Abstract

One of the most abrupt and yet unexplained past rises in atmospheric CO2 (>10 p.p.m.v. in two centuries) occurred in quasi-synchrony with abrupt northern hemispheric warming into the Bølling/Allerød, ~14,600 years ago. Here we use a U/Th-dated record of atmospheric Δ14C from Tahiti corals to provide an independent and precise age control for this CO2 rise. We also use model simulations to show that the release of old (nearly 14C-free) carbon can explain these changes in CO2 and Δ14C. The Δ14C record provides an independent constraint on the amount of carbon released (~125 Pg C). We suggest, in line with observations of atmospheric CH4 and terrigenous biomarkers, that thawing permafrost in high northern latitudes could have been the source of carbon, possibly with contribution from flooding of the Siberian continental shelf during meltwater pulse 1A. Our findings highlight the potential of the permafrost carbon reservoir to modulate abrupt climate changes via greenhouse-gas feedbacks.

Ice core records show evidence for an abrupt, and thus far unexplained, increase in atmospheric CO2 levels ~14,600 years ago. Here, the authors combine ice core data, a precisely dated decline in atmospheric 14C and numerical simulations, and propose thawing permafrost as a possible source of this event.

Ice core records show evidence for an abrupt, and thus far unexplained, increase in atmospheric CO2 levels ~14,600 years ago. Here, the authors combine ice core data, a precisely dated decline in atmospheric 14C and numerical simulations, and propose thawing permafrost as a possible source of this event.

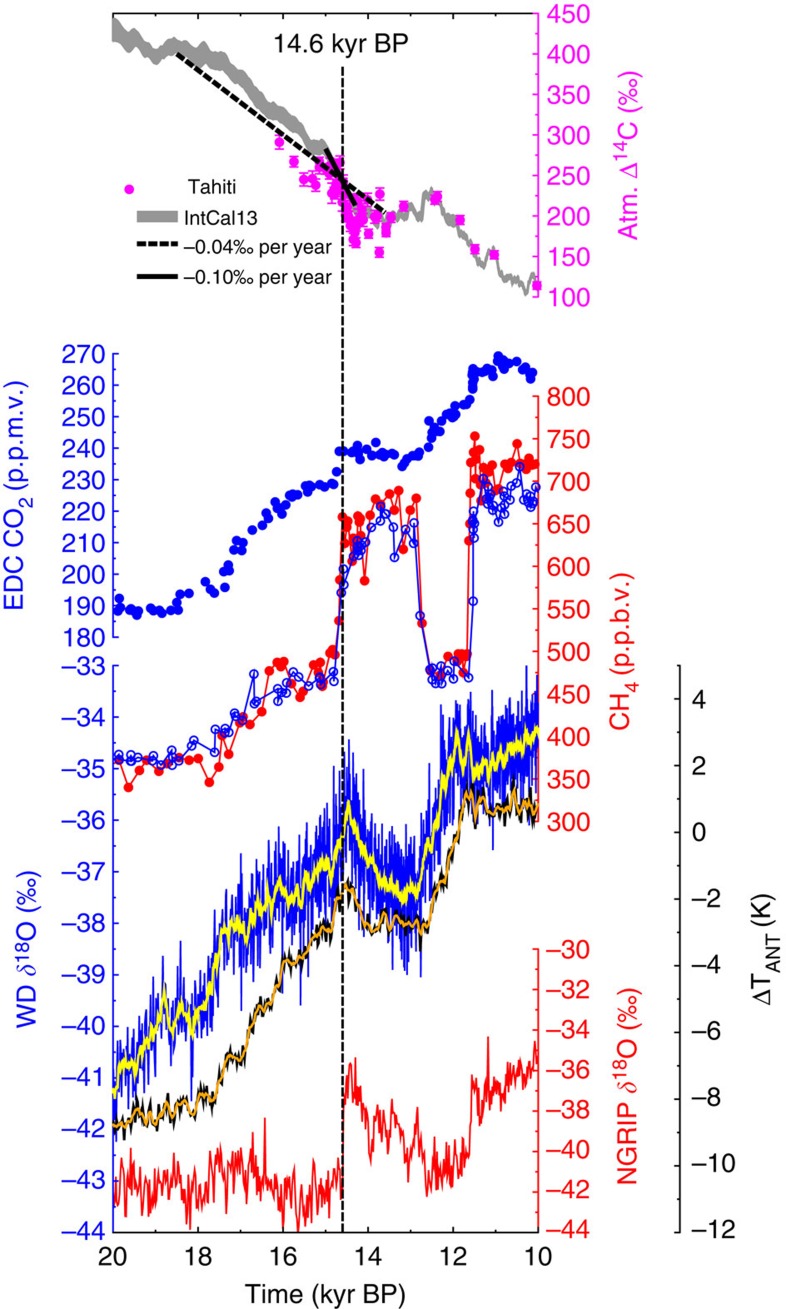

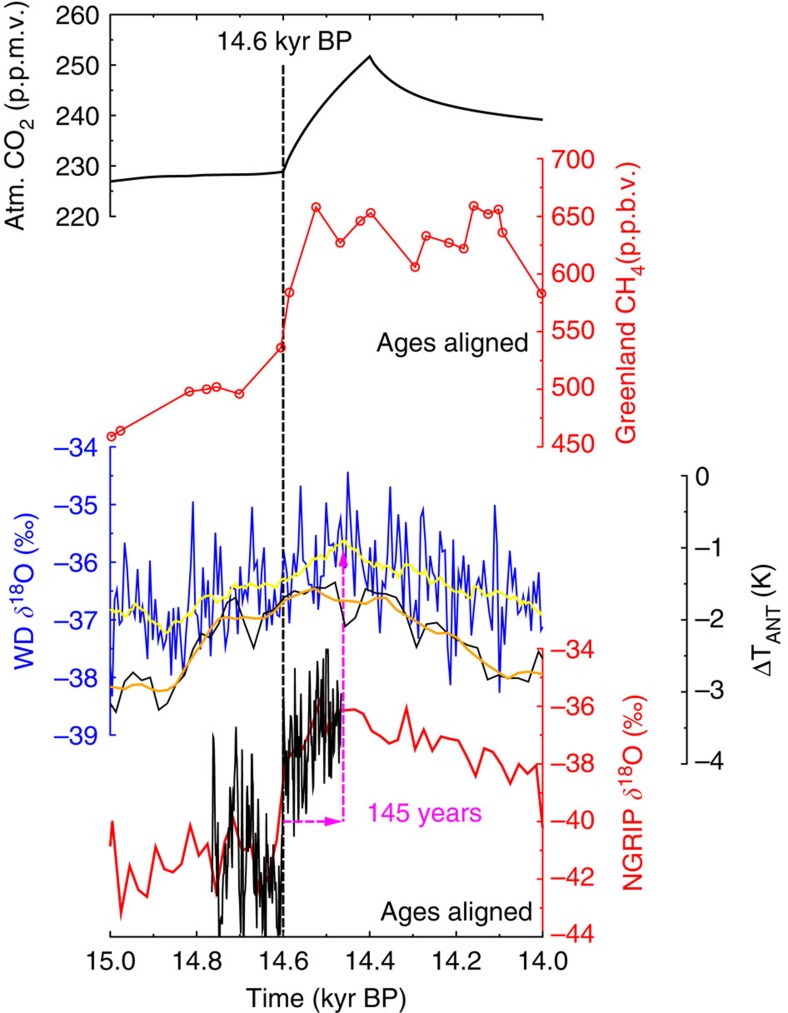

Changes in the global carbon cycle during the last deglaciation are so far not completely understood. However, based on the data and model-based interpretation, the emerging picture indicates that the rise in atmospheric CO2 of ~45 p.p.m.v. during the first half of the deglaciation (~1 p.p.m.v. per century) was probably fuelled by the release of old, 13C- and 14C-depleted deep ocean carbon1,2. The processes responsible for CO2 rise have changed dramatically with the beginning of the Bølling/Allerød (B/A) ~14,600 years before present (~14.6 kyr BP). Here the abrupt CO2 rise recorded in the EPICA Dome C (EDC) ice core3,4 was six times faster than before, about 10 p.p.m.v. in 180 years or ~6 p.p.m.v. per century (Fig. 1). Atmospheric CH4 rose by 150 p.p.b.v. between 18.5 and 14.6 kyr BP and then by the same amount again, but within centuries, around the onset of the B/A. The changes in both greenhouse gases (GHG) imply that a ratio of both changes ΔCH4/ΔCO2 is a factor of five larger around 14.6 kyr BP than during the previous four millennia. Such a change in the ratio ΔCH4/ΔCO2 might be the first indication that the wetlands identified5 as the main contributor to the rapid rise in CH4 at the onset of the B/A might also have contributed to the abrupt rise in CO2 at that time.

Figure 1. Relevant ice core and Δ14C data during Termination I.

