Abstract

Rice blast disease caused by Magnaporthe oryzae is one of the most serious diseases of cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) in most rice-growing regions of the world. In order to investigate early response genes in rice, we utilized the transcriptome analysis approach using a 300 K tilling microarray to rice leaves infected with compatible and incompatible M. oryzae strains. Prior to the microarray experiment, total RNA was validated by measuring the differential expression of rice defense-related marker genes (chitinase 2, barwin, PBZ1, and PR-10) by RT-PCR, and phytoalexins (sakuranetin and momilactone A) with HPLC. Microarray analysis revealed that 231 genes were up-regulated (>2 fold change, p < 0.05) in the incompatible interaction compared to the compatible one. Highly expressed genes were functionally characterized into metabolic processes and oxidation-reduction categories. The oxidative stress response was induced in both early and later infection stages. Biotic stress overview from MapMan analysis revealed that the phytohormone ethylene as well as signaling molecules jasmonic acid and salicylic acid is important for defense gene regulation. WRKY and Myb transcription factors were also involved in signal transduction processes. Additionally, receptor-like kinases were more likely associated with the defense response, and their expression patterns were validated by RT-PCR. Our results suggest that candidate genes, including receptor-like protein kinases, may play a key role in disease resistance against M. oryzae attack.

Keywords: defense response, Magnaporthe oryzae, MapMan analysis, rice, transcriptomics

Rice blast fungus (Magnaporthe oryzae), known as a hemi-biotrophic fungal pathogen, is the causative agent of rice blast disease (Couch et al., 2005; Talbot, 2003). After adhesion of spores onto the leaf surface, M. oryzae initiates germination of a germ tube within 2 h, forming a special infection-related structure called an ‘appressorium’ in the very early stages (2–20 h) of interaction (Ribot et al., 2008). Melanized appressoria can be generated by high pressure, which could help fungi to penetrate plant cell walls with high physical forces (Ribot et al., 2008). Initiation of an early interaction between rice and rice blast fungus starts in the penetration stage and lasts until the early biotrophic growth stage, which occurs within 48 hour post-inoculation (hpi).

Previous transcriptome studies by using microarrays or RNA-seq analysis have attempted to understand interaction between rice and rice blast fungus. Wei and colleagues employed microarray analysis to study transcriptome changes in compatible and incompatible rice cultivars at 24 hpi after rice blast fungus infection (Wei et al., 2013), suggesting that the transcriptional profiles of rice in compatible and incompatible interaction are mostly similar. The transcription factor gene WRKY47, which was identified in their study, was overexpressed in transgenic rice and resulted in increased resistance to rice blast fungus (Wei et al., 2013). In another similar RNA-seq experiment, gene ontology (GO) enrichment in compatible and incompatible interaction remained similar, whereas the genes sets contributing to each GOs were dissimilar (Bagnaresi et al., 2012). Moreover, in compatible interaction, genes related with phytoalexin biosynthesis, flavin-containing monooxygenase, chitinase, and glycosyl hydrolase 17 were dramatically up-regulated (Bagnaresi et al., 2012). More recently, an RNA-seq-based transcriptome analysis showed different transcriptional regulation in both rice and rice blast fungus (Kawahara et al., 2012). More drastic changes were observed in incompatible interaction compared with compatible one at 24 hpi in both rice and blast fungus in this stage. Further, several fungal genes encoding secreted effectors, which may be involved in the initial infection process, were up-regulated. These studies provided clues for understanding the rice immune response against rice blast fungus attack as well as how M. oryzae counters host defense.

Due to co-evolution processes, rice have developed molecular mechanisms to suppress successful infection by pathogens, such as recognition of pathogens through receptors, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), expression of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, and accumulation of anti-microbial secondary defense compounds, termed phytoalexins (Jwa et al., 2006). To recognize pathogen infection, plants contain a group of receptor-like kinases (RLK), which can bind with conserved microbe-associated molecular pattern (MAMP) ligands (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Interaction between receptors and MAMPs, such as FLS2 and flg22, trigger activation of kinase domains and signal transduction through phosphorylation (Chinchilla et al., 2007). In response to pathogen attack, ROSs are rapidly produced and transmitted to engage immune function, such as the hypersensitive response (Frederickson Matika and Loake, 2014). Meanwhile, ROS also play an important role in cell signaling and homeostasis. ROS-detoxifying enzymes are highly accumulated in the anti-pathogen infection process and help balance redox changes inside cells (Pang et al., 2011). PR genes are those genes that are involved in the plant defense response, and they function in suppressing pathogen infection, such as thaumatin-like proteins and chitinases (Sels et al., 2008). Overexpression of those defense related genes in plants has shown the ability to increase resistance to fungal infection (Datta et al., 1999; Iqbal et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2013). Therefore, transcriptome analysis of genes involved in the recognition of pathogen signaling as well as investigation of plant defense-related genes at early and late time points are both important for understanding plant immune responses to biotic stresses.

In this study, we performed a comparative transcriptome analysis of rice and rice blast fungus interaction in early and later interaction stages. Rice leaves infected with incompatible and compatible fungal strains at 12 and 48 hpi were used in our study. A total of 608 genes showed statistically significant changes in this process, and they were found to have multiple biological functions, such as cell signaling, redox states, and proteolysis. We also identified 18 genes encoding receptor-like kinases and validated them by RT-PCR, which showed good correlation with the microarray data. Our study is helpful for understanding rice-M. oryzae interaction, in both early and later stages of the infection.

Materials and Methods

Plant growth condition and pathogen inoculation

Fourth- to fifth-leaf-stage rice seedlings (Oryzae sativa cv. Jinheung) grown under natural light in a greenhouse (20–30°C) were used for inoculation of rice blast fungus. For fungal inoculation, a conidial suspension (1×105 conidia/mL) of M. oryzae race KJ401 and KJ301 (incompatible and compatible, respectively, to cv. Jinheung) was sprayed onto the leaves using an air sprayer. Inoculated plants were kept in a humidity chamber at 28°C and harvested at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi. For transcript profiling, leaf samples were collected at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi, were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from rice leaves (infected and corresponding control) using TRIzol RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and dissolved in ribonuclease-free water. Total RNA samples (5 μg per reaction) were reverse-transcribed using a cDNA synthesis system for RT-PCR according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Madison, WI, USA). RT-PCRs were performed according to the method reported earlier (Kim et al., 2009). Primers used for RT-PCR experiments are listed (Supplementary Table 1). Beta-actin, eEF1a, and OsUbi5 transcripts were used as an internal control to normalize not only the concentration of cDNA in each sample, but also the gene expression profile over the time course.

