Abstract

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) can be used to identify white coat hypertension and guide hypertensive treatment. We determined the percentage of ABPM claims submitted between 2007–2010 that were reimbursed. Among 1,970 Medicare beneficiaries with submitted claims, ABPM was reimbursed for 93.8% of claims that had an ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 (“elevated blood pressure reading without diagnosis of hypertension”) versus 28.5% of claims without this code. Among claims without an ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 listed, those for the component (e.g., recording, scanning analysis, physician review, reporting) versus full ABPM procedures and performed by institutional versus non-institutional providers were each more than two times as likely to be successfully reimbursed. Of the claims reimbursed, the median payment was $52.01 (25–75th percentiles: $32.95–$64.98). In conclusion, educating providers on the ABPM claims reimbursement process and evaluation of Medicare reimbursement may increase the appropriate use of ABPM and improve patient care.

Keywords: White Coat Hypertension, Blood Pressure Monitoring, Ambulatory, Medicare, Insurance, Health, Reimbursement

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (US), the diagnosis and management of hypertension are primarily guided by blood pressure (BP) readings obtained in the clinic setting [1, 2]. However, many persons exhibit a white coat effect, defined as having BP that is higher in the clinic versus out-of-clinic setting, or white coat hypertension (WCH), defined as having hypertension based on clinic measurements despite having non-elevated BP outside of the clinic setting [3]. WCH is estimated to be present in 15% to 25% of individuals with elevated clinic BP [4]. It is generally accepted that the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with WCH is low compared with those whose clinic and ambulatory BPs are both elevated (i.e., sustained hypertension) [4]. Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) is considered the “gold standard” for identifying WCH, and has been found to be a cost-effective method to avoid overuse of antihypertensive medications [5, 6].

In 2001, the US Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) approved reimbursement for ABPM for patients with suspected WCH [7]. Despite the high prevalence of WCH in individuals with elevated clinic BP, only 0.1% of Medicare beneficiaries had a claim submitted for ABPM between 2007 and 2010 (see accompanying Shimbo et al. JASH article in current issue). These findings suggest that ABPM is being underutilized in Medicare beneficiaries. Concerns about unreimbursed claims and low reimbursement amounts may be barriers to performing ABPM in Medicare beneficiaries. Identifying factors that are associated with the successful reimbursement of ABPM by CMS may encourage its more widespread use in clinical practice. We examined the percentage of Medicare ABPM claims submitted that were reimbursed and the factors associated with successful reimbursement. We also examined the amounts reimbursed to providers and the factors associated with higher reimbursement amounts.

METHODS

We conducted a study of Medicare beneficiaries using the 2006–2010 national 5% random sample from the CMS. Medicare is a US federal health insurance program administered by the CMS that covers individuals 65 years of age and older, on disability, or who have end-stage renal disease. Coverage may be chosen on a fee-for-service basis or through contracts with managed care organizations (i.e., Part C coverage also known as Medicare Advantage). Medicare data used for the current analyses were derived from the beneficiary enrollment file and fee-for-service Parts A (inpatient), B (outpatient), and D (pharmacy) claims. These data sources provide Medicare claims and assessment data linked by beneficiary across the continuum of care. We excluded Medicare beneficiaries with coverage through Part C from the current analysis, as claims are incomplete for these individuals. CMS and the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the study.

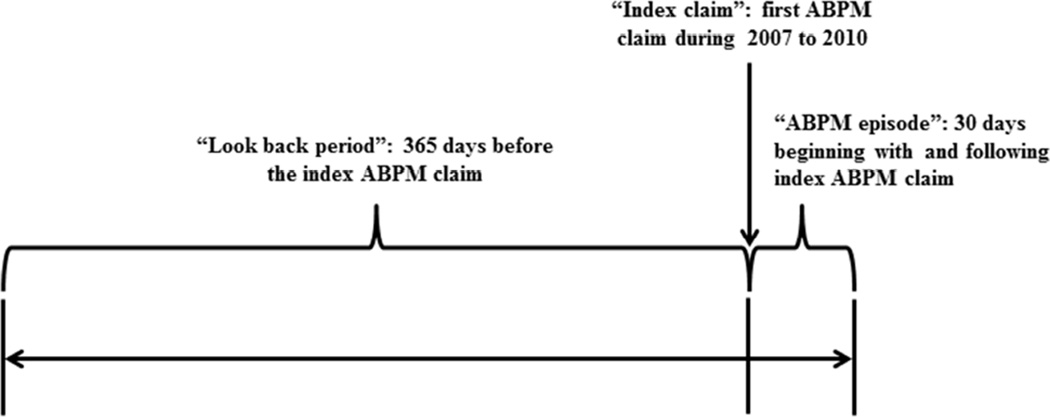

ABPM procedures were identified from 2007–2010 claims submitted through Medicare Part B. ABPM claims from 2006 were not included, allowing for a 365 day “look back” preceding the ABPM index claim that was used to define covariates, including healthcare utilization and comorbidities, for Medicare beneficiaries. Claims included those with Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for the “full” ABPM procedure (HCPCS code 93784) or the recording, scanning analysis, physician review, and reporting components (HCPCS codes 93786, 93788, or 93790) (Table 1). Each beneficiary’s first ABPM claim was used as his/her “index” claim. As all ABPM components may not be performed on the same date, we created an ABPM “episode” for each participant. The ABPM episode consisted of all ABPM claims submitted within a 30 day period beginning with and including the index claim (Figure 1). Reimbursement amounts are listed on ABPM claims. We categorized beneficiaries by whether or not at least one of their ABPM claims in the episode period was reimbursed, defined as a CMS payment of over $0. Beneficiaries were required to have continuous full Medicare coverage (Medicare Parts A, B and D coverage) and to reside in the 50 US states or Washington DC for the entire 365 day look back period through the 30 day ABPM episode period. In order to have the sample represent the general population, we excluded beneficiaries who were < 65 years of age at the start of the 365 day look back period.

