Abstract

This article examines issues and challenges in the design of cultural adaptations that are developed from an original evidence-based intervention (EBI). Recently emerging multistep frameworks or stage models are examined, as these can systematically guide the development of culturally adapted EBIs. Critical issues are also presented regarding whether and how such adaptations may be conducted, and empirical evidence is presented regarding the effectiveness of such cultural adaptations. Recent evidence suggests that these cultural adaptations are effective when applied with certain subcultural groups, although they are less effective when applied with other subcultural groups. Generally, current evidence regarding the effectiveness of cultural adaptations is promising but mixed. Further research is needed to obtain more definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy and effectiveness of culturally adapted EBIs. Directions for future research and recommendations are presented to guide the development of a new generation of culturally adapted EBIs.

Keywords: cultural adaptation, adaptation models

Overview of Culture and Intervention Adaptations

Clinical psychologists have a deep respect for scientific principles that have contributed to the development of interventions and the substantiation of their effectiveness in relieving human suffering and remediating problems in living. This research tradition has promoted disciplinary standards of evidence for determining that an intervention is efficacious in producing one or more targeted outcomes (Flay et al. 2005). Subsequently, tested-and-effective treatment procedures have been incorporated into treatment manuals and other media to facilitate consistency in treatment delivery (Chambless & Hollon 1998).

From the perspective of clinical practice, clinical psychologists have equal respect for an in-depth understanding of the person and of human variation (Sue & Sue 1999). The essence of the clinical method involves the application of nomothetic principles filtered through an individual case conceptualization and informed by clinical judgment for effectively treating each person. Within this duality, a dynamic tension has emerged between the standardized nomothetic scientific top-down approach that demands fidelity in its implementation and the idiographic casewise bottom-up approach that demands sensitivity and responsiveness to each person's unique needs.

This dynamic tension can foment controversy, raise contentious issues, and launch a search for common ground. The cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions is a specific topic where these two equally important professional values have clashed, particularly as embodied by the fidelity-adaptation dilemma (Castro et al. 2004, Elliott & Mihalic 2004). Within this context, we examine the literature on treatment and prevention interventions; thus, we use the term evidence-based interventions (EBIs) to refer to interventions of two types: (a) those developed to treat existing disorders, usually within clinical settings, i.e., evidence-based treatments (EBTs) and (b) interventions developed for preventing disorders within various at-risk populations, i.e., evidence-based prevention interventions (EBPIs).

The cultural adaptation of EBIs has emerged as an intervention strategy and will likely grow in prominence as a result of two trends (La Roche & Christopher 2008, Lau 2006): (a) the growing demand for EBIs and (b) the growing diversification of the American population. The growing demand for EBIs has emerged despite clinicians' concerns that it may be premature and may impose unrealistic constraints on clinical practice (Bernal & Scharrón-del-Río 2001, Norcross et al. 2006).

Division 12 of the American Psychological Association (APA) has taken a leadership role in establishing criteria for determining that a psychological intervention is evidence based and in maintaining a catalog of interventions that meet these criteria (Am. Psychol. Assoc. 1995, 2006). Other groups, including the National Registry of Evidence-Based Prevention Programs (NREPP) (Schinke et al. 2002), have created such lists (Subst. Abuse Mental Health Serv. Admin. 2009). This demand has also been driven by several professional groups, including clinical researchers and scientist-practitioners who feel a professional responsibility to develop and deliver interventions supported by research evidence. Other advocates include agencies that pay for psychological services and civic, community, and governmental organizations that demand evidence that limited funds will be spent appropriately on interventions that work (Whaley & Davis 2007).

The second trend involves the growing cultural diversity within the United States and the globalization of intervention disseminations (Iwamasa 1997, Weisman et al. 2006). Unfortunately, the infusion of cultural factors into EBIs and tests of their efficacy with subcultural groups have not kept pace with these diversification trends. In this regard, La Roche & Christopher (2008) note that racial/ethnic minority participants have rarely been included in samples used for validating the efficacy of EBIs, including many of those recognized by APA's Division 12 in 1995 (Am. Psychol. Assoc. 1995). This limitation has changed only moderately over the past decade.

Purpose and Scope

The purpose of this review is to provide an analysis of issues and challenges involved in the design of cultural adaptations that are developed from original EBIs. We do so by pursuing two aims. First, we review fundamental approaches and frameworks for a deep structure analysis of culture, as tools for designing cultural adaptations of EBIs. Second, we identify and discuss critical issues and challenges in the design of these cultural adaptations. The analysis of these issues is guided by the following four questions:

Are cultural adaptations developed from original EBIs justifiable?

What procedures should intervention developers follow when conducting a cultural adaptation?

What is the evidence that cultural adaptations are effective?

How can within-group cultural variation be accommodated in a cultural adaptation?

In our analysis, we take a contemporary view of clinical psychology science and practice by including evidence from prevention interventions and from clinical psychotherapies for psychological disorders. We include prevention interventions because they also introduce important issues involving cultural adaptations (Muñoz 1997). Finally, this review presents a summary of what we know about the cultural adaptation of EBIs, examines issues and challenges, and presents suggestions for future research along with a few recommendations.

Perspectives and Challenges in the Design of Cultural Adaptations

Several issues and challenges emerge in developing a cultural adaptation of an EBI. A first challenge involves the conceptualization of culture in the design of an adapted EBI that is tailored to the needs of a particular cultural group. Cultural adaptation involves a planned, organized, iterative, and collaborative process that often includes the participation of persons from the targeted population for whom the adaptation is being developed. The cultural competence of the investigator and of the cultural adaptation team is also important for conducting a deep structure analysis (Resnicow et al. 2000) of the needs and preferences of a targeted cultural group. Resnicow and colleagues (2000) indicate that cultural sensitivity in developing tailored prevention interventions consists of two dimensions: surface structure adaptations and deep structure adaptations. According to Resnicow and colleagues, surface structure adaptations involve changes in an original EBI's materials or activities that address observable and superficial aspects of a target population's culture, such as language, music, foods, clothing, and related observable aspects. By contrast, deep structure adaptations involve changes based on deeper cultural, social, historical, environmental, and psychological factors that influence the health behaviors of members of a targeted population.

Concepts of Culture and Cultural Frameworks

Culture is a complex construct, as indicated by over 100 varied definitions of culture that have been proposed (Baldwin & Lindsley 1994). Fundamentally, culture consists of the world-views and lifeways of a group of people. Muñoz & Mendelson (2005) add that human phenomena can be construed at three conceptual levels: (a) universal characteristics that tend to apply to all people, (b) group-focused characteristics and norms that apply to special cultural groups (or subcultural groups), and (c) individualized characteristics that are unique to the individual person.

A distinct group of people (a tribe, an ethnic group, professional organization, a nation) can be described as “having a culture,” meaning that its members share a collective system of values, beliefs, expectations, and norms, including traditions and customs, as well as sharing established social networks and standards of conduct that define them as a cultural group (Betancourt & Lopez 1993). Their cultural heritage is transmitted from elders to children, and it confers members of this cultural group with a sense of peoplehood, unity, and belonging, a collective identity or ethnicity (McGoldrick & Giordano 1996). Language is a distinct facet of culture that encodes symbols, meanings, forms of problem solving, and adaptations that also facilitate the group's survival (Harwood 1981, Thompson 1969 as cited by Baldwin & Lindsley 1994).

Although culture is a complex construct, it can nonetheless be applied in the design and cultural adaptation of an original EBI. A challenge in this application involves problems that emerge when equating culture with ethnicity and/or when using ethnicity or nationality as proxy variables for culture. Culture and ethnicity are not synonymous (Betancourt & Lopez 1993), and developing a cultural adaptation does not necessarily involve the development of an ethnic adaptation.

