Abstract

Background:

The Functional Movement Screen (FMS) is a tool that is commonly used to predict the occurrence of injury. Previous studies have shown that a score of 14 or less (with a maximum possible score of 21) successfully predicted future injury occurrence in athletes. No studies have looked at the use of the FMS to predict injuries in hockey players.

Objective:

To see if injury in major junior hockey players can be predicted by a preseason FMS.

Methods:

A convenience sample of 20 hockey players was scored on the FMS prior to the start of the hockey season. Injuries and number of man-games lost for each injury were documented over the course of the season.

Results:

The mean FMS score was 14.7+/−2.58. Those with an FMS score of ≤14 were not more likely to sustain an injury as determined by the Fisher’s exact test (one-tailed, P = 0.32).

Conclusion:

This study did not support the notion that lower FMS scores predict injury in major junior hockey players.

Keywords: screen, movement, hockey, injury, chiropractic

Abstract

Historique :

L’évaluation du mouvement fonctionnel (EMF) est un outil qui est couramment utilisé pour prévoir les blessures. Des études antérieures ont montré qu’une note de 14 ou moins (avec une note maximale possible de 21) réussit à prévoir les blessures futures chez les athlètes. Aucune étude n’a examiné le recours à l’EMF pour prévoir les blessures chez les joueurs de hockey.

Objectif :

Déterminer s’il est possible de prévoir les blessures chez les joueurs de la ligue de hockey junior majeur par une EMF avant le début de la saison.

Méthodologie :

Un échantillon de commodité de 20 joueurs de hockey a été évalué par l’EMF avant le début de la saison de hockey. Les blessures et le nombre de joueurs perdus par jeu pour chaque blessure ont été enregistrés pendant la saison.

Résultats :

La note moyenne d’EMF était 14,7+/−2,58. Ceux qui ont obtenu une note d’EMF ≤14 n’étaient pas plus susceptibles de subir une blessure, telle que déterminée par la méthode exacte de Fisher (unilatérale, P = 0,32).

Conclusion :

Cette étude n’appuie pas l’idée que les notes d’EMF permettent de prévoir les blessures chez les joueurs de la ligue de hockey junior majeur.

Keywords: évaluation, mouvement, hockey, blessure, chiropratique

Introduction

Participation in sports often results in traumatic and overuse injuries.1,2 It has been estimated that 50 to 80% of these injuries are overuse in nature and affect the lower extremity.3 Although, the risk of musculoskeletal injury is multifactorial4–10, recently there has been increased recognition of muscular imbalances, poor neuromuscular control and core instability as potential risk factors for athletic injury11,12. It has also been demonstrated that previous injury is a prominent risk factor for future injuries.13 Kiesel et al.14 hypothesize that complex changes in motor control may result from injury which may be detected using movement oriented tests that challenge a multitude of systems at once. One of these assessment tools is the Functional Movement Screen (FMS).

The FMS is an assessment tool whose utilization has increased in popularity in recent years.15 Its low cost, simplicity of administration and non-invasive qualities contribute to its use by organizations of professional and amateur athletes, military personnel and firefighters.16 According to Cook et al.17 the FMS bridges the gap between pre-participation medical examination and performance evaluation by testing the athletes’ ability to perform functional multi-segmental movements. To perform the FMS, an assessor observes the subject perform seven fundamental movements in order to identify abnormal movement patterns. The assessor gives a score from zero to three based on the quality of movement. The FMS is intended to challenge stability and mobility and requires controlled neuromuscular execution.17 It is thought that muscle imbalances can result in compensatory movement patterns, resulting in poor biomechanics and eventually a micro or macro injury.17