Table 1.

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes used to identify ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) in Medicare claims.

| HCPCS code | Description |

|---|---|

| 93784 | ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape

and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; including recording, scanning analysis, interpretation and report. |

| 93786 | ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape

and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; recording only |

| 93788 | ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape

and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; scanning analysis with report. |

| 93790 | ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape

and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; physician review with interpretation and report. |

Figure 1.

Study design to examine the reimbursement of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) claims in Medicare

Covariates

A priori-selected covariates were used to characterize Medicare beneficiaries with ABPM claims. Demographics, defined using the Medicare beneficiary enrollment file, included age, gender, race/ethnicity grouped as non-Hispanic white or other, Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility for the entire look back period as a measure of poverty, and urban/rural status as defined using Rural/Urban Commuting Area codes. Diabetes, coronary heart disease, and kidney disease were defined using claims during the look back period and previously published algorithms (Appendix 1). We also determined the number of outpatient visits for hypertension each beneficiary had during the look back period. This was defined by the number of separate days with an outpatient physician evaluation and management claim with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code of 401.x (i.e. “malignant, benign or unspecified essential hypertension”). The number of antihypertensive medication classes each beneficiary filled during the look back period was identified from the Medicare Part D file. Antihypertensive medication classes were defined as listed in the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) guidelines [8] and were updated by two authors (D.S., S.O.) to include newer medications. We defined WCH by the ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 (i.e. “elevated blood pressure reading without diagnosis of hypertension”). Beneficiaries were considered to have a history of WCH if an ICD-9 code of 796.2 was present on one or more claims during the look back period. A WCH diagnosis was considered to be made concurrent with a beneficiary’s ABPM claim if the diagnosis code of 796.2 was listed on the claim. We also categorized beneficiaries by whether at least one ABPM claim was submitted by a cardiologist (specialty code “06”), an institutional provider (e.g. hospital outpatient department, rural health clinic, or dialysis center) versus by non-institutional providers (e.g. individual physician, clinical laboratory, or free-standing ambulatory surgery center)[9], and for a full procedure versus for component procedures.

Statistical Analyses

The percentage of beneficiaries with a reimbursed ABPM claim was calculated, overall and separately for beneficiaries with and without a WCH diagnosis code on their ABPM claim. Next, among those without a WCH diagnosis code on an ABPM claim, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for having a reimbursed ABPM claim were calculated using Poisson regression models and sandwich estimators. Relative risks were calculated for the covariates described above in unadjusted models and in a model that included all of these covariates. Among those without a WCH diagnosis code on their ABPM claims, we calculated the ten most common diagnosis codes for claims that were reimbursed and, separately, for those that were not reimbursed. We did not perform these calculations in beneficiaries with a WCH diagnosis code on their ABPM claims, since only a small percentage of these were not reimbursed.

For beneficiaries whose ABPM claims were reimbursed, we calculated the total amounts reimbursed, as well as the amounts paid for the full ABPM procedure and for each component. Differences in amounts reimbursed for full ABPM procedure claims across levels of the a priori selected covariates were calculated using general linear models. Models were conducted unadjusted and in a model that included all of these covariates. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Between 2007 and 2010, ABPM claims were submitted for 1,970 Medicare beneficiaries. Overall, 1,347 (68.4%) of the 1,970 Medicare beneficiaries had an ABPM claim reimbursed (Table 2). A WCH diagnosis was listed on 1,202 (61.0%) of ABPM claims. Claims were reimbursed for 1,128 (93.8%) of beneficiaries with a WCH diagnosis on their ABPM claim. In contrast, claims were reimbursed for only 219 (28.5%) of beneficiaries without a WCH diagnosis on their ABPM claim. Beneficiaries were more likely to have a WCH diagnosis on their ABPM claim if they had a history of WCH, a claim for the full ABPM procedure, or an ABPM claim submitted by a cardiologist or institutional provider. Additionally, beneficiaries with a WCH diagnosis on their ABPM claim had fewer outpatient visits for hypertension and were taking fewer classes of antihypertensive medication during the look back period, were less likely to have a history of diabetes, and were more likely to have an urban residence than those who did not have a WCH diagnosis on their claim.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries in the 2007–2010 5% sample, overall and by the presence of a white coat hypertension (WCH) diagnosis on an ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) claim.

| WCH diagnosis on an ABPM claim |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall (n=1970) |

