Abstract

Purpose

Management of renovascular hypertension remains controversial and problematic, in part due to failure of prospective trials to demonstrate added benefit to revascularization.

Recent Findings

Effective drug therapy often can achieve satisfactory blood pressure control, although concerns persist for the potential for progressive, delayed loss of kidney function beyond a stenotic lesion. Recent studies highlight benefits of renal artery stenting in subsets of patients including those with recurrent pulmonary edema and those intolerant to blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Occasional patients with recent deterioration in renal function recover sufficient GFR after stenting to avoid requirements for renal replacement therapy. Emerging paradigms from both clinical and experimental studies suggest that hypoxic injury within the kidney activates inflammatory injury pathways and microvascular rarification that may not recover after technically successful revascularization alone. Initial data suggest that additional measures to repair the kidney, including the use of cell-based therapy, may offer the potential to recover kidney function in advanced renovascular disease.

Summary

Specific patient groups benefit from renal revascularization. Nephrologists will increasingly be asked to manage complex renovascular patients different from those in randomized trials that require intensely individualized management.

Keywords: renal artery stenosis, stent, hypertension, transforming growth factor beta, inflammation, mesenchymal stem cells

Introduction

Although renovascular hypertension (RVH) remains the prototype of “secondary” hypertension, its management remains intensely controversial. For many years, initial evaluation of the hypertensive patient usually included some form of diagnostic testing to exclude underlying renal arterial stenosis based on the assumption such lesions should be corrected, usually with surgical revascularization. Most argue that development of effective and well-tolerated antihypertensive drug therapy, however, has rendered some of these strategies obsolete. Most RVH is now treated with antihypertensive drugs primarily. Some question whether renal revascularization is ever necessary or warranted. Medical management of hypertension and atherosclerotic disease thus has changed the landscape of renovascular hypertension. Since this topic was last reviewed in this journal (1) and elsewhere (2), no major new trial data have been presented. There have been several recent “systematic” and other reviews of the published data (3) (4,5).

Why, then, is the question still unresolved? Some argue that published trial data are flawed and subject to selection bias that partly accounts for major differences between positive observational reports and clinical experience as compared to these negative trials (6). Many clinicians continue to identify patients with progressive loss of kidney function and/or episodes of circulatory congestion (“flash pulmonary edema”) that improve substantially after restoring blood supply to the kidney (7,8) (9). Additional trials comparing medical therapy to revascularization continue to be proposed and undertaken (10), specifically addressing changes in individual kidney function as well as cardiovascular outcomes. One cannot completely overcome a “face validity” problem insofar as ignoring progressive vascular occlusion leading to loss of kidney function and volume control seems unreasonably nihilistic and self-defeating.

There is undoubtedly still an important role for renal revascularization for selected patients with renovascular hypertension. An important corollary to this point is that recent data underscore some fundamental changes in our understanding of renovascular disease. Experimental and clinical investigations of RVH demonstrate complex pathways of microvascular and inflammatory injury that may modify the role of renal revascularization and emphasize the need for adjunctive measures to repair kidney structures beyond vascular occlusion.

Medical therapy of hypertension with renovascular disease

Atherosclerotic renovascular disease (RVD) can be viewed as a “biomarker” for cardiovascular disease risk, and is highly prevalent in older patients with heart failure. Bourantas and colleagues characterized 366 patients in a community heart failure clinic in the U.K. as regards clinical parameters and the prevalence of RVD (11). One hundred twelve (31 %) had more than 50% occlusion, of which 41 (36.6%) were bilateral. Only a fraction of each group was considered “severe” (more than 70% lumen occlusion by MRA). Not surprisingly, those with RVD were older, more hypertensive, and had a greater prevalence of eGFR<60ml/min/1.73m2: 85% with RVD as compared to 39% without RVD, p<.001. Survival over five years of follow-up was markedly worse in the RVD group. By contrast, recent reports of fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) indicate younger ages, continued predominance of women (91%), relatively preserved GFR and better blood pressure response to renal angioplasty (rarely with the application of stents) (12).

