Abstract

Background

Xenograft rejection of pigs organs with an engineered mutation in the GGTA-1 gene (GTKO) remains a predominantly antibody mediated process which is directed to a variety of non-Gal protein and carbohydrate antigens. We previously used an expression library screening strategy to identify six porcine endothelial cell cDNAs which encode pig antigens that bind to IgG induced after pig-to-primate cardiac xenotransplantation. One of these gene products was a glycosyltransferase with homology to the bovine β1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (B4GALNT2). We now characterize the porcine B4GALNT2 gene sequence, genomic organization, expression, and functional significance.

Methods

The porcine B4GALNT2 cDNA was recovered from the original library isolate, subcloned, sequenced, and used to identify a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing the entire B4GALNT2 locus from the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute BACPAC Resource Centre (#AC173453). PCR primers were designed to map the intron/exon genomic organization in the BAC clone. A stable human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell line expressing porcine B4GALNT2 (HEK-B4T) was produced. Expression of porcine B4GALNT2 in HEK-B4T cells was characterized by immune staining and siRNA transfection. The effects of B4GALNT2 expression in HEK-B4T cells was measured by flow cytometry and complement mediated lysis. Antibody binding to HEK and HEK-B4T cells was used to detect an induced antibody response to the B4GALNT2 produced glycan and the results were compared to GTKO PAEC specific non-Gal antibody induction. Expression of porcine B4GALNT2 in pig cells and tissues was measured by qualitative and quantitative real time reverse transcriptase PCR and by Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) tissue staining.

Results

The porcine B4GALNT2 gene shares a conserved genomic organization and encodes an open reading frame with 76 and 70% amino acid identity to the human and murine B4GALNT2 genes, respectively. The B4GALNT2 gene is expressed in porcine endothelial cells and shows a broadly distributed expression pattern. Expression of porcine B4GALNT2 in human HEK cells (HEK-B4T) results in increased binding of antibody to the B4GALNT2 enzyme, and increased reactivity with anti-Sda and DBA. HEK-B4T cells show increased sensitivity to complement mediated lysis when challenged with serum from primates after pig to primate cardiac xenotransplantation. In GTKO and GTKO:CD55 cardiac xenotransplantation recipients there is a significant correlation between the induction of a non-Gal antibody, measured using GTKO PAECs, and the induction of antibodies which preferentially bind to HEK-B4T cells.

Conclusion

The functional isolation of the porcine B4GALNT2 gene from a PAEC expression library, the pattern of B4GALNT2 gene expression and its sensitization of HEK-B4T cells to antibody binding and complement mediated lysis indicates that the enzymatic activity of porcine B4GALNT2 produces a new immunogenic non-Gal glycan which contributes in part to the non-Gal immune response detected after pig-to-baboon cardiac xenotransplantation.

Keywords: antigen, B4GALNT2, cardiac xenotransplantation, immune response, porcine

Introduction

Carbohydrate modifications on glycoproteins and glycolipids are involved in a wide array of biological processes including protein stability, development, and cell growth. Variations in carbohydrate modification between individuals and between species define a form of immune self-recognition. Differences in expression of ABH blood group antigens between individuals has long been recognized as a prohibitive boundary across which blood transfusion and organ transplantation is generally not performed. Individuals which do not express a particular ABH antigen are stimulated by intestinal microflora to produce antibody to that glycan. This preformed antibody can induce a hemolytic reaction or promote hyperacute or accelerated allograft rejection of ABH incompatible grafts. The same process occurs across species. Humans and Old World primates do not produce oligosaccharides with terminal galactose α 1,3, galactose (αGal), whereas all other mammals synthesize terminal αGal glycans 1. As a consequence, humans make high levels of anti-Gal antibody. Anti-Gal antibody is a major immune barrier to xenotransplantation 2. This antibody has also been implicated in other clinical pathologies, notably the accelerated calcification of glutaraldehyde-fixed porcine bioprosthetic material and degeneration of bioprosthetic replacement heart valves 3,4.

Targeted genetic modification has been used to mutate the α-galactosyltransferase (GGTA-1) gene of the pig (GTKO) 5–7. This mutation eliminates the enzyme function and, when homozygous, blocks the synthesis of terminal αGal moieties on glycoproteins 8–11. Porcine GTKO tissue does not bind anti-Gal antibody and transplantation of GTKO cells, tissue and organs does not induce a specific anti-Gal antibody response. Elimination of this antigen has not eliminated GTKO xenograft rejection which remains a predominantly antibody-mediated process now directed to non-Gal antigens 12,13. We have used proteomic analysis of porcine aortic endothelial cell (PAEC) membranes and expression library screening of PAEC cDNA libraries to identify immunogenic non-Gal target antigens that may contribute to xenograft rejection 14,15. Using sera, obtained after pig-to-baboon cardiac xenotransplantation, these studies identified 43 potential non-Gal target antigens including six cDNAs, isolated from PAEC expression libraries. When expressed on human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK) these cDNAs each produce a porcine antigen that binds to baboon non-Gal IgG. A BLAST search identified one of these recovered cDNAs as a porcine glycosyltransferase with homology to a predicted Bos Taurus β1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (B4GALNT2) sequence 14. In humans and mice the B4GALNT2 gene catalyzes the terminal addition of N-acetylgalactosamine to a sialic acid modified lactosamine to produce GalNAc β1-4[Neu5Ac α2-3]Gal β1-4GlcNAc β1-3Gal, the Sda (Sid blood group, also known as CAD or CT) blood group antigen 16,17. In this study, we further characterize the porcine B4GALNT2 coding sequence, genomic organization, expression, and functional significance.

