Abstract

We are now more or less confronting a “challenge of responsibility” among both undergraduate and postgraduate medical students and some recent alumni from medical schools in Iran. This ethical problem calls for urgent etiologic and pathologic investigations into the problem itself and the issues involved. This study aimed to develop a thematic conceptual framework to study factors that might affect medical trainees’ (MTs) observance of responsibility during clinical training.

A qualitative descriptive methodology involving fifteen in-depth semi-structured interviews was used to collect the data. Interviews were conducted with both undergraduate and postgraduate MTs as well as clinical experts and experienced nurses. Interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed. The data was analyzed using thematic content analysis.

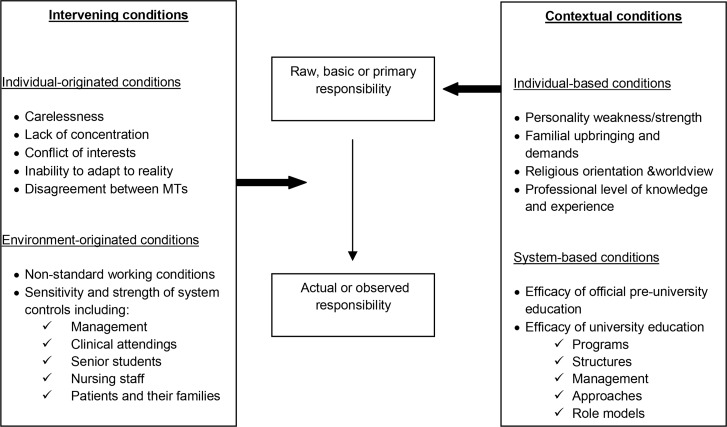

The framework derived from the data included two main themes, namely “contextual conditions” and “intervening conditions”. Within each theme, participants recurrently described “individual” and “non-individual or system” based factors that played a role in medical trainees’ observance of responsibility. Overall, contextual conditions provide MTs with a “primary or basic responsibility” which is then transformed into a “secondary or observed responsibility” under the influence of intervening conditions.

In conclusion three measures were demonstrated to be very important in enhancing Iranian MTs’ observance of responsibility: a) to make and implement stricter and more exact admission policies for medical colleges, b) to improve and revise the education system in its different dimensions such as management, structure, etc. based on regular and systematic evaluations, and c) to establish, apply and sustain higher standards throughout the educational environment.

Keywords: responsibility, qualitative descriptive study, clinical training, undergraduate medical student, medical resident

Introduction

Theoretically, the concept of responsibility represents the readiness – including willingness and ability – to respond to a series of normative requirements (1). In this manner, in practice, responsibility is often explained or even known through the concepts of duty, commitment, obligation, accountability, etc. Generally, health professionals are considered personally accountable for their professional practice (2). The same is true of medical trainees (MTs); they are expected to accomplish their assigned educational duties and to have responsibility for their thoughts, decision-making and behaviors.

The concept of responsibility has now found a special standing in the health care field; it is one of the pillars of medical professionalism (3), affirmed in lots of professional codes of ethics and conduct (4, 5). Nevertheless, despite its wide and general scope of use, the concept itself has received less attention as an independent and ascertainable subject of research. Instead, it has been often approached in the existing literature of the health domain as an intelligible and basic concept with a completely obvious meaning for readers. Given the above exposition, many authors have made a secondary use of the concept, aimed to introduce new aspects or broaden its scopes with respect to a subject of research other than responsibility (6–8).

We are now more or less confronting a “challenge of responsibility” among MTs and some recent alumni from medical schools in Iran. In fact, it seems we are going through a “responsibility crisis” that we have not experienced so sharply before. Careful observations show that this ethical problem includes negative changes in both the degree and quality of responsibility among Iranian MTs. Moreover, as there is a real shortage of related studies in the existing literature, conducting etiologic and pathologic investigations into the problem and the issue(s) involved seems necessary. Therefore, this study aimed to develop a thematic conceptual framework to explore factors initiating the problem among MTs. Additionally, positive and constructive factors were also considered throughout the research. Thus, our main research question was “What elements or factors might negatively or positively affect the concept of responsibility in MTs during their clinical training?” The results can be used for improving the existing medical education and medical ethics curricula and generally enhancing the effectiveness of the present education system.

Methods:

Design

Semi-structured interviews were analyzed undertaking a qualitative descriptive approach. This design was selected as an appropriate modality to explore elements that might affect MTs’ observance of responsibility as an important phenomenon in some Iranian educational settings. In this way, lived experiences of MTs and a number of clinical experts and professional nurses have been analyzed.

