Abstract

The myelin content of the cortex changes over the human lifetime and aberrant cortical myelination is associated with diseases such as schizophrenia and multiple sclerosis. Recently magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques have shown potential in differentiating between myeloarchitectonically distinct cortical regions in vivo. Here we introduce a new algorithm for correcting partial volume effects present in mm-scale MRI images which was used to investigate the myelination pattern of the cerebral cortex in 1555 clinically normal subjects using the ratio of T1-weighted (T1w) and T2-weighted (T2w) MRI images. A significant linear cross-sectional age increase in T1w/T2w estimated myelin was detected across an 18 to 35 year age span (highest value of ~ 1%/year compared to mean T1w/T2w myelin value at 18 years). The cortex was divided at mid-thickness and the value of T1w/T2w myelin calculated for the inner and the outer layers separately. The increase in T1w/T2w estimated myelin occurs predominantly in the inner layer for most cortical regions. The ratio of the inner and outer layer T1w/T12w myelin was further validated using high-resolution in vivo MRI scans and also a high-resolution MRI scan of a postmortem brain. Additionally, the relationships between cortical thickness, curvature and T1w/T2w estimated myelin were found to be significant, although the relationships varied across the cortex. We discuss these observations as well as limitations of using the T1w/T2w ratio as an estimate of cortical myelin.

Keywords: myelin, MRI, cortical development, partial volume effect

1. Introduction

Myelin expedites the conduction of electrical signals along axons and is essential for normal, healthy function of the nervous system. While most abundant in the cerebral and cerebellar white matter, significant amounts of myelinated fibers are present in the cortical gray matter. Classic histological studies of postmortem brains by Vogt, Campbell, Elliot Smith (Nieuwenhuys 2013) depict how the distribution of myelinated fibers can vary significantly between cortical regions. Recently, advances of MRI techniques enabled the investigation of the estimated myelin content of the human brain in vivo. Studies have shown that the T1, T2 and T2* relaxation times of the brain tissue depend on the myelin content of the tissue (Bock et al., 2009, 2011, 2013; Geyer et al., 2011; Clark et al., 1992; Barbier et al., 2002; Walters et al., 2003, 2007; Clare and Bridge, 2005; Eickhoff et al., 2005; Bridge et al., 2005; Sigalovsky et al., 2006; Dick et al., 2012, Cohen-Adad et al., 2012; Lutti et al., 2013, Stüber et al., 2014). Using the ratio of T1- and T2-weighted (T1w and T2w) image intensities, Glasser & Van Essen (2011) detected the boundaries of myeloarchitectonically distinct cortical regions. Their method has subsequently been applied to link estimated cortical myelin content to cognitive performance and also to investigate the lifelong effect of age on cortical myelination (Grydeland et al., 2013). The myelin density map calculated from the ratio of T1w and T2w images has also been found to show significant correlation with the retinotopic map of the occipital cortex (Abdollahi et al., 2014).

The present paper builds on this prior work and explores a partial volume correction as applied to a large uniformly collected dataset. MR images common in biomedical research are subject to partial volume effect in which the intensity of the cortical gray matter (GM) can be contaminated by intensities of local white matter (WM) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Here we introduce a partial volume correction algorithm to correct for this effect, and apply our technique to quantify the T1w/T2w intensity ratio as an estimate of myelin map (T1w/T2w myelin) of 1555 clinically normal 18 to 35 year old subjects using 1.2 mm isotropic voxel MRI.

It is important to note that T1w/T2w estimated myelin is not a pure measure of myelin but nonetheless an MR-accessible proxy. The ratio of the T1w and T2w images of a subject provides a unitless quantity that correlates with cortical myelination (Glasser and Van Essen, 2011, 2013; Grydeland et al., 2013) but does not provide an absolute measure of myelin density. Also, iron, in addition to myelin, has been found to contribute to cortical MR image contrast. However, it has been shown that iron and myelin are often colocalized in the cortex (Fukunaga et al., 2010). Therefore, while we do not expect myelin to be the only factor contributing to the T1w/T2w image intensity ratio, a large fraction of the variation in T1w/T2w is likely due to variation in myelin density (more details in section 4.1).

With these caveats in mind, we (1) quantified partial volume effect on T1w/T2w myelin measurement, (2) used our technique to investigate the vertical distribution of myelin in the cortex, (3) quantified the effect of age on T1w/T2w myelin, and (4) investigated the relationship between cortical thickness, curvature and T1w/T2s myelin. We compared our results with high resolution in vivo MRI scans of five subjects and also a postmortem ex vivo brain scan to ensure that the difference in inner and outer layer myelination detected in the main dataset was not an artifact of mm-scale voxel size.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Main Dataset

1555 clinically normal, English-speaking subjects with normal or corrected-to-normal vision aged 18 – 35 years (mean age = 21.2 years, standard deviation = 3.0 years, 43.3% male) were included. Participants were recruited from universities around Boston, the Massachusetts General Hospital, and the surrounding communities. The subjects were acquired as part of the Brain Genomics Superstruct Project (http://neuroinformatics.harvard.edu/gsp) and subsets of the data have been published previously (e.g., Yeo et al., 2011; Holmes et al., 2012). Initially 1800 subjects were divided into two age and gender matched groups of 900 to check replicability of results. Subjects were excluded if fMRI signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was below 100 (Yeo et al., 2011; Van Dijk et al., 2012), or if manual inspection of the MR images showed artifacts (the fMRI quality assessment was not specific to the structural images but allowed a general means to exclude participants with high motion). Quality control steps reduced the number of subjects in the two groups to 773 and 782 and results are reported only for these 1555 subjects. For 99 of these subjects, two separate scanning sessions were processed independently to check test-retest reliability of the results. Participants provided written informed consent in accordance with guidelines of the Harvard University and Partners Health Care institutional review boards.

All images for the main dataset were collected on matched Siemens 3T Tim Trio scanners at Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital using the vendor-supplied 12-channel phased-array head coil. Data included bandwidth-matched T1w and T2w images for each session of each subject. T1w images were acquired using high-resolution multi-echo MPRAGE protocol (TR = 2200 ms, FA = 7°, 1.2 × 1.2 × 1.2-mm voxels, and FOV = 192 × 192). In this method (van der Kouwe et al., 2008) four structural scans are obtained (with TE values of 1.54, 3.36, 5.18 and 7.00 ms) over the same timespan as a conventional scan. This was achieved by using a much higher bandwidth than is usual in MPRAGE. Each subject’s T2w image was acquired with 3D T2-weighted high resolution turbo-spin-echo (TSE) with high sampling efficiency (SPACE, Lichy et al., 2005) in the same scanner during the same session as the T1w image with TR = 2800 ms, TE =327 ms, 1.2 × 1.2 × 1.2-mm voxels, and FOV = 192 × 192. Multi-echo MPRAGE T1w image acquisition allowed bandwidth matching of the T1w and T2w images (both acquired with 651 Hz/pixel). The matched bandwidth, spatial resolution and FOV of the T1w and T2w image of each subject implies that there is no differential distortion between the image types, allowing direct superposition and comparison of the two images. In conventionally acquired T1w images different brain regions would suffer different levels of distortion for T1w and T2w images and the images would not register properly everywhere.

2.2 High Resolution Data

In addition to the main dataset, high-resolution T1w in vivo scans (Siemens Magnetom 3T scanner, MPRAGE sequence, 500 µm isotropic voxels, TR = 2530 ms, TE = 4.85 ms, flip angle 7°) of five subjects (mean age = 26.6 years, standard deviation = 4.8 years, 80% female) and a T2w ex vivo scan (Siemens Magnetom 7T scanner, FLASH sequence, TE = 9.39 ms, TR = 22 ms) of a postmortem brain (male, 60 year old at time of death) with 200 µm isotropic voxels were used to investigate two-layer myelination.

2.3 MRI Data Preprocessing

Each subject’s T1w image was processed using the FreeSurfer version 4.5.0 software package (RRID:nif-0000-00304) pipeline, which is freely available online (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). The software package reconstructs an individual’s cortical surface from the subject’s T1w structural scan. Processing included the following steps: correction of intensity variations due to MR inhomogeneities (Dale et al. 1999), skull stripping (Ségonne et al. 2004), segmentation of cortical gray and white matter (Dale et al., 1999), separation of the two hemispheres and subcortical structures (Dale et al. 1999, Fischl et al., 2002, 2004) and eventually construction of smooth representations of the gray/white interface and the pial surface (Dale et al., 1999). After reconstruction of the individual’s cortical surfaces, correspondence between the individual’s gyral and sulcal pattern and that of an average brain was calculated (Fischl et al. 1999a, Fischl et al. 1999b). This information was later used to bring the individual myelin maps to a common surface for comparison.

2.4 Partial Volume Correction (PVC) and T1w/T2w Myelin Map Estimation

We define the T1w/T2w estimated myelination of a region as the ratio of the PVC GM intensities of the T1w and the T2w images in that region. First, the 1.2-mm voxel resolution raw T1w and T2w data was resampled to 1-mm isotropic voxels. Next, the T2w image of each subject was aligned to the T1w image using boundary-based registration (Greve & Fischl 2009). For the two-layer analysis, an intermediate surface was generated at mid-thickness of the cortex using a novel surface deformation algorithm (Polimeni et al, 2010). Only the T1w image was used for surface construction and the generated surfaces were used with both the T1w image and the T2w image aligned to the T1w image. Next, PVC GM intensities were calculated as follows.