Population Segmentation

An emerging challenge in designing a culturally relevant adaptation of an original EBI involves reframing this adaptation under a unit of analysis other than ethnicity. In this regard, population segmentation (Balcazar et al. 1995) narrows an otherwise heterogeneous ethnic population or group into a smaller and more homogeneous subcultural group to avoid ethnic gloss in planning an intervention (Resnicow et al. 2000, Trimble 1995). As an example of this approach, as minority youths are disproportionately overrepresented within juvenile justice settings, being under adjudication can operate as a salient factor that better defines the common life experiences of a certain subcultural group of deviant youths. This subcultural group can consist of youths from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds (African Americans, Latinos, white nonminority) who share several common developmental and familial experiences (i.e., disrupted families, antisocial conduct, and experiences of incarceration or rehabilitation). Thus, their common developmental trajectories can establish this multiethnic group of deviant youths as a subcultural group of adolescent juvenile offenders. This example illustrates how investigators may reframe their perspective on culture by addressing a common cultural identity, such as adjudicated youths, as the cultural unit of analysis for the design of a culturally relevant adaptation, in place of focusing on the label of ethnicity per se.

Subcultural Groups

In the United States there exists considerable heterogeneity within and between major racial/ethnic groups: Latinos/Hispanics, African Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans. These racial/ethnic groups range in population size from about one million among Native Americans to over 42.7 million for Hispanics/Latinos (U.S. Census Bur. News 2006). Within each of these broad racial/ethnic groups, there exist many homogeneous subcultural groups, hidden subpopulations that can be defined by population segmentation (Balcazar et al. 1995). This approach can examine the intersection of cultural elements (Schulz & Mullings 2006) such as nationality, socioeconomic status, religious background, immigration status, gender, and generational group, as well as any special identity or social status, such as being under adjudication. We discuss aspects of this segmentation approach later in this review.

The Structure of Culture as a Collection of Cultural Elements

Chao & Moon (2005) introduced the “cultural mosaic” as a structural framework consisting of a collage of elements that constitute a person's sociocultural identity. The identity of each individual consists of a unique combination of elements (or cultural tiles), including demographic (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, gender), geographic (e.g., urban-rural status, region or country), and associative (e.g., family, religion, profession). As an extension of this framework, an ethnic group consists of a collective of individuals who share many common elements (e.g., a common heritage, religion, or ethnic identity). Accordingly, members of this group share a common group identity, although each individual also differs from the others in his or her unique combination of cultural tiles.

This mosaic may appear complex, yet upon closer inspection it exhibits a coherent and identifiable structure. This integrative systemic approach describes the complexities of culture within its natural ecological context and also captures the perspective of anthropologists Kluckhohn and Murray, who stated that every person is like all other people, some other people, and no other person (Kluckhohn & Murray 1948).

Systemic-Ecological Models of Culture

Erez & Efrat (2004) proposed a multilevel model of culture that features both structural and dynamic elements. Structurally, these levels of culture range from the most macro (global culture) to the most micro (the individual person). An earlier version of this systemic model, Bronfenbrenner's ecodevelopmental model (Bronfenbrenner 1986) introduced the macro, exo, meso, and micro ecological levels. This model describes how events at each of these levels can influence an adolescent's identity development and behaviors. From a dynamic perspective, temporal influences on individual behavior and development can also be examined systemically, e.g., how parents influence a child's development over time. This multilevel model is similar to other more recent systemic ecodevelopmental models that have been proposed (Castro et al. 2009, Szapocznik & Coatsworth 1999). Erez & Efrat (2004) also advocate for a shift from conceptions of culture as a stable entity toward a conception of culture as a dynamic entity that exhibits multiple influences across time and ecological levels.

Cultural Change and Acculturative Adaptation

A major concept in the analysis of culture and cultural change is acculturation. Acculturation is a worldwide phenomenon that occurs when individuals and families migrate from one sociocultural environment to another in quest of better living conditions. Early conceptions of acculturation regarded it as a linear, unidirectional process, although more contemporary frameworks emphasize two dimensions: an orientation to the new host culture (the mainstream culture) and an orientation to the native culture (the ethnic culture) (Oetting & Beauvais 1990–1991). This two-factor conceptualization, however, is not without its criticisms (Rudmin 2003). Under this two-factor framework, variations in acculturative outcomes include a bicultural/bilingual identity (Berry 1994, Cuellar et al. 1995, Marin & Gamboa 1996) as well as complete assimilation into the mainstream culture.

A deep structure understanding of cultural change and adjustment can inform intervention adaptations so that they address issues of acculturation change, as these may increase risk behaviors among some members of a subcultural group. Acculturation stressors in familial and social contexts have been associated with higher rates of substance use (Vega et al. 1998), implicating the erosion of native culture family values, attitudes, and behaviors (Gil et al. 2000, Samaniego & Gonzales 1999). Other studies of acculturative stress among African Americans (Anderson 1991) have also alluded to the erosion of Afrocentric values that may reduce familial protections against substance use.

Cultural Relevance and Cultural Adaptation

To the extent that an EBI lacks relevance to the cultural needs and preferences of a subcultural group (i.e., beliefs, values, customs, traditions, and lifestyles), that intervention may receive unfavorable responses from these participants. When compromised by low participation rates, that EBI will likely exhibit a loss in effectiveness. This intervention phenomenon has prompted the emergence of a principle of cultural relevance (Castro et al. 2004, 2007; Frankish et al. 2007). This principle indicates that an EBI that lacks relevance to the needs and preferences of a subcultural group, even if the intervention could be administered with complete fidelity, would exhibit low levels of effectiveness. This principle also suggests that an intervention developer must develop a deep structure understanding of a subcultural group's culture (Resnicow et al. 2000) in order to develop a culturally relevant and effective EBI.

By contrast, high consumer responsiveness and participation would be expected for an intervention that is high in cultural relevance as characterized by (a) comprehension: understandable content that is matched to the linguistic, educational, and/or developmental needs of the consumer group; (b) motivation: content that is interesting and important to this group; and (c) relevance: content and materials that are applicable to participants' everyday lives (Castro et al. 2004).

Terminology for Approaching Cultural Adaptation

Another challenge is the choice of strategy in the design of a cultural adaptation of an EBI. The concepts and terminology used in planning an adaptation will influence this strategy. Three terms have been used to describe efforts to incorporate culturally relevant content into an intervention: culturally adapted, culturally informed, and culturally attuned. In a lucid commentary, Falicov (2009) described cultural adaptations to EBIs as procedures that maintain fidelity to the core elements of EBIs while also adding certain cultural content to the intervention and/or its methods of engagement. She saw cultural adaptations as a middle ground between two extreme positions: (a) a universal approach that views an original EBI's content as applicable to all subcultural groups and, therefore, not in need of alterations, and (b) a culture-specific approach that emphasizes unique culturally grounded content consisting of the unique values, beliefs, traditions, and practices of a particular subcultural group. From this middle ground, cultural adaptation may draw criticism from both extremes by proposing alterations regarded as deviations from fidelity. Thus, from one perspective, it goes too far; conversely, from the other perspective, it lacks sufficient integrations of cultural perspectives and thus does not go far enough. Falicov (2009) observed that cultural adaptations are based on the premise that

…the core components of a mainstream form of treatment should be replicated faithfully while adding-on certain ethnic features. This assumption must be based on the idea that the core components are culture-free and even more problematically, that the theory of change involved is universally powerful (p. 295).

