Abstract

Chemokines have been implicated as key contributors of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) metastasis. However, the role of CXCR7, a recently discovered receptor for CXCL12 ligand, in the pathogenesis of NSCLC is unknown. To define the relative contribution of chemokine receptors to migration and metastasis we generated human lung A549 and H157 cell lines with stable knockdown of CXCR4, CXCR7, or both. Cancer cells exhibited chemotaxis to CXCL12 that was enhanced under hypoxic conditions, associated with a parallel induction of CXCR4, but not CXCR7. Interestingly, neither knockdown cell line differed in the rate of proliferation, apoptosis or cell adherence; however, in both cell lines, CXCL12-induced migration was abolished when CXCR4 signaling was abrogated. In contrast, inhibition of CXCR7 signaling did not alter cellular migration to CXCL12. In an in vivo heterotropic xenograft model using A549 cells, expression of CXCR4, but not CXCR7, on cancer cells was necessary for the development of metastases. In addition, cancer cells knocked-down for CXCR4 (or both CXCR4 and CXCR7) produced larger and more vascular tumors as compared to wild-type or CXCR7 knock-down tumors, an effect that was attributable to cancer cell-derived CXCR4 out competing endothelial cells for available CXCL12 in the tumor microenvironment. These results indicate that CXCR4, not CXCR7, expression engages CXCL12 to mediate NSCLC metastatic behavior.

Keywords: bronchogenic carcinoma, CXCL12, angiogenesis, chemotaxis, A549, H157

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and is the leading cause of cancer death (1, 2). Most patients with NSCLC die of metastatic disease, typically involving the mediastinal lymph nodes, other areas of the lungs, adrenal glands, brain, liver and the bone marrow. Understanding the biology that underlies NSCLC metastasis formation is therefore important.

The CXCL12-CXCR4 biological axis is an evolutionarily preserved mechanism essential to homing of progenitor cells during organogenesis, retention of precursor cells in the bone marrow, and their recruitment to sites of tissue repair. In addition to its physiologic roles, this pathway has been implicated in metastasis formation in diverse cancers: many human cancer cells, including NSCLC squamous cell and adenocarcinoma, express CXCR4. In addition, the expression of CXCR4 on cancer cells is upregulated in hypoxia, as might be encountered in the tumor microenvironment (3, 4). CXCL12 is constitutively expressed in tissues that are targets of metastases, and a substantial body of literature supports the notion that interrupting this ligand-receptor interaction inhibits cancer cell migration and metastasis formation (5, 6). CXCR4 and CXCL12 were thought to be an exclusive ligand-receptor pair until the discovery of CXCR7, an alternative receptor for CXCL12 that also binds CXCL11 (7). CXCR7 is expressed on subsets of T and B cells, activated endothelial cells, fetal hepatocytes, as well as many cancer cells (6). In the context of malignancy, the role of CXCR7 and its functional relationship to CXCR4, CXCL12 and CXCL11 are incompletely defined: in diverse experimental settings and using different cancer models, some studies have reported that CXCR7 acts exclusively as a decoy receptor (8), others report that it mediates migration to CXCL12 or CXCL11 (9–11), and still others indicating that it mediates cancer proliferation, apoptosis or adhesion (12–15), or angiogenesis (15, 16).

We sought to define the relative contribution of CXCR4 and CXCR7 in NSCLC migration in vitro and metastasis formation in vivo by generating human A549 and H157 cell lines that are stably knocked-down for CXCR4, CXCR7, or both. We report that migration and metastasis of NSCLC cells is dependent on the interaction of CXCL12 with CXCR4, but is independent of the interaction of CXCL11 or CXCL12 with CXCR7.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

A549 and H157 cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1 mM L-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, 1X Pen/Strep, and 10% fetal bovine serum, hereafter referred to as RPMI complete media. In some experiments, cells were transferred to RPMI with 1% fetal bovine serum (hereafter referred to as starvation media) and incubated in modular incubator chambers (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA) under normoxic (21% O2, 74% N2, 5% CO2) or hypoxic (1% O2, 94% N2, 5% CO2) culture conditions. In some experiments, 10 μg/ml anti-human CXCR4 (MAB170, R&D systems) or CXCR7 polyclonal antibodies (see below) were added to the media. Parental cell lines were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) at the beginning of the project. At the conclusion of the experiments, all parental and modified cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat DNA profiling and comparison to published ATCC profiles (Genetica, Burlington, NC).

Reagents

Polyclonal rabbit anti-human CXCR7 was produced by the immunization of a rabbit with a 21-mer peptide (MDLHLFDYAEPGNFSDISWPC) constituting the amino terminus of human CXCR7 (hCXCR7). The rabbit was immunized in multiple intradermal sites with CFA followed by three boosts in IFA. Direct ELISA was used to evaluate antisera titers, and serum was used for Western blot, and neutralization assays when titers had reached greater than 1:1,000,000. The specificity of anti-hCXCR7 Ab was assessed by Western blot analysis against cells expressing hCXCR7 and a panel of other human and murine recombinant cytokines. Polyclonal goat anti-human CXCL12 antibodies were produced as previously described (17).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with anti-hCXCR4 or anti-hCXCR7 antibodies or appropriate controls followed by APC-conjugated secondary antibodies (A-21463, BD Bioscience). In some experiments, cells were also stained with CD45-PerCP (557513, BD Bioscience) and rabbit anti-Factor VIII related antigen or appropriate control (F3520 and I-8140, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), followed by secondary AlexaFluor 610-R-phycoerythin goat anti-rabbit IgG (A20981, Invitrogen). To quantify metastases, organs were digested as previously described (3, 18–20). Organs from animals inoculated with GFP-transfected cancer cells were compared to organs from healthy animals, and the proportions of GFP-expressing cells in organ digests were quantified. Samples were analyzed on a FACS Canto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using FACS Diva software.