No (n=768) | Yes (n=1202) | p-value |

| Reimbursed ABPM claim | ||||

| No | 623 (31.6%) | 549 (71.5%) | 74 (6.2%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 1347 (68.4%) | 219 (28.5%) | 1128 (93.8%) | |

| History of WCH | ||||

| No | 1755 (89.1%) | 730 (95.1%) | 1025 (85.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 215 (10.9%) | 38 (4.9%) | 177 (14.7%) | |

| ABPM procedure claim type† | ||||

| Full procedure | 1546 (78.5%) | 573 (74.6%) | 973 (80.9%) | 0.001 |

| Components | 424 (21.5%) | 195 (25.4%) | 229 (19.1%) | |

| ABPM claim filed by cardiologist | ||||

| No | 1102 (55.9%) | 461 (60.0%) | 641 (53.3%) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 868 (44.1%) | 307 (40.0%) | 561 (46.7%) | |

| ABPM claim filed by an institutional provider†† |

<.001 | |||

| No | 1676 (85.1%) | 1061 (88.3%) | 615 (80.1%) | |

| Yes | 294 (14.9%) | 141 (11.7%) | 153 (19.9%) | |

| Number of hypertension diagnoses before ABPM claims |

||||

| 0 | 230 (11.7%) | 73 (9.5%) | 157 (13.1%) | 0.034 |

| 1 to 5 | 1064 (54.0%) | 415 (54.0%) | 649 (54.0%) | |

| 6 or more | 676 (34.3%) | 280 (36.5%) | 396 (32.9%) | |

| Number of antihypertensive medication classes filled before ABPM claims |

||||

| 0 | 258 (13.1%) | 68 (8.9%) | 190 (15.8%) | <.001 |

| 1 or 2 | 708 (35.9%) | 278 (36.2%) | 430 (35.8%) | |

| 3 or more | 1004 (51.0%) | 422 (54.9%) | 582 (48.4%) | |

| History of diabetes | ||||

| No | 1479 (75.1%) | 558 (72.7%) | 921 (76.6%) | 0.047 |

| Yes | 491 (24.9%) | 210 (27.3%) | 281 (23.4%) | |

| History of coronary heart disease | ||||

| No | 1148 (58.3%) | 458 (59.6%) | 690 (57.4%) | 0.327 |

| Yes | 822 (41.7%) | 310 (40.4%) | 512 (42.6%) | |

| History of kidney disease | ||||

| No | 1626 (82.5%) | 624 (81.3%) | 1002 (83.4%) | 0.229 |

| Yes | 344 (17.5%) | 144 (18.8%) | 200 (16.6%) | |

| Age, years | 0.719 | |||

| 65 to 74 | 908 (46.1%) | 346 (45.1%) | 562 (46.8%) | |

| 75 to 84 | 816 (41.4%) | 322 (41.9%) | 494 (41.1%) | |

| 85 and above | 246 (12.5%) | 100 (13.0%) | 146 (12.1%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1361 (69.1%) | 518 (67.4%) | 843 (70.1%) | 0.209 |

| Male | 609 (30.9%) | 250 (32.6%) | 359 (29.9%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1758 (89.2%) | 683 (88.9%) | 1075 (89.4%) | 0.726 |

| Other | 212 (10.8%) | 85 (11.1%) | 127 (10.6%) | |

| Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility | ||||

| No | 1666 (84.6%) | 647 (84.2%) | 1019 (84.8%) | 0.751 |

| Yes | 304 (15.4%) | 121 (15.8%) | 183 (15.2%) | |

| Rural/urban residence | ||||

| Urban | 1380 (70.1%) | 485 (63.2%) | 895 (74.5%) | <.001 |

| Rural | 590 (29.9%) | 283 (36.8%) | 307 (25.5%) | |

A WCH diagnosis is defined as ICD-9 code 796.2 (“Elevated blood pressure reading without diagnosis of hypertension”)

The full ABPM procedure is defined as an ABPM claim with Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code 93784, described as “ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; including recording, scanning analysis, interpretation and report.” Other HCPCS codes (93786, 93788, and 93790) are for individual ABPM procedure components.

Claims filed by an institutional provider are defined as those in the outpatient file. Claims filed by a non-institutional provider are defined as those in the carrier file.

Table 3 shows the proportion of beneficiaries with reimbursed ABPM claims. Claims for ABPM procedure components and claims filed by institutional providers were more likely to be reimbursed. Having a history of WCH was associated with a higher likelihood of a reimbursement in the overall population, but not among those without a WCH diagnosis code on their ABPM claims. Having a rural residence was associated with a lower likelihood of reimbursement in the overall population, but with a higher likelihood of reimbursement among those without a WCH diagnosis on their ABPM claims. Table 4 shows unadjusted and multivariable adjusted relative risks for having a reimbursed ABPM claim for participants with a WCH code on their ABPM claim. Among beneficiaries without a WCH code on their ABPM claims, those who had only ABPM procedure component claims versus a full procedure claim or a claim filed by an institutional provider were more likely to have their ABPM claim reimbursed after multivariable adjustment. Among beneficiaries without a WCH diagnosis on their ABPM claims, more than 80% had ICD-9 diagnosis codes for essential hypertension listed on both reimbursed (Supplemental Tables 1) and unreimbursed claims (Supplemental Table 2). Other diagnoses were coded on fewer than 10% of these claims.

Table 3.