Atmospheric Δ14C based on Tahiti corals (magenta circles, mean ±1σ)7 or IntCal13 (grey area, ±1σ uncertainty band around the mean)9, the latter including linear trends with −0.04‰ per year or −0.10‰ per year; CO2 from EDC (blue filled circles)1,22,68; CH4 from EDC (blue)22 and Greenland (red)69; WAIS Divide (WD) δ18O (original (blue) and 100 years running mean (yellow))54; stack of calculated temperature change3 ΔTANT from the five East Antarctic ice cores EDC, EPICA DML, Vostok, Dome Fuji and Talos Dome (original (black) and 100 years running mean (orange)); NGRIP70 δ18O. All Greenland records on GICC05 (ref. 23), all EDC records on AICC2012 chronology4, WD and ΔTANT on their own independent chronology.

Although this analysis of CH4 and CO2 changes gives some first ideas on the potential cause of the abrupt CO2 rise around the onset of the B/A, its ultimate source was so far not identified. The δ13C signature of terrestrial or marine carbon sources are different and might allow some source detection. However, the data uncertainty and density of the atmospheric δ13CO2 record did so far not allow such an identification6. A high-resolution U/Th-dated time series of atmospheric Δ14C derived from Tahiti corals7 over that event offers now some new and independent insights on the exact timing and magnitude of the carbon release event and brings some suggestions on its potential origin.

Here we show that the synchronous change in atmospheric Δ14C and CO2 derived from the Tahiti and EDC data sets at the onset of the B/A can be explained by the same process and suggest permafrost thawing being this process. We finally examine the climate impact of the GHG changes around 14.6 kyr BP using a state-of-the-art-coupled Earth system model. Special focus of these investigations is the imprint of the GHG changes on the Antarctic temperature signature and the relevance of these changes for the interpretation of bipolar climate linkages during abrupt climate changes8.

Results

Atmospheric Δ14C and ice core CO2

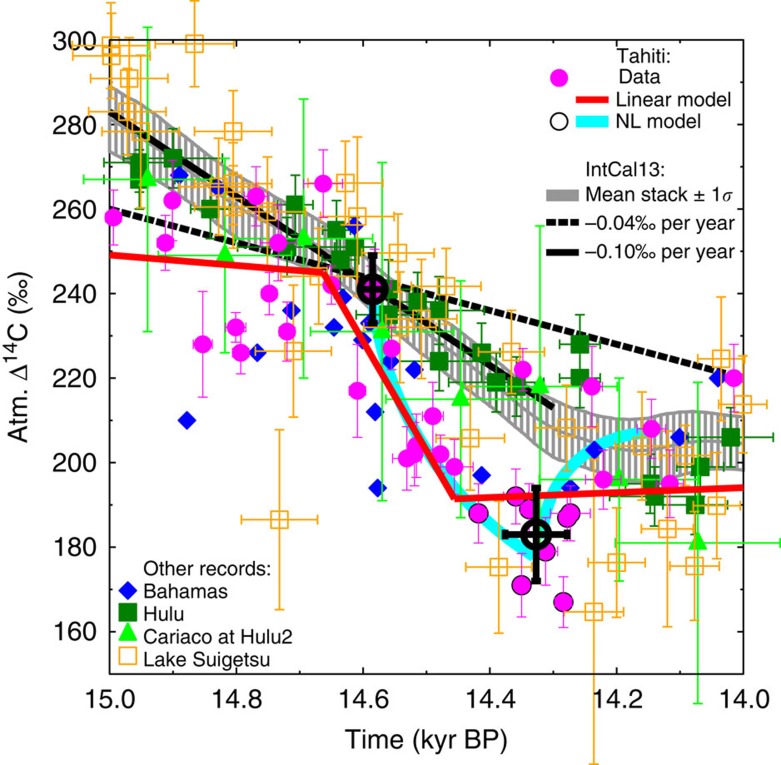

The new coral-based atmospheric Δ14C record from Tahiti7 shows a prominent decline around 14.6 kyr BP, an anomaly not visible in the IntCal13 Δ14C stack9 (Fig. 2). For comparison, we briefly discuss specific details related to IntCal13 and what other 14C archives record at that point in time: After 13.9 kyr BP IntCal13 is based on tree rings with very little variability. For older samples, however, the various archives differ by more than the measurement errors. A Δ14C anomaly similar to the Tahiti data can be seen in speleothems from Bahamas10 (Fig. 2). The anomaly is not seen in speleothems from the Hulu Cave11 or in the marine sediments from Cariaco12 (Fig. 2). The Cariaco record bears some problems—therefore, a part of it has been excluded by the IntCal13 group specifically during the Heinrich 1 event, that is, just before the B/A9. Necessary corrections of speleothem 14C data for its dead carbon fraction (DCF) introduce large uncertainties to atmospheric Δ14C based on them9. Furthermore, the DCF is not constant but depends itself on climate13 making the speleothems an archive difficult to interpret, especially during rapid climate changes. The signal might thus potentially be smoothed out in Hulu, as the DCF acts as a low-pass filter. The best recorder of atmospheric Δ14C available up to now might be the terrestrial plant material derived from Lake Suigetsu14. Here no corrections for the reservoir effect or for DCF are necessary. The Lake Suigetsu data, however, are rather scattered over the time interval of interest, show a steeper decline in Δ14C than IntCal13, but neither strongly support IntCal13 nor Tahiti (Fig. 2). Altogether, the evidences from Δ14C data are mixed and further data are necessary for a conclusive interpretation.

Figure 2. Data analysis of atmospheric Δ14C around 14.6 kyr BP.

Atmospheric Δ14C based on Tahiti corals7 (magenta circles) and IntCal13 (grey line, ±1σ uncertainty band around the mean)9 are analysed for trends and compared with various other archives (speleothems from Bahamas10 (blue diamonds), Hulu Cave11 (dark green squares), marine sediments in Cariaco12 (light green triangles) plotted on revised Hulu2 age model9, Lake Suigetsu14 (orange open squares)). All individual data points are plotted with ±1σ in both age and Δ14C. IntCal13 was approximated by a linear trend with either −0.04‰ per year (black solid line) or −0.10‰ per year (black dashed line). Tahiti data were analysed for break points with two different models (see Methods). For the linear model (red lines), a statistical package was used. For the non-linear (NL) model (cyan lines), two data points at beginning of the Tahiti data Δ14C anomaly from the IntCal13 data and the eight points around the local minimum (black open circles) were averaged, plotted with ±1σ in both age and Δ14C (bold large black open circles) and further analysed. The anomaly in the Tahiti Δ14C data following the linear model is Δ(Δ14C)=−54±8‰ in Δ(age)=207±95 years and following the NL model: Δ(Δ14C)= −58±14‰ in Δ(age)=258±53 years.

The coral-based Δ14C record from Tahiti is corrected for a reservoir age15 of constantly 300 14C years7 to be interpreted as atmospheric Δ14C. In principle, the reservoir age might change over time, mainly due to ocean circulation changes. However, simulations with three different models16,17,18 suggest that the reservoir age is relatively stable in the central Pacific around Tahiti for various ocean circulation changes (see Supplementary Note 1 for details). We therefore assume that reservoir ages did not change over the last 15 kyr in the central low-latitude Pacific and the Δ14C signal based on Tahiti corals is not based on local effects but indeed a recorder of atmospheric Δ14C changes.

We date the start of this Δ14C decline seen in the Tahiti data with two different approaches (Fig. 2, methods) with a 1σ uncertainty of less than a century to 14.6 kyr BP and calculate a Δ14C decline of ~55‰ within 200 to 250 years. Having already excluded changes in reservoir age, we are left with either a modified carbon cycle or reduced 14C production rates as potential process explaining the Tahiti Δ14C data. On the basis of available 10Be, data changes in 14C production rates cannot convincingly explain the Δ14C data (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Note 1). All our tests therefore indicate that the Tahiti Δ14C drop at 14.6 kyr BP is caused by carbon cycle changes. This is our working hypothesis on which all else is based on, but note that its failure cannot entirely be ruled out.

Carbon cycle changes responsible for the Δ14C anomaly would also leave their imprints on atmospheric CO2. We can therefore use the absolute U/Th-dated Δ14C from the Tahiti corals as an independent time constraint on the atmospheric CO2 rise. This is a novel new approach to synchronize atmospheric Δ14C and atmospheric CO2, because ice cores archive only a smoothed version of the atmospheric concentrations making an exact dating of the abrupt change in atmospheric CO2 very difficult6. Furthermore, firnification and gas enclosure are still not completely understood19, and the age difference between ice matrix and embedded gases complicates gas chronologies3. On the most recent chronology4, AICC2012, CO2 measured in situ in the EDC ice core rises by 10 p.p.m.v. between 14.81 and 14.68 kyr BP. This is more than a century faster when compared with previous chronologies3 (Figs 3a and 4b), but might in detail be revised even further once the most recent understanding of firnification is applied20. Atmospheric changes in CO2 need to have happened even more abruptly than what is recorded in ice cores6.