Establishment of stable knock-downs of CXCR4, CXCR7, and both CXCR4 and CXCR7 in A549 and H157 NSCLC cell lines

Green fluorescence protein (GFP) was transfected into parental A549 and H157 cell lines using EmGFP vector (K493600, Invitrogen). GFP-transfected cell lines had comparable migratory capacity to CXCL12 as compared to control cells that were not transfected with the vector. Block-iT Pol II miR RNAi Expression Vector Kit (K494300, Invitrogen) was used to generate knock-down cells. For CXCR4 knock-down cells, human CXCR4 miRNA oligo was designed (Top strand, 5′-TGC TGT TGA CTG TGT AGA TGA CAT GGG TTT TGG CCA CTG ACT GAC CCA TGT CAT ACA CAG TCA A-3′; Bottom strand, 5′-CCT GTT GAC TGT GTA TGA CAT GGG TCA GTC AGT GGC CAA AAC CCA TGT CAT CTA CAC AGT CAA C-3′) using Invitrogen miRNA Designer software. These two RNAi oligos were annealed (20 μM condition, 95 °C for 4 min) followed by ligation into pcDNA 6.2-GW/miR vector. Ligated product was transformed into TOP10 competent E. coli. Spectinomycin (50 μg/ml)-selected transformant was grown in LB media to purify CXCR4 miRNA-containing pcDNA 6.2-GW/miR (pcDNA 6.2-GW/CXCR4) vector. Purified pcDNA 6.2-GW/CXCR4 vector was mixed with pDONR 221 vector and pLenti6/V5-DEST vector to generate pLenti6/V5-GW/CXCR4 expression construct. Lentiviral stock, containing the packaged pLenti6/V5-GW/CXCR4 expression construct, was produced by co-transfecting the ViraPower Packaging Mix and pLenti6/V5-GW/CXCR4 expression construct into 293FT Producer cell line. Transduction of this lentiviral construct into A549 and H157 cell line was performed in the presence of polybrene, followed by selection with blasticidin. For CXCR7 knock down cells, CXCR7 miRNA oligo was designed (Top strand, 5′-TGC TGA AGA TGA GGT GTG TGA CTT TGG TTT TGG CCA CTG ACT GAC CAA AGT CAC ACC TCA TCT T-3′; Bottom strand, 5′-CCT GAA GAT GAG GTG TGA CTT TGG TCA GTC AGT GGC CAA AAC CAA AGT CAC ACA CCT CAT CTT C-3′) and processed for lentiviral transduction as described above. To produce cell lines with knockdown of both CXCR4 and CXCR7, CXCR4-knockdown cells were further transfected with CXCR7 miRNA followed by selection by RT-PCR. The resulting knock-down cell lines had greatly diminished expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7 mRNA and protein as compared to non-transfected parental cell lines (Supplemental Figure 1A–D). On flow cytometry, both A549 and H157 cell lines displayed cell surface expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7. CXCR4 expression was enhanced under hypoxic conditions as previously reported (3) whereas CXCR7 expression was unaffected. In both A549 and H157 CXCR4 knockdown lines, cell surface expression of CXCR4 was abolished without detectable effect on CXCR7 under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions; similarly, A549 and H157 CXCR7 knock-down lines had little detectable cell surface expression of CXCR7 but intact CXCR4 expression. A549 and H157 lines with both CXCR4 and CXCR7 knockdown had little detectable cell surface expression of either molecule under normoxic and hypoxic culture conditions (Supplemental Figure 1E–H).

Chemotaxis assays

Chemotaxis assays were performed using 12-well chemotaxis chambers and 5μm pore size filters (Neuroprobe) coated with 5ug/ml fibronectin. Human CXCL12 or CXCL11 (300-46 and 300-28B, Peprotech) were added to the lower wells and 105 cells added to the upper wells and incubated for 6 hours at 37°C. Filters were then removed, fixed in methanol, stained in 2% Toluidine blue and the cells that had migrated through to the underside of the filters was counted in 5 separate fields of view under 400X magnification. For transendothelial migration assays, human lung microvascular endothelial cells were first seeded onto transwell plate inserts with 8μm pore size, CXCL12 was added to the lower well and 105 A549 or H157 cells added to upper wells. After incubation for 6 hr at 37 °C, migrated cells were counted under fluorescence microscope. For the competitive chemotaxis assay 105 human lung microvascular endothelial cells were seeded onto 8μm pore size transwell inserts. The cells were allowed to adhere over night, the media was changed to starvation media and 30 ng/ml of CXCL12 was added to the lower wells containing the A549 cells. The inserts were placed in the lower wells and incubated for 6 hours at 37°C. The inserts were then removed, fixed in methanol, stained in 2% Toluidine blue and the cells that had migrated through to the underside of the insert was counted in 5 separate fields of view under 400X magnification.

Western Blotting

Immunoblotting for CXCR4, CXCR7, and factor VIII related antigen were performed as previously described (17).

Heterotopic human NSCLC-SCID mouse chimeras

We used a heterotopic model of human NSCLC in SCID-beige mice, as previously described (17). Age-matched female 6- to 8-week old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and were maintained under pathogen-free conditions and in compliance with institutional animal care regulations at the University of Virginia animal care facility. Briefly, 106 A549 cells in 1003l were injected subcutaneously into one flank of 6-week old female CB17-SCID beige mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) and tumors size monitored weekly. In some experiments, tumor-bearing SCID mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500μl of neutralizing anti-CXCL12 or control serum, containing 10mg goat IgG, 3 times per week, starting at the time of xeno-engraftment. This amount of anti-CXCL12 serum was found to specifically neutralize 1 μg of murine CXCL12 protein in bioassays without cross-reacting to a panel of other chemokines (17). Animals were euthanized at a designated times, and organs and blood samples were processed as described previously (3, 18–20). At the time of tissue harvest, primary tumors were removed from animals, their orthogonal diameters measured using Thorpe calipers (Biomedical Research Instruments, Rockville, MD), and tumor volume calculated as [volume = (d1 × d2 × d3) × 0.5236], where dn represents orthogonal diameter measurements.

Immunolocalization

Immunohistochemistry of factor VIII-related antigen, Ki67 and GFP were performed as previously described (18, 21). Briefly, paraffin-embedded tumor sections were de-paraffinized, subjected to antigen retrieval (HK080-9K, Biogenex, San Ramos, CA), fixed for 20min in 1:1 absolute methanol and 3% H2O2, rinsed in PBS, and then blocked (HK085-5K, Biogenex) at room temperature for 30 min followed by Avidin/Biotin blocking (SP-2001, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Then, a 1:800 dilution of anti-factor VIII related antibody, anti-Ki67 Ab-4 rabbit polyclonal antibody (RB-1510 Thermo Scientific) or control rabbit IgG or goat anti-GFP(Vector labs SP-0702) or control goat IgG (Sigma, I5356) were added and slides were incubated for 30 min. Slides were then rinsed with PBS, overlaid with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (PK-6101; Vector Labs), and incubated for an additional 30 min. Slides were rinsed twice with PBS, treated with streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase for 30 min, washed 3 times with PBS, incubated for 5–10 min in the substrate chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (SK-4100, Vector Laboratories) to allow color development and then rinsed with water. Finally, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. For GFP immunofluorescent staining, a 1:50 dilution of either mouse IgG or anti-GFP (SC-9996, Santa Cruz) was added and slides were incubated for 30 min. Slides were then rinsed with PBS, overlaid with AlexaFluor488 anti mouse IgG (A11001, Invitrogen), and incubated for an additional 30 min. Slides were again washed two times with PBS, and then coversliped using aqueous mounting media. For TUNEL staining, DeadEnd Colorimetric TUNEL System (G7130, Promega) was used, according to manufacturer specifications. For image analysis, we prepared 5 histological sections per tumor, from 5 mice per condition, and photographed 10 different fields from each section at 200X magnification using a Zeiss Image A1 microscope with an inline AxioCam HRc camera interfaced with a PC. Images were captured with AxioVision software (v.4.8) and analyzed using NIH ImageJ software. Data were expressed as percent of positive pixels per field.