Bernal and colleagues have defined cultural adaptation as the systematic modification of an EBT (or intervention protocol) to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client's cultural patterns, meanings, and values (Bernal et al. 2009).

The term “culturally informed intervention” might convey a sense that culture is a more primary consideration than it is in cultural adaptations (Falicov 2009), although that distinction is not widely acknowledged. Intervention development studies sometimes favor the term “culturally informed” over “cultural adaptation” (e.g., Santisteban & Mena 2009, Weisman et al. 2006). For example, Culturally Informed Therapy for Schizophrenia, a family-based therapy, was piloted with Latinos living in Miami and added specific modules on key cultural components such as collectivism and spirituality (Weisman et al. 2006). More common topics that might be found in other family-training interventions such as communication and problem solving also were included.

“Cultural attunement” is a term that was coined by Falicov (2009) to refer to additions to evidence-based therapies that are intended to boost engagement and retention of subcultural groups in treatment. This terminology and approach focuses on the process of intervention delivery rather than on intervention content. Providing services in clients' native language, including familiar cultural traditions, and utilizing bicultural staff are examples of features that might attract subcultural groups into treatment and increase their comfort in sustained participation. The additional implication here is that attunement is a surface structure adaptation that does not modify core intervention components that were designed to affect therapeutic change mechanisms or outcomes.

In reality, there exists a continuum among cultural adaptations that varies between the extremes of making no alterations to an original EBI in its application to a subcultural group and the complete rejection of the EBI in favor of a novel, culturally grounded approach that is developed in collaboration with the intended consumers. In between those two extremes are alterations that change few or many of the features of an intervention to affect engagement and/or the intervention's core components that influence mediating mechanisms of change.

Professional Contexts Affecting the Design of Cultural Adaptations

Distinctions Regarding Types of Evidence-Based Interventions

Evidence-based treatment and evidence-based practice

In addition to the noted variation in terminology and approach to intervention adaptation, there are two approaches to the application of research evidence, i.e., evidence-based treatment (EBT) and evidence-based practice (EBP) (Kazdin 2008). EBT refers to the specific interventions or techniques, such as cognitive therapy for depression, that have produced therapeutic change as tested within clinical trials. By contrast, EBP is seen as a broader term that refers to “clinical practice that is informed by evidence about interventions, clinical expertise, and patient needs, values, and preferences and their integration into decision-making about individual care” (Kazdin 2008, p. 147). As in the realm of cultural adaptations, in reality a continuum exists between the extremes of EBT and EBP, and often these boundaries blur. From a somewhat broader perspective, the APA 2005 Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, defined evidence-based practice in psychology (EBPP) as “the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences” (Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2006, p. 273). From this perspective, in addition to empirical research evidence, clinical expertise is also regarded as a viable source of evidence that can guide the development of clinical interventions.

Clinical practice is characterized by the application of clinical experience and judgment to alleviate a specific presenting problem as effectively as possible (Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2006). On a practical level, one ongoing concern involves the extent to which clinicians can and actually do utilize the results of clinical research to guide their clinical interventions. Some clinicians have been skeptical about the clinical applicability of certain EBIs, especially when intervention procedures have been incorporated into a treatment manual (Duncan & Miller 2006).

Evidence-based intervention treatment manuals

Treatment manuals describe an intervention in sufficient detail so that the practitioner can appropriately implement core components in treatment delivery (Addis & Cardemil 2006) and produce targeted treatment outcomes, provided that the treatment is conducted with adherence to the manualized techniques and activities. Despite some criticisms about the reputed rigidity of treatment manuals, well-constructed treatment manuals have been described as not rigid and, to the contrary, afford therapists flexibility and allow discretionary decision making under a series of dialectics that encourage (a) balancing adherence to the treatment manual versus clinical flexibility and (b) balancing attention to the therapeutic relationship versus attention to therapeutic techniques (Addis & Cardemil 2006).

Also, the greater the therapist's experience, the greater the range of flexibility that the therapist can exercise in applying clinical judgment in response to a client's unique needs. The experienced therapist may be seen as conducting a single-case cultural adaptation when tailoring an EBI to the unique needs of a particular racial/ethnic minority client. This flexibility is likely pervasive within daily clinical practice, although it raises questions about the limits of flexibility that a therapist may exercise. How can a therapist tailor the original EBI in response to the unique cultural and treatment needs of any individual minority client while also adhering to an EBI's manualized tested-and-effective therapeutic principles and methods (Addis & Cardemil 2006)? Within this context, examples exist of adaptations of EBIs that were not effective when deviating from core procedures contained in the original EBI (Kumpfer et al. 2002), thus raising concerns about a loss of efficacy when deviating significantly from the established tested-and-effective EBI. Also, when does flexibility in adaptation merge into misadaptation, a haphazard or inappropriate change in the proscribed procedures of a manualized EBI (Castro et al. 2004, Ringwalt et al. 2004)?

Four Major Issues in Cultural Adaptation

The Fidelity-Adaptation Dilemma

Core issues affecting cultural adaptations

A fundamental controversy in this field of adaptations is the fidelity-adaptation dilemma, which consists of a dialectic involving arguments favoring fidelity in the delivery of an EBI as designed versus arguments favoring the need for adaptations to reconcile intervention-consumer mismatches in accord with the needs and preferences of a subcultural group (Bernal & Scharrón-del-Río 2001, Castro et al. 2004, Elliott & Mihalic 2004). There are reasoned arguments on both sides of the fidelity-adaptation issue. On the one hand, intervention researchers spend years developing, refining, and testing the efficacy of a theory-based and structured intervention, thus recommending that it be administered with high fidelity to the intervention procedures as designed. This view is that efficacy is best attained under strict adherence to the intervention's procedures as tested and validated; there should be no compromises (Elliott & Mihalic 2004). By contrast, if an intervention lacks relevance and fit with the needs and preferences of a specific subcultural group (an intervention-consumer mismatch) or within diverse ecological conditions, then certain adaptations are usually necessary.

Castro et al. (2004) developed a table that shows the possible sources of mismatch that can occur between a program validation group and the current consumer group (see Table 1). These specific sources are presented under three domains: (a) group characteristics, (b) program delivery staff, and (c) administrative/community factors. The general adaptation strategy is to identify specific sources of intervention-consumer mismatch and then to introduce specific adaptive elements or activities that resolve each of these sources of mismatches to enhance relevance and fit.

Table 1. Sources of intervention-population mismatch.

| Source of mismatch | Original validation group(s) | Current consumer group | Actual or potential mismatch effect |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Group characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Language | English | Spanish | Consumer inability to understand program content; a major adaptation issue |

| Ethnicity | White, nonminority | Ethnic minority | Conflicts in beliefs, values and/or norms; reactance |

| Socioeconomic status | Middle class | Lower class | Insufficient social resources and culturally different life experiences |

| Urban-rural context | Urban inner city | Rural, reservation | Logistical and environmental barriers affecting participation in program activities |

| Risk factors: number and severity | Few and moderate in severity | Several and high in severity | Insufficient effect on multiple or most severe risk factors |

| Family stability | Stable family systems | Unstable family systems | Limited compliance in program attendance and participation |

|

| |||

| Program delivery staff | |||

|

| |||

| Type of staff | Paid program staff | Lay health workers | Lesser or different program delivery skills and perspectives |

| Staff cultural competence | Culturally competent staff | Culturally insensitive staff | Limited awareness of, or insensitivity to, cultural issues |

| Staff cultural competence | Culturally insensitive staff | Culturally competent staff | Staff will refer to missing cultural elements and criticize the program for being culturally insensitive or unresponsive; misadaptation |

|

| |||

| Administrative/community factors | |||

|

| |||

| Community consultation | Consulted with community in program design and/or administration | Not consulted with community | Absence of community “buy-in,” community resistance or disinterest, and low participation |

| Community readiness | Moderate readiness | Low readiness | Absence of infrastructure and organization to address drug abuse problems and to implement the program |

Source: Castro FG, Barrera M Jr, Martinez CR. 2004. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev. Sci. 5:41–45.