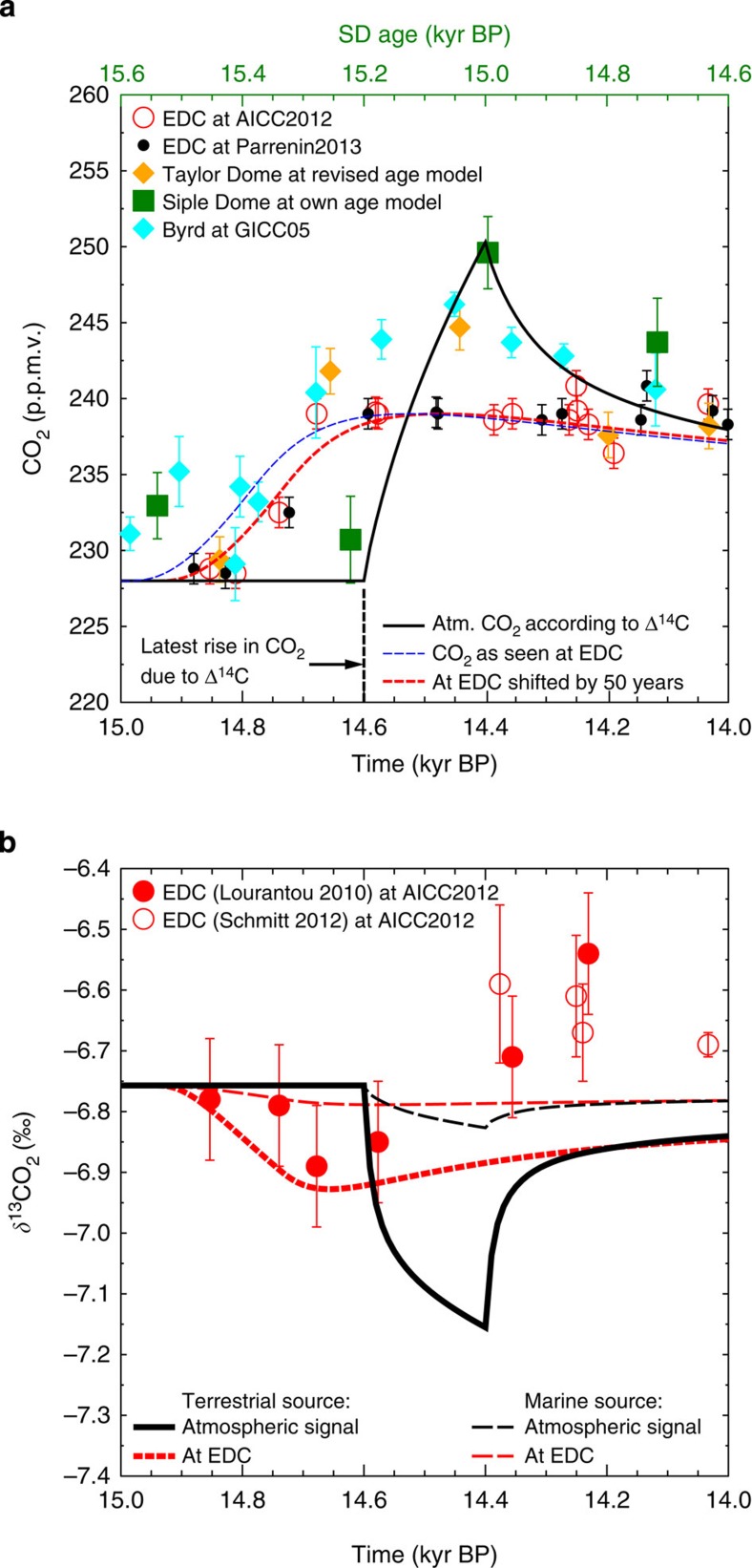

Figure 3. Ice core and simulated true atmospheric CO2 and δ13CO2.

(a) Ice core CO2 data (±1σ) from EDC1,22,68 on two different chronologies3,4 AICC2012 and Parrenin2013, Taylor Dome on revised age model26,27, Siple Dome on own age model (top x axis)27, Byrd on age model GICC05 (refs 25, 28). Simulated true atmospheric CO2 in our best-guess scenario according to 14C data (black bold line), filtered to a signal that might be recorded in EDC (blue dashed line), shifted by 50 years to meet the EDC data (dashed red line). (b) Ice core δ13CO2 data (±1σ) from EDC1,68, simulated true atmospheric δ13CO2 of our best-guess scenario and how it would have been recorded in EDC for either terrestrial or marine origin of the released carbon, implying a δ13C signature of −22.5 or −8.5‰, respectively.

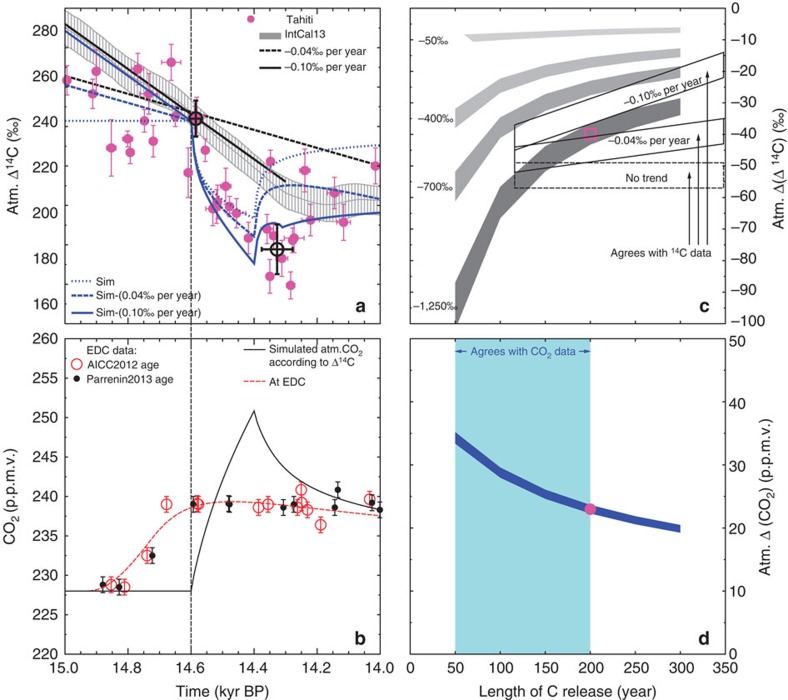

Figure 4. Main carbon cycle simulation results.

The transient simulation results (left) showing the impact of a carbon release event on true atmospheric Δ14C and CO2 obtained with the carbon cycle model BICYCLE for the best-guess scenario are compared with the data. In sensitivity studies (right), the length of the release event and the radiocarbon signature Δ(Δ14C) of the released carbon are constrained by the data. (a) Atmospheric Δ14C data from Tahiti corals7 (magenta, mean ±1σ in both age and Δ14C) and IntCal13 (ref. 9) (grey band, mean ±1σ) data. Black bold circles denote start and stop (±1σ) of carbon release in the non-linear model of the Tahiti data interpretation. The vertical black dashed line marks the estimated started of carbon release at 14.6 kyr BP based on a combination of different explanations. Best-guess simulation results of atmospheric Δ14C (blue) superimposed by a linear trend of either −0.04‰ per year (long dashed line) or −0.10‰ per year (solid line) (short dashed: no trend superimposed). (b) Atmospheric CO2. EDC ice core CO2 data (mean ±1σ) on two different chronologies3,4 AICC2012 and Parrenin2013. Simulated true atmospheric CO2 rise (black bold line), and how the signal might be recorded in EDC (dashed red line) after filtering for gas enclosure and shifted by 50 years to meet the data. (c) Simulated peak height in atmospheric Δ14C (grey areas) as function of length of carbon release and of the Δ14C depletion. (d) Simulated peak height in atmospheric CO2 (dark blue area) as function of length of carbon release. In c,d, simulations result with the AMOC in either a weak or a strong mode are combined spanning a range of results. Magenta square and circle in c,d mark results of our best-guess scenario for Δ14C and CO2, respectively. We colour coded the areas in the parameter space where simulation results agree with the EDC CO2 data (d, light blue) and with the interpretation of the Tahiti Δ14C data (c, black boxes). The latter are modified for background linear trends already contained in IntCal13 based on other processes.

