Abstract

Genomes contain a large number of unique genes which have not been found in other species. Although the origin of such “orphan” genes remains unclear, they are thought to be involved in species-specific adaptive processes. Here, we analyzed seven orphan genes (MoSPC1 to MoSPC7) prioritized based on in planta expressed sequence tag data in the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. Expression analysis using qRT-PCR confirmed the expression of four genes (MoSPC1, MoSPC2, MoSPC3 and MoSPC7) during plant infection. However, individual deletion mutants of these four genes did not differ from the wild-type strain for all phenotypes examined, including pathogenicity. The length, GC contents, codon adaptation index and expression during mycelial growth of the four genes suggest that these genes formed during the evolutionary history of M. oryzae. Synteny analyses using closely related fungal species corroborated the notion that these genes evolved de novo in the M. oryzae genome. In this report, we discuss our inability to detect phenotypic changes in the four deletion mutants. Based on these results, the four orphan genes may be products of de novo gene birth processes, and their adaptive potential is in the course of being tested for retention or extinction through natural selection.

Keywords: fungal pathogenesis, gene birth, Magnaporthe oryzae, orphan gene

Orphan genes are protein-coding regions that lack any recognizable orthologs in other organisms (Ekman and Elofsson, 2010). Based on the large number of genome sequences available, orphans are a universal feature of all genomes (Khalturin et al., 2009). Two major models have been proposed for the origin of new genes; the duplication-divergence model and de novo evolution model (Tautz and Domazet-Loso, 2011). In the first model, new genes emerge through gene duplication followed by rapid divergence leading to loss of similarity to the gene from which it was duplicated (Domazet-Loso and Tautz, 2003). This model has been well-supported and is considered the major mechanism for creating evolutionary novelties. However, within the framework of this model, it is difficult to explain how natural selection can choose one gene for divergence while retaining the duplicate to maintain the ancestral function (Conant and Wolfe, 2008; Lynch and Katju, 2004). Furthermore, this model is based on the extensive accumulation of substitutions over the entire length of the protein during divergence to the point at which paralogous relationships cannot be detected. This assumption rarely holds due to the existence of functional protein domains in many genes. The second model postulates that a new gene can emerge directly from non-coding sequences via a random combination of sequences, giving rise to functional sites such as transcription initiation regions and polyadenylation sites (Siepel, 2009).

Although such de novo gene birth is considered very rare, recent reports provided evidence for this type of gene birth in a variety of organisms (Begun et al., 2007; Cai et al., 2008; Donoghue et al., 2011; Heinen et al., 2009; Levine et al., 2006; Li et al., 2010a; Yang and Huang, 2011; Zhou et al., 2008). Furthermore, comparative analyses of genome sequences revealed that orphan genes emerge at high rates and account for 10–20% of total genes within individual eukaryotic genomes (Domazet-Loso and Tautz, 2003; Khalturin et al., 2009). Characteristics of orphan genes are well-documented in diverse eukaryotes. They are relatively short (both with respect to gene and ORF length), contain a low number of exons and the detectable domains and are less expressed and evolve more rapidly than non-orphan or old genes (Carvunis et al., 2012; Neme and Tautz, 2013).

Orphan genes are believed to be involved in species-specific processes of adaptation (Kaessmann, 2010). A number of studies provide examples supporting such roles of orphan genes. In human, FLJ33706 that encodes newly organized genes is associated with brain function (Li et al., 2010a). In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the newly born BSC4 gene is suggested to be involved in the DNA damage repair pathway during the stationary phase, whereas another new gene, MDF1, promotes vegetative growth and decreases mating efficiency in rich media (Cai et al., 2008; Li et al., 2010b). The EED1 gene, which is found only in Candida albicans, is crucial for hyphal extension and maintenance of filamentous growth both on solid surfaces and during the interaction with host cells (Martin et al., 2011).

In this report, we analyzed orphan genes and determined whether they are involved in fungal pathogenesis in a model plant pathogenic fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. The fungus is a causal agent of the rice blast disease, which is one of the most devastating global fungal diseases of cultivated rice (Talbot, 2003; Valent and Chumley, 1991). Leaf infection by this fungus is initiated by landing of a conidium on the leaf surface. Melanized appressorium develops to mechanically penetrate the cuticular layer, following conidial germination (Wilson and Talbot, 2009). Rice blast is used as a model system to investigate host-pathogen interactions due to the genetic tractability and availability of genome sequences for both organisms (Dean et al., 2005; Goff, 2005; Yu et al., 2002). In this study, we report for the first time the identification and analysis of orphan genes in M. oryzae.

Materials and Methods

Computational analysis

Orphan genes were identified using BLASTP searches against the NCBI non-redundant dataset using protein sequences of M. oryzae as queries. The E-value threshold was set at 10−3. The BLAST matrix function embedded in CFGP 2.0 was used to visualize the presence of the gene in M. oryzae among species with genome sequences archived in CFGP 2.0 (Choi et al., 2013) (http://cfgp.snu.ac.kr/). Comparison between orphan and non-orphan genes based on gene length, GC content, transcript abundance, and codon adaptation index was performed using R (http://www.R-project.org/).

