Abstract

Study Objectives:

Determine effects of low-dose estradiol and low-dose venlafaxine on self-reported sleep measures in menopausal women with hot flashes.

Design:

3-arm double-blind randomized trial. Participants assigned in a 2:2:3 ratio to 17β estradiol 0.5 mg/day (n = 97), venlafaxine XR 75 mg/day (n = 96), or placebo (n = 146) for 8 weeks.

Setting:

Academic research centers.

Participants:

339 community-dwelling perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with ≥ 2 bothersome hot flashes per day.

Measurements and Results:

Insomnia symptoms (Insomnia Severity Index [ISI]) and sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]) at baseline, week 4 and 8; 325 women (96%) provided ISI data and 312 women (92%) provided PSQI data at baseline and follow-up. At baseline, mean (SD) hot flash frequency was 8.1/day (5.3), mean ISI was 11.1 (6.0), and mean PSQI was 7.5 (3.4). Mean (95% CI) change from baseline in ISI at week 8 was −4.1 points (−5.3 to −3.0) with estradiol, −5.0 points (−6.1 to −3.9) with venlafaxine, and −3.0 points (−3.8 to −2.3) with placebo (P overall treatment effect vs. placebo 0.09 for estradiol and 0.007 for venlafaxine). Mean (95% CI) change from baseline in PSQI at week 8 was −2.2 points (−2.8 to −1.6) with estradiol, −2.3 points (−2.9 to −1.6) with venlafaxine, and −1.2 points (−1.7 to −0.8) with placebo (P overall treatment effect vs. placebo 0.04 for estradiol and 0.06 for venlafaxine).

Conclusions:

Among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes, both low dose oral estradiol and low-dose venlafaxine compared with placebo modestly reduced insomnia symptoms and improved subjective sleep quality.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Citation:

Ensrud KE, Guthrie KA, Hohensee C, Caan B, Carpenter JS, Freeman EW, LaCroix AZ, Landis CA, Manson J, Newton KM, Otte J, Reed SD, Shifren JL, Sternfeld B, Woods NF, Joffe H. Effects of estradiol and venlafaxine on insomnia symptoms and sleep quality in women with hot flashes. SLEEP 2015;38(1):97–108.

Keywords: randomized trial, estradiol, venlafaxine, sleep, hot flashes, menopause

INTRODUCTION

Vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) and sleep disturbance are common in perimenopausal and post-menopausal women and have been identified as key symptoms of the menopausal transition.1–4 Previous population-based studies of women in the menopausal transition have found that those with vasomotor symptoms are more likely to report sleep disturbances and to meet diagnostic criteria for chronic insomnia.5,6

Estrogen therapy with or without progestin (hormone therapy) remains the predominant treatment for vasomotor symptoms, but current guidelines recommend its use at the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration because of the complex pattern of risks and benefits demonstrated with use of combined hormone therapy in postmenopausal women.7–9 Increasingly prescribed to women in midlife, selective serotonin and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs) have shown modest efficacy in reducing hot flash frequency and severity in previous randomized trials,10,11 and a low dose of the SSRI paroxetine12 was recently approved by the FDA as the first non-hormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms.13 In particular, the SNRI venlafaxine is effective in reducing hot flashes in healthy postmenopausal women14 and breast cancer survivors,15 is available in an generic extended release form, and has few drug-drug interactions, making it a viable option in the primary care practice setting.

Few randomized trials of hormonal and non-hormonal pharmacologic treatments for vasomotor symptoms have systematically evaluated the effect of the intervention on self-reported sleep disturbance. There is some evidence to suggest that treatment with hormone therapy reduces sleep disturbance among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women,8 including women with vasomotor symptoms,16 but the effect is small in magnitude. On the other hand, use of SSRIs/SNRIs for treatment of hot flashes has been limited by concerns about commonly reported side effects in patients treated with SSRIs/SNRIs for anxiety and depression, including insomnia and somnolence.4,17 Previous placebo-controlled randomized trials of SNRIs for treatment of hot flashes in healthy postmenopausal women14,18,19 have not systematically collected sleep outcome data, but a recent randomized trial20 in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms demonstrated that the SSRI escitalopram compared with placebo reduced insomnia symptoms and improved subjective sleep quality.

Importantly, no previous placebo-controlled randomized trial has simultaneously evaluated the relative effects of hormone therapy and SSRI/SNRI medications on sleep complaints in menopausal women with hot flashes. We systematically collected validated, self-reported measures of sleep in a 3-arm randomized double-blind trial designed primarily to evaluate the effects of both low-dose 17β estradiol and low-dose venlafaxine as compared with placebo on the frequency of menopausal hot flashes. As previously reported,21 the reduction in daily hot flash frequency (compared with placebo) was 2.3 with estradiol and 1.8 with venlafaxine. We hypothesized that low-dose estradiol and low-dose venlafaxine would each be superior to placebo in reducing insomnia symptoms and improving subjective sleep quality and now report the effects of each treatment as compared with placebo on these a priori specified secondary sleep outcomes and examine whether any observed effects varied across risk subgroups defined by participant characteristics measured at baseline.