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS). We began recruitment by inviting informants –medical trainees – from a convenience sample (9) of individuals known to the researchers. Snowball sampling (9) was used to identify other potential participants. We reasoned that MTs’ educational status (undergraduate vs. postgraduate) and their gender were important criteria that would provide maximum variation. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved. Overall, fifteen interviews were conducted, 6 with undergraduates (3 males) and 5 with postgraduates (3 males). In addition, four more interviews were done with some clinical experts (n=2) and experienced nurses (n=2) to ensure the saturation state within the emergent themes and subthemes. Based on the research purposes, only those undergraduate participants who were in the clinical phase of their trainings (5th to 7th year medical trainees) had the primary inclusion criteria. All postgraduate MTs or residents had the primary inclusion criteria. Moreover, only those nurses who had a high professional experience in SUMS affiliated educational hospitals were interviewed.

Data Collection

A semi-structured, open-ended interview protocol was developed with questions aimed at enabling participants to describe their personal experiences and thoughts about the study subject. Probing questions were also used to deeply investigate conditions, processes, goals and factors that participants identified as significant (10). Overall, probes and reflective statements encouraged participants to provide additional details and clarify their statements. The key question asked MTs to comment on their own observance of responsibility and the elements influencing it, either positively or negatively. Moreover, with the aim of broadening the study scope and enriching the emergent (sub-) categories, a number of additional interviews were held with some clinical experts and professional nurses. They were asked to provide a comprehensive view about MTs’ responsibility in practice. On average, interviews lasted 64 minutes, were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. In order to safeguard ethical considerations, each participant received a set of instructions explaining the purpose of the study, their freedom to participate and a confirmation of confidentiality. Eventually, written informed consents were obtained.

Data Analysis

The transcribed interviews were analyzed using MAXQDA 2007 software (version BI GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The scripts were carefully read several times and coding themes were generated employing a conventional content analysis (11). The codebook was reviewed in regular team meetings and any disagreement was settled by consensus. Using the constant comparison technique (12), additional interviews were held to screen the coding structure and achieve a theoretical saturation (10). This process provided a methodological rigor because of its iterative nature for revising the initial themes and their refinement through subsequent data collection and analysis. Coded data was then grouped and organized using the software.

Results

The saturation state in each group was independent. Yet, the obtained data of both groups were eventually added together and classified into a uniform set of themes and subthemes. Additionally, with the aim of adding external views, the data of the interviews with clinical experts and professional nurses was also scanned and added to this set to ensure saturation state. Here, The final set of data has been presented along two broad themes: i) contextual conditions, and ii) intervening conditions. As can be seen in figure 1, according to the data, each theme contained two sets of individual and non-individual (or system) based factors, which have been illustrated in the contextual and intervening conditions boxes. In the following section, we have tried to present a comprehensive and more detailed view of each theme according to the participants.

Figure 1:

Contextual and intervening conditions extracted as effective in medical Trainees’ responsibility in clinical settings.

Theme 1- Contextual Conditions:

The specific sets of conditions that were the basic groundings of responsibility according to the participants were categorized as contextual. These embedding conditions created a primary or basic responsibility in MTs. Generally, participants believed these basic conditions were either intra-personal or extra-personal. In other words and according to the data, participants thought the two groups of individual and non-individual (or system) based contextual conditions play a role in forming basic responsibility in MTs (figure 1). These conditions are illustrated below with reference to participants’ statements.

Individual-Based Conditions: Generally, most participants believed being responsible is basically an internal characteristic of persons, so it should be discussed based on MTs’ personality. They thought each MT comes to university with his/her unique personality and thus with a unique primary or basic responsibility. In fact, they believed MTs to be of various personal backgrounds and basically differ from each other with respect to their notion of responsibility. For example a female resident made the following comment to explain this difference: “I think much of it [responsibility] must be dependent on the personality [of students]. At least in the beginning each [student] seems really different from the other.“

In this way, some participants believed many instances of lapse of responsibility occurred primarily because of MTs’ personality or character weakness. “Lacking personal commitment to do the assigned duties”, “not having a correct and strong ideology of life”, “lacking moral integrity, compassion, etc. toward others”, “selfishness” and so on were among the negative qualities mostly expressed by the participants. In this regard, a nurse mentioned “a case of selfishness” that she believed to be rather common among undergraduates: “… for instance, some [medical trainees] are used to behave selfishly; in one case, even though I told a trainee about his mistakes, [he] indifferently continued to do the wrong [thing].“

