Abstract

Our recent work implicated nitric oxide (NO) in the control of sweating during intermittent exercise; however, it is unclear if cyclooxygenase (COX) is also involved. On separate days, ten healthy young (24 ± 4 years) males cycled in the heat (35°C). Two 30 min exercise bouts were performed at either a moderate (400 W, moderate heat load) or high (700 W, high heat load) rate of metabolic heat production and were followed by 20 and 40 min of recovery, respectively. Forearm sweating (ventilated capsule) was evaluated at four skin sites that were continuously perfused via intradermal microdialysis with: (1) lactated Ringer solution (Control), (2) 10 mm ketorolac (a non-selective COX inhibitor), (3) 10 mm NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; a non-selective NO synthase inhibitor) or (4) a combination of 10 mm ketorolac + 10 mml-NAME. During the last 5 min of the first exercise at moderate heat load, forearm sweating (mg min−1 cm−2) was equivalently reduced with ketorolac (0.54 ± 0.08), l-NAME (0.55 ± 0.07) and ketorolac+l-NAME (0.56 ± 0.08) compared to Control (0.67 ± 0.06) (all P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained for the second exercise at moderate heat load (all P < 0.05). However, forearm sweating was similar between the four sites during exercise at high heat load and during recovery regardless of exercise intensity (all P > 0.05). We show that (1) although both COX and NO modulate forearm sweating during intermittent exercise bouts in the heat at a moderate heat load, the effects are not additive, and (2) the contribution of both enzymes to forearm sweating is less evident during intermittent exercise when the heat load is high and during recovery.

Introduction

In humans, heat stress promotes the heat loss responses of sweating and cutaneous active vasodilation to maintain a stable core body temperature. The mechanism(s) underpinning sweating and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress have been widely examined (Kellogg et al. 1998; Shibasaki & Crandall, 2001; McCord et al. 2006; Welch et al. 2009; Buono et al. 2011; Machado-Moreira et al. 2012; Metzler-Wilson et al. 2014), which has led to a number of identified modulators. For example, cutaneous active vasodilation associated with increases in core body temperature is attenuated when nitric oxide (NO) production is blunted via non-selective NO synthase (NOS) inhibition relative to a control skin site during passive heating at rest (Kellogg et al. 1998; Stanhewicz et al. 2013; Swift et al. 2013; Wong, 2013) and during exercise (Welch et al. 2009; McGinn et al. 2014). The cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme is also known to be involved in vascular regulation. The COX pathways are more complex, as the activation of COX can increase not only thromboxanes, which bind to thromboxane receptors causing vasoconstriction, but also prostacyclins, which activate prostacyclin receptors resulting in vasodilation. McCord et al. (2006) reported that a skin site receiving a non-selective COX inhibitor exhibited reduced cutaneous vasodilation in comparison to a control skin site during passive heating at rest. Their findings reveal that COX enzyme produces vasodilator prostanoids such as prostacyclin, contributing to cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress.

Although a role for NO in modulating sweating in humans was not observed in earlier studies employing passive heat stress (Kellogg et al. 1998; Shastry et al. 1998), subsequent studies revealed that NO is indeed involved in sweating in young adults during continuous exercise at 60% of maximal oxygen consumption (Welch et al. 2009) and during intermittent exercise at 300 W m−2 of metabolic heat load (equivalent to ∼52% of maximal oxygen consumption) (Stapleton et al. 2014). By contrast, the presence of COX has been observed in the human eccrine sweat gland (Muller-Decker et al. 1999), and local administration of prostaglandins E1 and E2, which are metabolites derived from COX, causes increased sweat secretion from the eccrine sweat glands in vitro (Sato, 1993). However, a role for local COX in modulating eccrine sweating in vivo has yet to be examined. The evaporation of sweat is the major avenue for heat loss when ambient temperature equals or exceeds skin temperature (e.g. ∼35°C) (Gisolfi & Wenger, 1984). COX inhibitors such as aspirin are frequently prescribed as an analgesic, antipyretic or to minimize the risk for cardiovascular diseases (Nemerovski et al. 2012). Therefore, for a better understanding of how COX inhibitors may potentially impair core body temperature regulation and thus increase the risk of heat-related illness, it is imperative to elucidate how COX may modulate the sweating response during exercise. Moreover, it was postulated that there exists an interaction between COX and NOS enzyme pathways (Salvemini et al. 1993; Chen et al. 1997). Accordingly, COX-dependent mechanisms may be involved in NO-mediated sweating as observed in exercising humans (Stapleton et al. 2014).

All human studies examining the mechanisms of sweating during exercise, as introduced above, present conclusions based solely on information derived from one arbitrary exercise intensity and therefore metabolic heat load. However, the mechanisms regulating sweating during exercise may be different depending on exercise intensity. For example, higher intensity exercise causes greater oxidative stress (e.g. increased amounts of superoxide) (Wang et al. 2006). It is well recognized that superoxide binds easily to NO, thereby reducing its bioavailability and forming peroxynitrite. Additionally, peroxynitrite inhibits the biosynthesis of prostacyclin, a product of COX (Zou & Ullrich, 1996). Hence NO- and COX-dependent sweating may be diminished when exercising at higher intensities, and therefore greater metabolic heat loads. There is also a lack of information on the underlying pathways governing the control of sweating following exercise and during a subsequent exercise bout. Studies show that there is a more rapid increase in sweating during subsequent exercise compared to the first bout, and this has been termed the priming effect (Gagnon & Kenny, 2011). However, this is not paralleled by a more pronounced rate of heat dissipation in recovery. Rather, there is a rapid suppression of heat loss responses that remains intact despite a progressive increase in heat storage with successive exercise bouts. Taken together, these observations suggest that the underlying mechanisms involved in the activation and/or regulation of heat loss may differ with successive exercise/recovery cycles. Notably, we recently found that NO-dependent sweating remained intact with repeated exercise bouts in young adults whereas the influence of NO on sweating during recovery was less evident (Stapleton et al. 2014). As with NO, any contribution of COX to sweating during exercise may remain intact with subsequent exercise; however, the contribution may be minimal during recovery.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the separate and combined influence of NO and COX on sweating during intermittent exercise (i.e. two 30 min exercise bouts followed by a 20 and 40 min recovery period, respectively) performed on separate days at either a moderate (400 W) or high (700 W) fixed rate of metabolic heat production in the heat (35°C). We hypothesized that (1) both NO and COX contribute to sweating during the first and second exercise bouts at moderate heat loads, but the combined influence of NO and COX would not be additive; and (2) the influence of NO and COX on sweating would be less evident during the first and second exercise bouts at the high heat load as well as during all recovery periods.

Methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Ottawa Health Sciences and Science Research Ethics Board and conformed to the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers prior to their participation in the study.

Subjects

Ten healthy, habitually active (2–4 days per week, ≥30 min of exercise per day), young males participated in this study. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, autonomic disorders or cigarette smoking. All subjects were not currently taking prescription medications. The subjects’ body mass, height and surface area as well as age, maximal oxygen consumption and percentage of body fat were (mean ± SD) 80.7 ± 13.7 kg, 1.74 ± 0.09 m, 1.95 ± 0.18 m2, 24 ± 4 years, 45.0 ± 5.7 ml kg−1 min−1 and 15.4 ± 9.0%, respectively, as determined during a preliminary session (see below).