Measurement of phytoalexins

Infected rice leaves (100 mg) were extracted with 80% methanol by boiling for 5 min. Three microliters of the crude extract was then injected onto an HPLC and analyzed by LC-MS/MS according to previously reported conditions (Tamogami and Kodama, 2000). TSQ Quantum Ultra-MS/MS equipped with Accela 600 HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. MA, USA) and a reversed phase column (Waters Atlantis T3, 3 μm, 2.1×15 mm, flow rate of 0.2 ml/min with 80% aqueous methanol) was used. Sakuranetin and momilactone A were monitored at combinations of m/z 287/167 and m/z 315/271 in MRM (multiple reaction monitoring) modes by APCI (Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization) method according to the previous method with slight modifications (Tamogami and Kodama, 2000).

Microarray hybridization, data processing, and statistical analysis

The average size of probe was 60 nucleotides with its Tm value adjusted from 75 to 85°C. The microarray was manufactured at NimbleGen Inc (http://www.nimblegen.com/). Random GC probes (40,000) were used to monitor hybridization efficiency and four corners fiducial controls (225) were included to assist with overlaying the grid onto the image. Multiple analyses were performed with Limma package in R computing (Wettenhall and Smyth, 2004). The package adopts a linear modeling approach implemented by lmFit as well as empirical Bayes statistics implemented by eBayes. Genes showing significantly different expression were selected according to their log2 (Ratio) and p-value based on the following criteria: log2 (Ratio) > = 1 and p-value (differentially expressed) < 0.05. Multivariate statistical tests such as clustering, principal component analysis, and multidimensional scaling were performed with Acuity 3.1 (Axon Instruments). Hierarchical clustering was performed with similarity metrics based on squared Euclidean correlation, and average linkage clustering was used to calculate the distance of genes.

Standard procedures for statistical analysis (> 2-fold, p<0.05) were carried out using the statistical tool of the Microsoft Excel program. We next used the TIGR MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV, http://www.tm4.org/mev.html) to carry out clustering analyses and to generate heat-map expression patterns of the microarray data after mean scaling and log2 transformation.

MapMan analysis

The MapMan program, version 3.1.1, at the Max Plant Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology, Germany (Thimm et al., 2004) was also used for pathway analysis. Genes fold values were transformed to Log2 (fold), and then their means were calculated. These non-redundant genes were classified into MapMan BINs and their annotated functions were visualized using the MapMan program by searching against Oryza sativa TIGR5 database.

Results and Discussion

Validations of samples before transcriptome analysis

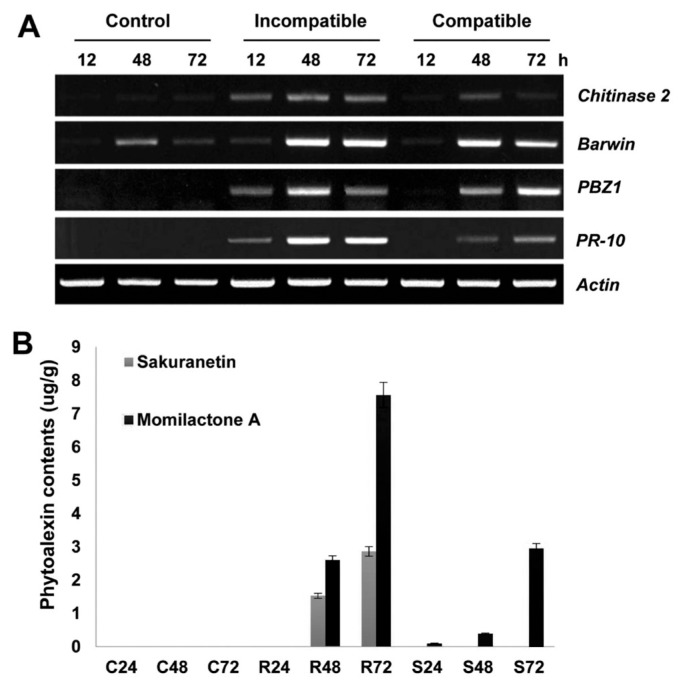

Genome wide microarray analysis provides a global view of gene regulation in response to particular biological events. To understand the differential transcriptional regulation of rice in response to rice blast fungus infection, we employed a 300 K tilling GeneChip in order to investigate RNA changes in the incompatible and compatible type fungal-infected rice leaves. Two different fungal stains, KJ401 and KJ301, which cause resistant and susceptible interactions in rice cv. Jinheung, respectively, were inoculated onto rice leaves. Leaf samples harvested at 12 and 48 hpi showed early induction and high accumulation of PR proteins (Kim et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2008). Prior to the microarray analysis, we validated M. oryzae-infected rice leaves using defense marker genes and phytoalexins (Fig. 1). Expression of rice PR marker genes was tested at 12, 48, and 72 hpi by RT-PCR. All of the tested PR genes, including chitinase 2, barwin, PBZ1, and PR-10, showed accumulation at 12 hpi in incompatible interaction and reached to a peak at 48 hpi (Fig. 1A). Transcriptional differences of these defense marker genes between the incompatible and compatible samples were conserved with previous transcriptome and/or proteome results (Kim et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2013). This result suggests that at early time points during rice-rice blast fungus interaction, plant defense-related genes are more rapidly and strongly activated in incompatible type interaction compared to compatible one.

Fig. 1.

Validation of samples used for the microarray experiment. (A) Expression profiles of defense marker genes in rice leaves infected with rice blast fungus at indicated time points. (B) Accumulation of phytoalexins, sakuranetin and momilactone A in fungal infected leaves were detected by HPLC.

