Abstract

This study sought to control the root-knot nematode (RKN) Meloidogyne incognita using benign organo-chemicals. Second-stage juveniles (J2) of RKN were exposed to dilutions (1.0%, 0.5%, 0.2%, and 0.1%) of acetic acid (AA), lactic acid (LA), and their mixtures (MX). The nematode bodies were disrupted severely and moderately by vacuolations in 0.5% of MX and single organic acids, respectively, suggesting toxicity of MX may be higher than AA and LA. The mortality of J2 was 100% at all concentrations of AA and MX and only at 1.0% and 0.5% of LA, which lowered slightly at 0.2% and greatly at 0.1% of LA. This suggests the nematicidal activity of MX may be mostly derived from AA together with supplementary LA toxicity. MX was applied to chili pepper plants inoculated with about 1,000 J2, for which root-knot gall formations and plant growths were examined 4 weeks after inoculation. The root gall formation was completely inhibited by 0.5% MX and standard and double concentrations of fosthiazate; and inhibited 92.9% and 57.1% by 0.2% and 0.1% MX, respectively. Shoot height, shoot weight, and root weight were not significantly (P ≤ 0.05) different among all treatments and the untreated and non-inoculated controls. All of these results suggest that the mixture of the organic acids may have a potential to be developed as an eco-friendly nematode control agent that needs to be supported by the more nematode control experiments in fields.

Keywords: control, Meloidogyne incognita, nematode mortality, organic acids, root gall formation

Root-knot nematodes (RKNs), Meloidogyne spp., are distributed globally and attack more than 2,000 plant species (Sasser and Carter, 1985). They cause crop yield losses of about 5% and devastate some crops, mainly through the formation of root-knot galls (Flanklin, 1982; Oka et al., 2000; Sasser, 1977). Four RKN species, Meloidogyne incognita, M. arenaria, M. hapla, and M. javanica are the major RKNs found globally (Flanklin, 1982). In South Korea, M. incognita is commonly distributed in warmer environments, such as greenhouse soils (Kim, 2001; Kim et al., 2001).

Use of chemicals, such as soil fumigant and non-fumigant nematicides, is a common practice for the control of plant-parasitic nematodes, including RKNs (Kim, 2001; Whitehead and Winfield, 1982). This is particularly true for nematode control for high value crops that are grown in controlled environmental conditions such as greenhouses. The high crop value compensates the high cost of nematicide application. However, nematicides are very toxic to humans and animals, causing pesticide residues in food and both soil and water pollution (Aktar et al., 2009). Hence, developing safe and ecofriendly nematode control alternatives that are readily available to farmers is urgent.

Organic amendments have been used as alternatives to nematicide chemicals, which can limit the severity of plant-parasitic nematode damage (Akhtar and Alam, 1992, 1993; Akhtar and Mahmood, 1994; McBride et al., 2000). Organic acids released during the decomposition of organic materials are one of many factors contributing to reductions in nematode damage (Badra et al., 1979; Johnston, 1959; McBride et al., 2000; Stephenson, 1945; Sayre et al., 1964), but little is known about the direct effects of low-molecular-weight organic acids for nematode control. In our study, we examined the potential of low-molecular-weight organic acids in the control of the RKN M. incognita using acetic and lactic acids (AA and LA, respectively) that are edible and found in condiments (e.g., vinegar) and sour milk products, respectively.

A population of M. incognita race 1 cultured on Capsicum annuum cv. Bugang was used as nematode inoculum (Seo et al., 2014). Egg masses of RKNs were obtained from culture grown on plants for about 6 weeks and incubated on Baermann funnels for 4 days to obtain nematode second-stage juveniles (J2) (Southey, 1986). They were diluted in sterile distilled water (SDW) to inoculum concentrations of J2 required for in vitro and pot experiments.

