Abstract

Nearly all mitochondrial proteins are nuclear-encoded and are targeted to their mitochondrial destination from the cytosol. Here, we used proximity-specific ribosome profiling to comprehensively measure translation at the mitochondrial surface in yeast. Most inner membrane proteins were co-translationally targeted to mitochondria, reminiscent of proteins entering the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Comparison between mitochondrial and ER localization demonstrated that the vast majority of proteins were targeted to a specific organelle. A prominent exception was the fumarate reductase Osm1, known to reside in mitochondria. We identified a conserved ER isoform of Osm1, which contributes to the oxidative protein folding capacity of the organelle. This dual localization was enabled by alternative translation initiation sites encoding distinct targeting signals. These findings highlight the exquisite in vivo specificity of organellar targeting mechanisms.

The vast majority of mitochondrial proteins (~99% in Saccharomyces cerevisiae) are encoded in the nuclear genome (1). These proteins are translated in the cytosol and must be sorted into the matrix, inner membrane (IM), intermembrane space (IMS), and outer membrane (OM) of the mitochondrion by a network of channels and chaperones. While the predominant view is that protein import into mitochondria occurs post-translationally on unfolded polypeptides, co-translational translocation has been demonstrated for some substrates (2). Moreover, ribosomes have been observed on the OM by electron microscopy (3) and numerous mRNAs associate closely with mitochondria (4–6), consistent with a broader role for co-translational protein insertion.

To directly evaluate which proteins are translated on the surface of mitochondria in an unperturbed context, we applied the proximity-specific ribosome profiling technique (7). This approach involves in vivo biotinylation of Avi-tagged ribosomes that are in contact with a spatially localized biotin ligase (BirA), followed by affinity purification of biotinylated ribosomes and readout of translational activity by deep sequencing of ribosome-protected fragments. To mark ribosomes selectively on the mitochondrial surface, we fused BirA to the C-terminus of OM45, a major component of the OM (Fig. 1A). Whereas a cytosolic BirA efficiently labeled both Avi-tagged large (Rpl16/uL13) and small (Rps2/uS5) subunits (7), Om45-BirA only biotinylated the large subunit indicating that labeled ribosomes were constrained at the mitochondria with their peptide exit tunnels facing the OM (Fig. 1B). This pattern was observed for co-translational import at the ER (7), arguing that ribosomes marked by Om45-BirA are engaged in protein translocation.

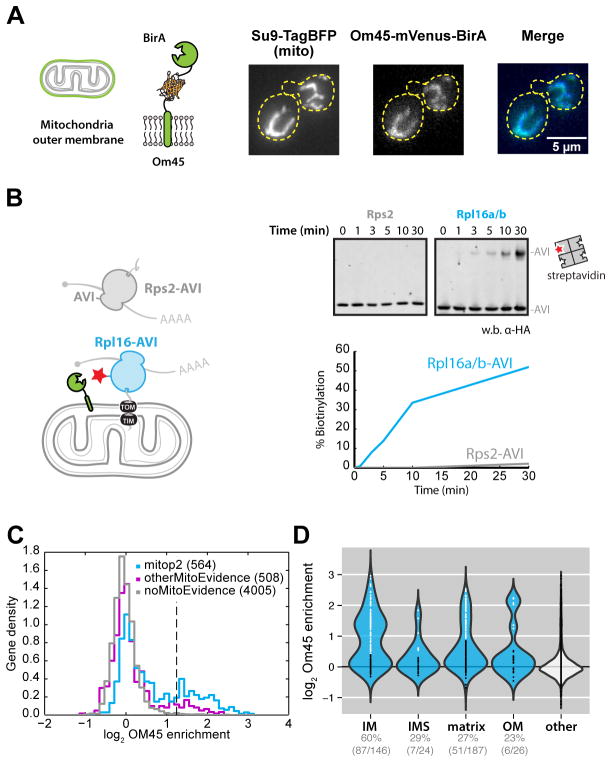

Fig. 1. Cotranslational mitochondrial protein targeting as revealed by proximity-specific ribosome profiling.