Phytoalexin accumulation is another indication of activation of the plant immune response, and accumulation of phytoalexins was both delayed and reduced in incompatible interaction compared to incompatible one (Hasegawa et al., 2010; Jwa et al., 2006). Two phytoalexins, sakuranetin and momilactone A, were previously found to inhibit M. oryzae spore germination in M. oryzae-infected leaves (Hasegawa et al., 2010; Jwa et al., 2006; Kodama et al., 1992; Yamane, 2013). Here, the accumulation of sakuranetin and momilactone A was measured in M. oryzae-infected leaves using HPLC-MS/MS. Momilactone A was more highly accumulated in incompatible fungal-infected leaves compared to compatible one at 48 and 72 hpi (Fig. 1B). Sakuranetin was specifically accumulated in incompatible fungal-infected samples (Fig. 1B). Taken together, the expression of PR genes and accumulation of phytoalexins suggests that our samples can be used to investigate transcriptional regulation during rice and rice blast fungus interaction.

Investigating global changes in gene expression during incompatible and compatible rice-M. oryzae interaction

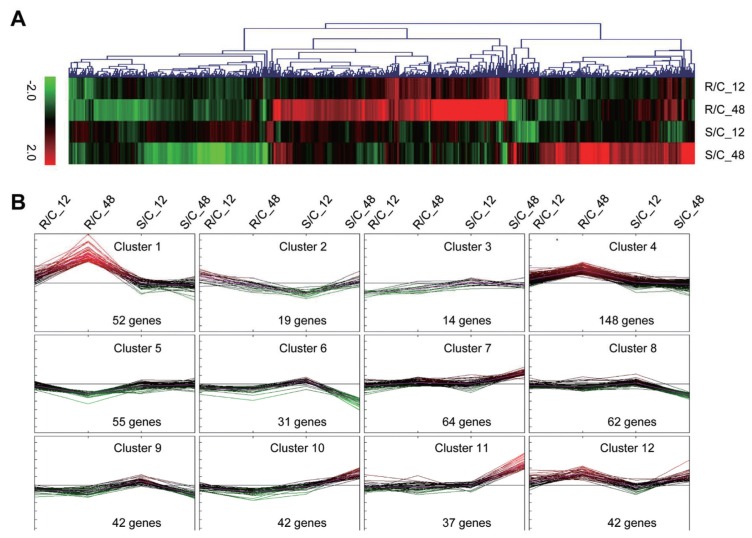

Differential transcriptional regulation of rice genes in response to fungal pathogen challenge was analyzed, and fold changes were calculated based on gene expression levels in incompatible and compatible type interactions compared with that of control. A total of 608 genes showed significantly increased expression (> 2-fold, p<0.05) in incompatible or compatible type interactions. A hierarchical clustering (HCL) analysis of all up-regulated genes was generated using multi-experimental viewer (MEV) software after loading log2 fold change values (Fig. 2A) (Cartwright et al., 1981). The expression patterns of incompatible and compatible interactions were different at each time point (Fig. 2A). Among those up-regulated genes, many genes showed increased expression at 12 hpi in incompatible interaction (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of rice transcriptome in response to incompatible (R) and compatible (S) blast fungus infection. (A) Hierarchical clustering and heat-map of gene expression in incompatible and compatible M. oryzae-infected leaf tissues at 12 and 48 hpi. (B) K-mean clustering analysis of gene expression profiles of 608 genes induced by M. oryzae. Acronyms stand for rice gene expression under the following conditions: R/C_12, incompatible sample at 12 hpi; R/C_48, incompatible sample at 48 hpi; S/C_12, compatible sample at 12 hpi; S/C_48, compatible sample at 48 hpi.

In a resistance interaction, plant immune signaling was triggered rapidly through the recognition of rice receptors by their elicitors/effectors, and PR genes were more rapidly accumulated in incompatible than in compatible interaction. Transcriptional expression analysis of PR genes also confirmed that an early defense response rapidly occurred in the incompatible interaction at 12 hpi, with high accumulation at 48 hpi (Fig. 1A). Therefore, characterization of rapidly or highly accumulated genes in incompatible type interaction is essential to understanding how rice responds to M. oryzae infection. Here, we classified those 608 regulated genes into 12 clusters according to their differential expression patterns through k-means clustering installed in MEV (Fig. 2B). Of them, 231 genes in clusters 1, 2, 4, and 12 showed higher accumulation in incompatible interaction than in compatible one (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

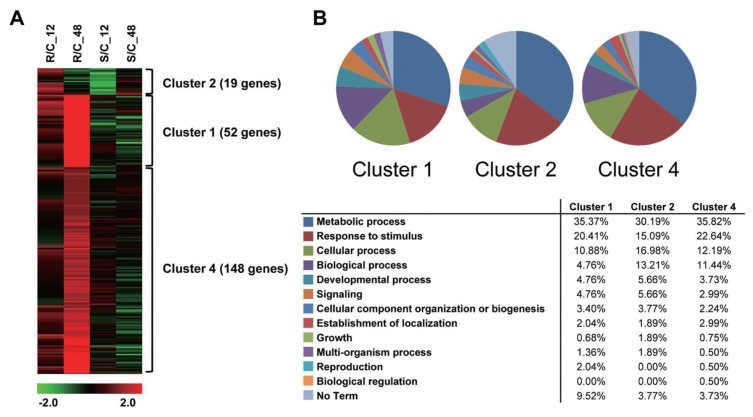

A heat-map of 231 genes associated with incompatible interaction was re-generated (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). As shown in the Fig. 3, clusters 1 and 4 were strongly associated with incompatible interaction at 48 hpi (R48) and contained 52 and 148 genes, respectively. The genes belonging to cluster 1 were much more strongly activated at R48 than those in cluster 4 (Fig. 3A). Nineteen genes belonged to cluster 2, which was highly up-regulated in incompatible interaction at 12 hpi and down-regulated in compatible interaction at 12 hpi.

Fig. 3.

Heat-Map and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of highly expressed genes in incompatible type interaction at 12 and 48 hpi. (A) Heat-Map of 261 highly induced genes, which were classified into four sub-groups based on their expression profiles by K-mean clustering analysis. (B) Number of enriched GO in four sub-groups.