In our study, two edible organic acids, AA and LA, were used in in vitro screening for nematicidal activity against M. incognita. Glacial AA and pure LA (Duksan Chemical Company, Seoul, Korea) were diluted with SDW to the concentrations of 1.0%, 0.5%, 0.2%, and 0.1%. Dilutions were also made by mixing the same concentrations of AA and LA in organic acid mixtures (MX) containing half concentrations of each organic acid. The organic acid solutions were transferred to wells of a 96-well Microtest™ Tissue Culture Plate (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with three replications, into which about 80 M. incognita J2 were placed. SDW was used as a control. After 24 h of exposure, M. incognita J2 were examined under a low-power stereoscopic microscope, and determined dead or alive depending on their shape (straight and stiffened, or flexible) and mobility responding to probes with a fine needle (Cayrol et al., 1989). After this experiment, J2 in the treatment and control were examined under a compound light microscope (Axiophot; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) to visualize the detailed structural differences between the dead and live J2.

The MX treatments were tested on the host plant chili pepper (C. annuum cv. Bugang) for control of M. incognita (Moon et al., 2010). Four-week-old chili pepper seedlings planted in 8-cm-diameter plastic pots filled with 1 : 1 mixture of sterilized sand and potting soil (Baroker, Seoul Bio, Korea) were inoculated with 10 mL of the nematode solution containing about 1,000 M. incognita J2 by distributing the nematode solution around the rhizosphere of the plants. For nematode control, 10 mL of MX dilutions was poured around the plant rhizosphere 4 h after inoculation. A liquid formulation (30%) of an organophosphate nematicide (fosthiazate 30% SL), was also applied to the plants with the same amount (10 ml) of its standard (250 μl/l) and double (500 μl/l) concentrations to examine its effect on nematode control. Plants without nematode inoculation and MX treatment served as non-inoculated and untreated controls, respectively. Each treatment was replicated five times, and the pot experiments were conducted at 25 ± 2ºC under greenhouse conditions. Plants were watered on alternating days. Four weeks after treatments, plants were carefully uprooted, and root-knot galling was examined after the root systems were washed with running tap water to remove soil. The severity of root galling (gall index, GI) was assessed on a 0–5 rating scale, according to the percentage of galled tissues, for which GI was 0 = 0–10%, 1 = 11–20%, 2 = 21–50%, 3 = 51–80%, 4 = 81–90%, and 5 = 91–100% galled roots (Barker, 1985). Concurrently, shoot height, fresh shoot weight, and fresh root weight were recorded to study the positive or detrimental effects of MX treatments and the nematicide on plant growths.

After the exposure of M. incognita J2 to organic acids for 24 h, they were examined under a stereomicroscope for shape and mobility. Nematodes on the plants with no organic acids treatment were alive. They were characterized as flexible and mobile. Nematodes were straight, stiffened, and immobile for all the organic acid treatments, except for 0.1% of LA (not photographed). Examination of the flexible nematode bodies showed a definite anterior profile of the armature (stylet) and esophageal structure, and intact middle and posterior regions of the nematode body. The stiffened nematode bodies had an indistinct contour of anterior structures and were full of vacuoles in the median and posterior regions, indicating vacuolations of the nematode body (Fig. 1). Severe vacuolations occurred in MX that might disrupt nematode body cavity by forming a great number of vacuoles, while vacuolations were relatively moderate in single AA and LA by small number of vacuoles formed in the body cavity (Fig. 1). This suggests the nematicidal activity of MX may be higher than that of the single organic acids at the same concentrations. Prominent vacuoles are formed in heat-shocked juveniles and embryos of Caenorhabditis elegans as an indication of cell disruption, which appear as craterlike, swollen, membrane-bound units structurally identical to the vacuoles formed in our study (Harbinder et al., 1997). This suggests that organic acids may induce rapid cell and tissue disruption of the nematode body, resembling heat shock and implying acute rather than chronic nematostatic toxicity.

Fig. 1.

Light micrographs of anterior (A–D), median (E–H), and posterior (I–L) regions of Meloidogyne incognita J2 treated with none (A, E, I), acetic acid (B, F, J), lactic acid (C, G, K), and their mixture (D, H, L) for 24 h, showing extensive vacuolation (arrows) of the immobile stiffened nematodes, which were not found in mobile flexible nematodes. Bars = 10 μm.