Hence, recent authors and guideline recommendations emphasize the need for vigorous risk factor management for atherosclerotic disease, including blood pressure control, lipid management with statins, withholding tobacco use, and aspirin (13). Antihypertensive drug therapy now is effective in achieving goal blood pressure levels in most patients. Crossover rates from medical therapy to renal revascularization in recent trials appear to have fallen in recent years from 44% (in the Dutch Renal Artery Stenosis Intervention Cooperative (DRASTIC) trial) to 8–10% in the Angioplasty and Stenting for Renal Artery Lesions (ASTRAL) and Stent Placement in Patients With Atherosclerotic Renal Artery Stenosis and Impaired Renal Function (STAR) trials (3). Part of the increased effectiveness of medical therapy derives from wider application of blockade of the renin-angiotensin system for RVH. In a prospective, observational report from a registry in the United Kingdom, 621 subjects were analyzed over a ten-year period from 1999–2009 regarding the tolerability and utility of renin-angiotensin blockade with either angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy (14). Of these, RAAS blockade was tolerated without difficulty in 357 of 378 treated patients (92%), including 54/69 (78.3%) of those with bilateral high-grade (>60% occlusion) renal artery stenosis. When the characteristics and outcomes of 243 similarly followed patients treated without RAAS blockade were defined, similar blood pressures were achieved (150 / 79 mmHg (No ACE/ARB) vs 149/76 (ACE/ARB) mmHg), those treated with ACE/ ARBs were less likely to die (hazard ratio 0.61 (0.40 – 0.91, p=.02), despite having higher prevalence of diabetes (38% vs 28%, p=.0007). The U.S. Cardiovascular Outcomes for Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) trial mandated treatment with an ARB. Previous registry data indicate that RVD patients treated with agents blocking the renin-angiotensin system have a survival advantage during long term therapy (15). Preliminary reports from CORAL again indicate that the majority of patients tolerated this class of drug and achieved goal blood pressures, although outcome data from this trial have yet to be presented. Observational series report that estimated GFR is more likely to fall (−16.5 ml/min) in medically treated patients as compared to −4.5 ml/min in revascularized patients during more than 30 months of follow-up (16). A separate report argued that differences in GFR attributed to stenting disappeared after adjusting for baseline confounders (8), although medical therapy was somewhat less effective regarding blood pressure control.

How should one manage patients that do not tolerate renin-angiotensin system blockade? From the report of Chrysochou noted above, a modest number of patients (n=21) failed to tolerate RAAS blockade due to acute deterioration of GFR. Of that group, 16 were revascularized and tolerated re-introduction of these agents without difficulty (14). A separate report indicated that patients with RVH had prolonged QT intervals during medical therapy as compared to essential hypertension (17). Twenty-four of these underwent renal artery stenting with normalization of the QT interval. Patients from these studies represent subgroups for which renal revascularization plays an important role in management.

Does medical therapy lead to deterioration of kidney function related to ischemic nephropathy? Experimental studies in rats indicate that despite reduction in blood flow, cortico-medullary oxygen gradients often remain stable in RVD (18). Human studies using single-kidney measures of cortical and medullary perfusion combined with Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) magnetic resonance (MR) also demonstrate preservation of tissue oxygenation in human subjects with moderate RVD during antihypertensive drug therapy [See accompanying review of BOLD MR by Gloviczki] (19). Mean oscillometric systolic blood pressure levels averaged 130/70 mm Hg during these studies. The authors argue that even RVD sufficient to reduce blood flow and GFR and to activate the renin-angiotensin system can be associated with preserved tissue oxygenation. These findings may explain the relative stability of renal function observed in many medically treated patients with moderate renovascular hypertension, as reported in ASTRAL.

A subsequent report from the same group identified patients with more severe renovascular occlusion that developed overt cortical hypoxia and widening “fractional tissue” hypoxia in during antihypertensive drug therapy (20). For such patients, severely reduced blood flows overwhelm “adaptive” mechanisms and produce true hypoxia. Recent studies that included transjugular kidney biopsies obtained from patients with moderate and more severe RVD demonstrate accumulation of inflammatory macrophages, T-lymphocytes and widespread activation of fibrogenic cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β (21). Taken together, these studies do suggest that reductions in blood flow eventually reach and exceed the limits of tolerability leading to tissue hypoxia, inflammatory injury and kidney damage.

How often does medical therapy fail to adequately control blood pressure? This is difficult to establish from published reports. Fifty-two patients were reported that presented to emergency facilities with either hypertensive emergencies (n=13), hypertensive “urgency” (n=25), or symptomatic angina (n=13) (7). The blood pressure response to revascularization in these patients was predicted most accurately by the number of pre-treatment medications, while symptomatic angina was a negative predictor of BP response.