Experimental procedures

This study consisted of one preliminary and two experimental sessions. All subjects abstained from taking prescribed medications (including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and vitamins) for at least 24 h before each session as well as alcohol, caffeine and heavy exercise at least 12 h before each session. On the study day, they did not take any food 2 h before and throughout the experimental sessions. During the preliminary session body height, mass, surface area and density as well as maximal oxygen consumption were determined. Body height was measured using an eye-level physician stadiometer (Model 2391, Detecto Scale Company, Webb City, MO, USA), while body mass was measured using a digital weight scale platform (Model CBU150X, Mettler Toledo Inc., Schwerzenbach, Switzerland) with a weighing terminal (Model IND560, Mettler Toledo Inc.). Body surface area was subsequently estimated from the measurements of body height and mass (DuBois & DuBois, 1916). Body density was measured using the hydrostatic weighing technique, and used to estimate body fat percentage (Siri, 1956). To determine maximal oxygen consumption, the subjects performed an incremental cycling protocol until exhaustion at a pedalling rate of ∼60–90 revolutions min−1 on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer (Corival Recumbent, Lode B.V., Groningen, Netherlands). The starting workload was set at 100 W for 1 min and was increased at a rate of 20 W min−1 until the subject could no longer maintain a pedalling rate of >50 revolutions min−1. During the incremental exercise, breath-by-breath oxygen uptake was monitored by an automated gas analyser (Medgraphics Ultima, Medical Graphics Corp., St Paul, MN, USA). Maximal oxygen consumption was taken as the highest average oxygen uptake measured over 30 s.

Upon arrival at the laboratory on the days of the experimental sessions, the subjects changed into shorts and running shoes and provided a urine sample. Then they voided their bladder and a measurement of body mass was taken. Subjects were then seated in a semi-recumbent position in a thermoneutral room (∼23°C) and instrumented with four microdialysis fibres (30 kDa cutoff, 10 mm membrane) (MD2000, Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN, USA) on the dorsal side of the left forearm in the dermal layer of the skin. A 25-gauge needle was first inserted into the unanaesthetized skin using an aseptic technique. The entry and exit points were ∼2.5 cm apart. The microdialysis fibre was then threaded through the lumen of the needle, after which the needle was withdrawn leaving the fibre in place. Microdialysis fibres were secured with surgical tape. Each fibre was separated by at least 4.0 cm.

Thereafter, the subjects moved to a thermal chamber (Can-Trol Environmental Systems Ltd, Markham, ON, Canada) regulated to an ambient air temperature of 35°C and a relative humidity of 20%, and rested on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer (Corival Recumbent, Lode B.V). Approximately 20 min after the fibre placement, perfusion of pharmacological agents began via microdialysis. Microdialysis fibres were assigned in a counterbalanced manner to receive (1) lactated Ringer solution (Control), (2) 10 mm ketorolac, a non-selective COX inhibitor (Ketorolac, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), (3) 10 mm NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME, Sigma-Aldrich) to non-selectively inhibit NOS and thus NO production or (4) a combination of 10 mm ketorolac and 10 mml-NAME (Ketorolac +l-NAME). These concentrations were determined based on previous studies in which intradermal microdialysis was employed in human skin (Holowatz et al. 2005, 2009; Kellogg et al. 2005; McCord et al. 2006; Medow et al. 2008; Fujii et al. 2013). The sweating response in humans requires muscarinic receptor activation (Kellogg et al. 1995; Machado-Moreira et al. 2012). It has been suggested that l-NAME has anti-muscarinic effects in rat diaphragmatic microcirculation (Chang et al. 1997). However, the anti-muscarinic effects are still controversial and appear to depend on the tissue type and/or species studied. Importantly, a recent study in humans indicated that 10 mml-NAME induced similar changes (i.e. NO-mediated component) to sweat rate as observed with NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA), which does not have anti-muscarinic effects, during exercise in a hot environment (Welch et al. 2009). Each drug was continuously perfused at a rate of 2.0 μl min−1 with use of a micro-infusion pump (Model 400, CMA Microdialysis, Solna, Sweden) for at least 75 min to ensure the establishment of each blockade. This 75 min plus ∼20 min between fibre placement and the start of drug infusion is probably sufficient for the hyperaemia to subside, i.e. ∼90 min (Hodges et al. 2009). The drug perfusion continued for the entire experimental protocol until the maximal cutaneous vasodilation procedure began (see below).

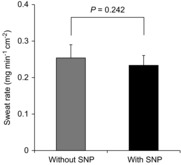

On two separate days, after 10 min of baseline data collection, subjects performed two successive 30-min bouts of semi-recumbent cycling at a fixed rate of metabolic heat production of 400 W (moderate heat load condition, equivalent to 41 ± 3% of maximal oxygen consumption, requiring an external workload of 63 ± 4 W) or 700 W (high heat load condition, equivalent to 68 ± 3% of maximal oxygen consumption, requiring an external workload of 135 ± 4 W). The first and second bouts of exercise were followed by a 20 and 40 min recovery period, respectively. While all ten subjects completed the moderate heat load condition, only eight subjects returned and completed the high heat load condition due to personal reasons and/or exercise intolerance. A fixed absolute heat load was used in the current study to elicit a similar thermal drive for whole-body sweating in all subjects (Gagnon et al. 2013b). After the second 40 min recovery period, administration of 50 mm sodium nitroprusside (SNP; Sigma-Aldrich) at a rate of 3.0 μl min−1 was initiated and continued for 20–30 min to achieve maximal cutaneous vasodilation. To evaluate if an increase in NO bioavailability per se influences sweating, we also monitored local forearm sweat rate at the Control site during the SNP administration for six subjects following the moderate heat load condition. After maximal cutaneous vasodilation was achieved as defined by a plateau for at least 2 min, body mass was measured and a final urine sample was collected.

Measurements

Sweat capsules, each covering an area of 3.8 cm2, were placed directly over the centre of the microdialysis membranes. The sweat capsules were attached to the skin with adhesive rings and topical skin glue (Collodion HV, Mavidon Medical products, Lake Worth, FL, USA). Dry compressed air in the gas tank located in the thermal chamber was supplied to each capsule at a rate of 1.0 l min−1, while water content of the effluent air from the sweat capsule was measured with a capacitance hygrometer (Model HMT333, Vaisala, Helsinki, Finland). Long vinyl tubes were used for connections between the gas tank and the sweat capsule, and between the sweat capsule and the hygrometer so that internal gas temperature was equilibrated to near room temperature (∼35°C) before reaching the sweat capsule (inlet) and the hygrometer (outlet). Local forearm sweat rate was calculated every 5 s from the difference in water content between influent and effluent air multiplied by the flow rate and normalized for the skin surface area under the capsule (mg min−1 cm−2).