Number and percent of Medicare beneficiaries in the 2007–2010 5% sample with a reimbursed ABPM claim, overall and among those without a white coat hypertension (WCH) diagnosis on a claim.

| All beneficiaries | Without WCH diagnosis on ABPM claim |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABPM claim reimbursed | ABPM claim reimbursed | |||||

| Characteristics | No | Yes | p-value | No | Yes | p-value |

| Overall | 623 (31.6%) | 1347 (68.4%) | -- | 549 (71.5%) | 219 (28.5%) | -- |

| History of WCH | ||||||

| No | 585 (33.3%) | 1170 (66.7%) | <.001 | 526 (72.1%) | 204 (27.9%) | 0.125 |

| Yes | 38 (17.7%) | 177 (82.3%) | 23 (60.5%) | 15 (39.5%) | ||

| Full ABPM procedure claim type† | ||||||

| Full procedure | 547 (35.4%) | 999 (64.6%) | <.001 | 482 (84.1%) | 91 (15.9%) | <.001 |

| Components | 76 (17.9%) | 348 (82.1%) | 67 (34.4%) | 128 (65.6%) | ||

| ABPM claim filed by cardiologist | ||||||

| No | 362 (32.8%) | 740 (67.2%) | 0.188 | 319 (69.2%) | 142 (30.8%) | 0.085 |

| Yes | 261 (30.1%) | 607 (69.9%) | 230 (74.9%) | 77 (25.1%) | ||

| ABPM claim filed by an institutional provider†† | ||||||

| No | 577 (34.4%) | 1099 (65.6%) | <.001 | 512 (83.3%) | 103 (16.7%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 46 (15.6%) | 248 (84.4%) | 37 (24.2%) | 116 (75.8%) | ||

| Number of hypertension diagnoses before ABPM claims |

||||||

| 0 | 64 (27.8%) | 166 (72.2%) | 0.397 | 54 (74.0%) | 19 (26.0%) | 0.880 |

| 1 to 5 | 345 (32.4%) | 719 (67.6%) | 295 (71.1%) | 120 (28.9%) | ||

| 6 or more | 214 (31.7%) | 462 (68.3%) | 200 (71.4%) | 80 (28.6%) | ||

| Number of antihypertensive medication classes filled before ABPM claims |

||||||

| 0 | 72 (27.9%) | 186 (72.1%) | 0.274 | 54 (79.4%) | 14 (20.6%) | 0.315 |

| 1 or 2 | 220 (31.1%) | 488 (68.9%) | 196 (70.5%) | 82 (29.5%) | ||

| 3 or more | 197 (34.1%) | 381 (65.9%) | 183 (69.6%) | 80 (30.4%) | ||

| History of diabetes | ||||||

| No | 468 (31.6%) | 1011 (68.4%) | 0.975 | 405 (72.6%) | 153 (27.4%) | 0.273 |

| Yes | 155 (31.6%) | 336 (68.4%) | 144 (68.6%) | 66 (31.4%) | ||

| History of coronary heart disease | ||||||

| No | 365 (31.8%) | 783 (68.2%) | 0.848 | 316 (69.0%) | 142 (31.0%) | 0.063 |

| Yes | 258 (31.4%) | 564 (68.6%) | 233 (75.2%) | 77 (24.8%) | ||

| History of kidney disease | ||||||

| No | 515 (31.7%) | 1111 (68.3%) | 0.920 | 448 (71.8%) | 176 (28.2%) | 0.692 |

| Yes | 108 (31.4%) | 236 (68.6%) | 101 (70.1%) | 43 (29.9%) | ||

| Age, years | ||||||

| 65 to 74 | 287 (31.6%) | 621 (68.4%) | 0.944 | 251 (72.5%) | 95 (27.5%) | 0.837 |

| 75 to 84 | 256 (31.4%) | 560 (68.6%) | 227 (70.5%) | 95 (29.5%) | ||

| 85 and above | 80 (32.5%) | 166 (67.5%) | 71 (71.0%) | 29 (29.0%) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 417 (30.6%) | 944 (69.4%) | 0.160 | 368 (71.0%) | 150 (29.0%) | 0.696 |

| Male | 206 (33.8%) | 403 (66.2%) | 181 (72.4%) | 69 (27.6%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 553 (31.5%) | 1205 (68.5%) | 0.644 | 483 (70.7%) | 200 (29.3%) | 0.182 |

| Other | 70 (33.0%) | 142 (67.0%) | 66 (77.6%) | 19 (22.4%) | ||

| Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility | ||||||

| No | 523 (31.4%) | 1143 (68.6%) | 0.605 | 456 (70.5%) | 191 (29.5%) | 0.155 |

| Yes | 100 (32.9%) | 204 (67.1%) | 93 (76.9%) | 28 (23.1%) | ||

| Rural/urban residence | ||||||

| Urban | 412 (29.9%) | 968 (70.1%) | 0.010 | 363 (74.8%) | 122 (25.2%) | 0.007 |

| Rural | 211 (35.8%) | 379 (64.2%) | 186 (65.7%) | 97 (34.3%) | ||

A WCH diagnosis is defined as ICD-9 code 796.2 (“Elevated blood pressure reading without diagnosis of hypertension”)

The full ABPM procedure is defined as an ABPM claim with Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code 93784, described as “ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; including recording, scanning analysis, interpretation and report.” Other HCPCS codes (93786, 93788, and 93790) are for individual ABPM procedure components.

