Abstract

Introduction:

With over 200 million amateur players worldwide, soccer is one of the most popular and internationally recognized sports today. By understanding how and why soccer injuries occur we hope to reduce prevalent injuries amongst elite soccer athletes.

Methods:

Via a prospective cohort, we examined both male and female soccer players eligible to train with the Ontario Soccer Association provincial program between the ages of 13 to 17 during the period of October 10, 2008 and April 20, 2012. Data collection occurred during all player exposures to potential injury. Exposures occurred at the Soccer Centre, Ontario Training grounds and various other venues on multiple playing surfaces.

Results:

A total number of 733 injuries were recorded. Muscle strain, pull or tightness was responsible for 45.6% of all injuries and ranked as the most prevalent injury.

Discussion:

As anticipated, the highest injury reported was muscular strain, which warrants more suitable preventive programs aimed at strengthening and properly warming up the players’ muscles.

Keywords: soccer, injury, athlete, muscle strain

Abstract

Introduction :

Avec plus de 200 millions de joueurs amateurs dans le monde, le soccer est aujourd’hui l’un des sports les plus populaires et internationalement reconnus. En comprenant comment et pourquoi se produisent les blessures dans le soccer, nous espérons réduire les blessures répandues parmi ses athlètes d’élite.

Méthodologie :

Du 10 octobre 2008 au 20 avril 2012, nous avons étudié une cohorte prospective de joueurs et de joueuses de soccer de 13 à 17 ans qui s’entraînaient dans le cadre du programme provincial de l’Ontario Soccer Association. Nous avons recueilli des données à toutes les occasions de risques de blessures pour les joueurs, à savoir au Centre de soccer, sur les terrains d’entraînement de l’Ontario et divers autres lieux sur différentes surfaces de jeu.

Résultats :

On a enregistré un total de 733 blessures. Le claquage ou la raideur musculaire comptait pour 45,6 % de toutes les blessures et se classait parmi la blessure la plus répandue.

Discussion :

Comme prévu, la blessure la plus fréquemment signalée était le claquage musculaire. Pour l’éviter, il faut mettre sur pied des programmes de prévention plus appropriés visant au renforcement et à l’échauffement adéquat des muscles des joueurs.

Keywords: soccer, blessure, athlète, claquage musculaire, chiropratique

Introduction

Participation in sports is considered to be a vital component in achieving an active and healthy lifestyle. With over 200 million amateur soccer players and approximately 200,000 professional athletes worldwide, soccer is one of the most popular and internationally recognized sports played today.1 The 2010 Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup was one of the most watched television events in history. TV broadcasters transmitted the event to a cumulative 26 billion people, with over 400 million views per match.2 As of 2006 there were approximately 270 million active player memberships to FIFA.3 With such a vast number of participants worldwide the concern of safety becomes an important and timely issue. Sports injuries are inevitable, but as with any sport the more vigorous, extensive and frequent the training the greater the potential for injury. As reported by Schmikli et al. the incidence rate of outdoor soccer injuries, particularly for adult male soccer players, is among the highest of all sports including rugby, boxing, fencing, and cricket.4 Although there is some variation as to the exact number of injuries per 1,000 playing hours, according to Goncalves et al. the incidence of soccer related injuries is estimated to be 10 to 15 injuries per 1,000 hours of practice. Furthermore, Haruhito et al. found that in competition there is an incidence of injury of 16.6 to 34.8 injuries per 1,000 playing hours. Injury avoidance is crucial for elite soccer athletes of all competitive levels. It allows them to train and develop their skill sets at their maximal effort without unnecessary layoffs. Time loss due to injury is critical for both a promising soccer athlete and their team due to injury limiting the possibility of the team reaching its highest performance potential. There is an estimated time loss due to injury of two weeks for a team made up of 25 players.5

Moreover, with injury comes an associated economic cost. The immediate health care costs as well as the long term-consequences of being injured are substantial. FIFA estimates that the average treatment cost is 150 U.S. dollars per injury, which leads to an estimated 30 billion dollars a year for treatment of injuries in soccer around the world.6 Also, English Premier League clubs were estimated to be 19 to 26 million U.S. dollars out-of-pocket in lost wages due to the extra injuries suffered by their players in the 2010/11 season after taking part in this summer’s World Cup.7

