Abstract

Background

Data on changes in metabolic syndrome (MetS) status in HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy (ART) are limited.

Method

MetS was assessed at ART initiation and every 48 weeks on ART in ART-naïve HIV-infected individuals from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials (ALLRT) cohort. MetS, defined using the ATP-III criteria, required at least three of: elevated fasting glucose, hypertension, elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol. Prevalence of MetS and the individual criteria were compared between ART initiation and during follow-up using McNemar’s test.

Results

At ART initiation, 450 (20%) ALLRT participants had MetS. After 96 weeks of ART, 37% of the 411 with MetS at ART initiation and with available data at this time-point did not meet the MetS criteria. Among these participants, there was a dramatic decline in the proportion with low HDL (95% versus 26%, p<0.0001). Among the 63% that continued to meet MetS criteria at week 96, the proportion with ≥4 criteria was higher at week 96 compared to ART initiation (48% versus 40%, p=0.03); at week 96, the proportion with high triglycerides was greater (87% versus 69%, p<0.0001) as was the proportion with high glucose (59% versus 42%, p<0.0001).

Conclusion

One in five ART-naïve subjects met criteria for MetS at ART initiation. While more than half of these individuals continued to have MetS after 96 weeks of ART, 37% with MetS at ART initiation no longer met criteria for MetS; this decrease was driven largely by increases in HDL cholesterol.

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of central obesity and metabolic abnormalities that confers an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes 1. The diagnosis of MetS requires the presence of at least three of the following conditions: elevated fasting glucose, hypertension, elevated waist circumference, elevated triglycerides, and low HDL cholesterol. The age-adjusted prevalence of MetS in the general adult U.S. population is 34.3% 2.

The development of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treatment of HIV infection has led to fewer AIDS-related complications and better prognosis for HIV-infected patients. However, HIV-infected patients are now experiencing more non-AIDS conditions such as heart disease and diabetes 3. A number of metabolic and morphological changes have also been reported in these individuals; these changes have been attributed to specific ART, the HIV virus and lifestyle factors 4,5, and directly impact the criteria that define MetS.

We recently published an analysis of MetS prevalence, incidence and associated factors in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials (ALLRT), a large US cohort of HIV-infected individuals starting initial ART regimens 6. In our cohort, the prevalence of MetS at ART initiation was 20%. Similar prevalence estimates have been reported from other populations of HIV-infected adolescents and adults. However, none of the previous reports describing MetS in HIV have examined the progression of MetS on long term ART. The objective of this analysis was to examine the change in prevalence of MetS after ART among HIV-infected individuals with MetS at ART initiation.

Methods

Study population

ALLRT is a prospective cohort of >5000 HIV-infected participants (age ≥13 years) randomized to receive ART regimens, immune-based therapies or treatment strategies in selected ACTG clinical trials 7. ACTG sites that enrolled participants to ALLRT received approval by their designated institutional review boards to conduct ALLRT, and all ALLRT participants provided written informed consent.

The source population included 2,554 individuals who enrolled in ALLRT from three ACTG parent trials (A5095, A5142 and A5202) 8–10; all these individuals were ART-naïve when they enrolled in their parent trial and were randomized to initiate therapy with different ART regimens. The ART regimens used in these trials included either: 1) three nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), 2) two/three NRTIs with a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or a boosted-protease inhibitor (PI), or 3) an NNRTI with a boosted PI.

The baseline visit was the parent trial entry visit (at ART initiation). When individuals were enrolled in the parent trial, visits were scheduled according to the parent trial protocol. When the parent trial ended, data collection continued according to the ALLRT protocol. Data were recorded by the study site staff using standard ACTG forms. ACTG sites that enrolled participants to ALLRT received approval by their designated institutional review boards to conduct this study, and all ALLRT participants provided written informed consent. For this analysis, we only included individuals who had MetS (defined below) at ART initiation.

Definition of metabolic syndrome (MetS)

Based on the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATPIII) criteria 1, MetS was defined as the presence of three or more of the following components: 1) waist circumference >88 cm in women or >102 cm in men; 2) blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg systolic or ≥85 mm Hg diastolic or use of antihypertensive medications; 3) triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL or use of lipid-lowering medications (niacin, fenofibrate, and gemfibrozil); 4) fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL, physician diagnosed diabetes or use of diabetic medications; 5) high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) <50 mg/dL in women or <40 mg/dL in men.

