Abstract

Aims and objectives

To understand how patients experience compassion within nursing care and explore their perceptions of developing compassionate nurses.

Background

Compassion is a fundamental part of nursing care. Individually, nurses have a duty of care to show compassion; an absence can lead to patients feeling devalued and lacking in emotional support. Despite recent media attention, primary research around patients' experiences and perceptions of compassion in practice and its development in nursing care remains in short supply.

Design

A qualitative exploratory descriptive approach.

Methods

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 10 patients in a large teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic networks were used in analysis.

Results

Three overarching themes emerged from the data: (1) what is compassion: knowing me and giving me your time, (2) understanding the impact of compassion: how it feels in my shoes and (3) being more compassionate: communication and the essence of nursing.

Conclusion

Compassion from nursing staff is broadly aligned with actions of care, which can often take time. However, for some, this element of time needs only be fleeting to establish a compassionate connection. Despite recent calls for the increased focus compassion at all levels in nurse education and training, patient opinion was divided on whether it can be taught or remains a moral virtue. Gaining understanding of the impact of uncompassionate actions presents an opportunity to change both individual and cultural behaviours.

Relevance to clinical practice

It comes as a timely reminder that the smallest of nursing actions can convey compassion. Introducing vignettes of real-life situations from the lens of the patient to engage practitioners in collaborative learning in the context of compassionate nursing could offer opportunities for valuable and legitimate professional development.

Keywords: compassion, empathy, interviews, nursing care, patients' experience, patients' perceptions

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

This research contributes to the body of knowledge that compassion is fundamental to nursing care and provides some empirical evidence on how patients perceive compassion as conveyed through the basic nursing care they receive.

The effects of the lack of compassion in care should not to be undervalued.

This research reaffirms that some patients believe their experiences can offer legitimate and valuable learning for nurses in relation to compassion.

For some, compassionate actions may only need to be fleeting, rather than the product of relationships established between nurses and the patients they care for.

Introduction

Compassion unites people in difficult times and is a foundation to building human relationships which can promote both physical and mental health (Gilbert 2010). In the United Kingdom (UK), the importance of compassion in care is highlighted in a number of recent healthcare documents arguing that nurses should provide compassionate care to patients (Health Service Ombudsman 2011, Department of Health 2012, Francis 2013). However, there is increasing concern worldwide that despite the growing capabilities and sophistication of healthcare systems, there is a failure at a fundamental level with care and compassion (Youngson 2008).

There is a need to address and evaluate how compassion can become an integral part of nursing care within teams (Firth-Cozens & Cornwell 2009), and there should be an increased focus on a culture of compassion at all levels in nurse education, training and recruitment (Francis 2013). Designing and implementing education strategies to meet the challenge of ensuring that nursing care is delivered with compassion is a priority. However, practice development and implementing the evidence base can be a difficult task, particularly when there is a lack of such evidence and/or increasing recognition being given to different sources of evidence (Gerrish & Clayton 2004).

Questions remain as to how compassion in nursing care is shown (Van Der Cingel 2009), particularly from the lens of the patients. This paper is based on research conducted to explore patients' experiences of compassion within the nursing care they receive and understand their views on how nursing can address perceived lack of compassion within care. The results of this study were intended to inform the design of compassion-related toolkit of resources to inform nursing practice in a large National Health Service (NHS) University teaching hospital within the United Kingdom.

Background

Compassion is a complex phenomenon and is difficult to define (Van Der Cingel 2009, 2011). There is currently little evidence of a complete definition, and many working definitions cited in the literature are steeped in the Aristotelian virtue of suffering as illustrated by Chochinov (2007 p. 186) who describes compassion as follows:

…a deep awareness of the suffering of another coupled with the wish to relieve it.

Whilst useful, this definition alone does not give the whole use of the term within nursing, where words such as empathy, sympathy and caring are often used interchangeably with compassion (Snow 1991, Von Dietze & Orb 2000, Schantz 2007). Whilst nurses are certainly not strangers to witnessing suffering, compassionate care is not simply about relieving suffering, but about entering into a patient's experience and enabling them to retain their independence and dignity (Von Dietze & Orb 2000).