METHODS

Overview

The study was a 3-arm double-blind randomized trial of low-dose estradiol, low-dose venlafaxine and placebo conducted at 3 Menopause Strategies Finding Lasting Answers for Symptoms and Health (MsFLASH) network sites (see Acknowledgments). Details about the MsFLASH Research Network, study design, methods, and main trial results have been reported elsewhere.21,22 The primary objective of the trial was to determine the efficacy of both estradiol and venlafaxine relative to placebo in reducing self-reported mean daily (7-day average) hot flash frequency at 4 and 8 weeks. Self-reported sleep measures (insomnia symptoms as assessed by the Insomnia Severity Index [ISI] and subjective sleep quality as assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]) at 4 and 8 weeks were a priori specified secondary outcomes. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Between November 2011 and October 2012, the study enrolled 339 women. Eligible women were: aged 40–62 years and in general good health; in the menopause transition (amenorrhea ≥ 60 days in the past year), postmenopausal (≥ 12 months since last menstrual period or bilateral oophorectomy), or had undergone hysterectomy with 1 or more ovaries remaining and had follicle stimulating hormone level > 20 mIU/mL and estradiol level ≤ 50 pg/mL; and reported ≥ 14 hot flashes/night sweats per week (recorded on daily diaries for 3 weeks), at least some of which were rated as bothersome or severe (i.e. rated as bothersome or severe on at least four 12-h [day/night] blocks of times in each week of screening hot flash diary completion). Exclusion criteria, described in detail elsewhere21 included: use of psychotropic medications in the past month; use of prescription, nonprescription or herbal therapies for hot flashes in the past month; use of hormone therapy, hormonal contraceptives, selective estrogen receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors in the past 2 months; current severe illness; current major depressive episode; drug or alcohol abuse in the past year; suicide attempt in the past 3 years; and lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or psychosis. Women with uncontrolled hypertension; history of myocardial infarction, angina, or cerebrovascular events; or history of endometrial, ovarian or breast cancer or breast pre-cancer condition were also excluded from participation.

Treatment and Study Procedures

After a telephone screen, women potentially eligible and interested in participation were mailed a baseline questionnaire and daily diaries for recording frequency, severity, and bother of hot flashes each morning and evening. Women who continued to meet eligibility criteria were scheduled for 2 clinic visits (screening and randomization) within a 2–3 week interval. At the randomization visit, eligible women were randomized using a dynamic algorithm21 in a 2:2:3 ratio to treatment groups of identical-appearing (one pill orally per day) 17β-estradiol 0.5 mg/day, venlafaxine XR 37.5 mg/day, or placebo, balanced on clinical site. Randomization to treatment assignment in the 2:2:3 ratio (estradiol: venlafaxine: placebo) was utilized to maximize efficiency of the trial design for the comparisons between each active treatment and placebo groups. Participants, investigators, and clinical center staff were blinded to treatment assignment. After one week, the dose of venlafaxine was increased in a blinded manner from 37.5 to 75 mg/day. A telephone contact was made at weeks 1 and 4 after randomization; a final clinic visit was conducted at week 8.

Assessment of Insomnia Symptoms

Participants completed the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)23–25 at baseline and week 4 and 8 of treatment, a valid and reliable self-administered instrument that measures perception of current (past 2 weeks) insomnia symptoms. The index consists of 7 items assessing difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, problems with early awakening, satisfaction with current sleep pattern, interference of sleep problem with daily functioning, noticeability of impairment attributed to the sleep problem, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problem. Each item is rated on a 0–4 point scale (total score 0–28), with higher scores suggesting more severe insomnia symptoms. The absence of insomnia is indicated by scores 0–7, sub-threshold or mild insomnia by scores 8–14, clinical insomnia of moderate severity by scores 15–21, and severe clinical insomnia by scores 22–28. In addition, a cutoff score of 10 has been reported to be optimal (86.1% sensitivity and 87.7% specificity) in detecting insomnia cases in a community sample of 959 adults aged 18 years and older.26 Trials of pharmacologic and behavioral interventions in patients with insomnia have suggested that the ISI is sensitive in measuring treatment response.27,28

Assessment of Subjective Sleep Quality

Participants also completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) at baseline and 4 and 8 weeks of treatment. The PSQI, a validated measure of subjective sleep quality and sleep disturbances over a one-month time period, assesses subjective sleep quality, sleep-onset latency, duration, and efficiency; sleep disturbances; use of sleeping medication; and daytime dysfunction.29,30 Global PSQI scores range from 0–21 with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. Cutoffs of 5 and 8 have been reported to indicate poor sleep quality, depending on the population.29,31 The PSQI has been shown to be sensitive in measuring response to cognitive behavioral therapy in randomized trials conducted in patients with insomnia.32

Other Measurements

Frequency of hot flashes/night sweats was recorded on daily diaries in the morning and evening throughout the study and reported as the total number of daytime hot flashes and night sweats in a 24-h period. The baseline measure reported in the paper was calculated as the mean of daily reported hot flashes/night sweats in the first 2 weeks of the screening period. Demographic factors, smoking status, alcohol intake, menopausal status (menopause transition, postmenopause), and health status were assessed by questionnaire at baseline. Validated questionnaires at baseline also evaluated depressive symptoms (9-item scale from the Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]),33 anxiety (7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale [GAD-7]),34 and pain intensity and interference (3-item PEG scale).35 Height and body weight were measured at baseline and used to calculate a standard body mass index (BMI).

Adverse events were assessed at each contact by asking open-ended questions. In addition, women were asked to complete a self-administered symptom questionnaire listing 27 specific reported side effects for estrogen therapy or venlafaxine including fatigue/tiredness, drowsiness, or difficulty sleeping/ insomnia. Participants reported whether they had experienced any of these reported side effects during the past 4 weeks at baseline and at the week 4 and 8 follow-up visits.

Statistical Analysis

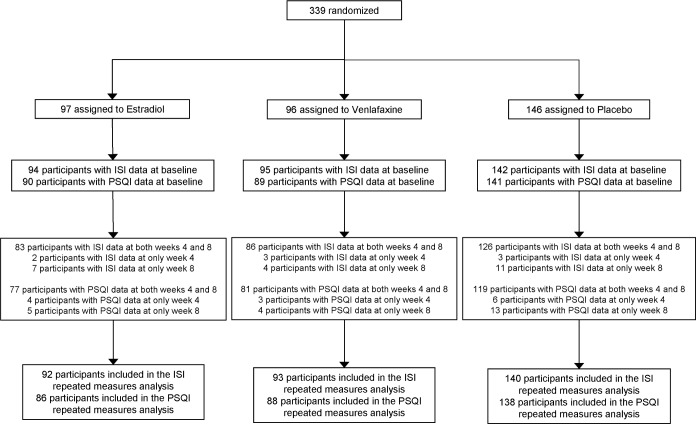

All analyses included all randomized participants with follow-up sleep measurements, which were collected irrespective of adherence to study medication. Of the cohort of 339 randomized participants, 325 women (96%) completed the ISI and 312 (92%) completed the PSQI at follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram for data collection of sleep outcome measures.