Statistical analysis

The animal studies involved 5–10 mice bearing A549 tumors for each group. Data were analyzed on a personal computer using the Statview 5.0 statistical package (Abacus Concepts). Comparisons were evaluated by the ANOVA test with the post hoc analysis Bonferroni/Dunn. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM and differences were considered statistically significant if p values were less than 0.05.

Results

CXCR4 mediates chemotaxis of NSCLC cells to CXCL12

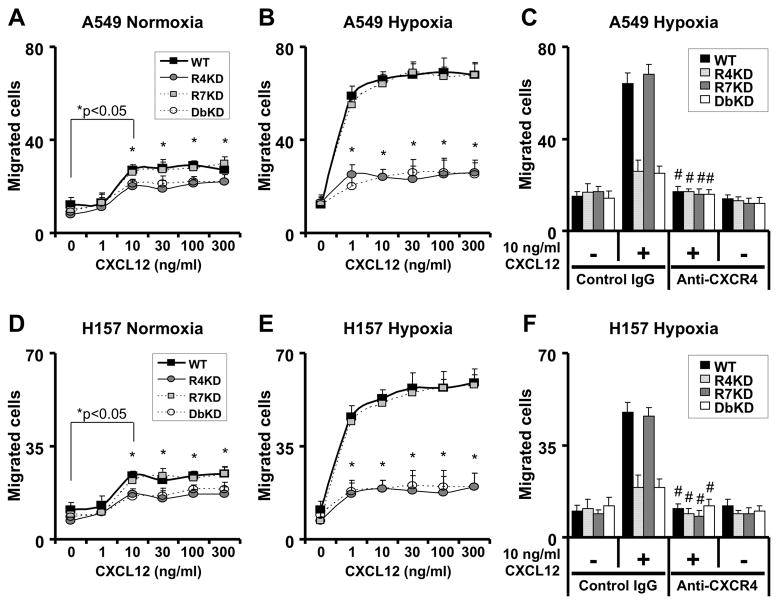

We began by examining the relative contribution of CXCR4 and CXCR7 to chemotaxis of A549 and H157 cells to varying concentrations of CXCL12. Under normoxic culture conditions, both cell lines displayed chemotaxis to concentration of CXCL12 between 10–300 ng/ml; this effect was significantly attenuated in both cell lines with CXCR4 knock-down and combined CXCR4/7 knockdown but was unaffected in CXCR7 knockdown lines (Figure 1A and 1D). Under hypoxic culture conditions, chemotaxis of cell lines with unmanipulated CXCR4/7 expression to CXCL12 was enhanced to concentrations as low as 1ng/ml; this effect was again greatly diminished in cell lines knocked down for CXCR4 and CXCR4/7 but was unaffected in lines knocked down for CXCR7 alone (Figure 1B and 1E).

Figure 1.

CXCR4 mediates migration of NSCLC cells. A549 (panels A–C) and H157 (D–E) cells were serum-starved and cultured in normoxic or hypoxic culture conditions for 24h before assessing chemotaxis to indicated concentrations of CXCL12 for 6 hours under normoxic (panels A and D) or hypoxic (B–C and E–F) culture conditions. Results are representative of 3 experiments; data shown represent mean ± SEM of cells per high-power field of n = 3 for each group. WT, non-transfected cells; R4KD, cells with stable knockdown of CXCR4; R7KD, cells with stable knockdown of CXCR7; DbKD, cells with stable knockdown of CXCR4 and CXCR7; *, p<0.05 in comparison of CXCR4-knock-down and CXCR4/CXCR7-knock-down cells as compared to non-transfected cells; #, p<0.05 compared to chemotaxis to CXCL12 without anti-CXCR4 exposure.

To confirm that CXCR4 is necessary for migration of NSCLC cell lines, we tested the effect of Ab-mediate neutralization of CXCR4 on chemotaxis of the cancer cells to CXCL12. As observed previously, both A549 and H157 lines exhibited brisk chemotaxis to 10ng/ml CXCL12 under hypoxic culture conditions; this effect was diminished in cell lines knocked down for CXCR4 and CXCR4/7, but not lines knocked down for CXCR7 alone (Figure 1C and 1F). In addition, chemotaxis of A549 and H157 lines with unmanipulated CXCR4/7 expression and those of lines knocked down for CXCR7 was abolished in the presence of neutralizing anti-CXCR4 antibodies, again demonstrating the critical role of CXCR4 in migration of these cells to CXCL12.

CXCR7 is dispensable for migration of NSCLC cell lines to CXCL11 and CXCL12

We employed several strategies to assess the contribution of CXCR7 to migration of NSCLC cells. First, we tested the effect of a neutralizing anti-CXCR7 antibody on migration of NSCLC cells in chemotaxis studies. Neutralization of CXCR7 did not influence the chemotaxis of A549 or H157 cells with unmanipulated CXCR4/7 expression to CXCL12, whereas cell lines knocked down for CXCR4 had diminished chemotaxis to CXCL12, again unaffected by CXCR7 neutralization (Supplemental figure 2). We next employed a transient siRNA approach to attenuate CXCR7 expression and assess its role in cell migration. Non-transfected A459 and H157 cells and cells with stable CXCR4 knockdown were subjected to CXCR7 siRNA transfection and were found to have efficient inhibition of CXCR7 expression (Supplemental Figure 2B), but showed no change in their migratory activities towards CXCL12 (Supplemental Figure 2C).