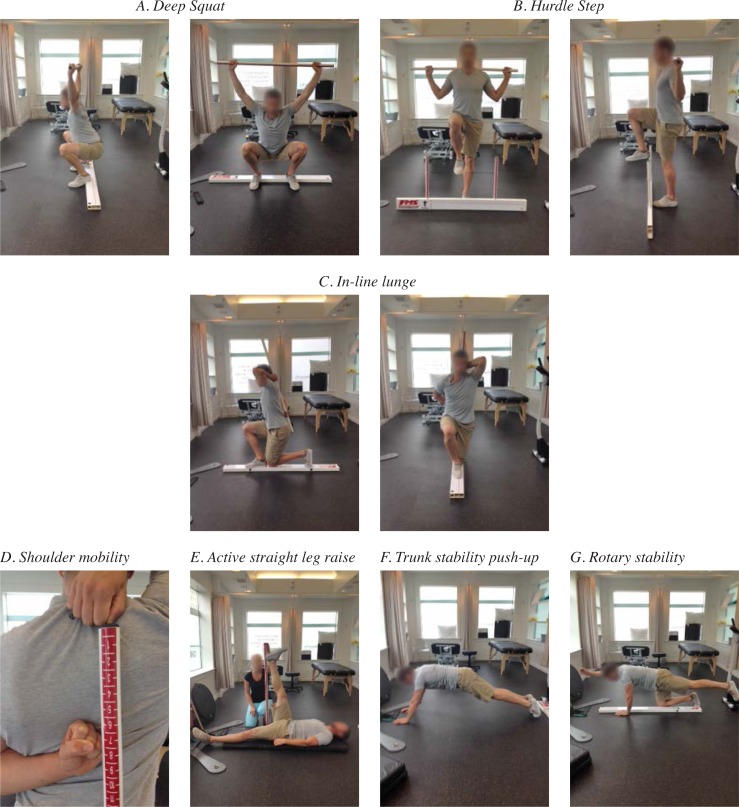

Figure 1 includes pictures for each of the seven sub-tests which comprise the FMS. The seven tests are: 1) the deep squat which assesses functional mobility of the hips, knees and ankles, 2) the hurdle step which examines stride mechanics, 3) the in-line lunge which assesses mobility and stability of the hip and trunk, quadriceps flexibility and ankle and knee stability, 4) shoulder mobility which assesses range of motion and scapular stability, 5) the active straight leg raise which assesses posterior chain flexibility, 6) trunk stability push-up, and 7) the rotary stability test which assesses multi-plane trunk stability.17,18

Figure 1.

Functional Movement Screen Tests

Few studies have investigated the use of the FMS to predict injury in athletes.11,12,19,20 Kiesel et al.19 demonstrated using an receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve that a score of 14 or less on the FMS was associated with an 11-fold increase injury risk when they examined the relationship between FMS scores of 46 professional football athletes and the incidence of serious injury (injury lasting three or more weeks in duration).12 They concluded that poor fundamental movement is a risk factor for injury in football players and that players with dysfunctional movement patterns, as measured by the FMS, are more likely to suffer an injury than those scoring higher on the FMS. Chorba et al.12 found that a score of 14 or less on the FMS resulted in an approximate 4 fold increase in the risk of lower extremity injuries in female collegiate soccer, volleyball and basketball athletes. It was concluded that compensatory movement patterns in female collegiate athletes can increase the risk of injury and that these patterns can be identified by using the FMS. O’Connor et al.21 looked at a population of US Marines and found that a score less than or equal to 14 on the FMS demonstrated a limited ability to predict all traumatic or overuse musculoskeletal injuries (sensitivity: 0.45, specificity: 0.71), while the same cut-off value was able to predict injuries lasting more than three weeks in duration (sensitivity: 0.12, specificity: 0.94). Butler et al.22 examined whether low FMS scores are predictive of injury in firefighters. Similar to Kiesel et al.19, an ROC curve analysis illustrated that an FMS score of ≤14 discriminated between those at a greater risk for injury and those who were not.

If low FMS scores can predict injury, off-season conditioning might be used to restore dysfunctional mechanics to reduce risk. Kiesel et al.14 found that 52% of players on a professional football team were able to improve their score from below to above the established threshold score for injury risk (≤14) in a seven week off-season conditioning program.14 Similarly, Peate et al.11 determined that firefighters enrolled in an eight week program to enhance functional movement reduced time lost to injury by 62% when compared with historical injury rates.

No studies to date have assessed FMS scores as a predictor of injury in hockey players. The purpose of this study is to see if injury in major junior hockey players can be predicted by a pre-season FMS. It is hypothesized that athletes with an FMS score below 14 will have an increased number of injuries compared to those with a score of 14 or above.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

In this cohort study, athletes from a major junior hockey team were assessed during the pre-season using the FMS, and injury incidence was documented over the course of the season. Subjects were invited to participate via email by their team’s head athletic therapist one month prior to the pre-season medical evaluations. Players who were below the age of eighteen were required to obtain approval from a parent or guardian. All members of the team who attended the pre-season medical evaluation chose to participate in the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and ethical approval was received from the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College Ethics Review Board prior to performing the study.