Materials and methods

Cells, culture conditions, and transfection methods

Porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAECs) were isolated from GTKO A- and O-type blood group pig aortas as previously described 18 and cultured in EGM media (Lonza Inc., Allendale, NJ, USA). Porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from GTKO pig blood by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll–Hypaque. Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK) and HEK cells expressing the porcine B4GALNT2 cDNA were grown in DMEM media with 10% FBS at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The full length pig B4GALNT2 open reading frame was amplified from the original library isolated clone using a primers set containing a Kozak consensus sequence and in-frame translation stop signals, respectively (Forward: 5′- ACCATGACTTCGTACAGCCCTAG-3′, Reverse: 5′- CAGATACCTTAGGTGGCACATTGGAG-3′). The PCR product was inserted into pcDNA3.1/V5-His TOPO expression vector (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and transfected into HEK cells using Lipofectamine-2000 (Life Technologies). A stable G418 resistant HEK clone expressing the porcine B4GALNT2 genes (HEK-B4T) was established and used for further real-time RT-PCR, immunohistochemical staining, complement dependent cytotoxicity, and flow cytometry analysis.

siRNA isolation and transfection

B4GALNT2 specific siRNA and control siRNA for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were generated from the coding region of each gene using a BLOCK-iT Dicer RNAi Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instruction. RNAi primers for B4GALNT2 were: Forward: 5′-ATGACTTCGTACAGCCCTAG-3′ and Reverse: 5′-CAGATACCTTAGGTGGCACATTGGAG-3′. RNAi primers for GAPDH were Forward: 5′-AGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAAC-3′ and Reverse: 5′-AGTGGTCGTTGAGGGCAATG-3′. The diced siRNA was purified through a RNA Spin Cartridge (Life Technologies). B4GALNT2 and GAPDH diced siRNAs were transfected into HEK-B4T cells using Lipofectamine-2000 (Life Technologies). After 48 h, total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA. USA). B4GALNT2 expression was monitored by real-time RT-PCR and immunohistochemical staining.

Real-time and qualitative RT-PCR analysis of B4GALNT2 expression

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen Inc.). Porcine tissue RNA was extracted using 1 g of frozen pig tissue homogenized in 10 ml cold STAT-60 RNA (Tel-Test Inc., Friendswood, TX, USA) and processed as recommended. For both qualitative and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

To survey the expression of porcine B4GALNT2 a gene specific one-step reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) assay using 0.5 μg of total tissue RNA and primers for pig B4GALNT2 (Forward: TACAGCCCTAGATGTCTGTC in exon 1, Reverse: CTCTCCTCTGAAAGTGTTCGAG in exon 3) was used to amplify a 334 bp product. Primers for beta-actin (Forward: CAAGATCATCGCGCCTCCA exon 6, Reverse: ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCT, exon 6) produce a 108 bp product which was used as a loading control. The authenticity of each amplified PCR product was confirmed by sequencing. Gene specific amplification was performed in a MyCycler Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using one-step RT-PCR reaction (USB-Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with reverse transcription performed at 50 °C for 30 min. Amplification conditions consisted of 95 °C for 10 min, and 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s. Amplification products were run in a 1.5% agarose gel.

For quantitative real-time analysis (Figs 3C and 4B) QuantiTect SYBR Green one-step RT-PCR was used (Qiagen Inc.) according to the manufacture's instruction. The cycling conditions were as follows: 50 °C for 30 min for reverse transcriptase, 95 °C for 15 min, and 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The B4GALNT2 primers for quantitative real time PCR (Fig. 3C) were: rt-Forward: 5′-GCGACTCCAAAGAATTGGCTTC-3′ (exon 10) and rt-Reverse 5′-TGGTGACCTATGATCACGTGTG-3′(exon 11) which produces a 120 bp RT-PCR product. A normalized dCT was calculated using β-actin expression and the relative change in B4GALNT2 expression, ddCT, was calculated based on B4GALNT2 expression in the absence of siRNA 19. Pig and PAEC AO blood group determination was performed as described 20.

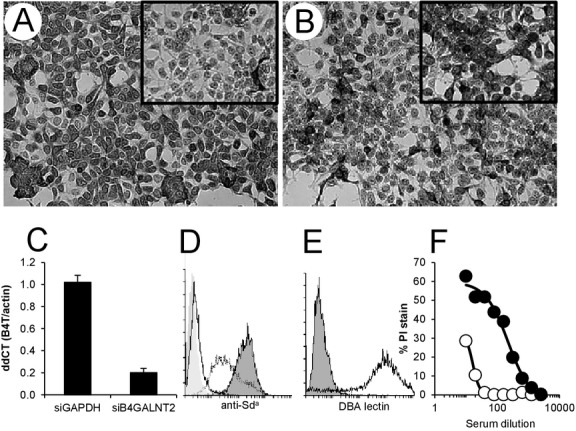

Figure 3.

Expression of B4GALNT2 protein and synthesis of the Sda antigen on HEK-B4T cells. (A) HEK-B4T cells show increased anti-human B4GALNT2 staining compared to HEK cells (insert). (B) Staining is dependent on porcine B4GALNT2 mRNA expression as HEK-B4T cells transfected with porcine B4GALNT2 siRNA show decreased staining compared to cell transfected with control GAPDH siRNA (insert in B). (C) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of B4GALNT2 RNA in HEK-B4T cells after transfection with control (siGAPDH) or porcine specific (siB4GALNT2) siRNA. Gene expression was normalized to pig beta-actin (dCT) and expressed as a ratio to B4GALNT2 expression in HEK-B4T cells without siRNA transfection (ddCT). Error bars are standard error of the mean. (D) Flow cytometry detection of anti-Sda antibody (KM694) binding to HEK (dotted line) and HEK-B4T cells (black line filled). Background is secondary antibody only binding to HEK cells (filled no line). KM694 binding to HUVECs (solid line no fill) is negative. (E) FITC conjugated Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) staining of HEK-B4T cells lines (black line) and control HEK cells (filled). (F) Complement-dependent cytotoxicity of HEK (open) and HEK-B4T (filled) cells challenged with primate serum after pig-to-primate xenotransplantation.

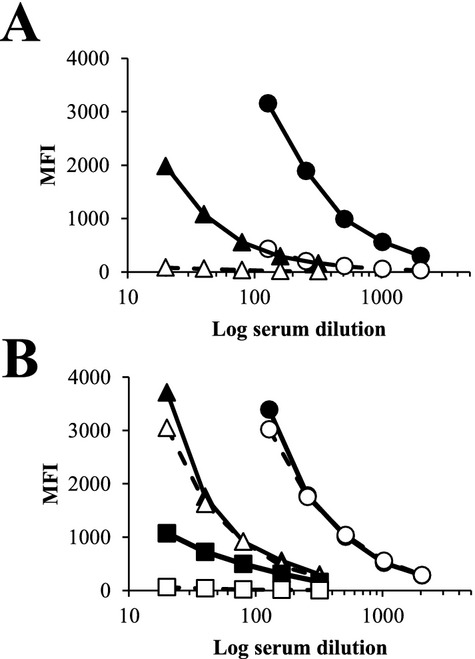

Figure 4.