Interventional therapy for Renal Artery Stenosis

Results from the prospective trials reported up to 2010 failed to identify advantages of renal revascularization as compared to medical therapy, either for blood pressure control or renal functional recovery. These results have shifted the bias away from interventional procedures such as stent therapy. In both ASTRAL and STAR no differences in blood pressure or renal function were identified during follow-up in the stented group as compared to those treated with medical therapy alone. These trials have been criticized for selection bias related to inclusion of patients with minor renovascular disease (6)(22).

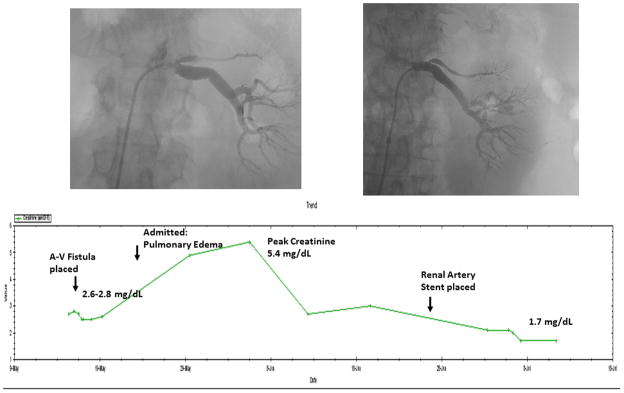

“Flash pulmonary edema” sometimes develops in patients with RVH. FIGURE. Mechanisms underlying a sudden development of circulatory congestion include a rapid rise of arterial pressure—and therefore afterload—that leads to precipitous ventricular dysfunction and a rise in pulmonary pressures (23). For these individuals, medical therapy often is associated with treatment failure, whereas successful renal revascularization is associated with reduced recurrence and hospitalization episodes (23) (9). One such case had marked improvement in blood pressure levels associated with an increase in cardiac ejection fraction from 39 to 65%, and reduced left ventricular mass (24). A separate report by ven den Berg, et.al. summarized reports of renal revascularization for RVD associated with congestive heart failure (5). The authors included 25 articles identifying 79 patients with RVD and “flash” pulmonary edema and an additional seven with 94 patients identified with RVD, congestive heart failure (CHF) and renal insufficiency. Seventy-six percent of subjects had no further episodes of flash pulmonary edema after technically successful revascularization. Recurrent symptoms were associated with arterial restenosis or cardiac arrhythmias. Overall severity of heart failure symptoms, usually expressed as New York Heart Association functional class improved after revascularization. While the authors classify the level of evidence as “low”, few clinicians would dispute the major therapeutic benefits of renal revascularization for some individuals experiencing recurrent episodes of circulatory congestion with bilateral RVD or stenosis to a solitary functioning kidney. [see FIGURE ].

Figure.

Serum creatinine values during a 6 week time period obtained for a 62 y.o. diabetic patient with morbid obesity. The rise in creatinine to 2.6 mg/dL had been attributed to diabetes, hypertension and obesity, leading to creation of an arterio-venous dialysis fistula as part of chronic kidney disease (CKD) management. After hospitalization for accelerated hypertension, pulmonary edema and worsening renal failure, she was identified as having a solitary functioning kidney with high-grade renal artery stenosis. Renal revascularization after withholding ACE inhibition led to a decline in creatinine to stable levels of 1.7 mg/dL, now stable for two years. For such patients, renal revascularization can offer recovery and stabilization of kidney function, allow therapy with ACE inhibition, and improve survival.

Does renal artery stenting improve kidney function in patients with “ischemic nephropathy”? Changes in renal function were the endpoints for several of the negative trials, including STAR and ASTRAL. However, one can question whether modest effects on renal function (these recent trials set the goal of detecting a 20% change) actually be identified using current methods, particularly in an asymmetric disorder such as RVD. Prospectively obtained estimates of GFR using several prediction equations (MDRD, CKD –EPI, 1/Screatinine, and Cockcroft-Gault) were reported from 254 patients examined repeatedly to obtain 541 measurements. These estimates were compared with near simultaneous formal measurements of GFR using iothalamate clearances as a measure of GFR specifically to examine whether these measurements could reliably identify a 20% change in function proposed as an outcome measure. Although group mean values were similar with these methods (average values ranged 48.8 to 53.2 ml/min/1.72m2) and correlations yielded R2 values between 0.76 and 0.83) classification of stages for CKD was poor, leading to misclassification in 24.6 to 33.3% of subjects (25). Perhaps most problematic was the error in determining trends and magnitude of change on serial measurements, with R2 values falling to between 0.31 and 0.33. The actual direction of change (i.e. whether GFR was actually increasing or decreasing) was discordant between estimates and measured values in 28 to 40% of cases. Part of these discordant estimates may reflect the recognized variability in serum creatinine in renovascular disease. Some would argue that these results fatally undermine the validity of eGFR as a method to evaluate changes in kidney function at these levels (26).

