Abstract

The present study examines the influences of mothers’ emotional availability towards their infants during bedtime, infant attachment security, and interactions between bedtime parenting and attachment with infant temperamental negative affectivity, on infants’ emotion regulation strategy use at 12 and 18 months. Infants’ emotion regulation strategies were assessed during a frustration task that required infants to regulate their emotions in the absence of parental support. Whereas emotional availability was not directly related to infants’ emotion regulation strategies, infant attachment security had direct relations with infants’ orienting towards the environment and tension reduction behaviors. Both maternal emotional availability and security of the mother-infant attachment relationship interacted with infant temperamental negative affectivity to predict two strategies that were less adaptive in regulating frustration.

Keywords: Maternal Emotional Availability, Attachment Security, Infant Temperament, Emotion Regulation

1. Introduction

The ability to regulate emotions and related behaviors in socially adaptive ways is an essential aspect of children’s successful development (Calkins & Leerkes, 2010; Halberstadt, Denham, & Dunsmore, 2001; Kopp, 1989; Thompson, 1994). Lack of emotion regulation skills during infancy and toddlerhood is not only indicative of later aggressive or withdrawn behaviors (Calkins, Smith, Gill, & Johnson, 1998) but also predictive of problems in cognitive and social development through the preschool and early school years (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers & Robinson, 2007).

Both theory and empirical studies indicate that the parent-infant relationship exerts significant influence on infants’ regulatory capacities (Cassidy, 1994; Kogan & Carter, 1996; Sroufe, 1995, 2005). The quality of parent-child interactions has been particularly emphasized as an influence on children’s developing emotion regulation (Spinrad & Stifter, 2002; Sroufe, 1995). It is during healthy interactions with parents that a child acquires knowledge of emotions and adaptive regulatory strategies (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBridge-Chang, 2003; Parke, Cassidy, Burks, Carson, & Boyum, 1992). Indeed, the ways in which mothers respond to their children’s emotional cues are related to children’s emotional competence (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Morris et al., 2007). Despite the wealth of studies examining relations between the quality of parenting and child regulatory outcomes, most studies relate individual dimensions of parenting (e.g., sensitivity) in relation to various aspects of emotional competence in infants, toddlers, and preschoolers (e.g., emotion understanding, intensity and duration of emotional expression, and emotion regulation strategies). We thus employ, in the present study, the multidimensional construct of emotional availability that involves affective attunement to the child’s emotions, needs, and goals, an acceptance of both positive and negative emotions in the child, and adaptive regulation of emotional exchanges during interactions with the child (Biringen, 2000; Emde & Easterbrooks, 1985). Emotionally available parents engage in sensitive, structuring, nonintrusive, and non-hostile behaviors that enable the child to use the parent for comfort and support as well as engage in adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Biringen, 2000; Biringen, Robinson, & Emde, 1998; Kogan & Carter, 1996; Little & Carter, 2005).

The present study examines parental emotional availability during the context of bedtime as a predictor of child emotion regulation. Bedtime is a naturalistic, daily-occurring context for which parents have the goal of bringing the child to a comfortable, restful, and non-distressed affective state so that the child can fall asleep and sleep throughout the night, typically apart from parents. Cessation of parent-infant interactions and separation from parents during bedtime may potentially be distressing for children who wish to maintain contact or interaction with their parents (Sadeh, Tikotzky, & Scher, 2010). Emotionally available parents who respond contingently and appropriately to child signals, make effective use of bedtime routines to facilitate children’s sleep by avoiding intense or high-level stimulation of the child when the child is settling to sleep at bedtime, and refraining from overt and covert expressions of irritability or anger when interacting with the child. These routines are expected to promote a safe and secure affective state in their children, and to enable adaptive emotion regulatory capabilities during distressing situations.

Taken together, the findings of studies that have examined individual dimensions of parenting (i.e., sensitivity, structuring, intrusiveness, or hostility) in relation to infant emotional competence indicate that early caregiving plays an important role in the development of children’s emotion regulation (Kogan & Carter, 1996; Leerkes, Blankson, & O’Brien, 2009). Children with mothers that respond sensitively to their changing emotional cues tend to show lower negative reactivity and more regulatory strategies than children whose mothers are less sensitive (Spinrad & Stifter, 2002). Sensitive responsivity to children’s distress also seems to engender children’s use of more age-appropriate emotion regulation strategies that are less self-oriented (e.g., thumb sucking) and more parent-oriented (e.g., focuses gaze on parent; Eisenberg et al., 1998). Parents structure children’s self-regulation of emotion through encouraging the child to shift attention, and modeling the use of adaptive strategies in response to distress (Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon, & Cohen, 2009; Raikes & Thompson, 2006). Mothers who engage in emotionally available structuring pace their activity level in response to the child’s cues such as gaze aversion, scaffold self-soothing by providing security objects, and provide positive guidance that will help children learn to regulate their emotions in adaptive ways (Calkins et al., 1998; Leerkes et al., 2009). When parents react negatively (e.g., reject, punish, or ignore) to children’s distress, negative arousal is less likely to decrease, and maladaptive regulation in the form of minimization or over-regulation of emotions is likely to occur (Cassidy, 1994). Studies have shown that maternal intrusive and hostile behaviors (e.g., being constantly at the child, expressing irritation or anger, and scolding or teasing) that exert excessive or negative control over the child are linked with greater orienting towards sources of frustration and fewer adaptive emotion regulation strategies in the child (Calkins et al., 1998; Chang et al., 2003; Little & Carter, 2005).

Along with parenting quality, the mother-infant attachment relationship has both theoretical and empirical links to children’s emotion regulation. According to attachment theory, parent-initiated regulation of emotions during face-to-face interactions in the earliest months, help infants to gain the ability for dyadic coregulation in the first year (Cassidy, 1994; Sroufe, 1995). With repeated interactions with parents in emotion-laden contexts, infants become increasingly able to autonomously use strategies to regulate their emotional arousal (Calkins et al., 1998; Feldman, Greenbaum, & Yirmiya, 1999; Kopp 1989). The organization of behaviors within the attachment relationship thus affects how children organize and regulate their emotions and behaviors towards the environment (Ainsworth, 1979; Sroufe & Waters, 1977; Thompson, 2008).