According to the ALLRT protocol, blood pressure readings, fasting lipid panel and glucose were assessed every 16 weeks, and waist circumference was measured every 48 weeks. For 800 individuals, the first available waist circumference measurement was within 16 weeks after baseline due to the timing of their ALLRT entry visit; for these individuals, the waist circumference at week 16 was considered as baseline.

At ART initiation, individuals with three or more MetS components were defined as cases of MetS, (even if they were missing data on other components). Those without MetS at ART initiation were categorized as one of the following: 1) those with two components and no missing data; 2) those with one component and missing data on ≤1 component, and; 3) those with no components and missing data on ≤2 components. At ART initiation, individuals with missing data on one or more of the MetS components, and who could not be classified as having or not having MetS, were excluded from the study population. Using the methods described above, MetS was also assessed every 48 weeks for 240 weeks (approximately 5 years) after ART initiation among subjects with MetS at baseline.

Analysis

Data from the ALLRT cohort through June 30, 2011 was used for this analysis. Prevalence of MetS was calculated as the number of cases divided by the total evaluable population (individuals that could be classified as having MetS or not having MetS, as described in Methods). Prevalence of MetS and the individual criteria were compared between baseline and at follow-up using the McNemar’s test. We also evaluated associations using chi-square tests as well as logistic regression (univariate and adjusted) between demographic and HIV-associated factors at ART initiation and MetS status during follow-up at week 96 and week 240. Covariates examined included age (years), sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, history of cigarette smoking, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), family history of CVD, HIV-1 RNA viral load (copies/mL), CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) and type of ART regimen (categorized as stavudine (d4t) or zidovudine (AZT) use, tenofovir (TDF) or abacavir (ABC) use, no NRTI use; lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) use, atazanavir/ritonavir (ATV/r) use, no PI use). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Study population

At ART initiation (baseline), 450 (20%) of the 2247 ALLRT participants had MetS; 307 (12%) participants were excluded because of insufficient data to classify MetS. Table 1 shows the proportion of individuals with follow-up data, the proportion of individuals with evaluable data for MetS, and the MetS status after 48, 96, 144, 192 and 240 weeks of ART. After 96 weeks of ART, 411 (91%) were still in follow-up. Among these 411 individuals, 91% had evaluable data, and 63% of those with evaluable data continued to meet the criteria for MetS. At each subsequent time-point from week 96 to week 240, the proportion of contributing individuals with MetS remained between 50% and 60%.

Table 1.

Disposition and MetS status of ALLRT subjects with MetS at ART initiation

| ART initiation | Week 48 | Week 96 | Week 144 | Week 192 | Week 240 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals in follow-up | 450 | 433 | 411 | 370 | 338 | 250 |

| Number of individuals with evaluable dataa | 450 | 405 | 378 | 310 | 263 | 185 |

| Number (%) with MetSb | 450 | 242 (60) | 239 (63) | 176 (53) | 156 (59) | 104 (56) |

| Number (%) without MetSb | - | 163 (40) | 139 (37) | 134 (47) | 107 (41) | 81 (44) |

individuals that could be classified as having or not having MetS as described in the Methods section.

percents are calculated for those with evaluable data

Since the proportion with complete data was less than 90% after week 96, the main analysis and results below are presented on week 96. However, we also repeated each analysis at week 240; results were similar at both time points.

Number of MetS criteria at ART initiation and during follow-up

Among the 450 cases of MetS at ART initiation, 70%, 24% and 6% had 3, 4 and 5 MetS criteria, respectively. Among those with MetS during follow-up, the proportion with ≥4 criteria increased (Table 2). Among those with MetS at week 96 (N=239), the proportion with ≥4 criteria was higher at week 96 versus at ART initiation (48% versus 40%, McNemar’s test p=0.03). Among those without MetS at week 96, more than 50% had ≤1 MetS criteria. Similarly, among those with MetS at week 240, the proportion with ≥4 criteria was higher at week 240 versus at ART initiation.

Table 2.