(A) Localization of biotin ligase to the outer membrane. Schematic of the Om45 fusion protein and confocal fluorescence images of Om45-mVenus-BirA and Su9-TagBFP are shown. (B) Assessment of ribosome orientation at the mitochondrial outer membrane. The kinetics of Avi-tagged Rps2 (gray) and Rpl16a/b (blue) biotinylation by Om45-mVenus-BirA were determined by western blot analysis of streptavidin-shift gels. (C) Histogram of log2 ratios for biotinylated footprints/input footprints in the absence of CHX. Genes annotated in the mitop2 reference set are shown in blue and enrichment threshold is shown as a dashed vertical line. Genes with mitochondrial GO cellular component terms not in mitop2 are shown in magenta. (D) Violin plot showing log2 gene enrichments for proteins grouped by their annotated location within mitochondria in the absence of CHX arrest. Gene enrichments are overlaid as points, with white and black colors indicating enrichment or disenrichment, respectively, as determined by sub-compartment-specific Gaussian mixture modeling (fig. S2A) and quantified below the plot.

Proximity-specific profiling experiments were performed with a brief (2 min) pulse of biotin in the absence of any translation inhibitors, to preserve the in vivo rates of translation and targeting. Of the enriched genes (fig. S1A), 87% were annotated as mitochondrial and a clear subset of expressed mitop2 (1) mitochondrial reference genes (156 out of 551) were cotranslationally targeted (Fig. 1C and table S1). Each mitochondrial sub-localization was significantly enriched in cotranslationally targeted proteins (P < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test). The IM proteins were distinct among sublocalizations (Fig. 1D); most IM proteins were cotranslationally targeted, whereas smaller subsets of OM, IMS and matrix proteins were enriched (fig. S2A). By virtue of their transmembrane domains (TMDs), the IM proteins must simultaneously avoid aggregation in the cytosol and errant integration into other membranes. Co-translational insertion may minimize the potential for toxicity associated with the accumulation of membrane proteins in the cytosol (8).

Omission of translation elongation inhibitors in the above experiments allowed us to define the proteins that were unambiguously translated at the mitochondrial surface. However, these were only a subset of the mRNAs that purify with mitochondria in the presence of the translation elongation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) (table S1) (5). We reasoned that by providing a prolonged time for ribosome–nascent chains (RNCs) to engage mitochondria, CHX pretreatment would yield a more comprehensive view of the mitochondrial proteome. Indeed, when we included CHX, we maintained mitochondrial specificity (fig. S1, B and C) but observed a large increase in the number of enriched proteins (Fig. 2A). For example, 68% (131 out of 191) of the mitop2-annotated matrix proteins were enriched compared to 27% (51 out of 187) without CHX (Figs. 2B and 1D).

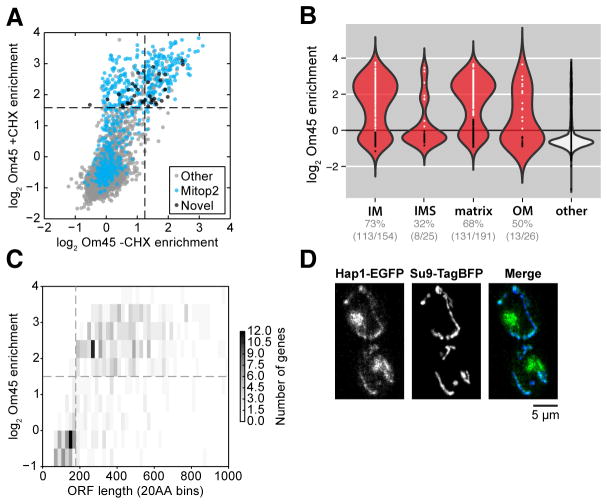

Fig. 2. Comprehensive characterization of RNC targeting to the mitochondria.