Concerns Over Erosion of Intervention Effectiveness

The distinction between efficacy and effectiveness is central to the aims of cultural adaptation. Whereas efficacy measures how well an intervention works when tested within the controlled conditions under which it was designed, effectiveness measures how well the intervention works in an applied, real-world setting (Flay et al. 2005, Kellam & Langevin 2003). Due to the greater challenges in the application of a tested-and-effective intervention in complex real-world settings, level of effectiveness, as measured by effect size, is almost always smaller relative to efficacy. The challenge involves sustaining the full intervention effects of the validated intervention when transitioning from lab to community. Similarly, this aim of maintaining the full intervention effects is central in the transition from the original EBI to an adapted EBI.

One other consideration regarding intervention efficacy and effectiveness involves the criterion of effectiveness, as defined in reference to a specific population or group. This criterion is that “A statement of efficacy should be of the form that, ‘Program or policy X is efficacious for producing Y outcomes for Z population.’” (Flay et al. 2005, p. 154). In other words, for many interventions, a general statement regarding the “universal effectiveness” of an intervention for all people and outcomes is essentially meaningless. This criterion for effectiveness refers to the external validity of the original EBI and the role of a cultural adaptation, given that the effectiveness of an EBI should be defined in relation to the population (or populations) with which it was tested; effectiveness remains undefined or is indeterminate in relation to a population that is significantly or culturally different from the original validation population.

Issue #1: Are Cultural Adaptations of Evidence-Based Treatments Justifiable?

A history of objections to the 1995 Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures notes that some have viewed this report as reflecting a double standard (Bernal & Scharrón-del-Río 2001). The report appeared to endorse the use and dissemination of EBIs under the premise that adequate support exists regarding their efficacy. Nonetheless, it was apparent that the foundation research had limited external validity owing to the limited inclusion of diverse samples to establish intervention efficacy with these various constituencies. In the absence of sufficient evidence that an EBI is effective for a particular subcultural group, some scholars have argued that cultural adaptations or even novel culturally grounded treatments are justifiable and even necessary.

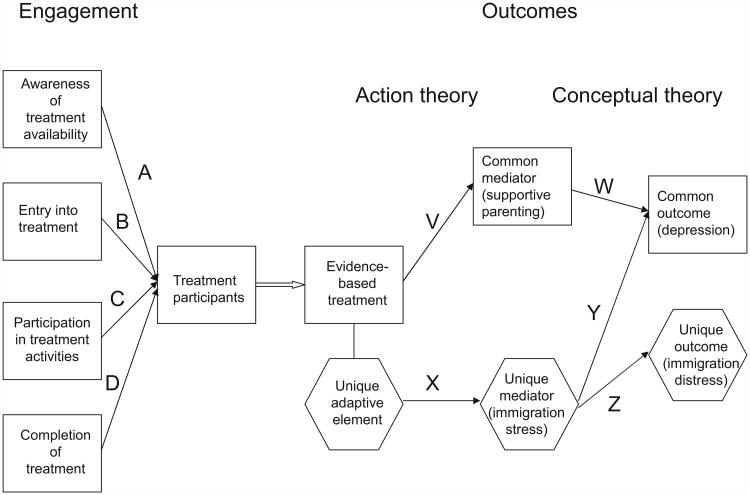

Lau (2006) has provided a thoughtful analysis of the issue of when to develop a cultural adaptation for an EBI. She advocated a theory-and data-driven selective and directed approach for determining whether an EBI should be culturally adapted and, if so, which treatment elements might be altered. In a related approach, Barrera & Castro (2006) developed Figure 1 in their commentary on the Lau (2006) article to illustrate the features of an intervention that might be considered for adaptation. The cultural adaptation of an original EBI is justified under one of four conditions: (a) ineffective clinical engagement, (b) unique risk or resilience factors, (c) unique symptoms of a common disorder, and (d) nonsignificant intervention efficacy for a particular subcultural group.

Ineffective engagement

As shown in Figure 1, during the engagement stage, a first justification for an adaptation is that an intervention exhibits deficiencies in its ability to engage clients from a particular subcultural group relative to rates of engagement found for other groups. The various forms of engagement include (a) awareness of treatment availability, (b) entry or enrollment into treatment, (c) participation in treatment activities, (d) retention and completion of treatment (see Figure 1, paths A, B, C, D). In (e) prevention interventions, this includes active outreach to a targeted group to mobilize their participation. In prevention interventions, attracting and retaining the participation of community residents and/or members of high-risk subcultural groups remains one of the greatest challenges in the design and implementation of efficacious and successful prevention-related EBIs.

Figure 1.

A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions.

Unique risk or resilience factors

A second justification arises when the original EBI shows diminished efficacy because a subcultural group demonstrates unique risk or resilience factors that are related to a clinical outcome. This is tantamount to suggesting that certain subcultural groups exhibit different etiological processes that influence the occurrence and course of a common disorder. Such culturally specific mechanisms would suggest the need to add new and efficacious intervention components that are different from the original core components in order to prevent or change the occurrence and/or severity of a targeted disorder. One hypothetical example is an EBI for childhood depression developed initially for children with no experience with immigration stressors. If evidence for a new subcultural group (e.g., the children of immigrants) suggests that immigration stressors are related to childhood depression, an adaptation of the original EBI that adds a unique adaptive component to buffer the effects of immigration stressors would be justified (see path X in Figure 1).

Research evidence on risk factors can also suggest the modification or deletion of certain core intervention elements or components that do not contribute to improving targeted outcomes. A multistudy project by Yu & Seligman (2002) provided an example of the cultural adaptation of a prevention program for youths in Beijing, China, that modified original core component material on assertiveness in order to accommodate local cultural norms and expectations. These investigators cited research supporting their view that low assertiveness was less of a risk factor for the Chinese children as compared with Western children. Within this Chinese cultural context, culturally assertive interactions of Chinese children with their parents were qualitatively different from the assertive interactions of their Westernized peers with their parents. This cultural context prompted the design of a modified adaptation component that was culturally responsive to these cultural differences involving the form, meaning, and risk potential of low assertiveness.

Unique symptoms of a common disorder

A third situation that justifies cultural adaptations is when a subcultural group shows unique symptoms that are associated with a common disorder (see path Z in Figure 1). Lau (2006) illustrated this condition by describing research that showed that southeast Asian refugees had unique manifestations of panic attacks that were ameliorated when specialized treatment procedures were added (Hinton et al. 2005). The identification of unique risk/resilience factors and unique symptom features can be accomplished by a careful review of basic epidemio-logical research or by new studies (e.g., Yu & Seligman 2002).

Nonsignificant intervention efficacy

A fourth justification for the cultural adaptation of an intervention is provided when an EBI is implemented with fidelity with a subcultural group, yet the quantitative results reveal less-effective outcomes, as indicated by attenuated effect sizes. As one example, an adapted version of a preventive intervention for depression (the Penn Resiliency Program) was tested with Latino and African American youths in Philadelphia (Cardemil et al. 2002). Results showed that the intervention was successful in reducing depression symptoms for Latinos, but the intervention did not affect the hypothesized mediating mechanisms or depression for African American youths. The data indicated that this intervention required additional adaptive elements to be effective with African American children.