Complete mortality of J2 was observed in all concentrations of AA and MX and in 1.0% and 0.5% of LA, but not in 0.2% (93.5% mortality) and 0.1% (5.3% mortality) of LA (Table 1). At the concentration of 0.1%, nematode mortalities induced by MX (mixture of 0.05% AA and 0.05% LA) were significantly higher than those by LA and equivalent to those by AA. These results suggest that the nematicidal activity of AA should be higher than that of LA, and that the nematicidal activity of MX may be mostly derived from AA together with a supplementary toxicity from LA. Considering the aspects that AA concentration in MX was a half of the sole AA and occurrence of more extensive body cavity disruption in MX than AA at the same concentrations (Fig. 1), there may be somewhat enhanced nematicidal activity of MX compared to the single AA.

Table 1.

Effect of organic acids [acetic acid (AA), lactic acid (LA) and their mixture (MX)] on the mortality of Meloidogyne incognita

| Treatment (conc., m/v) | Nematode mortality (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| AA | LA | MXb | |

| 1.0% | 100.0 ± 0.0acxd | 100.0 ± 0.0ax | 100.0 ± 0.0ax |

| 0.5% | 100.0 ± 0.0ax | 100.0 ± 0.0ax | 100.0 ± 0.0ax |

| 0.2% | 100.0 ± 0.0ax | 93.5 ± 3.3bx | 100.0 ± 0.0ax |

| 0.1% | 100.0 ± 0.0ax | 5.3 ± 1.3cy | 100.0 ± 0.0ax |

| 0.0% | 1.6 ± 1.4bx | 1.6 ± 1.4cx | 1.6 ± 1.4bx |

Data are averages and standard deviations of three replications.

About 80 second-stage juveniles of M. incognita were immersed in the same volume of organic acid dilutions and examined one day after treatment.

Mixture concentration is the sum of concentrations for the same volumes of each organic acid (ex. 0.5% MX = 0.25% AA + 0.25% LA).

Means with the same letters in a column denote no significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 by Duncan’s multiple range test.

Means with the same letters in a row denote no significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 by Duncan’s multiple range test.