Data collection

FMS data was collected at the team’s practice facility. The lead investigator, a chiropractor who is certified in FMS, performed the screen on each player individually. The administration procedures and scoring were consistent with the standardized version of the FMS test that was developed by Cook et al.17,18 Each player was given three trials on each of the seven sub-tests and received a score from zero to three on each. Scoring criteria were as follows: 0) pain was reported during the movement; 1) failure to complete the movement or loss of balance during the movement; 2) completion of the movement with compensation; and 3) performance of the movement without any compensation. For each sub-test, the highest score from the three trials was recorded. For the sub-tests that were assessed bilaterally, the lowest score was used. Three of the sub-tests (shoulder mobility, trunk stability push-up and rotary stability) also have associated clearing exams that are scored as either positive or negative with a positive response indicating that pain was reproduced during the examination. Should there have been a positive result on a clearing sub-test; the score for that movement would be zero regardless of how well the subject could perform the movement. An overall composite FMS score with a maximum value of 21 was then calculated and participants were informed of their score. No attempt was made to alter the training routine of the players as a result of the FMS score obtained. Only the lead investigator had access to the FMS scores so as to not influence the player’s level of hockey participation.

Injury data was collected from game one up to the end of the last game of the 2013–2014 play-offs for a total of 76 games. Over the course of the season, all injuries were brought to the attention of the team physician who provided a diagnosis for the injury. An injured player returned to hockey once the team physician provided clearance to play. The team’s head athletic therapist recorded all injuries that occurred while playing in a hockey game or practice including the diagnosis, number of man games lost for each injury and whether the injury was from contact or non-contact. For the purpose of this study, injury was defined as a physical condition which occurred during a game or practice which resulted in the player missing at least one game. A contact injury was a subcategory of injury involving collisions with another body, ice or boards and/or contact with puck or stick. Non-contact injuries were all other injuries that did not fall into the contact category.

Data analysis

To maintain consistency with previous studies, a cut-off score of 14 on the FMS was used to assess differences in injury risk.12,19 A 2 x 2 contingency table (Table 2) was created whereby the FMS score was split into groups less than or equal to 14 and more than 14 and the cohort was divided into groups who sustained an injury and those who did not. Sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, disease prevalence, positive predictive value and negative predictive value with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Due to the intermediate sample size two different tests of association were performed: a Chi squared coefficient (Yates corrected) and a Fisher’s exact test with a one-tailed p value of <0.05.

Table 2.

2x2 contingency table for all subjects (N = 20).

| FMS Score | Injured | Not Injured |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 14 | 5 | 3 |

| ≥ 15 | 5 | 7 |

Results

A total of 31 male subjects were assessed using the FMS. Players were excluded from the study if they were traded to another team during the season or did not make the team following training camp. As a result, 20 subjects (ages 16–20) with a mean height and weight of 72 inches and 186lbs respectively were included in the study. Subject FMS scores are presented in Table 1. The mean FMS score and standard deviation (SD) for all subjects (n =20) was 14.7+/−2.58 (maximum score of 21). The mean FMS score for subjects who sustained an injury was 15.0 (+/− 2.21) and for those who were not injured was 14.4 +/− 2.99 respectively. Of the individuals who had an FMS composite score of ≤ 14 (n = 8), 62.5 % sustained an injury over the course of the season while 60.0% of subjects who scored ≤ 13 and 50.0% of subjects who scored ≤ 15 sustained injuries.

Table 1.

Subject FMS scores

| Athlete | Age (years) | FMS score (Max: 21) |

|---|---|---|

| A | 19 | 17 |

| B | 16 | 16 |

| C | 17 | 17 |

| D | 17 | 14 |

| E | 17 | 13 |

| F | 16 | 12 |

| G | 17 | 15 |

| H | 18 | 7 |

| I | 18 | 15 |

| J | 18 | 17 |

| K | 17 | 13 |

| L | 18 | 15 |

| M | 20 | 16 |

| N | 20 | 17 |

| O | 20 | 16 |

| P | 20 | 14 |

| Q | 19 | 12 |

| R | 18 | 15 |

| S | 19 | 19 |

| T | 20 | 14 |

A total of 114 man-games lost were recorded during the season. Of those, 44 were associated with subjects with an FMS score of ≤14 compared to 70 associated with a score of ≥15 (Table 3). Seventeen injuries were recorded during the season, seven occurred in subjects with an FMS score of ≤14 and ten in subjects with an FMS score of ≥14 (Table 3). All of the injuries were a result of contact and no injuries were the result of non-contact.