Fungal isolates and culture conditions

Magnaporthe oryzae strain KJ201 was provided by the Center for Fungal Genetic Resources (CFGR, http://genebank.snu.ac.kr) and was used as the wild-type strain for this study. All strains including mutants were grown on V8 agar [V8; 8% V8 juice (v/v) and 1.5% agar (w/v), adjusted to pH 6.0 using NaOH] or oatmeal agar [OMA; 5% oatmeal (w/v) and 2% agar (w/v)] at 25°C in constant light to promote conidial production (Park et al., 2010). For conidial production, strains were cultured on V8 juice agar medium for 7 days or on OMA for 10 to 15 days at 25°C under continuous light conditions. To compare mycelial growth, modified complete agar medium (MCA) or modified minimal agar medium (MMA) (Talbot et al., 1993) was used.

Nucleic acid manipulation and expression analysis

Two methods were used for fungal genomic DNA isolation based on two different purposes. A quick and easy genomic DNA extraction method was used for PCR-based screening of transformants (Chi et al., 2009). Genomic DNA was isolated from mycelia according to a standard protocol for southern hybridization (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). Southern DNA hybridization was performed with the selected transformants to ensure correct gene replacement events and absence of ectopic integration. Genomic DNA was digested with BamHI, PstI, XhoI and NheI, and blots were probed with 1-kb 5′-flanking or 3′-flanking sequences (Fig. S1). Southern DNA hybridization was performed using a standard method (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). To perform expression analysis using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), cDNA synthesis was performed with 5 μg of total RNA using the oligo dT primer with the ImProm-IITM Reverse Transcription System kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer pairs used in this study were listed in Table S1.

Targeted gene deletion

Knock-out constructs of individual genes were generated by double-joint PCR where ~1 kb flanking sequences of each gene was amplified and fused with the hygromycin resistance gene (HPH) cassette. The knock-out constructs were transferred to wild-type protoplasts and the resulting transformants were primarily selected by PCR-based screening using specific primer pairs MoSPC1_NF, MoSPC1_NR, MoSPC2_NF, MoSPC2_NR, MoSPC3_NF, MoSPC3_NR, MoSPC7_NF and MoSPC7_NR (Table S1). Knock-outs were confirmed by Southern blot analysis using one of the flanking sequences as a probe.

Developmental phenotype assays

Radial mycelial growth was measured on modified complete agar medium (MCA) or modified minimal agar medium (MMA) 12 days after inoculation (DAI) with three replications (Kim et al., 2014). Conidia were harvested from 7-day-old mycelia grown on V8 juice agar plates and the conidial suspension was adjusted to 2×104 conidia/ml. For conidial germination and appressorium formation, 40 μl of conidial suspension was dropped onto plastic coverslips with three replicates and incubated in a moistened box at room temperature. At 2 and 4 h after incubation, the frequency of conidial germination was determined by counting at least 100 conidia per replicate under a microscope. The frequency of appressorium formation was measured from germinated conidia at 8 h after incubation. Conidiation was determined by counting the number of conidia using a hemacytometer under a microscope. These assay processes were performed with three replicates in three independent experiments.

Pathogenicity assay

For the pathogenicity assay by spray inoculation, conidia were collected from 7-day-old V8 juice agar medium and 10 ml of conidial suspension were adjusted to 1×105 conidia/ml containing Tween 20 (250 ppm final concentration) and sprayed onto the rice seedlings (Oryza sativa cv. Nakdongbyeo) of three to four leaf stages. Sprayed rice seedlings were placed in a dew chamber for 24 h under dark conditions at 25°C, then transferred to a rice growth incubator at 25°C, 80% humidity and a 16-h photoperiod with fluorescent lights.

Results

Identification of orphan genes with transcriptional activity in M. oryzae

To identify orphan genes in the M. oryzae genome, we performed BLASTP searches against the NCBI non-redundant database (NCBI nr) with an e-value threshold of 10−3. This search demonstrated that 2,740 out of 12,991 genes (~21%) encode putative proteins with no match in the NCBI nr, indicating that they are likely orphan genes. We hypothesized that there should be evidence of transcription of orphan genes with roles in the host plant interaction. Thus, we utilized a previously reported in planta EST library (Kim et al., 2010). Although a total of 712 genes were initially reported to have in planta ESTs, we found only 542 genes in M. oryzae genome version 8. Comparison of orphan genes and in planta EST data showed that seven genes were shared between the two datasets. Since these genes were specific to M. oryzae, we named them MoSPCs (Magnaporthe oryzae specific). These genes were typically less than 1 kb in length (excluding MoSPC6), and MoSPC3 was predicted to contain a signal peptide (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structural characteristics of MoSPC genes