Consequently, it is evident that injury prevention plays a necessary role in reducing the costs incurred from soccer related injuries as well as minimizing a player’s time loss due to injury. Prevention is the first step in maintaining optimal health, and as such to prevent injury we must understand what types of injuries are commonplace for soccer athletes and how they occurred. The consensus is that the majority of soccer injuries are related to the lower extremities, which is not surprising since soccer is a high-intensity sport characterized by continuous changes of direction and high-load actions.8 Nonetheless, it has been noted in various soccer nations, such as the United Kingdom, the United States and Brazil, the epidemiology of injuries within the sport has shown a variation in injury patterns. For instance, the Carling et al study suggests strains to the hamstring region are the most common type of injury at the professional levels in soccer.9 It has been shown though that eccentric strength training can reduce the risk of hamstring injury in heterogeneous populations of soccer players.10 In addition, plyometric training and agility drills, the main components of a preventive program developed by Heidt et al, was effective in lowering the incidence of injuries in soccer.11 The Dick et al. study concludes ankle ligament sprains, knee internal derangements and concussions are common injuries in women’s soccer, where as Ekstrand et al. determined that almost one third of all injuries in professional soccer are muscle injuries with the vast majority affecting the hamstring, adductors, quadriceps and calf muscles.5,12 According to Aaltonen et al. a decreased risk of sports injuries was associated with the use of insoles, external joint supports, and multi-intervention training programs.13 A paper by Emery and Meeuwisse found that an implemented training program was effective in reducing the risk of all injuries as well as acute-onset of injuries.14 The protective effect of the neuromuscular training program in reducing lower extremity injury is extremely clinically relevant. Finally, Junge and Dvorak showed that there is some evidence that multi-modal intervention programs result in a general reduction in injuries. They found that external ankle supports and proprioceptive/coordination training, especially in athletes with previous ankle sprains, could prevent ankle sprains. In addition, training of neuromuscular and proprioceptive performance as well as improvement of jumping and landing technique seems to decrease the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes.15

The inconsistency of the studies mentioned demonstrates that there are many factors (i.e. location, weather, surface playing field, age, sex and performance level) that ultimately determine the variation on why and how soccer players are injured and in turn, the preventative strategies that can be utilized to help reduce both the occurrence and reoccurrence of such injuries. Therefore, it will be difficult to correlate injury incidence and thus injury prevention for elite soccer athletes outside the geographic domain in which the study was conducted. To date such a study has not been conducted within the scope of elite soccer athletes in Canada.

By taking into consideration the model for epidemiological studies on professional soccer player injuries in Brazil, the purpose of this preliminary study is to provide an injury incidence report for elite soccer athletes in both Ontario as well as nationally in Canada.1 As such, due to differences in climate, technical level and total hours we believe that occurrence of injury per 1,000 hours will be less in Canada compared to other soccer nations. The second objective is to provide an incidence report for the most common injuries during training and matchplay among elite youth soccer players in Ontario. By understanding how and why soccer injuries occur we ultimately hope to reduce the most prevalent injuries amongst elite Canadian soccer athletes.

Research design and methods

In concordance with Goncalves et al. (2011) the research design selected for this study is a prospective cohort. Historically, epidemiologic studies examining soccer injury incidence have been prospective in nature. Previous methodology utilizing retrospective study design had many biases, which reduced the validity of risk assessments. Prospective study design has been shown to be the most useful method for estimating the risk of injury or disease, the incidence rate and or relative risk.

Through a prospective concurrent longitudinal study we can determine and define the population at the beginning of the study and follow the subjects through time. Non-cases are enrolled from a well-defined population, current exposure status is determined as non-injured and the onset of injury is observed in subjects over time. Injury status can be compared to non-injured status relative to exposure time. The study begins at the same time as the first determination of exposure status of the cohort. The characteristics of the group of people studied have been pre-determined as healthy eligible Ontario Soccer Association (OSA) provincial and National Training Centre Ontario (NTCO) players. Non-cases or non-injured eligible players are followed forward in time. Exposure status has been predetermined as all strength and conditioning sessions, training sessions and games over-seen by an athletic therapist. Cases or injury status and recording of the aforementioned have also been pre-determined.

The population of this study included all soccer players, male and female, eligible to train with the Ontario Soccer Association provincial program between the ages of 13 to 17 years during the period of October 10, 2008 and April 20, 2012. It also included all players eligible to play for the National Training Centre Ontario Under-17 women’s program between the aforementioned period. The players were selected based on selection criteria determined by the Ontario Soccer Association Coaches and are considered among the elite population of soccer players in the province and country. In total, the study followed seven teams with 28 players per team through four calendar seasons. The total exposure hours were calculated combining training, match and strength conditioning hours for one calendar year or the provincial program from mid-October until the end of April. The exposure hours were then extrapolated over four years due to the consistency in scheduling within the provincial program related to limitations in field time. A total of 32,270 hours of exposure were recorded over one calendar year and estimated as 129,080 hours over four years.