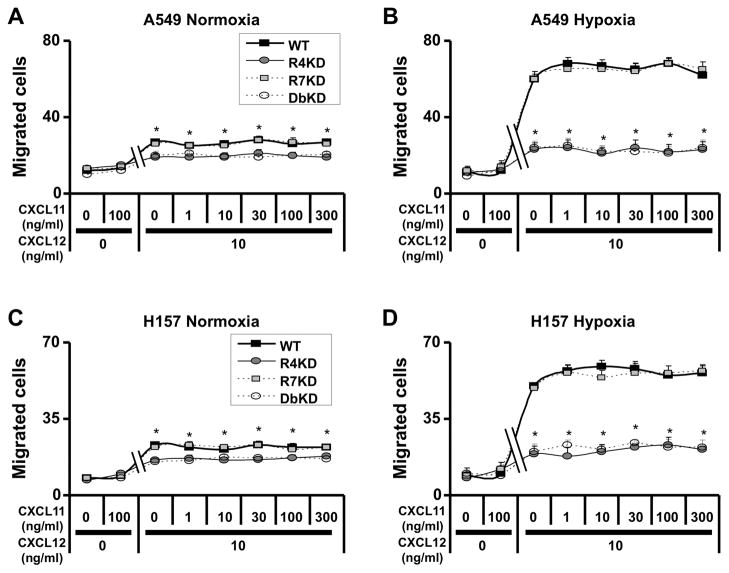

Since CXCL11 is another ligand for CXCR7, we next tested the effect of CXCL11 on chemotaxis of NSCLC cells. For both A549 and H157 lines, CXCL11 had no detectable influence on the migration of cells under normoxic and hypoxic culture conditions; this finding was unaffected in cells with stable knock-downs of CXCR4, CXCR7 or both. Furthermore, concentrations of CXCL11 between 1–300ng/ml did not interfere with CXCR4-dependent migration of A549 and H157 cells induced by 10ng/ml CXCL12 (Figure 2). These results suggest that CXCR7 does not contribute to the migration of NSCLC cells under our experimental conditions.

Figure 2.

CXCL11 does not interfere with the CXCL12/CXCR4 chemotactic behavior of NSCLC cells. A549 (panels A–B) and H157 (C–D) cells were serum-starved and cultured in normoxic or hypoxic culture conditions for 24h before chemotaxis assays. Cells were then subjected to chemotaxis assays in response to the indicated concentrations of CXCL11 (1 to 300 ng/ml) with or without 10 ng/ml CXCL12 for 6 hours under normoxic (panels A and C) or hypoxic (B and D) culture conditions. Results are representative of 3 experiments; data shown represent mean ± SEM of cells per high-power field of n = 3 for each group. *, p<0.05 in comparison of CXCR4-knock-down and CXCR4/CXCR7-knock-down cells as compared to non-transfected cells.

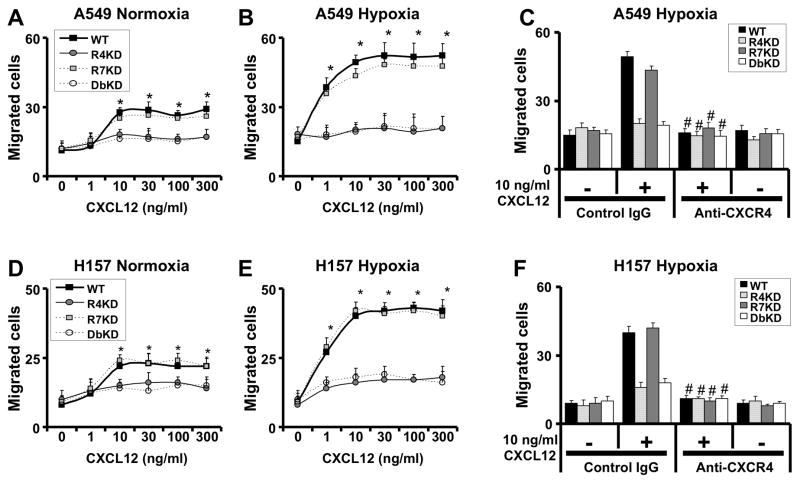

CXCR4 but not CXCR7 mediates the migration of NSCLC cells across endothelial barriers

A key feature of metastasis formation is the ability of cancer cells to cross endothelial barriers. We therefore tested the role of CXCR4 and CXCR7 in migration of NSCLC cells in modified in vitro chemotaxis assays that incorporate migration across a human microvascular endothelial cell barrier. As expected, A549 and H157 cells migrated across the endothelial barrier to CXCL12 under normoxic conditions and transendothelial migration was enhanced under hypoxic culture conditions (Figure 3). In addition, migration of A549 and H157 cell lines knocked down for CXCR4 and CXCR4/7 towards CXCL12 was significantly diminished, but lines knocked down for CXCR7 alone had comparable migration to CXCL12 as non-transfected cells (Figure 3). Similar to findings of chemotaxis in the absence of endothelial cells, Ab-mediated neutralization of CXCR4 inhibited the migration of A549 and H157 cells with intact CXCR4 expression to CXCL12 (Figure 3C and 3F).

Figure 3.

CXCR4 mediates migration of NSCLC cells across endothelial cell barriers. A549 (panels A–C) and H157 (D–F) cells were serum-starved and cultured in normoxic or hypoxic culture conditions for 24h before assessing trans-endothelial migration to indicated concentrations of CXCL12 for 6 hours under normoxic (panels A and D) or hypoxic (B–C and E–F) culture conditions. Results are representative of 3 experiments; data shown represent mean ± SEM of cells per high-power field of n = 3 for each group. *, p<0.05 in comparison of CXCR4-knock-down and CXCR4/CXCR7-knock-down cells to cells with intact expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7; #, p<0.05 compared to chemotaxis to CXCL12 without anti-CXCR4 exposure.