Cutaneous red blood cell flux (expressed in perfusion units), which is an index of cutaneous blood flow, was locally measured at a sampling rate of 32 Hz with laser Doppler flowmetry (PeriFlux System 5000, Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden). Integrated laser Doppler flowmetry probes with a seven-laser array (Model 413, Perimed) were housed in the centre of each sweat capsule over each microdialysis fibre, allowing for simultaneous measurement of both local forearm sweat rate and cutaneous red blood cell flux at the four skin sites. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures as well as heart rate were measured every 5 min using an automated blood pressure monitor (Tango+, SunTech Medical Inc., Morrisville, NC, USA) and verified by auditory inspection. Mean arterial pressure was evaluated as diastolic arterial pressure plus one-third of the difference between systolic and diastolic pressures (i.e. pulse pressure). Cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) was evaluated as cutaneous red blood cell flux divided by mean arterial pressure. CVC data were expressed as percentage of maximum as evaluated during the maximal cutaneous vasodilation procedure to minimize the effect of site-to-site heterogeneity in the level of cutaneous blood flow (Minson, 2010).

Oesophageal temperature was measured with a general purpose thermocouple temperature probe (Mallinckrodt Medical Inc., St Louis, MO, USA). The probe was inserted 40 cm past the entrance of the nostril while the subject sipped water (∼200 ml) through a straw. Rectal temperature was also measured using a general purpose thermocouple temperature probe (Mallinckrodt Medical Inc.) inserted to a minimum of 12 cm past the anal sphincter. Skin temperature was measured at ten sites using thermocouples (Concept Engineering, Old Saybrook, CT, USA) attached to the skin with surgical tape. Mean skin temperature was calculated according to proportions determined by Hardy and Dubois (1938) based on local skin temperature measurements at ten sites [forehead (7%), upper back (8.75%), chest (8.75%), bicep (9.5%), forearm (9.5%), abdomen (8.75%), lower back (8.75%), quadriceps (9.5%), hamstring (9.5%) and front calf (20%)]. Temperature data were collected using a data acquisition module (Model 34970A; Agilent Technologies Canada Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada) at a sampling rate of 15 s and simultaneously displayed and recorded in spreadsheet format on a personal computer with LabVIEW software (Version 7.0, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). Due to technical difficulties, one subject did not have corresponding oesophageal (moderate heat load condition) and skin temperature (high heat load condition) measurements.

Indirect calorimetry was used for measurement of metabolic energy expenditure (Nishi, 1981). Expired gas was analysed for oxygen (error of ± 0.01%) and carbon dioxide (error of ± 0.02%) concentrations using electrochemical gas analysers (AMETEK model S-3A/1 and CD3A, Applied Electrochemistry, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Approximately 20 min before the start of baseline data collection, gas mixtures of known concentrations were used to calibrate gas analysers and a 3 litre syringe was used to calibrate the turbine ventilometer. The subjects wore a full face mask (Model 7600 V2, Hans-Rudolph, Kansas City, MO, USA), which was attached to a two-way T-shape non-rebreathing valve (Model 2700, Hans-Rudolph). Oxygen uptake and respiratory exchange ratio were obtained every 30 s and were used to calculate metabolic rate (Nishi, 1981; Kenny & Jay, 2013). Metabolic heat load was estimated from metabolic rate minus external work (i.e. work rate during cycling).

Urine-specific gravity was assessed from the urine samples obtained at the start and end of the experimental protocol in duplicate using a handheld total solids refractometer (Model TS400, Reichter Inc., Depew, NY, USA).

Data analyses

Baseline resting values were obtained by averaging measurements performed over >5 min. Values at the start of intermittent exercise (time 0) were obtained during the last 5 min before exercise commenced. Local forearm sweat rate and CVC as well as core body and skin temperature data acquired during the exercise and recovery periods were obtained by averaging measurements made over the last 5 min of each 10 min interval. Relative changes in CVC (ΔCVC) were calculated as the difference in CVC from the baseline rest to each time point. The heart rate and blood pressure data acquired during the exercise and recovery periods were obtained by averaging the two measurements made over each 10 min interval. Maximal CVC induced with SNP administration at the end of the experimental protocol was determined from averaged CVC data over at least 2 min once a plateau was established. In the moderate heat load condition, local forearm sweat rate at the Control site before (end of second recovery) and at the end of SNP administration was evaluated by averaging values over at least 2 min.

Statistical analyses

The exercise/recovery cycles were defined based on the following time periods: (1) 0–30 min: exercise 1, (2) 30–50 min: recovery 1, (3) 50–80 min: exercise 2 and (4) 80–120 min: recovery 2. Local forearm sweat rate and CVC were analysed using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA within each session with the factors of time (14 levels: rest, 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120 min) and of treatment site (four levels: Control, Ketorolac, l-NAME, and Ketorolac + l-NAME). For the purpose of comparison between different heat load conditions, local forearm sweat rate at the Control site was also analysed using a two-way, mixed model ANOVA with the factors of time (14 levels: rest, 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120 min) and of heat load (two levels: moderate, high). ΔCVC and body temperature and cardiovascular variables were analysed using a two-way, mixed-model ANOVA with the factors of time (six levels: rest, exercise 1 at 30 min, recovery 1 at 20 min, exercise 2 at 30 min, recovery 2 at 20 and 40 min) and of heat load (two levels: moderate, high). Body mass and urine-specific gravity were analysed using a two-way, mixed-model ANOVA with the factors of time (two levels: pre, post) and of heat load (two levels: moderate, high). Moreover, local forearm absolute maximal CVC (expressed in perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100) attained during SNP infusion was analysed with a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA within each session with the factor of treatment site (four levels: Control, Ketorolac, l-NAME, and Ketorolac + l-NAME). When a significant main effect was observed, post hoc multiple comparisons were carried out and corrected to minimize type I error using a Student–Newman–Keuls procedure. Two-tailed Student's paired t tests were also used to compare local forearm sweat rate, local forearm CVC, body temperatures, cardiovascular variables, body weight and urine-specific gravity between heat load conditions, and to compare local forearm sweat rate at the Control site before and at the end of SNP administration during the moderate heat load condition. The level of significance for all analyses was set at P ≤ 0.05. All values are reported as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Body temperatures, cardiovascular responses, and hydration status

Baseline core body (i.e. oesophageal and rectal) as well as skin temperatures, heart rate and mean arterial pressure were all similar between the heat load conditions (all P > 0.216, Table1). However, there was an interaction of heat load and time for oesophageal, rectal and mean skin temperatures, heart rate and mean arterial pressure (all P < 0.002). During the first and second exercise bouts, core body and skin temperatures, heart rate and mean arterial pressure were greater in the high relative to moderate heat load condition (Table1). Furthermore, during the first and/or second recovery, core body temperatures and heart rate were elevated to a greater extent in the high relative to moderate heat load condition (Table1). In contrast, mean arterial pressure was lower at 20 min into the second recovery in the high relative to the moderate heat load condition (Table1).

Table 1.