An entirely new intervention

A fifth condition that extends well beyond adaptation is a case where an entirely new intervention is proposed. Such an extreme option would be justifiable and necessary when no relevant treatment exists to meet the unique needs of a particular subcultural group. Given the proliferation of scores of treatment and prevention interventions now available, it is difficult to justify the development of an entirely new intervention. A preferable approach would be to identify a closest-fitting EPI for a particular subcultural group and then consider the various aforementioned approaches to cultural adaptation.

The growing need for cultural adaptations

In their conclusions regarding the state of science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities, Miranda and colleagues (2005) indicate that a question that remains unanswered involves the extent to which interventions need to be culturally adapted to be effective with minority populations. This question should be reframed, in part, to accommodate the considerable within-group variation that exists within each of the four major racial/ethnic minority populations of the United States: Latinos/Hispanics, African Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans. When the unit of analysis is the total population of a given ethnic/racial group, e.g., Latinos, the answer to this question depends on the cultural characteristics of the particular targeted subcultural group. For example, among Latinos, the most basic form of cultural adaptation, linguistic adaptation (translation from English to Spanish; Castro et al. 2004), is unnecessary and is not relevant for high-acculturated Latinos, whereas it is absolutely necessary for low-acculturated Latinos. By contrast, beyond this instance of a need for a linguistic adaptation, conducting a more substantive cultural adaptation requires that the interventionist command a deep-structure understanding of the needs and preferences of members of a specific subcultural group to successfully adapt the original EBI in response to these needs and preferences.

Miranda and colleagues (2005) also identified three core issues regarding future efforts to improve the quality and availability of interventions for racial/ethnic minority populations. These issues involve (a) the need to consider cultural context in the delivery of interventions; (b) the need for methodologies that tailor EBIs for specific subcultural groups, including the identification of cultural factors that are amenable to adaptation; and (c) the need for methods that will actively engage ethnic minorities in interventions, including outreach to these populations and ways to deliver interventions on a larger scale (Miranda et al. 2005).

Finally, a recent Institute of Medicine report on prioritizing comparative-effectiveness research (Iglehart 2009) identified two prominent need areas: (a) understanding the operation of health care delivery systems, and (b) understanding the effects of racial and ethnic disparities on health. Within these areas, improving the delivery of EBIs within health systems and enhancing EBI effectiveness for reducing health disparities via cultural adaptations serve as relevant and important research and practice goals.

In summary, the applicability of an EBI to a particular subcultural group can be ascertained from a reasoned analysis of engagement factors, the theoretical models of unique and common risk factors, and the targeted outcome variables. An analysis of these factors can serve as the initial stage of a planned, structured, and collaborative process for culturally adapting an original EBI.

Issue #2: What Procedures Should Intervention Developers Follow When Conducting a Cultural Adaptation?

Stage models are prominent in the development and testing of new drugs, medical procedures, and psychosocial interventions (Rounsaville et al. 2001). Several stage models also have been proposed for the cultural adaptation of EBIs, and these introduce considerations that differ from those that guide the development of new interventions. Table 2 summarizes three models and suggests how they converge and diverge in content, comprehensiveness, and scope. A critical aspect of these models is that they contain deliberate steps that guide intervention developers in using qualitative and quantitative data to determine the need for a cultural adaptation, the elements of the intervention that might be changed, and estimates of the effects of intervention alterations.

Table 2. Comparison of adaptation process models.

| Kumpfer et al. (2008) | McKleroy et al. (2006) | Wingood & DiClemente (2008) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

|

|

|

These comprehensive stage models of cultural adaptations are illustrated with specific interventions: the Strengthening Families Program (Kumpfer et al. 2008) and HIV/AIDS prevention (McKleroy et al. 2006, Wingood & DiClemente 2008). The comprehensiveness of those models is understandable because these stages were intended for the national and international dissemination of the core interventions. Activities such as assessing agency capacity and staff selection are indicative of the models' grounding in the practicalities of broad-scale dissemination. A recent article describing the ADAPT-ITT model is particularly valuable because it contains specific descriptions of methods, including marketing research strategies that can be used at each stage (Wingood & DiClemente 2008). The ADAPT-ITT model was illustrated with applications to African American women in Atlanta and Zulu-speaking adolescent women in Africa. This model, which grew out of a public health tradition, has considerable relevance for applications to more mainstream clinical psychology topics.

A simplified framework by Barrera & Castro (2006) contains the essential elements of comprehensive adaptation models. It presents four stages, consisting of (a) information gathering (review the literature to understand common and unique risk factors and conduct focus groups to assess perceived positives and negatives of the original EBI), (b) preliminary adaptation design (develop recruitment strategies and modify the intervention based on information gathered in step a), (c) preliminary adaptation tests (pilot test the modified recruitment, intervention, and assessment procedures), and (d) adaptation refinement (modify the intervention based on pilot results and subject the intervention to a full evaluation with quantitative and qualitative data) to evaluate the efficacy of the adapted intervention.

This model was used in the adaptation of a lifestyle intervention for adult Latinas who had diabetes (Barrera et al. 2010). The pilot testing stage served as the most valuable step in the adaptation process, particularly because it contained mechanisms for ongoing feedback from participants and intervention staff members. Similar stages were developed independently of the Barrera & Castro (2006) framework and illustrated in the adaptation of a depression preventive intervention for Latino families (D'Angelo et al. 2009).

Other models contain steps that are subsumed by models shown in Table 2. Domenech Rodríguez & Wieling (2004) drew from Rogers's (2000) framework on the diffusion of innovations to propose a three-phase Cultural Adaptation Process Model. That model includes the steps of (a) studying the relevant literature, establishing a collaborative relationship with community leaders, gathering information from community members on needs and interests; (b) drafting a revision of the intervention, soliciting input from community members, and pilot testing; and (c) integrating the lessons learned from the preceding phase into a revised intervention that could be used and studied more broadly. These strategies include both bottom-up and top-down approaches; thus, like those in the other process models, they strike “a balance between community needs and scientific integrity” (p. 320).

These conceptual frameworks describe the processes that intervention developers can follow in designing, implementing, and evaluating a culturally adapted EBI. Others have provided guidance in identifying the intervention content that might be adapted. Hwang (2006) offered a psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework and illustrated it with considerations that were made in adapting a cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for Asian American clients. The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework contains six general domains and 25 therapeutic principles that were organized within those domains. The domains consist of aspects of the entire psychotherapy enterprise that therapists should be aware of when treating clients from subcultural groups: (a) dynamic issues and cultural complexities, (b) orientation of clients to therapy, (c) cultural beliefs, (d) client-therapist relationship, (e) cultural differences in expression and communication, and (f) cultural issues of salience (e.g., shame and stigma, acculturative stress).

Bernal et al. (1995) presented a framework that contains eight dimensions that can be the subject of culturally sensitive interventions: (a) language of the intervention, (b) similarity and differences between the client and therapist, (c) cultural expressions and sayings that might be used in treatment, (d) cultural knowledge, (e) treatment concepts, (f) goals, (g) treatment methods, and (h) context of the treatment (e.g., developmental stage, phase of migration, acculturative stress). In summary, these somewhat overlapping frameworks regarding the content of treatment interventions implemented within clinical settings complement other models that describe the steps in conducting a cultural adaptation.