Here we use the Tahiti Δ14C as an independent age constraint for the start of the carbon cycle changes (14.6 kyr BP). Recently, others21 have shown that the rise in atmospheric CH4 and in temperature in Greenland are near synchronous (5±25 years) at the onset of the B/A warming. From previous GHG records measured at the EDC ice core22, it is known that CO2 and CH4 also rise synchronously at 14.6 kyr BP. Combining this information, we have to conclude that the rise in atmospheric CO2 and CH4 together with the rapid warming of the northern hemisphere (NH) happened at the same time, and started at 14.6 kyr BP. This is only 35 years later than the suggested age of the onset of the B/A (14.635±0.186 kyr BP, ±1σ) in the annual-layer counted NGRIP ice core23,24, well within the dating uncertainty of GICC05 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Implication on the timing of abrupt climate change as obtained in various ice core records from Greenland and Antarctica.

Our results suggest that anomalies in Tahiti Δ14C and true atmospheric CO2 are caused by the same process. This information is used here as an independent age constraint. The onset of the abrupt rise in atmospheric CO2 (black bold, this study) is thus tied to 14.6 kyr BP. From previous ice core analysis22, it is known that the rise in CO2 and CH4 (red circles, Greenland composite69) occur synchronously here. A new study21 on the NEEM ice core tied the CH4 rise to be near synchronous to Greenland temperature rise. This synchronicity of the start of the abrupt changes in atmospheric CO2, CH4 and Greenland temperature tied to 14.6 kyr BP led to the age alignments in CH4 and NGRIP δ18O (high24 (black thin line) and low70 (red line) resolution). We furthermore show some Antarctic climate records on their own independent chronologies to illustrate the temporal north–south offsets. WD54 δ18O, original (blue) and 100 years running mean (yellow) and stack3 of temperature change from five ice cores in East Antarctica, ΔTANT, original (black) and 100 years running mean (orange).

Carbon cycle simulations

A release of 125 Pg of C into the atmosphere within a time window of 50 to 200 years was proposed before6 to explain the rise of 10 p.p.m.v. in CO2 measured in EDC. The true atmospheric CO2 then shows an overshoot whose peak amplitude mainly depends on the length of the assumed release time (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, low-resolution CO2 time series from other ice cores with amplitudes of 17, 15 and 19 p.p.m.v. in Byrd, Taylor and Siple Dome, respectively25,26,27,28 (Fig. 3a), indicate that the true atmospheric signal had a larger amplitude than what was measured in situ in EDC6.

In our previous analysis, we also investigated atmospheric δ13CO2, from which the potential source of the released carbon might have been identified. The new compilation of ice core δ13CO2 data published in the mean time1 offers a new look on the information contained in that record. This δ13CO2 compilation is now based on data from EDC, EPICA DML and Talos Dome. In our time window of interest (15–14 kyr BP), however, only data from EDC were obtained with some new data points adding to the previous record. This revised δ13CO2 record shows a drop by 0.1‰ around 14.7 kyr BP followed by a subsequent rise by ~0.2‰ at 14.4 kyr BP (Fig. 3b). Distinguishing terrestrial from marine carbon sources for our carbon release leads in our best-guess scenarios (see below how that was chosen) to either a drop in δ13CO2 of 0.4‰ or less than 0.1‰ in the true atmospheric signal, respectively, but only to −0.15‰ and less than −0.05‰ in a time series that would be recorded in EDC (Fig. 3b). Both marine- and terrestrial-based δ13CO2 simulations fall within the uncertainties of the measurements before 14.6 kyr BP. The small rise in δ13CO2 after 14.4 kyr BP, however, indicates that directly after the onset of the B/A other processes released less δ13C-depleted carbon to the atmosphere, for example, CO2 outgassing from warm oceanic surface waters. On the basis of the data uncertainty of δ13CO2 in EDC, it is still impossible to clearly identify if the released carbon was of marine or terrestrial origin.

Using the same carbon cycle model6, we repeat simulations of carbon release with special focus on 14C. The model dynamic with respect to 14C was extensively evaluated (Supplementary Note 2). We assume a depletion in 14C of the released carbon with respect to the atmosphere (Δ(Δ14C)) between −50 and −1,250‰. This range in the 14C anomalies covers carbon sources from the mean terrestrial biosphere potentially released by shelf flooding6 (−50‰), suggested signatures of old carbon of Pacific intermediate waters as measured off Baja California29 (−400‰) and Galapagos30 (−700‰) to a maximum effect of 14C-free carbon (−1,250‰). The Shelf Flooding Hypothesis is explained in detail in the next section, and some more details on our assumptions on 14C are found in the methods.

The highest-simulated anomalies in atmospheric Δ14C are obtained for short release times reaching −100‰ for 50 years and the largest Δ(Δ14C) of −1,250‰ (Fig. 4c). The amplitudes drastically decline with longer release time towards less than −35‰. Δ14C anomalies are significantly smaller if Δ(Δ14C) was −700‰ or less (Fig. 4c). Because of the distinct dynamics of the Δ14C data, release times shorter than ~110 years are at odds with the Tahiti 14C reconstruction. Simulated anomalies in atmospheric carbon records are nearly identical for Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) in the strong or weak mode (Methods, Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 3). Combining the information from both the ice core data and our analysis of the Tahiti Δ14C data leads to a range of scenarios with carbon release times between ~110 and 200 years in which model results and data agree (Fig. 4c). The range of possible scenarios fulfilling the data constraints also includes some with Δ(Δ14C) between −700 and −1,250‰, and so we cannot entirely exclude the possibility that the released carbon still contains some 14C. From these possible scenarios, we selected the one with the longest release time of 200 years to be our best-guess scenario, because short release times lead to higher amplitudes in atmospheric CO2, which are not supported by other ice core data. This scenario pinpoints to a Δ(Δ14C) of −1,250‰ resulting in peak amplitudes of −42‰ in atmospheric Δ14C (Fig. 4c) and of +22 p.p.m.v. in atmospheric CO2 (Fig. 4d). The depletion in 14C necessary for the model output to agree with the data implies that the shelf flooding hypothesis connected with meltwater pulse 1A (MWP-1A)6,31 seems at a first glance to be in disagreement with the Tahiti-based atmospheric Δ14C reconstructions (Fig. 4c). We discuss details on a potential contribution connected with MWP-1A further below. The release of deep ocean carbon, although so far not suggested to play a role during this rapid CO2 rise, might only potentially be responsible here, if water masses are detected, which are even more depleted in 14C than what is known until now29,30.

The Tahiti Δ14C data show an excursion from the long-term declining trend of IntCal13 (ref. 9) (Figs 1 and 4a). Depending on the time window of interest, IntCal13 might be approximated by a linear fit with a slope of −0.04‰ per year (the whole Mystery Interval, 19–14 kyr BP) or −0.10‰ per year (15.0–14.3 kyr BP), respectively. These long-term changes are probably caused by a mixture of changes in 14C production rate and the carbon cycle32. While we are able to force our model with changing 14C production rates (Supplementary Fig. 4), all relevant processes in the carbon cycle are not yet identified. We therefore compare the Δ14C data with our original simulation results based on constant 14C production rate, but also with some results that are corrected for the trend seen in IntCal13. If corrected accordingly, our best-guess scenario finally meets the amplitude in the Tahiti Δ14C data (Fig. 4a,c).