Attachment theory posits securely attached children to show more adaptive emotion regulation than children with insecure attachment (Bridges & Grolnick, 1995; Cassidy, 1994; Sroufe, 2005). Children who have confidence in the parent’s capacity to provide assistance in regulating their affective states will be able to better regulate emotional arousal and also effectively explore their environment which, in turn, has positive implications for adjustment (Eisenberg et al., 2001; Sroufe, 1995, 2005). Indeed, secure attachment is associated with more adaptive emotion regulation (Diener, Mangelsdorf, McHale, & Frosch, 2002; Waters et al., 2010), including more parent-oriented and less object-orientated emotion regulation strategies during a frustration task (Braungart & Stifter, 1991; Diener et al., 2002; Leerkes & Wong, 2012).

On the other hand, children with insecure attachments show greater emotion dysregulation (Sroufe, 2005), placing them at greater risk for externalizing and internalizing problems, and psychopathology (Cassidy, 1999; Madigan, Moran, Schuengel, Pederson, & Otten, 2007). Insecure-avoidant infants who likely experienced repeated rejection from their parent tend to engage in less parent-oriented, more object-oriented, and more self-comforting emotion regulation strategies (Braungart & Stifter, 1991; Crugnola et al., 2011; Diener et al., 2002; Leerkes & Wong, 2012; Martins, Soares, Martins, Tereno, & Osório, 2012). Insecure-resistant infants are more likely to employ high levels of parent-oriented emotion regulation strategies possibly due to their uncertainty of parental emotional availability based on a history of inconsistent care (Bridges & Grolnick, 1995; Cassidy, 1994). They are also more likely to use tension-reduction strategies, such as hitting or throwing the object (e.g., toy) when distressed (Calkins & Johnson, 1998; Leerkes & Wong, 2012).

Both temperament and attachment perspectives on children’s emotional development agree that the emotion regulation abilities of infants are based on an interaction between the infant’s temperamental characteristics and environmental influences (Calkins & Leerkes, 2010; Sroufe, 1995; Thompson, 1994). Given the bidirectional nature of parent-infant interactions, the present study also examines whether infant temperamental reactivity moderates the relation between bedtime parenting quality/parent-infant relationship and infant emotion regulation. Children who are temperamentally reactive may be more sensitive to their environment, namely parenting quality and the attachment relationship, given their greater likelihood of becoming distressed in a frustrating situation, greater dependence on external sources of regulation, and higher risk for maladjustment (Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011; Stupica, Sherman, & Cassidy, 2011). As stipulated by the differential susceptibility hypothesis, reactive infants may be differentially susceptible to both positive and negative parenting quality, and to both secure and insecure attachment (Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2011). Studies have found parenting quality to more strongly predict social-emotional and behavioral outcomes for temperamentally reactive children than for less reactive children (Belsky, 2005; Belsky & Pluess, 2009; van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2012). Leerkes et al. (2009), for example, found that maternal sensitivity to child distress was associated with lower emotion dysregulation only for highly reactive 24-month olds. In addition, Ursache, Blair, Stifter, and Voegtline (2013) found that 15-month olds with both high emotional reactivity and high emotion regulation were the most likely to have caregivers who showed more supportive parenting.

The differential susceptibility hypothesis and empirical findings suggest that high maternal emotional availability marked by sensitivity to child cues, appropriate structuring, and non-intrusive and non-hostile responses during bedtime are more likely to influence the emotion regulation abilities of highly reactive infants than those of low reactive infants. High emotional availability may predict greater use of adaptive regulatory strategies, whereas low emotional availability may predict greater use of less-adaptive regulatory strategies for highly reactive, but not low reactive, infants. Similarly, infant temperament may interact with attachment security to predict emotion regulation strategies such that highly reactive infants, compared to low reactive infants, may use more adaptive strategies when securely attached, and to use more of the less-adaptive strategies when insecurely attached. It is plausible that the relations between particular emotion regulation strategies and insecure attachment (e.g., the greater use of tension reduction behaviors in resistant infants) as found in previous studies are stronger for highly reactive infants.

The Present Study

According to Thompson (1994), emotion regulation “consists of extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one’s goals” (pp. 27–28). Working with this definition, the present study’s goal is to examine whether the “extrinsic and intrinsic processes” involved in both maternal parenting quality and the mother-infant attachment relationship, and the “intrinsic processes” of infant temperamental negative affectivity, predict the behavioral emotion regulation strategies that infants employ to “modify emotional reactions” (i.e., frustration) in service of the “goals” of playing with an attractive toy (and mother). The regulatory strategies of orienting towards the environment, focusing on the mother and/or toy, self-comforting, avoidance, and tension reduction behaviors will be examined (Stifter & Braungart, 1995).

Whether an emotion regulation strategy is adaptive often depends on the goals of the infant in the current situation that the infant faces (Thompson, 1994). In the present study, infant emotion regulation will be assessed during a frustrating situation, a common occurrence for infants (Stifter & Braungart, 1995). When infants are denied access to an attractive toy as well as responses from the mother, they may experience frustration. Research has shown that certain regulatory behaviors are more adaptive than others in reducing frustration (Stifter & Braungart, 1995; Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Diener & Mangelsdorf, 1999; Ekas, Braungart-Rieker, Lickenbrock, Zentall, & Maxwell, 2011); thus, it may be most adaptive to orient towards the toy and the mother at first, but turn to other strategies, such as redirecting attention towards the environment, that will help reduce frustration when the mother continues to be unresponsive. In addition, strategies such as avoidance (e.g., pushing back on the high chair in which they are seated) or tension reduction behaviors (e.g., actively banging legs against the high chair) may be less adaptive in that they either maintain or increase infants’ frustration.