Thus, criticisms that there exist no frameworks for guiding the cultural adaptation of interventions are no longer valid. It is clear that significant advancements have been made in establishing systematic, data-driven, consumer-sensitive processes for determining if EBIs should be adapted, how they should be adapted, and what the results of those adaptations are on engagement and intervention outcomes. Some of the published exemplars of those approaches report only on results from pilot data with very small samples that offer encouraging results (e.g., Barrera et al. 2010, D'Angelo et al. 2009, Matos et al. 2006), although larger-scale outcome studies will appear soon. It will be interesting to determine if cultural adaptations that were developed through such comprehensive, multistep processes will exhibit higher levels of effectiveness, as compared with earlier adaptations that were conducted before such process frameworks appeared in the literature. A related question is whether the adapted EBI, when compared with the original EBI, can offer value-added effects by exhibiting significantly better outcomes, including significantly larger effect sizes on targeted outcome variables.

Issue #3: Is There Evidence that Cultural Adaptations are Effective?

At the present time, the best answer to the question regarding the effectiveness of cultural adaptations has been provided in a meta-analytic review by Griner & Smith (2006). They reviewed 76 published and unpublished studies that contained explicit statements that intervention content, format, or delivery was adapted, “based on culture, ethnicity, or race.” The review produced several important findings:

Half of the studies used two to four types of adaptation activities; 43% used five or more. The most common adaptation activities (84% of studies) involved the inclusion of cultural values and concepts. This was followed by native language matching of clients to therapists (74%), ethnic group matching of clients to therapists (61%), and treatment in clinics that explicitly served clients from diverse cultural backgrounds (41%).

The weighted average effect size was d = 0.45, which indicated that culturally adapted interventions were moderately effective.

Interventions provided to groups of same-race participants (d = 0.49), were four times more effective than interventions provided to groups consisting of mixed-race participants (d = 0.12).

Studies that explicitly described interventions in which therapists spoke the same non-English language as clients had a higher effect size (d = 0.49), as compared with studies that did not describe language matching (d = 0.21).

For studies that included Latino participants, average effect sizes from studies of low-acculturated Latinos (mostly Spanish-speaking clients) were twice as large as the average effect sizes from studies in which the Latino participants exhibited moderate levels of acculturation (bilingual/bicultural clients). Although the authors' confidence in this observation was attenuated by the small number of studies, they interpreted this pattern as suggestive evidence that low-acculturation participants are in greater need of a cultural adaptation and stand to benefit more.

Adapted interventions with younger participants produced somewhat smaller effect sizes than did adapted interventions with older participants.

This review provided suggestive evidence that culturally adapted interventions are effective. Some findings pointed to the possibility that clients who had the greatest need for accommodations (i.e., low-acculturated, non-English-speaking adults) received the greatest benefit from such adaptations. Future research studies that are explicitly designed to evaluate particular intervention components and features may clarify if these components operate as new core components that enhance targeted intervention outcomes. The studies included in this review were completed before 2005. Since that time, several journal special issues (Bernal 2006, Bernal & Domenech Rodríguez 2009) and other noteworthy studies have been published that have added further support to the conclusion that culturally adapted interventions are effective.

By contrast, Huey & Polo (2008) conducted a detailed review that, unlike Griner & Smith (2006), was restricted to just EBIs and research that involved ethnic minority children and adolescents. However, these investigators reached a much less positive conclusion than did Griner & Smith (2006) about the evidence supporting cultural adaptations. For example, one argument in favor of cultural adaptations is that EBIs are relatively ineffective for ethnic minority clients. Huey & Polo (2008) reported that 5 of the 13 studies that tested for treatment-by-ethnicity interactions found evidence of differential treatment efficacy. Three studies found that the EBIs were more effective for ethnic minority children when compared with white children, whereas two studies found the opposite pattern.

Huey & Polo (2008) also looked for evidence that culturally responsive EBIs enhanced treatment outcomes. They contrasted the effect sizes from studies that were identified as culturally responsive with those that were not. A conservative definition resulted in 10 studies that used culturally responsive treatments and 10 that used standard treatments. A more liberal definition resulted in the classification of 14 treatments as culturally responsive and 6 as standard. Neither the conservative nor liberal classification methods resulted in significant differences in effect sizes when culturally responsive treatments were compared to standard treatments with ethnic minority children. However, the authors acknowledged the lack of statistical power for making such comparisons. Also, as Griner & Smith (2006) noted, the need for culturally adapted treatments might be lower for children than for adults. Overall, on the basis of the studies they reviewed, Huey & Polo (2008) concluded that the “utility of cultural adaptation remains ambiguous” (p. 293) and warrants more research.

In summary, evidence from these two meta-analytic studies is mixed regarding the efficacy of culturally adapted EBIs relative to the original EBI and regarding their effectiveness in general. Is the glass half empty or half full? One way to interpret these results is to indicate that current evidence shows the pervasiveness of cultural adaptations that have been developed from original EBIs. These adaptations are typically effective in general. They are often, but not always, as effective as the original EBI and usually exhibit greater relevance to the needs of a targeted subcultural group.

Issue #4: How Can Wide Within-Group Cultural Variation Be Accommodated in a Cultural Adaptation?

It is ironic that cultural adaptations intended to correct the one-size-fits-all application of EBIs by creating an ethnic adaptation that applies to most members of a given ethnic group can be subjected to the criticism that they too do not adequately respond to the heterogeneity that exists within that cultural group. Within a large population, such as within the United States, a given ethnic minority group, e.g., Latinos, consists of many individuals who differ broadly from each other on dimensions of acculturation and other cultural factors. How might a cultural adaptation be effective for such a diverse population? One noted approach involves population segmentation (Balcazar et al. 1995), a variation of market segmentation (Lefevre & Flora 1988), that consists of identifying a smaller and more homogeneous subpopulation (or subcultural group) whose members have common needs and preferences that are more effectively addressed with a focused cultural adaptation that is tailored to this subcultural group's collective needs and preferences.

Another solution to this problem rests with intervention procedures that contain standardized decision rules for varying the content and “dosage” of treatment, depending on the characteristics of particular sectors of participants or groups, e.g., families. This is the essence of adaptive intervention designs (Collins et al. 2004). The word “adaptive” is unavoidably awkward in the context of this discussion about culturally adapted EBIs. In most outcome research studies, investigators seek to provide the same treatment contents in the same number of sessions to all of the participants who are assigned to an intervention condition. This approach emulates the rigors of experimental research designs, albeit at the expense of sensitivity to within-group individual variations in clinical and cultural needs and preferences. In contrast, adaptive interventions are closer in form to individualized clinical practice because they provide explicit guidelines for the delivery of different dosages of intervention components depending on the unique needs of individual clients and based on evidence-based decision rules for determining variations in these dosages. Such specific decision rules would also allow replicability in clinical practice and research, such that well-crafted decision rules could be developed to respond appropriately to the common needs of a well-specified group of clients.

Collins et al. (2004) provide examples from the well-known Fast Track project to illustrate how an adaptive intervention might be used with children who vary in their need for academic, behavior management, and family support components of the intervention. Such adaptive approaches hold considerable promise in general, and particularly for cultural adaptations that would be applied with specific and somewhat heterogeneous subcultural groups. The broad dissemination and application of such adaptive intervention designs would require the availability of a sufficiently large actuarial database that is drawn from a diverse set of populations, from which evidence-based rules can then be developed and ultimately applied to a wide cross-section of clients. A related issue involves the cultural competence of the intervention developers and of the intervention delivery staff. Cultural competence would be essential in developing culturally appropriate decision rules from the accumulated actuarial evidence.