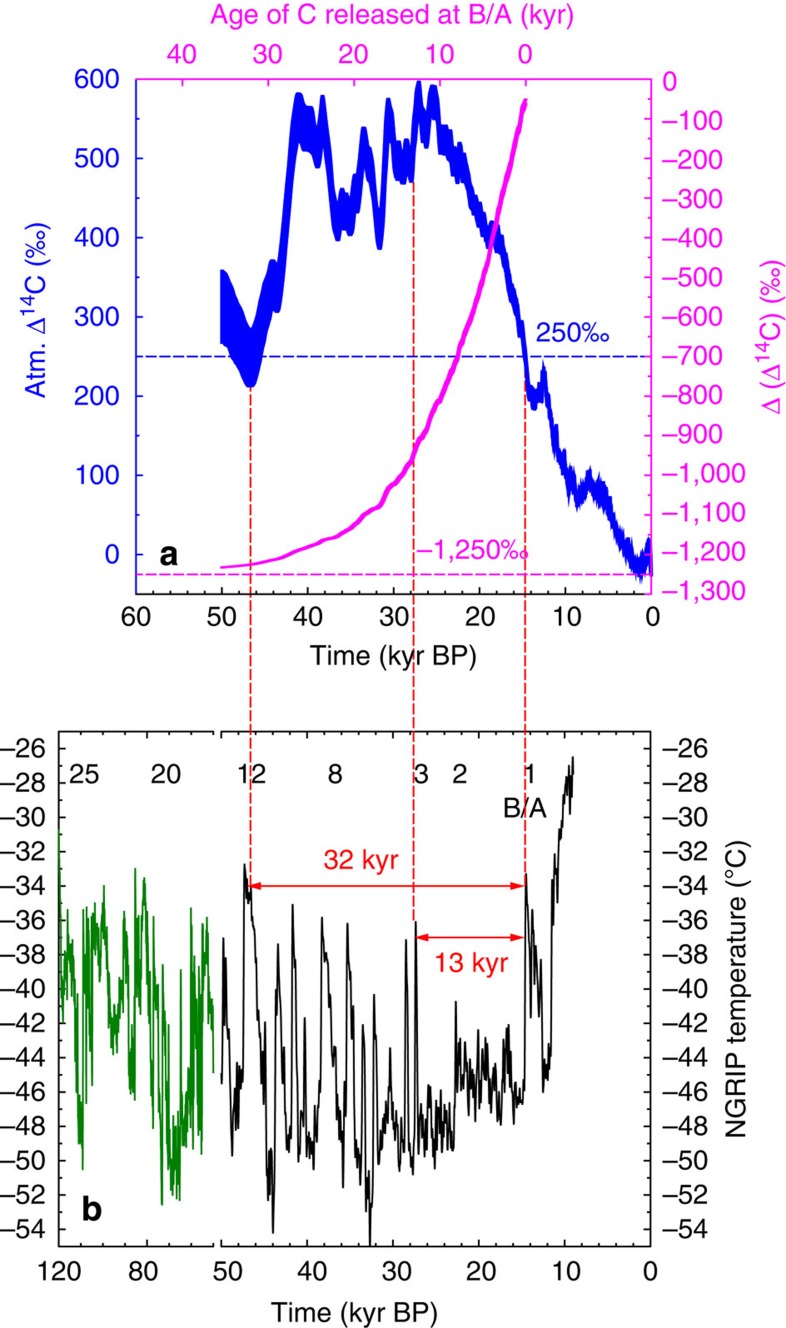

Evidence for permafrost thawing

The synchronicity of the NH warming and the carbon cycle change together with our suggested hypothesis for the injection of nearly 14C-free carbon into the atmosphere make permafrost thawing and a subsequent release of old soil carbon a prominent candidate to explain the atmospheric carbon records. The age of carbon stored in permafrost soils during glacial times is unknown. Throughout the last glacial cycle Greenland and the whole NH was perturbed by the rapid warming of Dansgaard/Oeschger (D/O) events33. However, during the last 80 kyr, only D/O event 12 around 47 kyr BP reached in a temperature reconstruction for the site of the NGRIP ice core in Greenland similar high temperatures as the B/A (Fig. 6b). In this NGRIP, temperature time series D/O event 2 around 23 kyr BP was rather weak and short, but D/O event 3 at 28 kyr BP reached with −36 °C nearly the temperature of −33 °C of the B/A33 (Fig. 6b). We assume that most of the NH follow this temporal changes in temperature observed for Greenland, although with warmer temperatures closer to the freezing point further south. It might then be that large areas of the NH were permanently frozen after D/O event 3, thus about 13 kyr before thawing induced by the onset of the B/A. The Δ14C of that permafrost carbon would be depleted by −900‰ with respect to atmospheric Δ14C during release around 14.6 kyr BP (Fig. 6a). However, soil carbon might age significantly in high latitudes before freezing, for example, present day North American peatlands are up to 17-kyr old34. Such soil ageing reduces 14C even further. If the precursor material of the permafrost soil carbon was photosynthetically produced during D/O event 12 around 47 kyr BP (the next preceding period comparable in temperature to the B/A, Fig. 6b), it would be essentially free of 14C and depleted with respect to atmospheric Δ14C by nearly −1,250‰ (Fig. 6a). Permafrost thawing would then contain a depletion in Δ14C, which is more negative than for all other suggested processes6,29,30. An alternative scenario based on the destabilization of gas hydrates, which also contain 14C-free carbon, can be rejected based on CH4 isotopes35,36,37.

Figure 6. Radiocarbon depletion of soil carbon of different age and high northern latitude climate change.

(a) Atmospheric Δ14C based on IntCal13 (ref. 9) over the last 50 kyr (blue, left y axis, mean ±1σ). Calculated radiocarbon depletion resulting in Δ(Δ14C) (mean ±1σ) of soil carbon released during the B/A as a function of its age (magenta, right y axis, upper x axis) and of atmospheric Δ14C during time of production. (b) NGRIP temperature reconstruction33 from 120 to 10 kyr BP. The time series is plotted in two different colours because of the break in the x axis scale at 50 kyr BP. Numbers label selected D/O events. Red labelled arrows highlight the time which past since NGRIP was similar as warm as during the B/A (32 kyr since D/O event 12) and since the previous significant warming before the B/A (13 kyr since D/O 3).

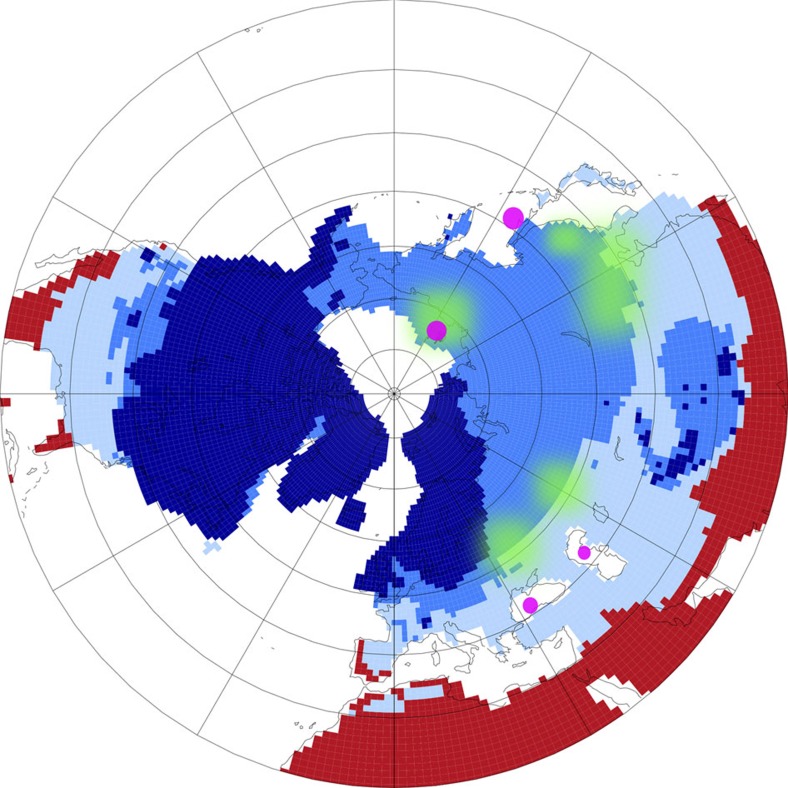

For the present day, a rise in global mean temperature by 5 K, which because of polar amplification might represent a northern high latitude warming of 10 K, was proposed to lead to the release of more than 130 Pg of soil carbon from permafrost thawing within 200 years38. Greenland ice core data33 and simulations39 suggest that temperatures in the B/A rose by 10–15 K to near preindustrial levels in central Greenland and throughout most of the NH land areas. A large inert terrestrial carbon pool consisting of permafrost soils containing 700 Pg more C at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) than at present day has been proposed40, which needs to release its excess carbon during deglaciation. The areal extent of continuous permafrost at LGM (Fig. 7) was calculated from models41 in PMIP3 to 26 × 1012 m−2, agrees with reconstructions42, and is twice as large as for preindustrial times41.

Figure 7. PMIP3 simulation results on the LGM permafrost extend.

Results41 show a polar projection of the NH from 20 °N northwards, are based on soil temperature and distinguish land with ice (dark blue), permafrost (blue), seasonal frozen (light blue) and not frozen (red). Present day coastlines are sketched in thin black lines. Magenta points mark potential core sites (Siberian Shelf, Black Sea, Caspian Sea, Sea of Okhotsk) from which future 14C measurements on terrigenous material might verify the age of permafrost possible thawed around 14.6 kyr BP (suggested green areas).

Previously, methane isotopes36 suggested that a rise in boreal wetland CH4 emissions by +32 Tg CH4 per year would explain the CH4 rise into the B/A. These findings36 have been challenged by new methane isotope data37, but so far no revised CH4 emissions from boreal wetlands have been calculated for the B/A. An alternative interpretation5 of the CH4 cycle based on its interhemispheric gradient suggests that the rise in CH4 by 150 p.p.b.v. at the onset of the B/A was largely driven by the increase in CH4 emissions from both tropical (+35 Tg CH4 per year) and boreal (+15 Tg CH4 per year) wetlands. The CH4 change at the onset of the B/A is thus clearly dominated by tropical wetlands and its conclusive interpretation is beyond the scope of this study. However, the rise in CH4 emissions from boreal wetlands is nearly identical to the rise in emissions of up to +14 Tg CH4 per year projected from deep permafrost thawing of the next century43. If this rise in the boreal CH4 flux is integrated over the 200-year time window of our carbon release scenario, a total of 3.0 Pg of CH4 (or 2.25 Pg C in the form of CH4) might have been released. This is ~2% of our total estimated carbon emissions of 125 Pg C, and in line with an expert assessment on the future vulnerability of permafrost44 estimating that 2–3% of carbon released by thawing might enter to the atmosphere in the form of CH4. Although the contribution from boreal wetlands to the CH4 rises at the onset of the B/A is small, the nearly 14C-free signature connected with our proposed permafrost thawing might be tested by 14C measurements on CH4 derived from ice cores45.