The study hypotheses are as follows. First, maternal bedtime emotional availability at 12 and 18 months was expected to predict infants’ use of emotion regulation strategies at 12 and 18 months, both concurrently and longitudinally. When emotional availability was high, infants were expected to engage in emotion regulation strategies that would be adaptive in a situation during which the infant is denied access to an attractive toy as well as responses from the mother: orient (redirect attention) towards the environment, focus less on both the source of frustration (the attractive toy) and the mother who is unavailable, and self-comforting. Conversely, infants were expected to engage in more of the less-adaptive strategies – avoidance and tension reduction behaviors – when emotional availability was low. Second, infant attachment security at 12 months was expected to predict infants’ use of emotion regulation strategies at 12 and 18 months. In line with attachment theory and previous findings, secure infants were expected to engage in more adaptive strategies than insecure infants; insecure-avoidant infants were expected to engage in less mother-oriented, more object (toy)-oriented, and more self-comforting strategies (Braungart & Stifter, 1991; Crugnola et al., 2011; Diener et al., 2002; Leerkes & Wong, 2012); and insecure-resistant infants were expected to engage in more mother-oriented, avoidance, and tension-reduction strategies (Crugnola et al., 2011; Leerkes & Wong, 2012), compared to secure infants. Third, infant temperamental negative affectivity (at 12 and 18 months) was expected to moderate the relation between maternal bedtime emotional availability and infant emotion regulation strategies at 12 and 18 months. In accordance with the differential susceptibility hypothesis, high maternal emotional availability was expected to predict greater use of adaptive strategies, and low emotional availability to predict greater use of less-adaptive strategies, for infants high on negative affectivity, compared to infants low on negative affectivity. Finally, infant temperamental negative affectivity (at 12 months) was expected to moderate the relation between attachment security and emotion regulation strategies at 12 and 18 months. As predicted by the differential susceptibility hypothesis, secure infants were expected to use more adaptive strategies compared to insecure infants, and insecure infants to use more less-adaptive strategies compared to secure infants, only among infants high on negative affectivity.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample of 144 mothers and their infants came from a larger NIH-funded two-year longitudinal study of parenting, infant sleep, and infant development (SIESTA – Study of Infants’ Emergent Sleep TrAjectories). A total of 167 mothers who were 18 years or older, of any ethnic background, and fluent in English were recruited from the obstetric floors of the Mt. Nittany Medical Center Mother and Baby Clinic and the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in central Pennsylvania, shortly after mothers had given birth. The 23 families who had dropped out of the study by 12 months or were missing data for all study variables were not included in the present study. No sociodemographic differences were found between these mothers not included in the study, and the mothers in the final study sample.

The final study sample included 78 (54.2%) female and 54 (37.5%) first-born infants. Mothers’ average age was 30.2 years (SD = 5.2), 84.7% of mothers were married, 34.0% graduated from college, and 30.6% obtained graduate or professional degrees. Two-thirds (66.0%) of mothers were employed, and the average family income was $71,575 (ranging from $5,000 to $350,000). The ethnic composition of the sample was: 86.1% White, 3.5% African American, 2.1% Asian, 4.9% Latino, and 2.8% Other.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Bedtime parenting quality (12 and 18 months)

Video recordings of infant bedtimes were obtained when infants were 12 and 18 months of age. A digital video recorder, night-vision cameras, and microphones were used to capture parent-infant bedtime interactions. Cameras were focused on areas in which parent-infant bedtime interactions took place: the infant’s typical sleep location (e.g., crib), a chair in the infant’s or parents’ room, and another room such as the living room or basement. Parents were instructed to start the video recording approximately one hour before they began to get their infant ready for bed. The average length of infant bedtimes was 45.89 minutes (SD = 30.10) at 12 months, and 49.95 minutes (SD = 37.41) at 18 months.

Video-recordings of bedtime parenting could not be obtained or coded for 40 families at 12 months, and 55 families at 18 months. Reasons included attrition, no consent for video-recording, unspecified negative life events, and lack of bedtime interaction (e.g., a bedtime routine that was too short to assess parenting quality, bedtime activities carried out in a room without a camera, and video recording turned on after the infant was already asleep).

The emotional quality of bedtime parenting was coded by the author and another coder using the Emotional Availability Scales (EAS; Biringen et al., 1998). Four dimensions of emotional availability that were adapted to the bedtime context (according to Teti, Kim, Mayer, & Countermine, 2010) were scored. Sensitivity assessed mothers’ accurate, appropriate, and prompt responses to their infants during bedtime activities. Structuring assessed mothers’ successful use of bedtime routines to guide infants toward sleep. Mothers were scored lower on sensitivity and structuring if they took longer than 1 minute to respond to their infants who became distressed after being put down to sleep. Non-intrusiveness assessed whether mothers initiated new interactions that interfered with the infant falling asleep, or overly insisted that the infant fall asleep. Non-hostility assessed mothers’ expression of covert (e.g., impatience) and/or overt (e.g., anger) hostility during interactions with their infants. The two child emotional availability scales (responsiveness and involvement) were not included in the present study because the focus was on the parents’ contribution to the quality of parent-infant interaction, and the behavioral repertoire of the infants during the bedtime context was limited and thus less readily scoreable.

Intra-class correlations (absolute agreement) for the four emotional availability dimensions ranged from .98 to 1.00 for 8 (7.7%) randomly-selected 12-month tapes, and 9 (10.1%) randomly-selected 18-month tapes. At each time point, z-scores for the four dimensions were computed and combined to create a composite emotional availability score in which higher scores indicate higher emotional availability (α = .82 at 12 months, α = .90 at 18 months).

2.2.2. Infant attachment security (12 months)

When infants were 12 months of age, infants and their mothers completed the Strange Situation procedure (Teti & Kim, in press), a measure of mother-infant attachment security. The procedure is comprised of eight 3-minute episodes. In Episode 1, the infant and mother are introduced to the room with developmentally-appropriate toys on the floor, and two chairs (one for the mother and another for the stranger who enters the room later). In Episode 2, the infant plays with the toys, and the mother takes a seat on one of the chairs. An adult stranger (female) enters the room in Episode 3. In Episode 4, the mother is cued to leave the room. The stranger comforts the infant if he/she becomes distressed. The mother returns to the room during Episode 5, and comforts the infant if distressed and re-engages the infant with the toys. The stranger leaves. In Episode 6, the mother leaves the room for the second time. This episode is cut short if the infant becomes highly distressed. The stranger re-enters the room in Episode 7, and comforts the infant if distressed. Finally, in Episode 8, the mother returns and the stranger leaves for the second time. The primary focus is on the child’s proximity- and contact-seeking behavior, contact-maintaining behavior, resistant behavior, and avoidant behavior during the two reunion episodes (5 and 8). Secure (B), insecure-avoidant (A), and insecure-resistant (C) classifications were obtained using Ainsworth’s tripartite classification system (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). The third author who trained and achieved reliability through the University of Minnesota workshop coded the Strange Situations. In the present study, inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s K) on 22 (15.3%) tapes was .73. A total of 94 (65.3%) infants were classified as secure, 25 (17.4%) as insecure-avoidant, 8 (5.6%) as insecure-resistant.