(A) Scatter plot of log2 gene enrichments for footprints from ribosomes biotinylated by Om45-mVenus-BirA in the presence or absence of CHX. Novel genes represent those that were significantly enriched but had no known mitochondrial annotations. (B) Violin plot showing log2 gene enrichments for proteins grouped by their location within mitochondria in the presence of CHX arrest (as in Fig. 1D). Gene enrichments were determined by sub-compartment-specific Gaussian mixture modeling (fig. S2B). (C) Two-dimensional histogram of genes binned by open reading frame length compared to their log2 gene enrichment in the presence of CHX. (D) Epifluorescence microscopy of Hap1-EGFP and Su9-TagBFP.

We focused on the subset of genes that had a high probability of containing N-terminal mitochondrial matrix and IM protein targeting sequences (MTSs) as predicted by MitoProt (9). The bimodal distribution of enrichments for this group raised the question of why some RNCs were translocation incompetent. We observed a clear difference in protein size between the enriched and depleted matrix proteins; the large majority of RNCs observed at the mitochondria were more than ~180 codons in length (Fig. 2C and fig. S3).

Mitochondrial proteins were selectively enriched across a wide range of expression levels (fig. S1C). This sensitivity allowed for the identification of 39 candidate mitochondrial proteins translated at the OM with no prior mitochondrial annotation in mitop2, Gene Ontology (GO), or Yeast GFP databases (1, 10, 11) (Fig. 2A and table S1). These genes were more likely to contain MTSs, as predicted by Mitoprot (9), than non-enriched genes (P = 0.002, Mann-Whitney U test) (fig. S1D), supporting their candidacy as mitochondrial. Among this set was Hap1, a heme-responsive transcription factor (12). A Hap1-GFP (green fluorescent protein) fusion expressed from the endogenous locus was found both in the nucleus, as expected, and in the mitochondria as predicted by our translational enrichments (Fig. 2D). Heme biosynthesis occurs in the mitochondria and is regulated by Hap1. Because MTS-mediated import requires an energized IM, Hap1 localization may allow for direct sensing of mitochondrial integrity. Hap1 sequestration in mitochondria could allow the cell to tune nuclear transcriptional activity through Hap1 localization (13).

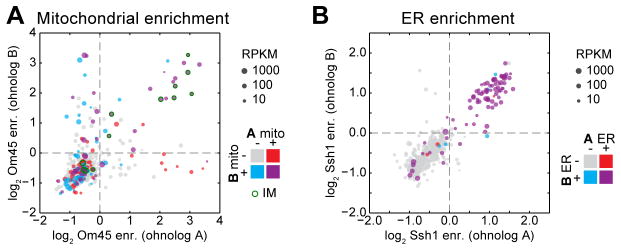

We next investigated the evolution of mitochondrial protein localization among paralogs. S. cerevisiae underwent a whole-genome duplication (WGD) ~100 million years ago, making it well suited for exploring changes in protein localization between duplicate paralogs (termed ohnologs) (14). With the exception of the IM proteins, we found notable fluidity in the targeting of ohnologs to mitochondria that was not due to disparity in expression levels (Fig. 3A). By contrast, targeting of ohnologs to the ER rarely showed discrepancies between paralog pairs (Fig. 3B), emphasizing the relative plasticity of the mitochondrial proteome. In contrast to proteins residing in the ER or mitochondrial IM, matrix and cytosolic proteins have similar environments, which would allow proteins to function in either location.

Fig. 3. Conservation of paralogous protein localization.

(A) Scatter plot of mitochondrial log2 gene enrichments for ohnolog pairs, whose x- and y-axis assignment is arbitrary. Color codes indicate the expected ohnolog localizations based on existing evidence consolidated from mitop2, GO, and GFP annotations. Point size represents minimum expression level between paralogs. (B) As in (A), for ER enrichments.