Table 3.

Nature of Injuries and Number of Man-games lost

| FMS Score | Contact | Non-contact | Man-games lost |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 14 | 7 | 0 | 44 |

| ≥ 15 | 10 | 0 | 70 |

Our results demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.5 (CI95 = 0.189 to 0.811); specificity of 0.7 (CI95 = 0.348 to 0.930); positive likelihood ratio of 1.67 (CI95 = 0.54 to 5.17); negative likelihood ratio 0.71 (CI95 = 0.34 to 1.50); Positive predictive value of 62.50% (CI95 = 0.25 to 0.91) and negative predictive value of 58.33% (CI95 = 0.28 to 0.85). There were no significant differences found in injury incidence between the two FMS score groups using the Fisher’s exact test (one-tailed, P = 0.32). Chi square test of association produced a value of 0.2.

Discussion

The results of this study do not support the hypothesis that low FMS scores (≤14) in hockey players predict the risk of incurring injuries over the course of a hockey season. A lower score on the FMS was not significantly associated with injury. There are several considerations regarding our operational definitions of injury which may have influenced our results. Previous studies have varied in terms of their definition of injury. Kiesel et al.19 defined an injury as three or more weeks of time loss from football. Chorba et al.12 defined an injury that met the following criteria: 1) the injury occurred as a result of participation in an organized practice or competition setting; 2) the injury required medical attention or the athlete sought advice from a certified athletic trainer, athletic training student, or physician. We chose to define an injury as one or more man games lost. It was believed by the authors that inability to play was the least ambiguous definition of injury severity as it had a clear impact to both player and team.

In this study, injuries were categorized as either contact or non-contact because the developers of FMS have hypothesized that repetitive microtrauma caused by aberrant movement patterns, predisposes athletes to overuse type musculoskeletal injury.17,18 Kiesel et al.19 did not define the nature of injuries sustained by the athletes in their study, whereas Chorba at al.12 and O’Connor et al.21 both specified if the injury was from trauma or overuse. We hoped that differentiating these injuries would improve our data interpretation.

All recorded injuries in this study were from contact. Injuries from slashing, collisions, hits, puck impact are unlikely to be affected by better functional movement of an athlete and therefore it is questionable if any of these particular athletes could have avoided injury. The lack of non-contact injuries in this study makes it impossible to compare risk of these injuries between the two groups. Our experience has shown us that, in fact, hockey players do experience non-contact injuries including repetitive strain injuries and while repetitive strain injuries may cause players to miss games, often they will not. From this perspective, our inclusion criteria of missing at least one game may have resulted in these injuries being excluded from our data. Nonetheless, the pattern of injuries recorded in this study illustrates that a majority of man-games lost in hockey are due to contact. It is therefore possible that in sports, like hockey, where collision, stick, and puck injuries are high that the FMS may have less utility in predicting risk.

There are several weaknesses with this study. The relatively short duration of this study limits our ability to see if the potential effects of cumulative microtrauma may eventually lead to pain or injury significant enough to cause a player to miss games. Although all subjects were wearing loose fitting clothing, (shorts and t-shirt) not all were wearing training shoes as they were not specifically instructed to do so prior to arriving for the FMS. As a result, the few participants that did not have training shoes performed the FMS barefoot. This may have produced a lower FMS score for these individuals as they may have had less foot and ankle stability barefoot. Inability to control hydration levels, prior sleep and nutrition at the time of screening reduced our ability to standardize testing conditions. This study did not account for player positions or ice time. We suspect that players with more ice time would have an increased likelihood of being injured. It has been shown that FMS scores are higher in individuals who are more physically mature.24 Our study did not take physical maturity into account. This study used a relatively small sample based on convenience, limiting the statistical strength of our data.

To enhance experimental robustness, future studies should involve more teams and players. We would also suggest that those studies be more longitudinal in design. Age should be considered in data analysis if widely disparate age groups are being studied. Categorizing injuries as either contact or non-contact will continue to assist in determining whether FMS may be more useful for certain types of injuries. Overuse injuries such as tendinopathies are more prevalent in populations of increased age23 and therefore, it is recommended that future research regarding repetitive strain may benefit by studying adult populations.