This aspect of compassion has been described as a moral virtue, something that nurses are just expected to do. It also represents an ethical dimension to care (Von Dietze & Orb 2000, Maben et al. 2009) and has been described as the essence of caring, therefore the essence of nursing (Chambers & Ryder 2009). Perhaps the most accessible definition comes from Dewar (2011) in her address at the 2010 Royal College of Nursing (RCN) International Conference:

…the way in which we relate to human beings. It can be nurtured and supported. It involves noticing another person's vulnerability, experiencing an emotional reaction to this and acting in some way with them, in a way that is meaningful for people. It is defined by the people who give and receive it, and therefore interpersonal processes that capture what it means to people are an important element of its promotion.

This definition derives from work conducted between NHS Lothian and Napier University (Dewar 2011) and seems to capture the essence of compassion as experienced both by individual patients and nurses in partnership. The definition not only acknowledges the complex nature of compassion but also reminds us of its subjectivity in the context of health care from both a nursing and patient perspective.

In the United Kingdom, this human dimension of caring has been given increasing prominence in health care. Lord Darzi (2008) in his next stage review of the NHS called for high-quality care for all patients to be treated with dignity, compassion and respect, the Prime Minister's Commission (2010) made compassionate care central to its report, and more recently, ‘compassion in practice’ has been published (Department of Health 2012) by the chief nursing officer in England and Wales with compassion being central to her vision for nursing.

In direct contrast, however, the Patients Association (2009, 2011, 2012) reported patient experiences deficient in basic nursing care, and the ‘Care and Compassion Report’ from the Health Service Ombudsman presented the reality of lack of compassion within health care (Health Service Ombudsman 2011). More recently, all of these issues were highlighted once again in the high-profile Francis report, which cited compassionate care as an overarching theme that was lacking (Francis 2013). These accounts present a picture of a NHS that is failing to respond with compassion to the needs of patients.

To improve nursing practice, it is important to identify what compassion is from the patients' perspective. Knowing what patients perceive compassion to be would greatly assist in the provision of compassionate care in practice. Recent work has identified the need for descriptive accounts derived from the perspective of the patient and called for further empirical research to articulate compassion and compassionate care (Burnell 2009). Following a study of patients' perceptions of the qualities of a compassionate nurse, it was recognised that additional research will lead to better understanding of what it means to be a compassionate nurse (Kret 2011).

Aim

The aim of this study was to understand how patients experience compassion within nursing care and explore their perceptions of developing compassionate nurses.

Methods and design

For the purpose of this study, a qualitative exploratory descriptive approach using semi-structured face-to-face interviews was chosen to most appropriately explicate the patients' experiences and perceptions. Qualitative research is an activity that situates and locates the observer in the world (Denzin & Lincoln 2005). An interpretivist, naturalistic approach was used to study participants within a hospital setting in an attempt to make sense and interpret the phenomena of interest as it occurred.

There is currently little research that exists of the patients' experiences of compassion within the nursing care they receive or qualitative inquiry that seeks to explore and understand the patients' perceptions of developing compassionate nurses within practice. Understanding key issues within nursing practice from the perspectives of patients is essential to ensure that initiatives are informed by the people who will benefit from them.

Study setting and sample

A purposive sample of 10 hospital inpatients were recruited from within six acute medical wards specialising in respiratory medicine (n = 4), stroke (n = 2), endocrinology (n = 3) and health care of older people (n = 1) of a large NHS University teaching hospital in the East Midlands, United Kingdom. Participants were aged between 18–91 and included both female (n = 5) and male (n = 5) patients. Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: adult inpatients with capacity to consent (as determined by the Department of Health 2005), who had been an inpatient for longer than 24 hours, felt well enough to participate and were within approximately 24 hours of discharge. Those who lacked capacity to consent or had been previously cared for by the primary author who is a nurse were excluded. All participants recruited were inpatients and had experienced between 4–10 days of nursing care with one exception, which was an eight-week stay.