Gene ontology analysis of rice genes associated with the incompatible interaction

To explore the biological processes associated with incompatible interaction, genes in clusters 1, 2, and 4 were grouped according to their gene ontology (GO) terms (http://www.gramene.org/), and the enriched GO terms (>two genes in each GO terms) were analyzed and summarized in Fig. 3B. GO analysis shows that the major GO term associated with incompatible interaction was metabolic process; 35.37%, 30.19%, and 35.83% genes in clusters 1, 2, and 4, respectively, suggesting that fungal infection may significant alter metabolic processes inside plants. Furthermore, genes related to the responses to stimuli, cell processes, biological processes, development, and signaling showed close association with incompatible interaction in each cluster (Fig. 3B). In the meantime, several genes related to cellular component organization or biogenesis and establishment of localization showed alteration during incompatible interaction. Genes related to biological regulation were only detected in cluster 4 (Fig. 3B). Taken together, our data suggest that rice reprograms metabolic and biological processes to initiate the response to infection by M. oryzae.

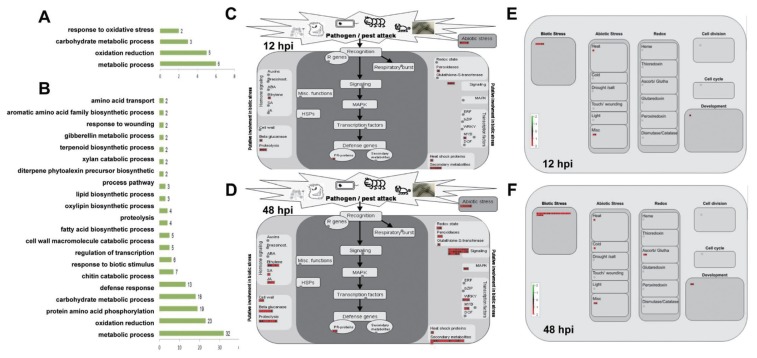

Further analysis of these transcriptome data showed that 41 of the 261 incompatible inducing genes were highly expressed at 12 hpi (Supplementary Table 2), whereas 231 were induced at 48 hpi (Supplementary Table 3). At 12 hpi, genes related with oxidative stress (two genes), carbohydrate metabolic processes (three genes), oxidation-reduction (five genes), and metabolic processes (six genes) were induced (Fig. 4A). At 48 hpi, genes related with carbohydrate metabolic processes (18 genes), oxidation-reduction (23 genes), and metabolic processes (32 genes) were still highly induced (Fig. 4B), suggesting that these cellular processes are essential for rice defense against M. oryzae. Moreover, other cellular processes showed involvement in rice defense at 48 hpi, such as protein amino acid phosphorylation (19 genes), defense response (13 genes), and biotic stimulus (six genes) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and MapMan analysis of up-regulated genes in incompatible type fungal infection. Number of enriched GO at 12 (A) and 48 hpi (B). Mapman analysis of up-regulated genes related with biotic stresses at 12 (C) and 48 hpi (D). Regulation overview (E and F) and cellular response overview (G and H) of up-regulated genes at 12 and 48 hpi.

MapMan analysis of rice genes associated with the incompatible interaction

To determine whether or not M. oryzae-induced genes are involved in multiple pathways, MapMan analysis (http://mapman.gabipd.org/) was applied to the characterized genes (Thimm et al., 2004). Based on the MapMan biotic stress analysis, the up-regulated genes were classified into different biological processes; three for signaling and one each for ethylene signaling, peroxidases, myb transcription factor, heat shock, and PR process at 12 hpi (Fig. 4C). At 48 hpi, the up-regulated genes related with biotic stresses showed significantly induction in multiple regulation pathways (Fig. 4D). For hormone signaling, five genes related with ethylene were detected, as well as genes related with salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) signaling. Previously, exogenous treatment with an ethylene (ET) biosynthesis inhibitor and generator was shown to suppress or induce infection by rice blast fungus in rice (Singh et al., 2004). Incompatible interaction with M. oryzae could also activate ET emissions earlier than compatible interaction (Iwai et al., 2006). Taken together, these results suggest that in early fungal infection, ethylene-related pathways may be important for rice innate immunity against rice blast fungus.

Genes related with the cell wall, beta-glucanase, and proteolysis were highly induced in response to M. oryzae infection (Fig. 4C and 4D). Cell wall structure and its related degradation enzymes are closely related with plant defense and fungal pathogenicity (Cantu et al., 2008). Overexpression of cell wall degradation enzymes such as Pectin Methylesterase 1 from Arabidopsis have been shown to reduce infection by Botrytis cinerae (Lionetti et al., 2007). Beta-glucanases, which digest the beta-1,3-glucan in fungal cell walls, directly inhibit fungal growth (Arlorio et al., 1992). Previous reports also indicated that several rice glucanses are induced in response to M. oryzae infection, suggesting that expression of glucanases is involved in the anti-fungal process (Bennett and Wallsgrove, 1994). Secondary metabolites, including terpenes, phenolics, nitrogen and sulfur-containing compounds, play important roles in plant defense against a variety of herbivores and pathogenic microorganisms (Jwa et al., 2006; Ross et al., 2007). Here, several genes related with secondary metabolism were up-regulated in response to M. oryzae infection, indicating that rice also utilizes secondary metabolites to suppress rice blast fungal infection.