| Gene name | Gene size (bp) | No. of exons | Longer exon (bp) | Secretion possibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoSPC1 | 809 | 3 | 330 | No |

| MoSPC2 | 546 | 2 | 251 | No |

| MoSPC3 | 704 | 3 | 198 | Yes |

| MoSPC4 | 233 | 2 | 134 | No |

| MoSPC5 | 984 | 1 | 298 | No |

| MoSPC6 | 1979 | 7 | 218 | No |

| MoSPC7 | 777 | 2 | 222 | No |

Expression analysis of in planta expressed M. oryzae orphan genes

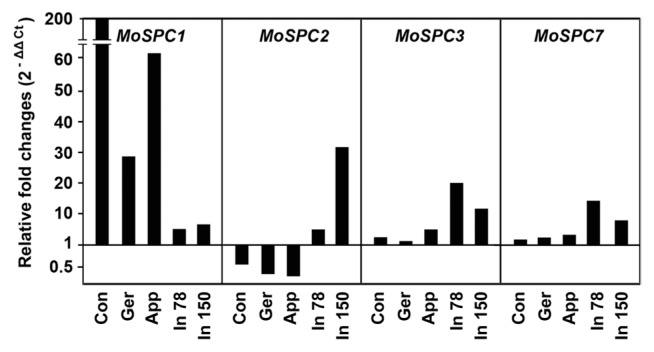

The presence of expressed sequence tag (EST)s is a good indication of transcriptional activity. However, it does not provide information on differential expression of a gene, which is associated with the gene’s role. Therefore, we examined the transcriptional activity of seven genes during different developmental stages, including plant infection, using qRT-PCR. Expression profiling suggested that four genes (MoSPC1, MoSPC2, MoSPC3 and MoSPC7) among the seven are differentially expressed during plant infection (appressorium formation and invasive growth) compared to mycelial growth conditions (Fig. 1). However, both MoSPC5 and MoSPC6 were down-regulated during plant infection, and MoSPC4 was not differentially expressed under the same conditions (data not shown). Based on this expression analysis, we selected MoSPC1, MoSPC2, MoSPC3 and MoSPC7 for targeted deletion and further functional studies.

Fig. 1.

Transcript abundance of MoSPC genes in different development stages of Magnaporthe oryzae. Con, conidia; Ger, germinating conidia; App, appressoria; In 78, infection stage at 78 h post-inoculation (hpi); In 150, infection stage at 150 hpi.

Targeted deletion of selected genes and phenotypes analysis

To investigate the possible roles of the four selected genes in M. oryzae, we generated deletion mutants of individual genes. Gene deletion constructs were prepared through double joint PCR (Yu et al., 2004), in which the HPH cassette was combined with ~1-kb 5′/3′ flanking regions of the target gene (Fig. S1). The gene deletion constructs were used directly for transformation with wild-type protoplasts. The resulting hygromycin-resistant transformants were screened by PCR and correct gene replacement, and the resulting transformants were confirmed using Southern hybridization analysis (Fig. S1).