Serum absorption of pig-to-baboon induced antibody to HEK-B4T (B4T) cells. Sensitized baboon serum was absorbed by incubating baboon serum (1 : 10 dilution) with 1 × 107 GTKO PAECs (A) or HUVECs (B) for 1 h at 4 °C. Absorption was performed 3 times for each cell type. IgG binding was analyzed by flow cytometry in dilutions from 1 : 20 to 20 : 48. (A) Closed symbols IgG binding from whole serum to GTKO PAECs (circle) and HEK-B4T cells (triangle). Open symbols are IgG binding after absorption with GTKO PAECs. Over the dilution range, absorption reduced IgG binding by an average of 89% for GTKO PAECs and 94% for HEK-B4T cells. (B) Closed symbols IgG binding from whole serum to GTKO PAECs (circle), HEK-B4T cells (triangle) and HUVEC (square). Open symbols are IgG binding after absorption with HUVECs. Absorption reduced HUVEC reactivity on average by 96%, had a minimal effect on IgG binding to GTKO PAECs (0.05%) and only a minor reduction of IgG binding to HEK-B4T (12%) cells.

Cell staining and flow cytometry

Fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (FITC-DBA; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) and an anti-Sda antibody KM694 (kindly provided by Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used to detect the glycan products of porcine B4GALNT2 expression in cultured human cells. Cells (2.5 × 105) in FACS buffer (phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 1% bovine serum albumin) were stained with 1 to 5 μg/ml KM694 or 10 μg/ml of FITC-DBA for 45 min at 4 °C. Cells stained with KM694 were washed in FACS buffer and subsequently stained with a FITC conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (2 μg/ml Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). All cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) cytometer and CellQuest software.

Immunohistochemical staining of HEK and HEK-B4T cells with rabbit anti-human B4GALNT2 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis., MO, USA) was used to assess B4GALNT2 protein expression after siRNA transfection. Cells were fixed in cold methanol, washed with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked with 10% non-immune serum. Cells were incubated with rabbit anti-human B4GALNT2 in FACS buffer (1 : 75 dilution) for 2 h and washed with PBS. Anti-B4GALNT2 binding was detected with an anti-rabbit diaminobenzidine kit (ZymedLife Technologies, Paisley, UK) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Induced antibody directed to the B4GALNT2 produced porcine glycan after pig-to-baboon heterotopic GTKO or GTKO:CD55 cardiac xenotransplantation was measured by comparing differential antibody binding to HEK and HEK-B4T cells. Cells (2.5 × 105) were stained with pretransplant, and post-explant serial serum dilutions (1 : 5 to 1 : 40) at 4 °C for 45 min in FACS buffer. After washing, bound antibody was detected using a phycoerythrin conjugated goat anti-human IgM or IgG secondary. Induction of antibody specific for the B4GALNT2 produced glycans was estimated as the ratio of induced antibody binding to HEK-B4T cells compared to HEK cells (anti-B4GALNT2 glycan = MFI post explant (HEK-B4T)/pretransplant (HEK-B4T): MFI post-explant (HEK)/pretransplant (HEK). Post-explant induction of non-Gal antibody was measured using GTKO PAECs as previously described using serum samples from earlier GTKO or GTKO:CD55 heterotopic cardiac transplants 11 or transplant recipients subject to similar immune suppression. The induced antibody binding data were used to calculate a Spearman rank correlation coefficient for IgM and IgG specific reactivity to HEK-B4T cells and GTKO PAECs. A two tailed non-directed P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. In Table2, the induced HEK-B4T antibody response is represented in a semi-quantitative scale with ratios <2 scored as negative, 2.0 to 2.5 + , 2.5 to 5.0 ++, 5.0 to 10.0 +++, and greater than 10 ++++.

Table 2.

Differential immune response to HEK-B4T cells after cardiac xenotransplantation

| Donor | Survival (days) | HEK-B4T IgM | HEK-B4T IgG | GTKO PAEC IgM | GTKO PAEC IgG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTKO:CD55 | 71 | − | + | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| GTKO:CD55 | 31 | − | − | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| GTKO:CD55 | 28 | +++ | +++ | 4.8 | 2.5 |

| GTKO:CD55 | 27 | +++ | + | 2.2 | 8.5 |

| GTKO | 22 | +++ | ++++ | 1.9 | 7.3 |

| GTKO | 21 | − | − | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| GTKO:CD55 | 18 | − | − | 0.4 | 0.4 |

Table shows the specific induced antibody response in pig-to-baboon heterotopic cardiac xenograft recipients directed to the B4GALNT2 (HEK-B4T) glycan or to GTKO PAECs. Antibody reactivity to HEK-B4T cells was estimated as described in the Materials and Methods. There was a positive and significant (P < 0.05) Spearman rank correlation coefficient between the anti-PAEC and anti-HEK-B4T IgM (r = 0.8929) and IgG (r = 0.8571) immune response.

Complement-mediated lysis

Human embryonic kidney and HEK-B4T cells (2 × 105) were incubated with a dilution of heat inactivated baboon serum at 4 °C for 45 min, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 20% fresh rabbit complement (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C for 1 h. Cell were stained with propidium iodide (3 μg/ml) placed on ice and analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and the average proportion of propidium iodide stained cells is reported. Baboon serum came from previously described pig to primate cardiac xenograft recipients 14,21. Serum heat inactivation was performed at 56 °C for 30 min using a temperature controlled water bath.