The intensity of a voxel of a T1w or a T2w image is due to signals from various tissue classes that might occupy the voxel. Voxels that intersect the pial surface contain both GM and CSF whereas those that intersect the white surface contain GM and WM. To calculate the partial volume corrected intensity of GM we assumed a linear forward model in which the observed image intensity I(x) at location x, is a combination of true, unobservable intensities Ic for tissue class c, for each of C tissue classes (typically, GM, WM and CSF but also inner and outer GM for the two-layer analysis):

| (1) |

where is the fraction of the voxel at location x that is occupied by tissue class c. We estimated fc(x) by forming a high-resolution volume (typically 0.125mm isotropic) so that every 1-mm voxel of the T1w and T2w images contained 83 = 512 high-resolution voxels. The interior of each surface compartment was then filled in this high-resolution space to form high-resolution binary volumes. Boolean operations on these volumes then yielded the different compartments we are seeking (e.g. the single-layer GM compartment is computed as voxels that are interior to the pial surface and NOT interior to the white surface and an inner cortical layer mask is computed as voxels that are interior to the intermediate mid-gray surface and NOT interior to the white surface). The volume fractions fc(x) were computed by simply counting the number of high-resolution voxels in each tissue class that were 1 in each low-resolution voxel. Supplementary Figure 1 (Inline Supplementary Figure 1 here) shows this methodology for a simplified two-dimensional case where each 1-mm voxel is divided into four high-resolution voxels. We then assumed the true intensities Ic are constant in a small neighborhood N(x) around each voxel, and compiled a set of linear equations that made inverting equation (1) well-posed. That is, we found at least C nearby locations in which fc(x')>T,x' ∈ N(x) for some small threshold T (we used T = 0.3) for every class c so that Ic could be estimated accurately using a pseudoinverse. Solving this linear system resulted in estimates of GM (single layer or two-layer), WM and CSF intensities with less contamination from other tissue classes. The corrected estimate of the intensity of each tissue class was then sampled onto the surface vertices using trilinear interpolation.

Next, each subject’s PVC T1w GM intensity at each surface vertex was divided by the subject’s T2w GM intensity at the vertex to obtain the subject’s all-surface PVC myelin map (single-layer and two-layer). These myelin maps were next projected to the average surface (FreeSurfer “fsaverage” surface for mean myelin map, FreeSurfer “fsaverage5” surface for correlation analysis) for group comparison.

As an alternate approach the ratio of the raw T1w image and the aligned T2w image was calculated first followed by partial volume correction and estimation of the GM T1w/T2w image intensity ratio. The results obtained using this approach were very similar to those from the first approach as expected, since the T2w images was aligned to the T1w image. In this work the first approach was used for all calculations. All sample-averaged estimated myelin maps shown in this work were smoothed with a surface-based kernel of full-width-half-max (FWHM) value of 5 mm. Individual myelin maps used for correlation and regression analysis were smoothed with a 10 mm FWHM kernel to improve signal to noise ratio.

Additionally, results for T1w/T2w estimated myelin maps were calculated without PVC for comparison when relevant (Figures 1, 2 and 3). These “no-PVC” myelin maps were calculated using the FreeSurfer function mri_vol2surf: the mean intensity of cortical GM was measured along the normal at each vertex of the subject’s reconstructed white surface. This function does not correct for partial volume effect.

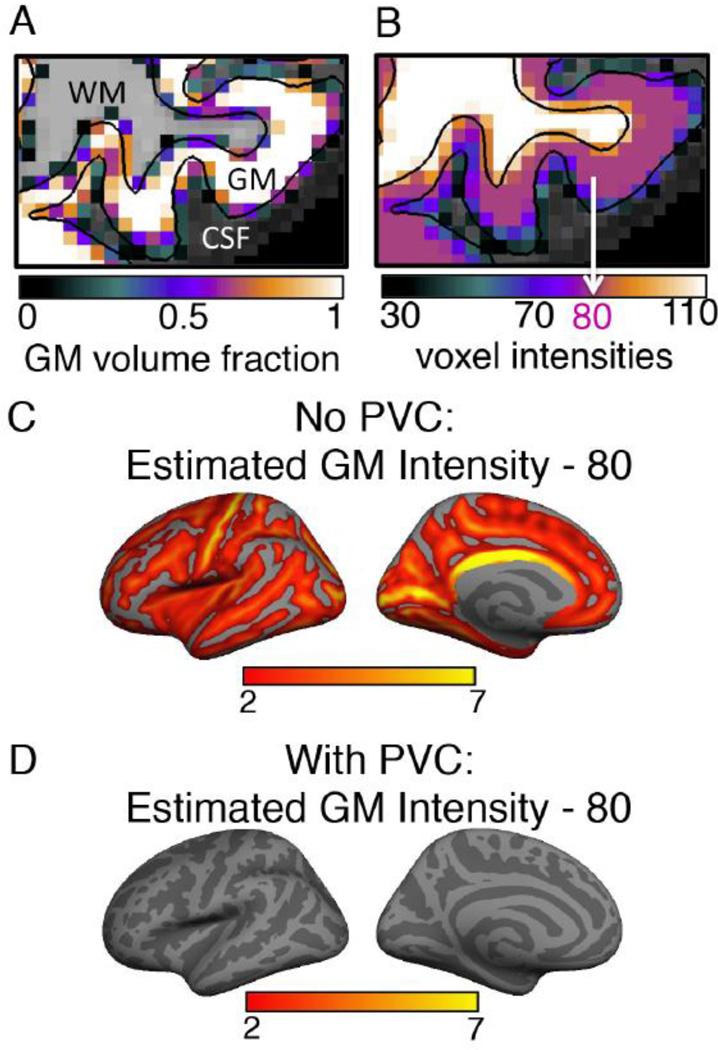

Figure 1. Need for partial volume correction.

A: GM volume fractions of the voxels of the cortical ribbon overlaid on a T1w image. The pial and the white surfaces are shown using black lines and the mostly white region between the two black surfaces in this figure represents the GM ribbon. The colors of the voxels in the GM ribbon represent the volume fraction occupied by GM. Hence, the voxels in the middle of the ribbon have a value of 1 whereas those near the WM or CSF boundary have values < 1. The voxels completely within WM or CSF are shown in shades of gray. The color scale applies only to the GM voxels. B: Same T1w image region showing the simulation intensity values of the voxels (section 2.7). In the simulation GM, WM and CSF were assumed to have constant values of 80, 110 and 30, respectively. Each voxel in the GM ribbon was assigned an intensity value using its volume fraction values and eq. (2). C: Difference map of GM intensity calculated without partial volume correction (no-PVC) and the actual assigned GM value of 80 (in corrected T1w image intensity units) of the simulated volumes. Non-zero value implies erroneous estimation of assigned GM intensity. The error is found to be larger in the sulci compared to the gyri. D: Difference between measured GM intensity using the PVC method and the assigned GM intensity value of 80 of the simulated volumes. The PVC method does a near-perfect job of estimating the assigned GM intensity value. The light and dark gray pattern on the surface shows the gyral pattern of the FreeSurfer (fsaverage) surface, light gray representing gyri and dark gray the sulci.

Figure 2. Single-layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin map.

The mean single-layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin map of 1555 clinically normal subjects aged 18 to 35 years is shown. Each subject’s single layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin map was z-transformed (to indicate the deviation of each vertex from the mean value across the cortex, calculated by zvert = (x – M)/s, where zvert is the z-score at a vertex, x is the T1w/T2w value at the vertex and M and s are the mean and the standard deviation of the T1w/T2w values of all the vertices in both hemispheres) and the sample-averaged maps of GRP1 (N = 773) and GRP2 (N = 882) are shown for both the PVC and the no-PVC methods. On the z-score scale positive and negative values correspond to higher and lower than average T1w/T2w values, respectively. A: PVC myelin map for GRP1, B: no-PVC myelin map for GRP1, C: PVC myelin map for GRP2 and D: no-PVC myelin map for GRP2. For both methods, the mean T1w/T2w myelin maps of the two groups are very similar. In all 4 panels, the primary sensory areas display high T1w/T2w myelination and the association areas show low T1w/T2w values. Compared to the no-PVC method, the PVC method estimated higher myelination in the superior parietal cortex and lower myelination in the association auditory cortex area. However, it should be noted that due to z-score normalization this figure only allows comparison of relative T1w/T2w ratios of different cortical regions. A more direct difference map is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Difference between PVC and no-PVC T1w/T2w estimated myelin maps.

The mean difference between the no-PVC and the PVC T1w/T2w estimated myelin maps of the 1555 subjects is shown. Each subject’s individual PVC T1w/T2w map was subtracted from the subject’s no-PVC T1w/T2w map and the sample-averaged percentage difference map was calculated. Widespread statistically significant differences were detected (FDR, q = 0.01) across the cortex. The no-PVC method T1w/T2w value was higher than the PVC T1w/T2w value in most cortical regions. The difference was larger in the sulci (> 15%) compared to the gyri. The pattern of difference was found to be very similar to the simulated difference map shown in Figure 1C.