Primary analyses consisted of treatment group contrasts between each active treatment group and placebo computed as Wald statistics from repeated measures linear regression models summarizing ISI and PSQI at both 4 and 8 weeks as a function of treatment assignment, clinical center, week number (visit), and baseline value of the sleep outcome measure. The primary hypotheses for this analysis were that low-dose estradiol and low-dose venlafaxine would each be superior to placebo in reducing insomnia symptoms and improving subjective sleep quality. Robust standard errors were calculated using generalized estimating equations to account for correlation between repeated measures from each participant. We hypothesized that the effect of each treatment on sleep outcome measures might be modified by the following characteristics measured at baseline: race/ethnicity, menopausal status, nocturnal hot flash frequency, depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), pain intensity and interference (PEG), body mass index (BMI), and insomnia symptoms (ISI). Tests of interaction between treatment assignment and each of these variables were performed within the linear regression models (using continuous values of variables where possible) for each active treatment versus placebo comparison. Nominal P-values are presented for the 32 potential interactions examined. Thus, on average, one to two P-values would be expected to be statistically significant by chance alone at the 0.05 level.

Secondary analyses examined the proportion of women in each treatment group with clinical improvement in sleep measures, defined as ≥ 50% decrease from baseline to 8 weeks in the ISI (PSQI); comparisons between each active treatment group and placebo group were performed using unadjusted χ2 tests.

The planned sample size of the trial (304 women) was determined by the primary trial endpoint (hot flash frequency).21 Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with 2-sided P-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

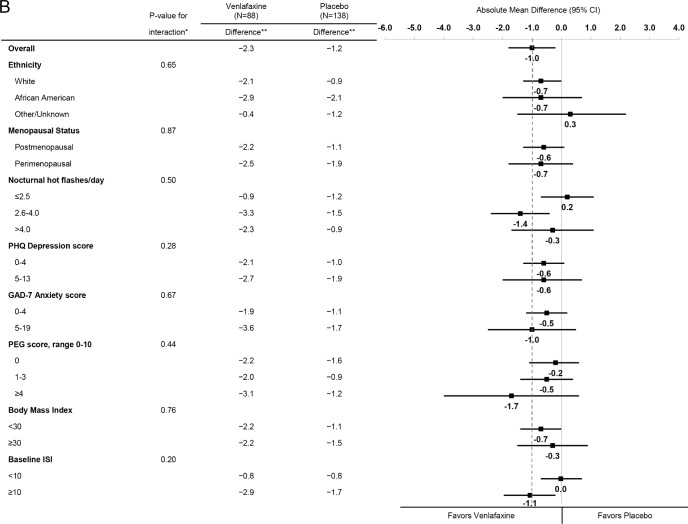

A total of 339 women were randomly assigned to receive low-dose estradiol (n = 97); low-dose venlafaxine (n = 96), or placebo (N = 146) (Figure 1). The mean (SD) age of the participants was 54.6 (3.8) years and mean (SD) daily hot flash frequency was 8.1 (5.3). The correlation between ISI and PSQI at baseline was 0.73. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the treatment groups (Table 1). During the 8-week treatment period, 94% of the women in each group were adherent to their study medication as defined by taking ≥ 80% of dispensed pills.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by treatment assignment.

