Abstract

We investigated the effects of an acute bout of neuromuscular electrical stimulation–induced resistance exercise (NMES-RE) on intracellular signaling pathways involved in translation initiation and mechanical loading–induced muscle hypertrophy in spinal cord–injured (SCI) versus able-bodied (AB) individuals. AB and SCI individuals completed 90 isometric knee extension contractions at 30% of maximum voluntary or evoked contraction, respectively. Muscle biopsies were collected before, and 10 and 60 min after NMES-RE. Protein levels of α7- and β1-integrin, phosphorylated and total GSK-3α/β, S6K1, RPS6, 4EBP1, and FAK were assessed by immunoblotting. SCI muscle appears to be highly sensitive to muscle contraction even several years after the injury, and in fact it may be more sensitive to mechanical stress than AB muscle. Heightened signaling associated with muscle mechanosensitivity and translation initiation in SCI muscle may be an attempted compensatory response to offset elevated protein degradation in atrophied SCI muscle.

Keywords: mechanotransduction, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, resistance exercise, skeletal muscle, spinal cord injury

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation–induced resistance exercise (NMES-RE) training promotes robust muscle hypertrophy in spinal cord–injured (SCI) individuals,1,2 which may be very important for overall metabolic health as these patients age. The mechanisms by which this remarkable hypertrophy occurs in paralyzed muscle remain unclear. Net protein synthesis required for muscle hypertrophy is regulated primarily by translation initiation. Signaling pathways that modulate translation initiation are sensitive to many stimuli, including the mechanical forces of muscle contraction.3 We recently reported NMES-RE–mediated phosphorylation of p44/42 extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) and Akt in SCI but not in ablebodied (AB) men,4 suggesting that skeletal muscles of SCI men may be more sensitive to mechanical loading.5 As a follow-up to our previous work, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of SCI on a key mechanotransduction protein (α7-integrin) and an acute bout of NMES-RE on putative intracellular signaling pathways involved in translation initiation and mechanical loading–induced muscle hypertrophy in SCI versus AB men.

METHODS

AB and SCI individuals performed 90 isometric knee extension contractions at 30% of maximum voluntary or evoked contraction, respectively. Muscle samples were collected from the vastus lateralis before and 10 and 60 min after NMES-RE via our established percutaneous needle biopsy procedure.6 Mixed muscle protein lysates from 8 of the original 12 SCI men (injury levels, C4–T8, American Spinal Injury Association grade A and B, 22.2 ± 11 years post-injury, 49.6 ± 11 years of age) and 9 AB men (aged 46.5 ± 9 years) were analyzed. Analyses were limited by remaining lysate availability (details of subject characteristics and NMES-RE protocol are published in our previous report4).

Immunoblotting

Thirty-five micrograms of skeletal muscle mixed protein lysate were resolved on 4–12% sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, as described previously.7,8 Primary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, Massachusetts) and used at a 1:1000 dilution in 5% goat serum (monoclonal antibodies) or 2% milk + 2% bovine serum albumin (polyclonal antibodies) against: total and phospho GSK-3α/β (Ser21/9); p70 S6K1 (Thr421/Ser424); ribosomal protein S6 [RPS6 (Ser240/244)]; 4EBP1 (Thr37/46); FAK (Tyr397); and total β1-integrin. Anti–α7-integrin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California) and used at a 1:200 dilution in 5% goat serum. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies were used at 1:50,000 followed by chemiluminescent detection (SuperSignal West Dura Chemiluminescent Substrate; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, Illinois).

Statistical Analysis

Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test group × time interactions and main effects of time and group. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Translation Initiation