Collection of data

The source of data collection is The Sports Injury & Rehabilitation Centre, Inc. (SIRC) located at 7601 Martin-grove Rd. Woodbridge, Ontario. The clinic director of operations is Dr. Robert Gringmuth. The staff and associates overseen by Dr. Gringmuth at SIRC are contracted to provide medical coverage for the Ontario Soccer Association Provincial program and Women’s National Training Centre Ontario Program. All player injuries are tracked on site along with patient intakes they are recorded in the clinics patient database called Injury Tracker®.

Data collection occurred during all player exposures to potential injury including strength and conditioning sessions, training sessions and matches. Exposures occurred at the Soccer Centre, Ontario Training grounds and various other venues on multiple playing surfaces. An athletic therapist employed by SIRC oversaw all exposures. Injury reports (Appendix I & II) are filled out by athletic therapists at occurrence of injury and before a player is referred to the clinic if necessary. An injury report is required to be completed if any of the following criteria are met:

Player is removed from field of play by athletic therapist or player is unable to return to play.

Player requires treatment to return to play.

Player suffers a concussion.

Player does not participate in practice due to injury/condition.

Player intake at the clinic directly due to inability to play.

Injury Reports are submitted at the end of the session by the athletic therapists to the clinic supervisor who ensures that a clinic employee enters them into the clinic database.

Ethics and Human Subjects Issues

Players’ names or personal medical information cannot be tracked or identified in any manner. The Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College Research and Ethics Board approved this study.

Results

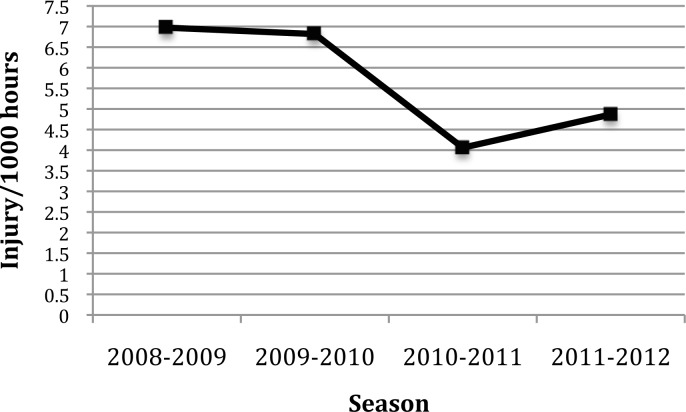

A total number of 733 injuries were recorded through 129,080 exposure hours experienced by the seven teams over the span of four seasons. The cumulative injury incidence rate among all players through four seasons was 5.68 injuries per 1,000 hours of training, strength and conditioning, or matchplay. The highest injury incidence rate per 1,000 hours occurred during the 2008 to 2009 season valued at 6.97 injuries per 1,000 hours. The injury incidence variation seasonally across four years is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Injury incidence of youth provincial and national soccer players in Ontario per 1,000 hours of exposure over four seasons.

Myofascial pain resulting from muscle strain, pull, or tightness was responsible for 45.6% of all injuries. It was ranked as the most prevalent of all diagnosed injuries with an incidence rate of 1.42 occurrences per 1,000 hours. Ligamentous sprain comprised 20.7% of all injuries ranking it the second most common injury presented. Its incidence rate was 0.64 injuries per 1,000 hours. Sprain and strain injuries comprised 66.3% percent of total injuries incurred. Concussion injuries consisted of 4.2% of total injuries and had an incidence rate 0.13 per 1,000 hours. Other common injuries reported include bleeding, lacerations, abrasions, blisters, and fractures. The most prevalent diagnosed injuries and their incidence rates per 1,000 hours are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Incidence of most diagnosed injuries between 2008 to 2012

| n | % | Incidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprains | 83 | 20.7 | 0.64 |

| Muscle strain/pull/tightness | 183 | 45.6 | 1.42 |

| Fractures | 15 | 3.7 | 0.12 |

| Concussions | 17 | 4.2 | 0.13 |

| Blisters | 29 | 7.2 | 0.22 |

| Bleeding/lacerations/abrasions | 35 | 8.7 | 0.27 |

| Separation of joint | 2 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Bunion of the big toe | 4 | 1.0 | 0.03 |