Distribution of number of MetS criteria at week 96 and week 240, among subjects with MetS at ART initiation.

| Week 0 status | Week 96 status | Week 240 status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of MetS criteria | MetS at ART initiation (N=450) | MetS at ART initiation and week 96 (N=239) | MetS at ART initiation and no MetS at week 96 (N=139) | MetS at ART initiation and week 240 (N=104) | MetS at ART initiation and no MetS at week 240 (N=81) | ||||

| ART initiation | ART initiation | Week 96 | ART initiation | Week 96 | ART initiation | Week 96 | ART initiation | Week 96 | |

| 0 | - | - | - | - | 27 (19) | - | - | - | 18 (22) |

| 1 | - | - | - | - | 51 (37) | - | - | - | 25 (31) |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | 61 (44) | - | - | - | 38 (47) |

| 3 | 315 (70) | 143 (60) | 123 (52) | 120 (86) | - | 60 (58) | 54 (52) | 59 (73) | - |

| 4 | 108 (24) | 73 (30) | 86 (36) | 17 (12) | - | 32 (31) | 38 (36) | 21 (26) | - |

| 5 | 27 (6) | 23 (10) | 30 (12) | 2 (1) | - | 12 (11) | 12 (12) | 1 (1) | - |

We examined the distribution of the various combinations of MetS criteria among the individuals with MetS at ART initiation and during follow-up. At ART initiation, the most common combination among the cases included high blood pressure, high triglycerides and low HDL (18%), followed by the combination of high waist circumference, high triglycerides and low HDL (16%). At week 96, the most common combination included all five criteria (12%); the second most common combination included all criteria except high blood glucose (11%).

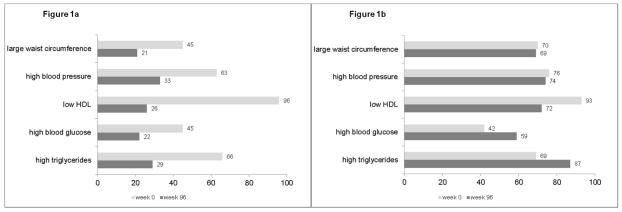

Status of MetS criteria during follow-up among those who did not continue to exhibit MetS

We compared the proportion of each criterion among those without MetS during follow-up (Figure 1a). Among the 139 cases with MetS at ART initiation but not at week 96, the proportion of all the MetS criteria decreased. The largest decrease was the proportion of those with low HDL (96% at ART initiation and 26% at week 96); the median (interquartile (IQR)) for change in HDL in this group was 12 mg/dl (5, 18) (Table 3). Similarly, proportions of those with each MetS criteria were lower at week 240 than at ART initiation (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Distribution (%) of MetS criteria at week 0 and 96 among 139 subjects who had MetS only at ART initiation.

Note: all McNemar’s p-values comparing proportions at ART initiation to week 96 <0.0001

Figure 1b. Distribution (%) of MetS criteria at week 0 and 96 among 239 subjects who had MetS at both time-points.

Note: McNemar’s p-values comparing proportions at ART initiation to week 96 for triglycerides, glucose and HDL <0.0001; p-values for waist circumference and blood pressure>0.1

Table 3.

Levels (median (IQR)) of MetS criteria by MetS status at week 96.

| MetS at ART initiation (N=450) | Follow-up at week 96 (N=378) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MetS at ART initiation and week 96 (N=239) | MetS at ART initiation and no MetS at week 96 (N=139) | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||

| ART initiation | 101 (91, 109) | 104 (96, 112)* | 93 (85, 104)* |

| Week 96 | 101 (93, 110) | 106 (98, 114)* | 93 (86, 100)* |

| Change at week 96 | 1.5 (−3, 6) | 2 (−3, 8) † | 0 (−5, 4) † |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| ART initiation | 130 (120, 139) | 131 (120, 141) † | 128 (120, 136) † |

| Week 96 | 127 (118, 138) | 130 (120, 140)* | 122 (113, 130)* |

| Change at week 96 | −1 (−11, 7) | −1 (−10, 8) † | −3 (−12, 4) † |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| ART initiation | 82 (75, 90) | 83 (76, 90) † | 81 (74, 88) † |

| Week 96 | 80 (74, 86) | 80 (75, 87)‡ | 78 (72, 81) ‡ |

| Change at week 96 | −3 (−9, 4) | −2 (−9, 5) ‡ | −5 (−9, 2) ‡ |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | |||

| ART initiation | 32 (27, 37) | 32 (27, 37) † | 34 (29, 38) † |

| Week 96 | 39 (33, 48) | 37 (31, 44)* | 45 (40, 54)* |

| Change at week 96 | 8 (2, 13) | 6 (2, 11)* | 12 (5, 18)* |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | |||

| ART initiation | 92 (83, 104) | 93 (84, 107) † | 89 (80, 103) † |

| Week 96 | 97 (88, 108) | 102 (92, 114)* | 90 (83, 95)* |

| Change at week 96 | 5 (−5, 14) | 6 (−3, 17) † | 1.5 (−8, 10) † |

| Fasting triglycerides (mg/dl) | |||

| ART initiation | 180 (126, 235) | 184 (131, 237) † | 175 (125, 227) † |

| Week 96 | 199 (135, 285) | 223 (171, 301)* | 135 (98, 201)* |

| Change at week 96 | 19 (−39, 93) | 47 (−12, 131)* | −21 (−89 30)* |

Comparison between patients with MetS at ART initiation and week 96 and patients with MetS at ART initiation and no MetS at week 96:

p-value<0.0001;

p<0.05;

p>0.05

Status of MetS criteria during follow-up among those who continued to exhibit MetS