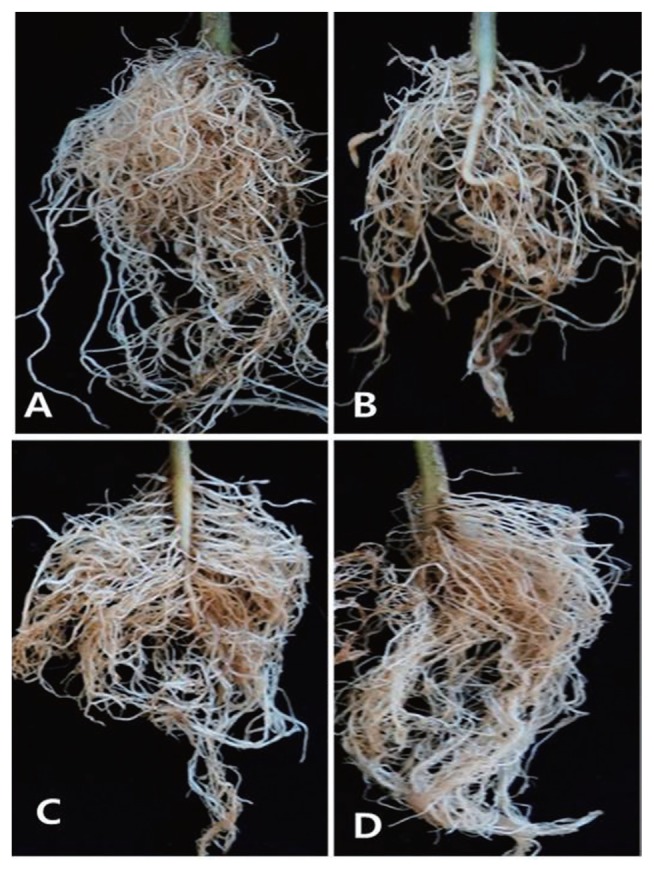

In the pot experiments under greenhouse conditions, root-knot galls were readily formed, with about 50% of the chili pepper roots forming galls 4 weeks after inoculation with M. incognita (Figs. 2, 3). The galls were significantly suppressed by the treatments of the nematicide and MX at all concentrations except for 0.1% MX, which showed no significant difference from the untreated control (Fig. 2). Almost complete inhibition of the gall formation was observed for the treatments of nematicide fosthiazate and 0.5% and 0.2% MX, with no significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) among these treatments. Initial distribution of chemicals and their redistribution by diffusion and leaching in the soil are related to the control efficacy of nematicidal materials applied in fields (Bromilow, 1973). Non-fumigant nematicides such as fosthiazate have relatively low mobility in the soil, particularly in soil containing high organic matter. The soil must be thoroughly mixed to evenly distribute this type of nematicide (Whitehead and Winfield, 1982). In contrast, low-molecular-weight organic acids diffuse more readily because of their higher mobility than non-fumigant nematicides. This suggests that organic acids with lower molecular weight are more easily distributed and incorporated into the soil compared to the higher-molecular-weight nematicides and aliphatic acids such as citric and oxalic acids that readily form stable complexes with metals in the soil (Brynhildsen and Rosswall, 1997; Fox and Comerford, 1990; Stevenson and Ardakani, 1972).

Fig. 2.

Degree of root gall formation on chili pepper plants influenced by several treatments [Con: no inoculation and no treatment, MI: inoculation alone, Fosth-1: inoculation + 1× fosthiazate, Fosth-2: inoculation + 2× fosthiazate, MX(0.5): 0.5% mixture of AA and LA, MX(0.2): 0.2% mixture of AA and LA, and MX(0.1): mixture of AA and LA] 4 weeks after inoculation with M. incognita. Gall index: 0 = 0–10%, 1 = 11–20%, 2 = 21–50%, 3 = 51–80%, 4 = 81–90%, and 5 = 91–100% of roots galled (Bakers, 1985). Bars and vertical lines denote averages and standard deviations of five replications, respectively.

aMean values of gall index with the same letters denote no significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 by Duncan’s multiple range test.

bControl value (%) = (gall index of MI – gall index of treatment)/(gall index of MI) × 100.

Fig. 3.

Gall formation on chili pepper roots with no inoculation and no treatment (A), inoculation only (B), inoculation + organic acid mixture (C), and inoculation + fosthiazate (D). Note that severe gall formation was found only in (B).