Body temperatures and cardiovascular variables at rest and during exercises and recoveries

| Rest | Exercise 1 |

Recovery 1 |

Exercise 2 |

Recovery 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 20 min | 30 min | 20 min | 40 min | ||

| Oesophageal temperature, (°C) | ||||||

| Moderate (n = 9) | 37.04 ± 0.09 | 37.43 ± 0.15* | 37.27 ± 0.10* | 37.63 ± 0.13*‡ | 37.44 ± 0.08*‡ | 37.42 ± 0.09*‡ |

| High (n = 8) | 37.19 ± 0.07 | 38.35 ± 0.21*† | 37.60 ± 0.15* | 38.71 ± 0.22*‡† | 37.92 ± 0.16*‡† | 37.71 ± 0.10*† |

| Rectal temperature, (°C) | ||||||

| Moderate (n = 10) | 37.07 ± 0.07 | 37.39 ± 0.07* | 37.37 ± 0.08* | 37.60 ± 0.07*‡ | 37.56 ± 0.07*‡ | 37.53 ± 0.07*‡ |

| High (n = 8) | 37.13 ± 0.08 | 38.03 ± 0.14*† | 38.02 ± 0.25*† | 38.55 ± 0.20*‡† | 38.44 ± 0.26*‡† | 38.11 ± 0.22*† |

| Mean skin temperature, (°C) | ||||||

| Moderate (n = 10) | 34.9 ± 0.13 | 35.5 ± 0.1* | 35.3 ± 0.1* | 35.6 ± 0.1* | 35.3 ± 0.1* | 35.1 ± 0.1* |

| High (n = 7) | 34.96 ± 0.22 | 36.1 ± 0.3*† | 35.5 ± 0.3* | 36.4 ± 0.2*‡† | 35.7 ± 0.3* | 35.2 ± 0.3‡ |

| Heart rate, (b.p.m.) | ||||||

| Moderate (n = 10) | 74 ± 3 | 114 ± 4* | 79 ± 4 | 117 ± 5* | 85 ± 5* | 85 ± 4* |

| High (n = 8) | 71 ± 4 | 161 ± 6*† | 99 ± 5*† | 171 ± 6*‡† | 107 ± 6*† | 101 ± 5*† |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | ||||||

| Moderate (n = 10) | 96 ± 2 | 93 ± 2 | 89 ± 2* | 91 ± 3 | 90 ± 3* | 93 ± 2 |

| High (n = 8) | 93 ± 3 | 101 ± 2*† | 86 ± 2* | 101 ± 3*† | 81 ± 1*† | 87 ± 2* |

Values are means ± SEM. Moderate, session with exercise-mediated heat load of 400 W, High, session with exercise-mediated heat load of 700 W. Temperature values represent an average of the final 5 min of the corresponding period. Heart rate and mean arterial pressure values indicate an average of the final 10 min of the corresponding period.

P < 0.05 vs. Rest.

P < 0.05 Exercise 1 vs. Exercise 2 or Recovery 1 vs. Recovery 2.

P < 0.05 vs. moderate heat load.

A main effect of time (P = 0.002), but no interaction (P = 0.186) or main effect of heat load (P = 0.952), was detected for urine-specific gravity. In particular, subjects were similarly hydrated for both conditions before exercise in the moderate (1.015 ± 0.002) and high (1.012 ± 0.004) heat load conditions (P = 0.483). At the end of the session, subjects were relatively less hydrated, as reflected by an increase in urine-specific gravity in the moderate (1.020 ± 0.002, P = 0.008) and high (1.022 ± 0.002, P = 0.014) heat load conditions. An interaction of time and heat load was measured for body mass (P = 0.004). Body mass decreased during the session by 1.6 ± 0.1% and by 2.2 ± 0.1% following the moderate and the high heat load conditions, respectively (both P < 0.001), with the high heat load condition yielding a greater reduction in body mass (P < 0.001).

Local forearm cutaneous vascular response

Comparison between moderate and high heat load conditions

No interaction of heat load and time (P = 0.107) or main effect of heat load (P = 0.718) was found for local forearm CVC at the Control site. Therefore, no differences in local forearm CVC measured at the Control site were detected between heat load conditions throughout the protocol.

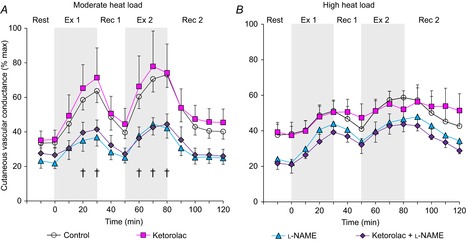

Moderate heat load condition – 400 W

A significant interaction of time and treatment site (P = 0.029) was found for local forearm CVC in the moderate heat load condition. Ketorolac did not change local forearm CVC relative to the Control site (Fig. 1A); however, l-NAME and Ketorolac + l-NAME reduced local forearm CVC in comparison to the Control site to a similar extent at 20 and 30 min into first exercise bout and throughout the second exercise bout (P ≤ 0.05, Fig. 1A). Between-site differences in local forearm CVC were not observed at baseline rest, start of the intermittent exercise (time 0) or at any time point during recovery (all P > 0.297, Fig. 1A). In parallel with the absolute findings, there was an interaction of treatment site and time for ΔCVC (P = 0.018). ΔCVC at the Control site was greater than that at the l-NAME and Ketorolac + l-NAME sites at the end of the first and second exercise bouts (all P < 0.031). Additionally, there was no main effect of treatment site on local forearm absolute maximal CVC (P = 0.335), indicating that local forearm absolute maximal CVC was not different between the treatment sites (Control: 167 ± 16 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100, Ketorolac: 155 ± 12 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100, l-NAME: 206 ± 28 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100, Ketorolac + l-NAME: 191 ± 23 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100). Altogether, we observed NO, but not COX, to be involved in cutaneous active vasodilation during exercise performed at a moderate rate of metabolic heat production (i.e. 400 W).

Figure 1. Local forearm cutaneous vascular conductance.

Time course changes in local forearm cutaneous vascular conductance during exercise at 400 W (moderate heat load) (A, n = 10) and 700 W (high heat load) (B, n = 8) of heat production at four skin sites receiving: (1) lactated Ringer solution (Control, open circles); (2) 10 mm ketorolac (Ketorolac, squares), a non-selective COX inhibitor; (3) 10 mm l-NAME (triangles), a non-specific NOS inhibitor; or (4) combination of 10 mm ketorolac + 10 mm l-NAME (Ketorolac + l-NAME, diamonds). Values are means ± SEM. Each value during exercise and recovery represents the average of the last 5 min of each 10 min interval. Start of intermittent exercise (time 0) indicates resting values 5 min before exercise. Ex 1, first exercise; Rec 1, first recovery; Ex 2, second exercise; Rec 2, second recovery; †Control significantly different from l-NAME and Control significantly different from Ketorolac + l-NAME (P < 0.05).