Data collection and analysis

Participants were recruited over three months between April–June 2012. Nursing staff were fully informed of the study and, with the permission of the clinical lead, agreed to identify participants who matched the inclusion criteria. Once potential participants had been identified, they were approached by the nursing staff to determine their willingness to speak with the researcher about the study, to prevent or dispel any coercion. With permission, the study was then explained, and an information sheet given to potential participants. They were then given 24 hours to consider the information before being asked for written informed consent.

Following consent, semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants using an interview schedule with prompts as a guide (see Table1). All interviews were conducted by the first author in a quiet room on the ward, in which the participant was receiving care. With permission, all interviews were digitally recorded and lasted between 35–60 minutes. The interviews did not delay discharge from hospital, and all participants were discharged shortly after the interviews were complete. There was no further contact with participants following this.

Table 1.

Interview schedule

| I am interested in the specific aspects of compassionate nursing care you have received during your stay in hospital this time and how you feel it has been |

| 1. Please can I start by asking you a general question about what you feel compassionate nursing care means to you? |

| 2. Please would you describe a situation, if there has been one, when you feel you have experienced compassionate care during your stay in hospital this time? |

| What was happening at the time? |

| What exactly was said by the nurse? |

| What exactly was the nurse doing, e.g. standing, walking away? |

| What else was happening on the ward? |

| Please will you tell me how that felt? |

| 3. Please would you describe a situation, if there has been one, when you felt compassionate nursing care was missing during your stay? |

| What was happening at the time? |

| What exactly was said by the nurse? |

| What exactly was the nurse doing, e.g. standing, walking away |

| What else was happening on the ward? |

| Please will you tell me how that felt? |

| 4. In what ways do you think compassionate nursing care could be improved? |

| 5. What can you tell me, if anything, about what you think prevents nurses from delivering compassionate care? |

| 6. In what ways, if any, do you think it makes a difference if the nursing care you receive is compassionate? |

| How does it make you feel? |

| Why do you think it makes a difference? |

| 7. What can you tell me, if anything, that you think would help nurses to be more compassionate in the care they give? What do you think this would make an improvement? |

| How do you think this may be achieved? |

| 8. What else, if anything, you would like to tell me or comment on with regard to compassionate nursing care? |

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data using the thematic networks analytic tool as described by Attride-Stirling (2001). Initially, data reduction was achieved by coding text into manageable and meaningful segments with the use of a coding framework. This framework was derived from the salient issues arising from the text, in conjunction with the pre-established criteria on which the interview schedule was built.

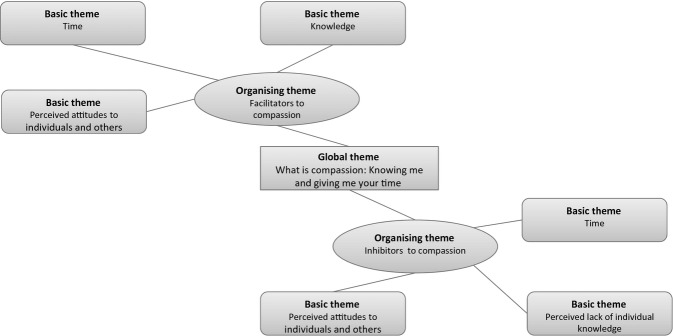

Basic themes then emerged and were coded as such. During analysis, it became apparent that the context of the narrative data that formed the basic themes could be described as both facilitators and inhibitors to compassion, so these naturally progressed into the organising themes. Three global themes then emerged through a process of reorganisation and were established through a process of consensus alongside the other researchers. Figure1 is an example of a thematic network.

Figure 1.

Thematic network for global theme: ‘what is compassion: knowing me giving me your time’.

Ethical consideration

Prior to the study, ethical approval was sought and gained from the national research ethics service and research and innovation department of the hospital used in the study. All data collected were anonymised to maintain participant confidentiality and stored securely in a locked cupboard in accordance with the data protection act 1998. Each participant and ward were assigned a study identity code number to be used on forms and the electronic database.

Full written informed consent was gained prior to interviews commencing. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and emphasis was placed on the participants' right to withdrawal at any time without it affecting their care. The information sheet clearly explained that in the event of poor practice being exposed, it would be reported in accordance with hospital policy to prevent any further occurrences.