DBA lectin staining of pig tissues

Fresh pig tissues were embedded and snap frozen in optimal cutting temperature material (OCT. Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, IN, USA). Sections (8 μm) were cut, air dried, and acetone fixed prior to staining. Sections were cleared of OCT by washing in distilled water and PBS, blocked with FACS buffer and stained with FITC-DBA (4 μg/ml) in FACS buffer at 4 °C overnight, washed with PBS and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Stained sections were photographed using a Leica DMI4000B fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Results

Sequence analysis and genomic organization

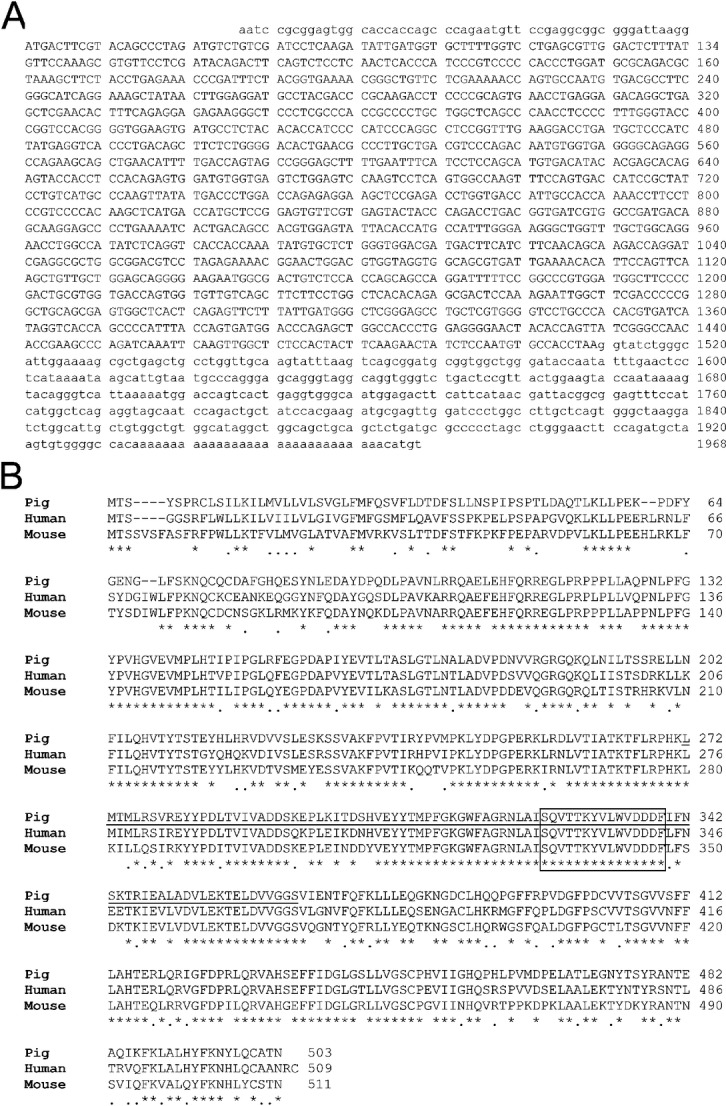

Expression screening of a porcine aortic endothelial cell (PAEC) library using IgG induced after pig-to-baboon cardiac xenotransplantation isolated a porcine cDNA with 54 base pairs of 5′ untranslated sequence, a 1509 base pair open reading frame and 459 bp of 3′ untranslated sequence including a putative polyadenylation sequence (Fig.1A, GenBank accession: KF501048). A BLAST search identified this cDNA as a porcine glycosyltransferase with homology to known or predicted β1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (B4GALNT2) products from several mammalian species including the human and mouse B4GALNT2 proteins. A comparison of these protein sequences shows the porcine open reading frame to have 76 and 70% amino acid identity to human and murine B4GALNT2 proteins, respectively (Fig.1B). In contrast amino acid identity to the related human and murine B4GALNT1 protein is <50% (data not shown). Analysis of the porcine protein sequence with the NCBI Conserved Domain Database 22 identified a putative GT-A type fold (underlined). This region includes a conserved structural motif (SQVTTKYVLWVDDDF), present in both human and murine B4GALNT2, which contains an acidic divalent cation binding site (DXD) commonly found in glycosyltransferases which use a UDP-sugar as the donor substrate 23.

Figure 1.

Sequence and homology comparison of porcine B4GALNT2. (A) Sequence of the porcine B4GALNT2 cDNA (GenBank: KF501048). Numbering begins with the start codon. Uppercase letters are the protein coding sequences, lower case letter are untranslated sequences. (B) Amino acid homology comparison between porcine, human and murine B4GALNT2 protein sequences. An asterisk indicates a shared amino acid identity, a line indicates a conserved amino acid substitution and a space indicates a non-conserved amino acid residue. The underlined region represents a conserved GT-A fold 22 and the boxed region highlights the conserved divalent cation binding domain 23.

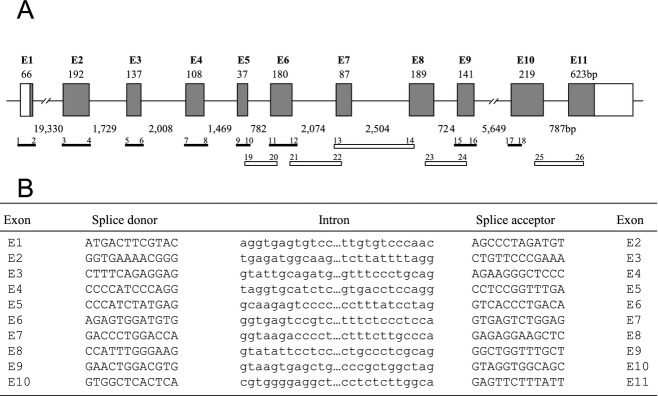

To map the genomic organization, the porcine B4GALNT2 cDNA was used to identify a porcine BAC clone obtained from the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute BACPAC Resource Centre (#AC173453). Based on the intron/exon structure of human and mouse B4GALNT2 and the porcine genomic sequences derived from the Sus scrofa working draft of AC173453.2, clone RP44-32E24, we generated a series of primers (Table1) to confirm the intron exon structure of the porcine B4GALNT2 gene (Fig.2A). These primers amplified exons 1 to 11, including variable lengths of neighboring intron sequence, and amplified introns 5 to 8 and 10. All PCR products were sequenced and compared to the original B4GALNT2 cDNA to identify intron-exon junction sequences (Fig.2B). The cDNA coding region is composed of 11 exons spread across approximately 40 000 base pairs. Exon 1 contains translation initiation start site and 5′ untranslated sequences. We have not directly mapped the transcriptional start site of the gene so there may be additional 5′ untranslated sequence or an upstream exon(s) not depicted in this figure. During the course of this study, a sequence for porcine B4GALNT2 99% identical to the clone we reported was added to the database (NM_001244330).

Table 1.