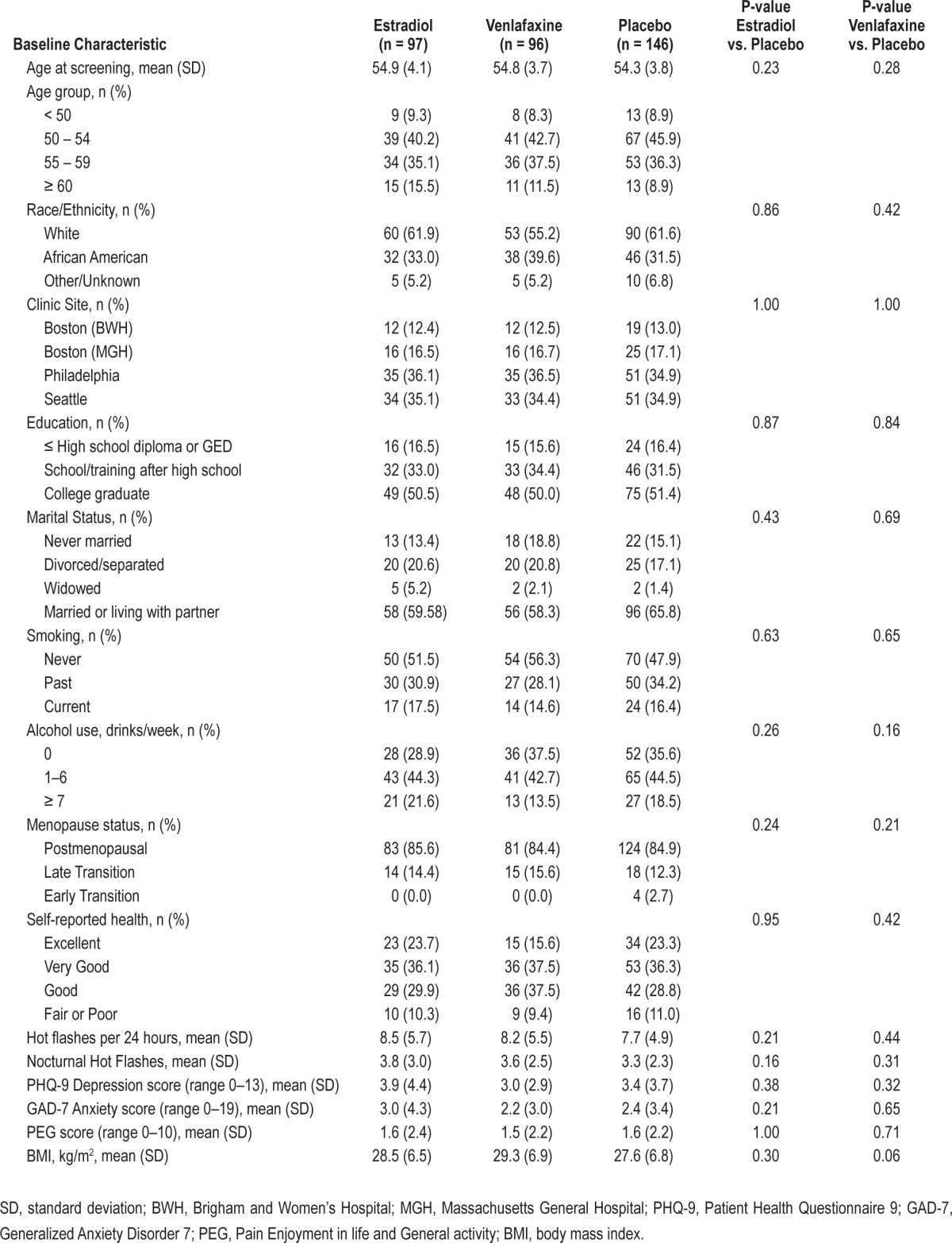

Insomnia Symptoms

A total of 325 women (96% of randomized participants) completed baseline and at least one follow-up measure of ISI. At baseline, mean (SD) ISI was 11.0 (6.0); 131 women (40.3%) were classified with mild (sub-threshold) insomnia (ISI 8–14), 76 (23.4%) with moderate clinical insomnia (ISI 15–21), and 14 (4.3%) with severe clinical insomnia (ISI 22–28). One hundred ninety-one women (58.8%) had a baseline ISI ≥ 10. Treatment with estradiol and treatment with venlafaxine reduced the ISI compared with placebo (P overall treatment effect 0.09 estradiol vs. placebo, and 0.007 venlafaxine vs. placebo) in models adjusted for site, visit, and baseline ISI (Table 2), though treatment effects were modest in magnitude and in the case of estradiol, not at the 0.05 level of significance. Compared to baseline, the mean (95% CI) change in ISI at week 8 was −4.1 points (−5.3 to −3.0) in the estradiol group (38% reduction), −5.0 points (−6.1 to −3.9) in the venlafaxine group (43% reduction), and −3.0 (−3.8 to −2.3) in the placebo group (29% reduction). Findings were similar at week 4. There was a 0.9 point greater decrease in ISI at 8 weeks in the venlafaxine group compared to the estradiol group, with a 95% CI around this difference of −2.4 to 0.7 points. Clinical improvement at week 8 (≥ 50% decrease from baseline in ISI) was observed in 47% of women in the estradiol group, 49% of women in the venlafaxine group, and 35% of women in the placebo group (P active treatment vs. placebo 0.07 for estradiol and 0.04 for venlafaxine).

Table 2.

Mean ISI and PSQI by treatment assignment.