During the interviews, three participants became distressed whilst discussing their care. In two of these instances, the interview was suspended and then restarted after a short period of time with the patient's permission. However, one interview was suspended after consent was withdrawn, and the interview was not transcribed. In all instances and with the participants' permission, ward staff were then informed of the distress should further assistance have been required.

The recording of the patient interview data was destroyed as soon as the transcripts had been checked in keeping with the ethics committee approval. There were no conflict of interests identified in this case, and no legal issues as a result of exposure of poor practice were identified.

Establishing trustworthiness

Improving the probability that interpretations can be found credible is essential and can be done with the use of reflexivity and peer checking (Lincoln & Guba 1985, Graneheim & Lundman 2004). Peer checking was used in the data analysis phase of this project; transcripts were given to two other researchers alongside an experienced qualitative researcher in an attempt to mediate personal bias. Despite criticism that this could be too superficial (Giacomini & Cook 2000), consensus was reached on the emerging themes.

The process of reflexivity is referred to as the hallmark of excellence by Sandelowski and Barroso (2002) and requires that researchers have the ability and willingness to acknowledge and to take account of the ways in which they themselves influence the findings. Leslie and McAllister (2002) recognise the unique contribution nurses can make to the research process, particularly with regard to difficult situations, and recognising these skills has been crucial to ensuring credibility of the findings. At times throughout this process, patients became upset and indeed one patient became too upset to continue, and the interview was abandoned. The researcher's expertise and influence as a nurse during this time was crucial to ensuring that the participant had time to talk through their visible distress.

According to Polit and Beck (2010), transferability is a collaborative enterprise between the research and reader. By providing ‘thick’ descriptions of the setting, study participants and observed transactions and processes (Lincoln & Guba 1985), it is hoped to guide the reader towards extrapolating and making inferences about the findings in other areas. This process has been assisted by the use of a reflexive research diary which has proven useful in relaying not only the rationale underpinning the research, but also the actual course of the research process as it arose in the study.

Results and discussion

The findings and discussion of this work are presented together to ensure that interpretation of the findings can be presented alongside description to provide insight into the experience of the participants (Chamberlain 2000). Three overarching themes emerged from the data: (1) what is compassion: knowing me and giving me your time; (2) understanding the impact of compassion: how it feels in my shoes; and (3) being more compassionate: communication and the essence of nursing. Verbatim quotes are used in the discussion below to highlight the views of the patients.

What is compassion: knowing me and giving me your time

This theme represents what a compassionate nurse is from the perspectives of the patients and how they perceive it within care. First and foremost, care and caring was mentioned throughout the transcripts most often in relation to compassion. The connection between compassion and caring was so strong that many participants did not delineate between the two, often substituting ‘compassion’ for ‘care’ and ‘caring’ throughout the interviews:

Compassion, it means a caring attitude to people as people and not as things.

(Participant 5, ward D: L 4)

To be compassionate within the nursing care I would say is to not just treat a person as a body really and to be concerned and interested in how that body is functioning for that particular person and the person's feelings about their size or their inability to do something that they can normally do for themselves… Like I needed to use a bed pan for the very first time and the compassion there was the fact that he knew he was a man, he knew I was uncovered, he knew I was embarrassed and he tried to put himself in my situation.

(Participant 1, ward B: L 6-8)

Compassion was described within this study as nurses caring for patients as individual human beings and the presence of their touch within one to one interactions. It was seen as providing encouragement in adversity and making time to be with individual patients. It was also seen in nurses' attitudes. Most importantly, it was a unique experience personalised for individuals in relation to their own needs, and what was seen as an important aspect of compassion for one patient may well have been overlooked or not recognised as such by another.

Entering into the patient experience, delivering care and enabling patients to maintain their independence has been described as a moral virtue, bringing an ethical dimension to care and something that nurses are just expected to do (Von Dietze & Orb 2000, Maben et al. 2009). Theorist Jean Watson (1999) articulates these ethical human care transactions as ‘caring occasions/caring moments’ which form a fundamental component of her caring theory. These findings also bare resemblance to what Watson terms ‘unique phenomenal fields’ which corresponds to a person's frame of reference and is wholly dependent on individual nurse and patient experiences (Watson 1999).