Moreover, some participants believed that the concept of responsibility is largely interrelated with MTs’ “familial upbringing”. In this way, they thought it is important how effectively MTs have been taught to be responsible in the family environment. Of course, attribution of responsibility to families indicates the fact that in Iran, children and almost all adolescents until around 22 to 25 years old are highly dependent on their families especially economically; they usually live with their parents till they get married, and this is more true of girls. In this way, informants thought that the socioeconomic status of families could be used as a good criterion for a rough estimation of the quality of MTs’ primary responsibility. One of the clinical experts described the role of the family in MTs’ responsibility as the following:

“I think that a great proportion of their responsibility has formed during their childhood, as a result of all the actions and interactions they have had in their family environment, especially with their mother and father. I think the same must be true about the surrounding society too.“

MTs’ “religious orientation and world view” was derived as another individual-based factor. All participants were Muslim. Roughly, the data showed that MTs with stronger religious beliefs would act to some extent more responsibly than their counterparts with no or weaker religious beliefs, particularly in hard, pressing and conflicting situations. Among religious beliefs, believing in the afterlife and resurrection seemed to have the strongest power to prevent MTs from committing illegal or unethical doings. Generally, religious trainees often considered themselves accountable to God for their actions and decisions; consequently, they often refrained from taking their duties lightly. The positive effect of having religious beliefs on responsibility was well confirmed by an undergraduate trainee:

“… If I don’t do it [the assigned duty] and as a result a patient is harmed or injured, even if nobody realizes it was my fault, at least I know that I have to be accountable to my God in the afterlife.“

“Little or inadequate professional knowledge and experience” was the last factor stated to be effective in a few cases of lapse of responsibility. An example of this issue was illustrated by a resident of radiology; she explained how lack of professional knowledge and experience in junior students could cause lapses to occur:

“Some days a junior [undergraduate] student is sent to the MRI department for a not simple, specialized consultation. Unfortunately, these students often know very little about even simple MRI or CT images. It is even worse when they know the disease they have been sent to the MRI department for.… We often see they transfer the wrong information to their wards; this is problematic for the patients and of course ourselves.“

System-Based Conditions: Our Findings show that non-individual or system-based conditions were the second kind of contextual conditions that played a fundamental role in MTs’ observance of responsibility. Participants attributed this role to both official pre-university and university education. They believed pre-university official education is very important in the healthy development of a sense of responsibility in trainees. They stated that they thought trainees should be taught, trained and acknowledged in practice with respect to the concept of responsibility through secondary and higher schools. Yet, some informants believed the present pre-university education system does not meet this essential requirement so well and thus responsibility related problems usually continue to exist in the higher education period. One of the nurses expressed her opinion about this issue and said:

“I really believe that the role of pre-university education in MTs’ responsibility is crucial and critical; I know it in my heart. Of course, I think this system must be the first to be reformed fundamentally. Moreover, the present system [of medical education] also seems weak and feeble in training students to be as responsible as a doctor should really be.“

Additionally, the “efficacy of the medical education system” with respect to its various dimensions of “structure”, “programming”, “management” and “approach” was regarded by almost all participants as a highly effective context in MTs’ responsibility. Overall, they thought a large proportion of responsibility related problems basically resulted from system defects. Given the above explanation, instances of the participants’ statements regarding the aforementioned dimensions have been illustrated in table 1.

Table 1:

Examples of participants’ statements with respect to different dimensions of “medical education system” with negative effect(s) on MTs’ responsibility.

| Dimensions of medical education system | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Structure | Programming | Management | Approach |

| “As duties are not always well-defined, disagreement is common; as a result, some tasks might be done with delay.”(UG) | “We receive no briefing when we start a new ward. We are programmed to learn many things by trial and error!” (UG) | “When some guys go on leave just to study a while before an exam, they just put us under pressure. There is no effective control on the furloughs!” (PG) | “I think there is a problem with the system. We realize the focus is on individuals and personal development, not team work.” (N) |

| “Practically, 6th and 7th year MTs work almost equally in practice, and that partly has harmed the process of senior obedience.” (A) | “The on call resident was not from that ward, so when I called her in for an emergency case, she did not know the patient at all.” (UG) | “Our senior [Intern] seemed free to compel us [juniors] to do bonded labor when we disagreed with his unreasonable demands.” (UG) | “Relationships and interactions seem completely physician-oriented. We prefer to ignore much of trainees’ misconducts.” (N) |

| “If I fail a multiple-choice test just because of one or two questions, I have lost one year of my life.” (PG) | “We were notified just after we did something wrong; sometimes we were not taught punctually enough.” (UG) | “I noticed that the management was indifferent to my constructive criticism, so I preferred to be silent from then on.” (PG) | “The values have become instrumental. Mostly, the focus is on exam scores, not for example on trainees’ commitment to patients or such.” (A) |