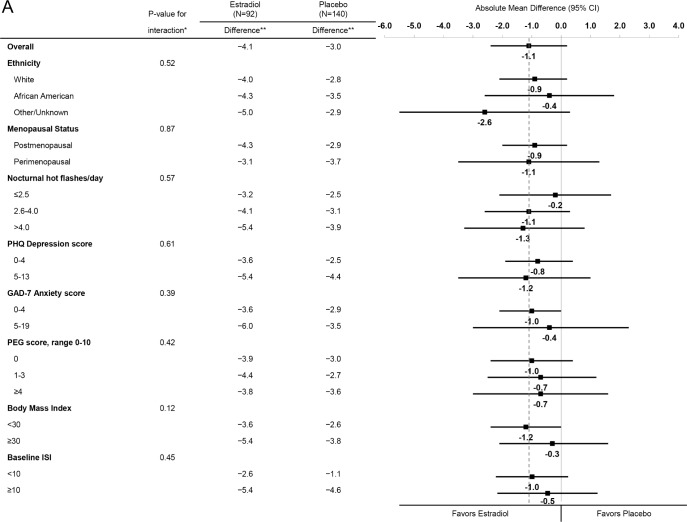

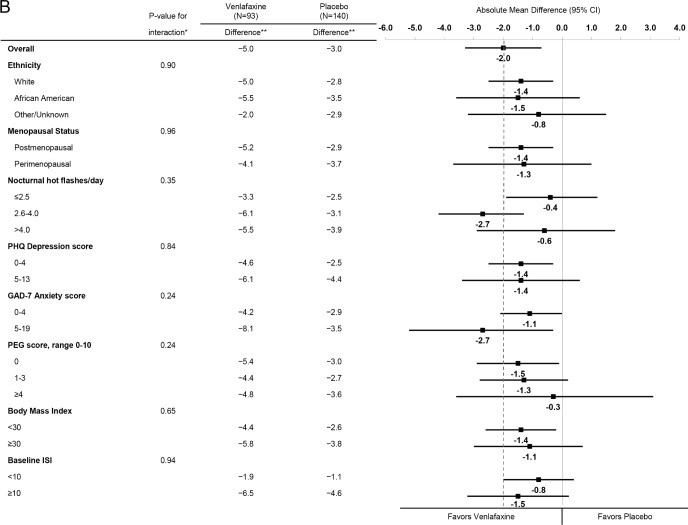

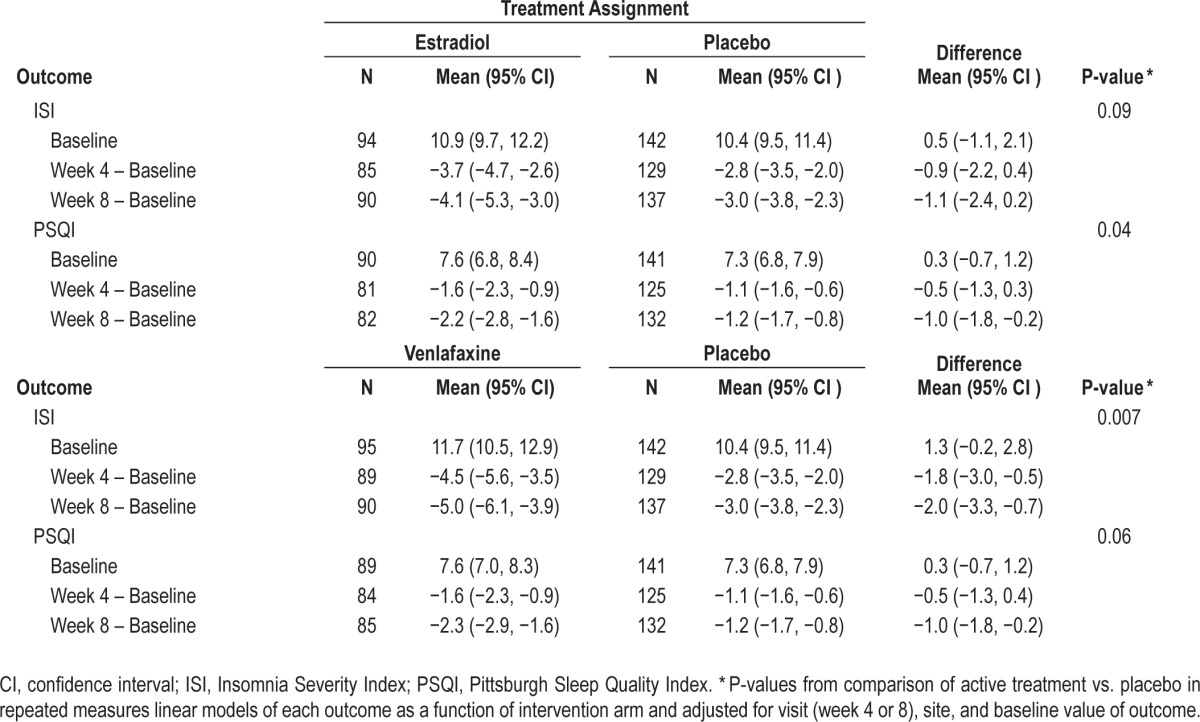

Across strata of baseline participant characteristics including baseline insomnia symptoms, similar reductions in the ISI were observed for estradiol (Figure 2A) and for venlafaxine (Figure 2B). There was no evidence of an interaction between treatment assignment and race/ethnicity, menopausal status, nocturnal hot flash frequency, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, pain intensity and interference, BMI, or insomnia symptoms (P values for interaction terms between treatment assignment and subgroup ≥ 0.12 for estradiol and ≥ 0.24 for venlafaxine).

Figure 2A.

Mean change in ISI from Baseline to Week 8 by treatment assignment overall and within risk subgroups. The dotted vertical line indicates the overall absolute mean difference between treatment groups. * Adjusted absolute mean differences and interaction P-values are computed from a repeated measures model estimating mean week 4 and 8 ISI as a function of treatment arm, site, baseline ISI, the subgroup of interest, and the interaction between treatment assignment and subgroup. ** Mean week 8 ISI – baseline ISI difference.

Figure 2B.

Mean change in ISI from Baseline to Week 8 by treatment assignment overall and within risk subgroups. The dotted vertical line indicates the overall absolute mean difference between treatment groups. * Adjusted absolute mean differences and interaction P-values are computed from a repeated measures model estimating mean week 4 and 8 ISI as a function of treatment arm, site, baseline ISI, the subgroup of interest, and the interaction between treatment assignment and subgroup. ** Mean week 8 ISI – baseline ISI difference.

Subjective Sleep Quality

A total of 312 women (92% of randomized participants) completed baseline and at least one follow-up measure of PSQI. At baseline, mean (SD) PSQI was 7.5 (3.5); 115 women (36.9%) were classified as having very poor subjective sleep quality (PSQI > 8) and 220 (70.5%) were classified as having poor subjective sleep quality (PSQI > 5). Treatment with estradiol and treatment with venlafaxine resulted in similar small reductions in PSQI compared with placebo (P overall treatment effect 0.04 estradiol vs. placebo and 0.06 venlafaxine vs. placebo) in models adjusted for site, visit, and baseline PSQI, though the comparison between venlafaxine and placebo did not quite reach the level of significance (Table 2). Compared to baseline, the mean (95% CI) change in PSQI at week 8 was −2.2 points (−2.8 to −1.6) in the estradiol group (29% reduction), −2.3 points (−2.9 to −1.6) in the venlafaxine group (30% reduction), and −1.2 points (−1.7 to −0.8) in the placebo group (16% reduction). The effect of both treatments on PSQI was most evident at week 8. There was a 0.1 point greater decrease in PSQI at week 8 in the venlafaxine group compared to the estradiol group with a 95% CI around this difference of −0.9 to 1.0 points. Clinical improvement at week 8 (≥ 50% decrease from baseline in PSQI) was observed in 38% of women in the estradiol group, 25% of women in the venlafaxine group, and 18% of women in the placebo group (P active treatment vs. placebo 0.001 for estradiol and 0.20 for venlafaxine).