We further exploited our mitochondrial and ER protein localization data sets to explore the extent to which individual proteins show dual localization between the two intracellular sites. The close physical association of these organelles makes the biochemical isolation of pure mitochondria and microsomes challenging, confounding searches for dual-localization in such preparations. For example the ERMES complex, which tethers the ER and mitochondria (15), was originally thought to be exclusively mitochondrial. Proximity-specific ribosome profiling of the mitochondria and ER resolved components of the ERMES complex to their respective compartments, and provided highly specific catalogs of proteins at each organelle (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S4).

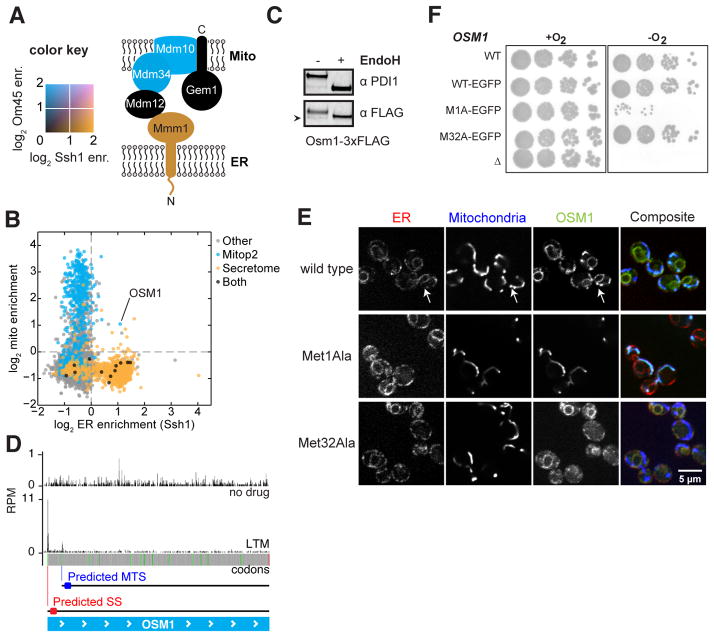

Fig. 4. Dual localization of proteins to the mitochondria and ER.

(A) The color-mapped log2 enrichments for ribosome labeling by Om45 (blue) and Ssh1 (orange) are overlaid for members of the ERMES complex. (B) Scatter plot of ER enrichments compared to mitochondrial enrichments in the presence of CHX. Points are colored by their annotated localization. (C) Western blot analysis of N-linked glycans. Extracts from cells expressing Osm1-3xFLAG were blotted for PDI1 or FLAG with or without EndoH treatment. Arrowhead indicates an Osm1 band migrating below the size of the deglycosylated protein. (D) Ribosome occupancy of Osm1 with or without LTM treatment. In-frame AUG codons are shown in green; predicted localization of proteins made from the indicated start codon are shown. (E) Confocal fluorescence microscopy of Osm1-EGFP localization compared to ER (Sec63-mCherry) or mitochondria (Su9-BFP). Wild type, Met1Ala, and Met32Ala variants of Osm1 are shown. (F) Analysis of signal requirements for Osm1 to support anaerobic growth as the sole fumarate reductase gene.

Very few proteins exhibited dual localization. Most proteins with both secretory and mitochondrial annotations (10) were cotranslationally inserted exclusively to the ER (Fig. 4B). Among the few counter examples was the fumarate reductase OSM1. Although several studies suggest that Osm1 localizes exclusively to the mitochondria (11, 16, 17), high-throughput studies hint at a possible ER function. Specifically, a genetic-interaction data set indicated that osm1Δ shows a synthetic sick phenotype with a hypomorphic temperature-sensitive allele of ERO1 (18) (fig. S5), the protein responsible for driving disulfide bond formation in the ER. Additionally, Osm1 is included in the N-glycoproteome, consistent with its entry into the secretory pathway (19). Our analysis of the glycosylation pattern of Osm1 and fluorescence microscopy of an endogenously expressed Osm1-GFP fusion proteins demonstrated that Osm1 is localized to both the ER and mitochondria (Fig. 4, C and E).