| Common cold | 7 | 1.8 | 0.05 |

| Asthma causing symptoms with participation | 9 | 2.2 | 0.07 |

| Plantar fasciitis | 5 | 1.3 | 0.04 |

| Poked in eye | 2 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Turf toe | 2 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Avulsion fracture | 2 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Achilles tendonitis | 3 | 0.8 | 0.02 |

| Hyperextension of unspecified joint | 1 | 0.3 | 0.01 |

| Joint instability | 2 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| Total | 401 | 100.0 | 3.11 |

The most commonly injured body part across all four years was the ankle/foot complex. It comprised 35.6% of all injuries over four years and had an incidence rate of 2.02 per 1,000 hours. The knee was the second most common across all seasons except in 2008 to 2009, where it interchanged positions with the lower leg complex. The knee comprised 16.4% of total injuries and had a reported incidence rate of 0.93 injuries per 1,000 hours. Injuries of the lower leg complex consisting of the achilles, shin and calve injuries were the third most common injuries. It comprised 12% of total injuries with an injury incidence rate of 0.68. Muscle injuries to the quadriceps, hamstring and groin comprised a combined 16.2% of injuries and had an incidence rate of 0.92 injuries per 1,000 hours. Lower extremity injuries encompass 82% of total injuries and had an incidence rate of 4.7

Discussion

With the ongoing growth of soccer in Canada, risk of injury and avoidance of it can be a deciding factor on how young elite Canadian athletes compare with their peers from competing soccer nations. In order to help determine what the incidence or risk of injury is there are two things that need to be defined: the definition of an injury and the standard measure for reporting soccer related injuries. The term injury in its relation with soccer is currently defined as anything that incapacitates a soccer player from full participation in imminent training or matches.3 Moreover, the standard measure for reporting the incidence of soccer related injuries are determined by how long an individual athlete is exposed to the possibility of an injury, as such the measure is the number of injuries per 1,000 hours of soccer participation (i.e. practice, training, leisure, and game play).1 Our study concluded that the total injury incidence rate over all exposures was 5.68 injuries per 1,000 hours. This rate is far less than what is reported from Ha et al who conducted a 15-year epidemiological study on injuries during official Japanese professional soccer league matches. The study had a comparably high incidence rate ranging from about 11 to 24 injuries per 1,000 hours, but this is significantly higher than a study conducted by Le Gall et al on elite French youth players which has an overall injury rate ranging from 4.6 to 5.3 injuries per 1,000 hours. Similarly, our study figure is comparable to other studies conducted on youth soccer players, which had incidences ranging from 0.535 to 5.640 injuries per 1,000 hours.16 Furthermore, there are comparable findings with common injury sites in which our study along with the participants found in the study by Le Gall et al and a study on elite English academy players had the most prevalent diagnosed injury being injury due to muscle strain, sprain and pull or tightness with 66.34%, 62.5% and 66% respectively.16

The shortcomings of conducting a prospective cohort study include changes in methodology for detecting or recording injury due to the length of study period. In this specific study inter-examiner variability exists between the various athletic therapists. Although they are trained to follow protocol, their interpretation of the injuries can affect reported findings. Exact exposure hours are unattainable, as attendance was not taken during all sessions. Therefore, exposure hours are calculated based on the assumption that all players were present for all training sessions and games, which is not always the case. Exposure hours will most likely be overestimated. In addition, the study did not look at how the exposure time was split between time spent training and time spent during games. By differentiating match play and training we can make conclusions as to whether overtraining may be the cause of injury or if match intensity results in higher injury rates.

The strength of this study includes the sample size of the study, the study period and the elite status of the athletes. Few studies have followed as many elite athletes, over as many exposure hours, at such a high level of competition. Due to the size and methodology of the study, conclusions can be made with sufficient empirical evidence and validity.