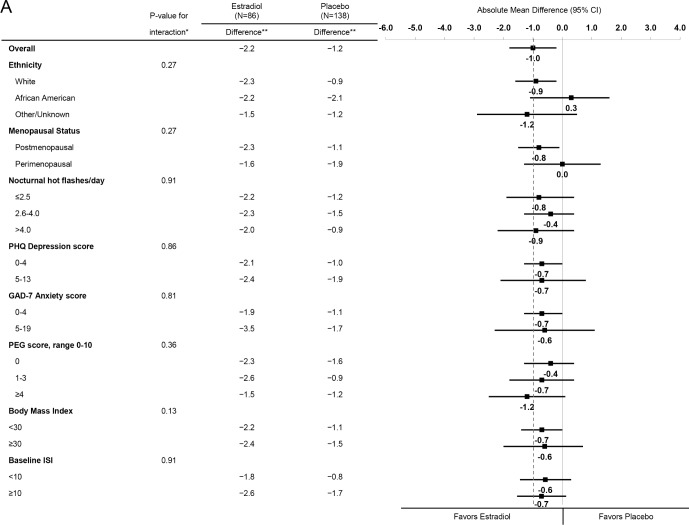

Effects of estradiol (Figure 3A) and venlafaxine (Figure 3B) in reducing PSQI were similar across strata of baseline participant characteristics. There was no evidence of an interaction between treatment assignment and race/ethnicity, menopausal status, nocturnal hot flash frequency, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, pain intensity and interference, BMI, or insomnia symptoms (P values for interaction terms between treatment assignment and subgroup ≥ 0.13 for estradiol and ≥ 0.20 for venlafaxine).

Figure 3A.

Mean change in PSQI from Baseline to Week 8 by treatment assignment overall and within risk subgroups. The dotted vertical line indicates the overall absolute mean difference between treatment groups. * Adjusted absolute mean differences and interaction P-values are computed from a repeated measures model estimating mean week 4 and 8 PSQI as a function of treatment arm, site, baseline PSQI, the subgroup of interest, and the interaction between treatment assignment and subgroup. ** Mean week 8 PSQI – baseline PSQI difference.

Figure 3B.

Mean change in PSQI from Baseline to Week 8 by treatment assignment overall and within risk subgroups. The dotted vertical line indicates the overall absolute mean difference between treatment groups. * Adjusted absolute mean differences and interaction P-values are computed from a repeated measures model estimating mean week 4 and 8 PSQI as a function of treatment arm, site, baseline PSQI, the subgroup of interest, and the interaction between treatment assignment and subgroup. ** Mean week 8 PSQI – baseline PSQI difference.

Sleep Adverse Events

Newly emergent adverse events (AEs) were reported by 56% of women in the estradiol group, 69% of the women in the venlafaxine group, and 62% of women in the placebo group (P active treatment vs. placebo 0.39 for estradiol and 0.26 for venlafaxine). There were no statistically significant differences between the estradiol and placebo groups in newly emergent complaints of fatigue/tiredness (13% vs. 22%, P = 0.18) or drowsiness (4% versus 9%, P = 0.21), but there was some evidence that women in the estradiol group were more likely to report new onset difficulty sleeping/insomnia (33% vs. 14%, P = 0.03). There were no statistically significant differences between the venlafaxine and placebo groups in newly emergent complaints of fatigue/tiredness (33% vs. 22%, P = 0.13), drowsiness (16% vs. 9%, P = 0.12), or difficulty sleeping/insomnia (27% vs. 14%, P = 0.12).

DISCUSSION

In perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes, treatment with low-dose venlafaxine and treatment with low-dose estradiol were each modestly more effective than placebo in reducing insomnia symptoms and improving subjective sleep quality. These results provide clinically relevant information for health care providers and women by demonstrating that these two commonly prescribed hormonal and non-hormonal medications for treatment of vasomotor symptoms have similar small benefits on frequently co-occurring sleep complaints.

It is noteworthy that insomnia and poor subjective sleep quality were common in this cohort of midlife women with hot flashes who, on average, reported minimal symptoms of depression, anxiety or pain. Over one-fourth of women at baseline had an ISI > 14, suggestive of a clinical diagnosis of at least moderate insomnia, and 59% had an ISI ≥ 10, a cutoff that has been reported to be optimal in detecting insomnia cases in a community sample of adults aged ≥ 18 years.26 In addition, nearly 37% had very poor subjective sleep quality as defined using a threshold of 8 on the PSQI, and 71% had poor subjective sleep quality as defined by a PSQI > 5. These results are in agreement with those reported in similar randomized trial study populations20,36 and population-based studies in midlife women not selected on the basis of hot flashes1,6,37 that have identified an independent association of the presence of hot flashes or higher hot flash frequency with self-reported sleep complaints.

We found that treatment with low-dose estradiol compared with placebo reduced the ISI by 1.1 points and that 47% the women in the estradiol group versus 35% in the placebo group reported that insomnia symptoms decreased by at least 50% from baseline, albeit these differences between estradiol and placebo groups did not quite reach the level of significance. In addition, women treated with estradiol compared with those treated with placebo had a 1.0 point greater reduction in the PSQI, and clinical improvement in subjective sleep quality (as defined by ≥ 50% reduction in PSQI from baseline) was more common in the estradiol group (38%) as compared with the placebo group (18%); both of these comparisons between estradiol and placebo were statistically significant. Previous randomized trials of low dose estrogen in combination with progestin compared with placebo38 and calcium supplementation16 in post-menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms have reported similar modest improvements in difficulty sleeping as assessed by a single question on the Greene Climacteric Scale. In addition, some,39–41 but not all,42 placebo-controlled randomized trials of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women not selected on the basis of vasomotor symptoms have reported a small benefit of hormone therapy including unopposed low-dose estradiol on self-reported sleep measures.