High heat load condition – 700 W

A main effect of time (P < 0.001) but not of treatment site (P = 0.135) and no interaction of heat load and time (P = 0.659) were measured for local forearm CVC in the high heat load condition. Hence there was no difference in local forearm CVC between treatment sites at any time point from baseline rest to end of second recovery (Fig. 1B). In addition, although a main effect of time was detected (P = 0.029), no main effect of treatment site (P = 0.481) or interaction of treatment site and time (P = 0.826) was observed for ΔCVC. Hence, there were no between-site differences in ΔCVC. Moreover, local forearm absolute maximal CVC did not differ as a function of treatment site (Control: 208 ± 28 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100, Ketorolac: 212 ± 16 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100, l-NAME: 195 ± 14 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100, Ketorolac + l-NAME: 195 ± 18 perfusion units mmHg−1 multiplied by 100, P = 0.659 for a main effect of treatment site). Thus, neither NO nor COX was involved in cutaneous active vasodilation when exercise was performed at a high rate of metabolic heat production (i.e. 700 W).

Local forearm sweat rate

Comparison between moderate and high heat load conditions

There was a significant interaction of heat load and time on local forearm sweat rate (P < 0.001). Specifically, local forearm sweat rate was greater at all time points in the high compared to the moderate heat load condition (all P < 0.018) with the exception of baseline rest, start of the intermittent exercise and the last 10 min of second recovery (all P > 0.072).

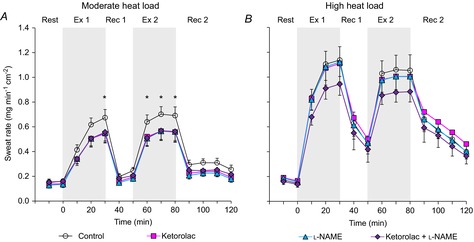

Moderate heat load condition – 400 W

In the moderate heat load condition, an interaction of treatment site and time on local forearm sweat rate was observed (P < 0.001). In particular, local forearm sweat rate was reduced to a similar extent by Ketorolac, l-NAME and Ketorolac + l-NAME compared to Control during the last 5 min of the first exercise and throughout the second exercise (Fig. 2A). However, local forearm sweat rate at baseline rest, start of the intermittent exercise bout and at all time points during recovery was not different between treatment sites (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, local forearm sweat rate measured at the Control site was similar to baseline rest at the end of second recovery (P = 0.260) and no change was observed with the administration of SNP (P = 0.242) (Fig. 3). Therefore, both NO and COX contribute to sweating during exercise performed at a moderate level of metabolic heat production; however, these effects are not additive.

Figure 2. Local forearm sweat rate.

Time course changes in local forearm sweat rate during exercise with metabolic heat production of 400 W (moderate heat load) (A, n = 10) and 700 W (high heat load) (B, n = 8) at four skin sites receiving: (1) lactated Ringer solution (Control, open circles); (2) 10 mm ketorolac (Ketorolac, squares), a non-selective COX inhibitor; (3) 10 mm l-NAME (triangles), a non-specific NOS inhibitor; or (4) combination of 10 mm ketorolac + 10 mm l-NAME (Ketorolac + l-NAME, diamonds). Values are means ± SEM. Each value during exercise and recovery represents the average of the last 5 min of each 10 min interval. Start of intermittent exercise (time 0) indicates resting values 5 min before exercise. Ex 1, first exercise; Rec 1, first recovery; Ex 2, second exercise; Rec 2, second recovery; *Control significantly different from all three sites (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. Local forearm sweat rate with and without SNP.

Local forearm sweat rate receiving lactated Ringer solution at the end of the second recovery (Without SNP, grey bar) or 50 mm SNP (With SNP, black bar) during the protocol to elicit maximal vasodilation in resting subjects (n = 6). Values are means ± SEM.

High heat load condition − 700 W

For the high heat load condition, a main effect of time (P < 0.001) on local forearm sweat rate was observed. However, no main effect of treatment site (P = 0.509) or interaction of heat load and time (P = 0.310) was detected. Subsequently, no differences in local forearm sweat rate were measured between the treatment sites throughout the protocol, indicating that NO- and COX-dependent sweating during exercise is diminished at higher intensities (resulting in rates of metabolic heat production of ∼700 W) (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

The present study examined the separate and combined influence of NO and COX on the cutaneous vascular and sweating responses during intermittent exercise (two bouts) in the heat performed at a moderate (400 W) and high (700 W) rate of metabolic heat production. By using different exercise-induced heat load conditions, we were able to study the separate and combined influence of NO and COX on sweating as a function of increases in the level of hyperthermia (i.e. core body temperature) and the concomitant changes in cardiovascular strain (heart rate and mean arterial pressure). We found that l-NAME reduced cutaneous vascular conductance during intermittent exercise in the moderate but not the high heat load condition. Conversely, Ketorolac did not influence cutaneous vascular conductance during intermittent exercise bouts or post-exercise recovery periods irrespective of heat load. Consistent with our original hypothesis, we found during intermittent exercise bouts performed in the moderate metabolic heat load condition that sweating was similarly reduced by Ketorolac, l-NAME and Ketorolac + l-NAME compared to the Control site, whereas no treatment effect on sweating was detected at a higher metabolic heat load (i.e. 700 W). No treatment effect was found for sweating during post-exercise recovery in either experimental session, which is also consistent with our original hypothesis. Taken together, we show that both NO and COX modulate local forearm sweating during intermittent exercise performed at a moderate rate of heat production (i.e. 400 W) and that the effects of NO and COX are not additive. Our findings also indicate that the contribution of both NO and COX to local forearm sweating is less evident during successive exercise bouts conducted at a higher intensity (e.g. rate of metabolic heat production of 700 W) and during the post-exercise recovery period.

NO- and COX-dependent cutaneous vascular response

Previous studies have identified a role for NO-dependent cutaneous active vasodilation during exercise in temperate (25°C) (McGinn et al. 2014) and warm (30°C) (Welch et al. 2009) ambient conditions. Our findings reaffirmed these reports and extended the influence of NO to include exercise in the heat (35°C) since the administration of l-NAME reduced local forearm CVC during exercise relative to the Control site in the moderate heat load condition (Fig. 1A). By contrast, we could not detect a clear NO-dependent cutaneous active vasodilation during baseline resting in both the moderate and the high exercise heat load conditions (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the difference in baseline CVC between the Control and l-NAME sites by up to ∼20% may be physiologically significant. Indeed, Welch et al. (2009) confirmed that NO contributes to resting cutaneous vascular tone in a warm environment (30°C). However, it should be noted that even when considering the differences at baseline, the NO-dependent cutaneous active vasodilation during exercise in the moderate heat load condition is still evident as ΔCVC from baseline resting to the end of the first and second exercises was greater at the Control site in comparison to that at the l-NAME and the Ketorolac + l-NAME site (see text in the Results for details).