So far, we suggested that NH permafrost is the responsible source of the released carbon. In the following, we hypothesize which region might have been affected in detail by permafrost thawing and how this can be tested in future studies. The PMIP3-based map on the LGM permafrost extent clearly indicates that the largest areas with continuous permafrost are found in northern Siberia (Fig. 7). Thus, evidences of permafrost thawing connected to the NH warming should be expected in outflow originated from the southern edge of the LGM permafrost area (around 40–50°N), which thawed first. A lot of these areas are drained via the Amur river into the Sea of Okhotsk and into coastal seas towards the south (Caspian and Black Sea). Indeed, a combination of terrestrial biomarkers that clearly indicate the thawing of permafrost was found at the onset of the B/A in a sediment core drilled in the Black Sea that records the drainage from the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet46. Here variations in the normalized concentrations of different long-chain molecules provide information on changes in the abundance of peat-forming plants. Such data are useful indicators for the variation of permafrost thawing and of wetland extension as well as for fluvial periglacial soil erosion in its drainage basin. In details, this study46 provides evidence that the permafrost melting was very intense only during the initial part of the Bølling corresponding indeed to the sharp NH warming.

The map (Fig. 7) also shows that a large fraction of the Siberian shelf in the Arctic Ocean was during the LGM covered by permafrost. It might thus be possible that MWP-1A, which was recorded as a rise in sea level at Tahiti31 from about −105 to −85 m between 14.65 and 14.31 kyr BP might be partially responsible for the carbon release as initially suggested6. The flooding of continental shelves was also proposed to contribute to the CH4 rise during deglaciation and during D/O events47. In our earlier study6, we proposed that mainly the flooding of the Sunda Shelf followed by tropical rain forest decay might have been responsible for the carbon release. This shelf flooding scenario was here addressed with a Δ(Δ14C) of −50‰ for mean terrestrial carbon, which failed to meet the Δ14C data. In our earlier study6, we also discussed that the existing time series of sea level change suggest that before MWP-1A the shelves were last flooded around 30 kyr BP, 15 kyr earlier, leaving ample time for 14C in permafrost carbon on the shelf to decay and to produce a Δ(Δ14C) in the released carbon of down to −900‰ (Fig. 6). Most recent sediment data48 on iceberg discharge in Antarctica during Termination I found a significant Antarctic contribution to MWP-1A. Fingerprint analysis49 of different water sources for MWP-1A indicate that sea level would rise locally by up to 50% above global average on the Siberian Shelf for freshwater released in Antarctica. When considering the source-depending overprint49, we calculate, based on the present day bathymetry50, a maximum areal extent of 0.4 × 1012 m−2 of the Siberian Shelf, which might have been flooded by MWP-1A. This is the same order of magnitude as the present day Siberian Yedoma deposit extent51 from which an organic carbon content of 30–140 Pg C has been proposed51. Coastal erosion and sub-sea permafrost release in Arctic Siberia are also observed for modern times52 with a Δ14C signature of the released organic carbon as low as −800‰. Modern organic carbon content in Eurasian Arctic53 river runoff have Δ14C ages of up to 10 kyr. All these modern data indicate that old carbon in permafrost exists nowadays, and potentially was more abundant and older during glacial times.

In which region the thawing of permafrost finally happened might be verified by future 14C measurements on terrigenous organic material that are retrieved from marine sediments in the suggested coastal seas. It will then be possible to finally attribute the size of the released carbon to either a pure thermodynamically thawing at the southern edge of the permafrost area or to a contribution from flooding the Siberian Shelf during MWP-1A.

Discussion

The rapid CO2 rise at the onset of the B/A is contained with different amplitude in various ice cores (Fig. 3a). However, the uncertainty in the proposed age distribution of the CO2 in EDC is still large6 (Supplementary Fig. 2c) and the assumed carbon release history and the applied carbon cycle model influence the amplitude of the proposed true atmospheric CO2 rise. Future CO2 measurement from the WD ice core54 might refine some of these aspects. The WD ice core has an order of magnitude higher present day accumulation rate than EDC (20 versus~3 g cm−2 per year), thus offers temporally higher resolved gas records. A potential WD CO2 record still needs to be corrected for the smoothing during firn enclosure, although this effect will be a lot smaller than for EDC. Only by considering the 20% uncertainty in the mean exchange time of CO2 before enclosure in EDC (Supplementary Fig. 2c) would result in a CO2 release and an amplitude in the true atmospheric CO2 rise, which are also 20% smaller than in our best-guess scenario, for example, releasing 100 instead of 125 Pg C leading to a true atmospheric CO2 amplitude of 18 instead of 22 p.p.m.v. (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Results are then still within the range given by the EDC CO2 data (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Furthermore, we calculate that a 33% reduction in the proposed carbon released to the atmosphere (85 instead of 125 Pg C) still fulfils the data constrains given by the Tahiti Δ14C record.

Other rapid CO2 rises are detected in EDC at the end of the Younger Dryas and in Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 3 in other ice cores55. Whether they are also caused by permafrost thawing is not investigated here. However, these other rapid CO2 jumps are not always connected to a warming of the NH. Furthermore, the missing of 14C-depleted CH4 during the CO2 rise at the end of the Younger Dryas around 12 kyr BP45 suggests that other processes are responsible. Moreover, our suggested old soil carbon release during permafrost thawing at 14.6 kyr BP, requires that the same carbon sources were not tapped during other events within Termination I. Again, 14C measurements on terrigenous material might clarify how old the carbon released from permafrost was or if earlier CO2 rises might already have consumed the old, 14C-depleted carbon.

Our study suggests that for Termination I, abrupt warming in the NH might lead to massive permafrost thawing, activating a long-term immobile carbon reservoir. The abruptly released carbon then amplified the initial warming as a positive feedback. Our best-guess scenario generates together with the rise in the other two important GHG CH4 and N2O a radiative forcing6 of ~0.7 W m−2. It is important to quantify the feedback of this GHG forcing on climate to better understand the impact of the abrupt GHG changes during the last deglaciation. Since the abrupt GHG changes are contemporaneous with the onset of the B/A (in the North) and the beginning of the ACR (in the South), the sequence of the associated bipolar climate linkages are of particular interest.

Therefore, we have conducted transient simulations with our best-guess reconstruction of atmospheric GHG changes during the beginning of the B/A and the ACR, using the Earth System Model COSMOS16,56 in a coupled atmosphere-ocean configuration as outlined in detail in the Supplementary Note 3. To evaluate the global impacts of the GHG changes it is instructive to analyse Antarctic temperature changes, since temperature changes obtained from Antarctic ice cores have been shown to reflect global scale climate changes associated with CO2 variations particularly well57. On the basis of our climate model investigations, we find that the abrupt rise in GHG concentrations provides an important impact on the Antarctic temperature signature associated with an abrupt AMOC strengthening at the end of Heinrich Stadial 1 (Supplementary Fig. 5). This highlights a potential contribution of abrupt GHG changes on the bipolar climate signature during deglaciation. In this sense, the abrupt GHG changes would be a factor that would offset the timing of the temperature maximum leading into the ACR, compared to the onset of the B/A. As layed out in detail in the climate feedback section of the Supplementary Note 3, also smaller GHG spikes bear the potential to have a substantial effect on the Antarctic temperature response when compared with impacts caused by AMOC changes.

So far a synthetic record of Greenland temperature changes8 seems to indicate that rapid climate changes in the north might indeed have been a universal feature of deglaciations during the last 800 kyr. Hence, similar to the last deglaciation, abrupt permafrost thawing might have also occurred regularly during earlier terminations, although further studies are necessary here. Termination II also contains58 an abrupt rise in CO2, synchronous to a rise in CH4. A massive drop in atmospheric δ13CO2 accompanying this event58 is consistent with the release of δ13C-depleted CO2 that might indicate a terrestrial source. However, new δ13CO2 data59 did not confirm this negative δ13CO2 anomaly and the revised data give no indication on the source of this CO2 rise. A synchronous change in deuterium excess60, a proxy for moisture source shifts, has been used to suggest that abrupt shifts in southern westerlies might be connected with the CO2 rise61, but a compelling explanation remains elusive and further testing of permafrost thawing as a possible alternative interpretation is needed.