While sleep disruption may emerge with initiation of SSRI/ SNRI treatment, we found that treatment with low-dose venlafaxine compared with placebo reduced the ISI by 2.0 points at week 8, demonstrating a modest effect of venlafaxine in decreasing insomnia symptoms. In addition, treatment with venlafaxine reduced the PSQI at 8 weeks by 1.1 points indicating a small improvement in subjective sleep quality, though the effect of venlafaxine on PSQI did not quite reach the level of significance. Nearly one-half of the women in the venlafaxine group versus 35% in the placebo group reported that insomnia symptoms decreased by at least 50% from baseline; clinical improvement in self-reported sleep quality was smaller than the reduction in insomnia symptoms (25% in estradiol group vs. 18% in placebo group), and the comparison was not significant. Most previous placebo-controlled randomized trials of SNRIs including venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine for treatment of hot flashes in healthy postmenopausal women14,18,19 and survivors of breast cancer15 have not systematically collected sleep outcome data, though one small trial of venlafaxine in 57 breast cancer survivors43 found a greater percent reduction in PSQI with venlafaxine compared with placebo that failed to reach significance (18% vs. 8%, P = 0.34). Trials of SSRIs for treatment of menopausal hot flashes that have systematically assessed self-reported sleep measures include: trials of citalopram37 and escitalopram20 reporting benefit; a dose-ranging trial of paroxetine44 reporting mixed results; and another dose-ranging trial of paroxetine45 reporting no effect. In particular, the trial of the SSRI escitalopram that used the ISI and PSQI to assess sleep reported that treatment with escitalopram compared with placebo reduced ISI by 2.0 points and PSQI by 1.3 points at 8 weeks—effects nearly identical to those demonstrated with venlafaxine in this study.

We found that the effects of estradiol and venlafaxine on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality were consistent across risk subgroups defined at baseline by participant characteristics, including those based on level of nocturnal hot flash frequency and insomnia symptoms. Similarly, we previously reported that the effect of these treatments on hot flash frequency was consistent across risk subgroups categorized by level of insomnia symptoms.21 These findings add to the controversy regarding the exact role that hot flashes play in sleep complaints of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women46,47 and suggest that further research is warranted to examine the complexities of any inter-relationship.

A systematic review of the evidence from efficacy studies evaluating SSRIs and SNRIs for the treatment of major depression and anxiety disorders48 noted that insomnia is a commonly reported adverse event, but whether this observation generalizes to a population of healthy women with hot flashes without psychiatric illness is unknown. There were no statistically significant differences between venlafaxine and placebo groups in the frequency of newly emergent adverse events of difficulty sleeping/insomnia, fatigue, or drowsiness in this study. While the newly emergent adverse event of difficulty sleeping/insomnia (but not fatigue or drowsiness) was significantly more common among women in the estradiol group as compared with the placebo group, insomnia has not been reported to be a side effect of estradiol treatment in women with vasomotor symptoms in other placebo-controlled randomized trials. Thus, chance alone may be a viable explanation for this apparent difference in insomnia (as captured solely by adverse event reporting) between these two groups due to the myriad of complaints and conditions assessed during the reporting process.

This trial has limitations as well as strengths. The study population was comprised of healthy women selected on the basis of bothersome hot flashes. Thus, results may not be applicable to other groups such as unselected midlife women or women selected on the basis of mental health conditions. The effects of low-dose venlafaxine treatment and low-dose estradiol treatment on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality beyond 8 weeks were not evaluated. We examined several potential effect modifiers of treatment response, but analyses were limited by suboptimal power and multiple comparisons were performed. Polysomnography was not performed and findings of a trial with objectively measured sleep outcomes might differ from findings of this study of self-reported sleep measures. The ISI was designed as a screening measure of insomnia and the PSQI was designed to assess multiple sleep disturbances, but both instruments are used to assess a patient's perception of sleep and both quantify subjective elements of insomnia. While the efficacy of estradiol and venlafaxine relative to placebo in reducing insomnia symptoms and improving sleep quality appeared to be similar in magnitude, our trial was not adequately powered to determine with confidence that one treatment was non-inferior to another, as establishing non-inferiority requires a much larger sample size. We evaluated the effects of low-dose estradiol and low-dose venlafaxine; the effects of higher doses of these medications on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in menopausal women with hot flashes are uncertain. Our population was not selected on the basis of a diagnosis of insomnia and the reductions in ISI and PSQI we observed with estradiol and venlafaxine treatments were smaller than those recommended to represent meaningful improvements in trials of interventions for treatment of patients with clinical insomnia.26,32,49 Strengths of this trial include the racially diverse cohort of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women; inclusion of estradiol, venlafaxine, and placebo groups; use of valid and reliable instruments to measure insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality; high adherence to treatment; and nearly complete collection of sleep outcome measures.

Treatment with low-dose venlafaxine and treatment with low-dose estradiol in healthy menopausal women with hot flashes were each modestly more effective than placebo in reducing insomnia symptoms and improving subjective sleep quality. These results demonstrate that these two widely prescribed hormonal and non-hormonal medications for treatment of vasomotor symptoms have a similar small benefit on commonly coexisting sleep complaints. This information should be useful to providers in counseling women with vasomotor symptoms who are considering initiation of pharmacologic therapies. Future trials should evaluate the comparative efficacy of pharmacologic and behavioral treatments in improving insomnia symptoms in midlife women selected on the basis of sleep disturbance.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The study was supported by a cooperative agreement issued by the National Institute of Aging (NIA), in collaboration with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), and the Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH): #U01 AG032656, U01AG032659, U01AG032669, U01AG032682, U01AG032699, U01AG032700. Dr. Ensrud serves as a consultant on a Data Monitoring Committee for Merck Sharpe & Dohme. Dr. Otte reports consultant activities and honoraria from On Q Health, Inc. Dr. Shifren reports consultant activities for New England Research Institutes. Dr. Joffe reports research support from Cephalon/Teva; and consultant activities for Noven and Sunovion. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The MsFLASH research network was established under an NIH cooperative agreement to conduct studies of the efficacy of treatments for the management of menopausal hot flashes. The studies are sponsored by the National Institute of Aging (NIA), in collaboration with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), and the Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH).