We compared the proportion of each MetS criterion among those with MetS at ART initiation and during follow-up. Figure 1b shows the proportions at ART initiation and week 96. The proportion of those with high triglycerides was greater at week 96 compared to ART initiation (87% versus 69%, McNemar’s test p<0.0001); median (IQR) for change in triglycerides at week 96 was 47 mg/dl (−12, 131) (Table 3). Similarly, the proportion of those with high glucose was greater at week 96 than at ART initiation (59% versus 42%, McNemar’s test p<0.0001). In contrast, the proportion of those with low HDL was higher at ART initiation than week 96 (93% versus 72%, McNemar’s test p<0.0001); median (IQR) for change in HDL at week 96 was 6 mg/dl (2, 11). The proportion of those with large waist circumference and those with high blood pressure was similar at ART initiation and week 96 (p=0.4 and p=0.6, respectively).

When we compared proportions at ART initiation with week 240, similar results were obtained; the proportion of those with high triglycerides and those with high glucose were higher at week 240 compared to ART initiation; proportions of those with low HDL were lower, and the proportions with high blood pressure and those with high waist circumference were similar at week 240 compared to ART initiation (data not shown).

Factors associated with MetS during follow-up

Table 4 shows demographic and HIV-associated characteristics for the 450 individuals who had MetS at ART initiation; 55% were >40 years of age, 73% were male and 47% were white, non-Hispanic.

Table 4.

Baseline (pre-ART) characteristics of HIV-infected ART-naive individuals with MetS at ART initiation.

| MetS at ART initiation (N=450) | Follow-up at week 96 (N=378) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetS at ART initiation and week 96 (N=239) | MetS at ART initiation and no Mets at week 96 (N=139) | Chi-square p-value | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤30 | 57 (12) | 26 (11) | 19 (14) | 0.8 |

| 31–40 | 144 (33) | 76 (32) | 43 (31) | |

| 41–50 | 166 (36) | 91 (38) | 53 (38) | |

| >50 | 83 (19) | 46 (19) | 24 (17) | |

| Male sex | 330 (73) | 174 (73) | 103 (74) | 0.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| white non-Hispanic | 212 (47) | 118 (49) | 64 (46) | 0.4 |

| black non-Hispanic | 120 (27) | 57 (24) | 44 (32) | |

| Hispanic | 108 (24) | 59 (25) | 29 (21) | |

| other | 10 (2) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Education (years) | ||||

| <12 | 73 (19) | 44 (18) | 29 (21) | 0.5 |

| 12 | 90 (24) | 61 (26) | 29 (21) | |

| 13–15 | 129 (34) | 84 (35) | 45 (32) | |

| >=16 | 86 (23) | 50 (21) | 36 (26) | |

| Family History of CVD | 109 (24) | 58 (24) | 26 (19) | 0.2 |

| Smoking history | 265 (59) | 130 (54) | 90 (65) | 0.05 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 29.3 (25.6, 32.8) | 31.7 (28.1, 35.7) | 27.2 (24.2, 29.9) | |