Contrary to the moderate heat load condition, NO-dependent cutaneous active vasodilation was not evident during recovery in either heat load conditions (Fig. 1), which is consistent with our previous study (McGinn et al. 2014). In addition, NO-dependent cutaneous active vasodilation was also not observed during exercise in the high heat condition (Fig. 1B). Although not directly evaluated in the present study, the diminished NO-dependent cutaneous vasodilation during high intensity exercise (i.e. our high heat load condition) may be explained by an increased production of reactive oxygen species (an indicator of oxidative stress). In fact, empirical evidence indicates that increases in oxidative stress can reduce NO-dependent vasodilation in human skin (Holowatz et al. 2006). Moreover, it has been reported that the level of reactive oxygen species increases from resting levels when exercise is performed at moderate to high exercise intensities (i.e. >60% of maximal oxygen consumption) (Wang et al. 2006). Given that the high heat load condition in the present study corresponded to 68 ± 3% of maximal oxygen consumption, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (e.g. superoxide) may have been greater in the high (700 W) relative to the moderate (400 W, only 41 ± 3% of maximal oxygen consumption) heat load condition, which may have impaired NO-dependent cutaneous active vasodilation. Further studies are clearly warranted to elucidate this possibility.

We did not observe COX-dependent cutaneous vasodilation in the forearm during exercise or recovery in either heat load condition as local forearm CVC was not different between the Control and Ketorolac sites (Fig. 1). This is inconsistent with the study by McCord et al. (2006) who showed that Ketorolac reduced forearm CVC compared to a control site during passive heating at rest. Although the reason for this discrepancy is presently unclear, it may indicate different mechanisms underlying the regulation of cutaneous active vasodilation induced by different forms of heat stress (i.e. passive, exercise, post-exercise).

NO- and COX-dependent sweating

Recent studies have implicated NO in modulating sweating during exercise (Welch et al. 2009; Stapleton et al. 2014) but not during post-exercise recovery (Stapleton et al. 2014) in young adults. Consistent with these findings, the present study also demonstrates NO-dependent sweating during both exercise bouts in the moderate heat load condition (Fig. 2A) but not during recovery in either heat load condition (Fig. 2). Interestingly, while local forearm sweat rate during exercise was greater with higher thermal drive, as reflected by higher core body temperature in the high heat load condition (Table1), NO-dependent sweating was diminished in the high heat load condition (Fig. 2B), which may be explained by higher superoxide levels during higher intensity exercise as explained above for cutaneous active vasodilation. The diminished NO-dependent sweating is evident during not only the first but also second exercise bout where local forearm sweat rate tended to decrease in comparison to the first exercise bout (Fig. 2B). This lower tendency may be accounted for by greater percentage reduction in body mass in the high compared to the moderate heat load condition (2.2 vs. 1.6%, respectively) as hypohydration is known to impair the sweating response (Sawka et al. 1985).

The mechanism(s) underlying NO-dependent sweating during exercise in the moderate heat load condition remain(s) unresolved and it is important to mention that an increase in NO per se does not in itself appear to independently increase sweating. Indeed, we found that administration of SNP, an NO donor, did not increase sweating (Fig. 3). Consistent with these observations, Lee and Mack (2006) reported that NO acts to augment cholinergic sweating in humans. Based on our results and those by Lee and Mack (2006), it seems likely that NO has a permissive role in cholinergic sweating rather than acting as an activator of sweat production. Empirical evidence exists to indicate that NO activates Cl− channels in the human lung epithelial cells (Kamosinska et al. 1997), and that NO activates the Na+/K+-ATPase enzyme in the porcine internal mammary artery (Pagan et al. 2010), although no studies in human skin have been conducted. While speculative, NO may increase sweating by stimulating Cl− channels and/or the Na+/K+-ATPase enzyme, both of which are thought to be involved in sweating (Saga, 2002).

Previous studies have reported no effect of a COX inhibitor (taken orally) on the sublingual temperature onset threshold for sweating during passive heating at rest (Charkoudian & Johnson, 1999) or on the mean body temperature onset threshold for sweating during exercise (Bradford et al. 2007). Note, however, that oral administration of a COX inhibitor presents the potentially confounding influence that local COX activity in the sweat gland may not be sufficiently inhibited. In fact, the COX inhibitor can be diluted at various stages following ingestion, including during digestion and subsequent absorption into the blood and interstitial fluid before reaching the target organ (i.e. sweat gland). In the present study, we administered Ketorolac via microdialysis to directly inhibit local COX activity in the dorsal forearm skin region. We observed that, relative to the Control site, Ketorolac impaired forearm sweating during intermittent exercise bouts in the moderate heat load condition (Fig. 2A). By contrast, COX-dependent sweating was not detected during the post-exercise recovery in either heat load condition (Fig. 2). Similarly, an effect of COX inhibition on sweating was also less evident during intermittent exercise bouts in the high heat load condition (Fig. 2B). As explained above, increasing levels of peroxynitrite are produced during higher intensity exercise, which irreversibly blocks biosynthesis of prostacyclin, a product of COX (Zou & Ullrich, 1996). Thus, increased superoxide and thereby peroxynitrite production associated with the high heat load condition may have reduced COX-dependent sweating.

Although we cannot yet define the precise mechanism(s) of COX-mediated sweating in the moderate heat load condition, it may be that prostanoids increase sweating by activating Cl− channels and/or the Na+/K+-ATPase enzyme, both of which are thought to be responsible for sweat secretion as mentioned above (Saga, 2002). Indeed, both prostaglandins E1 and E2 lead to cAMP synthesis as reported in human platelets (Iyu et al. 2011), and cAMP has been shown to activate Cl− channels in the inner medullary collecting duct (Rajagopal et al. 2014) and to up-regulate the Na+/K+-ATPase enzyme in the rat renal cortical collecting duct (Gonin et al. 2001).

Interaction between NOS and COX for sweating during exercise

If NO- and COX-dependent sweating occurs independently, we would expect that inhibiting both enzymes would cause even greater impairments in sweating than either inhibitor alone. However, local forearm sweat rate at the Ketorolac + l-NAME site was similar to that at both the Ketorolac and the l-NAME sites during the moderate heat load condition (Fig. 2A). This may imply that NOS and COX are part of the same pathway and/or may act synergistically. Given the observation that NO increases prostaglandin E2 formation by activating COX in the mouse macrophage cell line (Salvemini et al. 1993), COX-dependent sweating may be influenced by NO and/or NOS. Alternatively, NO-dependent sweating may be due to COX mechanisms as inhibition of COX decreases NOS activity in human platelets (Chen et al. 1997).

Effect of different levels of hyperthermia

Oesophageal temperature, thought to reflect central brain temperature and therefore a critical determinant and/or driver in the regulation of thermoeffector activity, was greater at the end of each exercise in the high relative to the moderate heat load condition (Table1). One might speculate that this higher core body temperature could be associated with greater acetylcholine release from cholinergic nerves, and thus increased activation of muscarinic receptors, which would ultimately result in a diminished role of NO- and/or COX-dependent cutaneous active vasodilation and/or sweating during exercise in the heat. This notion is indirectly supported by the fact that although NO and/or COX contribute to cholinergic sweating and cutaneous vasodilation at low doses of exogenously introduced cholinergic agents (i.e. acetylcholine, methacholine), their contributions are diminished when greater doses are employed (Lee & Mack, 2006; Medow et al. 2008). However, in the study by Welch et al. (2009), NO similarly contributed to cutaneous active vasodilation and sweating from 10 to 30 min of continuous exercise during which core body temperature increased by ∼1.0°C. Along these lines, although oesophageal temperature increased from the first to second exercise bout (Table1), the mechanisms underpinning cutaneous active vasodilation and sweating were similar between the first and second exercise in both the moderate and the high heat load conditions (Figs 1 and 2). Therefore, it seems likely that an increase in core body temperature and perhaps greater muscarinic receptor activation does not substantially modulate the mechanisms of cutaneous active vasodilation and sweating during exercise or recovery, and this response remains intact with successive exercise/recovery cycles.