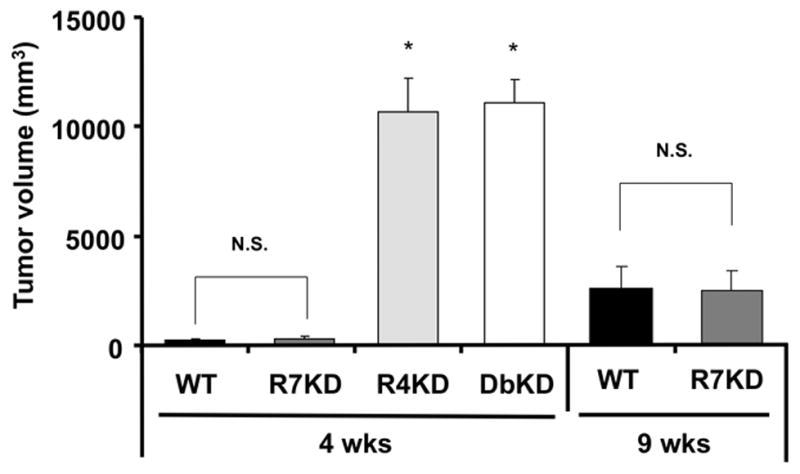

CXCR4-deficient NSCLC lines produce large vascular primary tumors with reduced metastases in vivo

To assess the biological relevance of our in vitro findings, we tested GFP-transfected A549 cells and A549 cells with stable knock-downs of CXCR4, CXCR7 and CXCR4 and CXCR7 in a heterotropic xenotransplantation animal model. Mice bearing CXCR4-knockdown and CXCR4/7-knockdown cancers were unexpectedly found to have dramatically larger primary tumors after only 4 weeks, necessitating animal euthanasia per animal welfare guidelines. In contrast, cells with intact CXCR4/CXCR7 expression and CXCR7-knock-down cells produced tumors that did not differ significantly in size; the tumors were at the limit of in vivo detection after 4 weeks and, after 9 weeks, were approximately a quarter of the size of CXCR4- and CXCR4/7-knock-downs tumors at 4 weeks (Figure 4). We reasoned that the observed differences in tumor size may be the result of differences in the rate of proliferation or apoptosis of cancer cells with disrupted CXCR4 or CXCR7 expression. However knock-down of CXCR4 or CXCR7 in A549 and H157 lines did not result in altered proliferation of the cell lines as compared to respective control cell lines, irrespective of the presence of CXCL12 in the media (Supplemental Figure 3A–B). Similarly, rate of apoptosis of tumor cells in response to staurosporine and methotrexate was unaffected by knock-down of CXCR4, CXCR7, or both in A549 or H157 cells and was unrelated to the presence of CXCL12 (Supplemental Figure 3C–D).

Figure 4.

Role of CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression on primary A549 tumor size in a heterotopic xenograft murine cancer model. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n = 7 to 9 mice per group. *, p<0.05 in comparison of CXCR4-knock-down and CXCR4/CXCR7-knock-down cells to cells with intact expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7; NS, no statistically significant difference.

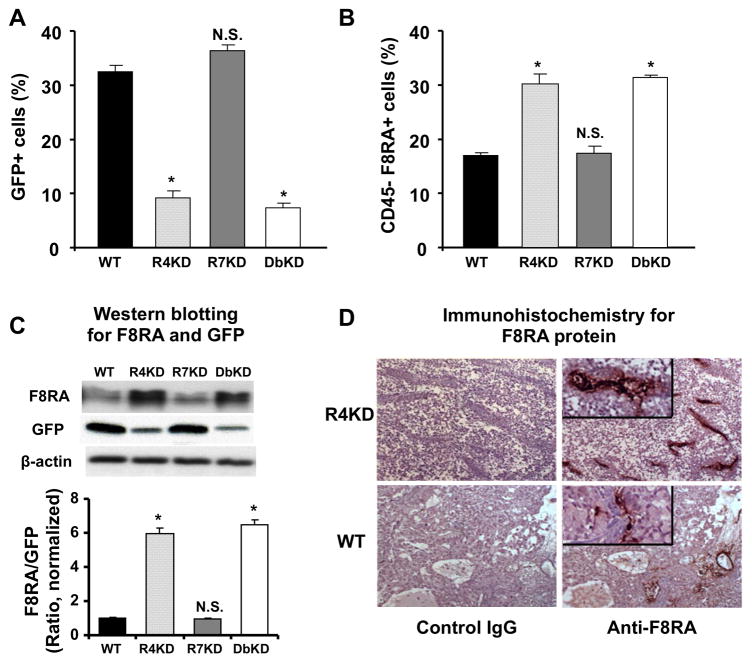

We next assessed the composition of the in vivo primary tumors. Due to the dramatic differences in the growth rate of the tumors in different cell types, it was not possible to examine CXCR4-knockdown and CXCR4/7-knockdown cancers beyond week 4; conversely, primary tumors caused by CXCR7-knock-down cells and cells with unmanipulated CXCR4/7 expression were at the limit of detection on week 4. We therefore harvested the tumors on week 4 from animals with CXCR4-knock-down and CXCR4/7-knock-down tumors and on week 9 from animals with CXCR7-knock-down tumors and tumors with unmanipulated CXCR4/7 expression. Grossly, tumors produced by CXCR4- and CXCR4/7-knock-down cells were friable and haemorrhagic as compared to the more compact tumors produced by A549 cells with intact CXCR4/CXCR7 expression and CXCR7-knock-down cells. We also found CXCR4- and CXCR4/7-knock-down tumors to have a lower proportion of cancer cells (detected on the basis of expression of GFP), but increased proportion of host-derived endothelial cells (defined as CD45-negative cells expressing factor VIII-related antigen) (Figure 5A–B). Consistent with this finding, CXCR4- and CXCR4/7-knock-down tumors had higher factor VIII related antigen protein content and lower GFP protein content as compared to cells with intact CXCR4/CXCR7 expression or CXCR7-knock-down tumors (Figure 5C). To better assess the vascular mass of the tumors, we also examined the resected tissue histologically. Immunohistochemical localization of endothelial cells revealed greatly increased vascularity within tumors generated by CXCR4-knock-down, as compared to non-transfected, A549 cells (Figure 5D). Histology also revealed that, in addition to being much larger and more vascular, the CXCR4 and CXCR4/7 knockdown tumors did contain many more necrotic cells than wildtype and CXCR7 knockdown tumors in vivo.

Figure 5.

Role of CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression on primary A549 tumor composition and vascularity. GFP-expressing cancer cells (panel A) and CD45-factor VIII related antigen (F8RA+) endothelial cells (panel B) were quantified in tumor cell suspensions by flow cytometry. Tumor F8RA and GFP protein content was quantified by Western blot and intensity of the corresponding band was quantified by densitometer and normalized to sample β-actin protein (panel C). Panel D shows representative immunohistochemical data (original magnification X100 for main panels, X400 for insets) of primary tumors of CXCR7-knockdown A549 cells and cells with intact CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression, stained with anti-F8RA antibody (right) or the control IgG (left). Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of n = 5 mice per group (panels A–B) and 3 replicates representative of 3 separate experiments (panel C). In all panels, R4KD and DbKD were obtained on week 4 and WT and R7KD samples were obtained on week 9. *, p<0.05 in comparison of CXCR4-knock-down and CXCR4/CXCR7-knock-down cells to cells with intact expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7; NS, no statistically significant difference.