Primers for mapping the porcine B4GALNT2 genomic structure

| No. | ID | Sequence | BP to exon | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exon1-F | AAGGCAGGACCTAGAAGGTG | 90 | flank exon 1 |

| 2 | Exon1-R | AACGAGCAGGAACTCTCAAC | 185 | flank exon 1 |

| 3 | Exon2-F | GCTGTGCAAAAGCTTGTCAGTTTGC | 186 | flank exon 2 |

| 4 | Exon2-R | CACAGTAAAGCCACAGGAGGAG | 41 | flank exon 2 |

| 5 | Exon3-F | CCCAATCTGTGATCTTTGAC | 24 | flank exon 3 |

| 6 | Exon3-R | GGAATGAGTAGAGAGCTTCC | 41 | flank exon 3 |

| 7 | Exon4-F | ATCTGGCATGGTCAGTGCATTG | 145 | flank exon 4 |

| 8 | Exon4-R | CAGTGGTGGAAACAGTGAG | 150 | flank exon 4 |

| 9 | Exon5-F | AACTCTTGGCATCCTCTC | 51 | flank exon 5 |

| 10 | Exon5-R | TGAGACCAGCCACCATCTCA | 73 | flank exon 5 |

| 11 | Exon7-F | AGTGACCCAGATACCGTG | 29 | flank exon 6 |

| 12 | Exon7-R | CTAAGGATCCAGTGTTGTCAC | 224 | flank exon 6 |

| 13 | Exon8-F | TCCACAAACACTCGAGACAG | 84 | flank exon 7 |

| 14 | Exon8-R | TGGGTAGTACTCACGAACACTC | n/a | in exon 8 |

| 15 | Exon9-F | AGAGAGTCCCTCTCCTTCTTC | 152 | flank exon 9 |

| 16 | Exon9-R | TCAGATGGCAATGGGGTAGAAC | 22 | flank exon 9 |

| 17 | Exon10-F | ACAGGCTCCTTGGATATGGAG | 36 | flank exon 10 |

| 18 | Exon10-R | TTGACAACACCACTGGTCACCAC | n/a | in exon 10 |

| 19 | Intron5-F | GTTTGAAGGACCTGATGCTC | n/a | in exon 5 |

| 20 | Intron5-R | TGTTCAGTGTCCCCAGAGAAG | n/a | in exon 6 |

| 21 | Intron6-F | ACACGAGCACAGAGTACCACC | n/a | in exon 6 |

| 22 | Intron6-R | AAACTTGGCCACTGAGGACTTG | n/a | in exon 7 |

| 23 | Intron8-F | GACAGCCACGTGGAGTATTAC | n/a | in exon 8 |

| 24 | Intron8-R | TGAGATATGGCCAGGTTTCTG | n/a | in exon 9 |

| 25 | Intron10-F | GCGACTCCAAAGAATTGGCTTC | n/a | in exon 10 |

| 26 | Intron10-R | TGGTGACCTATGATCACGTGTG | n/a | in exon 11 |

The table list the names, sequences, and location of primers used to confirm the genomic organization of the porcine B4GALNT2 gene. Primer numbers (No.) correspond to values in Fig.2A. Not applicable, n/a.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the intron-exon organization (A) and splice junction sequences (B) of the porcine B4GALNT2 gene. (A) Shaded boxes represent exon coding sequences numbered E1–E11. Open boxes correspond to untranslated sequences present in the cDNA. The size of each exon is indicated in base pairs above each box and the intron distances are indicated below between each exon. The primer pairs (1–26, see Table1) and amplified products used to analyze the genomic structure from a BAC clone are illustrated below the genomic structure as solid bars for products covering exon/intron boundaries and open bars for products spanning entire introns. The primer numbering corresponds to the primers listed in Table1. (B) The proximal splice donor and distal splice acceptor nucleotide sequences (upper case) for each exon are shown. Adjacent intervening intron sequences (lower case) are shown. Exon numbering corresponds to (A).

Expression of porcine B4GALNT2 in human HEK cells

A stable G418 resistant HEK cell line expressing the porcine B4GALNT2 cDNA (HEK-B4T) was produced. This cell line bound higher levels of rabbit anti-human B4GALNT2 antibody (Fig.3A) compared with control HEK cells. The increased antibody binding was specific for expression of porcine B4GALNT2 mRNA as HEK-B4T cells transfected with siRNA to porcine B4GALNT2 exhibit an 80% decrease in porcine B4GALNT2 mRNA expression and a proportionate reduction in anti-human B4GALNT2 antibody binding (Fig.3B,C). No change in anti-B4GALNT2 staining or expression of B4GALNT2 mRNA was evident when cells were transfected with siRNA for GAPDH.

The human and mouse B4GALNT2 gene produces GalNAc β1-4[Neu5Ac α2-3]Gal β1-4GlcNAc β1-3Gal, the Sda blood group glycan, by the addition of a β1,4 N-acetyl galactosamine to a sialic acid modified lactosamine acceptor. HEK cells, but not HUVECs, bind a low level of anti-Sda hybridoma KM694 (Fig.3D). The HEK-B4T cell line shows increased binding of KM694 consistent with increased synthesis of the Sda antigen as a result of expression of porcine B4GALNT2. The Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) binds alpha linked terminal GalNAc structures 24, but also binds beta GalNAc residues as presented in the Sda glycan. The DBA lectin has been used to isolate the Sda pentasaccharide from murine small intestine 25, shows differential binding to humans Sda+ and Sda− glycoproteins 26, and is commonly used to detect the Sda antigen on cells and in tissue sections 17,27,28. HEK-B4T cells bind high levels of DBA and are strongly agglutinated by this lectin (Fig.3E). Expression of porcine B4GALNT2 in HEK-B4T cells increases cell sensitivity to complement mediated cytotoxicity (Fig.3F). HEK-B4T cells show a 20-fold enhancement of antibody-dependent complement-mediated lysis compared to HEK cells when challenged with pig-to-baboon cardiac xenotransplantation sensitized recipient serum.