| <25 | 92 (21) | 34 (14) | 45 (32) | <0.0001 |

| 25–29 | 163 (36) | 75 (31) | 61 (44) | |

| ≥30 | 194 (43) | 129 (54) | 33 (24) | |

| CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) | ||||

| ≤50 | 78 (17) | 34 (14) | 24 (17) | 0.7 |

| 51–200 | 112 (25) | 67 (28) | 34 (25) | |

| 201–350 | 147 (33) | 79 (33) | 47 (34) | |

| 351–500 | 74 (16) | 43 (18) | 21 (15) | |

| >500 | 39 (9) | 16 (4) | 13 (9) | |

| HIV-1 RNA (copies/mL) | ||||

| <10,000 | 55 (12) | 29 (12) | 20 (14) | 0.3 |

| 10,000–100,000 | 259 (58) | 142 (59) | 72 (52) | |

| >100,000 | 136 (29) | 68 (28) | 47 (34) | |

| Parent triala | ||||

| A5095 | 120 (27) | 56 (23) | 46 (33) | 0.1 |

| A5142 | 105 (23) | 62 (26) | 33 (24) | |

| A5202 | 225 (50) | 121 (51) | 60 (43) | |

| Initial NRTI regimen | ||||

| d4t or AZT | 92 (20) | 48 (20) | 33 (24) | 0.2 |

| TDF or ABC | 328 (73) | 170 (71) | 100 (72) | |

| No NRTI | 29 (7) | 21 (9) | 6 (4) | |

| Initial PI regimen | ||||

| LPV/r | 65 (14) | 40 (17) | 20 (14) | 0.3 |

| ATV/r | 115 (26) | 63 (26) | 29 (21) | |

| No PI | 270 (60) | 136 (57) | 90 (65) | |

Data are number (%) unless indicated. MetS, metabolic syndrome; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CVD, cardiovascular disease; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; d4T:stavudine; AZT: zidovudine; TDF: tenofovir; ABC:abacavir; PI, protease inhibitor; LPV/r: lopinavir/ritonavir; ATV/r:atazanavir/ritonavir.

One subject missing data on baseline BMI; One subject missing data for family history of CVD.

A5095 enrollment period: 2001–2002; A5142 enrollment period: 2003–2004; A5202 enrollment period: 2005–2007.

BMI increased by a median of 0.8 kg/m2 (Q1, Q3: −1.0, 2.8) from ART initiation to week 96 among everyone who had MetS at initiation. The increase in BMI (median increase 1.2 kg/m2 vs 0.3 kg/m2, p=0.003) and the proportion of obese (BMI ≥30) individuals (54% versus 24%, p<0.0001, Table 4) was higher among the 239 cases with MetS at ART initiation and week 96 compared to the 172 cases with MetS only at ART initiation. In addition to BMI, waist circumference was higher at ART initiation and at week 96 among those with MetS at both time points compared to those with MetS only at ART initiation (both p-values<0.0001, Table 3).

The proportion of those on a PI-based regimen was 43% among those who had MetS at both time-points and 35% among those who only had MetS at ART initiation (Table 4); however this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.1). Among those who had MetS at both time-points, 17% were on LPV/r containing regimen and 26% were on an ATV/r containing regimen; among those with MetS only at ART initiation, 14% were on a LPV/r containing regimen and 21% were on an ATV/r containing regimen. We then examined if individual components of MetS changed in those receiving LPV/r versus ATV/r; the proportion of high triglycerides was 60% (ART initiation) and 76% (week 96) among those receiving LPV/r compared to 63% (ART initiation) and 66% (week 96) among those receiving ATV/r; the proportion of those with low HDL was 92% (ART initiation) and 45% (week 96) among those receiving LPV/r compared to 93% (ART initiation) and 66% (week 96) in those receiving ATV/r.

There was no difference in MetS status by type of NRTI-based regimen: among those with MetS at both time-points, 20% were on a d4T/AZT-containing regimen and 71% were on an ABC/TDF-containing regimen, while among those with MetS only at ART initiation, 24% and 72% were on a d4T/AZT- and ABC/TDF-containing regimen, respectively. The distribution of all other baseline characteristics was similar among those with MetS and those without MetS at week 96 (Table 4).

In univariate analysis, pre-ART CD4 count, pre-ART viral load and initial ARV regimen were not significantly associated with MetS status at week 96; however being obese pre-ART was associated with having MetS at week 96 (odd ratio=5.0, 95% CI=2.8 to 9.0). This association persisted (odds ratio=5.3, 95% CI=2.9 to 9.6) even after adjusting for traditional risk factors such as age, sex, race and smoking. We then examined change in BMI at week 96 by MetS status among those who were obese pre-ART; the median BMI change was 0.4 kg/m2 (Q1, Q3=−1.5, 3.1) and = −1.7 kg/m2 (−3.3, −0.1) among those with and those without MetS at week 96, respectively.