Conclusion

The results of this study do not support the notion that, when applied to junior hockey players, FMS can identify athletes who are more likely to suffer an in-season injury. Therefore, the FMS cannot be recommended as a pre-season screening tool for injury prevention in this population. Further study is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Colby Treliving for his assistance in this study.

References

- 1.Frohn A, Heijne A, Kowalski J, Svensson P, Myklebus G. A nine-test screening battery for athletes: a reliability study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22:306–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engebretsen A, Myklebust G, Holme I, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Prevention of injuries among male soccer players. A prospective randomized intervention study targeting players with previous injuries or reduced function. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1052–1060. doi: 10.1177/0363546508314432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teyhen D, Shaffer S, Lorenson C, Halfpap J, Donofry D, Walker M, Dugan J, Childs J. The Functional movement screen: A reliability study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(6):530–540. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emery C, Rose M, McAllister J, Meeuwisse W. A prevention strategy to reduce the incidence of injury in high school basketball: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17:17–24. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31802e9c05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hale S, Hertel J, Olmsted-Kramer L. The effect of a 4-week comprehensive rehabilitation program on postural control and lower extremity function in individuals with chronic ankle instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:303–311. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holm I, Fosdahl M, Friis A, Risberg M, Myklebust G, Steen H. Effect of neuromuscular training on proprioception, balance, muscle strength, and lower limb function in female team handball players. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14:88–94. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandelbaum B, Silvers H, Watanabe D, et al. Effectiveness of a neuromuscular and proprioceptive training program in preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1003–1010. doi: 10.1177/0363546504272261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myer G, Ford K, Brent J, Hewett T. The effects of plyometric vs. dynamic stabilization and balance training on power, balance, and landing force in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:345–353. doi: 10.1519/R-17955.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myer G, Ford K, McLean S, Hewett T. The effects of plyometric versus dynamic stabilization and balance training on lower extremity biomechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:445–455. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myer GD, Ford KR, Palumbo JP, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:51–60. doi: 10.1519/13643.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peate W, Bates G, Lunda K, Francis S, Bellamy K. Core strength: a new model for injury prediction and prevention. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2007;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chorba R, Chorba D, Bouillon L, Overmyer C, Landis J. Use of a functional movement screening tool to determine injury risk in female collegiate athletes. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010;5:47–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turbeville SD, Cowan LD, Owen WL, Asal NR, Anderson MA. Risk factors for injury in high school football players. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:974–980. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310063801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiesel K, Plisky P, Butler R. Functional movement test scores improve following a standardized off-season intervention program in professional football players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21:287–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry F, Koehle M. Normative date for the functional movement screen in middle-aged adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:458–462. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182576fa6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raleigh M, McFadden D, Deuster P, Davis J, Knapik J, Pappas C, O’Connor F. Functional movement screening: A novel tool for injury risk stratification of war fighters. proceedings of poster sessions, Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians Annual Meeting; 2010; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook G, Burton L, Hogenboom B. The use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function – part 1. North American J Sports Physical Therapy. 2006;1:62–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook G, Burton L, Hogenboom B. Pre-participation screening: The use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function – Part 2. North Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2006;1:132–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiesel K, Plisky P, Voight M. Can serious injury in professional football be predicted by a preseason functional movement screen? North Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2007;2:147–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burton L. Performance and injury predictability during firefighter candidate training. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; 2006. Unpublished dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor F, Deuster P, Davis J, Pappas C, Knapik J. Functional movement screening: predicting injuries in officer candidates. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:2224–2230. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318223522d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler RJ, Contreras M, Burton L, Plisky P, Goode A, Kiesel K. Modifiable risk factors predict injuries in firefighters during training academies. Work. 2013;46:11–17. doi: 10.3233/WOR-121545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudzki J, Alder R, Warren R, Kadrmas W, Verma N, Pearle A, Lyman S, Fealy S. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound characterization of the vascularity of the rotator cuff tendon: Age and activity related changes in the intact asymptomatic rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1):96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paszkewicz J, McCarty C, Van Lunen B. Comparison of functional and static evaluation tools among adolescent athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:2842–2850. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182815770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]