In conclusion, we here suggest that the processes responsible for the abrupt CO2 rise at the onset of the B/A is also the underlying cause for the drop seen in atmospheric Δ14C based on Tahiti corals. This connection offers a U/Th-dated tie point for the start of the massive release of carbon at 14.6 kyr BP. Using a carbon cycle box model, and assuming the release of 125 Pg of nearly 14C-free carbon, we are able to explain observed anomalies in atmospheric CO2 and Δ14C. On the basis of the 14C signature of the released carbon and the synchronicity to the warming of the NH, we suggest that the thawing of permafrost was this responsible process. A potential contribution from MWP-1A flooding the Siberian Shelf, which might have contained a large amount of permafrost, is also possible. Future 14C measurements on terrigenous material might further constrain the source region. Our interpretation not only provides conceptual insights into the source of the excursions in the atmospheric carbon records around 14.6 kyr BP, but also offers an alternative to explanations62,63 for the interhemispheric timing of the B/A and the ACR as found in ice cores from both hemispheres. Taken together, our findings highlight a potential climate feedback that might be obtained from abrupt CO2 release during deglaciation. This analysis furthermore indicates that the proposed carbon cycle feedback from an anthropogenic driven permafrost thawing in the near future38,43,44,64 may already have happened in a similar way in the past.

Methods

Analysis of the Δ14C data

For analysis of the drop in the atmospheric Δ14C data based on Tahiti corals, we used two different approaches (Fig. 2). First, we used a linear statistical model Breakfit65, which calculates the break points in time series. Breakfit searches for two linear functions that are joined at the break point. To determine the break points, the model is fitted to the data applying an ordinary least-squares method with a brute-force search for the break points. A measure of the uncertainty of the break points is based on 2,000-block bootstrap simulations, applying a moving block bootstrap algorithm with a block length of 1. We were searching for two break points in the time intervals between 16 and 13 kyr BP. The two subintervals (one for each break point) were ranging from the outer boundary next to the break point of interest to the other break point. Subintervals were finally identified after at least two iterative applications to (in kyr BP): break point 1 [15.74, 14.45] and break point 2 [14.67, 13.16]. Breakfit identified the start in the Δ14C drop at 14.66±0.07 kyr BP followed by its decline by 54±8‰ within 207±95 years. Because of the very distinct dynamics of atmospheric Δ14C including a rebound after its minimum (that is, after the carbon release to the atmosphere stopped), we also analysed the data more subjectively with a non-linear approach. Here we only calculated the mean time and mean Δ14C right at the start of the carbon cycle changes around 14.6 kyr BP (two data points) and at its minimum (eight data points) assuming that Δ14C followed a non-linear pathway between both and included a rebound thereafter. The Δ14C data then starts to decline at 14.59±0.04 kyr BP and stop after 258±53 years with a maximum drop of 58±14‰ followed by a rebound of atmospheric Δ14C. This non-linear dynamic is seen in the Tahiti data but also in our carbon cycle simulations (Figs 2 and 4a). Combining the linear and non-linear approach brings high confidence that the Δ14C drop started at around 14.6 kyr BP. All uncertainties are given as 1σ.

Possible Δ14C signature of permafrost carbon

The maximum possible Δ(Δ14C) of carbon released from permafrost thawing is a function of age and of atmospheric Δ14C during time of production. From the Δ14C signature (IntCal13) (ref. 9) of the precursor material (atmospheric CO2), which varies before the B/A roughly between 250 and 550‰ (Fig. 6a), we first subtract the mean Δ14C value of terrestrial carbon at the LGM in the model (−50‰) before a further reduction in Δ14C signature is realised by the radioactive decay of 14C (half-life time of 5,730 years).

Carbon cycle model

We use the carbon cycle box model BICYCLE in transient mode to simulate changes in atmospheric CO2 and Δ14C. The model setup is identical to an earlier study, which already proposed the magnitude of the CO2 overshoot during the B/A6.

We simulate the release of 125 Pg of carbon into the atmosphere with a constant rate that varies inversely with the time length of the event between 0.42 Pg C per year (300 years) and 2.5 Pg C per year (50 years) and configured the AMOC in either its strong or its weak mode. Both AMOC configurations differ in the strength of the overturning cell in the Atlantic with 16 Sv deep water production in the North Atlantic in the strong mode and 2 Sv in the weak mode. We repeated our previous comparison6 of simulated atmospheric δ13CO2 to ice core data from the EDC because new δ13CO2 data were published in the mean time1. For this model-data comparison of δ13CO2, we distinguished terrestrial and marine sources of the released carbon by assuming a δ13C signature of −22.5 and −8.5‰, respectively (Fig. 3b). More details on these assumptions are found in our previous article6. Δ(Δ14C) of the simulated carbon release is depleted with respect to the atmosphere between −50 and −1,250‰. Initial conditions of 14C production rates influence simulated Δ14C over several ten thousand years32. All simulations therefore start at 60 kyr BP. In our standard case, 14C production rates are assumed to be constant and 15% higher than present day, leading to atmospheric Δ14C of +250‰ at 14.6 kyr BP in agreement with IntCal13 (ref. 9). Long-term trends in 14C production rate as suggested by the geomagnetic field data32 only slightly impact our simulations (Supplementary Fig. 4).

For model evaluation, BICYCLE is (a) compared in its oceanic carbon uptake dynamic resulting in a model-specific airborne fraction with other models, (b) used to simulate the Suess effect (years 1820–1950 AD), (c) the bomb 14C peak (years 1950–2000 AD) and (d) applied on CO2 release experiments for preindustrial background conditions. The model is compared with the results from another carbon cycle box model66 (Suess effect and for preindustrial conditions) and with output from the GENIE model67, an Earth system model of intermediate complexity (preindustrial conditions). All details on this model evaluation are found in the Supplementary Note 2 including Supplementary Figs 6–8.

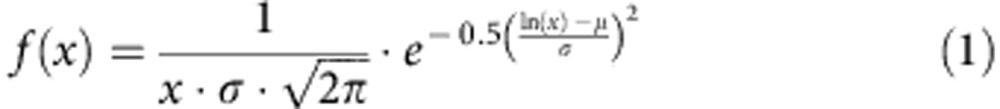

Filtering true atmospheric CO2 into signals recorded in EDC

The smoothing effect of the gas enclosure process in ice cores that transforms a potential true atmospheric CO2 into a time series comparable to EDC ice core data is performed with a log-normal probability density function with an assumed mean value or width E of 400±80 years (mean ±1σ)6 (Supplementary Fig. 2c):

|

with x (in years) as the time elapsed since the last exchange with the atmosphere. From the two free parameters, μ and σ of the equation, we chose for simplicity σ=1, which leads to E=eμ−0.5. The application of such a filter function for the transformation of true atmospheric signals into those that might be recorded in ice cores during rapid climate change was compared with results from firn densification models and extensively validated with CH4 data from both hemisphere6.

Author contributions

All authors designed research; P.K. performed carbon cycle simulations with BICYCLE; E.B. performed carbon cycle simulations with other box models; G.K. performed climate simulations; P.K. drafted the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Köhler, P. et al. Permafrost thawing as a possible source of abrupt carbon release at the onset of the Bølling/Allerød. Nat. Commun. 5:5520 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6520 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Notes 1-3 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Fischer for some insights on CH4 in ice cores and T. Opel for details on permafrost. R. Muscheler calculated GISP2 10Be fluxes and provided all GISP2 10Be data on the GICC05 age scale. A. Ridgwell provided helpful comments and GENIE model results used for carbon cycle model evaluation. K. Saito provided PMIP3 result on LGM permafrost distribution. M. Mudelsee helped with the application of the Breakfit software, V. Helm transformed IDL data into netCDF. G.K. acknowledges helpful discussions with G. Lohmann and S. Barker. G.K. is funded by REKLIM. E.B. is supported by the European Community (Project Past for Future) and by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Project EQUIPEX ASTER-CEREGE).