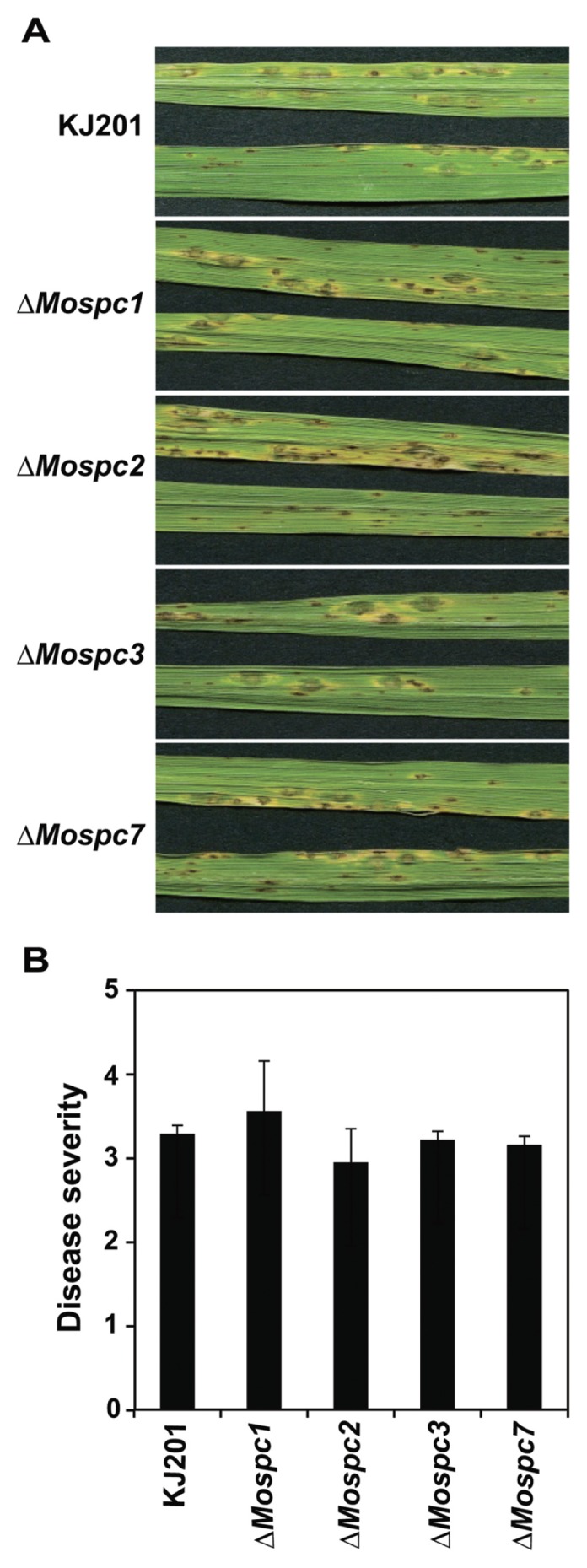

When examining the phenotypes of the deletion mutant in each of the four genes, we found that deletion mutants of MoSPCs were comparable to the wild-type with respect to mycelial growth and conidiation (Table 2). Conidia of all mutants were capable of germinating and developing appressorium on a germ tube tip. The morphology of appressoria formed by the four mutants was indistinguishable from the wild-type. Furthermore, when conidial suspensions of the mutants were spray-inoculated onto rice plants of a susceptible cultivar, Nakdongbyeo, all mutants showed virulence similar to the wild-type strain (Fig. 2A and 2B). These results suggested that MoSPCs are not required for the traits examined, including mycelial growth, conidiation, conidial germination, appressorium formation, and pathogenicity.

Table 2.

Phenotypes of wild-type, ΔMospc1, ΔMospc2, ΔMospc3 and ΔMospc7

| Strain | Mycelial growth (mm)a | Conidiation (× 104/ml) b | Conidial germination (%)c | Appressorium formation (%)d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| MCA | MMA | ||||

| KJ201 | 83.6 ± 0.6 | 78.6 ± 0.6 | 27.8 ± 4.6 | 90.2 ± 1.1 | 84.3 ± 5.4 |

| ΔMospc1 | 83.2 ± 0.7 | 78.0 ± 0.6 | 24.3 ± 9.6 | 90.2 ± 1.1 | 79.4 ± 3.9 |

| ΔMospc2 | 82.2 ± 0.3 | 77.3 ± .03 | 28.3 ± 3.3 | 88.9 ± 0.9 | 79.4 ± 3.9 |

| ΔMospc3 | 81.6 ± 1.6 | 77.0 ± 1.3 | 29.2 ± 4.2 | 90.3 ± 1.3 | 82.3 ± 3.3 |

| ΔMospc7 | 82.3 ± 0.6 | 76.0 ± 1.5 | 26.6 ± 0.6 | 87.1 ± 3.3 | 81.2 ± 3.5 |

Mycelial growth was measured at 12 days after inoculation (DAI) on modified complete agar medium (MCA) and minimal agar medium (MMA).

Conidiation was measured as the number of conidia from a culture flooded with 5 ml of sterilized distilled water.

Percentage of conidial germination was measured on plastic coverslips under a light microscope using conidia harvested from 7-day-old V8 juice agar plates.

Percentage of appressorium formation was measured on plastic coverslips using conidia harvested from 7-day-old V8 juice agar plates.

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Fig. 2.

Pathogenicity assay of wild-type, ΔMospc1, ΔMospc2, ΔMospc3 and ΔMospc7. (A) Disease development after spraying conidial suspension onto rice leaves. Conidial suspension (1×105/ml) was sprayed onto the leaves and diseased leaves were harvested 7 days after inoculation. (B) Disease score measurement was performed on 7-day diseased leaves of all strains, as described by Valent et al., 1991. The data are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments and all data are statistically analyzed using Tukey test (p<0.05).