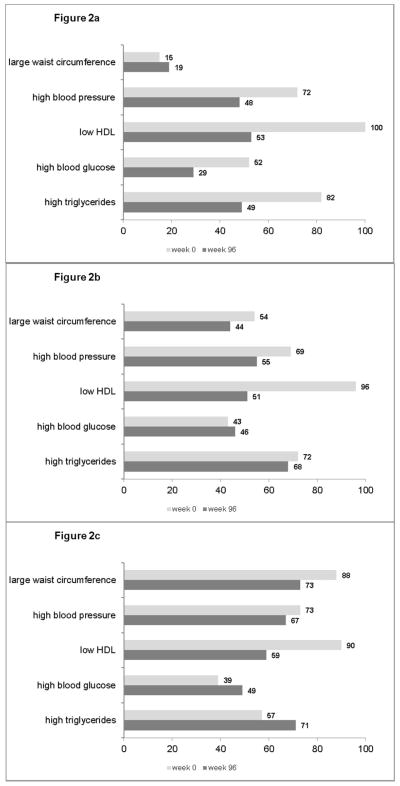

We compared the proportions of MetS criteria at ART initiation and week 96 by BMI categories at ART initiation (Figure 2a–2c). The proportions with large waist circumference, high triglycerides and high glucose were higher at week 96 among the obese group compared to those with a normal BMI. Among those who were obese pre-ART, 71% had high triglycerides at week 96 compared to 49% among those with normal BMI (p=0.001). The proportion of those with high blood glucose at week 96 was 49% and 29% in the pre-ART obese and normal BMI groups, respectively (p=0.004).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Distribution (%) of MetS criteria at week 0 and 96 among 79 subjects with baseline BMI <25

Figure 2b. Distribution (%) of MetS criteria at week 0 and 96 among 136 subjects with baseline BMI 25–29

Figure 2c. Distribution (%) of MetS criteria at week 0 and 96 among 162 subjects with baseline BMI 30+

Discussion

In a cohort of ART-naïve HIV-infected adults where one in five had MetS at ART initiation, we found that 37% of those with MetS no longer met criteria for the syndrome after 96 weeks of ART – this decline was largely driven by a decrease in the proportion of those with low HDL. Among this group, improvements in all MetS criteria were seen at week 96 including in waist circumference with the proportion meeting this criterion dropping by more than half. To our knowledge, no other study has reported on the MetS status during follow-up on ART of HIV-infected individuals with the syndrome at ART initiation.

Low HDL has been associated with untreated HIV infection 11 and both NNRTI and PI therapy can increase HDL levels 12. A recent report on lipid profiles in HIV-infected patients also showed increases in HDL after three years of therapy 13. In our study, there were no significant differences in MetS status by type of regimen, although improvements in HDL varied by BMI category. Among those with normal BMI at ART initiation, the proportion with low HDL was reduced by half after 96 weeks (100% versus 53%). In contrast, among those who were obese at ART initiation, the decline in the proportion with low HDL was not as dramatic (90% to 59%). Low HDL is often reported in obesity and is believed to be caused by an increased fractional clearance of HDL and a reduced production of the cardioprotective apolipoprotein A-1 14,15. These observations are important in light of the current obesity epidemic seen in HIV-infected subjects worldwide, including in resource-limited settings 16–18.

In the individuals who continued to exhibit MetS, the number of MetS criteria increased during 96 weeks of ART, indicating an increase in metabolic abnormalities. This finding was also supported by the concomitant increases in high triglycerides and blood glucose. Overall the group with persistent MetS at week 96 was a group that either had no improvement or did worse on all five MetS criteria.

Elevated triglycerides and increased blood glucose have been frequently associated with ART, specifically with PI-containing regimens 12. In our recent report on incident MetS, we found that use of a PI-based regimen was associated with a higher risk for development of MetS 6. In the current analysis, it appeared that there was a higher proportion of those on a PI-based regimen in the group that continued to exhibit MetS, however this difference was not statistically significant. There was no difference in MetS status by specific PI (lopinavir/ritonavir or atazanavir/ritonavir). Although ATV/r is considered to be more “metabolically friendly” than LPV/r19, both medications increase triglycerides (although the magnitude of the change is smaller with ATV/r), whereas HDL tends to increase to a lesser extent with ATV/r, such that those receiving ATV/r were more likely to still have low HDL at 96 weeks.