The importance of this relational aspect of compassion to the participants in this study cannot be overlooked when planning and implementing care. According to Gordon (2006), compassion is a process that can be nurtured through attention to patient-centred assessment and planning of care. Patient centeredness is no stranger to nursing discourse, however, adopting this element to care and compassion is challenging in today's healthcare arena, especially when treating massively increased numbers of patients (Goodrich 2012).

Giving time to care or being seen as not making time was instrumental in compassion. Patients expected nurses to have time for patients and listen to them. Universal acknowledgement of the busy ward environment and meant time became a precious commodity in care and compassion. Those nurses that were seen as making time despite pressures were deemed compassionate, whilst a patient having to wait due to these time pressures observed care as less compassionate:

And they were most uncompassionate, there were people, elderly people who couldn't walk actually and really needed help and really needed the toilet or whatever and the nurses were just saying sorry, there are only three of us you will have to wait your turn.

(Participant 9, ward A: L 42-46)

It has been recognised that compassion in care takes time and commitment from practitioners (Hayter 2010) and has often been cited as a reason for lack of compassion. However, according to some participants, this element of time needed only to be fleeting to establish a compassionate connection and need not be an arduous task:

Well, they look or touch and feel and put their hands on your shoulders. well… you know, people they respond to that…it makes you feel like a human being. I know they are busy but the small things show they care.

(Participant 5, ward D: L86-87)

This seems to suggest that patients recognise that nurses are busy and they are happy to adapt to smaller gestures of compassion that may not involve time for relationships to be established. Either way, Watson's perceived ‘caring moments’ whether through establishing relationships or fleeting in nature are important to the patients in this study as signs of compassionate care. Thus, it would seem only correct that compassion retains it right as a central tenet of nursing practice.

Participants also felt that patients' behaviour towards nurses was often directly related to how compassionate the nurses were, and even in adverse circumstances, nurses often remained compassionate:

I have always found they have always been all right [the nurses] in hospital actually, I think a lot if it is the way the patients are, some of them aren't very good are they … if they have a nasty patient, then you have got a problem haven't you?

(Participant 4, ward A: L28-30)

There was an elderly gentleman tried to get out of bed on his own, he had been told not to so it was nobody else's fault but his own…but he would try to get out of bed, but he fell and that don't mean [sic] that he deserved what he got, but as I say it was his own fault. They dashed to his aid, looked after his injuries, I mean they could have just grabbed hold of him and said he shouldn't have got out

(Participant 9, ward A: L14-27)

This seems to suggest that a compassion caring action is not always seen as a two-way interaction by some patients. It may also confirm that time is not always needed to ensure that a compassion relationship is created. Many nurses can indeed maintain compassionate action within the care they give and often in adversity.

Understanding the impact of compassion: how would I feel in their shoes?

‘How would I feel in their shoes’ implies being empathetic. Noddings (2003) analysed caring from a philosophical standpoint and noted that often a person caring for another is motivated to resolve the discomfort of another by engrossing themselves in their plight. This viewpoint of caring seems to resonate with the earlier presented definitions of compassion in which a deep awareness of others suffering and a wish to relieve suffering are common. The impact of individual nurses empathetic behaviour was heartfelt by the patients receiving care as well as observing the care of others. Although quantifying patient outcomes within this context is difficult, the positive impact on overall well-being was clear:

I feel very isolated being in a side room and I am quite a social person so you know her coming in here to talk to me about it and be with me for a while just made me feel so much better.

(Participant 7, ward C: L 46-48)

Interestingly and overwhelmingly patients wanted the nurses to understand how it also feels to be them to be nursed in an uncompassionate way:

How would I feel in their shoes? I mean really in their shoes how would I feel.