Future recommendations for improving data collection/data analysis are to include the following: whether injury was due to contact, foul play or spontaneous occurrence; the time of the injury; player’s position; and prior injuries. Noting how an injury arose can be a useful tool in understanding how to prevent the same injury from reoccurring. With players forcefully colliding for the soccer ball, pushing for positioning during a corner kick and receiving/delivering a tackle or charge, there can be various moments in which a player can get injured due to contact or foul play.12 During the 2002 and 2006 World Cups it was reported that 73% of the injuries occurred during contact play.3

The time of injury can also be a useful tool to use. There have been many studies with various results on when injuries do in fact occur. Hawkins et al reported that there was a difference between the incidence of injury with each 15 minute segment in a game compared to 45 minute halves, whereas Rahnama et al reported that mild injuries occur during the first 15 minute segments of each half and that moderate injuries occur during the last 15 minute segment of the game.3 Dick et al reported that the risk of injury is the highest during the first and last 15 minutes of game play. Since there is no precise time for when injuries occur in soccer matches, further studies should be conducted to determine an estimated time for when Canadian soccer athletes are most likely to sustain injuries.12

Consideration of the player’s position is also a factor that can be analyzed. Was the player injured playing their regular position or a different one due to external circumstances? After discussion with the coach, players usually settle on their particular position for the season, and barring any unforeseen circumstances they stick with that position throughout the season. Moreover, another factor that can be analyzed is which position gets injured more? Elite youth defenders are injured more often than their fellow teammates during competition, where as the injury rate for goalkeepers account for only 6% of all player injuries in adult professional soccer games.16 These results show that the physical demands for each position vary and thus may account for the frequency and also type of injury Canadian soccer players may face.

Lastly, prior injury is a factor that can be used to help improve the analysis of this study. Re-injuries cause 30% longer absence from game play, thus knowing whether there is prior case of injury can help evaluate the risk and scope of training needed.12 A prior injury can increase the risk of future injuries and thus a proper evaluation is needed by teams to determine whether a player is susceptible to a particular injury. In addition, if a player has a history of a specific reoccurring injury, rehab programs can be analyzed to see what can be improved in order to prevent the injury from occurring again.

This study sheds light on the number and varying types of injuries sustained by elite Canadian soccer players, however it fails to address certain issues that need to be looked at in the future, which include injury predictors in soccer, such as behavioural, environmental, and physical. However, some practical applications can be drawn from what was found, such as the fact that muscular strains, pulls and tightness were the most commonly found injury of soccer players. Thus, an appropriate strengthening program and proper implementation of warm-up and cool down exercises before training and matches can potentially help reduce the number of muscular strain occurrences. The occurrence of injuries in high-level soccer players is most likely multifaceted. Volpi and Taioli noted several external, personal, and behavioural risk factors likely associated with injuries, as well as risk factors that can be avoided or prevented through appropriate interventions.17 Over the past years the intensity and speed of both training and game play along with the players’ skill level and experience are hypothesized to be a contributing factor to the type and number of injuries registered.17,18 Another risk factor that has been noted is the ratio of time-spent training to playing in games. Less time available for appropriate training was noted to be a good indicator of injuries in soccer players. A few factors have been identified, but have not been fully addressed to our knowledge, which include environmental factors, such as training and playing surfaces, field conditions at the time of injuries and type of shoes. Another predictor is the amount of time spent playing between players, meaning that in high level teams coaches are more prone to select the best players to play larger number of minutes during a game sometimes overworking these individuals.

All in all, results from the present study on injury rates of elite Canadian soccer youth revealed what was suspected for occurrence over 1000 exposure hours in comparison to major soccer countries. The highest injury reported was muscular strain, which warrants more suited preventative programs aimed at strengthening and properly warming up the players’ muscles. Also, as noted by several other soccer injury studies, the ankle region was the area of highest sustained injuries, justifying the possible need for further prospective intervention studies to evaluate an injury prevention protocol. This study is specifically important to the Canadian Soccer Association, the Ontario Soccer Association and its respective medical providers. Identifying an epidemiological model for injury incidence is important in understanding how injury develops. As such, preventative programs can be designed in the focusing on maintaining the growth and development of amateur and elite Canadian soccer players alike.

Table 2.

Prevalence of injury location and injury incident rate per 1,000 hours

| 2008 to 2009 | 2009 to 2010 | 2010 to 2011 | 2011 to 2012 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Body part | n | % | Incidence | n | % | Incidence | n | % | Incidence | n | % | Incidence |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Ankle/foot | 90 | 40.00 | 2.79 | 84 | 38.7 | 2.60 | 34 | 25.56 | 1.05 | 53 | 33.54 | 1.64 |

| Knee | 23 | 10.22 | 0.71 | 48 | 22.2 | 1.49 | 25 | 18.79 | 0.77 | 24 | 15.19 | 0.74 |