Changing concepts of injury from Renovascular Disease

Perhaps the most important lesson from recent studies of atherosclerotic RAS is the recognition of the limits of adaptation with more severe vascular occlusion leading ultimately to overt hypoxia and activation of inflammatory injury pathways as part of microvascular rarefication. Studies of human kidney biopsies and nephrectomy samples indicate accumulation of inflammatory macrophages with more advanced disease and activation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) associated with elevated renal vein cytokine markers suggestive of tissue inflammation (21)(27). Avoiding the downstream effects of TGF-β by studying a Smad3 knockout mouse strain demonstrated remarkable protection from histologic injury in a murine model (28). Kotliar, et. al. presented a series of vascular samples obtained from human subjects with atherosclerotic RVD. These samples contained increased numbers of T-cells with CD3, CD4, CD83 and CD86 characteristics in early atherosclerotic vascular lesions as well in peripheral blood (29). Taken together, these studies suggest activation of immune pathways, both in vascular tissue and in the kidney parenchyma, during the course of developing atherosclerotic RVD. Once these pathways have been activated, restoring renal blood flow alone by renal artery stenting is associated with persistent cortical atrophy in swine models (30). Such experimental studies extend and reinforce prior reports of progressive renal injury despite restoration of blood flow reported after both surgical (31) and/or endovascular treatment (32).

Several recent experimental studies indicate that reversing microvascular loss and inflammatory injury can be achieved by addressing these pathways directly. Intra-renal administration of vascular endothelial-derived growth factor (VEGF) is associated with recovery of renal blood flow and function in a swine model of atherosclerotic RAS (33). Previous studies suggest that even without revascularization, direct renal administration of endothelial progenitor cells alone is capable of inducing microvascular repair (34). Similarly, arterial infusion of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells is associated with restoration of microvascular structures and improvement in kidney function not attainable with restoring blood flow alone (35). MSC treatment is associated with measurable reductions in oxidative stress, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) that were not observed with revascularization alone. Measurement of tissue fibrosis and the number of apoptotic cells is substantially lower in animals treated with PTRA combined with MSC as compared to those with PTRA alone. These data argue that multiple injury pathways within the kidney parenchyma can be modulated by co-administration of MSC to restore microvascular and functional integrity that is not achieved with revascularization alone.

Whether the sudden restoration of blood flow associated with renal artery stenting induces “ischemia-reperfusion” injury in chronic renovascular disease has not been well-defined. Administration of an intravenous mitochondrial transition pore (MTP) inhibitor at the time of revascularization does indeed lead to improved recovery of renal vessels and function when studied a month later in the swine model (36). The fact that the MTP inhibitor administered just at the time of renal artery angioplasty was associated with improved renal microvascular structure, reduced apoptosis and lower oxidative stress injury implies that sudden renal reperfusion may have triggered kidney injury.

Conclusion: What is the current role of stent revascularization for the renal artery?

In view of the of prospective treatment trials and studies of preserved kidney oxygenation, most clinicians now favor initiating relatively aggressive antihypertensive therapy, including agents that block the renin-angiotensin system, and other measures to slow atherosclerosis for RVH. When blood pressure control is poorly achieved, when progressive loss of renal function is encountered, or when circulatory congestion is a prominent feature associated with stenosis to the entire functioning renal mass, many would argue that moving forward with renal revascularization offers an obvious therapeutic benefit. For patients with more severe vascular occlusion associated with overt tissue hypoxia and tissue inflammation, restoring renal blood flow in the main renal vessels sometimes fails to recover either kidney function or affect long-term outcomes. Further studies regarding the potential to reduce inflammatory injury and/or induce angiogenic repair within the microvessels of the kidney are fully warranted.

Key Points.