WRKY transcription factors (TFs) are one of the largest families of transcriptional regulators in plants and have DNA-binding ability (Pandey and Somssich, 2009). A total of 109 WRKY TFs exist in rice, and they are related with the immunity response (Ross et al., 2007). In our results, WRKY genes were activated at 48 hpi in incompatible interaction (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Table 3). Previously, OsWRKY45, OsWAKY71, and OsWRKY76 were reported to be involved in M. oryzae attack, and OsWRKY45 and OsWRKY76 also activated by Xanthomonas oryzae infection (Ryu et al., 2006). Overexpression of OsWRKY45 also induces resistance to both M. oryzae and X. oryzae by mediating benzothiadiazole-inducible blast resistance, which is regulated by SA-dependent defense mechanisms (Shimono et al., 2007; 2012). OsWRKY71 is also induced by chitin oligosaccharide elicitor treatment, and over-expression of OsWRKY71 can trigger expression of defense-related genes, such as chitinase family genes. These data suggested that WRKY TFs are essential for defense mechanisms in the early interaction process. MAPK and Myb TFs are also involved in the activation of defense signaling in plants (Ramalingam et al., 2003; Rasmussen et al., 2012). At 48 hpi, several MAPK and Myb TFs as well as signaling-related genes were activated (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Table 3), suggesting that defense signaling-related genes are important to rice defense activation against rice blast fungus.

ROS levels are related with M. oryzae infection in rice leaf tissue (Chi et al., 2009; Mittler et al., 2004). Genes related with redox state, peroxidase, and glutathione-S-transferase were more up-regulated at 48 hpi than at 12 hpi (Fig. 4C and 4D, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3), suggesting elevation of ROS in infected tissues. Peroxidase is an ROS-related gene that plays a role in redox balance in cells (Mittler et al., 2004). In rice, peroxidase family genes are activated by infection by various pathogens, such as fungi and bacteria (Hilaire et al., 2001). Consistent with previous reports, two peroxidases were detected in our microarray results, suggesting that ROS signaling is activated in the early stage of M. oryzae infections.

A group of PR genes was detected in the microarray results, indicating that rice could rapidly sense M. oryzae infection and trigger its defense responses. The PR Bet v I protein family encoding PR-10 homolog genes is the most highly detected PR protein family (Radauer et al., 2008). One of them (PR Bet v I family protein, Os12g36850) was activated at 12 hpi, and six different genes were induced at 48 hpi (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). PR10 family proteins are activated in response to biotic as well as abiotic stresses (Kim et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2008). In response to M. oryzae infection, PR-10 family genes are differentially expressed in most tissues, such as root, leaf, stem, and flower (Kim et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2008; McGee et al., 2001).

Regulatory and cellular response overviews of those up-regulated genes at 12 hpi and 48 hpi were generated by MapMan analysis. Several genes related with protein degradation, modification, TFs, ethylene, receptor kinase, and nutrients were detected at 12 hpi, indicating that these processes were important for fungal sensing and/or resistance in early stages (Fig. 4C). Further analysis showed that those genes were also involved in biotic stress, abiotic stress (heat and miscellaneous functions), as well as development processes (Fig. 4E). Regulatory overview at 48 hpi showed that the number of genes with similar functions at 12 hpi increased. These results suggest that molecular process-related genes are essential for both early and later defense regulation in rice. In addition, several up-regulated genes were newly detected at 48 hpi, such as those related with JA and SA signaling, oxidation-reduction, calcium regulation, MAP kinase, and phosphoinositides (Fig. 4F). During rice defense against M. oryzae, JA and SA play an essential role in anti-fungal infection (Xie et al., 2011). ROS and calcium signaling are also essential for defense activation (Chi et al., 2009; Lecourieux et al., 2006; Mittler et al., 2004). These reports are consistent with our transcriptome results. For the cellular response overview, the number of up-regulated genes related with biotic stresses increased, and genes related with oxidation-reduction were newly detected (Fig. 4C and 4D). Taken together, our finding of up-regulated genes in response to M. oryzae infection provides an insight into rice-rice blast fungus interaction.

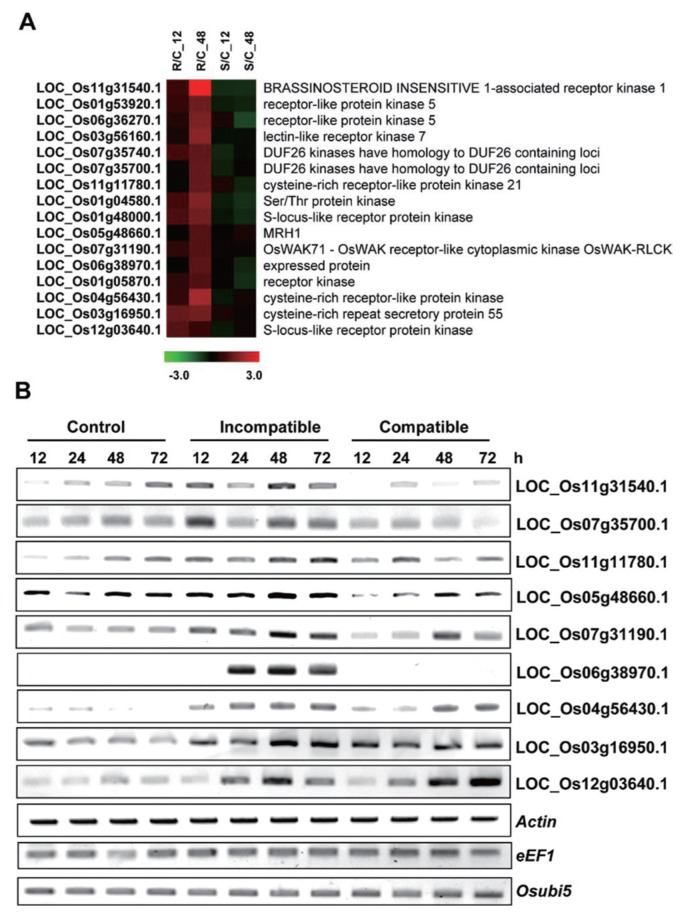

Receptor-like kinase genes induced by M. oryzae infection

Plant genomes encode a large number of RLKs involved in signal transduction during plant development and innate immunity (Greeff et al., 2012; Steinwand and Kieber, 2010). During defense, those RLKs recognize pathogen-associated signals and trigger a broad range of downstream defense responses (Jwa et al., 2006). Therefore, study of RLKs involved in defense signaling is essential for understanding host counterattack processes. Here, 18 rice RLKs showed significant up-regulation in incompatible interaction compared to compatible one (Fig. 5A), suggesting those RLKs may be essential for the rice anti-fungal process (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Up-regulation of receptor-like genes in incompatible type interaction. (A) Heat-map of receptor-like genes identified from microarray analysis. (B) Transcriptional expression of receptor-like genes in response to compatible and incompatible type fungal infections at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi were confirmed by RT-PCR.