Immunogenicity of B4GALNT2 produced antigens

Heterotopic GTKO or GTKO:CD55 cardiac xenograft recipients show variable induction of IgG and IgM binding to GTKO PAECs (Table2). Comparing pretransplant and post explant serum (obtained from immune suppressed recipients 1 to 3 weeks after organ recovery) three recipients (survival 28, 27, and 22 days) showed a clear 2- to 8-fold increase in non-Gal antibody and four recipients (survival 71, 31, 21, and 18 days) showed a minimal non-Gal antibody response. We used differential antibody binding to HEK-B4T and HEK cells to determine if this induced non-Gal antibody response included antibody reactivity specific to the glycans expressed on the HEK-B4T cell surface. The induction of specific post transplant IgM (r = 0.8929) and IgG (r = 0.8571) reactivity to HEK-B4T cells was significantly correlated with the induced non-Gal antibody response to GTKO PAECs (Table2). Recipients with a clear induced antibody response to GTKO PAECs also showed increased antibody reactivity for HEK-B4T cells. The antibody (IgG) reactivity to HEK-B4T cells in sensitized baboon serum can be blocked by immune absorption with GTKO PAECs (Fig.4A) but is unaffected by immune absorption using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Fig.4B). This suggests that the induced xenoreactive antibody response in baboons includes antibody directed to glycan antigens present on both HEK-B4T and GTKO PAECs, but not present on HUVECs which are negative for B4GALNT2 expression and the Sda antigen (Fig.3D).

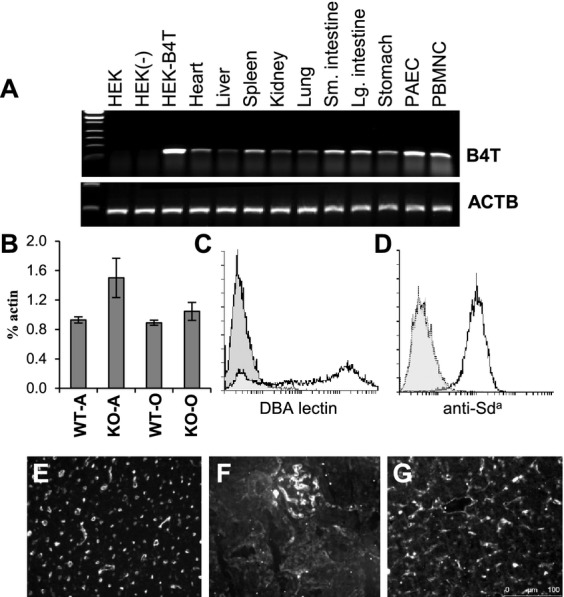

Expression of B4GALNT2 in porcine tissue

A panel of pig tissues was assessed for B4GALNT2 expression by qualitative RT-PCR. Expression of B4GALNT2 RNA was evident in cultured PAECs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells and at variable levels in most GT+ porcine tissues (Fig.5A). Expression of B4GALNT2 RNA was not strongly affected by the GGTA-1 Gal genotype as heterozygous (GGTA-1+/−) and GTKO pig tissues exhibited a similar pattern of B4GALNT2 expression (data not shown). Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis of B4GALNT2 gene expression in cultured GT+ and GTKO PAECs of the A- and O-type blood groups showed only moderate variation in B4GALNT2 expression (Fig.5B). Expression of porcine B4GALNT2 in HEK-B4T cells resulted in increased DBA and KM694 antibody binding in HEK-B4T cells (Fig.3D,E), however, PAECs show only strong DBA agglutination (Fig.5C) and do not stain with the anti-Sda antibody KM694 (Fig.5D). DBA staining of GTKO pig tissues (O-type blood group) was observed in vascular endothelial cells of the heart, in glomeruli and larger blood vessels in the kidney and by the reticuloendothelial cells of the liver (Fig.5E–G).

Figure 5.

Porcine B4GALNT2 gene expression. (A) Qualitative RT-PCR analysis of porcine B4GALNT2 RNA expression in cell lines and pig tissues. The top panel represents specific expression of B4GALNT2 (B4T) and the bottom panel shows expression of porcine actin (ACTB). Samples; Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK), HEK cells transformed with an unrelated porcine cDNA (HEK-), HEK cells expressing porcine B4GALNT2 (HEK-B4T), porcine tissue samples (heart, liver, spleen, kidney, lung, stomach, and small [Sm] and large [Lg] intestine), porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAEC) and porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). (B) Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis of porcine B4GALNT2 gene expression in Gal-positive wild type (WT) and Gal-negative (KO) endothelial cells. On the x-axis the A- and O-type blood group is indicated for each Gal genotype. B4GALNT2 expression is plotted as the average percentage of βactin expression. Error bars are the standard deviation. (C) Positive FITC-DBA staining (bold line) of O-type PAECs. Background (filled) staining with FITC conjugated Solanum tuberosum agglutinin which does not bind to PAECs. (D) Negative staining of O-type PAECs with KM694 (dotted line). Background (filled) is FITC conjugated anti-mouse IgM only staining of PAECs. Positive stain (solid line) is HEK-B4T stained with KM694. (E–G) FITC conjugated DBA lectin staining of O-type GTKO pig heart (E), kidney (F) and liver (G).

Discussion

The porcine B4GALNT2 cDNA was originally isolated during a flow cytometry based library screen to identify human HEK cells expressing porcine cDNAs which encoded surface membrane antigens that bound to sensitized primate IgG after GT+ or GTKO pig cardiac xenotransplantation 14. The porcine cDNA and its encoded protein show the highest homology to the B4GALNT2 gene with 76 and 70% amino acid identity with the human and mouse gene, respectively (Fig.1). We show that the porcine gene also shares with human and mouse a conserved intron/exon genomic organization (Fig.2). Consistent with a conserved protein sequence a stable HEK cell line expressing the porcine cDNA (HEK-B4T) binds increased levels of rabbit anti-human B4GALNT2 antisera and, using siRNA inhibition, we show this binding is dependent on expression of the porcine cDNA (Fig.3B,C). Expression of the porcine cDNA in HEK-B4T cells also results in increased binding of anti-Sda antibody and DBA lectin. On this structural and functional data, we conclude that the isolated porcine cDNA encodes the porcine B4GALNT2 gene.

Porcine B4GALNT2 enzymatic activity has been reported from swine large intestine mucosal cells 29 and immunostaining of the Sda antigen has been detected in porcine primordial germ cells 30. To our knowledge, this is the first molecular analysis of porcine B4GALNT2 gene expression in pig tissues. In the pig, we find B4GALNT2 mRNA expression in PAECs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and across a wide array of tissues (Fig.5A). This porcine B4GALNT2 gene expression pattern is in distinct contrast to humans and most strains of mice where B4GALNT2 expression and the Sda antigen, generally detected by lectin staining, is largely restricted to gastrointestinal, skin and renal tissues and is notably absent from arteries, heart and skeletal muscle 23,27,31,32. Vascular expression of B4GALNT2 is not unprecedented however as mice which carry the modifier of von Willebrand factor-1 (Mvwf1) mutation exhibit a shift from gastrointestinal epithelial cell expression to vascular endothelial cell expression of B4GALNT2 27.