2.5 Processing of the high resolution data

Five surface ROIs were chosen based on the results of the two-layer T1w/T2w myelin map of the main dataset (section 3.3) for comparison with the high-resolution data. Two-layer myelin maps were created using the T1w images of the five high-resolution (500 µm isotropic voxels) in vivo scans. These maps were used to calculate the ROI-averaged values of inner to outer layer myelin for comparison with the main dataset results. Additionally, these ROIs were mapped to a high resolution (200 µm isotropic voxels) T2w ex vivo scan of a postmortem brain using spherical morphing to create volumetric snapshots corresponding to these surface ROIs for qualitative comparison with the main dataset results. The volumetric snapshots were generated by finding the center of the predicted region, and then taking a zoomed in snapshot in the orientation most perpendicular to the cortical surface.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Matlab V 8.0 (R2012b). Correlation analysis results presented were calculated using the “partialcorr” or “corr” function, as relevant. Linear regression to investigate the effect of age was performed using the Matlab “regress” and “regstats” functions. Correlation and regression coefficients were considered to be significant and shown in figures after False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction with q = 0.01 unless specifically stated as otherwise. Age, gender, handedness, scanner location, console version and intra-cranial volume (ICV; eTIV in Buckner et al., 2004; an atlas based spatial normalization procedure) were regressed out in the correlation analysis of thickness, and curvature with T1w/T2w myelin. For the analysis of the effect of age on T1w/T2w myelin, all these covariates excluding age were regressed out.

2.7 Simulation

To investigate the difference between the image intensities measured by the PVC and the no-PVC methods, we simulated “test brains” for 50 subjects. For this, the voxels of each subject’s T1w image were assigned custom intensity values under the assumption of constant intensities of GM, WM, and CSF across the brain. Each voxel was assigned a value that was a linear combination of the different tissue intensities weighted by the voxel’s volume fraction for each tissue type as calculated from the actual T1w image of each subject using methods described in section 2.4. We assigned GM, WM and CSF constant intensity values of 80, 110, and 30, respectively, (typical values for FreeSurfer processed T1w images), and voxels were assigned intensity using the following formula:

| (2) |

where I is the intensity of a voxel, and fWM, fGM and fCSF are the volume fraction values of the voxel for WM, GM and CSF, respectively. Accurate measurement of GM intensity in these brains would correspond to a constant value of 80 at every vertex on the cortical surface. Any deviations would be considered as erroneous.

3. Results

3.1 Partial Volume Effect Correction: Simulation Results

MR images that are commonly used in biomedical research have mm-scale resolution and voxels at the cortical surface boundaries (gray/white and gray/cerebrospinal fluid) contain varying amounts of non-GM tissues. Since the ratio of GM intensity of a subject’s T1w and T2w images is the measurement of interest in this technique, intensity contributions from other tissues such as WM and CSF need to be accounted for in order to measure the GM intensity accurately. A typical example of partial volume effect can be seen in Figure 1A which shows GM volume fractions of the cortical ribbon voxels superposed on a T1w image. The mostly white region between the two black surfaces in this figure represents the GM ribbon. The colors of the voxels in this GM region represent the volume fraction occupied by GM. Hence, the voxels in the middle of the ribbon have a value of 1 whereas those near the WM or CSF boundary have values < 1. Corrections need to be made to compensate for this partial volume effect for an accurate estimation of the intensity due to GM alone.

Details of our correction method can be found in section 2.4. To check the effectiveness of our approach, we applied our algorithm to simulated T1w images (section 2.7) with known GM, WM and CSF intensities. The assigned cortical GM intensity for these volumes was 80 (Figure 1B). Voxel-wise intensity values were assigned by weighing this value with partial volume fraction using equation (2). Figure 1C and Figure 1D show the mean difference between measured GM intensity and the actual value of 80 for the two methods. Our PVC method accurately estimated the assigned GM intensity (Figure 1D), whereas the no-PVC method overestimated the assigned GM intensity (Figure 1C). The no-PVC error was larger in the sulci with maximum value of ~10%. These simulation results imply that without partial volume correction mean intensity of the GM ribbon is overestimated in most cortical regions.

3.2 Single Layer T1w/T2w Myelin map

The single layer T1w/T2w myelin map was estimated from the mean PVC T1w/T2w ratio of the GM ribbon at each vertex. The technique provided a T1w/T2w value for each vertex of the cortical surface. For each subject we converted this individual T1w/T2w ratio myelin map to an individual z-score map using a z-transformation so that the value at each vertex indicates the deviation of the T1w/T2w value at the vertex from the mean T1w/T2w value of all the vertices in both hemispheres. The mean z-score map of the sample is presented as the cortical mean myelin map in Figure 2. To check replicability of our results, we divided the subjects into two age- and gender-matched groups (GRP1, N = 773 & GRP2, N = 782, details in section 2.1). Figures 2A and 2C show the PVC method averageT1w/T2w maps for GRP1 and GRP2 and Figures 2B and 2D show the average maps of the same groups without PVC. The blue and red/yellow areas in these z-score maps correspond to cortical regions with lighter and heavier than average T1w/T2w values, respectively. We found the estimated mean T1w/T2w myelin maps of GRP1 and GRP2 to be nearly identical for both methods (r = 0.999, p ~ 0 for both PVC and no-PVC). The no-PVC T1w/T2w myelin maps (Figures 2B and 2D) are very similar to the T1w/T2w myelin maps of Glasser & Van Essen (2011) and Glasser et al. (2013). Consistent with their results, we observed high T1w/T2w myelination in the motor and somatosensory strip, visual cortex, auditory cortex, posterior cingulate and some regions of the temporal and the parietal lobes in both our PVC and no-PVC myelin maps. Also consistent with their findings, the lowest T1w/T2w myelination regions in all four of our maps are located in the anterior insula, temporal pole, prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex.

However, the PVC and the no-PVC maps differed in some regions. The difference map obtained by subtracting the sample average (N = 1555) PVC map from the average no-PVC map (without z-transformation) is shown in Figure 3. The no-PVC method displayed an increased T1w/T2w intensity ratio over much of the cortex particularly in the sulci, where the effect was as large as 20%. The error pattern closely followed the simulated difference pattern shown in Figure 1C.

Data from two independent scan sessions were available for 99 subjects. To assess the reliability of the single layer PVC T1w/T2w myelin map we processed each session of these 99 subjects independently and estimated the myelin map for each subject for each session. These were used to calculate between-session correlation across all the surface vertices for each subject resulting in a mean Pearson correlation of r = 0.83 (std = 0.03) for all 99 subjects. Additionally, 39 of these 99 subjects were scanned in the same scanner and with the same console version during both sessions. Using the T1w/T2w myelin maps for these subjects we calculated the between-session absolute percentage difference at each vertex. The sample average map of the percentage difference is shown in Supplementary Figure 2 (inline Supplementary Figure 2 here). Averaged over all surface vertices the mean between-session percentage difference was found to be 3.3% with a standard deviation of 0.7% with a maximum value of 9%.

3.3 Two-Layer T1w/T2w Myelin Map

Partial volume corrected myelin maps were created for the inner and the outer gray matter layers (Materials and Methods) by estimating the T1w/T2w intensity ratio of each layer separately. The aim of this analysis was to quantify the spatial properties of the laminar distribution of myelin density of the cortex within the limitation of the data. It should be noted that the division of the cortex into two broad layers does not divide the cortex at a classical laminar boundary, and may cut through different layers (e.g., III vs. IVB) in different cortical regions.