Table 1.

List and expression levels of receptor like genes highly induced by rice blast fungus

| Cluster | Putative Function | Accession No. | R/C_12hpi | R/C_48hpi | S/C_12hpi | S/C_48hpi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brassinosteroid Insensitive 1-associated receptor kinase 1 | Os11g31540 | 0.811218 | 3.008376 | −0.48823 | −0.51775 |

| 12 | Receptor-like protein kinase | Os10g33040 | −0.02861 | 1.910698 | −0.34813 | 0.89525 |

| 4 | Receptor-like protein kinase 5 | Os01g53920 | 0.678137 | 1.419601 | −0.28261 | −0.36911 |

| 4 | Receptor-like protein kinase 5 | Os06g36270 | 0.448727 | 1.594526 | 0.319967 | −0.83046 |

| 4 | Lectin-like receptor kinase 7 | Os03g56160 | 0.320567 | 1.775792 | −0.1518 | −0.13174 |

| 4 | TKL_IRAK_DUF26-ld.2 - DUF26 kinases have homology to DUF26 containing loci | Os07g35740 | 0.884713 | 1.265413 | −0.40677 | −0.11206 |

| 4 | TKL_IRAK_DUF26-lc.4 - DUF26 kinases have homology to DUF26 containing loci | Os07g35700 | 0.158806 | 1.322579 | −0.31056 | −0.0296 |

| 4 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase 21 | Os11g11780 | −0.06805 | 1.32 | 0.384536 | −0.38594 |

| 4 | Ser/Thr protein kinase | Os01g04580 | 0.881316 | 1.673645 | −0.27655 | −0.54659 |

| 4 | S-locus-like receptor protein kinase | Os01g48000 | 0.978053 | 1.493597 | −0.20809 | −0.47656 |

| 4 | MRH1 | Os05g48660 | −0.05179 | 1.115766 | 0.010199 | 0.333886 |

| 4 | OsWAK71 - OsWAK receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase OsWAK-RLCK | Os07g31190 | 0.587842 | 1.076215 | 0.124959 | 0.165401 |

| 4 | Expressed protein | Os06g38970 | −0.00021 | 1.192931 | 0.072643 | −0.40049 |

| 4 | Receptor kinase | Os01g05870 | 0.582597 | 1.052183 | 0.045662 | −0.51644 |

| 4 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase | Os04g56430 | 0.62956 | 2.099881 | −0.2165 | 0.263735 |

| 4 | Cysteine-rich repeat secretory protein 55 | Os03g16950 | 1.324019 | 1.504747 | 0.321294 | 0.199844 |

| 4 | Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase 12 | Os04g30030 | −0.27925 | 1.126844 | 1.13936 | −0.16362 |

| 4 | S-locus-like receptor protein kinase | Os12g03640 | 1.108065 | 0.672518 | −0.23886 | 0.210872 |

Accession No., Accession number from KOME database (http://cdna01.dna.affrc.go.jp/cDNA/); R/C_12, log2 ratio of gene expression level in incompatible to control; S/C, log2 ratio of gene expression level in compatible to control.

A rice brassinosteroid insensitive 1-associated receptor kinase 1 (BAK1) showed specific expression in incompatible interaction at both 12 and 48 hpi (Fig. 5A). In Arabidopsis, BAK1 is a co-receptor of FLS2 and EFR, and it mediates pattern recognition receptor (PRR)-dependent signaling to initiate innate immunity (Jones and Dangl, 2006). These data suggested that rice BAK1 may also be related with recognition of PRR signaling from rice blast fungus to mediate activation of defense responses. Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase is also known to be involved in defense signal transduction in Arabidopsis (Ederli et al., 2011). DUF26 (Domain of Unknown Function 26) also belongs to the cysteine-rich RLK (CRK) family. DUF26 has been suggested to play an important role in defense against pathogen infection. Overexpression of CRKs could enhance plant resistance to pathogen infection by triggering hypersensitive responses (Acharya et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004). In rice, DUF26 protein is highly enriched in the apoplastic region in response to infection by M. oryzae and X. oryzae (Kim et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2013), indicating that the DUF26 gene is involved in pathogen resistance in rice. In our study, six CRKs, including two DUF26 kinases, were induced in the incompatible responses (Fig. 5A), indicating that activation of those genes are involved in resistance to rice blast fungus infection.

The plasma membrane localized wall-associated kinase (WAK) family of proteins is tightly bound to plant cell walls (He et al., 1996), WAK proteins have the ability to recognize oligogalacturonides released from the cell wall during pathogen infection, known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and trigger innate immune responses (Brutus et al., 2010). Overexpression of WAK1 in Arabidopsis leads to increased resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea. In rice, overexpression of OsWAK1 increases resistance to M. oryzae infection. Here, OsWAKY71 was highly accumulated in response to incompatible type fungal infection (Fig. 5A). These data suggest that OsWAK71 may play a role in anti-fungal infection through DAMP-triggered immunity.

Two TKL (tyrosine kinase-like)-IRAK (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase) type RLKs were also induced by incompatible type interaction (Fig. 5A). TKL-IRAK-type RLKs constitute a conserved protein family that is present in both animal and plants, and they are related with development, stress, symbiosis, as well as innate immunity (Dardick and Ronald, 2006). TKL-IRAK RLKs are also related with PRR-mediated defense signaling in plants, such as rice XA21 and Arabidopsis FLS2 (Dardick and Ronald, 2006; Dunning et al., 2007). Taken together, our transcriptome results indicate that the RLKs highly detected in incompatible interaction may be involved in the recognition of fungal elicitors/effectors to trigger host immune responses.

To further verify these results, semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was carried out on six identified RLKs (Fig. 5B). Rice actin, eEF1, and Osubi5 were employed as internal standards (Fig. 5B). Eight RLK genes were selected to confirm transcriptional expression in compatible and incompatible type interactions at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi. Compared with their expression levels in uninfected (control) and compatible type fungal-infected leaves, all of the genes were highly expressed in incompatible type interaction (Fig. 5), indicating good correlation with our transcriptome data. Further functional analyses of these candidate genes are required for the development of rice plants with enhanced defense responses against rice blast fungus infection.