The B4GALNT2 cDNA was originally isolated by screening an expression library with post transplant IgG from pig-to-baboon cardiac heterotopic xenotransplantation recipients transplanted without T-cell immune suppression 14,21. In these recipients, the non-Gal immune response was especially strong and five of five transplant recipients showed an induced immune response with preferential binding to HEK-B4T cells 14. In this study, we extend our previous results and show in recipients subject to substantial immune suppression that there is a correlation between an induced non-Gal antibody response and the induction of antibody with preferential binding to HEK-B4T cells (Table2). We further show that expression of the porcine B4GALNT2 gene in HEK-B4T cells produced a 20-fold enhancement to complement mediated lysis (Fig.3F). These results and the pattern of B4GALNT2 gene expression strongly indicate that the porcine B4GALNT2 enzyme produces an immunogenic non-Gal glycan on endothelial cells which contributes in part to the non-Gal immune response after pig-to-baboon cardiac xenotransplantation.

The precise structure of the glycan(s) produced on pig endothelial cells by the B4GALNT2 enzyme remains under investigation. Classically in humans and mice expression of B4GALNT2 produces the Sda antigen. Consistent with this we detect increased expression of the Sda antigen, based on KM694 antibody and DBA lectin binding, in HEK-B4T cells but surprisingly do not observe anti-Sda KM694 antibody binding to PAECs. It is unclear why this is the case. Ongoing glycan profiling of HEK and HEK-B4T cells suggests that the porcine B4GALNT2 enzyme may produce a wider variety of GalNAc glycans in HEK-B4T cells then normally attributed to the human of mouse enzyme (data not shown). Alternatively KM694 binding may be affected by the presentation of the Sda epitope on pig cells, possibly due to inclusion of N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5GC) in the structure. In any case, our absorption experiments (Fig.4) show that GTKO PAECs and HEK-B4T cells share B4GALNT2 dependent antigens which are not present on HUVECs. Interestingly, an induced antibody response in baboons to trace acidic cardiac glycolipids has been reported 8. Whether this antibody response is related to the glycan produced by B4GALNT2 remains to be determined.

There are a limited set of potential antibody and glycan antigen combinations which may be involved in xenogeneic antibody dependent inflammatory processes. Antibody to the Gal antigen is the dominant xenoreactivity in both humans and Old World non-human primates 1. Anti-Gal antibodies are known to be sufficient to induce organ rejection of Gal-positive vascular grafts 33–35 and to accelerate calcification of fixed bioprosthetic animal tissue 3,36. Humans, but not nonhuman primates, also make a complex array of antibody to a common mammalian sialic acid modification Neu5GC 37. This antibody reactivity is widely expected to contribute to xenograft rejection in humans 38–41 but its significance remains uncertain due to the absence of anti-Neu5GC antibody in experimental non-human primate models. Screening strategies based on panels of defined oligosaccharides have failed to detect xenogeneic sensitization to other common oligosaccharides (Forssman antigen and α- and β-lactosamine) 42,43. The results presented in this study indicate that porcine B4GALNT2 produces an immunogenic non-Gal glycan which contributes to the induced non-Gal antibody response in the pig-to-baboon xenotransplant model. It remains to be determined if antibody to this glycan contributes to xenograft rejection. Additionally, while most humans express low levels of anti-Sda antibody which agglutinates rare human red blood cells with high levels of Sda antigen (CAD or super Sda) 17, whether an anti-Sda immune response will occur in humans exposed to porcine tissues and the relationship between human anti-Sda antibody and the immune response in observed baboons remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical help contributed by Karen Schumacher for writing this manuscript. This research was funded by an Immunobiology of Xenotransplantation cooperative research grant (AI066310) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease at the National Institute of Health, by Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre funds from the National Institute of Health Research, and supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- B4GALNT2

β1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase

- BLAST

Basic local alignment search tool

- DBA

Dolichos biflorus agglutinin

- Gal

galactose α 1,3, galactose

- GalNAc

N-acetylgalactosamine

- GTKO

pigs with a GGTA-1 α-galactosyltransferase mutation

- HEK

human embryonic kidney cells

- HEK-B4T

HEK cells expressing the porcine B4GALNT2 gene

- HUVEC

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- Mvwf-1

modifier of von Willebrand factor-1 mutation

- Neu5GC

N-acetylneuraminic acid

- PAEC

porcine aortic endothelial cell

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase dependent polymerase chain reaction

- Sda

The SID blood group expressing a GalNAc β1-4[Neu5Ac α2-3]Gal β1-4GlcNAc β1-3Gal terminal glycan

Author contribution

Guerard W. Byrne: Dr. Byrne contributed to the concept and design of the research, data acquisition, analysis and insight in interpreting the results. He was responsible for drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, contributed to securing funding, and gave final approval for the article.

Zeji Du: Dr. Du was responsible for data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the results. He contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and gave final approval.

Paul Stalboeger: Mr. Stalboeger was responsible for data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the results. He contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and gave final approval.

Heide Kogelberg: Dr. Kogelberg was responsible for data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the results. She contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and gave final approval.

Christopher G. A. McGregor: Dr. McGregor contributed to the concept and design of the research, was primarily responsible for securing funding to support this work, provided critical review and final approval of the article.