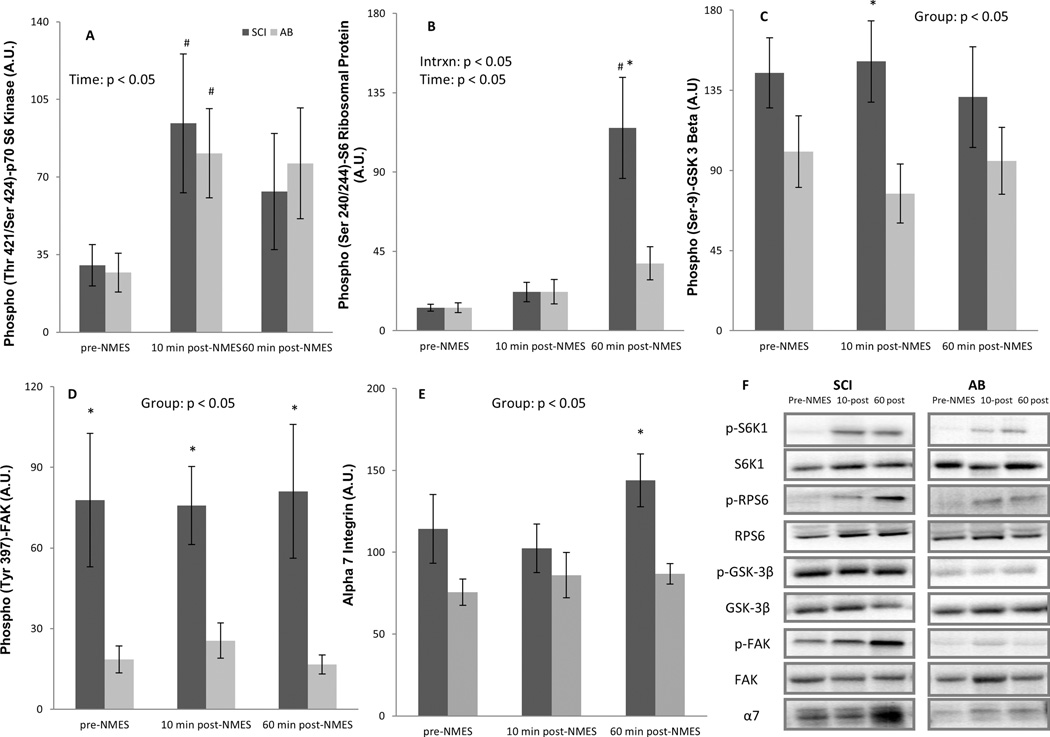

Both groups demonstrated main effects of time (P < 0.05) for S6K1 (Thr421/ Ser424). S6K1 phosphorylation was elevated above baseline (P < 0.05) at 10 min post–NMES-RE in both groups (Fig. 1A). A group × time interaction (P < 0.05), and main effects of time (P < 0.05) and group (P < 0.05) were noted for RPS6 phosphorylation (Ser240/244) (Fig. 1B). In SCI, RPS6 phosphorylation was elevated robustly above baseline (P < 0.05) 60 min after NMES-RE and was higher (P < 0.05) in SCI than in AB at 60 min post– NMES-RE. A main group effect (P < 0.05) revealed a higher phosphorylation state of GSK-3β (Ser9) (Fig. 1C) in SCI compared with AB subjects. Within time-points, post hoc tests indicated higher GSK-3β phosphorylation at 10 min post-NMES. No interaction or main effects were found for total and phosphorylation levels of 4EBP1 (not shown) and total levels of S6K1, RPS6, or GSK-3β.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of an acute bout of NMES-RE on phosphorylation and/or total levels of S6K1 (A), RPS6 (B), GSK-3β (C), FAK (D), and α7-integrin (E). (F) Representative immunoblots. Bars represent mean ± SE. Significant main effects and interaction (Intrxn) terms of time × group ANOVA are shown in (A)–(E). #P < 0.05: different from baseline within group, *P < 0.05: different from AB. AU, arbitrary units.

Mechanosensitivity

A main group effect (P < 0.05) revealed a higher phosphorylation state of FAK (Tyr397) for SCI compared with AB. Post hoc tests indicated higher FAK phosphorylation in SCI subjects at all time-points (Fig. 1D). Moreover, a main group effect (P < 0.05) for α7-integrin (Fig. 1E) indicated higher levels in SCI overall (P < 0.05), particularly at 60 min post-NMES.

DISCUSSION

The primary and novel finding of this study is that SCI muscle appears to be highly sensitive to muscle contraction even 22 years after the injury, and in fact it may be more sensitive to mechanical stress than AB muscle. Our findings of higher FAK phosphorylation and total levels of α7-integrin in SCI are consistent with this idea. FAK is associated with the cytosolic domain of β1-integrin of the α7– β1-integrin heterodimer and is therefore thought to be a key mechanosensitive signaling molecule, converting mechanical stimuli to anabolic signaling in skeletal muscle.9,10 Phosphorylated FAK has been shown to activate a number of signaling cascades, including MEK-ERK and PI3K-Akt. Hyperphosphorylation of FAK shown here may thus be at least partially responsible for the NMES-RE induction of these 2 pathways only in SCI muscle.

Although NMES-RE led to similar increases in S6K1 phosphorylation in both SCI and AB, downstream phosphorylation of RPS6 was noted only in SCI individuals. The mechanism underlying this differential response is not known; however, because we assayed the S6K1 auto-inhibitory domain (Thr421/Ser424), and subsequent phosphorylation events are required for full S6K1 activation, it is possible that full activation was only achieved in SCI muscle. Recent findings suggest a potential direct link between FAK and S6K1 activity, such that overexpression of FAK has been shown to enhance load-mediated S6K1 phosphorylation.9 GSK-3β is a putative inhibitor of translation initiation by impeding eIF2B signaling, and this inhibition is removed upon GSK-3β phosphorylation. Thus, the hyperphosphorylated state of GSK- 3β found in SCI muscle would presumably favor protein synthesis. It is unclear why these SCI muscles appear to be more mechanosensitive and/or more pro-anabolic. This could not be attributed to spontaneous contractures or spasticity because: (1) muscle contractures were an exclusion criterion; (2) only 2 subjects used anti-spasticity medication regularly; and (3) none of the subjects had leg spasticity during NMES-RE. We offer 2 other possibilities, each of which would require further study. First, SCI muscle may be in a heightened compensatory state in an attempt to offset elevated protein degradation, as suggested by elevated catabolic gene expression and signaling reported elsewhere.11,12 Second, the differences between SCI and AB muscle described here may have been influenced by muscle fiber type distribution. Findings from previous work have shown higher phosphorylation states of mechanosensitive proteins in fast muscles in response to mechanical stress.5 We previously reported remarkable group differences in fiber type distribution4; compared with AB, SCI muscle had a predominance of IIax + IIx fibers.