Conclusions

In this study, we performed transcriptome analysis using a microarray to study the responses of rice cells in the early stage of M. oryzae infection. A total number of 608 genes were differentially expressed in response to compatible and incompatible type M. oryzae infections. Among them, 231 genes were more highly accumulated in incompatible type interaction compared to compatible one, indicating those genes play a major role in the response against fungal infection. Most of those genes functioned in the metabolic process, response to stimuli, and cellular processes, indicating these processes are strongly altered by fungal infection. The biotic stress map view of MapMan analysis showed that genes related with signaling (WRKY and Myb transcription factors) and secondary metabolism were rapidly induced, and ethylene was important for the defense response. Moreover, a total of 18 receptor-like protein kinase genes were identified in our results, and their expression was validated by RT-PCR analysis. Thus, RLK genes may be essential for the sensing of pathogen signals and induction of immunity in rice against rice blast fungus infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2013R1A1A1A05005407), and Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (Plant Molecular Breeding Center, PJ008021), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- Acharya BR, Raina S, Maqbool SB, Jagadeeswaran G, Mosher SL, Appel HM, Schultz JC, Klessig DF, Raina R. Overexpression of CRK13, an Arabidopsis cysteine-rich receptor-like kinase, results in enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas syringae. Plant J. 2007;50:488–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlorio M, Ludwig A, Boller T, Bonfante P. Inhibition of fungal growth by plant chitinases and β-1,3-glucanases. Protoplasma. 1992;171:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnaresi P, Biselli C, Orru L, Urso S, Crispino L, Abbruscato P, Piffanelli P, Lupotto E, Cattivelli L, Vale G. Comparative transcriptome profiling of the early response to Magnaporthe oryzae in durable resistant vs susceptible rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RN, Wallsgrove RM. Secondary metabolites in plant defence mechanisms. New Phytol. 1994;127:617–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb02968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutus A, Sicilia F, Macone A, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. A domain swap approach reveals a role of the plant wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) as a receptor of oligogalacturonides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:9452–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000675107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantu D, Vicente AR, Labavitch JM, Bennett AB, Powell AL. Strangers in the matrix: Plant cell walls and pathogen susceptibility. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright DW, Langcake P, Pryce RJ, Leworthy DP, Ride JP. Isolation and characterization of two phytoalexins from rice as momilactones A and B. Phytochemistry. 1981;20:535–537. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Du L, Chen Z. Sensitization of defense responses and activation of programmed cell death by a pathogen-induced receptor-like protein kinase in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;53:61–74. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000009265.72567.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Fan B, Du L, Chen Z. Activation of hypersensitive cell death by pathogen-induced receptor-like protein kinases from arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;56:271–283. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-3381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi MH, Park SY, Kim S, Lee YH. A novel pathogenicity gene is required in the rice blast fungus to suppress the basal defenses of the host. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000401. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D, Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Kemmerling B, Nurnberger T, Jones JD, Felix G, Boller T. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature. 2007;448:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch BC, Fudal I, Lebrun MH, Tharreau D, Valent B, van Kim P, Notteghem JL, Kohn LM. Origins of host-specific populations of the blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae in crop domestication with subsequent expansion of pandemic clones on rice and weeds of rice. Genetics. 2005;170:613–630. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.041780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardick C, Ronald P. Plant and animal pathogen recognition receptors signal through non-RD kinases. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta K, Velazhahan R, Oliva N, Ona I, Mew T, Khush GS, Muthukrishnan S, Datta SK. Over-expression of the cloned rice thaumatin-like protein (PR-5) gene in transgenic rice plants enhances environmental friendly resistance to rhizoctonia solani causing sheath blight disease. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98:1138–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning FM, Sun W, Jansen KL, Helft L, Bent AF. Identification and mutational analysis of Arabidopsis FLS2 leucine-rich repeat domain residues that contribute to flagellin perception. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3297–3313. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ederli L, Madeo L, Calderini O, Gehring C, Moretti C, Buonaurio R, Paolocci F, Pasqualini S. The Arabidopsis thaliana cysteine-rich receptor-like kinase CRK20 modulates host responses to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 infection. J Plant Physiol. 2011;168:1784–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson Matika DE, Loake GJ. Redox regulation in plant immune function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeff C, Roux M, Mundy J, Petersen M. Receptor-like kinase complexes in plant innate immunity. Front PlantSci. 2012;3:209. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Mitsuhara I, Seo S, Imai T, Koga J, Okada K, Yamane H, Ohashi Y. Phytoalexin accumulation in the interaction between rice and the blast fungus. MolPlant-Microbe Interact. 2010;23:1000–1011. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-8-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ZH, Fujiki M, Kohorn BD. A cell wall-associated, receptor-like protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19789–19793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilaire E, Young SA, Willard LH, McGee JD, Sweat T, Chittoor JM, Guikema JA, Leach JE. Vascular defense responses in rice: Peroxidase accumulation in xylem parenchyma cells and xylem wall thickening. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2001;14:1411–1419. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.12.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal MM, Nazir F, Ali S, Asif MA, Zafar Y, Iqbal J, Ali GM. Over expression of rice chitinase gene in transgenic peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) improves resistance against leaf spot. Mol Biotechnol. 2012;50:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s12033-011-9426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai T, Miyasaka A, Seo S, Ohashi Y. Contribution of ethylene biosynthesis for resistance to blast fungus infection in young rice plants. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1202–1215. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jwa NS, Agrawal GK, Tamogami S, Yonekura M, Han O, Iwahashi H, Rakwal R. Role of defense/stress-related marker genes, proteins and secondary metabolites in defining rice self-defense mechanisms. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006;44:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y, Oono Y, Kanamori H, Matsumoto T, Itoh T, Minami E. Simultaneous RNA-seq analysis of a mixed transcriptome of rice and blast fungus interaction. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Wang Y, Lee KH, Park ZY, Park J, Wu J, Kwon SJ, Lee YH, Agrawal GK, Rakwal R, Kim ST, Kang KY. In-depth insight into in vivo apoplastic secretome of rice-Magnaporthe oryzae interaction. J. Proteomics. 2013;78:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Kim SG, Hwang DH, Kang SY, Kim HJ, Lee BH, Lee JJ, Kang KY. Proteomic analysis of pathogen-responsive proteins from rice leaves induced by rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe grisea. Proteomics. 2004;4:3569–3578. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Yu S, Kang YH, Kim SG, Kim JY, Kim SH, Kang KY. The rice pathogen-related protein 10 (JIOsPR10) is induced by abiotic and biotic stresses and exhibits ribonuclease activity. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:593–603. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0485-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Kang YH, Wang Y, Wu J, Park ZY, Rakwal R, Agrawal GK, Lee SY, Kang KY. Secretome analysis of differentially induced proteins in rice suspension-cultured cells triggered by rice blast fungus and elicitor. Proteomics. 2009;9:1302–1313. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama O, Miyakawa J, Akatsuka T, Kiyosawa S. Sakuranetin, a flavanone phytoalexin from ultraviolet-irradiated rice leaves. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3807–3809. [Google Scholar]