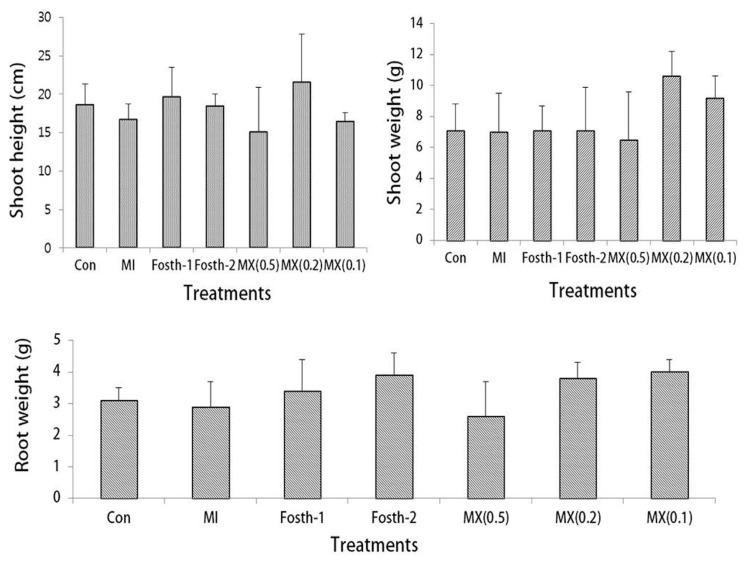

No significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) were observed in shoot height, fresh shoot weight, and fresh root weight among all treatments and the untreated and non-inoculated controls (Fig. 4). Averages of all these growth characteristics were lowest in 0.5% MX treatments; however, all or two (shoot and root weights) of them were somewhat stimulated in 0.2% and 0.1% MX, respectively. This suggests that MX promotes plant growth at lower concentrations (0.1%–0.2%), probably due to the nematode control, but that it has phytotoxicity at higher concentrations (≥ 0.5%). The phytotoxicity problem of MX at higher concentrations in fields may be solved by applying a large amount of MX at lower concentrations. Reducing initial concentrations and increasing distribution and persistence in the soil would have an effect equivalent to the small amount of MX applied at higher concentrations. The concentration–time product (CTP) achieved determines the nematode control efficacy, and at the same CTP, the lower concentration and longer operational time are more effective in the control of plant-parasitic nematodes compared to the higher concentration and shorter operational time (Hague and Sood, 1963; Hague et al., 1964). Thus, this application method of MX may not only reduce phytotoxicity, but also enhance efficacy in controlling RKNs.

Fig. 4.

Plant growths (A: shoot height, B: shoot weight, C: root weight) of chili pepper plants influenced by various treatments [Con: no inoculation and no treatment, MI: inoculation alone, Fosth-1: inoculation + 1× nematicide fosthiazate, Fosth-2: inoculation + 2× fosthiazate, MX(0.5): 0.5% mixture of acetic acid (AA) and lactic acid (LA), MX (0.2): 0.2% mixture of AA and LA, and MX (0.1): 0.1% mixture of AA and LA] 4 weeks after inoculation with M. incognita. Bars and vertical lines are averages and standard deviations of five replications, respectively.

Concentrated AA is corrosive and harmful to health, but when diluted at about 4–8%, it is used as table vinegar. LA is approved for use as a food additive in several countries and found commonly in fermented milk products such as yogurt. These organic acids are used very safely as agricultural materials for nematode control. The prices of these two organic acids (AA: US $0.499–0.699/kg, LA: US $5.0–13.0/kg) are lower than or comparable to agrochemical nematicides (fosthiazate 10% GR: US$7.0–9.0/kg) (http://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/). Considering the amount of organic acids included in our study, the control cost in using MX would be approximately equal to that of the agrochemical nematicide. This may provide an economic advantage of MX over biocontrols with beneficial microorganisms, which have generally failed to provide adequate nematode control (Upadhyay and Rai, 1988). However, more trials of the nematode control in field conditions would be required to confirm the control efficacy of MX, its practical concentration and control cost, compared to those of the nematicide fosthiazate.

A disadvantage of low-molecular-weight organic acids is their rapid disappearance from the soil (Lynch, 1991; McBride et al., 2000; Schwartz et al., 1954). The reduced efficacy resulting from the lower persistence of these chemicals would be overcome when they are used in small places with controlled irrigation and drainage, such as in greenhouses where a variety of valuable crops are cultivated and the RKN M. incognita is commonly distributed. Also, LA in MX with higher molecular weight than AA may help to sustain RKN control because organic acids with higher molecular weights form stable complexes with metals in soil, but not those with lower molecular weights (Fox and Comerford, 1990).

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported in part by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (Project number; 311010-03-3-SB010), Republic of Korea.