2.2.3. Child temperament (12 and 18 months)

Child temperament was measured using the Infant Behavior Questionnaire–Revised (IBQ-R; Rothbart & Gartstein, 2000) at 12 months, and the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (ECBQ; Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, 2006) at 18 months. The IBQ-R is a 191-item measure of infant (3 to 12 months) temperament. Parents rated each item on a scale of 0 to 7, in which 0 is “not applicable”, 1 is their infant “never engages in the behavior”, and 7 is their infant “always engages in the behavior”. The IBQ-R yields 14 subscales and 3 higher-order factors of Surgency/Extraversion, Negative Affectivity, and Orienting/Regulation (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003). Surgency/Extraversion is comprised of the subscales of approach, vocal reactivity, high intensity pleasure, smiling and laughter, activity level, and perceptual sensitivity (α = .78). Negative Affectivity includes the subscales of sadness, distress to limitations, fear, and falling reactivity (α = .61). Orienting/Regulation is the combination of the subscales of low intensity pleasure, cuddliness, duration of orienting, and soothability (α = .64).

The ECBQ is a 201-item measure of child (18 to 36 months) temperament. Similar to the IBQ, a 0 to 7 rating scale is used for all items, and 18 subscales and 3 higher-order factors can be derived (Putnam et al., 2006). The Surgency/Extraversion factor includes the subscales of impulsivity, activity level, high intensity pleasure, sociability, and positive anticipation (α = .62). Negative Affectivity includes the discomfort, fear, sadness, frustration, soothability (reverse-coded), motor activation, perceptual sensitivity, and shyness subscales (α = .74). The Orienting/Regulation factor is comprised of the subscales of inhibitory control, attentional shifting, low intensity pleasure, cuddliness, and attentional focusing (α = .71). The temperament factor of Negative Affectivity indicating child temperamental reactivity was included as a moderator in the present study.

2.2.4 Infant emotion regulation (12 and 18 months)

At 12 and 18 months, infants and mothers completed the Toy Removal Task (Stifter & Braungart, 1995). Infants were seated in a high chair with the mothers seated slightly to the side of the infant. For 90 seconds, the infants and mothers played with a toy (Busy Box). Mothers were then instructed to get up from her seat, remove the toy from the infant and place it on the chair so that the toy was in the infant’s sight but out of reach. For the next two minutes, mothers did not look at or respond to their infant; instead, they engaged in conversation with a research assistant. This segment of the task was designed to emulate situations when the mother’s attention is distracted away from the infant, such as when she answers the phone. The toy removal episode was cut short if the infant engaged in 20 seconds of hard crying. After two minutes of toy removal or 20 seconds of hard crying, whichever came first, mothers were asked to return the toy to the infant, but also to not interact with her infant for one minute, again engaging in conversation with a research assistant. At the end of the toy return episode, mothers resumed interaction with their infants. The average length of the toy removal episode was 113.6 seconds (SD = 26.8) at 12 months, and 111.6 seconds (SD = 28.2) at 18 months.

For every 5 seconds of the toy removal episode, six regulatory strategies were scored (Stifter & Braungart, 1995). Orienting was scored when the infant’s eyes were focused on the environment or down on their own body for one second or longer. When the infant looked at or towards the mother, looks to mother was scored; when the infant looked at the toy, looks to toy was scored. Self-comforting was scored when the infant engaged in repetitive fine motor movements including sucking on fingers, rubbing the face, stroking head or ears, and clasping clothes. Avoidance was scored when the infant had an arched back, pushed back against the high chair, strained forward, and physically turned the head away. Tension reduction behaviors included repetitive and active banging with hands, feet, or back on the high chair.

Coders who were blind to the other study variables coded the regulatory strategies. The inter-rater reliability (ICCs) of rater pairs for 27 (10.2%) randomly-selected cases across regulatory strategies ranged .85 to .99. The scores for each of the regulatory behavior codes were summed and divided by the total number of 5-second intervals in the toy removal episode. The resulting proportion variables had a possible range of 0 to 1. The majority of infants engaged in orienting, looks to mother, and looks to toy (which were normally distributed), but only a third to two-thirds of infants engaged in self-comforting, avoidance, and tension reduction behaviors (which were positively skewed). Thus, whereas all behaviors were dichotomized and included as binary (“engaged” vs. “not engaged”) variables in analyses, only the normally distributed behaviors of orienting, looks to mother, and looks to toy were included as continuous proportion outcome variables in analyses.

2.3. Data Analysis

Logistic regression models were estimated to examine whether infants’ use of emotion regulation strategies was predicted by maternal bedtime emotional availability and infant attachment security, and whether child temperamental negative affectivity moderated the relations between emotional availability and regulatory strategies, and between attachment security and regulatory strategies. Separate logistic regression analyses were conducted at each time point: (a) concurrent relations between emotional availability, temperament, and emotion regulation at 12 months; (b) emotional availability and temperament at 12 months predicting emotion regulation at 18 months; and (c) concurrent relations between emotional availability, temperament, and emotion regulation at 18 months.