Genome-wide analysis of orphan genes in M. oryzae

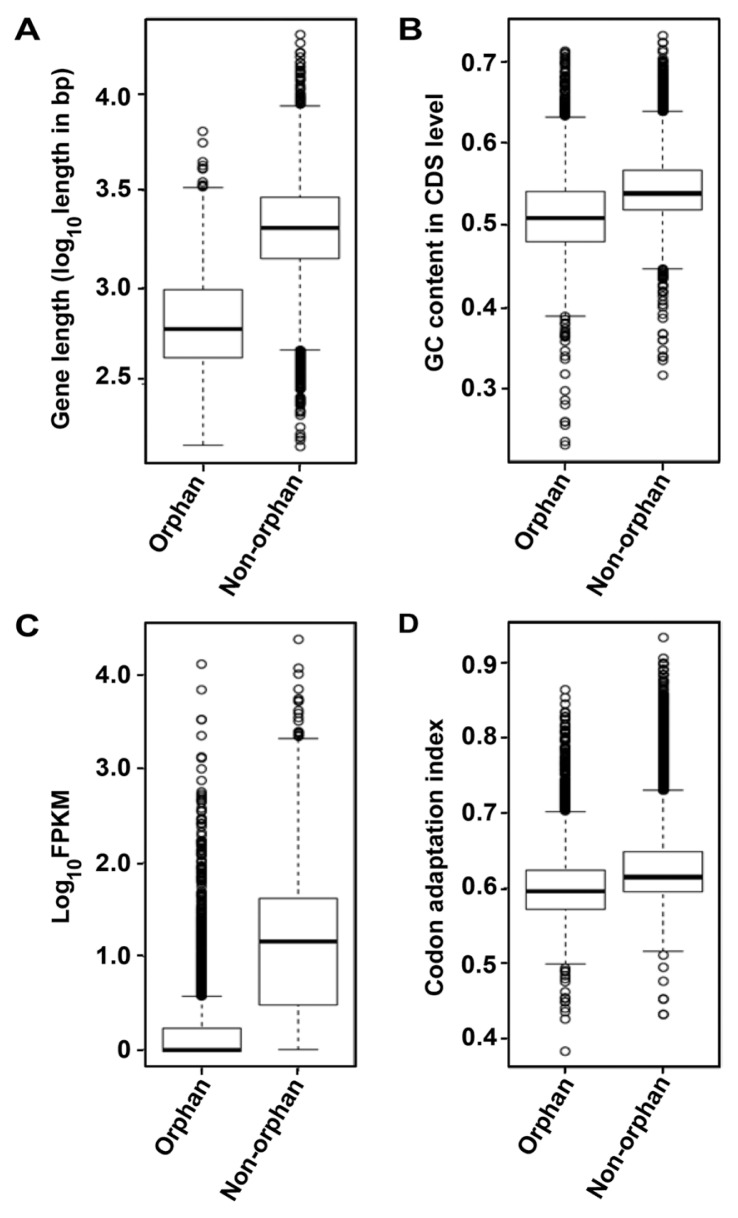

In parallel to the targeted deletion of the four selected genes, we analyzed orphan genes at the genome scale by comparing the features of orphan and non-orphan genes, including gene length, GC contents, transcription and codon adaptation index. Our analysis showed that orphan genes including MoSPCs (excluding MoSPC6) were relatively short (Fig. 3A), showed a low GC content (Fig. 3B), low transcription (Fig. 3C) and less-biased codon usage (Fig. 3D) than their non-orphan counterparts. Gene length is positively associated with both GC content and gene expression (Jansen and Gerstein, 2000; Pozzoli et al., 2008). We also observed such a positive correlation among gene features. The differences between orphan and non-orphans in our analysis are in concordance with the results of previous studies on de novo emergence of orphan genes from model organisms (Cai et al., 2008; Carvunis et al., 2012; Li et al., 2010b; Neme and Tautz, 2013).

Fig. 3.

Genomic features of new born genes in M. oryzae. (A) Gene length, (B) GC content in coding DNA sequence (CDS) level, (C) expression pattern and (D) codon adaptation between new and old genes using the Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test (p<2.2e-16).