Claims filed by an institutional provider are defined as those in the outpatient file. Claims filed by a non-institutional provider are defined as those in the carrier file.

Table 4.

Multivariable adjusted relative risks for a reimbursed ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) claim associated with Medicare beneficiary characteristics among those without a claim listing a white coat hypertension (WCH) diagnosis (n=768).

| Relative risk (95% confidence interval) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Fully adjusted††† | |

| History of WCH | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.41 (0.94, 2.13) | 1.37 (0.99, 1.90) |

| ABPM procedure claim type† | ||

| Full procedure | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Components | 4.13 (3.34, 5.12) | 2.05 (1.45, 2.88) |

| ABPM claim filed by cardiologist | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.81 (0.64, 1.03) | 0.94 (0.77, 1.15) |

| ABPM claim filed by an institutional provider†† | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 4.53 (3.72, 5.52) | 2.47 (1.79, 3.42) |

| Number of hypertension diagnoses before ABPM claims |

||

| 0 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1 to 5 | 1.11 (0.73, 1.68) | 1.07 (0.76, 1.52) |

| 6 or more | 1.10 (0.71, 1.69) | 0.97 (0.67, 1.42) |

| Number of antihypertensive medication classes filled before ABPM claims |

||

| 0 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1 or 2 | 1.43 (0.87, 2.36) | 1.21 (0.78, 1.87) |

| 3 or more | 1.42 (0.87, 2.31) | 1.35 (0.87, 2.10) |

| History of diabetes | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.15 (0.90, 1.46) | 1.16 (0.92, 1.45) |

| History of coronary heart disease | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.80 (0.63, 1.02) | 0.83 (0.67, 1.03) |

| History of kidney disease | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.06 (0.80, 1.40) | 0.97 (0.76, 1.23) |

| Age, years | ||

| 65 to 74 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 75 to 84 | 1.07 (0.84, 1.37) | 1.04 (0.84, 1.28) |

| 85 and above | 1.06 (0.74, 1.50) | 0.99 (0.74, 1.33) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Male | 0.95 (0.75, 1.21) | 0.99 (0.80, 1.23) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Other | 0.76 (0.51, 1.15) | 0.94 (0.64, 1.36) |

| Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility | ||

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 0.78 (0.55, 1.11) | 0.81 (0.60, 1.10) |

| Rural/urban residence | ||

| Urban | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Rural | 1.36 (1.09, 1.70) | 1.09 (0.89, 1.33) |

A WCH diagnosis is defined as ICD-9 code 796.2 (“Elevated blood pressure reading without diagnosis of hypertension”)

The full ABPM procedure is defined as an ABPM claim with Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code 93784, described as “ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; including recording, scanning analysis, interpretation and report.” Other HCPCS codes (93786, 93788, and 93790) are for individual ABPM procedure components.

Claims filed by an institutional provider are defined as those in the outpatient file. Claims filed by a non-institutional provider are defined as those in the carrier file.

Fully adjusted risk ratios are adjusted for all characteristics presented in the table.