Recent trials support antihypertensive drug therapy as initial management for renovascular hypertension

Subsets of patients with refractory hypertension, episodes of pulmonary edema, and/or progressive renal failure may benefit from renal stenting

Although many patients preserve oxygenation, severe renovascular disease induces hypoxia and inflammatory injury that may progress despite restoration of vessel patency

Experimental studies indicate that cell-based therapy may assist repair of microvascular structures and recovery of kidney function

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by PO1HL85307 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Research Resources CTSA grant UL1 RR024150. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

Reference List

- 1.Textor SC. Issues in renovascular disease and ischemic nephropathy: Beyond ASTRAL. Curr Opin Nephrol Hyper. 2011;20:139–145. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328342bb35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foy A, Ruggiero NJ, Filippone EJ. Revascularization in renal artery stenosis. Cardiology in review. 2012;20(4):189–193. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e31824a72e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3*.Escobar GA, Campbell DN. Randomized trials in angioplasty and stenting of the renal artery: tabular review of the literature and critical analysis of their results. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26(3):434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.11.003. Thoughtful, current summary of the prospective trials in renal revascularization, including those with balloon angioplasty and the stenting trials. The authors delineate the entrance criteria, exclusions and caveats in interpretation needed to apply these data to patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumbhani DJ, Bavry AA, Harvey JE, et al. Clinical outcomes after percutaneous revascularization versus medical management in patients with significant renal artery stenosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;161:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5*.van den Berg DT, Postma CT, van der Wilt GJ, Riksen NP. The efficacy of renal angioplasty in patients with renal artery stenosis and flash oedema or congestive heart failure: a systematic review. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2012;14(7):773–781. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs037. Literature review of trials reports related to renal artery stenting in patients with congestive heart failure and/or episodic pulmonary edema. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White CJ. The need for randomized trials to prove the safety and efficacy of parachutes, bulletproof vests, and percutaneous renal intervention. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2011;86:603–605. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modrall JG, Rosero EE, Timaran CH, et al. Assessing outcomes to determine whether symptoms related to hypertension justify renal artery stenting. J Vasc surg. 2012;55(2):413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazza A, Rigatelli G, Piva M, et al. In high risk hypertensive subjects with incidental and unilateral renal artery stenosis, percutaneous revascularization with stent improves blood pressure control but not the glomerular filtration rate. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2011;59(6):533–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kindo M, Gerelli S, Billaud P, Mazzucotelli JP. Flash pulmonary edema in an orthotopic heart transplant recipient. Interactive Cardiovascular & Thoracic Surgery. 2011;12(2):323–325. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.254755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossi GP, Seccia TM, Miotto D, et al. The medical and endovascular treatment of atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (METRAS) study: rationale and study design. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26(8):507–516. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourantas CV, Loh HP, Lukaschuk EI, et al. Renal artery stenosis: an innocent bystander or an independent predictor of worse outcome in patients with chronic heart failure? a magnetic resonance imaging study. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2012;14(7):764–772. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mousa AY, Campbell JE, Stone PA, et al. Short and long-term outcomes of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty/stenting of renal fibromuscular dysplasia over a ten-year period. J Vasc surg. 2012;55(2):421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused update of the Guideline for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(19):2020–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Chrysochou C, Foley RN, Young JF, et al. Dispelling the myth: the use of renin-angiotensin blockade in atheromatous renovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(4):1403–1409. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr496. Excellent analysis of registry data underscoring the tolerability of renin-angiotensin system blockade in patients with renovascular disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hackam DG, Duong-Hua ML, Mamdani M, et al. Angiotensin inhibition in renovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Am Heart J. 2008;156:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bramlage C, Cuneo A, Hartel D, et al. Renal artery stenosis: angioplasty or drug treatment. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 2011;136:76–81. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maule S, Bertello C, Rabbia F, et al. Ventricular repolarization before and after treatment in patients with secondary hypertension due to renal artery stenosis and primary aldosteronism. Hypertension Research - Clinical & Experimental. 2011;34(10):1078–1081. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rognant N, Guebre-Egziabher F, Bachetta J, et al. Evolution of renal oxygen content measured by BOLD MRI downstream in a chronic renal artery stenosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1205–1210. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Gloviczki ML, Glockner JF, Lerman LO, et al. Preserved oxygenation despite reduced blood flow in poststenotic kidneys in human atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Hypertension. 2010;55(4):961–966. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145227. Carefully conducted studies in human subjects with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. These data apply blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) MR to demonstrate well-preserved cortical and medullary oxygen levels despite substantial reduction in blood flow and kidney size for most individuals. These observations partly explain the stability of kidney function in patients treated medically in the ASTRAL trial. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Gloviczki ML, Glockner JF, Crane JA, et al. Blood oxygen level-dependent magnetic resonance imaging identifies cortical hypoxia in severe renovascular disease. Hypertension. 