To confirm that the increased size of primary tumors in CXCR4-knockdown cancers is attributable to the interaction of CXCR4 with CXCL12, we also assessed the effect of CXCL12 immuno-neutralization on the size and composition of primary tumors. CXCL12 neutralization resulted in reduced tumor size in CXCR4- and CXCR4/7-knock-down tumors associated with reduction of CD45− F8RA+ endothelial cells, but did no affect the size or vascularity of CXCR7-knockdown tumors or tumors with intact CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression (Supplemental Figure 4). These data indicate that primary tumors generated by CXCR4-knock-down A549 cells have greatly increased vascular mass, which contributes to their increased size; conversely, CXCR7 expression has no detectable effect on the size, cellularity or vascularity of primary tumors.

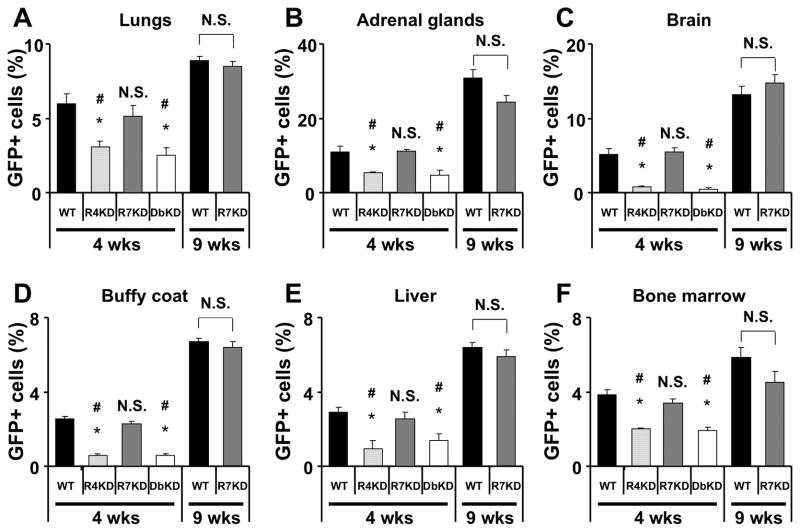

CXCR4-deficient NSCLC tumors have reduced metastatic potential in vivo

We next assessed extent of metastases from different cancer cells by evaluating the proportion of GFP-expressing cells in the lungs, liver, bone marrow, brain, adrenal glands and peripheral blood. As expected, the extent of metastases increased between 4 and 9 weeks in both A549 cells with intact CXCR4/CXCR7 expression and in CXCR7-knock-down cells (Figure 6 and supplemental figure 5). Despite their larger size, we found significantly fewer metastatic cells in cancers caused by A549 cells knocked down for CXCR4 and CXCR4/7 as compared to A549 cells knocked down for CXCR7 alone or cells with intact CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression 4 weeks after cancer implantation. Similar to the observations in vitro (Supplemental Figures 3A–D), we found no difference in the proportion of proliferating cells in the tumors based on Ki67 staining (22.5 +/− 1.9% in A549 cancer cells, 20.8 +/− 1.7% in CXCR4 knockdown cells, 19.1 +/− 3.1% in CXCR7-knockdown cells and 22.8 +/− 2% in CXCR4 and CXCR7 knockdown cells) or the proportion of apoptotic cells in the tumors based on TUNEL staining (5.8 +/− 1.2% in A549 cancer cells, 4.7 +/− 1.0% in CXCR4 knockdown cells, 7.0 +/− 0.85% in CXCR7-knockdown cells and 4.5 +/− 0.92% in CXCR4 and CXCR7 knockdown cells). Given that cancer cell adhesion to matrix is critical to metastasis formation and that CXCR7 had previously been implicated in cell adhesion (7, 22) we also examined the role of CXCR4 and CXCR7 in adhesion of A549 and H157 cells to plastic in vitro. We found that neither the presence of CXCL12 or nor the expression of CXCR4 or CXCR7 had any detectable effect on adhesion of either NSCLC line (Supplemental Figure 3E–F). Thus CXCR4 but not CXCR7 appears to be critical to metastasis formation in NSCLC.

Figure 6.

Role of CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression on A549 tumor metastasis. GFP-expressing cancer cells were quantified in various organ suspensions by flow cytometry. GFP-expressing metastatic cells were also detectable in the brain histologically (Supplemental figure 5). Data represent the mean ± SEM of n = 5 mice per group. *, p<0.05 in comparison to cells with intact expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7 at 4 weeks; #, p<0.05 in comparison to cells with intact expression of CXCR4 and CXCR7 at 9 weeks; NS, no statistically significant difference.

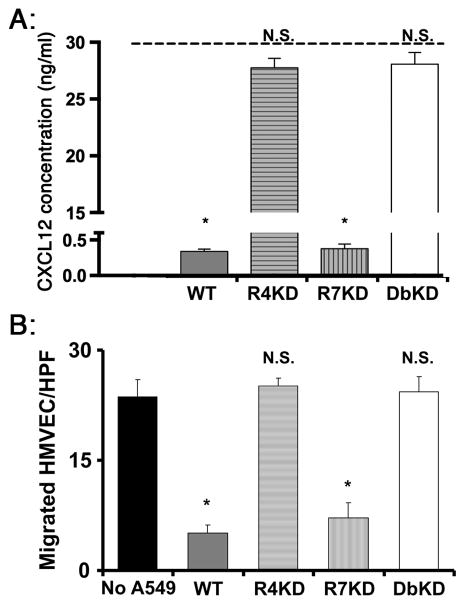

CXCR4 expression by A549 cells inhibits endothelial cell chemotaxis to CXCL12

To explain the unexpected finding of larger and more vascular primary tumors in the absence of CXCR4, we hypothesized that NSCLC CXCR4 competes with endothelial cells for CXCL12 in the niche of primary tumor. Since a major means of clearing chemokines, including CXCL12, is receptor-mediated cellular uptake, we first assessed the role of CXCR4 and CXCR7 on A549 in clearing exogenous CXCL12 from the media. We found that tumor cells with intact expression of CXCR4/7 and cells knocked down for CXCR7 showed rapid clearance of exogenous CXCL12, whereas cells that were knocked down for CXCR4 alone or both CXCR4/7 had little detectable clearance of CXCL12 (Figure 7A). We next assessed the effect of this process on the in vitro chemotaxis of endothelial cells to CXCL12 is the presence of A549 cancer cells. We found chemotaxis of endothelial cells to CXCL12 was markedly attenuated in the presence of non-transfected A549 cells and CXCR7-knock-down A549 cells (Figure 7B). In contrast, chemotaxis of endothelial cells to CXCL12 was not influenced by the presence of A549 cells that were knocked down for CXCR4 or CXCR4/7. These data suggest that cancer cell CXCR4 outcompetes endothelial cells for available CXCL12; as a result, CXCR4 promotes angiogenesis only in the absence of cancer cell CXCR4.