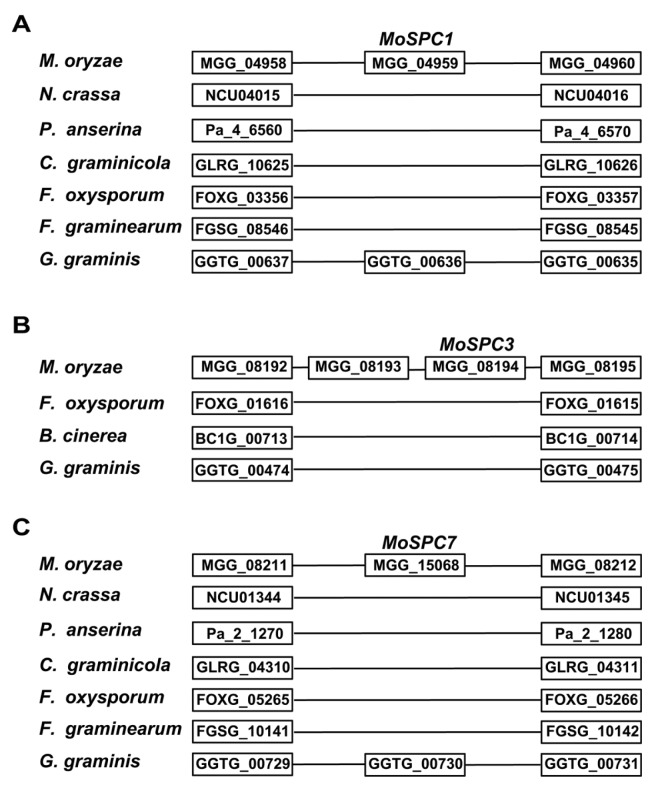

Synteny analysis of orphan genes

The most stringent criterion for involvement of de novo processes in explaining orphan genes requires that syntenic blocks spanning an orphan gene are present in outgroup organisms as non-coding sequences that are not transcribed (Cai et al., 2008; Knowles and McLysaght, 2009). To further support de novo gene birth of the four selected genes, we performed synteny analysis with phylogenetically closely related fungal species, including Gaeumannomyces graminis (a member of the Magnaporthaceae family) (Table S2). Our synteny analysis demonstrated that the selected genes (excluding MoSPC2) were present in the well-conserved synteny block (Fig. 4). We did not detect a synteny block containing MoSPC2, even by expanding the number of fungal species included in the analysis. Based on our analysis, MoSPC3 was the orphan gene that best fit our stringent criterion. In synteny blocks harboring MoSPC1 and MoSPC7, predicted ORFs (GGTG_00636 and GGTG_00730) of G. graminis were found in a region corresponding to the location of MoSPC1 and MoSPC7. However, these two ORFs did not have any similarity to MoSPC1 or MoSPC7 (data not shown). BLASTP searches against the NCBI nr database showed that GGTG_00636 and GGTG_00730 were also likely orphan genes in the G. graminis genome. Based on our observations, at least one of the selected orphan genes (MoSPC3) originated de novo during the evolutionary history of M. oryzae.

Fig. 4.

Synteny relationships of MoSPC genes with other fungal species. Protein sequences from the upstream and downstream flanking regions of MoSPC genes were used for BLASTP searches with a cutoff e-value of 10−5 to identify homologous genes in other organisms. Gene birth of M. oryzae is shown in the upper region.

Discussion

De novo gene birth is an important mechanism in species-specific adaptation processes (Cai et al., 2008; Kaessmann, 2010). Examples of newborn genes have shown that they quickly become essential and play pivotal roles during development, reproduction and survival (Ding et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010a). However, there have been no fully documented cases in plant pathogenic fungi regarding de novo-originated genes, although it is possible that such novel genes contribute to fungal pathogenesis, host specificity and host jumping.

To identify orphan genes in M. oryzae, we performed BLASTP searches against the NCBI nr database. To characterize orphan genes, it is important to understand whether a gene is absent in other species or whether the observed absence is the result of technical limitations of the methods used. This concern was addressed by a recent study showing that BLAST is sufficiently sensitive to detect the majority of remote homologues (Alba and Castresana, 2007). Furthermore, the NCBI nr database includes a variety of sequences, including those from metagenomic studies (Pruitt et al., 2007). A gene is considered to be absent in the genomes of other species if there is no match to the corresponding gene product in a BLASTP search against the NCBI nr database. Using this approach, we identified ~2,700 orphan genes that account for ~21% of genes annotated in the genome. Considering that orphan genes account for approximately 10–20% of total genes in other organisms (Khalturin et al., 2009), the observed proportion of orphans in the genome of M. oryzae was reasonable. Our analysis of orphan versus non-orphan genes showed that orphan genes of M. oryzae possess typical characteristics of genes formed via de novo evolution; namely, short length, low GC contents, low transcriptional activity, and less bias in codon usage.

In this report, we targeted four orphan genes of M. oryzae among ~2,700 orphan genes prioritized by in planta EST data and qRT-PCR to explore the involvement of orphan genes in fungal pathogenesis. Synteny analysis of these four genes indicated that at least one of these genes (MoSPC3) has a de novo origin. Our data suggest that the other three genes may have originated de novo. It is highly likely that homologous genes of MoSPC2 flanking genes are spread in other organisms during evolution, in contrast to M. oryzae in which these genes remain linked. Predicted ORFs of G. graminis (GGTG_00636 and GGTG_00730) are present in the corresponding location of MoSPC1 and MoSPC7 without sequence similarities, which is suggestive of two possibilities. First, the two genes are orthologous between M. oryzae and G. graminis but underwent rapid divergence after the speciation event. Second, each gene emerged de novo from non-coding sequences independently in both species. We argue that the second possibility is more parsimonious than the first considering the small amount of time since speciation events and that the divergence is significant enough to be undetectable using a BLAST search.

Deletion of individual genes (MoSPC1, MoSPC2, MoSPC3 and MoSPC7) did not result in phenotypic changes for traits we examined in this study. This suggests that these four genes are not required for fungal development and pathogenesis. It is also possible that assays we performed to examine phenotypes were not sufficiently sensitive to detect subtle differences that exist between the mutants and wild-type. The absence of phenotypes in deletion mutants of an orphan gene was reported previously in M. grisea. The authors investigated a gene called MIR1, which is unique to M. grisea (Li et al., 2007). Deletion of MIR1 did not cause changes in phenotypes examined. Based on its upregulation during plant infection, MIR1 may be important for the fitness and virulence of M. grisea under field conditions, although it is dispensable for plant infection under laboratory conditions. This may also be true for the four orphan genes investigated in this study.