Surprisingly, NMES-RE did not alter many measured indices of intracellular signaling among AB subjects. When considering the findings in previous studies,13–15 it is possible that dynamic contractions are a more potent stimulus for these signaling pathways than are isometric contractions. Although isometric contractions induced via NMES represent a relatively small fraction of the activity and daily loading in AB subjects, NMES promotes robust muscle hypertrophy in SCI. This increase in muscle mass may result in increased levels of metabolically active muscle tissue, which can improve glucose tolerance and reduce metabolic disease risk in SCI individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the participants for their tireless dedication. We also than S.C. Tuggle for assistance with project coordination.

This work was supported by a VA Merit Award (to M.M.B.); the UAB Center for Exercise Medicine, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (5T32 DK62710); and the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1 TR000165).

Abbreviations

- AB

able-bodied

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ERK

extracellular signal–regulated kinase

- NMES-RE

neuromuscular electrical stimulation–induced resistance exercise

- SCI

spinal cord injured

REFERENCES

- 1.Bickel CS, Slade JM, Haddad F, Adams GR, Dudley GA. Acute molecular responses of skeletal muscle to resistance exercise in able-bodied and spinal cord-injured subjects. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:2255–2262. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00014.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudley GA, Castro MJ, Rogers S, Apple DF., Jr A simple means of increasing muscle size after spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1999;80:394–396. doi: 10.1007/s004210050609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolster DR, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Regulation of protein synthesis associated with skeletal muscle hypertrophy by insulin-, amino acid- and exercise-induced signalling. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:351–356. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarar-Fisher C, Bickel CS, Windham ST, McLain AB, Bamman MM. Skeletal muscle signaling associated with impaired glucose tolerance in spinal cord-injured men and the effects of contractile activity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;115:756–764. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00122.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martineau LC, Gardiner PF. Insight into skeletal muscle mechano-transduction: MAPK activation is quantitatively related to tension. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2001;91:693–702. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamman MM, Ragan RC, Kim JS, Cross JM, Hill VJ, Tuggle SC, et al. Myogenic protein expression before and after resistance loading in 26- and 64-yr-old men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1329–1337. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01387.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayhew DL, Hornberger TA, Lincoln HC, Bamman MM. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2B epsilon induces cap-dependent translation and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Physiol. 2011;589:3023–3037. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.202432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thalacker-Mercer AE, Dell’Italia LJ, Cui X, Cross JM, Bamman MM. Differential genomic responses in old vs. young humans despite similar levels of modest muscle damage after resistance loading. Physiol Genomics. 2010;40:141–149. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00151.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klossner S, Durieux AC, Freyssenet D, Flueck M. Mechano-transduction to muscle protein synthesis is modulated by FAK. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:389–398. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lueders TN, Zou K, Huntsman HD, Meador B, Mahmassani Z, Abel M, et al. The alpha7beta1-integrin accelerates fiber hypertrophy and myogenesis following a single bout of eccentric exercise. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C938–C946. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00515.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batt J, Bain J, Goncalves J, Michalski B, Plant P, Fahnestock M, et al. Differential gene expression profiling of short and long term denervated muscle. FASEB J. 2006;20:115–117. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3640fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urso ML, Chen YW, Scrimgeour AG, Lee PC, Lee KF, Clarkson PM. Alterations in mRNA expression and protein products following spinal cord injury in humans. J Physiol. 2007;579:877–892. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreyer HC, Fujita S, Glynn EL, Drummond MJ, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Resistance exercise increases leg muscle protein synthesis and mTOR signalling independent of sex. Acta Physiol. 2010;199:71–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayhew DL, Kim JS, Cross JM, Ferrando AA, Bamman MM. Translational signaling responses preceding resistance training-mediated myofiber hypertrophy in young and old humans. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1655–1662. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91234.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terzis G, Georgiadis G, Stratakos G, Vogiatzis I, Kavouras S, Manta P, et al. Resistance exercise-induced increase in muscle mass correlates with p70S6 kinase phosphorylation in human subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;102:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0564-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]