(Participant 1, ward B: L 239)

This was particularly pertinent when nursing behaviour was seen as uncompassionate and was seen by participants as a way for nurses to understand how to be more compassionate and would instigate a change in their actions. In direct contrast to this, however, Dewar (2011) found success through appreciative inquiry by identifying and promoting positive actions to change behaviour in relation to compassionate care and liberating nurses to be more compassionate. These principles contend that the more positive the action to which a system is subject to, the more positive and long lasting the desired change will be (Nicholson & Barnes 2013).

Being more compassionate: the essence of nursing and communication

This theme relates to what could help nurses be more compassionate which was an area of contention amongst participants. Some felt that this compassionate element was integral to what nurses are, and it was this quality that had brought them into the profession and could not be changed:

Well you can try and teach them, but if they are not that way inclined you can't teach them.

(Participant 2, ward B: L 33-34)

Others felt that it was something that could be moulded and taught in much the same way as any other clinical skills:

I do not see why they cannot be taught [to be compassionate], I think so yes, I do not see why not.

(Participant 4, ward A: L 91-92)

I think so yes and then a period of training to remind the person, that the person in the bed or chair is hurting, they're frightened, they're bewildered and perhaps never experienced being in hospital before.

(Participant 1, ward B: L 147-150)

In the main, it was felt that individuals were responsible for their own behaviour; however, some felt it went deeper and was more fundamental in that it was learned behaviour as part of the ward culture:

Yes the whole ward seemed to be the same and I think it was because, erm the ward sisters were that way inclined.

(Participant 9, ward A: L 55- 56)

Despite individual nurses' usual manner, this was a very powerful influence in changing compassionate behaviour. Tackling nursing culture is fundamental in the improvement of attitudes because the most powerful figure in the group decides what practice is acceptable (Pope 2012), and a change in culture can often be enough to change compassionate behaviour. Johnston (2013), however, sees a more deep rooted problem that is endemic not just in the United Kingdom but further afield with a culture of just ‘getting the job done’, where values such as compassion are often not seen as important or simply ignored.

According to Youngson (2008), the experience of people and their families seeking care is often a reflection of how the organisation treats its own employees. The leaders of the very best healthcare organisations provide role models for the values and principles underlying people-centred care, achieving and maintaining excellent patients care requires strong role models, mentors and managers that lead by example (Francis 2013, Johnston 2013).

Finally, the divided opinion with regard to education was not the case when it came to communication. Universally, all participants felt that communication was a huge part of compassion. Communication includes verbal and nonverbal behaviour (Astbury 2008):

I won't emphasize enough for communication all the way down the line, between consultants, doctors, nurses, patients erm…if there has been a misunderstanding to put things right as quickly as we can and to get things back on course.

(Participant 8, ward C: L 229-232)

This acknowledges that human beings can be unpredictable and that misunderstandings can happen. Communication is central to effectiveness in team working and caring relationship based on compassion and benefits those being cared for and staff (Department of Health 2012). Key challenges to nursing staff in this context are to be compassionate and communicate with patients, even when difficult situations occur.

Limitations of the study

Although these findings should be understood only in the context of this specific study, it raises some interesting issues and debates and divided opinion with regard to developing compassion within nursing care from the patients' perspective. The small sample size, exclusion of very sick patients and those with dementia, is limiting to the transferability of the findings. It is also worth noting that all participants described their ethnicity as white British, and compassionate care may be perceived differently in a more culturally representative sample.

As previously mentioned, this study was conducted to inform the design of a toolkit to promote compassion amongst nurses at a large NHS acute trust. However, the acute nature of illness for the patients in the study is thus that compassion for them may be directly related to their level of vulnerability and dependency on nursing care. It should be acknowledged that patients who are less dependent on nurses for help with their basic care may give a different account. Further research expanding beyond acute patients exploring further the idea that compassion is conveyed in caring and may only need to be fleeting rather than dependant on relationships is required. Despite these limitations, it is hoped that the findings of this small study will also inform practice for others.

Implications for practice

Compassion in nursing care has been subjected to continuous discussion in the media and literature, and this study reaffirms that compassionate care is important in nursing. Nurses should provide care based on patients' individual needs. Knowing and involving patients and carers in their care is crucial to improve quality and for patients who are too ill or cannot articulate.