| “Graduation is not based on objective and real criteria; trainees need to be assessed professionally….” (A) | “In reality, commitment, responsibility and so on has no place in trainees’ evaluation forms.” (N) | “Attendings are reluctant to involve the ward nurses in evaluation of medical trainees’ professional conduct.” (N) | “The focus is now on bureaucracy; trainees are weak in building an effective therapeutic relationship with patients.” (N) |

| “In the presence of fellows, residents and undergraduates may be bypassed by the attendings.” (A) | “Daily, a large proportion of educational hours is wasted before starting morning rounds. Students spare time with no definite task to do.” (N) | “I became thoroughly bored and hopeless when they [attendings] unjustly carped at me about my low score from time to time.” (PG) | “We sometimes do therapeutic care, while I think the definite purpose should be educational.” (UG) |

UG: undergraduate student; PG: postgraduate student; N:nurse; A: Clinical Attending Physician

Moreover, some informants alluded to “role models’ fundamental part” in the development of responsibility in MTs. They stated that presence of positive role models could practically have considerable positive impacts on the professional behaviors of MTs. Surprisingly; MTs often gained positive and constructive perceptions even from negative role models. For example, a 7th year undergraduate trainee shared a distressing experience about how irresponsibly an attending physician had given an old man the news of his cancer diagnosis:

“On a routine day we were standing near the patient’s bed and listening to the new clinical findings. Meanwhile, the worried old man repeatedly asked, ‘What’s wrong with me? ’Unfortunately, after about four times, the attending physician got angry and told him loudly, ‘You have cancer and you won’t get well at all!’After that the patient became completely quiet and in the following night he went into cardiac arrest. From that time on, I have behaved very conservatively about breaking bad news to patients.“

Theme 2- Intervening Conditions:

We considered conditions as intervening when they altered MTs’ “primary responsibility” and transformed it into the “actual or observed responsibility”. On the other hand, by utilizing intervening conditions, we could explain why MTs might perform the same responsibilities differently or how a primary responsibility can transform or develop into a secondary one in reality (figure 1). It is noteworthy that according to the data, these alterations often involve negative and deteriorating changes and forms. As can be seen in figure 1, like the previous theme we categorized intervening conditions into two sets of “individual-related or individual-originated” and “non-individual or environment-related (or originated)” conditions. Conditions were considered as individual-originated if MTs themselves had a main role in their creation, and they would be considered as environment-originated if extra-personal or system factors had a primary role in their creation. Below, these two conditions are explained according to the participants:

Individual-Originated Intervening Conditions: “Carelessness” was introduced as one of the main causes of unintentional irresponsibility. “Taking the clinical practice (too) easy” and “forgetfulness” were two important underlying causes of carelessness based on the data. As an example of the former, we cite a short explanation by a senior student about one of his experiences when he was on call:

“It was around 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning. The nurse in charge explained to me a patient’s medical condition on the phone. Given the explanations, I thought it was the normal course of her [the patient’s] disease. That was a very unfortunate mistake, because during morning round I was embarrassed to find out that I had lost the patient.”

In the case of forgetfulness, MTs believed “non-standard and heavy workload” and thus the resulting “work exhaustion” was the most significant factor involved. Furthermore, “lack of concentration” was expressed as the main result of work exhaustion. Moreover, life hassles, whether familial, social or economic, were the most significant elements that could cause poor concentration especially among postgraduates. Some of these stressors are well exemplified in the words of a fourth year resident:

“Sometimes you may have problems with your wife or you may not have enough money to rent a small place to live or even one of your family members falls sick; certainly, these situations could make you feel exhausted and consequently distract you from your practice.”

“Conflict of interests” was pointed out as another intervening condition that may occur when MTs put their interests and conveniences over anything else such as their educational duties or even patients. Overall, the most dominant instances of conflict occurred when MTs were involved in studying for an imminent and important examination. Final exam of clinical wards, promotion exams or even a residency one were as such according to the participants. This fact was demonstrated well in the interview with a first-year resident; she explained how she was studying for residency exam during her internship: “… Ok, especially around the exam I tried to do my visits faster than ever to save more time for studying; I tried to limit my attendance at the ward; whenever I found time I went to the hospital studying room.“