The strategies of orienting, looks to mother, and looks to toy at 12 and 18 months were included as continuous outcome variables in hierarchical multiple regression, ANOVA, and ANCOVA analyses. In order to obtain the best predictive model, the models including the significant moderators were trimmed (i.e., non-significant terms starting with the largest tail probability were removed) until only significant interaction and/or main effects remained.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.1.1. Descriptives

The descriptives for all predictor, moderator, and outcome variables are provided in Table 1. Zero-order correlations between all study variables (except for infant attachment classifications) are provided in Table 2. In addition, one-way ANOVAs indicated that there were significant differences between the three infant attachment classifications (secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant) in 12-month parent-rated negative affectivity, F(2, 126) = 8.95, p < .001. Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons indicated that insecure-resistant infants’ negative affectivity (M = 3.92, SD = .85) was rated by their parent as higher than that of insecure-avoidant (M = 2.98, SD = .63) and secure (M = 3.26, SD = .50) infants.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Maternal Bedtime Emotional Availability, Infant Temperament, and Infant Emotion Regulation Strategies) (n = 144).

| M | SD | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Availability | |||

| 12 months | 18.88 | 3.33 | .33 |

| 18 months | 18.99 | 3.66 | .39 |

| Infant Temperamental Negative Affectivity | |||

| 12 months | 3.26 | .58 | .05 |

| 18 months | 2.59 | .52 | .05 |

| Infant Emotion Regulation Strategies | |||

| Orienting | |||

| 12 months | .60 | .24 | .02 |

| 18 months | .53 | .26 | .02 |

| Looks to Mother | |||

| 12 months | .63 | .22 | .02 |

| 18 months | .62 | .22 | .02 |

| Looks to Toy | |||

| 12 months | .36 | .21 | .02 |

| 18 months | .46 | .25 | .02 |

| Self-Comforting | |||

| 12 months | .24 | .27 | .02 |

| 18 months | .18 | .25 | .02 |

| Avoidance | |||

| 12 months | .08 | .12 | .01 |

| 18 months | .19 | .22 | .02 |

| Tension Reduction | |||

| 12 months | .11 | .16 | .01 |

| 18 months | .08 | .12 | .01 |

Table 2.

Correlations between Maternal Emotional Availability, Infant Temperamental Negative Affectivity, and Emotion Regulation Strategies during Toy Removal Task at 12 and 18 months (n = 144).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional availability (12 mo.) | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Emotional availability (18 mo.) | .43*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Negative affectivity (12 mo.) | −.10 | −.10 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 4. Negative affectivity (18 mo.) | −.03 | −.09 | .51*** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 5. Orienting (12 mo.) | .15 | .02 | −.07 | −.09 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 6. Look to mom (12 mo.) | .07 | −.03 | −.06 | −.03 | −.40*** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 7. Look at toy (12 mo.) | −.07 | .14 | −.06 | .06 | −.23** | .13 | 1 | |||||||||

| 8. Self-comforting (12 mo.) | −.03 | .05 | −.08 | .05 | .05 | .13 | −.01 | 1 | ||||||||

| 9. Avoidance (12 mo.) | −.06 | −.15 | .07 | .16 | −.003 | .03 | .01 | −.10 | 1 | |||||||

| 10. Tension reduction (12 mo.) | .01 | .04 | .08 | .01 | −.12 | .08 | −.09 | −.17* | .02 | 1 | ||||||

| 11. Orienting (18 mo.) | −.002 | −.04 | .03 | −.06 | .26** | −.02 | −.11 | .04 | −.11 | −.06 | 1 | |||||

| 12. Look to mom (18 mo.) | −.10 | −.04 | .09 | .07 | −.30** | .06 | .18 | −.03 | −.04 | .06 | −.38*** | 1 | ||||

| 13. Look at toy (18 mo.) | .05 | −.07 | −.08 | −.01 | −.04 | .10 | .20* | .11 | .02 | .02 | −.45*** | −.10 | 1 | |||

| 14. Self-comforting (18 mo.) | −.14 | .10 | −.04 | .04 | .003 | −.06 | −.04 | .30** | −.08 | −.14 | −.01 | .10 | −.03 | 1 | ||

| 15. Avoidance (18 mo.) | .11 | −.16 | −.002 | .03 | .03 | −.02 | −.07 | .003 | .18* | −.06 | −.21* | .04 | .12 | −.16 | 1 | |

| 16. Tension reduction (18 mo.) | .00 | .08 | −.03 | −.12 | −.05 | .02 | .07 | −.10 | −.03 | −.07 | −.10 | .12 | −.14 | −.03 | .13 | 1 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

3.1.2. Covariates

Correlations between demographic variables (child gender, maternal age, maternal employment status, maternal marital status, family income, and number of children in the home) and child regulatory strategies indicated that child gender, maternal age, and family income were related to avoidance, looks to toy, and orienting: Male infants (M = .23) engaged in more avoidance than female infants (M = .15) at 18 months, t(123) = 2.14, p < .05); mothers’ age was negatively correlated with avoidance at 12 months, r(138) = −.21, p < .05, and positively correlated with looks to toy at 18 month, r(124) = .32, p < .001); and family income was inversely related to orienting at 18 months, r(109) = −.21, p < .05). These demographic variables were thus included as covariates in analyses for the corresponding outcome variables.

3.2. Emotional Availability as Predictor of Emotion Regulation Strategies

Contrary to expectations, maternal bedtime emotional availability at 12 and 18 month did not predict infants’ emotion regulation strategies concurrently or longitudinally (all ps > .05).

3.3. Attachment Security as Predictor of Emotion Regulation Strategies

Infant attachment security at 12 months was expected to predict infants’ use of emotion regulation strategies at 12 and 18 months. Two significant relations were found at 12 months: A one-way ANOVA indicated that secure infants (M = .60) engaged in more orienting towards the environment than insecure-resistant infants (M = .37), t = −2.69, p < .01. Also, logistic regression analyses indicated that insecure-resistant infants had a decreased log odds of 2.30 in the use of tension reduction compared to secure infants, Wald statistic = 4.44, p < .05. That is, insecure-resistant infants were less likely to engage in tension reduction behaviors than secure infants.