In addition, it comes as a timely reminder that the smallest of nursing actions can be viewed as a compassionate action by patients, something that can be forgotten in challenging times. The desire for nurses and patients to provide and receive compassionate care within a complex and outcome-focused healthcare environment is well recognised (Smith et al. 2010), however, in line with what some of the patients suggested more needs to be done. Nursing education should play major role in developing nurses' knowledge and skills that will help nurses to provide compassionate care (Matiti 2002, Department of Health 2012). This view is echoed by the World Health Organisation, who agrees that a good nurse has compassion, a quality that needs to be nurtured (Chan 2010).

This exploratory study found that patients felt that if nurses could witness their own uncompassionate behaviour this may encourage them to change. Compassionate care activities, such as hearing the stories of others, need to be considered as valuable and legitimate professional development competencies (Dewar et al. 2011). Introducing vignettes and role playing to engage practitioners in collaborative learning in the context of compassionate nursing care could offer such opportunities to staff. The realities of these changes in clinical practice with regard to compassion present the nursing profession with a difficult, but not insurmountable challenge.

Conclusion

This study shows that patients see compassion as closely aligned to the broader concept of conveying care within nursing practice. Whilst this study acknowledges that compassion takes time and commitment from practitioners, it also highlights the importance of fleeting elements of time that can establish a compassionate connection between nursing staff and patients. The demand on nurses' time has often been cited as a barrier to the forming of compassion within relationships. The evidence created here challenges this and reminds us as nurses that the smallest exchanges can convey a compassionate action.

Compassion in nursing is still seen as a moral virtue, something that nurses are just expected to do and has been described as the essence of caring, therefore the essence of nursing (Chambers & Ryder 2009). The idea that nurses can be taught how to be compassionate is a contentious issue, and despite dividing opinion amongst the participants of this study, it has been cited by the recent Francis (2013) report as a priority for nursing. This division of opinion bares specific relevance to the campaign launched by the chief nursing officer in the United Kingdom and suggests that the profession has some work to do convincing the public that individual nurses attitudes to care can be changed or improved. Moreover, patients here acknowledge that little will change where hospital and ward cultures dictate the behaviour of individual staff.

Universally, nursing staff gaining understanding of the impact of uncompassionate actions was felt by most to present an opportunity to change both individual and cultural behaviours. Whilst the nursing profession alone is working hard to promote the importance of compassion, it is unlikely to improve the total patient experience without a whole system change, which promotes the importance of a culture of compassion throughout the whole of healthcare organisations.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the patients who shared their thoughts and personal stories. This study was conducted as part of a fully funded NIHR scholarship to undertake an MA in research methods at the University of Nottingham. There are no conflict of interests.

Disclosure

The authors have confirmed that all authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship credit (www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html), as follows: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design of, or acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

The Journal of Clinical Nursing (JCN) is an international, peer reviewed journal that aims to promote a high standard of clinically related scholarship which supports the practice and discipline of nursing.

For further information and full author guidelines, please visit JCN on the Wiley Online Library website: http://wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jocn

Reasons to submit your paper to JCN:

High-impact forum: one of the world's most cited nursing journals, with an impact factor of 1·316 – ranked 21/101 (Nursing (Social Science)) and 25/103 Nursing (Science) in the 2012 Journal Citation Reports® (Thomson Reuters, 2012).

One of the most read nursing journals in the world: over 1·9 million full text accesses in 2011 and accessible in over 8000 libraries worldwide (including over 3500 in developing countries with free or low cost access).

Early View: fully citable online publication ahead of inclusion in an issue.

Fast and easy online submission: online submission at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jcnur.

Positive publishing experience: rapid double-blind peer review with constructive feedback.

Online Open: the option to make your article freely and openly accessible to non-subscribers upon publication in Wiley Online Library, as well as the option to deposit the article in your preferred archive.