Limitations

There are two limitations to consider in the present study. First, the insertion of microdialysis fibres in the skin has previously been shown to influence cutaneous vasodilator responses (Hodges et al. 2009). However, it remains unclear whether sweat rate would exhibit a similar effect as a result of microdialysis insertion. Further studies are required to compare sweat rate with and without microdialysis fibres to elucidate this issue. Importantly, we also placed the microdialysis fibres at the Control site with the same perfusion flow rate (2 μl min−1) used at each treatment site. Consequently, any effect of the microdialysis procedure on sweat rate would have been present at each site and therefore would not have impacted between-site comparisons. Second, responses were examined in young males only in the present study. Given recent findings demonstrating age- and sex-related differences in thermoeffector activity (Gagnon et al. 2013b; Stapleton et al. 2014), it remains unclear if a similar pattern of response would be observed in females and/or older adults. With respect to older adults, one previous study shows that older adults may have diminished COX-dependent cutaneous vasodilation (Holowatz et al. 2005). Further studies are needed to elucidate if ageing also reduces COX-dependent sweating.

Clinical perspectives

COX inhibitors (e.g. aspirin, ibuprofen) are commonly prescribed to relieve pain, fever and headache. Furthermore, aspirin is often prescribed to minimize the risk for cardiovascular diseases (Nemerovski et al. 2012). Based on our findings, we speculate that taking COX inhibitors may have some detrimental effect on the whole-body sweating response and thereby impair core body temperature regulation during exercise in the heat. In line with this hypothesis, a recent study demonstrated that oral administration of aspirin increased core body temperature during heat exposure at rest as well as during exercise in the heat in middle-aged adults (Bruning et al. 2013). Given that recent studies reported an effect using a low dose of aspirin (81 mg, taken orally) (Bruning et al. 2013), it may be that even small increases in the concentration of aspirin (and/or other COX inhibitors) in the circulation can impair core body temperature regulation. Due to the common use of such COX inhibitors in the general population, further studies are warranted to address key questions such as (1) which COX inhibitors have a more detrimental effect, (2) what is the minimal dose and frequency necessary to cause impairments in core body temperature regulation and (3) what population is at greatest risk by the use of COX inhibitors (e.g. females, older adults, individuals with chronic disease, and others)?

Conclusion

We show that while an NO-dependent forearm cutaneous active vasodilation occurs during intermittent exercise performed at a moderate rate of metabolic heat production (e.g. 400 W), this response is diminished when exercise is performed at a higher rate of metabolic heat production (e.g. 700 W). We also show that COX is not involved in forearm cutaneous active vasodilation during the successive exercise and recovery periods irrespective of the heat load achieved during exercise. Our results implicate both NO and COX as a modulator of forearm sweating during intermittent exercise performed at a moderate rate of heat production; however, the effects of NO and COX may not be independent. In contrast, the influence of NO and COX on local forearm sweating is diminished during intermittent exercise performed at higher rates of heat production and this attenuation is maintained during the subsequent recovery period.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate all of the volunteer subjects for participating in this study and Martin Poirier for his technical assistance. We thank Mr. Michael Sabino of Can-Trol Environmental Systems Limited (Markham, ON, Canada) for his support.

Glossary

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- CVC

cutaneous vascular conductance

- l-NAME

NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- l-NMMA

NG-monomethyl-l-arginine

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

Key points

Previous studies implicate nitric oxide (NO) in the control of sweating during exercise in the heat; however, it is unclear whether cyclooxygenase (COX) is also involved.

We demonstrated that exercise-induced sweating at a moderate heat production (400 W, ∼40%

was similarly reduced when COX and NO synthase were inhibited separately and in combination.

was similarly reduced when COX and NO synthase were inhibited separately and in combination.

Alternatively, inhibiting COX and/or NO synthase did not influence exercise-induced sweating at a high heat production (700 W, ∼70%

We show that both COX and NO are involved in sweating during exercise at moderate heat production and that the effects may not be independent. However, roles for COX and NO are less evident when heat production is elevated.

The results lead to better understanding of the mechanisms of sweating and indicate that COX inhibitors (e.g. aspirin) may impair core body temperature regulation and thereby increase the risk of heat-related illness.

Additional information

Competing interests

None.

Author contributions

N.F., R.M., J.M.S. and G.P.K. conceived and designed experiments. N.F., R.M., G.P. and R.D.M. contributed to data collection. N.F. performed data analysis. N.F., R.M., G.P., R.D.M. and G.P.K. interpreted the experimental results. N.F. drafted the manuscript. N.F., R.M., J.M.S., G.P., R.D.M. and G.P.K. edited and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All experiments took place at the Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit located at the University of Ottawa.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN-298159-2009 and RGPIN-06313-2014), Discovery Grants Program – Accelerator Supplements (RGPAS-462252-2014) and Leaders Opportunity Fund from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (funds held by G.P.K.). G.P.K. was supported by a University of Ottawa Research Chair Award. N.F. was supported by the Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit. R.M. was supported by a Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology. J.M.S. was supported by the Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit.