Figure 7.

Effect of NSCLC cell expression of CXCR4 on CXCL12. Panel A: Concentration of CXCL12 in the supernatant was measured after 24h culture of A549 cells in hypoxic conditions in the presence of 30ng/ml CXCL12 (represented by the dashed line). Panel B: After 24h culture in hypoxic conditions, chemotaxis of human microvascular endothelial cells (placed in the upper chambers of transwell plates) to 10 ng/ml CXCL12 in the lower chambers was quantified, in the presence or absence of A549 cells in the lower chambers. Results from each panel are representative of 3 experiments; data shown represent mean ± SEM of n = 3 for each group.*, p<0.05 in comparison to R4- and double-knockdown cells (panel A) and compared to chemotaxis of endothelial cells in the absence of A549 cells (panel B); NS, no statistically significant difference in comparison to chemotaxis of endothelial cells in the absence of A549 cells.

Discussion

In this study, we used NSCLC cell lines with stable knock-downs of CXCR4, CXCR7 or both receptors to investigate the contribution of CXCR4 and CXCR7 to NSCLC cell migration. CXCR4, but not CXCR7, was found to dictate the migration of NSCLC cells toward CXCL12 in vitro and to mediate metastases in vivo. We also unexpectedly discovered that tumor growth was accelerated in vivo in the absence of cancer cell CXCR4 expression, which was associated with increased tumor vascularity that was dependent on CXCL12. Finally, CXCR4 on A549 cells gave the cells the ability to outcompete endothelial cells in binding to CXCL12, indicating that CXCR4 expression in NSCLC has important roles in cell migration and metastasis but paradoxically attenuates vascular mass in the tumor microenvironment.

In the context of cancer biology, the CXCL12/CXCR4 molecular pathway has been shown to regulate the migration of tumor cells to metastatic sites in many cancers (23–29). In addition, several reports have suggested that a decrease in CXCR4 expression inhibits CXCL12-induced migration of prostate cancer or lung cancer cells (30–32). The discovery of CXCR7 as a promiscuous receptor for CXCL11 and CXCL12 ended the previously accepted exclusive association between CXCL12 and CXCR4. Although CXCR4 and CXCR7 have been reported to play diverse roles in the migration, proliferation and apoptosis of different cell types, our data confirm the exclusive association of CXCL12 with CXCR4 in migration and metastasis of NSCLC cells, and that CXCR7 or CXCL11 were not involved in this process. In this context, the literature suggests that CXCR7 is involved in the migration of some but not other cells: CXCR7 is crucial for proper migration of primordial germ cells or of interneurons toward their targets by attaining regulation of CXCL12 distribution or CXCR4 expression level (33, 34). However, in MCF breast cancer cells and in engrafted neural stem cells, CXCR7 does not mediate migration of these cells (7, 35). In addition, CXCR7 functions as a decoy receptor that does not activate G protein-mediated signaling in breast cancer cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (7, 33). Furthermore, expression of CXCR4 or CXCR7 did not influence apoptosis, proliferation or adhesion, in agreement with our previous report that CXCL12 did not significantly affect proliferation or apoptosis of NSCLC cells in vitro (17).

The present work also provides new insights into the biological significance of the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis in NSCLC. A striking finding in our study was that knock-down of CXCR4 in A549 cells resulted in greatly accelerated development of primary tumors in SCID mice that was associated with greatly increased tumor vasculature, suggesting that the absence of tumor CXCR4 expression resulted in enhanced recruitment or differentiation of endothelial cells or progenitors in the tumor. Indeed, substantial evidence supports the contention that CXCL12 is chemotactic to endothelial cells in vitro and is angiogenic in some circumstances (36–38). In contrast, previous work has demonstrated that CXCL12 concentrations are very low in CXCR4-expressing cancers and that immunoneutralization of CXCL12 in this setting attenuates metastases and prolonged survival in animal models without influencing primary tumor angiogenesis (17, 24, 39). In contrast, the present manuscript shows that, when CXCR4 is absent only on cancer cells but is present on endothelial cells, the abundant CXCL12 in the tumor milieu results in potent angiogenesis and accelerated tumor growth. Based on these observations and our data showing that cancer cell CXCR4 is sufficient to clear extracellular CXCL12 and to inhibit endothelial cell chemotaxis to CXCL12, we propose the following model: in the context of normal host where CXCR4 is expressed by both malignant and non-cancerous cells, the tumor microenvironment is devoid of extracellular CXCL12 due to uptake of the ligand by CXCR4 on the cancer cells; as a result, the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis does not participate in recruitment of endothelial cells and angiogenesis in the tumor, but plays a key role in recruiting cancer cells that have escaped into circulation to tissues with high levels of CXCL12 expression, such as the lungs, meninges, and bone marrow. The selective lack of CXCR4 on cancer cells, however, results in high levels of CXCL12 in the tumor microniche, resulting in robust recruitment of endothelial cells, enhanced angiogenesis and development of large, vascular tumors. Interestingly, in addition to being larger and more vascular, CXCR4 knock-down tumors were found to contain more areas of necrosis in vivo. Since CXCR4 knockdown cancer cells did not display altered proliferation or death in vitro, we speculate that increased necrosis may be the result of formation of abnormal microvasculature. Alternatively, it is possible that the increased necrosis is an indirect consequence of altered tumor microenvironment in vivo.

In summary, our results demonstrate that CXCL12 and CXCR4 have a single ligand-single receptor relationship in mediating NSCLC migration and metastasis, and in the context of NSCLC that expresses CXCR4, the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis is not involved in angiogenesis of the primary tumor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute HL073848 (BM), HL098329 (BM, RMS), HL066027 and HL098526 (RMS).