Alternatively, the absence of phenotypes could be related to evolutionary processes through which orphan genes are gained and retained in the genome. The de novo evolution model of orphan genes suggests a balance between gene emergence and gene loss over time (Palmieri et al., 2014). These genes can be retained if they confer selective advantages, otherwise they are quickly lost. Thus, we may have observed orphan genes that are being selected for retention or extinction through natural selection. In addition, orphan genes present in the majority of field isolates are more likely to have an impact on the fungal life cycle.

In summary, we investigated the role of orphan genes during pathogenesis of M. oryzae through gene deletions. Our data demonstrated that none of these genes are important for fungal development and pathogenicity, despite their upregulation during plant infection processes. We confirmed that at least one of the genes has a de novo origin based on our analyses, including synteny comparison. These results suggest that a significant proportion of the fungal genome is comprised of orphan genes. These genes should be examined to determine their origin and increase our understanding of fungal pathogenesis and evolution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea grants funded by the Korean government (2008-0061897 and 2013-003196), and by the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program of the Rural Development Administration in Korea (PJ00821201). Sadat is grateful for a graduate fellowship through the Brain Korea 21 Program.

References

- Alba MM, Castresana J. On homology searches by protein Blast and the characterization of the age of genes. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun DJ, Lindfors HA, Kern AD, Jones CD. Evidence for de novo evolution of testis-expressed genes in the Drosophila yakuba/Drosophila erecta clade. Genetics. 2007;176:1131–1137. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Zhao RP, Jiang HF, Wang W. De novo origination of a new protein-coding gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2008;179:487–496. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvunis AR, Rolland T, Wapinski I, Calderwood MA, Yildirim MA, Simonis N, Charloteaux B, Hidalgo CA, Barbette J, Santhanam B, Brar GA, Weissman JS, Regev A, Thierry-Mieg N, Cusick ME, Vidal M. Proto-genes and de novo gene birth. Nature. 2012;487:370–374. doi: 10.1038/nature11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi MH, Park SY, Lee YH. A quick and safe method for fungal DNA extraction. Plant Pathol J. 2009;25:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Cheong K, Jung K, Jeon J, Lee GW, Kang S, Kim S, Lee YW, Lee YH. CFGP 2.0: a versatile web-based platform for supporting comparative and evolutionary genomics of fungi and Oomycetes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D714–D719. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant GC, Wolfe KH. Turning a hobby into a job: How duplicated genes find new functions. Nature Rev Genet. 2008;9:938–950. doi: 10.1038/nrg2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RA, Talbot NJ, Ebbole DJ, Farman ML, Mitchell TK, Orbach MJ, Thon M, Kulkarni R, Xu JR, Pan HQ, Read ND, Lee YH, Carbone I, Brown D, Oh YY, Donofrio N, Jeong JS, Soanes DM, Djonovic S, Kolomiets E, Rehmeyer C, Li WX, Harding M, Kim S, Lebrun MH, Bohnert H, Coughlan S, Butler J, Calvo S, Ma LJ, Nicol R, Purcell S, Nusbaum C, Galagan JE, Birren BW. The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature. 2005;434:980–986. doi: 10.1038/nature03449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Zhao L, Yang SA, Jiang Y, Chen YA, Zhao RP, Zhang Y, Zhang GJ, Dong Y, Yu HJ, Zhou Q, Wang W. A Young Drosophila duplicate gene plays essential roles in spermatogenesis by regulating several Y-linked male fertility genes. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domazet-Loso T, Tautz D. An evolutionary analysis of orphan genes in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2003;13:2213–2219. doi: 10.1101/gr.1311003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue MTA, Keshavaiah C, Swamidatta SH, Spillane C. Evolutionary origins of Brassicaceae specific genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011;11:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman D, Elofsson A. Identifying and quantifying orphan protein sequences in fungi. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;396:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SA. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) Science. 2005;309:879–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen TJAJ, Staubach F, Haming D, Tautz D. Emergence of a new gene from an intergenic region. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1527–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R, Gerstein M. Analysis of the yeast transcriptome with structural and functional categories: characterizing highly expressed proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1481–1488. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaessmann H. Origins, evolution, and phenotypic impact of new genes. Genome Res. 2010;20:1313–1326. doi: 10.1101/gr.101386.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalturin K, Hemmrich G, Fraune S, Augustin R, Bosch TCG. More than just orphans: are taxonomically-restricted genes important in evolution? Trends Genet. 2009;25:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Han JH, Kim KS, Lee YH. Comparative functional analysis of the velvet gene family reveals unique roles in fungal development and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014;66:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Park J, Park SY, Mitchell TK, Lee YH. Identification and analysis of in planta expressed genes of Magnaporthe oryzae. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles DG, McLysaght A. Recent de novo origin of human protein-coding genes. Genome Res. 2009;19:1752–1759. doi: 10.1101/gr.095026.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MT, Jones CD, Kern AD, Lindfors HA, Begun DJ. Novel genes derived from noncoding DNA in Drosophila melanogaster are frequently X-linked and exhibit testis-biased expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2006;103:9935–9939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509809103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CY, Zhang Y, Wang ZB, Zhang Y, Cao CM, Zhang PW, Lu SJ, Li XM, Yu Q, Zheng XF, Du Q, Uhl GR, Liu QR, Wei LP. A human-specific de novo protein-coding gene gssociated with human brain functions. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010a;6:e1000734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Dong Y, Jiang Y, Jiang HF, Cai J, Wang W. A de novo originated gene depresses budding yeast mating pathway and is repressed by the protein encoded by its antisense strand. Cell Res. 2010b;20:408–420. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Ding SL, Sharon A, Orbach M, Xu JR. Mir1 is highly upregulated and localized to nuclei during infectious hyphal growth in the rice blast fungus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20:448–458. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-4-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Katju V. The altered evolutionary trajectories of gene duplicates. Trends Genet. 2004;20:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Moran GP, Jacobsen ID, Heyken A, Domey J, Sullivan DJ, Kurzai O, Hube B. The Candida albicans-specific gene EED1 encodes a key regulator of hyphal extension. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neme R, Tautz D. Phylogenetic patterns of emergence of new genes support a model of frequent de novo evolution. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri N, Kosiol C, Schlotterer C. The life cycle of Drosophila orphan genes. eLife. 2014;3:e01311. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Chi MH, Milgroom MG, Kim H, Han SS, Kang S, Lee YH. Genetic stability of Magnaporthe oryzae during successive passages through rice plants and on artificial medium. Plant Pathol. J. 2010;26:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzoli U, Menozzi G, Fumagalli M, Cereda M, Comi GP, Cagliani R, Bresolin N, Sironi M. Both selective and neutral processes drive GC content evolution in the human genome. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Siepel A. Darwinian alchemy: Human genes from noncoding DNA. Genome Res. 2009;19:1693–1695. doi: 10.1101/gr.098376.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot NJ. On the trail of a cereal killer: Exploring the biology of Magnaporthe grisea. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:177–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot NJ, Ebbole DJ, Hamer JE. Identification and characterization of Mpg1, a gene involved in pathogenicity from the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1575–1590. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.11.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Domazet-Loso T. The evolutionary origin of orphan genes. Nature Rev Genet. 2011;12:692–702. doi: 10.1038/nrg3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent B, Chumley FG. Molecular genetic analysis of the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe grisea. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1991;29:443–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.29.090191.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent B, Farrall L, Chumley FG. Magnaporthe grisea genes for pathogenicity and virulence identified through a series of backcrosses. Genetics. 1991;127:87–101. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RA, Talbot NJ. Under pressure: investigating the biology of plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:185–195. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZF, Huang JL. De novo origin of new genes with introns in Plasmodium vivax. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:641–644. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Hu SN, Wang J, Wong GKS, Li SG, Liu B, Deng YJ, Dai L, Zhou Y, Zhang XQ, Cao ML, Liu J, Sun JD, Tang JB, Chen YJ, Huang XB, Lin W, Ye C, Tong W, Cong LJ, Geng JN, Han YJ, Li L, Li W, Hu GQ, Huang XG, Li WJ, Li J, Liu ZW, Li L, Liu JP, Qi QH, Liu JS, Li L, Li T, Wang XG, Lu H, Wu TT, Zhu M, Ni PX, Han H, Dong W, Ren XY, Feng XL, Cui P, Li XR, Wang H, Xu X, Zhai WX, Xu Z, Zhang JS, He SJ, Zhang JG, Xu JC, Zhang KL, Zheng XW, Dong JH, Zeng WY, Tao L, Ye J, Tan J, Ren XD, Chen XW, He J, Liu DF, Tian W, Tian CG, Xia HG, Bao QY, Li G, Gao H, Cao T, Wang J, Zhao WM, Li P, Chen W, Wang XD, Zhang Y, Hu JF, Wang J, Liu S, Yang J, Zhang GY, Xiong YQ, Li ZJ, Mao L, Zhou CS, Zhu Z, Chen RS, Hao BL, Zheng WM, Chen SY, Guo W, Li GJ, Liu SQ, Tao M, Wang J, Zhu LH, Yuan LP, Yang HM. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica) Science. 2002;296:79–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1068037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JH, Hamari Z, Han KH, Seo JA, Reyes-Dominguez Y, Scazzocchio C. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41:973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Zhang GJ, Zhang Y, Xu SY, Zhao RP, Zhan ZB, Li X, Ding Y, Yang SA, Wang W. On the origin of new genes in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2008;18:1446–1455. doi: 10.1101/gr.076588.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]