Previously, we have reported that high BMI is a risk factor for developing MetS in our HIV-infected cohort on ART 6. Results from the present study show that pre-ART BMI was associated with MetS status even after 96 weeks of ART; the proportion of obese individuals was higher in those who continued to exhibit MetS compared to those who did not. Further, we found that triglycerides and blood pressure were more likely to improve among those in the normal BMI group, while they were more likely to increase in the obese group. Other studies in both HIV-infected and the general population have also shown that triglycerides and blood pressure are elevated among overweight and obese persons20–22. These observations that obesity predisposes to the maintenance or development of metabolic abnormalities in HIV-infected patients initiating ART suggest that obesity may be a factor to consider before choosing an ART regimen. Our findings on the worsening metabolic levels in obese HIV-infected persons suggest that this group should be closely monitored by clinicians. Future studies should also evaluate if lifestyle changes including diet and exercise as well as other weight loss strategies that are effective in the general population can also be used for obese HIV-infected patients starting ART. In a previous trial, nutritional intervention diet based on NCEP ATP III guidelines was effective in reducing the incidence of lipid abnormalities in HIV-infected patients starting ART 23. Our data showing that in pre-ART obesity BMI decreased in those without MetS at week 96 but did not change in those with MetS at week 96 suggest that in the obese category, a small reduction in weight can lead to metabolic benefits.

Abdominal obesity, measured using waist circumference and waist-hip ratio, increases the risk of CVD and type 2 diabetes24 and is correlated with insulin resistance24. Waist circumference positively correlated with inflammatory markers such as IL-6, sTNFR-I and sTNFR-225, which have been associated with an increased risk of non-AIDS events in HIV-infected populations26. In our study, abdominal obesity measured using waist circumference was lower among those without MetS at week 96 compared to those with MetS. The role of abdominal obesity in the pathophysiology of MetS needs to be further studied in order to understand if it predicts MetS along with being part of the diagnostic criteria for MetS.

In the present study, the majority of individuals were categorized with MetS at ART initiation based on the combination of hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL. This is similar to what was observed among individuals with incident MetS in our cohort 6. After 96 weeks of ART, the most common combination among those who continued to exhibit Mets was all five criteria indicating that those with MetS appear to be getting worse. A similar conclusion can be reached by examining the individual components of MetS. Overall, the most common metabolic abnormality at ART initiation was low HDL followed by high triglycerides and high blood pressure. At week 96 among those with continued MetS, the most common metabolic abnormalities were low HDL, high triglycerides and high blood pressure; however the proportions with large waist circumference and those with high blood glucose were also high at week 96. The worsening metabolic profile of those with continued MetS in our cohort may lead to increased disease burden.

A primary strength of our study is the unique cohort of HIV-infected individuals who were treatment naïve at entry, randomized to treatment regimens in clinical trials, and rigorously monitored and followed long-term after completion of the original clinical trial. This prospectively followed cohort had scheduled visits during their parent trial and during follow-up in ALLRT which ensured that all components of MetS were collected using standardized methods at regular intervals, and blood was drawn in a fasting state. An important limitation of our study is that we did not have follow-up data on all participants. After 240 weeks, only half of the original participants had follow-up data; this was either because they were lost to follow-up or because they had not yet reached 240 weeks after ART initiation. We also did not have data on alcohol use, exercise, or nutrition/caloric intake, all of which have been shown to be associated with MetS in other studies, and could have affected the MetS status of our study participants during follow-up. And finally, our study population did not include participants who initiated ART with newer drugs such as integrase inhibitors with less adverse metabolic effects27. Future studies should evaluate if the prevalence of MetS during follow-up on ART is different for these newer regimens.

In summary, we found that 37% of HIV-infected ART-naïve individuals with MetS at ART initiation no longer have MetS by 96 weeks of therapy. A large proportion of these individuals had improvements in their metabolic profiles, particularly HDL, as well as waist circumference. The clinical relevance of this decrease in MetS and if it leads to a lower risk of CVD and diabetes needs to be evaluated in future studies28,29. On the other hand, almost two thirds of HIV-infected ARV-naïve individuals with MetS at ART initiation continued to exhibit MetS after ART initiation, and may be at greater risk for further metabolic disease complications. BMI seems to play an important role and individuals with high BMI at ART initiation were less likely to improve their MetS status and, therefore, may be at heightened risk for CVD.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank the study volunteers who participate in ALLRT/A5001, all the ACTG clinical units who enroll and follow participants, and the ACTG. We would also like to thank the A5001 protocol team. This work was supported by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI 68634, AI 38858, AI 68636, AI 38855). Dr Glesby is supported by U01 AI69419 and K24 AI078884. Dr. Shikuma is supported by NHLBI grant HL095135 (R01). Dr Haubrich is supported by NIAID grants AI27670 (UCSD ACTU), AI36214 (CFAR), and AI064086 (K24).