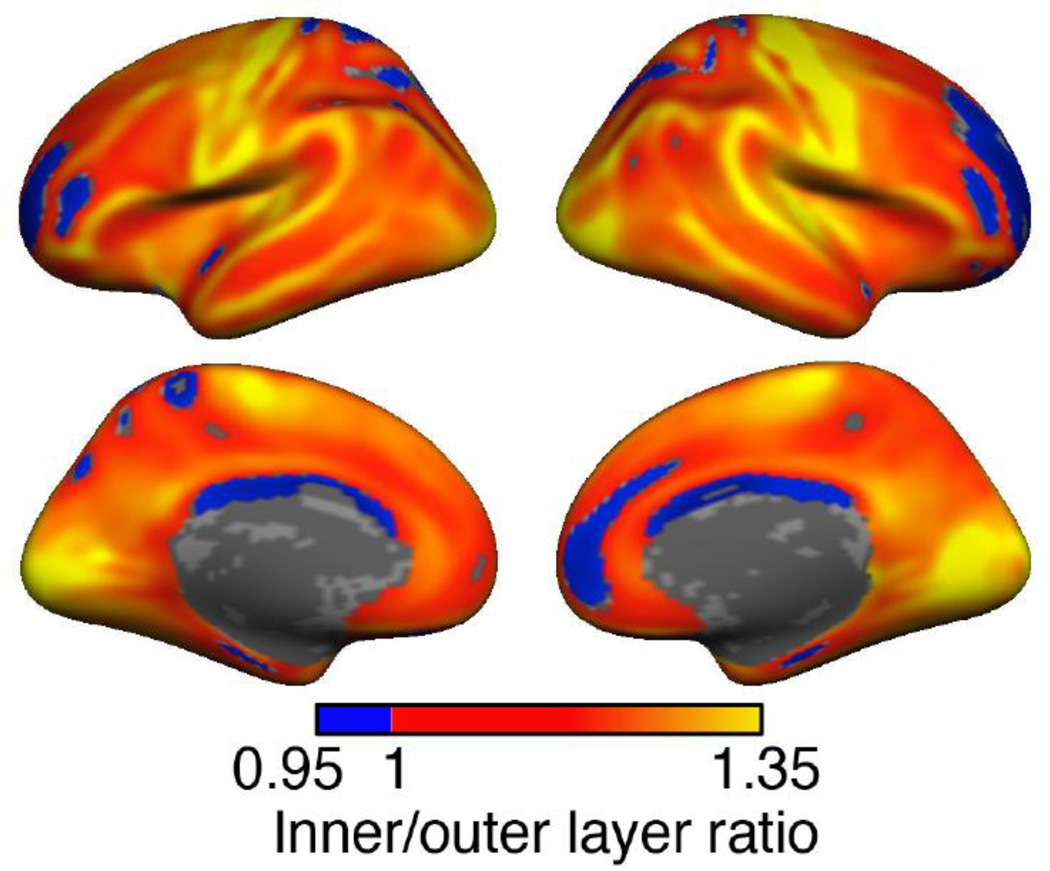

Figure 4 shows the map of the ratio of T1w/T2w myelin of the inner and the outer layer averaged for all 1555 subjects. A value greater than unity indicates higher T1w/T2w myelination in the inner layer compared to the outer layer and a value less than unity corresponds to higher myelination in the outer layer. The inner cortical layer displayed higher T1w/T2w value almost everywhere in the cortex except in the prefrontal and the superior parietal regions, where the value was about 95% of the T1w/T2w value of the outer layer. The regions that were found to be heavily myelinated in the single layer analysis were also found to be more heavily myelinated in the inner layer compared to the outer layer (e.g. visual, motor, and somatosensory cortices). In the vast majority of the cortex the inner layer T1w/T2w value was 10% - 20% higher than the outer layer T1w/T2w value. GRP1 and GRP2 showed nearly identical ratio maps (r = 0.998, p ~ 0) in this calculation also, and are not shown separately.

Figure 4. Ratio of inner and outer layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin.

Our algorithm was used to create a mid-thickness cortical surface and PVC corrected T1w/T2w estimated myelin maps were calculated for each layer separately. The sample-averaged ratio of inner layer and outer layer T1w/T2w myelin values are shown here. The inner layer was found to be more heavily myelinated (ratio > 1) than the outer layer almost everywhere in the cortex, except in some regions of the prefrontal, parietal and cingulate cortices. In these areas, the ratio was ~ 0.95. At each vertex a t-test was performed to test the difference between the inner and the outer layer T1w/T2w values. Only vertices with statistically significant (FDR, q = 0.01) differences between the inner and the outer layer T1w/T2w values are shown.

Since the thinnest parts of the cortex (e.g., visual cortex) were often covered by only a single voxel in our main dataset, we next investigated the possibility that these results might be somehow due to the resolution of the data. We selected two ROIs with low inner to outer layer ratio of T1w/T2w myelin (ROIs 1 and 2 in Figure 5A) and three ROIs with high inner to outer layer ratio of T1w/T2w myelin (ROIs 3, 4 and 5 in Figure 5A) for comparison with higher resolution in vivo MRI scans of five subjects. The ROI-averaged inner to outer layer ratios of T1w/T2w myelin of the main dataset are shown in Figure 5C. Only T1w images were available in the high-resolution in vivo dataset and we show the ROI-averaged ratios of the inner and outer layer PVC T1w image intensity values of these subjects in Figure 5B. Consistent with the main dataset results, ROIs 1 and 2 displayed lower values compared to ROIs 3, 4 and 5 in the high-resolution data as well. However, the actual value of the ratio of inner and outer layer myelin for each ROI was slightly different in the two datasets. Also, the overall difference between the ROIs was smaller in the higher-resolution dataset (range ~ 1.06 – 1.15) compared to the main dataset (range ~ 1 – 1.25). The quantitative difference between the results shown in Fig. 5B and Fig. 5C possibly arises from the fact that although the T1w image intensity is correlated with cortical myelin content, it is a different measure compared to the T1w/T2w intensity ratio. Additionally, differences in the scanning parameters between the two datasets makes qualitative comparison of the relative myelination of the ROIs within each dataset more meaningful than direct comparison of the exact value of each ROI in the two datasets.

Figure 5. ROI-based analysis of inner and outer layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin.

A: Five ROIs selected for comparison with high-resolution data are shown in green superposed on the left hemisphere of Figure 4. ROIs 1 and 2 were chosen from regions with low inner to outer layer myelin ratio and ROIs 3, 4 and 5 were chosen from regions with high inner to outer layer myelin ratio in our main dataset. B: bar plot showing ROI-averaged inner and outer layer ratio of PVC myelin calculated from the high-resolution (500 µm isotropic voxels) T1w images (section 2.2). C: bar plot showing ROI-averaged inner and outer layer ratio of PVC T1w/T2w estimated myelin in the main dataset. In both B and C red dots were used to indicate individual subject’s values. Standard errors of the mean are shown using green lines.

Additionally, Figure 6 shows T2w images of these five ROIs in a high-resolution (200 µm isotropic voxels) ex-vivo MRI scan. The highly myelinated Stria of Gennari of the primary visual cortex is clearly visibly in ROI 5. Although all six cortical layers are not differentiable in this ROI, the GM closer to the WM clearly appears to have lower T2w intensity compared to the GM in the outer cortical region, possibly implying heavier myelination of the GM below the Stria of Gennari compared to the GM above it. Although no clear lamination is visible in the other four ROIs, the increase of T2w intensity (hence possible decrease of myelination) of the GM from the inner to the outer boundary of the cortical ribbon is more prominent in ROIs 3 and 4 compared to ROIs 1 and 2. These results are qualitatively consistent with the results of the main dataset in which ROIs 1 and 2 were found to show comparable inner and outer layer T1w/T2w myelin values whereas ROIs 3, 4, and 5 were found to be regions with higher T1w/T2w myelination of the inner layer compared to that of the outer layer.

Figure 6. ROI analysis in high-resolution postmortem brain.

ROIs shown in Figure 5A were projected on a high resolution (200 µm isotropic voxels) scan of a postmortem brain. The numbers in the different panels indicate the ROI number (Figure 5A). The scan is T2-weighted and hence lower intensity corresponds to heavier myelination.

3.4 Cortical Thickness, Curvature and T1w/T2w Myelination

Just as the estimated myelination pattern of the cortex varies in different regions, so do cortical thickness and curvature. Higher myelin density in a region could be due to a higher number of myelinated axons, or due to the axons being more myelinated than in other regions. Both situations could also make the cortex thicker, creating a correlation between cortical myelination and thickness. Additionally, it has been shown that cortical curvature is correlated with both myelination (Annese et al., 2004; Sereno et al., 2013) and thickness (Fischl and Dale, 2000; Sigalovsky et al., 2006; Sereno et al., 2013). For these reasons the relationship between cortical thickness, curvature and T1w/T2w ratio was investigated using our large sample.

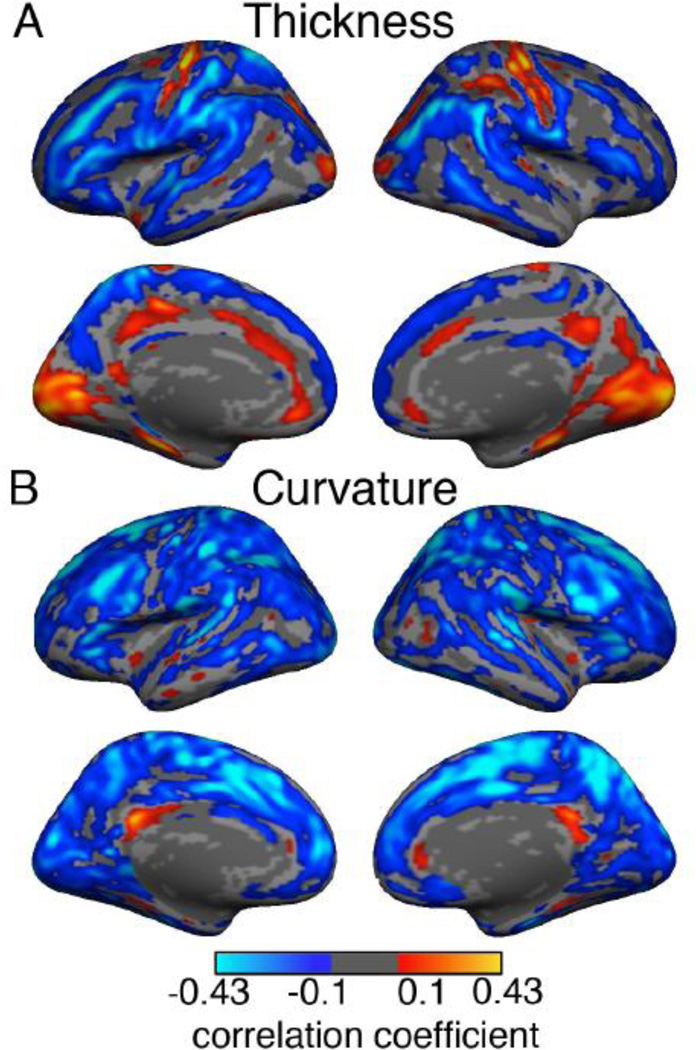

First, the individual level correlation between T1w/T2w estimated myelination, thickness and curvature was explored at each vertex of the cortex. The correlation between myelination and thickness was calculated by controlling for curvature and the correlation between myelination and curvature was computed using thickness as a controlled parameter. For the 1555 subjects, the mean all-cortex correlation between T1w/T2w myelin and thickness was r = −0.32 ± 0.07 (mean +/− std), with mean p-value = 3 × 10−6 and that between curvature and myelination was r = − 0.34 ± 0.07, with mean p-value < 10−39. This implies that when cortical regions of similar curvature are compared, thinner regions tend to have higher T1w/T2w myelination compared to thicker regions and that when regions of similar thickness are compared, the more convex regions tend to have higher T1w/T2w myelination than the more concave regions. These results are consistent with the results of Sereno et al. (2013) who showed that more convex regions have higher R1 values (R1=1/T1, their measure of myelin) compared to more concave regions and that the relationship between R1 and curvature survived even after regressing out cortical thickness.