References

- Schmitt J. et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science 336, 711–714 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner L. C., Fallon S., Waelbroeck C., Michel E. & Barker S. Ventilation of the deep Southern Ocean and deglacial CO2 Rise. Science 328, 1147–1151 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrenin F. et al. Synchronous change in atmospheric CO2 and Antarctic temperature during the last deglacial warming. Science 339, 1060–1063 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veres D. et al. The Antarctic ice core chronology (AICC2012): an optimized multi-parameter and multi-site dating approach for the last 120 thousand years. Clim. Past 9, 1733–1748 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner M. et al. High-resolution interpolar difference of atmospheric methane around the Last Glacial Maximum. Biogeosciences 9, 3961–3977 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Köhler P., Knorr G., Buiron D., Lourantou A. & Chappellaz J. Abrupt rise in atmospheric CO2 at the onset of the Bølling/Allerød: in-situ ice core data versus true atmospheric signals. Clim. Past 7, 473–486 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Durand N. et al. Comparison of 14C and U-Th ages in corals from IODP #310 cores offshore Tahiti. Radiocarbon 55, 1947–1974 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. et al. 800,000 Years of abrupt climate variability. Science 334, 347–351 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer P. J. et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0-50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 55, 1869–1887 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D. L. et al. Towards radiocarbon calibration beyond 28 ka using speleothems from the Bahamas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 289, 1–10 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Southon J., Noronha A. L., Cheng H., Edwards R. L. & Wang Y. A high-resolution record of atmospheric 14C based on Hulu Cave speleothem H82. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 33, 32–41 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Hughen K., Southon J., Lehman S., Bertrand C. & Turnbull J. Marine-derived 14C calibration and activity record for the past 50,000 years updated from the Cariaco Basin. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 25, 3216–3227 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Noronha A. L. et al. Assessing influences on speleothem dead carbon variability over the Holocene: implications for speleothem-based radiocarbon calibration. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 394, 20–29 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bronk Ramsey C. et al. A complete terrestrial radiocarbon record for 11.2 to 52.8 kyr B.P. Science 338, 370–374 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard E. Correction of accelerator mass spectrometry 14C ages measured in planktonic foraminifera: paleoceanographic implications. Paleoceanography 3, 635–645 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Knorr G., Lohmann G. & Zhang X. Dependence of abrupt Atlantic meridional ocean circulation changes on climate background states. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3698–3704 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Butzin M., Prange M. & Lohmann G. Readjustment of glacial radiocarbon chronologies by self-consistent three-dimensional ocean circulation modeling. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317-318, 177–184 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Singarayer J. S. et al. An oceanic origin for the increase of atmospheric radiocarbon during the Younger Dryas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L14707 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Capron E. et al. Glacial-interglacial dynamics of Antarctic firn columns: comparison between simulations and ice core air δ15N measurements. Clim. Past 9, 983–999 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Freitag J., Kipfstuhl J., Laepple T. & Wilhelms F. Impurity-controlled densification: a new model for stratified polar firn. J. Glaciol. 59, 1163–1169 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J. L. et al. An ice core record of near-synchronous global climate changes at the Bølling transition. Nat. Geosci. 7, 459–463 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Monnin E. et al. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last glacial termination. Science 291, 112–114 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S. O. et al. A new Greenland ice core chronology for the last glacial termination. J. Geophys. Res. 111, D06102 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen J. P. et al. High-resolution Greenland ice core data show abrupt climate change happens in few years. Science 321, 680–684 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neftel A., Oeschger H., Staffelbach T. & Stauffer B. CO2 record in the Byrd ice core 50,000-5,000 years BP. Nature 331, 609–611 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. J., Fischer H., Wahlen M., Mastroianni D. & Deck B. Dual modes of the carbon cycle since the Last Glacial Maximum. Nature 400, 248–250 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J. et al. A record of atmospheric CO2 during the last 40,000 years from the Siple Dome, Antarctica ice core. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D13305 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Pedro J. B., Rasmussen S. O. & van Ommen T. D. Tightened constraints on the time-lag between Antarctic temperature and CO2 during the last deglaciation. Clim. Past 8, 1213–1221 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Marchitto T. M., Lehman S. J., Oritz J. D., Flückiger J. & van Geen A. Marine radiocarbon evidence for the mechanism of deglacial atmospheric CO2 rise. Science 316, 1456–1459 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott L., Southon J., Timmermann A. & Koutavas A. Radiocarbon age anomaly at intermediate water depth in the Pacific Ocean during the last deglaciation. Paleoceanography 24, PA2223 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps P. et al. Ice-sheet collapse and sea-level rise at the Bolling warming 14,600 years ago. Nature 483, 559–564 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler P., Muscheler R. & Fischer H. A model-based interpretation of low frequency changes in the carbon cycle during the last 120 000 years and its implications for the reconstruction of atmospheric Δ14C. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, Q11N06 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Kindler P. et al. Temperature reconstruction from 10 to 120 kyr b2k from the NGRIP ice core. Clim. Past 10, 887–902 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Gorham E., Lehman C., Dyke A., Clymo D. & Janssens J. Long-term carbon sequestration in North American peatlands. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 58, 77–82 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Sowers T. Late Quaternary atmospheric CH4 isotope record suggests marine clathrates are stable. Science 311, 838–840 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H. et al. Changing boreal methane sources and constant biomass burning during the last termination. Nature 452, 864–867 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller L. et al. Independent variations of CH4 emissions and isotopic composition over the past 160,000 years. Nat. Geosci. 6, 885–890 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Schaphoff S. et al. Contribution of permafrost soils to the global carbon budget. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 014026 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. et al. Transient simulation of last deglaciation with a new mechanism for Bølling-Allerød warming. Science 325, 310–314 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciais P. et al. Large inert carbon pool in the terrestrial biosphere during the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Geosci. 5, 74–79 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Saito K. et al. LGM permafrost distribution: how well can the latest PMIP multi-model ensembles reconstruct? Clim. Past 9, 1697–1714 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe J. et al. The Last Permafrost Maximum (LPM) map of the Northern Hemisphere: permafrost extent and mean annual air temperatures, 25-17 ka BP. Boreas 43, 652–666 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Koven C. D. et al. Permafrost carbon-climate feedbacks accelerate global warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14769–14774 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuur E. et al. Expert assessment of vulnerability of permafrost carbon to climate change. Clim. Change 119, 359–374 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko V. V. et al. 14CH4 measurements in Greenland ice: investigating last glacial termination CH4 sources. Science 324, 506–508 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostek F. & Bard E. Hydrological changes in eastern Europe during the last 40,000 years inferred from biomarkers in Black Sea sediments. Quaternary Res. 80, 502–509 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ridgwell A., Maslin M. & Kaplan J. O. Flooding of the continental shelves as a contributor to deglacial CH4 rise. J. Quaternary Sci. 27, 800–806 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. E. et al. Millennial-scale variability in Antarctic ice-sheet discharge during the last deglaciation. Nature 510, 134–138 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark P. U., Mitrovica J. X., Milne G. A. & Tamisiea M. E. Sea-level fingerprinting as a direct test for the source of global meltwater pulse IA. Science 295, 2438–2441 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W. H. & Sandwell D. T. Global sea floor topography from satellite altimetry and ship depth soundings. Science 277, 1956–1962 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J. et al. The deep permafrost carbon pool of the Yedoma region in Siberia and Alaska. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 6165–6170 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonk J. E. et al. Activation of old carbon by erosion of coastal and subsea permafrost in Arctic Siberia. Nature 489, 137–140 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X. et al. Differential mobilization of terrestrial carbon pools in Eurasian Arctic river basins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14168–14173 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAIS Divide Project Members. Onset of deglacial warming in West Antarctica driven by local orbital forcing. Nature 500, 440–444 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J. & Brook E. J. Atmospheric CO2 and climate on millennial time scales during the last glacial period. Science 322, 83–85 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Lohmann G., Knorr G. & Xu X. Different ocean states and transient characteristic in Last Glacial Maximum simulations and implications for deglaciation. Clim. Past 9, 2319–2333 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. & Knorr G. Antarctic climate signature in the Greenland ice core record. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17278–17282 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourantou A., Chappellaz J., Barnola J.-M., Masson-Delmotte V. & Raynaud D. Changes in atmospheric CO2 and its carbon isotopic ratio during the penultimate deglaciation. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 29, 1983–1992 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R., Schmitt J., Köhler P., Joos F. & Fischer H. A reconstrution of atmospheric carbon dioxide and its stable carbon isotopic composition from the penultimate glacial maximum to the last glacial inception. Clim. Past 9, 2507–2523 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Delmotte V. et al. Abrupt change of Antarctic moisture origin at the end of Termination II. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 107, 12091–12094 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landais A. et al. Two-phase change in CO2, Antarctic temperature and global climate during Termination II. Nat. Geosci. 6, 1062–1065 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Stenni B. et al. Expression of the bipolar see-saw in Antarctic climate records during the last deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 4, 46–49 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Buiron D. et al. Regional imprints of millennial variability during the MIS 3 period around Antarctica. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 48, 99–112 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Khvorostovsky D. V. et al. Vulnerability of permafrost carbon to global warming. Part II: sensitivity of permafrost carbon stock to global warming. Tellus B 60, 265–275 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Mudelsee M. Break function regression. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 174, 49–63 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Bard E., Raisbeck G. M., Yiou F. & Jouzel J. Solar modulation of cosmogenic nuclide production over the last millennium: comparison between 14C and 10Be records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 150, 453–462 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Cao L. et al. The role of ocean transport in the uptake of anthropogenic CO2. Biogeosciences 6, 375–390 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Lourantou A. et al. Constraint of the CO2 rise by new atmospheric carbon isotopic measurements during the last deglaciation. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 24, GB2015 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- EPICA-community-members. One-to-one coupling of glacial climate variability in Greenland and Antarctica. Nature 444, 195–198 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGRIP Members. High-resolution record of Northern Hemisphere climate extending into the last interglacial period. Nature 431, 147–151 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Notes 1-3 and Supplementary References