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Li C, Zhao G. Prevalence and correlates of metabolic syndrome based on a harmonious definition among adults in the US. Journal of diabetes. 2010;2:180–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2010.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volberding PA, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. Lancet. 2010;376:49–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fichtenbaum CJ. Metabolic abnormalities associated with HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. Current infectious disease reports. 2009;11:84–92. doi: 10.1007/s11908-009-0012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wohl DA, Brown TT. Management of morphologic changes associated with antiretroviral use in HIV-infected patients. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2008;49 (Suppl 2):S93–S100. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318186521a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan S, Schouten JT, Atkinson B, et al. Metabolic syndrome before and after initiation of antiretroviral therapy in treatment-naive HIV-infected individuals. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2012;61:381–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182690e3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smurzynski M, Collier AC, Koletar SL, et al. AIDS clinical trials group longitudinal linked randomized trials (ALLRT): rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. HIV clinical trials. 2008;9:269–82. doi: 10.1310/hct0904-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulick RM, Ribaudo HJ, Shikuma CM, et al. Triple-nucleoside regimens versus efavirenz-containing regimens for the initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:1850–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riddler SA, Haubrich R, DiRienzo AG, et al. Class-sparing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:2095–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sax PE, Tierney C, Collier AC, et al. Abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine for initial HIV-1 therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:2230–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riddler SA, Smit E, Cole SR, et al. Impact of HIV infection and HAART on serum lipids in men. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:2978–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worm SW, Lundgren JD. The metabolic syndrome in HIV. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2011;25:479–86. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duro M, Sarmento-Castro R, Almeida C, Medeiros R, Rebelo I. Lipid profile changes by high activity anti-retroviral therapy. Clinical biochemistry. 2013;46:740–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mooradian AD, Haas MJ, Wehmeier KR, Wong NC. Obesity-related changes in high-density lipoprotein metabolism. Obesity. 2008;16:1152–60. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Peng DQ. New insights into the mechanism of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in obesity. Lipids in health and disease. 2011;10:176. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amorosa V, Synnestvedt M, Gross R, et al. A tale of 2 epidemics: the intersection between obesity and HIV infection in Philadelphia. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2005;39:557–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandina Ndona M, Longo-Mbenza B, Wumba R, et al. Nadir CD4+, religion, antiretroviral therapy, incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and increasing rates of obesity among black Africans with HIV disease. International journal of general medicine. 2012;5:983–90. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S32167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malaza A, Mossong J, Barnighausen T, Newell ML. Hypertension and obesity in adults living in a high HIV prevalence rural area in South Africa. PloS one. 2012;7:e47761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina JM, Andrade-Villanueva J, Echevarria J, et al. Once-daily atazanavir/ritonavir compared with twice-daily lopinavir/ritonavir, each in combination with tenofovir and emtricitabine, for management of antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients: 96-week efficacy and safety results of the CASTLE study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2010;53:323–32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c990bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Archives of internal medicine. 2002;162:1867–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen NT, Magno CP, Lane KT, Hinojosa MW, Lane JS. Association of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome with obesity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2008;207:928–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L, et al. Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PloS one. 2010;5:e10106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazzaretti RK, Kuhmmer R, Sprinz E, Polanczyk CA, Ribeiro JP. Dietary intervention prevents dyslipidemia associated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals: a randomized trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;59:979–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haffner SM. Abdominal adiposity and cardiometabolic risk: do we have all the answers? The American journal of medicine. 2007;120:S10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.06.006. discussion S6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan SBR, Rodriguez B, Hunt PW, Wilson C, Deeks SG, Lederman MM, Landay AL, Tenorio AR. Correlates of inflammatory markers after one year of suppressive antiretroviral treatment. 21th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Boston, MA, USA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenorio AR, Zheng Y, Bosch RJ, et al. Soluble Markers of Inflammation and Coagulation but Not T-Cell Activation Predict Non-AIDS-Defining Morbid Events During Suppressive Antiretroviral Treatment. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srinivasa S, Grinspoon SK. Metabolic and body composition effects of newer antiretrovirals in HIV-infected patients. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2014;170:R185–202. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piconi S, Parisotto S, Rizzardini G, et al. Atherosclerosis is associated with multiple pathogenic mechanisms in HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive or treated individuals. Aids. 2013;27:381–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835abcc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parrinello CM, Landay AL, Hodis HN, et al. Treatment-related changes in serum lipids and inflammation: clinical relevance remains unclear. Analyses from the Women’s Interagency HIV study. Aids. 2013;27:1516–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fd8a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]