Next the pattern of correlation between these quantities was investigated at each surface vertex across our sample of 1555 subjects. Both positive and negative correlations were found between T1w/T2w myelin and thickness as shown in Figure 7A. Positive correlations were detected in the central sulcus, somatosensory cortex (right hemisphere), primary visual cortex, parahippocampal cortex and parts of the cingulate cortex. Negative correlations were found extensively along the gyri: pre and post-central, superior-parietal, supra-marginal, superior- and middle-temporal, middle-frontal, pars-triangularis, superior-frontal and the precuneus. Only correlations that survived a False Discovery Rate (FDR) with q = 0.01 are shown in Figure 7A.

Figure 7. Single-layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin map, thickness and curvature.

A. Correlation map of single layer cortical T1w/T2w estimated myelination and cortical thickness at each vertex while controlling for cortical curvature. B. Correlation map of single layer T1w/T2w ratio and cortical curvature at each vertex while controlling for cortical thickness. Age, gender, handedness, scanner, console version and ICV were regressed out in calculating both maps. Only correlation coefficients surviving FDR with q = 0.01 are shown. While both positive and negative correlations are seen between T1w/T2w myelin and cortical thickness, the correlation between myelination and curvature is mostly negative.

A similar correlation analysis between cortical T1w/T2w myelination and curvature, while controlling for cortical thickness, resulted in mostly negative correlations throughout the cortex as can be seen in Figure 7B. Exceptions were small regions in the posterior cingulate, medial prefrontal, parahippocampal and temporal pole areas.

The two-layer T1w/T2w myelin maps were analyzed for thickness and curvature dependence in a similar manner. The relationship between inner and outer layer T1w/T2w myelination with cortical thickness was almost opposite (Figures. 8A and 8B). We found that the inner layer T1w/T2w value correlated positively with cortical thickness almost everywhere in the cortex (Figure 8A) with exceptions in some regions of the motor, somatosensory, visual, and cingulate cortices where the correlation was negative or insignificant. The outer layer T1w/T2w value correlated negatively (Figure 8B) with thickness in most cortical areas and showed positive or insignificant correlations in the visual cortex, auditory cortex, central sulcus, cingulate cortex and parahippocampal cortex. The positive correlation between outer layer T1w/T2w myelin and thickness was particularly strong in the visual cortex.

Figure 8. Two-layer cortical T1w/T2w estimated myelin map, thickness and curvature.

Panels A and B show the correlation of cortical thickness with the inner and the outer layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin maps, respectively, while controlling for curvature at each vertex. Panels C and D display correlation maps of cortical curvature with inner and outer layer T1w/T2w myelination, respectively, while controlling for cortical thickness at each vertex. Age, gender, handedness, scanner, console and ICV were regressed out in these correlation analyses. Only regions surviving FDR = 0.01 are shown. The medial wall is shown masked in gray.

The correlations between inner and outer layer T1w/T2w myelination and cortical curvature are shown in Figures 8C and 8D. Similar to the negative correlation between single-layer myelination and cortical curvature seen in Figure 7B, the inner and outer layer T1w/T2w maps also correlated mostly negatively with curvature. However, some regional differences were present: for example, the correlation between T1w/T2w myelin and curvature in the superior parietal region was stronger in the outer layer compared to the inner layer.

Together these results suggest that T1w/T2w estimated myelination, thickness and curvature influence each other but that the relationships between these quantities are not constant across the cortex.

3.5 T1w/T2w Myelin Increases with Age

The effect of age on the mean T1w/T2w estimated myelination of the cortex was explored. After regressing out the effects of sex, handedness, ICV, scanner, console version, mean thickness and mean curvature, a linear model was used to fit the residual T1w/T2w value to age, as shown in Figure 9A. The slope of the line was significant (p = 10−33) and positive, indicating that mean cortical T1w/T2w myelination increased with age between 18 and 35 years. Fitting the residuals to a quadratic model of age did not show improvement over the linear model (linear model R2 = 0.0954, quadratic model R2= 0.0947). To check replicability of our results once again we explored the effect of age on GRP1 and GRP2 separately. This analysis was limited to 18 – 28 year old subjects due to the relatively fewer number of subjects in the higher age range. A multiple linear regression model was fitted at each vertex with single layer T1w/T2w value as the dependent variable and age, sex, handedness, scanner, console version, thickness and curvature as independent variables. The partial regression coefficient of age, expressed as the percentage of mean T1w/T2w value at age 18 is shown in Figure 9B. The results for the two groups were found to be similar. Statistically significant (FDR, q = 0.05) positive age-dependence was seen almost everywhere on the cortex. The maximum rate of increase per year was found to be around 1% of the T1w/T2w myelination at age 18 (primary motor and somatosensory cortex). For single layer myelination, statistically significant age dependence was absent in small regions of the insular, superior parietal and primary visual cortices. Since the primary visual cortex and the insula are regions where segmentation and surface reconstruction are often difficult, it is possible that such technical issues might have contributed to the observed lack of age-dependence of the measured T1w/T2w myelin in these areas.

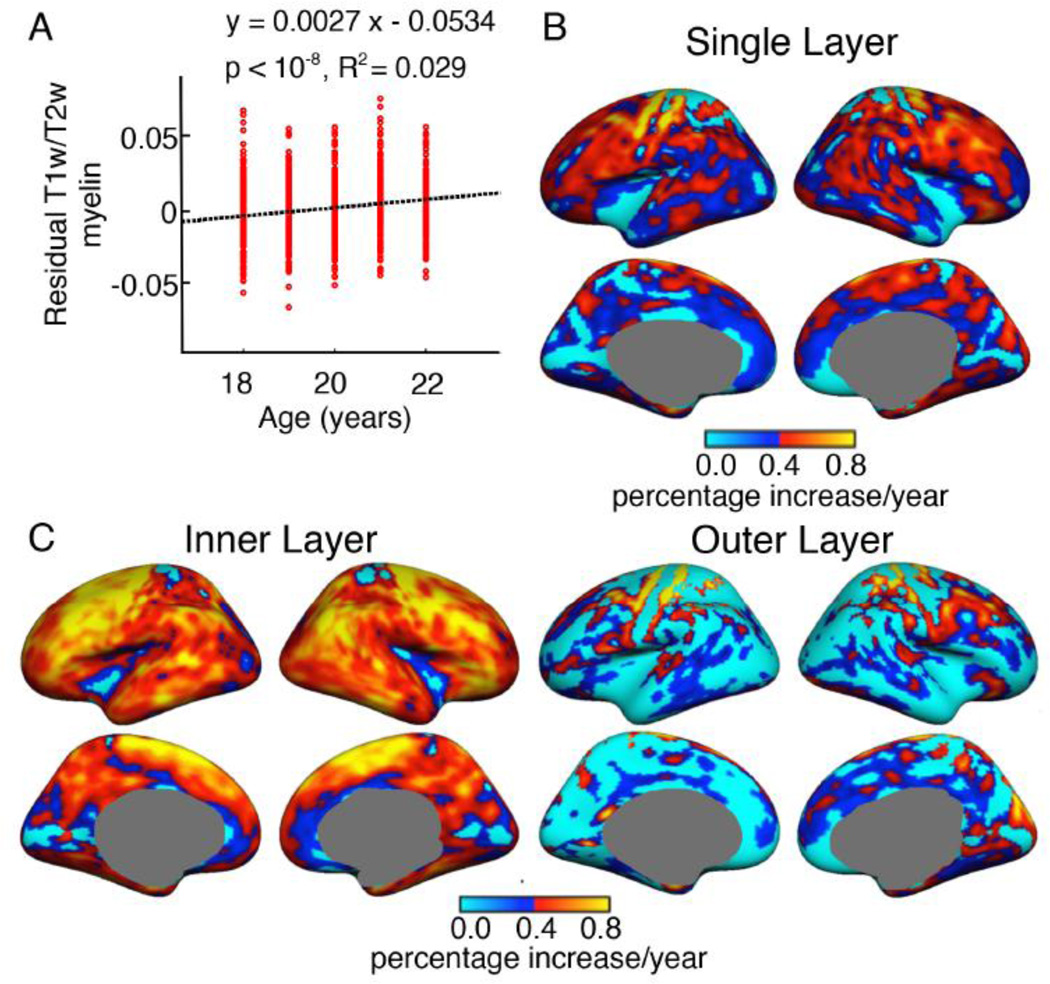

Figure 9. T1w/T2w estimated myelin increases with age.