Abbreviations

- DbKD

CXCR4-CXCR7-double-knockdown

- F8RA

Factor-8-related antigen

- GFP

Green fluorescence protein

- NGS

Normal goat serum

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- R4KD

CXCR4-knockdown

- R7KD

CXCR7-knockdown

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips RJ, Mestas J, Gharaee-Kermani M, et al. Epidermal growth factor and hypoxia-induced expression of CXC chemokine receptor 4 on non-small cell lung cancer cells is regulated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway and activation of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(23):22473–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schioppa T, Uranchimeg B, Saccani A, et al. Regulation of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2003;198(9):1391–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger JA, Kipps TJ. CXCR4: a key receptor in the crosstalk between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Blood. 2006;107(5):1761–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun X, Cheng G, Hao M, et al. CXCL12 / CXCR4 / CXCR7 chemokine axis and cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(4):709–22. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9256-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns JM, Summers BC, Wang Y, et al. A novel chemokine receptor for SDF-1 and I-TAC involved in cell survival, cell adhesion, and tumor development. J Exp Med. 2006;203(9):2201–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luker KE, Steele JM, Mihalko LA, Ray P, Luker GD. Constitutive and chemokine-dependent internalization and recycling of CXCR7 in breast cancer cells to degrade chemokine ligands. Oncogene. 2010;29(32):4599–610. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grymula K, Tarnowski M, Wysoczynski M, et al. Overlapping and distinct role of CXCR7-SDF-1/ITAC and CXCR4-SDF-1 axes in regulating metastatic behavior of human rhabdomyosarcomas. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(11):2554–68. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miekus K, Jarocha D, Trzyna E, Majka M. Role of I-TAC-binding receptors CXCR3 and CXCR7 in proliferation, activation of intracellular signaling pathways and migration of various tumor cell lines. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2010;48(1):104–11. doi: 10.2478/v10042-008-0091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarnowski M, Liu R, Wysoczynski M, Ratajczak J, Kucia M, Ratajczak MZ. CXCR7: a new SDF-1-binding receptor in contrast to normal CD34(+) progenitors is functional and is expressed at higher level in human malignant hematopoietic cells. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85(6):472–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hattermann K, Held-Feindt J, Lucius R, et al. The chemokine receptor CXCR7 is highly expressed in human glioma cells and mediates antiapoptotic effects. Cancer Res. 2010;70(8):3299–308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miao Z, Luker KE, Summers BC, et al. CXCR7 (RDC1) promotes breast and lung tumor growth in vivo and is expressed on tumor-associated vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(40):15735–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610444104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh RK, Lokeshwar BL. The IL-8-regulated chemokine receptor CXCR7 stimulates EGFR signaling to promote prostate cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71(9):3268–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng K, Li HY, Su XL, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR7 regulates the invasion, angiogenesis and tumor growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:31. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kollmar O, Rupertus K, Scheuer C, et al. CXCR4 and CXCR7 regulate angiogenesis and CT26. WT tumor growth independent from SDF-1. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(6):1302–15. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Lutz M, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. The stromal derived factor-1/CXCL12-CXC chemokine receptor 4 biological axis in non-small cell lung cancer metastases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(12):1676–86. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-071OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Addison CL, Daniel TO, Burdick MD, et al. The CXC chemokine receptor 2, CXCR2, is the putative receptor for ELR+ CXC chemokine-induced angiogenic activity. J Immunol. 2000;165(9):5269–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arenberg DA, Kunkel SL, Polverini PJ, Glass M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. Inhibition of interleukin-8 reduces tumorigenesis of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(12):2792–802. doi: 10.1172/JCI118734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arenberg DA, Kunkel SL, Polverini PJ, et al. Interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) is an angiostatic factor that inhibits human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumorigenesis and spontaneous metastases. J Exp Med. 1996;184(3):981–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keane MP, Arenberg DA, Lynch JP, 3rd, et al. The CXC chemokines, IL-8 and IP-10, regulate angiogenic activity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 1997;159(3):1437–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai X, Tan Y, Cai S, et al. The role of CXCR7 on the adhesion, proliferation and angiogenesis of endothelial progenitor cells. J Cell Mol Med. 15(6):1299–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geminder H, Sagi-Assif O, Goldberg L, et al. A possible role for CXCR4 and its ligand, the CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1, in the development of bone marrow metastases in neuroblastoma. J Immunol. 2001;167(8):4747–57. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410(6824):50–6. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan J, Mestas J, Burdick MD, et al. Stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) and CXCR4 in renal cell carcinoma metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scotton CJ, Wilson JL, Scott K, et al. Multiple actions of the chemokine CXCL12 on epithelial tumor cells in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62(20):5930–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith MC, Luker KE, Garbow JR, et al. CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(23):8604–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taichman RS, Cooper C, Keller ET, Pienta KJ, Taichman NS, McCauley LK. Use of the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 pathway in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Res. 2002;62(6):1832–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandercappellen J, Van Damme J, Struyf S. The role of CXC chemokines and their receptors in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(2):226–44. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong JS, Pai HK, Hong KO, et al. CXCR-4 knockdown by small interfering RNA inhibits cell proliferation and invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38(2):214–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xing Y, Liu M, Du Y, et al. Tumor cell-specific blockade of CXCR4/SDF-1 interactions in prostate cancer cells by hTERT promoter induced CXCR4 knockdown: A possible metastasis preventing and minimizing approach. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(11):1839–48. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.11.6862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Zhang B, Lin Y, Yang Y, Liu X, Lu F. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 inhibits SDF-1alpha-induced migration of non-small cell lung cancer by decreasing CXCR4 expression. Cancer Lett. 2008;269(1):46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boldajipour B, Mahabaleshwar H, Kardash E, et al. Control of chemokine-guided cell migration by ligand sequestration. Cell. 2008;132(3):463–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez-Alcaniz JA, Haege S, Mueller W, et al. Cxcr7 controls neuronal migration by regulating chemokine responsiveness. Neuron. 2011;69(1):77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carbajal KS, Schaumburg C, Strieter R, Kane J, Lane TE. Migration of engrafted neural stem cells is mediated by CXCL12 signaling through CXCR4 in a viral model of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(24):11068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006375107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvucci O, Yao L, Villalba S, Sajewicz A, Pittaluga S, Tosato G. Regulation of endothelial cell branching morphogenesis by endogenous chemokine stromal-derived factor-1. Blood. 2002;99(8):2703–11. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tachibana K, Hirota S, Iizasa H, et al. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature. 1998;393(6685):591–4. doi: 10.1038/31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takabatake Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, et al. The CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 axis is essential for the development of renal vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(8):1714–23. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schrader AJ, Lechner O, Templin M, et al. CXCR4/CXCL12 expression and signalling in kidney cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(8):1250–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.