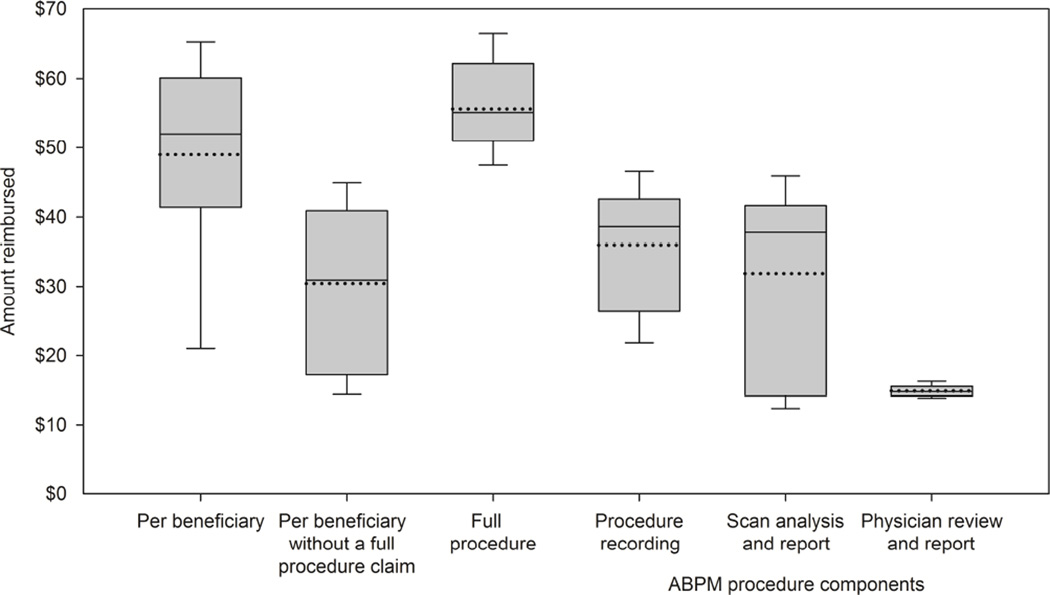

The median amount paid for each beneficiary’s ABPM claims was $52.01 (25th, 75th percentiles: $32.95, $64.98) (Figure 2). Among those with only component ABPM claims, the median amount paid for a beneficiary’s ABPM claims was $30.46 (25th, 75th percentiles: $16.87, $44.05) compared with $55.14 (25th, 75th percentiles: $44.93, $66.37) for a claim for the full procedure. Among reimbursed claims for the full ABPM procedure, those submitted with versus without a WCH diagnosis had a $6.22 (95% CI: $5.06, $7.39) higher reimbursement. Rural beneficiaries had a $5.67 (95% CI: $4.88, $6.47) lower reimbursement amount compared to urban beneficiaries (Supplemental Table 3). Average reimbursement amounts differed by less than $5 across levels of the other characteristics examined. After multivariable adjustment, full ABPM procedure claims submitted with a WCH diagnosis and by institutional providers received higher reimbursements, while rural beneficiaries received lower reimbursements than urban beneficiaries.

Figure 2. Amount reimbursed for an ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) claim, by beneficiary and by Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) procedure code.

Statistics do not include unreimbursed ABPM claims.

Boxes show 25th and 75th percentiles of ABPM claim reimbursement amounts. Solid lines in boxes show the median reimbursement amounts. Dotted lines show mean reimbursement amounts. Whiskers show 10th and 90th percentiles of ABPM claim reimbursement amounts.

“Full procedure” claims were obtained from HCPCS 93784, defined as “ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; including recording, scanning analysis, interpretation and report.”

“Procedure recording” claims were obtained from HCPCS 93786, defined as “ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; recording only.”

“Scan, analysis and report” claims were obtained from HCPCS 93788, defined as “ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; scanning analysis with report.”

“Physician review and report” claims were obtained from HCPCS 93790, defined as “ABPM, utilizing a system such as magnetic tape and/or computer disk, for 24 hours or longer; physician review with interpretation and report.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that ABPM procedures performed in Medicare beneficiaries are likely to be reimbursed by CMS if the ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 is included in the claim. We also found that almost 30% of claims without a 796.2 diagnosis code were reimbursed. Among claims without a 796.2 diagnosis code, claims for procedure components versus for the full ABPM procedure and those submitted by an institutional provider versus a non-intuitional provider were more than twice as likely to be reimbursed. The median reimbursement amount for an ABPM procedure was less than $60.

Medicare ABPM claim processing instructions define suspected WCH as having (1) at least three visits with an office BP >140/90 mm Hg, (2) at least two documented SBP/DBP measurements taken out of the office which are <140/90 mm Hg, and (3) no evidence of end-organ damage [10]. To indicate that ABPM was performed due to suspected WCH, Medicare instructs that an ABPM claim should list the ICD-9 code of 796.2 for a diagnosis of an “elevated blood pressure reading without diagnosis of hypertension”. We found that over 90% of ABPM claims with the ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 were reimbursed. However, in the current study, 62% of beneficiaries with this diagnosis code on their ABPM claim were taking antihypertensive medications. Additionally, adjusted models indicated that claims were reimbursed at a similar rate for beneficiaries taking and not taking antihypertensive medication. While several publications defined WCH as a condition that occurs only in untreated patients [4, 11], prior research indicates that it is also valuable to determine the presence of a white coat effect in treated patients [12–14]. Based on the results of the current study, Medicare does not appear to mandate that the ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 should be restricted to patients who are not on antihypertensive medications.

It is not clear why almost 30% of ABPM claims without an ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 were reimbursed. We found that essential hypertension diagnosis codes were common on both reimbursed and unreimbursed ABPM claims without the 796.2 diagnosis code. Among beneficiaries with an ABPM claim that did not contain a WCH diagnosis code, those submitted by institutional providers were more likely to be reimbursed. This finding is consistent with results of prior studies that have shown that larger, urban healthcare providers that are part of hospital systems are more likely to have extensive documentation processes, including health information technology systems and documentation improvement programs [15–17], that may lead to the submission of more complete claims with a higher likelihood of reimbursement [18, 19]. We did not have access to the supporting documentation for ABPM claims and, therefore, could not assess whether the completeness of documentation was a determinant of success in receiving reimbursement.

Low reimbursement amounts for ABPM in Medicare beneficiaries may discourage healthcare providers from purchasing an ABPM device and performing ABPM. The mean reimbursement for an ABPM procedure in the current analysis is lower than the average of $74 (95% CI: $72, $76) reported in a previous analysis of Medicare data [20]. Even this higher reimbursement amount does not approach the cost of the procedure [14]. ABPM procedures were reported to have provider costs of AU$133 to AU$140 (US$125 to US$131) in Australia [21], and £326 (US$559) in Britain [22], These low reimbursement amounts may discourage providers from performing ABPM. However, both the 2013 European Society of Hypertension Position Paper on ABPM and the 2011 British National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) hypertension management guideline synthesized the literature and concluded that ABPM provides a cost-effective approach for guiding the diagnosis of hypertension [6, 23].