A: residual mean single-layer T1w/T2w estimated myelination (after regression of sex, handedness, scanner, console, thickness and curvature) plotted against age. The significant linear fit indicates that mean T1w/T2w myelination increases with age in our cross-sectional sample. B. All-cortex map of the rate of change of T1w/T2w myelin with age shown for GRP1 and GRP2 separately. Almost global increase of T1w/T2w with age was detected in both groups with small regions in the insular, parietal, visual and cingulate cortices showing insignificant age dependence. To calculate the rate of change of T1w/T2w, a multiple regression model was fitted at each vertex with T1w/T2w as the independent variable and age, sex, handedness, scanner, console, ICV, thickness and curvature as dependent variables. The displayed rate of change is the regression coefficient of age normalized by the mean T1w/T2w value at that vertex at age 18. Only regression coefficients that survived FDR (q = 0.05) are shown in these maps. Insignificant age-dependence is shown in light blue.

To further quantify the estimated increase of myelination with age, a similar analysis was performed for the two-layer T1w/T2w myelin maps. The results are shown in Figure 10. The inner layer T1w/T2w myelination showed significant increase with age almost all over the cortex (Figure 10A). On the other hand, the T1w/T2w myelination of the outer layer of most cortical areas showed insignificant or weak age dependence compared to the inner layer (Figure 10B). Exceptions were noticed in the primary motor and somatosensory cortices, which displayed significant increase in T1w/T2w myelination in the outer layer as well as in the inner layer.

Figure 10. Age dependence of the two-layer T1w/T2w estimated myelin map.

Panels A and B display the rate of change of T1w/T2w estimated myelination with age (as described in Figure 9) in the inner layer and the outer layer, respectively. Results are shown for 18 – 28 year old subjects of GRP1 and GRP2. While statistically significant increase occurs in the inner layer of almost the entire cortex, the outer cortical layer shows little or no age dependence. Exceptions are noticed in the motor and somatosensory cortices, where the outer layer displays significant increase in T1w/T2w myelin with age.

To check for cohort effects arising from recruitment of subjects with different occupations (college students vs. non-college students, in particular) we repeated the analysis for the 18 to 22 year old subjects only (N = 1200). The pattern of rate of change of T1w/T2w myelin with age in this age group (Figure 11) overlapped significantly with that of the 18 – 35 year olds (Figure 9 and Figure 10) indicating that the observed increase of T1w/T2w myelin with age is possibly not driven by the occupational heterogeneity of the older subjects. However, some regions displaying significant age-dependence in the 18 – 35 year age range did not show statistical significance in the 18 – 22 year old age range (for example, medial prefrontal cortex in Figs. 9B and 11B). This was possibly due to the smaller number of subjects in the latter group. We further checked for cohort effects within the 18 – 22 year old group by investigating the relationship between age and both verbal and non-verbal IQ and found the results to be consistent with the absence of any cohort effect.

Figure 11. Age dependence of T1w/T2w estimated myelin in 18 to 22 year olds.

The effect of age on T1w/T2w estimated myelin was analyzed for only the 18 to 22 year old subjects (N = 1200) to check whether cohort effects were responsible for the age dependence seen in the 18 to 35 year old subjects. The effect of age is shown for A: mean single-layer T1w/T2w myelination, B: all-cortex T1w/T2w single-layer myelination, C: the inner layer of the two-layer T1w/T2w myelin map and D: the outer layer of the two-layer T1w/T2w myelin map. The units and calculations are same as those shown in Figures 9 and 10. Results for this subset of subjects are very similar to those shown in Figures 9 and 10 implying that it is unlikely that cohort effects are responsible for the observed age-related increase of T1w/T2w myelination.

3.6 Technical Concerns

Several technical issues in interpreting these results are noted and addressed below.

Since the individual z-score T1w/T2w myelin maps were calculated by combining both hemispheres (Figure 2) a direct comparison of the T1w/T2w maps of the left and the right hemisphere was possible. We noticed significant left-right asymmetry in both the PVC and the no-PVC maps particularly in the lateral occipital and temporal cortices. To check whether the asymmetry might be due to technical artifacts, we investigated the left-right asymmetry of the scanner bias field and concluded that the pattern of asymmetry of the T1w/T2w myelin map showed resemblance to the pattern of asymmetry of the scanner bias field, suggesting incomplete removal of bias field inhomogeneity by the T1w/T2w ratio technique. Similar T1w/T2w myelin maps presented by Glasser and Van Essen (2011) and Glasser et al. (2013) were normalized for each hemisphere separately. Hence it is not possible to compare our detected asymmetry with their results. Our results indicate that further work to improve removal of scanner-specific technical artifacts would be useful. The differences between the hemispheres that resemble features of the bias field is also a reminder that acquisition inhomogenity, even after best practice corrections, can still impact estimates of myelin.

A technical concern in interpreting the correlation between cortical thickness and estimated T1w/T2w myelin, particularly in the thinnest cortical regions such as the visual cortex, arises from how FreeSurfer relies on the image intensity as well as intensity gradient to generate the GM/WM surface. It is possible that in thinner cortical regions the GM/WM surface is mistakenly placed more superficially, making the cortex appear thinner and at the same time causing the T1w/T2w myelin value to be less. This effect could cause an artifactual positive correlation between thickness and T1w/T2w ratio (Glasser and Van Essen, 2011; Glasser et al., 2013). Due to the small number of high-resolution scans available to us we were unable to compare the results from the main dataset to data with smaller voxel size to quantify any such artifactual effect.

Several confounding factors could potentially influence the measurement of the real effect of age on cortical myelination in MRI. A subject’s movement in the scanner could affect image quality and indirectly affect the positioning and thickness estimation of the cortical surface. As a result, the T1w/T2w value could be erroneously detected to be a function of age if movement itself is age-dependent. However, the reproducibility of the result of the 18 – 35 year olds in the 18 – 22 year old subset (4 year age range) in our main cohort indicates that movement likely did not play a significant role in the detected increase of T1w/T2w myelin with age. Another possible confounding factor is the maturation of the local white matter (e.g., Giedd 2004) affecting the detected increase in T1w/T2w cortical myelin with age. In addition, given that the data are cross-sectional, there is also the possibility that our sample, which represents a convenience recruitment sample, differs as a function of age in ways that reflect imperfect cross-sectional matching. Further work with longitudinal data, higher resolution data, and postmortem data could help clarify these possible confounding effects.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1 MRI, Myelin and Comparison between Subjects

The above interpretations of our results rely on two assumptions: 1. The ratio of T1w and T2w image intensities is a reasonable measure of cortical myelin, and 2. This measure of myelination is comparable across subjects.

The first assumption is motivated by the observation that myelin is a significant source of image contrast in MRI. Since Clark et al. (1992) first used MRI to detect the Stria of Gennari in the primary visual cortex, many researchers have used T1 and T2 properties of brain tissue to detect highly myelinated regions of the cortex. Our work was motivated by the technique of Glasser & Van Essen (2011) who used the ratio of T1w and T2w images to successfully map the myeloarchitectonic properties of many cortical regions. However, it is known that iron, in addition to myelin, affects MR image intensities. For example, using a cohort of 4.5 to 71.9 year old subjects, Ogg and Steen (1998) showed that age-related changes in T1 relaxation rate vary linearly with brain iron concentration in the cortex even within the age range used in our work. However, iron and myelin are often co-localized in the cortex (Fukunaga et al., 2010). In a recent study Stüber et al. (2014) used ion beam analysis to evaluate the contributions of iron and myelin as sources of MR tissue contrast. Their results showed correspondence of iron, myelin and MR contrast in different MRI sequences with considerable overlap of iron and myelin distributions in the visual cortex and in motor/somatosensory cortex, in particular. Thus, while we expect factors in addition to myelin to affect the T1w/T2w image ratio, we interpret our results under the assumption that a large portion of the spatial variation of the T1w/T2w image ratio reflects variation of myelin density.

The second assumption was that the individual myelin maps are comparable across subjects. While factors including the non-uniformity of the field and the specific placement of each participant’s head within the field of view contribute to confounding differences between subjects, we took a number of steps to ensure consistency. All T1w and T2w scans were acquired on matched Siemens 3T Tim Trio scanners at Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital. In addition, the T1w and T2w images were bandwidth-matched and acquired during the same session, allowing accurate registration of the images at the single-voxel scale across the vast majority of the brain. These features make the dataset particularly suitable for implementing the image ratio technique used in this work, although acquisition differences across subjects and the inherent bias field certainly lead to unaccounted for sources of variation.

4.2 Laminar Distribution of Intracortical Myelin

Due to the spatial resolution of the data we divided the cortex into two equal thickness layers instead of the conventional six cortical layers. According to classic histological studies (Nieuwenhuys 2013, and references therein) cortical regions can be classified as bistriate, unistriate, unitostriate and astriate depending on the visibility of the myelinated fiber bands. Direct comparison of the cortical regions that showed the highest and the lowest inner to outer layer ratio of T1w/T2w myelin with the same regions of a high resolution ex-vivo MRI scan revealed that our technique was able to detect many expected differences in inner and outer layer tissue intensity change. Studies using alternate MRI techniques (Barazany and Assaf, 2011; Sereno et al., 2013) have also reported detectable changes in MR image intensity from the inner to the outer cortical layers.