| Quadriceps | 18 | 8.00 | 0.56 | 9 | 4.1 | 0.28 | 12 | 9.02 | 0.37 | 2 | 1.27 | 0.06 |

| Hamstrings | 11 | 4.88 | 0.34 | 6 | 2.6 | 0.19 | 8 | 6.01 | 0.25 | 11 | 6.33 | 0.31 |

| Groin/adductors | 11 | 4.88 | 0.34 | 10 | 4.5 | 0.31 | 14 | 11.00 | 0.43 | 7 | 3.80 | 0.19 |

| Head/face | 11 | 4.88 | 0.34 | 16 | 7.3 | 0.50 | 9 | 7.00 | 0.28 | 14 | 8.86 | 0.43 |

| Neck/back | 9 | 4.00 | 0.28 | 7 | 3.2 | 0.22 | 5 | 4.00 | 0.15 | 7 | 3.80 | 0.19 |

| Shoulder/arm/hand/fingers | 16 | 7.11 | 0.50 | 9 | 4.1 | 0.28 | 2 | 1.50 | 0.06 | 5 | 5.06 | 0.25 |

| Lower leg/achilles/shin/calf | 24 | 10.66 | 0.74 | 24 | 10.1 | 0.74 | 20 | 15.03 | 0.62 | 20 | 13.92 | 0.68 |

| Toes | 11 | 4.88 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2 | 1.27 | 0.06 |

| Hip | 1 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 7 | 3.2 | 0.22 | 2 | 2.00 | 0.06 | 12 | 6.96 | 0.34 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | 225 | 100.00 | 6.97 | 220 | 100.0 | 6.82 | 131 | 99.91 | 4.06 | 157 | 100.00 | 4.90 |

References

- 1.Goncalves CA, Belangero PS, Runco JL, Cohem M. The Brazil Football Association (CBF) model for epidemiological studies on professional soccer player injuries. Clinical Science. 2011;66(10):1707–1712. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011001000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FIFA; Previous FIFA World Cups. Retrieved December 12, 2012 from: http://www.fifa.com/worldcup/archive/index.html.

- 3.Ha A, Ohata N, Kohno T, Tsuguo M, Seki J. A 15-year prospective epidemiological account of acute traumatic injuries during official professional soccer league matches in Japan. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1006–1014. doi: 10.1177/0363546512438695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmikli SL, de Vries WR, Inklaar H, Back FJ. Injury prevention target groups in soccer: Injury characteristics and incidence rates in male junior and senior players. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.10.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekstrand J, Hagglund M, Walden M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in profession football (soccer) Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1226–32. doi: 10.1177/0363546510395879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassabi M, Mortazavi MJ, Giti MR, Hassabi M, Mansournia MA, Shapouran S. Injury profile of a professional soccer team in the Premier League of Iran. Asian J Sports Med. 2010;1(4):201–208. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clubs count the cost of world cup injuries. [ www.lloyds.com]. 2010 [cited 2012 Dec 18] Available from: http://www.lloyds.com/news-and-insight/news-and-features/market-news/specialist-2010/clubs-count-the-cost-of-world-cup-injuries.

- 8.Wong P, Hong Y. Soccer injury in the lower extremities. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:473–82. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.015511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carling C, Gall FL, Orhant E. A four-season prospective study of muscle strain reoccurrences in a professional football club. Res Sports Med. 2011;19:92–102. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2011.556494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnason A, Andersen TE, Holme I, et al. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:40–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidt RS, Jr, Sweeterman LM, Carlonas RL, et al. Avoidance of soccer injuries with preseason conditioning. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:659–62. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick R, Putukian M, Agel J, Evans TA, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women’s soccer injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2002–2003. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):278–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaltonen S, Karjalainen H, Heinonen A, Parkkari J, Kujala UM. Prevention of sports injuries: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(15):1585–1592. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. The effectiveness of a neuromuscular prevention strategy to reduce injuries in youth soccer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(8):555–562. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.074377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Junge A, Dvorak J. Soccer injuries: a review on incidence and prevention. Sports Med. 2004;34(13):929–938. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Gall F, Carlin C, Reily T, Vadewalle H, Church J, Rochcongar P. Incidence of injuries in elite French youth soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):928–38. doi: 10.1177/0363546505283271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volpi P, Taioli E. The health profile of professional soccer players: future opportunities for injury prevention. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(12):3473–3479. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31824e195f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazemi M, Pieter W. Injuries at a Canadian National Taekwondo Championships: a prospective study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2004;5:22–30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]