3.4. Temperamental Negative Affectivity as Moderator of the Relation between Emotional Availability and Emotion Regulation Strategies

Infant temperamental negative affectivity as rated by the parent was expected to moderate the relations between maternal bedtime emotional availability and infant emotion regulation strategies at 12 and 18 months. Multiple regression analyses indicated that emotional availability interacted with infant negative affectivity to predict the regulatory strategy of looks to mother at both 12 months, t = −2.23, p < .05 (f 2 = −.05), and 18 months, t = −2.46, p < .05 (f 2 = −.07). The simple slopes when infants were low on negative affectivity (−1 SD below the mean; gradient = .02, p < .01, at 12 months; gradient = .02, p < .01, at 18 months), and when infants were high on negative affectivity (+1 SD above the mean; gradient = −.01, p < .05, at 12 months; gradient = −.02, p < .01, at 18 months) were significant (Aiken & West, 1991). As can be seen in Figure 1, for 12 month old infants with lower negativity, the higher the emotional availability of the mother the more these infants looked to the mother. On the other hand, for infants rated as high in negative affectivity the greater the mother’s emotional availability the less they looked to their mothers when frustrated. The same result emerged at 18 months1. As the slopes were in opposite directions, contrastive effects, and not differential susceptibility, were indicated (Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007).

Figure 1.

Moderation of the relation between maternal bedtime emotional availability and the strategy of looks to mother by infant temperamental negative affectivity at 12 months.

3.5. Temperamental Negative Affectivity as Moderator of the Relation between Attachment Security and Emotion Regulation Strategies

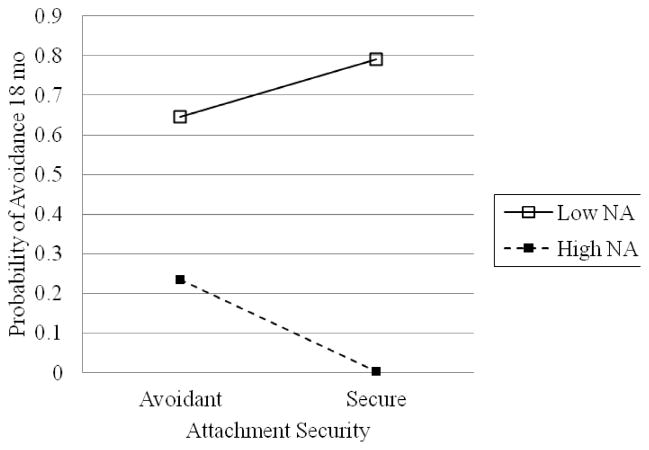

Mother-rated infant temperamental negative affectivity (at 12 months) was expected to moderate the relations between infant attachment security (at 12 months) and emotion regulation strategies at 12 and 18 months. Infant attachment security interacted with temperamental negative affectivity to predict the regulatory strategy of avoidance at 18 months. Logistic regression analyses indicated that for infants high on temperamental negative affectivity, the probability of avoidance at 18 months was higher for insecure-avoidant infants than for secure infants, Wald statistic = 5.30, p < .05 (Figure 2). The simple slope when infants were high on negative affectivity (+1 SD above the mean) were significant, gradient = −2.18, p < .05, whereas, the simple slope when infants were low on negative affectivity (−1 SD below the mean) were not, gradient = .37, p > .05.

Figure 2.

Moderation of the relation between infant attachment security and the probability of avoidance by infant temperamental negative affectivity.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the influences of mothers’ emotional availability towards their infants during bedtime, infant attachment security, and interactions between bedtime parenting quality and attachment with infant temperamental negative affectivity, on infants’ emotion regulation strategy use during a frustration task at 12 and 18 months. Whereas emotional availability was not directly related to infants’ emotion regulation strategies, infant attachment security had direct relations with infants’ orienting towards the environment and tension reduction behaviors. Although the differential susceptibility of infants high on negative affectivity was not supported, both maternal emotional availability and infant attachment security interacted with temperamental negative affectivity to predict the use of less-adaptive strategies.

Infants’ emotion regulation strategies were assessed during a frustration task that required infants to regulate their frustration levels while denied access to an attractive toy as well as mothers’ support. As infants in this frustrating situation needed to distract themselves away from the inaccessible toy and the unresponsive mother until they became accessible again, greater use of orienting (redirecting attention towards the environment), and less focus on the toy and mother (i.e., the sources of frustration) were expected to be more adaptive. In addition, as indicated in previous findings, greater use of self-comforting was considered to be more adaptive in reducing frustration, whereas greater use of avoidance and tension reduction behaviors was expected to either maintain or increase infants’ frustration (Braungart & Stifter, 1991; Crugnola et al., 2011; Diener et al., 2002; Leerkes & Wong, 2012).

In contrast to previous studies that have shown links between the quality of parent-child interactions and infant emotion regulation (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Leerkes et al., 2009; Spinrad & Stifter, 2002), mothers’ emotional availability during infant bedtime was not significantly related to infants’ regulatory strategies at 12 and 18 months. Although the reason for this null finding is not clear, it is possible that the above average levels of parenting quality found in the present community sample may have lacked enough variance to detect meaningful differences in infants’ strategy use. Despite the lack of direct relations between maternal emotional availability and infants’ regulatory strategies, the quality of bedtime parenting interacted with infant temperamental negative affectivity to predict infants’ use of the less-adaptive strategy of looks to mother. In the use of the less-adaptive strategy of looks to mother at 12 and 18 months, highly negative infants focused less on the unresponsive mother when mothers engaged in emotionally available bedtime parenting, and focused more on the unresponsive mother when mothers showed low emotional availability, than low negative infants. As the slope for low negative infants was in the opposite direction of the slope for high negative infants (and not zero), these findings suggest a contrastive effect (not differential susceptibility) of infant temperamental negative affectivity (Belsky et al., 2007). High negative infants who are more prone to experience frustration may provide more opportunities for their mothers to help with emotion regulation. If these mothers engage in emotionally available parenting that responds sensitively to these infants’ emotional cues, structures adaptive ways of regulating emotions, and refrains from intrusive/hostile responses, these infants may be better able to independently use strategies that would help them regulate their frustration. Having prior experiences of high emotional availability during the bedtime context may enable these high negative infants to focus less on the mother whose attention is temporarily distracted away from the infant. On the other hand, the positive relation between emotional availability and looks to mother for low negative infants is a more puzzling finding. Infants who are less likely to get frustrated may rely more on their mothers’ assistance during frustrating situations if their mothers typically engage in emotionally available parenting, and less so if parenting quality is low.