- Lecourieux D, Ranjeva R, Pugin A. Calcium in plant defence-signalling pathways. New Phytol. 2006;171:249–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti V, Raiola A, Camardella L, Giovane A, Obel N, Pauly M, Favaron F, Cervone F, Bellincampi D. Overexpression of pectin methylesterase inhibitors in Arabidopsis restricts fungal infection by Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1871–1880. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.090803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee JD, Hamer JE, Hodges TK. Characterization of a PR-10 pathogenesis-related gene family induced in rice during infection with Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2001;14:877–886. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.7.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Gollery M, Van Breusegem F. Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SP, Somssich IE. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1648–1655. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang CH, Li K, Wang B. Overexpression of SsCHLAPXs confers protection against oxidative stress induced by high light in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. PhysiolPlant. 2011;143:355–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radauer C, Lackner P, Breiteneder H. The bet v 1 fold: An ancient, versatile scaffold for binding of large, hydrophobic ligands. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:286. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam J, Vera Cruz CM, Kukreja K, Chittoor JM, Wu JL, Lee SW, Baraoidan M, George ML, Cohen MB, Hulbert SH, Leach JE, Leung H. Candidate defense genes from rice, barley, and maize and their association with qualitative and quantitative resistance in rice. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2003;16:14–24. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen MW, Roux M, Petersen M, Mundy J. MAP kinase cascades in Arabidopsis innate immunity. FrontPlant Sci. 2012;3:169. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribot C, Hirsch J, Balzergue S, Tharreau D, Notteghem JL, Lebrun MH, Morel JB. Susceptibility of rice to the blast fungus, Magnaporthe grisea. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Liu Y, Shen QJ. The WRKY gene family in rice (Oryza sativa) J Integr Plant Biol. 2007;49:827–842. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu HS, Han M, Lee SK, Cho JI, Ryoo N, Heu S, Lee YH, Bhoo SH, Wang GL, Hahn TR, Jeon JS. A comprehensive expression analysis of the WRKY gene superfamily in rice plants during defense response. Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25:836–847. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sels J, Mathys J, De Coninck BM, Cammue BP, De Bolle MF. Plant pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins: A focus on PR peptides. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46:941–950. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono M, Koga H, Akagi A, Hayashi N, Goto S, Sawada M, Kurihara T, Matsushita A, Sugano S, Jiang CJ, Kaku H, Inoue H, Takatsuji H. Rice WRKY45 plays important roles in fungal and bacterial disease resistance. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13:83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono M, Sugano S, Nakayama A, Jiang CJ, Ono K, Toki S, Takatsuji H. Rice WRKY45 plays a crucial role in benzothiadiazole-inducible blast resistance. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2064–2076. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MP, Lee FN, Counce PA, Gibbons JH. Mediation of partial resistance to rice blast through anaerobic induction of ethylene. Phytopathology. 2004;94:819–825. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.8.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinwand BJ, Kieber JJ. The role of receptor-like kinases in regulating cell wall function. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:479–484. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot NJ. On the trail of a cereal killer: Exploring the biology of Magnaporthe grisea. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:177–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamogami S, Kodama O. Coronatine elicits phytoalexin production in rice leaves (Oryza sativa L.) in the same manner as jasmonic acid. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:689–694. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm O, Blasing O, Gibon Y, Nagel A, Meyer S, Kruger P, Selbig J, Muller LA, Rhee SY, Stitt M. MAPMAN: A user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant J. 2004;37:914–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kim SG, Wu J, Huh HH, Lee SJ, Rakwal R, Agrawal GK, Park ZY, Kang KY, Kim ST. Secretome analysis of the rice bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae (Xoo) using in vitro and in planta systems. Proteomics. 2013;13:1901–1912. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei T, Ou B, Li J, Zhao Y, Guo D, Zhu Y, Chen Z, Gu H, Li C, Qin G, Qu LJ. Transcriptional profiling of rice early response to Magnaporthe oryzae identified OsWRKYs as important regulators in rice blast resistance. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettenhall JM, Smyth GK. limmaGUI: A graphical user interface for linear modeling of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3705–3706. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Wang Y, Kim ST, Kim SG, Kang KY. Characterization of a newly identified rice chitinase-like protein (OsCLP) homologous to xylanase inhibitor. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie XZ, Xue YJ, Zhou JJ, Zhang B, Chang H, Takano M. Phytochromes regulate SA and JA signaling pathways in rice and are required for developmentally controlled resistance to Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Plant. 2011;4:688–696. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane H. Biosynthesis of phytoalexins and regulatory mechanisms of it in rice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:1141–1148. doi: 10.1271/bbb.130109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CJ, Wang AR, Shi YJ, Wang LQ, Liu WD, Wang ZH, Lu GD. Identification of defense-related genes in rice responding to challenge by Rhizoctonia solani. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;116:501–516. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0686-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]