. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90730-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu HJ, et al. Immunity. Jun 25;32:815. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, et al. Nature immunology. 2009 Sep 1;10:1000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuji M, et al. Science. 2009 Mar 13;323:1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1169152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou L, et al. Nature. 2008 May 8;453:236. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Y, et al. Nature. 2010 Feb 11;463:808. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.