References

- Astbury G. Communication. In: Mason T, editor; Mason-Whitehead EBA, editor. Key Concepts in Nursing. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 2001;1:385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Burnell L. Compassionate care: a concept analysis. Home Health Care Management & Practice. 2009;21:319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain K. Methodolatry and qualitative health research. Journal of Health Psychology. 2000;5:285–296. doi: 10.1177/135910530000500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers C. Ryder E. Compassion and Caring in Nursing. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. Reforming the Education of Physicians, Nurses, and Midwives [Online] World Health Organisation; 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2010/medical_ed_20101214/en/ (accessed 22 July 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. British Medical Journal. 2007;335:184–187. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39244.650926.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzi Lord. High Quality Care for All. London: Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK. Lincoln YS. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. 3rd edn. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Compassion in Practice – Nursing Midwifery and Care Staff Our Vision and Strategy. London: Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dewar B. Caring about Caring: An Appreciative Inquiry about Compassionate Relationship-Centred Care. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Napier University; 2011. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Dewar B, Pullin S. Tocheris R. Valuing compassion through definition and measurement. Nursing Management – UK. 2011;17:32–37. doi: 10.7748/nm2011.02.17.9.32.c8301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth-Cozens J. Cornwell J. The Point of Care, Enabling Compassionate Care in Acute Hospital Settings. London: The Kings Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationary Office; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish K. Clayton J. Promoting evidence-based practice: an organizational approach. Journal of Nursing Management. 2004;12:114–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini MK. Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life's Challenges. London: Constable; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich J. Supporting hospital staff to provide compassionate care: do Schwartz center rounds work in english hospitals? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2012;105:117–122. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. Beyond the bedside: what do nurses really do? Ohio Nurses Review. 2006;81:1. this article was originally published in the 02/02/06 online Advanced Practice Nursing eJournal published by www.medscape.com. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH. Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayter M. Editorial: researching sensitive issues. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:2079–2080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Service Ombudsman. Care and Compassion. London: The Stationary Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston B. Lessons from the final report of the Francis inquiry. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2013;19:159. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.4.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kret DD. The qualities of a compassionate nurse according to the perceptions of medical-surgical patients. Medsurg Nursing. 2011;20:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie H. McAllister M. The benefits of being a nurse in critical social research practice. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:700–712. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS. Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. London: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Maben J, Cornwell J. Sweeney K. In praise of compassion. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2009;15:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Matiti MR. Patient Dignity in Nursing: A Phenomenological Study. Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield; 2002. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Mental Capacity Act. London: The Stationary Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C. Barnes J. Appreciative Inquiry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings N. A Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF. Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope T. How person-centred care can improve nurses' attitudes to hospitalised older patients. Nursing Older People. 2012;24:32–36. doi: 10.7748/nop2012.02.24.1.32.c8901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schantz ML. Compassion: a concept analysis. Nursing Forum. 2007;42:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2007.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Dewar B, Pullin S. Tocher R. Relationship centred outcomes focused on compassionate care for older people within in-patient care settings. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2010;5:128–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow NE. Compassion. American Philosophical Quarterly. 1991;28:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- The Patients Association. Patients Not Numbers, People Not Statistics [Online] London: 2009. Available at: http://www.patients-association.com/Portals/0/Public/Files/Research%20Publications/Patients%20not%20numbers,%20people%20not%20statistics.pdf (accessed 2 July 2012) [Google Scholar]

- The Patients Association. We Have Been Listening, Have You Been Learning. London: The Patients Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Patients Association. Stories from Present, Lessons for the Future. London: The Patients Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The Prime Ministers Commission. Front Line Care: Report by the Prime Minister's Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England [Online] London: 2010. Available at: http://www.parliament.uk/deposits/depositedpapers/2010/DEP2010-0551.pdf (accessed 3 July 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Cingel M. Compassion and professional care: exploring the domain. Nursing Philosophy. 2009;10:124–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2009.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Cingel M. Compassion in care: a qualitative study of older people with a chronic disease and nurses. Nursing Ethics. 2011;18:672–685. doi: 10.1177/0969733011403556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Dietze E. Orb A. Compassionate care: a moral dimension of nursing. Nursing Inquiry. 2000;7:166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Postmodern Nursing and Beyond. Edinburgh: Chirchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Youngson R. Future Debates: Compassion in Healthcare: The Missing Dimension of Healthcare Reform? London: The NHS Confederation; 2008. [Google Scholar]