Our technique can be applied to higher resolution data for more detailed investigation of the laminar properties of cortical myelination. Additionally, our method of PVC can be used together with alternate lamination techniques such as the equivolume model of Waehnert et al. (2013) to separate method-specific artifacts from biological effects.

4.3 Cortical Myelination and Age

Different anatomical and functional features of the brain follow different temporal trajectories as the brain reaches maturation. Similarly, age-related atrophy and myelination differences affect some brain regions more than others. The T1w/T2w myelin measure of the cortex increased significantly with age between 18 and 35 years in our cross-sectional cohort. In fact, the increase was significant even within only the 18 to 22 year old subjects (Figure 11). While our sample represents a cross-sectional convenience sample, it is intriguing that age related effects were present across such a constrained post-adolescent developmental range.

Prior work suggests myelination continues to change throughout the human lifetime. Classic histological studies reported that the course of maturation of different cortical regions vary significantly (Flechsig, 1901; Yakovlev & Lecours, 1967; Benes 1989; Benes et al, 1994). In their recent work Miller et al. (2012) used stereology in postmortem brain sections to quantify myelinated axon fiber length density throughout postnatal life in the human somatosensory, motor, frontopolar and visual cortices. Their results indicated that myelination in these regions continued to increase until the third decade of life, which is consistent with our findings. In another recent study, Grydeland et al. (2013) investigated the change in T1w/T2w myelin over the human life span using 8 to 83 year old subjects. Their results showed that intracortical T1w/T2w myelin increased linearly until the late 30s, followed by about 20 stable years before declining from the late 50s. They presented a map of the linear effect of age in the younger cohort (8 – 19 year olds) and quadratic age effect maps for the entire cohort (8 – 83 year olds) and the adult cohort (20 −83 year olds). In our 18 to 35 year old subjects an almost global statistically significant linear increase of T1w/T2w myelin with age was detected with no detectable quadratic age effect. The regions displaying the strongest age-dependence in our study overlap with regions of significant linear age effect of Grydeland et al.’s (2013) young cohort. The agreement between these two studies indicates that it is unlikely that technical issues such as scanner or location-specific biases contribute significantly to the findings. Additionally, Miller et al (2012), who also reported increasing myelinated fiber length density well into the 30s, used a non-MRI technique of stereology in postmortem brains to draw their conclusions. Together these results suggest the potential of using MRI T1w/T2w image intensity as a proxy for cortical myelin density in the living human brain.

Studies have shown that the myelin content of subcortical structures also changes throughout the human lifetime. Kochunov et al. (2011) showed that mean cortical thickness and brain WM fractional anisotropy (FA) both follow a quadratic aging trajectory and noted a linear relationship between these two quantities. They concluded that the age-related changes in GM thickness and FA are at least partially driven by a common biological mechanism, presumed to be related to changes in cerebral myelination. In a recent MRI study Callaghan et al. (2014) showed that effective transverse relaxation rate R2* and magnetization transfer (MT) measures change throughout the lifetime implying increase in the iron content and decrease of myelination in both the cortex and subcortical structures. Their study included 19 to 75 year old subjects and as the authors pointed out, due to fewer subjects in the 35 to 55 year range the study was more sensitive to linear effects of age instead of the quadratic effect of age reported by other studies. Possibly due to this reason they did not detect increase in cortical myelination in the 18 to 35 year age range.

4.4 Conclusions, Limitations and Future Work

In this work a new partial volume correction algorithm was used to quantify a T1w/T2w estimate of cortical myelination in 1555 healthy young adults. We found significant agreement between our results and past histological results as well as findings from other recent in vivo investigations of cortical myelination. However, we also find that without partial volume correction the T1w/T2w intensity ratio of cortical GM is overestimated. Additionally, results revealed that cortical thickness, curvature and the estimated T1w/T2w myelin value are interdependent and that the magnitude of partial volume correction itself varies across the cortex. Together these results suggest that our technique might provide a more accurate estimation of an individual’s T1w/T2w cortical myelination map than methods that do not incorporate this correction. Also consistent with past ex vivo results, the inner cortical layers were found to be more heavily myelinated than the outer layers in most cortical regions. Exceptions were noticed in a few cortical regions, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, where the T1w/T2w myelin ratio of the inner layers appeared to be comparable to that of the outer layers. Further investigation of these regions in a high-resolution postmortem brain and also in high-resolution in vivo scans provided results that were consistent with the results of the main dataset making it unlikely that the observed T1w/T2w myelin ratio in these cortical areas was due to technical artifacts. Additionally, we detected that the ratio of T1w/T2w myelin increased with age between 18 and 35 years in our cross-sectional sample and that this increase occurred mostly in the inner cortical layers.

Although MRI is a useful tool for investigating anatomical features of the brain, confounders such as scanner bias field or slight differences in scanning protocol can affect measurements such as GM thickness and the volumes of different structures. Such confounds can affect regional T1w and T2w image intensities as well. We attempted to minimize such effects by using the same scanning protocol for all subjects and also by using bandwidth-matched T1w and T2w images. However, the present method can be improved by implementing solutions to issues such as biases in the positioning of the cortical surfaces and the influence of blood vessels on measured GM intensity, as investigated by Glasser et al. (2013). Replication of the relationship between thickness, curvature and T1/T2w myelin using a higher resolution dataset and further investigation of the effect of age in a longitudinal cohort will clarify the contributions of such confounding factors.

In this work we were able to noninvasively detect the age-related differences in cortical T1w/T2w ratio myelin density across a limited age range of 18 to 35 years, which includes the age of onset for neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. These disorders have been found to exhibit differences in white matter volume and integrity (Davis et al., 2003; Höistad et al., 2009; Kubicki & Shenton, 2014; Sarrazin et al, 2014) and reduced myelin-related gene expression (Dracheva et al., 2006; Hakak et al., 2001; McCullumsmith et al., 2007; Harris et al., 2009). An important next step would be to apply our technique to explore the possibly disrupted developmental trajectory of cortical myelination in diseased cohorts. The option to create multiple layers within the cortex and the ability to apply partial volume correction at each laminar boundary makes this algorithm particularly suitable for the exploration of detailed lamination patterns of cortical myelination in higher resolution data, and for laminar analysis of other imaging modalities such as high-resolution functional MRI (Polimeni et al., 2010).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Without partial volume correction T1w/T2w myelination may be overestimated.

Average myelin maps presented for 1555 clinically normal 18 – 35 year old subjects.

Inner cortical layers show higher T1w/T2w myelination compared to outer layers.

T1w/T2w myelination of the cortex increases with age between 18 and 35 years.

Age-dependent increase of myelination occurs mostly in the inner cortical layers.