Limited indications for ABPM reimbursement by Medicare may also discourage providers from performing a procedure. Suspected WCH is the only covered indication, and Medicare instructs providers that the need for repeated ABPM procedures should be “rare” [10]. However, repeated ABPM procedures carried out over time may be useful to guide the treatment of hypertension, since the white coat effect and prevalence of WCH increase with age [23–26]. Importantly, repeated ABPM measures may be used to separate true and white coat treatment-resistant hypertension, to identify the development of sustained hypertension among those with diagnosed WCH [27, 28], and to guide antihypertensive therapy to achieve target blood pressures while avoiding overtreatment [14, 23, 29]. In addition to WCH, ABPM accurately identifies masked hypertension, defined as the presence of elevated out-of-office despite non-elevated clinic BP. Masked hypertension has been shown to be associated with a cardiovascular risk similar to that of sustained hypertension [30]. ABPM also has the unique ability to identify a number of abnormal circadian BP patterns associated with increased cardiovascular risk (e.g., elevated nighttime BP, a non-dipping pattern, and an increased morning surge) [23].

Our study has several strengths. We used national data on US adults 65 years of age and older from Medicare. The national reach of Medicare provides high generalizability of our study results to older US adults. Since the size of the white coat effect may increase as patients age [24, 26], adopting the widespread use of ABPM holds even more importance among Medicare beneficiaries. Our study also has limitations. As with all claims-based analyses, our results depend on the accuracy of claims to identify comorbid conditions and pharmacy fills. In addition, given the restricted conditions for which Medicare reimburses an ABPM procedure, many providers may perform ABPM procedures without submitting a claim.

Conclusions

The vast majority of ABPM procedures for Medicare beneficiaries with suspected WCH are reimbursed if the ICD-9 diagnosis code of 796.2 is included on the claim. However, reimbursement amounts are generally below the cost of the procedure. Given low reimbursement amounts and limited indications, coverage may be insufficient to encourage the widespread use of ABPM for identifying WCH and monitoring treated hypertension. These issues may be barriers to performing ABPM in Medicare. Educating providers on CMS instructions for reimbursement of ABPM and evaluation of the reimbursement amounts for ABPM by CMS may increase its appropriate use in older US adults.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Only 68% of Medicare claims for ambulatory blood pressure are reimbursed.

Claims are likely to be reimbursed if the ICD-9 diagnosis code 796.2 is included.

Less than 30% of claims without a 796.2 diagnosis code were reimbursed.

The median reimbursement amount for an ABPM procedure was $52.01.

Acknowledgements

The study was partially supported by T32HL007457, P01HL047540 and P01HL047540-19S1 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The funding source had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Dr. Shia Kent received salary support for Amgen Inc. Dr. Anthony Viera has served on the Medical Advisory Board for Suntech Medical as well as a Hypertension Advisory Board for Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Meredith Kilgore and Dr. Paul Muntner received institutional grants from Amgen Inc. Dr. Muntner also served on an advisory board for Amgen Inc.

Abbreviations

- ABPM

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

- BP

Blood pressure

- CI

Confidence intervals

- CMS

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services

- HCPCS

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision

- JNC

Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure

- US

United States

- WCH

White coat hypertension

Appendix 1. Medicare claims algorithms used to define beneficiary comorbidities

History of diabetes mellitus [31]

Any one of the following:

At least 1 inpatient claim with discharge ICD-9 diagnoses (any position) of 250.xx, 357.2, 362.0×, or 366.41

At least 2 carrier claim, carrier line or outpatient claims with ICD-9 diagnoses (any position) of 250.xx, 357.2, 362.0×, or 366.41, linked by CLAIM_ID to an ambulatory physician evaluation and management claim, with the 2 claims occurring at least 7 days apart

At least 1 prescription record for an oral antidiabetes medication or insulin fills

History of coronary heart disease [32]

Any one of the following:

myocardial infarction: ≥1 inpatient or physician evaluation or management outpatient claims containing ICD-9 diagnoses 410.x or 412.x

revascularization: ≥1 inpatient or outpatient claim containing ICD-9 procedure codes 00.66, 36.01–36.09 or 36.10–36.19, or CPT codes 92980–92996, 33510–33536, or ≥1 inpatient or outpatient claim containing ICD-9 diagnosis codes V45.81 or V45.82

Other ischemic disease: ≥1 inpatient or physician evaluation or management outpatient claim with 411, 413, or 414 codes.

History of stroke [33]

Any one of the following:

At least 1 inpatient ICD-9 diagnosis (any position) of 430.xx, 431.xx, 433.x1, 434.x1 or 436.x

At least 1 carrier claim, carrier line or outpatient claims with ICD-9 diagnoses (any position) of 430.xx, 431.xx, 433.x1, 434.x1 or 436.x, linked by CLAIM_ID to an ambulatory physician evaluation and management claim

At least 1 claim with ICD-9 diagnoses (any position) of 430.xx, 431.xx, 433.x1, 434.x1 or 436.x in other file types (home health aide, durable medical equipment, hospice, skilled nursing facility)

History of chronic kidney disease [34]

Any one of the following:

at least 1 inpatient claim with discharge ICD-9 kidney disease diagnoses: 016.0, 095.4, 189.0, 189.9, 223.0, 236.91, 250.4, 271.4, 274.1, 283.11, 403.xx, 404.xx, 440.1, 442.1, 447.3, 572.4, 580.xx–588.xx, 591, 642.1, 646.2, 753.12–753.17, 753.19, 753.2, 794.4

at least 2 carrier claim, carrier line or outpatient claims with kidney disease ICD-9 diagnoses above (any position), with the 2 claims occurring at least 7 days apart.