In the same spirit of adaptive interventions, Piña et al. (2009) has described a “culturally prescriptive intervention framework” that guides the tailoring of childhood anxiety interventions depending on the cultural features of the individual or family. Rather than applying a fixed set of adaptation activities, their treatment manual describes a uniform set of guidelines to assist interventionists in determining how to attend to language and other cultural considerations (e.g., familism) in tailoring the intervention. The Piña et al. (2009) study also illustrates how their childhood anxiety treatment adaptation incorporates the eight cultural parameters described by Bernal et al. (1995) and the initial treatment development stage described by Rounsaville et al. (2001). This approach is realistic and actively addresses the conflict between fidelity and fit.

In summary, one feasible goal in the design of culturally adapted EBIs is to utilize population segmentation to identify a more narrowly defined subcultural group, thus reducing the within-group variability that exists within a large ethnic population. A second strategy is to develop adaptive intervention protocols that are tailored to the individual's or subcultural group's unique needs and preferences. Ideally, both segmentation and adaptive intervention approaches can be used strategically to enhance the intervention-consumer fit and the resulting intervention effectiveness.

Applying Cultural Adaptation Approaches

Exemplars of Culturally Grounded Cognitive-Behavioral Treatments

CBT approaches in the treatment of adult depression are among the most heavily researched EBIs (Butler et al. 2006). Muñoz and colleagues at the Depression Clinic of San Francisco General Hospital have conducted a number of studies on the cultural adaptation of CBT for adult depression treatment and prevention (e.g., Kohn et al. 2002, Miranda et al. 2003, Muñoz & Mendelson 2005). Muñoz & Mendelson (2005) describe how these interventions were built on the core principles of social learning theory (behavioral activation, social skills, and cognitive restructuring) and then were modified to be culturally sensitive through five considerations: (a) ethnic minority involvement in intervention development, (b) cultural values, (c) religion and spirituality, (d) acculturation, and (e) racism, prejudice, and discrimination. These manualized interventions have been used broadly with a variety of ethnic/racial groups by a number of different investigative teams in the United States and abroad, and through a variety of media.

Two studies conducted with CBT depression treatment have special relevance for this article. One was a small quasi-experimental study that compared African American women (n = 10) who received the standard CBT group therapy through the Depression Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital with those who elected to participate in a group designed specifically for African American women (n = 8) (Kohn et al. 2002). The adaptation added four modules concerned with healthy relationships, spirituality, African American family issues, and African American female identity. Although formal statistical analyses were not performed, women in the standard treatment showed a 5.9 prepost drop in Beck Depression Inventory scores, whereas women in the culturally adapted group showed a 12.6 point drop. In our estimation, this was one of only three studies that have compared a cultural adaptation to a standard intervention (Botvin et al. 1994, Kohn et al. 2002, Szapocznik et al. 1986) and the only one that has shown any suggestive evidence of the extra benefits from the cultural adaptation. The possibility of additional benefits from adaptations to an intervention that was already modified to be culturally sensitive was an encouraging outcome of this study. One limitation is the lack of statistical analyses, although that dovetails with the small sample size. Other limitations can include design issues that also center around these two aspects of a small study.

A second study (Miranda et al. 2003) consisted of a randomized trial that contrasted the CBT group therapy (n = 103) developed by Muñoz and his colleagues with the same group therapy regimen supplemented with telephone outreach case management, i.e., CBT with supplemental case management (n = 96). Of the 199 predominantly low-income participants, 77 were Spanish speaking, 46 were African American, and 18 were Asian or American Indian. Case managers worked with patients on “problems in housing, employment, recreation, and relationships with family and friends” (Miranda et al. 2003, p. 220). Results showed that patients who received supplemental case management were less likely to drop out of treatment and attended more treatment sessions as compared with patients who received just the CBT group therapy. For Spanish-speaking patients, those who received supplemental case management reported fewer depressive symptoms at the end of treatment than did those who received CBT groups only.

The addition of the supplemental case management component was prompted by the socioeconomic hardships and daily stressors observed among members of this subcultural group and not by any particular cultural aspect of race or ethnicity. Nevertheless, this study illustrates how a supplemental adaptation designed to increase participant engagement to a culturally sensitive treatment could produce enhanced beneficial outcomes. It also illustrates the importance of cultural competence among the intervention developers, as they aptly identified and understood the most salient socio-cultural needs and preferences of members of this subcultural group and thus introduced a supplemental case management component to address these needs and enhance the original EBI.

Exemplar of a Culturally Grounded Substance Abuse Prevention Intervention

The Drug Resistance Strategies (DRS) Project was initiated in 1991 with the aim of developing a culturally focused prevention program tailored for effectiveness with minority youths (Botvin et al. 1994, 1995). The resulting “keepin' it REAL” drug prevention curriculum was developed in Phoenix, Arizona from 1995 to 2002 (Marsiglia & Hecht 2005). It involved white nonminority, Latino/a, and African American middle school and high school youths from large city high schools in creating and evaluating a culturally grounded substance abuse prevention curriculum. Youths participated in the development of prevention intervention videos that featured African American and Latino youths who modeled ways to refuse solicitations to use alcohol, tobacco, or drugs (Alberts et al. 1991; Hecht et al. 1992, 1993; Polansky et al. 1999; Schinke et al. 1991). These videos included white, Latino, and African American protagonists who promoted prosocial cultural values and norms. For example, for Latino youths, these videos endorsed familism, ethnic identification with Latino peers and family, traditional Latino cultural practices, and speaking the Spanish language.

The keepin' it REAL curriculum targeted theory-based social mediators (e.g., cultural norms that oppose substance use and economic deprivation) as core intervention components and also targeted several protective factors (e.g., strong role models, educational successes, school bonding, adaptation to stresses, and positive attitudes) (Clayton et al. 1995, Hawkins et al. 1992, Moon et al. 2000). The keepin' it REAL evaluation of youth involvement yielded positive results on their involvement in developing the substance abuse prevention videos (Holleran et al. 2002).

The evaluation of the effectiveness of the keepin' it REAL intervention also showed that students from the experimental schools, relative to the comparison schools, acquired higher levels of drug resistance skills and adopted more conservative norms that eschew substance use; they also exhibited lower rates of alcohol use and less positive attitudes toward drug use (Kulis et al. 2005). The keepin' it REAL curriculum is now recognized as a model program by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and has been disseminated nationally and internationally.

In contrast to the positive results for Mexican American and other Latino youths in Arizona, when this intervention was exported to Texas, the local Mexican American youths responded critically to the videos, expressing that they “could not relate” to certain content and activities that were depicted, such as break dancing, even though these videos incorporated Mexican American youths as protagonists (Holleran et al. 2005). This revelation prompted the need for a local adaptation of the keepin' it REAL intervention in accord with the needs and preferences of youths who live in Texas communities (Holleran Steiker 2008).

As another example, based on of the need for a developmental adaptation, the keepin' it REAL curriculum was adapted for a fifth-grade subcultural group. Using focus groups, the adaptation team consulted with teachers who commented on the language, scenarios, and activities prior to the pilot studies. The curriculum development specialists then adapted the existing curriculum over a six-month period to make the lessons developmentally appropriate for fifth-graders and added two lessons to enhance intervention effects. The fifth-grade version utilized the same basic curriculum content as the standard seventh-grade multicultural version. The adapted activities involved adjustments in communication level/format and greater concreteness in the presentation of concepts. Other adaptations addressed age-based relevance in the examples, including simplification in language and concepts and more age-relevant ways to model and practice resistance skills using realistic situations.

Issues, Answers, and Abiding Challenges

Regarding our current state of knowledge about the cultural adaptation of EBIs, we summarize and comment on answers to four major issues as framed according to the four key questions.