Acknowledgements

Data were provided [in part] by the Brain Genomics Superstruct Project of Harvard University and the Massachusetts General Hospital, (Principal Investigators: Randy Buckner, Joshua Roffman, and Jordan Smoller), with support from the Center for Brain Science Neuroinformatics Research Group, the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, and the Center for Human Genetic Research. 20 individual investigators at Harvard and MGH generously contributed data to the overall project. Support for this research was provided by HHMI, National Center for Research Resources (U24 RR021382), the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (5P41EB015896-15, R01EB006758), the National Institute on Aging (AG022381, 5R01AG008122-22, R01 AG016495-11), the National Center for Alternative Medicine (RC1 AT005728-01), the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS052585-01, 1R21NS072652-01, 1R01NS070963), and was made possible by the resources provided by Shared Instrumentation Grants 1S10RR023401, 1S10RR019307, and 1S10RR023043. Additional support was provided by The Autism & Dyslexia Project funded by the Ellison Medical Foundation, and by the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (5U01-MH093765), part of the multi-institutional Human Connectome Project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdollahi RO, Kolster H, Glasser MF, Robinson EC, Coalson TS, Dierker D, Jenkinson M, Van Essen DC, Guy OA. Correspondences between retinotopic areas and myelin maps in human visual cortex. Neuroimage. 2014;99:509–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annese J, Pitiot A, Dinov ID, Toga AW. A myelo-architectonic method for the structural classification of cortical areas. Neuroimage. 2004;21:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barazany D, Assaf Y. Visualization of cortical lamination patterns with magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb. Cortex. 2012;22:2016–2023. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier EL, Marrett S, Danek A, Vortmeyer A, van Gelderen P, Duyn J, Bandettini P, Grafman J, Koretsky AP. Imaging cortical anatomy by high-resolution MR at 3.0T: detection of the stripe of Gennari in visual area 17. Magn. Reson. Med. 2002;48:735–738. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM. Myelination of cortical-hippocampal relays during late adolescence. Schizophr. Bull. 1989;15:585–593. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM, Turtle M, Khan Y, Farol P. Myelination of a key relay zone in the hippocampal formation occurs in the human brain during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Arch. Gen. Psych. 1994;51:477–484. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950060041004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock NA, Kocharyan A, Liu JV, Silva AC. Visualizing the entire cortical myelination pattern in marmosets with magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009;185:5–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock NA, Hashim E, Kocharyan A, Silva AC. Visualizing myeloarchitecture with magnetic resonance imaging in primates. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1225(Suppl):E171–E181. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock NA, Hashim E, Janik R, Konyer NB, Weiss M, Stanisz GJ, Turner R, Geyer S. Optimizing T1-weighted imaging of cortical myelin content at 3.0 T. Neuroimage. 2013;65:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge H, Clare S, Jenkinson M, Jezzard P, Parker AJ, Matthews PM. Independent anatomical and functional measures of the V1 / V2 boundary in human visual cortex. J. Vis. 2005;5:93–102. doi: 10.1167/5.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Head D, Parker J, Fotenos AF, Marcus D, Morris JC, Snyder AZ. A unified approach for morphometric and functional data analysis in young, old, and demented adults using automated atlas-based head size normalization: reliability and validation against manual measurement of total intracranial volume. Neuroimage. 2004;23:724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan MF, Freund P, Draganski B, Anderson E, Cappelletti M, Chowdhury R, Diedrichsen J, Fitzgerald TH, Smittenaar P, Helms G, Lutti A, Weiskopf N. Widespread age-related differences in the human brain microstructure revealed by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:1862–1872. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare S, Bridge H. Methodological issues relating to in vivo cortical myelography using MRI. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005;26:240–250. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark VP, Courchesne E, Grafe M. In vivo myeloarchitectonic analysis of human striate and extrastriate cortex using magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb. Cortex. 1992;2:417–424. doi: 10.1093/cercor/2.5.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Adad J, Polimeni JR, Helmer KG, Benner T, McNab JA, Wald LL, Rosen BR, Mainero C. T2* mapping and Bo orientation-dependence at 7 T reveal cyto-and myeloarchitecture organization of the human cortex. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, Stewart DG, Friedman JI, Buchsbaum M, Harvey PD, Hof PR, Buxbaum J, Haroutunian V. White matter changes in schizophrenia: Evidence for myelin related dysfunction. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:443–456. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick F, Tierney AT, Lutti A, Josephs O, Sereno MI, Weiskopf N. In vivo functional and myeloarchitectonic mapping of human primary auditory areas. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16095–16105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dracheva S, Davis KL, Chin B, Woo DA, Schmeidler J, Haroutunian V. Myelin-associated mRNA and protein expression deficits in the anterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus in elderly schizophrenia patients. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;21:531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk KR, Sabuncu MR, Buckner RL. The influence of head motion on intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage. 2012;59:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff S, Walters NB, Schleicher A, Kril J, Egan GF, Zilles K, Watson JD, Amunts K. High-resolution MRI reflects myeloarchitecture and cytoarchitecture of human cerebral cortex. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005;24:206–215. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999a;9:195–207. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RB, Dale AM. High-resolution intersubject averaging and a coordinate system for the cortical surface. Hum. Brain Mapp. 1999b;8:272–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<272::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:11050–11055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, van der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, van der Kouwe AJ, Makris N, Ségonne F, Quinn BT, Dale AM. Sequence-independent segmentation of magnetic resonance images. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S69–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flechsig P. Developmental (myelogenetic) localization of the cerebral cortex in the human. Lancet. 1901;158:1027–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga M, Li TQ, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Shmueli K, Yao B, Lee J, Maric D, Aronova MA, Zhang G, Leapman RD, Schenck JF, Merkle H, Duyn JH. Layer-specific variation of iron content in cerebral cortex as a source of MRI contrast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:3834–3839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911177107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Weiss M, Reimann K, Lohmann G, Turner R. Microstructural parcellation of the human cerebral cortex - from Brodmann's post-mortem map to in vivo mapping with high-field magnetic resonance imaging. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011;5:19. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN. Structural magnetic resonance imaging of the adolescent brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1021:77–85. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, Van Essen DC. Mapping human cortical areas in vivo based on myelin content as revealed by T1- and T2-weighted MRI. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:11597–11616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2180-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, Goyal MS, Preuss TM, Raichle ME, Van Essen DC. Trends and properties of human cerebral cortex: correlations with cortical myelin content. Neuroimage. 2013;93P2:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve DN, Fischl B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage. 2009;48:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grydeland H, Walhovd KB, Tamnes CK, Westlye LT, Fjell AM. Intracortical myelin links with performance variability across the human lifespan: results from T1- and T2-weighted MRI myelin mapping and diffusion tensor imaging. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:18618–18630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2811-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, Wong WH, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD, Haroutunian V, Fienberg AA. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:4746–4751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081071198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LW, Lockstone HE, Khaitovich P, Weickert CS, Webster MJ, Bahn S. Gene expression in the prefrontal cortex during adolescence: implications for the onset of schizophrenia. BMC medical genomics. 2009;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höistad M, Segal D, Takahashi N, Sakurai T, Buxbaum JD, Hof PR. Linking white and grey matter in schizophrenia: Oligodendrocyte and neuron pathology in the prefrontal cortex. Front. Neuroanat. 2009;3:9. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.009.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes AJ, Lee PH, Hollinshead MO, Bakst L, Roffman JL, Smoller JW, Buckner RL. Individual differences in amygdala-medial prefrontal anatomy link negative affect, impaired social functioning, and polygenic depression risk. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:18087–18100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2531-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov P, Glahn DC, Lancaster J, Thompson PM, Kochunov V, Rogers B, Fox P, Blangero J, Williamson DE. Fractional anisotropy of cerebral white matter and thickness of cortical gray matter across the lifespan. Neuroimage. 2011;58:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki M, Shenton ME. Diffusion tensor imaging findings and their implications in schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2014;27:179–184. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kouwe AJ, Benner T, Salat DH, Fischl B. Brain morphometry with multiecho MPRAGE. Neuroimage. 2008;40:559–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichy MP, Wietek BM, Mugler JP3rd, Horger W, Menzel MI, Anastasiadis A, Siegmann K, Niemeyer T, Köigsrainer A, Kiefer B, Schick F, Claussen CD, Schlemmer HP. Magnetic resonance imaging of the body trunk using a single-slab, 3-dimensional, T2-weighted turbo-spin-echo sequence with high sampling efficiency (SPACE) for high spatial resolution imaging: initial clinical experiences. Invest. Radiol. 2005;40:754–760. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000185880.92346.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutti A, Dick F, Sereno MI, Weiskopf N. Using high-resolution quantitative mapping of R1 as an index of cortical myelination. Neuroimage. 2013;93P2:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullumsmith RE, Gupta D, Beneyto M, Kreger E, Haroutunian V, Davis KL, Meador-Woodruff JH. Expression of transcripts for myelin-related genes in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Schizoprh. Res. 2007;90:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DJ, Duka T, Stimpson CD, Schapiro SJ, Baze WB, McArthur MJ, Fobbs AJ, Sousa AM, Sestan N, Wildman DE, Lipovich L, Kuzawa CW, Hof PR, Sherwood CC. Prolonged myelination in human neocortical evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:16480–16485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117943109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R. The myeloarchitectonic studies on the human cerebral cortex of the Vogt-Vogt school, and their significance for the interpretation of functional neuroimaging data. Brain Struct. Funct. 2013;218:303–352. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0460-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg RJ, Steen RG. Age-related changes in brain T1 are correlated with iron concentration. Magn. Reson. Med. 1998;40:749–753. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni JR, Fischl B, Greve DN, Wald LL. Laminar analysis of 7T BOLD using an imposed spatial activation pattern in human V1. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1334–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin S, Poupon C, Linke J, Wessa M, Phillips M, Delavest M, Versace A, Almeida J, Guevara P, Duclap D, Duchesnay E, Mangin JF, Le Dudal K, Daban C, Hamdani N, D’Albis MA, Leboyer M, Houenou J. A multicenter tractography study of deep white matter tracts in bipolar I disorder: psychotic features and interhemispheric disconnectivity. J.A.M.A. Psychiatry. 2014;71:388–396. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ségonne F, Dale AM, Busa E, Glessner M, Salat D, Hahn HK, Fischl B. A hybrid approach to the skull stripping problem in MRI. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1060–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno MI, Lutti A, Weiskopf N, Dick F. Mapping the human cortical surface by combining quantitative T1 with retinotopy. Cereb. Cortex. 2013;23:2261–2268. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigalovsky IS, Fischl B, Melcher JR. Mapping an intrinsic MR property of gray matter in auditory cortex of living humans: a possible marker for primary cortex and hemispheric differences. Neuroimage. 2006;32:1524–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stüber C, Morawski M, Schafer A, Labadie C, Wahnert M, Leuze C, Streicher M, Barapatre N, Reimann K, Geyer S, Spemann D, Turner R. Myelin and iron concentration in the human brain: A quantitative study of MRI contrast. Neuroimage. 2014;93:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waehnert MD, Dinse J, Weiss M, Streicher MN, Waehnert P, Geyer S, Turner R, Bazin PL. Anatomically motivated modeling of cortical laminae. Neuroimage. 2013;93P2:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters NB, Egan GF, Kril JJ, Kean M, Waley P, Jenkinson M, Watson JD. In vivo identification of human cortical areas using high-resolution MRI: an approach to cerebral structure-function correlation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:2981–2986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437896100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters NB, Eickhoff SB, Schleicher A, Zilles K, Amunts K, Egan GF, Watson JD. Observer-independent analysis of high-resolution MR images of the human cerebral cortex: in vivo delineation of cortical areas. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007;28:1–8. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev PI, Lecours AR. The myelogenetic cycles of regional maturation of the brain. In: Minkowski A, editor. regional development of the brain in Early Life. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1967. pp. 3–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo BT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, Roffman JL, Smoller JW, Zöllei L, Polimeni JR, Fischl B, Liu H, Buckner RL. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–1165. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data