The network sites that participated in this study were Boston, MA (Massachusetts General Hospital; Principal Investigators: Lee Cohen, MD, and Hadine Joffe, MD, MSc); Indianapolis, IN (Indiana University; Principal Investigator: Janet S. Carpenter, PhD, RN, FAAN); Oakland, CA (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; Principal Investigators: Barbara Stern-feld, PhD, and Bette Caan, PhD; and Philadelphia, PA (University of Pennsylvania; Principal Investigator: Ellen W. Freeman, PhD). The Data Coordinating Center of the network is based at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Principal Investigators: Andrea LaCroix, PhD and Katherine A. Guthrie, PhD. The chairperson is Kristine E. Ensrud, MD, University of Minnesota.

Other investigators of the MsFLASH Network that contributed to this study include Garnet Anderson, PhD, Joseph Larson, MS: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Institute, Seattle WA; Katherine Newton, PhD: Group Health Research Institute, Seattle WA; Susan D. Reed, MD, Nancy F. Woods, PhD, RN, Carol A. Landis, DNSc, RN: University of Washington, Seattle, WA, and Sheryl Sherman, PhD: National Institute on Aging/US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Author contributions: K.A. Guthrie had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors made substantial contributions to the study and this manuscript. None were compensated for the manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, et al. Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:230–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270153.59102.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tom SE, Kuh D, Guralnik JM, Mishra GD. Self-reported sleep difficulty during the menopausal transition: results from a prospective cohort study. Menopause. 2010;17:1128–35. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181dd55b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State-ofthe-Science Conference statement: management of menopause-related symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:1003–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kravitz HM, Zhao X, Bromberger JT, et al. Sleep disturbance during the menopausal transition in a multi-ethnic community sample of women. Sleep. 2008;31:979–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohayon MM. Severe hot flashes are associated with chronic insomnia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1262–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.12.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19:257–71. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824b970a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loprinzi CL, Sloan J, Stearns V, et al. Newer antidepressants and gabapentin for hot flashes: an individual patient pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2831–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:2057–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20:1027–35. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a66aa7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FDA approves the first non-hormonal treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause. www.fda.govUpdated: 2013 July 2 [cited 2013 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm359030.htm.

- 14.Evans ML, Pritts E, Vittinghoff E, McClish K, Morgan KS, Jaffe RB. Management of postmenopausal hot flushes with venlafaxine hydrochloride: a randomized, controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:161–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000147840.06947.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2059–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gambacciani M, Ciaponi M, Cappagli B, et al. Effects of low-dose, continuous combined hormone replacement therapy on sleep in symptomatic postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2005;50:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gursky JT, Krahn LE. The effects of antidepressants on sleep: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8:298–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Archer DF, Seidman L, Constantine GD, Pickar JH, Olivier S. A double-blind, randomly assigned, placebo-controlled study of desvenlafaxine efficacy and safety for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:172–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speroff L, Gass M, Constantine G, Olivier S. Efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine succinate treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:77–87. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000297371.89129.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19:848–55. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182476099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1058–66. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newton KM, Carpenter JS, Guthrie KA, et al. Methods for the design of vasomotor symptom trials: the Menopausal Strategies: finding lasting answers to symptoms and health network. Menopause. 2014;21:45–58. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31829337a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morin CM. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. Insmonia: psychological assessment and management. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith S, Trinder J. Detecting insomnia: comparison of four self-report measures of sleep in a young adult population. J Sleep Res. 2001;10:229–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, Sood R, Brink D. Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;281:991–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morin CM, Vallieres A, Guay B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:2005–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MT, Wegener ST. Measures of sleep: the Insomnia Severity Index, Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Diary (PSD), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:S184–S196. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, et al. Efficacy of brief behavioral treatment for chronic insomnia in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:887–95. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:733–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ensrud KE, Stone KL, Blackwell TL, et al. Frequency and severity of hot flashes and sleep disturbance in postmenopausal women with hot flashes. Menopause. 2009;16:286–92. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818c0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suvanto-Luukkonen E, Koivunen R, Sundstrom H, et al. Citalopram and fluoxetine in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms: a prospective, randomized, 9-month, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Menopause. 2005;12:18–26. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200512010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panay N, Ylikorkala O, Archer DF, Gut R, Lang E. Ultra-low-dose estradiol and norethisterone acetate: effective menopausal symptom relief. Climacteric. 2007;10:120–31. doi: 10.1080/13697130701298107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hays J, Ockene JK, Brunner RL, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on health-related quality of life. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1839–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen TF, Ravn P, Pitkin J, Christiansen C. Pulsed estrogen therapy improves postmenopausal quality of life: a 2-year placebo-controlled study. Maturitas. 2006;53:184–90. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R, Helenius H, Irjala K, Polo O. When does estrogen replacement therapy improve sleep quality? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1002–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70539-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diem S, Grady D, Quan J, et al. Effects of ultralow-dose transdermal estradiol on postmenopausal symptoms in women aged 60 to 80 years. Menopause. 2006;13:130–8. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000192439.82491.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carpenter JS, Storniolo AM, Johns S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trials of venlafaxine for hot flashes after breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12:124–35. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stearns V, Slack R, Greep N, et al. Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6919–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stearns V, Beebe KL, Iyengar M, Dube E. Paroxetine controlled release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2827–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freedman RR, Roehrs TA. Lack of sleep disturbance from menopausal hot flashes. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regestein QR. Hot flashes and sleep. Menopause. 2006;13:549–52. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227395.30321.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qaseem A, Snow V, Denberg TD, Forciea MA, Owens DK. Using second-generation antidepressants to treat depressive disorders: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:725–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-10-200811180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang M, Morin CM, Schaefer K, Wallenstein GV. Interpreting score differences in the Insomnia Severity Index: using health-related outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2487–94. doi: 10.1185/03007990903167415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]