History of heart failure [32]

At least one inpatient or outpatient, or carrier line or claim (any position) linked by CLAIM_ID to an ambulatory physician evaluation and management claim with ICD-9 diagnoses of 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.11, 404.91, 404.03, 404.13, 404.93, 428.0, 428.1, 428.20, 428.21, 428.22, 428.23, 428.30, 428.31, 428.32, 428.33, 428.40, 428.41, 428.42, 428.43, or 428.9

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: There are no other potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Shia T. Kent, Email: shia@uab.edu.

Daichi Shimbo, Email: ds2231@cumc.columbia.edu.

Lei Huang, Email: leihuang@uab.edu.

Keith M. Diaz, Email: kd2442@cumc.columbia.edu.

Anthony J. Viera, Email: anthony_viera@med.unc.edu.

Meredith Kilgore, Email: mkilgore@uab.edu.

Suzanne Oparil, Email: soparil@uab.edu.

Paul Muntner, Email: pmuntner@uab.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.James PA, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickering TG, et al. Call to action on use and reimbursement for home blood pressure monitoring: a joint scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American Society Of Hypertension, and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Hypertension. 2008;52(1):10–29. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.189010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2368–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra060433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickering TG, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111(5):697–716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154900.76284.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of secondary screening modalities for hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 2013;18(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e32835d0fd3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause T, et al. Management of hypertension: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;343:d4891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tunis S, et al. [cited 2013 November 23];Decision Memo for Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (CAG- 00067N) 2001 Available from: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=5&NcaName=Ambulatory+Blood+Pressure+Monitoring&ver=9&from=%252527lmrpstate%252527&contractor=22&name=CIGNA+Government+Services+(05535)+-+Carrier&letter_range=4&bc=gCAAAAAAIAAA&.

- 8.Chobanian AV, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ResDAC. [May 29, 2014];Find a CMS file. Available from: http://www.resdac.org/cms-data/search?f%5B0%5D=im_field_privacy_level%3A42.

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [cited 2014 June 20, 2014];National Coverage Determination (NCD) for Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (20.19) 2003 Mar 28; 2003 Available from: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=254&ncdver=2&NCAId=6&ver=4&NcaName=Ambulatory+Blood+Pressure+Monitoring+(1st+Recon)&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&.

- 11.Franklin SS, et al. Significance of white-coat hypertension in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: a meta-analysis using the International Database on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes population. Hypertension. 2012;59(3):564–571. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stergiou GS, et al. Prognosis of white-coat and masked hypertension: International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome. Hypertension. 2014;63(4):675–682. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal R, Weir MR. Treated hypertension and the white coat phenomenon: Office readings are inadequate measures of efficacy. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2013;7(3):236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickering TG, et al. When and how to use self (home) and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4(2):56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford EW, et al. Hospital IT adoption strategies associated with implementation success: implications for achieving meaningful use. J Healthc Manag. 2010;55(3):175–188. discussion 188–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diana ML, et al. Hospital characteristics related to the intention to apply for meaningful use incentive payments. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2012;9:1h. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha AK, et al. Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1628–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0900592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larch SM. Three payer strategies to increase revenue. J Med Pract Manage. 2012;27(5):268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Malley KJ, et al. Measuring diagnoses: ICD code accuracy. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 Pt 2):1620–1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krakoff LR. Cost-effectiveness of ambulatory blood pressure: a reanalysis. Hypertension. 2006;47(1):29–34. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000197195.84725.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewald B, Pekarsky B. Cost analysis of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in initiating antihypertensive drug treatment in Australian general practice. Med J Aust. 2002;176(12):580–583. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorgelly P, et al. Is ambulatory blood pressure monitoring cost-effective in the routine surveillance of treated hypertensive patients in primary care? Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(495):794–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Brien E, et al. European Society of Hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31(9):1731–1768. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328363e964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa J, et al. Age and the difference between awake ambulatory blood pressure and office blood pressure: a meta-analysis. Blood Press Monit. 2011;16(4):159–167. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e328346d603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alwan H, et al. Epidemiology of masked and white-coat hypertension: the family-based SKIPOGH study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yavuz BB, et al. White coat effect and its clinical implications in the elderly. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2009;31(4):306–315. doi: 10.1080/10641960802621341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vongpatanasin W. Resistant hypertension: a review of diagnosis and management. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2216–2224. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muxfeldt ES, et al. Appropriate time interval to repeat ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in patients with white-coat resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):384–389. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.185405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staessen JA, et al. Antihypertensive treatment based on conventional or ambulatory blood pressure measurement. A randomized controlled trial. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring and Treatment of Hypertension Investigators. JAMA. 1997;278(13):1065–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peacock J, et al. Unmasking masked hypertension: prevalence, clinical implications, diagnosis, correlates and future directions. J Hum Hypertens. 2014 doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the Department of Veterans Affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 2):B10–B21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [September 17, 2013];Chronic conditions data warehouse codition categories. Available from: https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories.

- 33.Graham DJ, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and death in elderly Medicare patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone. JAMA. 2010;304(4):411–418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Renal Data System Coordinating Center. USRDS 2012 Researcher’s Guide to the USRDS Database. 2012:39. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.