References

- 1.Galili U, Shohet SB, Kobrin E, et al. Man, apes, and old world monkeys differ from other mammals in the expression of alpha-Galactosyl epitopes on nucleated cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17755–17762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne GW, McGregor CG. Cardiac xenotransplantation: progress and challenges. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17:148–154. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283509120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGregor CG, Carpentier A, Lila N, et al. Cardiac xenotransplantation technology provides materials for improved bioprosthetic heart valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manji RA, Menkis AH, Ekser B, Cooper DK. Porcine bioprosthetic heart valves: the next generation. Am Heart J. 2012;164:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelps CJ, Koike C, Vaught TD, et al. Production of alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science. 2003;299:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1078942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai L, Kolber-Simonds D, Park K-W, et al. Production of α-1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pigs by nuclear transfer cloning. Science. 2002;295:1089–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1068228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma A, Naziruddin B, Cui C, et al. Pig cells that lack the gene for alpha1-3 galactosyltransferase express low levels of the gal antigen. Transplantation. 2003;75:430–436. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000053615.98201.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diswall M, Angstrom J, Karlsson H, et al. Structural characterization of alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pig heart and kidney glycolipids and their reactivity with human and baboon antibodies. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17:48–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diswall M, Angstrom J, Schuurman HJ, et al. Studies on glycolipid antigens in small intestine and pancreas from alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout miniature swine. Transplantation. 2007;84:1348–1356. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000287599.46165.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nottle MB, Beebe LF, Harrison SJ, et al. Production of homozygous alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pigs by breeding and somatic cell nuclear transfer. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14:339–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGregor CG, Ricci D, Miyagi N, et al. Human CD55 expression blocks hyperacute rejection and restricts complement activation in Gal knockout cardiac xenografts. Transplantation. 2012;93:686–692. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182472850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu A, Hisashi Y, Kuwaki K, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with humoral rejection of cardiac xenografts from alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs in baboons. Am J Path. 2008;172:1471–1481. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tazelaar HD, Byrne GW, McGregor CG. Comparison of Gal and non-Gal-mediated cardiac xenograft rejection. Transplantation. 2011;91:968–975. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318212c7fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne GW, Stalboerger PG, Du Z, et al. Identification of new carbohydrate and membrane protein antigens in cardiac xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:287–292. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318203c27d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrne GW, Stalboerger PG, Davila E, et al. Proteomic identification of non-Gal antibody targets after pig-to-primate cardiac xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:268–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renton PH, Howell P, Ikin EW, Giles CM, Goldsmith KLG. Anti-Sda, a New Blood Group Antibody. Vox Sang. 1967;13:493–501. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bird GW, Wingham J. Cad(super Sda) in a British family with eastern connections: a note on the specificity of the Dolichos biflorus lectin. J Immunogenet. 1976;3:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313x.1976.tb00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrne GW, McCurry KR, Martin MJ, et al. Transgenic pigs expressing human CD59 and decay-accelerating factor produce an intrinsic barrier to complement-mediated damage. Transplantation. 1997;63:149–155. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199701150-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto F, Yamamoto M. Molecular genetic basis of porcine histo-blood group AO system. Blood. 2001;97:3308–3310. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davila E, Byrne GW, Labreche PT, et al. T-cell responses during pig-to-primate xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2005.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchler-Bauer A, Panchenko AR, Shoemaker BA, et al. CDD: a database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:281–283. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montiel MD, Krzewinski-Recchi MA, Delannoy P, Harduin-Lepers A. Molecular cloning, gene organization and expression of the human UDP-GalNAc:Neu5Acalpha2-3Galbeta-R beta1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase responsible for the biosynthesis of the blood group Sda/Cad antigen: evidence for an unusual extended cytoplasmic domain. Biochem J. 2003;373:369–379. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piller V, Piller F, Cartron JP. Comparison of the carbohydrate-binding specificities of seven N-acetyl-D-galactosamine-recognizing lectins. Eur J Biochem. 1990;191:461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamada Y, Muramatsu H, Arita Y, et al. Structural studies on a binding site for Dolichos biflorus agglutinin in the small intestine of the mouse. J Biochem. 1991;109:178–183. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu AM, Wu JH, Watkins WM, et al. Differential binding of human blood group Sd(a+) and Sd(a-) Tamm-Horsfall glycoproteins with Dolichos biflorus and Vicia villosa-B4 agglutinins. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:323–326. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00617-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohlke KL, Purkayastha AA, Westrick RJ, et al. Mvwf, a dominate modifier of murine von Willebrand factor, results from altered lineage-specific expression of a glycosyltransferase. Cell. 1999;96:111–120. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnsen JM, Levy GG, Westrick RJ, et al. The endothelial-specific regulatory mutation, Mvwf1, is a common mouse founder allele. Mamm Genome. 2008;19:32–40. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malagolini N, Dall'Olio F, Guerrini S, Serafini-Cessi F. Identification and characterization of the Sda beta 1,4,N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase from pig large intestine. Glycoconj J. 1994;11:89–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00731148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klisch K, Contreras DA, Sun X, et al. The Sda/GM2-glycan is a carbohydrate marker of porcine primordial germ cells and of a subpopulation of spermatogonia in cattle, pigs, horses and llama. Reproduction. 2011;142:667–674. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ponder BA, Wilkinson MM. Organ-related differences in binding of Dolichos biflorus agglutinin to vascular endothelium. Dev Biol. 1983;96:535–541. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin D, Zeng H, Ma L, et al. Cutting Edge: NK cells mediate IgG1-dependent hyperacute rejection of xenografts. J Immunol. 2004;172:7235–7238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gock H, Salvaris E, Murray-Segal L, et al. Hyperacute rejection of vascularized heart transplants in BALB/c Gal knockout mice. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:237–246. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon PM, Neethling FA, Taniguchi S, et al. Intravenous infusion of Galα1-3Gal oligosaccharides in baboons delays hyperacute rejection of porcine heart xenografts. Transplantation. 1998;65:346–353. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199802150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lila N, McGregor CG, Carpentier S, et al. Gal knockout pig pericardium: new source of material for heart valve bioprostheses. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Padler-Karavani V, Yu H, Cao H, et al. Diversity in specificity, abundance, and composition of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in normal humans: potential implications for disease. Glycobiology. 2008;18:818–830. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Padler-Karavani V, Varki A. Potential impact of the non-human sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid on transplant rejection risk. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2011.00622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tahara H, Ide K, Basnet NB, et al. Immunological property of antibodies against N-glycolylneuraminic acid epitopes in cytidine monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:3269–3275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saethre M, Baumann BC, Fung M, et al. Characterization of natural human anti-non-gal antibodies and their effect on activation of porcine gal-deficient endothelial cells. Transplantation. 2007;84:244–250. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000268815.90675.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lutz AJ, Li P, Estrada JL, et al. Double knockout pigs deficient in N-glycolylneuraminic acid and galactose alpha-1,3-galactose reduce the humoral barrier to xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20:27–35. doi: 10.1111/xen.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeh P, Ezzelarab M, Bovin N, et al. Investigation of potential carbohydrate antigen targets for human and baboon antibodies. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blixt O, Kumagai-Braesch M, Tibell A, et al. Anticarbohydrate antibody repertoires in patients transplanted with fetal pig islets revealed by glycan arrays. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:83–90. [Google Scholar]