As a secure attachment relationship indicates a history of positive interactions during which the mother adequately met the infants’ regulatory needs and provided assistance in regulating emotions, secure infants were expected to engage in more adaptive regulatory strategies than insecure infants (Cassidy, 1994; Sroufe, 1995, 2005; Roque Verrísimo, Fernandes, & Rebelo., 2013; Thompson, 2008). As expected and consistent with previous studies (e.g., Leerkes & Wong, 2012), secure infants used the adaptive strategy of orienting towards the environment more than insecure-resistant infants. This finding suggests that infants with secure attachment were better able to regulate their frustration through shifting their attention towards the environment, and that a history of positive interactions with mothers was directly predictive of infants’ more adaptive strategy use. Contrary to expectations and previous findings, insecure-resistant infants were less likely to engage in the less-adaptive strategy of tension reduction compared to secure infants. One potential explanation for this unexpected finding may be that although insecure-resistant infants have been found to display higher levels of tension reduction behaviors (typically measured during the Strange Situation procedure in previous studies), they are also most prone to high levels of distress (Braungart & Stifter, 1991), compared to insecure-avoidant and secure infants. It may be that when faced with a frustrating situation in which the mother is purposely unresponsive, insecure-resistant infants may become too distressed to engage in any regulatory strategy (Braungart-Rieker & Stifter, 1996; Calkins & Johnson, 1998). That mothers in the present study rated insecure-resistant infants higher on temperamental negative affectivity than insecure-avoidant and secure infants lends support to this explanation.

The hypothesis that insecure infants would use more less-adaptive strategies compared to secure infants, only among highly negative infants, was supported. At 18 months, insecure-avoidant infants with high negative affectivity were more likely to engage in the less-adaptive strategy of avoidance, than secure infants with high negative affectivity. For highly negative infants, secure attachment provided benefits such that infants were less likely to use less-adaptive avoidance strategies (e.g., arching back, pushing back against the high chair) when frustrated, whereas insecure attachment increased the likelihood of such avoidance strategies.

A primary goal of the present study was to examine whether temperamentally reactive infants (i.e., those infants who are high on negative affectivity) were differentially susceptible, for better and for worse, to maternal emotional availability and attachment security in relation to their emotion regulation abilities. Although the findings discussed above indicated the moderating role of infant temperamental negative affectivity in the use of two strategies that were less adaptive in regulating frustration, they did not provide support for the differential susceptibility of infants high on negative affectivity during the toy removal episode of the frustration task. When the mother-infant relationship quality was high, infants rated as high on negative affectivity focused less on the unresponsive mother and engaged in less avoidance behaviors, whereas they engaged in more of these less-adaptive strategies when parent-infant relationship quality was low. In contrast, among infants who were low on negative affectivity, the strategy of looks to mother was positively related to maternal emotional availability, and avoidance strategies did not differ by attachment classification. It may be that for these low negative infants who are less likely to get frustrated, maternal emotional availability and attachment security has less straightforward relations with emotion regulation strategy use during a frustration task.

One limitation of the present study is the homogenous sample of primarily middle-class Caucasian families, which limits the generalizability of the findings. It will be important for future research to address whether these findings are relevant to more diverse samples. Another limitation is the lack of power to detect significant relations due to the (a) small numbers of infants with insecure-resistant (6.3%) and insecure-avoidant (19.7%) classifications, and (b) inability to include the strategies of self-comforting, avoidance and tension reduction as continuous variables. More comparable numbers of insecure-resistant, insecure-avoidant, and secure infants may reveal relations between attachment security, temperamental negative affectivity, and emotion regulation strategies of infants that were expected but not found in the present study. In addition, only mother-rated infant temperament was included. Although mothers’ perceptions of their infants’ temperament have been found to relate to parenting quality and child outcomes, it may be important to include objective measures of infant temperament in future work. Finally, the findings are limited to infant’s relationships with their mothers. More work needs to be done on other external factors, such as fathers, siblings, daycare, and peer groups, that may influence the emotion regulation abilities of infants.

The present study adds to the literature by examining both maternal emotional availability during the less-studied context of infant bedtime and infant attachment security as predictors of infant emotion regulation strategies. As well, the differential susceptibility of temperamentally reactive infants was examined, considering the moderating role of infant characteristics in infants’ emotional development. The findings point to the complex relations between parenting quality, infant attachment security, and infant reactive temperament in relation to the specific strategies that infant engage in when they experience frustration. Clearly, there is still a wealth of knowledge to be gained with regards to the development of emotion regulation in children. Future studies might further explore how the adaptiveness of particular regulatory strategies may depend on the specific “goals” of the particular situation that infants are in; determine whether and how disorganized attachment (characterized by atypical emotional reactions and bizarre behaviors; Main & Solomon, 1986) relates to specific emotion regulation strategies; and conduct cross-cultural studies that can provide insights into the universal and culture-specific processes of emotion regulation in the first years of life.

We examine infants’ emotion regulation strategies during a frustration task.

Infant attachment security directly predicts regulatory strategies.

Maternal emotional availability and infant attachment security interact with infant reactive temperament to predict less adaptive strategy use.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Albert M. Kligman Graduate Fellowship awarded to the first author, and a NIH grant (R01-HD052809) awarded to the fourth author. We thank the families who participated in this study, and the graduate and undergraduate students for their assistance in data collection and coding.

Footnotes

The figure at 18 months looked similar to that at 12 months and was thus not included.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ainsworth M. Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist. 1979;34(10):932–937. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth M, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The developmental and evolutionary psychology of intergenerational transmission of attachment. In: Carter CS, Ahnert L, Grossmann KE, Hrdy SB, Lamb ME, Porges SW, Sachser N, editors. Attachment and Bonding: A New Synthesis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005. pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: Differential Susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16(6):300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z. Emotional availability: Conceptualization and research findings. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:104–114. doi: 10.1037/h0087711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z, Robinson J, Emde RN. Unpublished manual. 3. Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University; Fort Collins, CO: 1998. Emotional availability scales. [Google Scholar]