Given the exquisite specificity of the vast majority of ER signal sequences (SSs) and MTSs, how is Osm1 efficiently targeted to both organelles? Ribosome profiling experiments using lactimidomycin (LTM), which leads to the accumulation of ribosomes at translation start sites (20), revealed that OSM1 possesses two functional in-frame start codons predicted to encode either an ER (Met1) or MTS (Met32) signal (Fig. 4D). Mutation of the upstream methionine to alanine (Met1Ala) resulted in strict mitochondrial localization whereas the Met32Ala mutant localized exclusively to the ER (Fig. 4E).

Osm1 homologs, including those of non-WGD yeast species, are predicted to contain SSs (21) (fig. S6), emphasizing the conserved ER localization of this class of fumarate reductases. Given the genetic interaction between ERO1 and OSM1, an appealing function for this ER-localized form is to drive oxidative protein folding. Ero1 is a flavoprotein and its reoxidation, following disulfide bond catalysis, can be driven by oxidized FAD (22, 23). Furthermore, studies of oxidative folding under anaerobic conditions suggest that fumarate is the terminal electron acceptor and Osm1 generates free oxidized FAD via the reduction of fumarate (24). Consistent with this model, we found that the ER-form of Osm1 (Met32Ala) but not the mitochondrial-form (Met1Ala) supported growth under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 4F).

Proximity-specific ribosome profiling allowed us to elucidate several fundamental aspects of mitochondrial biogenesis. First, we discovered a major role for co-translational targeting, but one that is most prominent for IM proteins. Second, we found that ohnologs encoding soluble proteins exhibit a high degree of fluidity in their mitochondrial localization, facilitating the exchange of function between the mitochondrial matrix and the cytosol. This plasticity may have facilitated or have been driven by the metabolic changes associated with a switch toward preferring fermentation over respiration that occurred after the WGD in budding yeast (the Crabtree effect) (25). Third, we demonstrated the exquisite specificity of protein targeting to the ER versus mitochondria in vivo. How targeting factors, such as SRP (26) and NAC (27), act on diverse RNCs to create this specificity in vivo remains an open question.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 Comprehensive yeast annotation table

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Weissman and P. Walter labs for discussion and E. Costa and V. Okreglak for critical reading of the manuscript. The University of California, San Francisco, Center for Advanced Technology and Nikon Imaging Center provided technical support. We thank C. Policarpi for assistance in strain construction and pilot ribosome profiling experiments, G. Brar for sharing unpublished ribosome profiling data, P. Walter for use of the Su9-TagBFP plasmid, and J. Horst for assistance with anaerobic growth conditions and equipment. This research was supported by the Center for RNA Systems Biology and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. C.C.W. is an NSF Graduate Research Fellow. C.H.J. is the Rebecca Ridley Kry Fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-2085-11). Data are deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus under accession numbers GSE61011 and GSE61012.