2011;58:1066–1072. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171405. Carefully conducted studies identifying the development of overt cortical hypoxia when severe renovascular disease lowers kidney blood flow beyond the limits tolerated by “adaptation”. These data emphasize the use of Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) MR in renovascular disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Gloviczki ML, Keddis MT, Garovic VD, et al. TGF expression and macrophage accumulation in atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:999. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06460612. ePub ahead of print. Human studies of tissue obtained by transjugular biopsy and nephrectomy specimens that demonstrate activation of transforming growth factor-beta and macrophage accumulation in post-stenotic kidneys. These data argue that inflammatory pathways mediate tissue injury and may explain progressive disease despite restoring vessel patency in some patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann SJ, Sos TA. Misleading results of randomized trials: the example of renal artery stenting. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12:1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2009.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Makani H, et al. Flash pulmonary oedema and bilateral renal artery stenosis: the Pickering Syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(18):2231–2237. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr056. Pathophysiologic dissection of mechanisms identified to underly rapid development of pulmonary edema in patients with renovascular disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chrysochou C, Schmitt M, Siddals K, et al. Reverse cardiac remodelling and renal functional improvement following bilateral renal artery stenting for flash pulmonary oedema. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr745. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madder RD, Hickman L, Crimmins GM, et al. Validity of estimated glomerular filtration rates for assessment of baseline and serial renal function in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: implications for clinical trials of renal revascularization. Circulation: Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:219–225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.960971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Textor SC. Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: flaws in estimated glomerular filtration rate and the problem of progressive kidney injury. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:213–215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.962795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Eirin A, Gloviczki ML, Tang H, et al. Inflammatory and injury signals released from the post-stenotic human kidney. Europ Heart J. 2013;34(7):540–548. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs197. Original study of renal vein cytokine profiles obtained from patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease demonstrating elevated cell adhesion molecules and inflammatory signalling in both stenotic and contralateral kidneys, far greater than essential hypertension. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warner GM, Cheng J, Knudsen BE, et al. Genetic deficiency of Smad3 protects the kidneys from atrophy and interstitial fibrosis in 2K1C hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(11):F1455–F1464. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00645.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotliar C, Juncos L, Inserra F, et al. Local and systemic cellular immunity in early renal artery atherosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:224–230. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06270611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eirin A, Zhu XY, Urbieta-Caceres VH, et al. Persistent kidney dysfunction in swine renal artery stenosis correlates with outer cortical microvascular remodeling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F1394–F1401. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00697.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherr GS, Hansen KJ, Craven TE, et al. Surgical management of atherosclerotic renovascular disease. J Vasc surg. 2002;35:236–245. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.120376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Textor SC, Misra S, Oderich G. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic nephropathy: the past, present and future. Kidney International. 2013;83(1):28–40. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chade AR, Kelsen S. Reversal of renal dysfunction by targeted administration of VEGF into the stenotic kidney: a novel potential therapeutic approach. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(10):F1342–F1350. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00674.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34**.Chade AR, Zhu X, Lavi R, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells restore renal function in chronic experimental renovascular disease. Circulation. 2009;119:547–557. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788653. Important experimental study demonstrating potential for circulating pluripotent progenitor cells to shape recovery of viable blood vessels, improve filtration and restore tubular function in kidneys that are undergoing vascular rarefaction beyond a renal artery stenosis. These data provide a rationale for considering stem cell as an adjunctive maneuver in recovering kidney structure in ischemic renal disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35**.Eirin A, Zhu XY, Krier JD, et al. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve revascularization outcomes to restore renal function in swine atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Stem Cells. 2012;30(5):1030–1041. doi: 10.1002/stem.1047. Important experimental study demonstrating ability of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) to restore microvessel integrity and kidney function in conjunction with renal revascularization in a swine model. These data argue that inflammatory injury can be reversed using the immunomodulatory and angiogenic effects of MSC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36**.Eirin A, Li Z, Xhang X, et al. A mitochondrial permeability transition pore inhibitor improves renal outcomes after revascularization in experimental atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Hypertension. 2012;60:1242–1249. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.199919. Additional experimental study utilizing an investigational mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) inhibitor at the time of renal revascularization that improved microvascular structure, reduced tissue oxidative stress markers and apoptosis 4 weeks later. These data provide indirect support for the concept of ischemia-reperfusion injury associated with renal revascularization for chronic renal arterial disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]