Are cultural adaptations developed from original EBIs justifiable? Generally, the cultural adaptation of EBIs appears justifiable when the original EBI exhibits one of four types of diminished intervention effects. Cultural adaptations are justified under the conditions of (a) ineffective client engagement, (b) unique risk or resilience factors in a subcultural group, (c) unique symptoms of a common disorder that the original EBI was not designed to influence, and (d) poor intervention effectiveness with a particular subcultural group.

What procedures should intervention developers follow when conducting a cultural adaptation? To guide the design and implementation of a culturally adapted EBI, we now have a variety of stage models, most of which exhibit similar stages for conducting a cultural adaptation of an EBI. Thus, the basic pathways for planning and conducting cultural adaptations have now been charted and involve variations of four stages: (a) information gathering, (b) developing preliminary adaptation designs, (c) conducting preliminary tests of adaptation, and (d) adaptation refinement (Barrera & Castro 2006).

What is the evidence that cultural adaptations are effective? The evidence for the effectiveness of cultural adaptations is promising but mixed. It appears that culturally adapted interventions are approximately as effective as the original EBI. Ideally, the adapted intervention would provide a significant increment of improvement on targeted outcome measures, although few studies have conducted direct comparisons of this effect. Accordingly, we do not have sufficient evidence to address this issue with certainty, and this calls for future studies that are designed to test this effect. This issue raises another challenge involving the costs and benefits of developing a culturally adapted intervention. Is it worth the cost and effort of designing and evaluating such adaptations, if the effect sizes (and thus effectiveness) on targeted outcomes are approximately equal to those attained under the original EBI? Such adaptations might provide demonstrable gains in consumer participation and satisfaction, but are these gains sufficient to merit the effort and expense involved in designing a cultural adaptation of an EBI?

How can within-group cultural variation be accommodated in a cultural adaptation? Regarding responsiveness to within-group variation, two classes of answers are evident. This problem of within-group variation can be addressed by (a) population segmentation, which involves more narrowly defining a targeted subcultural group (attenuating within-group variability), and (b) adaptive interventions of various types.

Directions for Future Development

Direct comparisons between original EBIs and adapted versions

In comparative outcome trials, culturally adapted interventions have usually been contrasted with a control condition and not with unaltered versions of the original EBI (Griner & Smith 2006). In principle, the essential justification for a cultural adaptation is its superiority to the original EBI in terms of participant engagement, targeted outcomes, or both. Comparative research of this type is needed. Now that informative frameworks exist to guide the design of cultural adaptations of EBIs, it will be particularly interesting to compare an original EBI to a rigorously adapted EBI to evaluate possible enhancements in the effectiveness of the adapted EBIs.

An ecodevelopmental approach to cultural adaptation

Given the emerging emphasis of systemic approaches in the conceptualization and application of culture (Castro et al. 2009, Erez & Efrat 2004, Szapocznik & Coatsworth 1999), the use of systemic models for adaptation planning and implementation is clearly indicated. A proposed cultural adaptation should consider the influences of various cultural elements such as religion, gender, and social class (Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2006, Cohen 2009). In addition, this adaptation should also consider the influences of surrounding community and socioeconomic factors that can enhance or diminish the effect of the EBI on targeted therapeutic outcomes. A systemic analysis of antecedent factors, mediators, and outcomes and of ways to boost intervention effects would be useful in efforts to maximize the overall benefits of such adapted EBIs.

Understanding underlying mechanisms of cultural adaptations

To generate new and generalizable scientific knowledge, it is beneficial to understand an intervention's mechanisms of change, as this understanding can identify critical intervention components that influence behavioral and other mediators that in turn influence the intended therapeutic outcomes (Kazdin 2008, MacKinnon et al. 2002). In addition, a study of cultural moderator variables, e.g., level of acculturation among subcultural groups of Latino clients (low acculturated, bicultural, and high acculturated) could reveal that the influence of a cultural element (e.g., the role of respeto—a respectful demeanor utilized by the therapist or interventionist) produces strong and significant intervention effects for Latino subgroup A1 (e.g., low-acculturated Latinos), yet produces no effect for Latino subgroup A2 (e.g., high-acculturated Latinos).

In this regard, intervention outcome research can be used not only to evaluate the efficacy of an intervention, but also to test theory (Howe et al. 2002). When cultural adaptations are explicitly designed to influence a cultural construct hypothesized as important for therapeutic change (to lower acculturative stress, increase trust in the therapist, or strengthen cultural identity), such studies may test if the intervention was successful in changing that construct (action theory) and also if that change affected the outcome (conceptual theory) (see MacKinnon et al. 2002).

Developing adaptive culturally adapted interventions

As noted above, adaptive interventions offer different dosages of intervention components to various types of clients, depending on the needs of individual clients, under explicit decision rules for determining variations in dosages. The specification of an array of client-dosage decision rules would establish an intervention protocol that could be tested and replicated in clinical practice and in research settings. Such adaptive approaches hold considerable promise for prescriptive cultural adaptations that can be applied with multiple subcultural groups. Moreover, a series of studies on the effects of selected cultural moderator variables (e.g., acculturation, immigration experience, religiosity) could further inform the decision rules developed for these prescriptive adaptive interventions.

Some Recommendations

Utilize available frameworks and stage models to guide the cultural adaptation process

Remarkable similarity exists in the frameworks and stage models that have been developed to systematically guide the cultural adaptation of EBIs, even though these appear to have been developed independently (Barrera & Castro 2006, D'Angelo et al. 2009, Domenech Rodríguez & Wieling 2004, Kumpfer et al. 2008, McKleroy et al. 2006, Wingood & DiClemente 2008). Collectively, these frameworks and models advocate the use of existing research that identifies the presence of unique risk and resilience factors that should be considered in intervention revisions. These approaches all contain early steps that employ focus groups, marketing research strategies, and the formation of community partnerships that allow potential consumers to inform the proposed intervention. All employ the integration of qualitative and quantitative research methods. After a step that involves preliminary revisions, all approaches include pilot research and another opportunity to learn directly from people who resemble the intended consumers of the proposed cultural adaptation. Ultimately, these stages lead to a refined intervention that can be implemented with fidelity in broader-scale outcome research. Based on preliminary findings, these frameworks can be used to refine and implement effective cultural adaptations.

Specify core components and mechanisms of effect

The developers of an original EBI, and those who propose an adaptation to that EBI, should present and describe a theory-based model that specifies their intervention's putative core components and its related mechanisms of effect on targeted outcome variables. This theory-based analysis of expected core component effects and mechanisms, as illustrated by Barrera & Castro (2006), would inform users of the intervention and would help research scientists to understand the role of the intended components and their intended therapeutic effects. This would involve a formal core components analysis that utilizes the mediational analysis model presented by MacKinnon et al. (2002) and/or that utilizes a logic model approach, as has been conducted within health services and evaluation research studies (Goldman & Schmalz 2006, Gugiu & Rodriguez-Campos 2007).

Importance of cultural competence of therapists and intervention agents

Finally, frameworks for guiding the process of culturally adapting interventions often focus on intervention content rather than on the personnel who deliver the interventions. Whether in a treatment setting or in a community setting, the analyses by Bernal et al. (1995) and Hwang (2006) remind us that cultural competence and other clinical skills of the intervention agents are essential for delivering effective culturally adapted EBIs. Thus, one essential aspect of a cultural adaptation should be the specification of personnel skills and training for the cultural competence necessary to effectively implement the culturally adapted EBI.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by grants from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities: Grant Number P20MD002316-010003, Felipe González Castro, Principal Investigator, and Grant Number P20MD002316-01, Flavio F. Marsiglia, Principal Investigator. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Center on Minority Health and Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.