References and Notes

- 1.Elstner M, Andreoli C, Klopstock T, Meitinger T, Prokisch H. The mitochondrial proteome database: MitoP2. Methods Enzymol. 2009;457:3–20. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox TD. Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis, Import, and Assembly. Genetics. 2012;192:1203–1234. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.141267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellems RE, Allison VF, Butow RA. Cytoplasmic type 80S ribosomes associated with yeast mitochondria. IV. Attachment of ribosomes to the outer membrane of isolated mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1975;65:1–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.65.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suissa M, Schatz G. Import of proteins into mitochondria. Translatable mRNAs for imported mitochondrial proteins are present in free as well as mitochondria-bound cytoplasmic polysomes. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13048–13055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marc P, et al. Genome-wide analysis of mRNAs targeted to yeast mitochondria. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:159–164. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saint-Georges Y, et al. Yeast Mitochondrial Biogenesis: A Role for the PUF RNA-Binding Protein Puf3p in mRNA Localization. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jan CH, Williams CC, Weissman JS. Principles of ER Co-Translational Translocation Revealed by Proximity-Specific Ribosome Profiling. Science (submitted) 2014 doi: 10.1126/science.1257521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandman O, et al. A Ribosome-Bound Quality Control Complex Triggers Degradation of Nascent Peptides and Signals Translation Stress. Cell. 2012;151:1042–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claros MG, Vincens P. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur J Biochem FEBS. 1996;241:779–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherry JM, et al. Saccharomyces Genome Database: the genomics resource of budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D700–705. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huh WK, et al. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarente L, Lalonde B, Gifford P, Alani E. Distinctly regulated tandem upstream activation sites mediate catabolite repression of the CYC1 gene of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1984;36:503–511. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nargund AM, Pellegrino MW, Fiorese CJ, Baker BM, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial Import Efficiency of ATFS-1 Regulates Mitochondrial UPR Activation. Science. 2012;337:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1223560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe K. Robustness--it’s not where you think it is. Nat Genet. 2000;25:3–4. doi: 10.1038/75560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kornmann B, et al. An ER-Mitochondria Tethering Complex Revealed by a Synthetic Biology Screen. Science. 2009;325:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1175088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muratsubaki H, Enomoto K. One of the Fumarate Reductase Isoenzymes from Saccharomyces cerevisiaeIs Encoded by theOSM1Gene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;352:175–181. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enomoto K, Arikawa Y, Muratsubaki H. Physiological role of soluble fumarate reductase in redox balancing during anaerobiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;215:103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costanzo M, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zielinska DF, Gnad F, Schropp K, Wiśniewski JR, Mann M. Mapping N-glycosylation sites across seven evolutionarily distant species reveals a divergent substrate proteome despite a common core machinery. Mol Cell. 2012;46:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stern-Ginossar N, et al. Decoding human cytomegalovirus. Science. 2012;338:1088–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1227919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrne KP, Wolfe KH. The Yeast Gene Order Browser: Combining curated homology and syntenic context reveals gene fate in polyploid species. Genome Res. 2005;15:1456–1461. doi: 10.1101/gr.3672305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross E, et al. Generating disulfides enzymatically: reaction products and electron acceptors of the endoplasmic reticulum thiol oxidase Ero1p. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:299–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506448103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu BP, Weissman JS. The FAD- and O2-Dependent Reaction Cycle of Ero1-Mediated Oxidative Protein Folding in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Mol Cell. 2002;10:983–994. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Österlund T, Hou J, Petranovic D, Nielsen J. Anaerobic α-Amylase Production and Secretion with Fumarate as the Final Electron Acceptor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:2962–2967. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03207-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomson JM, et al. Resurrecting ancestral alcohol dehydrogenases from yeast. Nat Genet. 2005;37:630–635. doi: 10.1038/ng1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akopian D, Shen K, Zhang X, Shan S. Signal Recognition Particle: An Essential Protein-Targeting Machine. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:693–721. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.del Alamo M, et al. Defining the Specificity of Cotranslationally Acting Chaperones by Systematic Analysis of mRNAs Associated with Ribosome-Nascent Chain Complexes. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Lim WA, Thorn KS. Improved Blue, Green, and Red Fluorescent Protein Tagging Vectors for S. cerevisiae. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okreglak V, Walter P. The conserved AAA-ATPase Msp1 confers organelle specificity to tail-anchored proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014:201405755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405755111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ast T, Cohen G, Schuldiner M. A Network of Cytosolic Factors Targets SRP-Independent Proteins to the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Cell. 2013;152:1134–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camarasa C, Faucet V, Dequin S. Role in anaerobiosis of the isoenzymes for Saccharomyces cerevisiae fumarate reductase encoded by OSM1 and FRDS1. Yeast Chichester Engl. 2007;24:391–401. doi: 10.1002/yea.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Comprehensive yeast annotation table