References

- Bradford CD, Cotter JD, Thorburn MS, Walker RJ. Gerrard DF. Exercise can be pyrogenic in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R143–149. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00926.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning RS, Dahmus JD, Kenney WL. Alexander LM. Aspirin and clopidogrel alter core temperature and skin blood flow during heat stress. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:674–682. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827981dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buono MJ, Tabor B. White A. Localized β-adrenergic receptor blockade does not affect sweating during exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R1148–1151. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00228.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HY, Chen CW. Hsiue TR. Comparative effects of L-NOARG and L-NAME on basal blood flow and ACh-induced vasodilatation in rat diaphragmatic microcirculation. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:326–332. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charkoudian N. Johnson JM. Altered reflex control of cutaneous circulation by female sex steroids is independent of prostaglandins. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1634–1640. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Salafranca MN. Mehta JL. Cyclooxygenase inhibition decreases nitric oxide synthase activity in human platelets. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1854–1859. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois D. DuBois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Med. 1916;17:863–871. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, Reinke MC, Brunt VE. Minson CT. Impaired acetylcholine-induced cutaneous vasodilation in young smokers: roles of nitric oxide and prostanoids. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H667–673. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00731.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon D, Crandall CG. Kenny GP. Sex-differences in post-synaptic sweating and cutaneous vasodilation. J Appl Physiol. 2013a;114:394–401. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00877.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon D, Jay O. Kenny GP. The evaporative requirement for heat balance determines whole-body sweat rate during exercise under conditions permitting full evaporation. J Physiol. 2013b;591:2925–2935. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.248823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon D. Kenny GP. Exercise–rest cycles do not alter local and whole body heat loss responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R958–968. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00642.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisolfi CV. Wenger CB. Temperature regulation during exercise: old concepts, new ideas. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1984;12:339–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonin S, Deschenes G, Roger F, Bens M, Martin PY, Carpentier JL, Vandewalle A, Doucet A. Feraille E. Cyclic AMP increases cell surface expression of functional Na,K-ATPase units in mammalian cortical collecting duct principal cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:255–264. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JD. Dubois EF. The technic of measuring radiation and convection. J Nutr. 1938;15:461–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges GJ, Chiu C, Kosiba WA, Zhao K. Johnson JM. The effect of microdialysis needle trauma on cutaneous vascular responses in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1112–1118. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91508.2008. (1985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA, Jennings JD, Lang JA. Kenney WL. Ketorolac alters blood flow during normothermia but not during hyperthermia in middle-aged human skin. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1121–1127. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00750.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA, Thompson CS. Kenney WL. Acute ascorbate supplementation alone or combined with arginase inhibition augments reflex cutaneous vasodilation in aged human skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2965–2970. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00648.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA, Thompson CS, Minson CT. Kenney WL. Mechanisms of acetylcholine-mediated vasodilatation in young and aged human skin. J Physiol. 2005;563:965–973. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyu D, Juttner M, Glenn JR, White AE, Johnson AJ, Fox SC. Heptinstall S. PGE1 and PGE2 modify platelet function through different prostanoid receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2011;94:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamosinska B, Radomski MW, Duszyk M, Radomski A. Man SF. Nitric oxide activates chloride currents in human lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L1098–1104. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.6.L1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg DL, Jr, Crandall CG, Liu Y, Charkoudian N. Johnson JM. Nitric oxide and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:824–829. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg DL, Jr, Pergola PE, Piest KL, Kosiba WA, Crandall CG, Grossmann M. Johnson JM. Cutaneous active vasodilation in humans is mediated by cholinergic nerve cotransmission. Circ Res. 1995;77:1222–1228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg DL, Zhao JL, Coey U. Green JV. Acetylcholine-induced vasodilation is mediated by nitric oxide and prostaglandins in human skin. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:629–632. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00728.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny GP. Jay O. Thermometry, calorimetry, and mean body temperature during heat stress. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1689–1719. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. Mack GW. Role of nitric oxide in methacholine-induced sweating and vasodilation in human skin. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1355–1360. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00122.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado-Moreira CA, McLennan PL, Lillioja S, van Dijk W, Caldwell JN. Taylor NAS. The cholinergic blockade of both thermally and non-thermally induced human eccrine sweating. Exp Physiol. 2012;97:930–942. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.065037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord GR, Cracowski JL. Minson CT. Prostanoids contribute to cutaneous active vasodilation in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R596–602. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00710.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn R, Fujii N, Swift B, Lamarche DT. Kenny GP. Adenosine receptor inhibition attenuates the suppression of postexercise cutaneous blood flow. J Physiol. 2014;592:2667–2678. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.274068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medow MS, Glover JL. Stewart JM. Nitric oxide and prostaglandin inhibition during acetylcholine-mediated cutaneous vasodilation in humans. Microcirculation. 2008;15:569–579. doi: 10.1080/10739680802091526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler-Wilson K, Sammons DL, Ossim MA, Metzger NR, Jurovcik AJ, Krause BA. Wilson TE. Extracellular calcium chelation and attenuation of calcium entry decrease in vivo cholinergic-induced eccrine sweating sensitivity in humans. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:393–402. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.076547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minson CT. Thermal provocation to evaluate microvascular reactivity in human skin. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1239–1246. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00414.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Decker K, Reinerth G, Krieg P, Zimmermann R, Heise H, Bayerl C, Marks F. Furstenberger G. Prostaglandin-H-synthase isozyme expression in normal and neoplastic human skin. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:648–656. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990827)82:5<648::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemerovski CW, Salinitri FD, Morbitzer KA. Moser LR. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:1020–1035. doi: 10.1002/phar.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Y. Measurement of thermal balance in man. In: Cena KCJ, editor. Bioengineering, Thermal Physiology and Comfort. New York: Elsevier; 1981. pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pagan RM, Prieto D, Hernandez M, Correa C, Garcia-Sacristan A, Benedito S. Martinez AC. Regulation of NO-dependent acetylcholine relaxation by K+ channels and the Na+-K+ ATPase pump in porcine internal mammary artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;641:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal M, Thomas SV, Kathpalia PP, Chen Y. Pao AC. Prostaglandin E2 induces chloride secretion through crosstalk between cAMP and calcium signaling in mouse inner medullary collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C263–278. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00381.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga K. Structure and function of human sweat glands studied with histochemistry and cytochemistry. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2002;37:323–386. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6336(02)80005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvemini D, Misko TP, Masferrer JL, Seibert K, Currie MG. Needleman P. Nitric oxide activates cyclooxygenase enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7240–7244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K. The mechanism of eccrine sweat secretion. In: Nadel ER, Gisolfi CV, Lamb DR, editors. Exercise, Heat, and Thermoregulation. Dubuqu e, IA: Brown & Benchmark; 1993. pp. 85–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sawka MN, Young AJ, Francesconi RP, Muza SR. Pandolf KB. Thermoregulatory and blood responses during exercise at graded hypohydration levels. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59:1394–1401. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.5.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shastry S, Dietz NM, Halliwill JR, Reed AS. Joyner MJ. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on cutaneous vasodilation during body heating in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:830–834. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki M. Crandall CG. Effect of local acetylcholinesterase inhibition on sweat rate in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:757–762. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.3.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri WE. The gross composition of the body. Adv Biol Med Phys. 1956;4:239–280. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4832-3110-5.50011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhewicz AE, Alexander LM. Kenney WL. Oral sapropterin augments reflex vasoconstriction in aged human skin through noradrenergic mechanisms. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;115:1025–1031. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00626.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JM, Fujii N, Carter M. Kenny GP. Diminished nitric oxide-dependent sweating in older males during intermittent exercise in the heat. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:921–932. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.077644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift B, McGinn R, Gagnon D, Crandall CG. Kenny GP. Adenosine receptor inhibition attenuates the decrease in cutaneous vascular conductance during whole-body cooling from hyperthermia. Exp Physiol. 2013;99:196–204. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JS, Lee T. Chow SE. Role of exercise intensities in oxidized low-density lipoprotein-mediated redox status of monocyte in men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2006;101:740–744. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00144.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch G, Foote KM, Hansen C. Mack GW. Nonselective NOS inhibition blunts the sweat response to exercise in a warm environment. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:796–803. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90809.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BJ. Sensory nerves and nitric oxide contribute to reflex cutaneous vasodilation in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R651–656. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00464.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou MH. Ullrich V. Peroxynitrite formed by simultaneous generation of nitric oxide and superoxide selectively inhibits bovine aortic prostacyclin synthase. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]