References

- Akhtar M, Alam MM. Effect of crop residues amendments to soil for the control of plant-parasitic nematodes. Bioresour Technol. 1992;41:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M, Alam MM. Utilization of waste materials in nematode control: A review. Bioresour Technol. 1993;45:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M, Mahmood I. Potentiality of phytochemicals in nematode control: A review. Bioresour Technol. 1994;48:189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Aktar MW, Sengupta D, Chowdhury A. Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: Their benefits and hazards. Interdisc Toxicol. 2009;2:1–12. doi: 10.2478/v10102-009-0001-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badra T, Mahmound SA, Bakir OA. Nematicidal activity and composition of some organic fertilizers and amendments. Rev Nematol. 1979;2:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Barker KR. Nematode extractions and bioassays. In: Barker KR, Carter CC, Sasser JN, editors. An advanced treatise on Meloidogyne, Vol II Methodology. North Carolina State University; Raleigh, NC, USA: 1985. pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bromillow RH. Breakdown and fate of oximecarbamate nematicides in crops and soils. Ann Appl Biol. 1973;75:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Brynhildsen L, Rosswall T. Effects of metals on the microbial mineralization of organic acids. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1997;94:45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cayrol JC, Djian C, Pijarowski L. Study of the nematicidal properties of the culture filtrate of the nematophagous fungus Paecilomyces lilacinus. Rev Nématol. 1989;12:331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Flanklin MT. Meloidogyne. In: Southey JF, editor. Plant nematology. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office; London, UK: 1982. pp. 98–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fox TR, Comerford NB. Low-molecular-weight organic acids in selected forest soils of the southeastern USA. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1990;54:1139–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Hague NGM, Lubatti OF, Page ABP. Methyl bromide fumigation of nematodes in soil under gas-proof sheet. Hort Res Edinb. 1964;3:84–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hague NGM, Sood U. Soil solarization with methyl bromide to control soil nematodes. Plant Pathol. 1963;12:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Harbinder S, Tavernarakis N, Herndon LA, Kinnell M, Xu SQ. Genetically targeted cell disruption in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13128–13133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston TM. Effect of fatty acid mixtures on the rice styles nematode (Tylenchorhynchus martini Fielding, 1956) Nature. 1959;183:1392. doi: 10.1038/1831392a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DG. Occurrence of root-knot nematodes on fruit vegetables under greenhouse conditions in Korea. Res Plant Dis. 2001;7:69–79. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim DG, Lee YG, Park BY. Root-knot nematode species distributing in greenhouses and their simple identification. Res Plant Dis. 2001;7:49–55. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JM. Sources and fate of soil organic matter. In: Wilson WS, editor. Advances in soil organic matter research : The impact on agriculture and the environment. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, UK: 1991. pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- McBride RG, Mikkelsen RL, Barker KR. The role of low molecular weight organic acids from decomposing rye in inhibiting root-knot nematode populations in soil. Appl Soil Ecol. 2000;15:243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Moon HS, Khan Z, Kim SG, Son SH, Kim YH. Biological and structural mechanisms of disease development and resistance in chili pepper infected with the root-knot nematode. Plant Pathol J. 2010;26:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Koltai H, Bar-Eyal M, Mor M, Sharon E, Chet I, Spiegel Y. New strategies for the control of plant-parasitic nematodes. Pest Manage Sci. 2000;56:983–988. [Google Scholar]

- Sasser JN. Worldwide dissemination and importance of the root-knot nematodes, Meloidogyne spp. J Nematol. 1977;9:26–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasser JN, Carter CC. Overview of the International Meloidogyne Project 1975–1984. In: Sasser JN, Carter CC, editors. An advanced treatise on Meloidogyne, Vol. 1. Biology and control. North Carolina State University Graphics; Raleigh, NC, USA: 1985. pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer RM, Patrick ZA, Thorpe H. Substances toxic to plant-parasitic nematodes in decomposing plant residue. Phytopathol Annu Abstr. 1964;54:905. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SM, Vamer JF, Martin WP. Separation of organic acids from several dormant and incubated Ohio soils. Soil Sci Soc Am Proc. 19541954:174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y, Park J, Kim YS, Park Y, Kim YH. Screening and histopathological characterization of Korean carrot lines for resistance to the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Plant Pathol J. 2014;30:75–81. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.08.2013.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southey JF. Laboratory methods for work with plant and soil nematodes. Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food. HMSO; London, UK: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson W. The effects of acid on a soil nematode. Parasitology. 1945;36:158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson FJ, Ardakani MS. Organic matter reactions involving micronutrients in soils. In: Mortvedt JJ, Giordano PM, Lindsay WL, editors. Micronutrients in agriculture. Soil Science Society of America; Madison, WI: 1972. pp. 79–114. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay RS, Rai B. Biocontrol agents of plant pathogens: their use and practical constraints. In: Mukerji KG, Garg KL, editors. Biocontrol of plant diseases. Vol. 1. CRC Press, Inc; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 1988. pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead AG, Winfield AL. Chemical control. In: Southey JF, editor. Plant nematology. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office; London, UK: 1982. pp. 283–301. [Google Scholar]