- Braungart JM, Stifter CA. Regulation of negative reactivity during the Strange Situation: Temperament and attachment in 12-month-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 1991;14(3):349–364. doi: 10.1016/0163-6383(91)90027-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker J, Stifter CA. Infants’ responses to frustrating situations: Continuity and change in reactivity and regulation. Child Development. 1996;67(4):1767–1769. doi: 10.2307/1131730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges LJ, Grolnick WS. The development of emotional self-regulation in infancy and early childhood. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Social development. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Fear and anger regulation in infancy: Effects on the temporal dynamics of affective expression. Child Development. 1998;69:359–374. doi: 10.2307/1132171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Johnson MC. Toddler regulation of distress to frustrating events: Temperamental and maternal correlates. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:379–395. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(98)90015-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Leerkes EM. Early attachment processes and the development of emotional self-regulation. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory and applications. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2010. pp. 355–373. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Smith CL, Gill KL, Johnson MC. Maternal interactive style across contexts: Relations to emotional, behavioral, and physiological regulation during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1998;7(3):350–369. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2–3):228–283. doi: 10.2307/1166148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. The nature of the child’s ties. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, McBride-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(4):598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Dennis TA, Smith-Simon KE, Cohen LH. Preschoolers’ emotion regulation strategy understanding: Relations with emotion socialization and child self-regulation. Social Development. 2009;18(2):324–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00503.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crugnola CR, Tambelli R, Spinelli M, Gazzotti S, Caprin C, Albizzati A. Attachment patterns and emotion regulation strategies in the second year. Infant Behavior & Development. 2011;34:136–151. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ML, Mangelsdorf SC. Behavioral strategies for emotion regulation in toddlers: Associations with maternal involvement and emotional expressions. Infant Behavior and Development. 1999;22(4):569–583. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(00)00012-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ML, Mangelsdorf SC, McHale JL, Frosch CA. Infants’ behavioral strategies for emotion regulation with fathers and mothers: Associations with emotional expressions and attachment quality. Infancy. 2002;3(2):153–174. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9(4):241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC. Mothers’ emotional expressivity and children’s behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children’s regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:475–490. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekas NV, Braungart-Rieker JM, Lickenbrock DM, Zentall SR, Maxwell SM. Toddler emotion regulation with mothers and fathers: Temporal associations between negative affect and behavioral strategies. Infancy. 2011;16(3):266–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2010.00042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutionary-neurodevelopmental theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:7–28. doi: 10.1017/S095457941000060X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Easterbrooks MA. Assessing emotional availability in early development. In: Frankenburg WK, Emde RN, Sullivan JW, editors. Early identification of children at risk: An international perspective. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Greenbaum CW, Yirmiya N. Mother–infant affect synchrony as an antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:223–231. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development. 2003;26:64–86. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(02)00169-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt A, Denham SA, Dunsmore J. Affective social competence. Social Development. 2001;10:79–119. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, Zalewski M. Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(3):251–301. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan N, Carter AS. Mother-infant reengagement following the still-face: The role of maternal emotional availability in infant affect regulation. Infant Behavior and Development. 1996;19:359–370. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(96)90034-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A development view. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25(3):343–354. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.3.343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Wong MS. Infant distress and regulatory behaviors vary as a function of attachment security regardless of emotion context and maternal involvement. Infancy. 2012;17(5):455–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Blankson AN, O’Brien M. Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress on social-emotional functioning. Child Development. 2009;80:762–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little C, Carter AS. Negative emotional reactivity and regulation in 12-month-olds following emotional challenge: Contributions of maternal-infant emotional availability in a low-income sample. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26(4):354–368. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Moran G, Schuengel C, Pederson DR, Otten R. Unresolved maternal attachment representations, disrupted maternal behavior and disorganized attachment in infancy: Links to toddler behavior problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(10):1042–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins EC, Soares I, Martins C, Tereno S, Osório A. Can we identify emotion over-regulation in infancy? Associations with avoidant attachment, dyadic emotional interaction and temperament. Infant and Child Development. 2012;21:579–595. doi: 10.1002/icd.1760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16(2):361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Cassidy J, Burks VM, Carson JL, Boyum L. Familial contributions to peer competence among young children: The role of interactive and affective processes. In: Parke RD, Ladd GW, editors. Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development. 2006;29(3):386–401. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikes HA, Thompson RA. Family emotional climate, attachment security and young children’s emotion knowledge in a high risk sample. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2006;24:89–104. doi: 10.1348/026151005X70427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roque L, Verrísimo M, Fernandes M, Rebelo M. Emotion regulation and attachment: Relationships with secure base, during different situational and social contexts in naturalistic settings. Infant Behavior and Development. 2013;36:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Gartstein MA. Infant Behavior Questionnaire – Revised: Items by Scale. University of Oregon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Tikotsky L, Scher A. Parenting and infant sleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2010;14(2):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Stifter CA. Maternal sensitivity and infant emotional reactivity: Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Marriage and Family Review. 2002;34(3–4):243–263. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n03_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7(4):349–367. doi: 10.1080/14616730500365928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Waters E. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development. 1977;48(4):1184–1199. doi: 10.2307/1128475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, Braungart JM. The regulation of negative reactivity in infancy: Function and development. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(3):448–455. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stupica B, Sherman LJ, Cassidy J. Newborn irritability moderates the association between infant attachment security and toddler exploration and sociability. Child Development. 2011;82(5):1381–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Kim B-R. Infants and pre-school children: Observational assessments of attachment, a review and discussion of clinical applications. In: Holmes P, Farnfield S, editors. Attachment: The Guidebook to the Assessment of Attachment. London: Routledge; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Kim BR, Mayer G, Countermine M. Maternal emotional availability at bedtime predicts infant sleep quality. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(3):307–315. doi: 10.1037/a0019306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2–3):25–52. doi: 10.2307/1166137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Early attachment and later development: Familiar questions, new answers. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 348–365. [Google Scholar]

- Ursache A, Blair C, Stifter C, Voegtline K. Emotional reactivity and regulation in infancy interact to predict executive functioning in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(1):127–137. doi: 10.1037/a0027728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Integrating temperament and attachment: The differential susceptibility paradigm. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of temperament. New York: Guilford; 2012. pp. 403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Waters SF, Virmani EA, Thompson RA, Meyer S, Raikes HA, Jochem R. Emotion regulation and attachment: Unpacking two constructs and their association. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9163-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]