“Inability to adapt to the realities” of medical care environment or medicine itself were the other intervening factors that could weaken MTs’ motivation and thus dampen their enthusiasm in practice. Participants believed medicine and its demanding conditions either during education or after graduation can be beyond the limits of some MTs’ endurance, and could thus get them exhausted and cause them to lose their “primary motivations” for studying or practicing medicine. “Early and premature exposure to difficulties of working physicians”, “looking for easy achievement of fame and wealth in medicine”, and “perceiving medical practice and its requirements as overwhelming” were amongst the most prevalent elements affecting MTs’ primary motivations negatively. For example, a 6thyear undergraduate student expressed some of these facts and said, “I think some [students] see that they cannot reach what they expected and planned for easily; they cannot have those things [money and fame] soon and with ease and are very likely to become disinterested and bored gradually.“

Finally, destructive “disagreements between MTs” was expressed to be worth considering as one of the underlying causes of delays in meeting patients’ medical needs. This issue was well illustrated in a real story narrated by a medical resident:

“… I think our senior resident intended to retaliate something by neglecting the request of the senior resident of the internal department; I remember that the patient involved was detained for an additional day till the disagreement was eventually settled.“

Environment-Originated Intervening Conditions: Based on the data, these conditions originate mostly from the education system itself and could influence MTs’ responsibility either negatively or positively. “Non-standard working conditions” was one of the main elements expressed by many participants to have unintentional negative effects on MTs’ observance of responsibility. “Heavy workload”, “overcrowded emergency rooms” and “inadequate number of professionals” (whether undergraduate or postgraduate MTs or general physicians, nurses, etc.) were common instances of this sub theme as pointed out in lots of interviews. Neglecting patients and their medical needs was the most significant consequence of these substandard conditions as affirmed by one of the participant residents:

“These [conditions] occurred especially during first and second years of our residency. Duties were really heavy especially when we were in charge of emergencies, when patient load was really high. You see, an additional problem was our every other day 24-hour on call duties! All that put us under a pressing stress; … it naturally might have caused some things to be overlooked.“

As another intervening condition, many participants stated that MTs’ observance of responsibility was directly related to the sensitivity and strength of system controls. As shown in table 2, participants believed that “system control “should be seriously exerted through its different dimensions if it is going to be effective and influential in practice. These dimensions could be considered as different levels of managerial control within the education system. Instances of participants’ statements regarding these levels of control have been illustrated in table 2. As participants pointed out, most examples are about the control flaws in the current system of medical education.

Table 2:

Examples of participants’ statements with respect to different dimensions of the current system controls

| Dimensions of system control | Examples of participants’ statements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital or department management | “If there was powerful supervision, the nurse could not lie so easy and escape from justice.” (UG) | “We might feel the system is not supportive and easily ignore our hard condition; unjust, one-sided demands are a lot.” (PG) | “The way I see it, encouraging and punitive policies are absent, not enough or are implemented ineffectively.”(N) |

| “Usually no incident sheet is filled; preventable events are not followed and problems are usually repeating.”(N) | “Issues are not usually handled preventively unless [they] transform into challenging and serious problems.” (N) | ||

| Clinical attending | “When the attending was tough and strict, we did tasks carefully and attentively.”(UG) | “If the attending supervision was enough, the student could not have misused his position and done such an unconscionable act.”(A) | “The boy [student] neglected my prompt order; after I told him about the consequences, I warned him that I would report future instances and thus he would fail.”(A) |

| Senior students | “Clinical trainings were largely the seniors’ responsibility, whether or not they wanted to teach us.”(UG) | “Residents easily masked errors; for they knew they were the first [one] who would be accountable to the attending about the ward incidents.”(UG) | “I usually assigned to juniors some duties; then, I would supervise their performance.” (PG) |

| Nursing staff | “We-head nurses-have no formal role in the control of the ward disciplines to be observed by medical trainees.” (N) | “Sometimes, we act as the go-between; we inform MTs about patients’ concerns and dissatisfactions.” (N) | “I cannot ignore some MTs’ misconducts and I do report to those in charge as a duty.” (N) |

| Patients and/or their families | “Of course, some family members’ sensitivity about their patients might compel us to act more carefully in practice.” (PG) | “We notice MTs are more careful about patients that not only know their rights but demand them to be observed.” (N) | “When the patient is quite knowledgeable medically and asks precise questions, trainees usually became more careful in their doings.” (A) |

UG: undergraduate student; PG: postgraduate student; N:nurse; A: Clinical Attending Physician

Discussion

Our findings highlight important factors affecting MTs’ responsibility in educational settings of clinical care. Participants were representatives of both groups of undergraduate and postgraduate MTs. Moreover, interviews with clinical experts and professional nurses were conducted to broaden and deepen the scope of the study by adding external or non-trainee views to it. As explained, two sets of contextual and intervening conditions actively played a role in MTs’ observance of responsibility. According to the data and as shown in figure 1, considering contextual conditions as a unit we might allocate each MT a “raw, basic or primary responsibility”. A potential consequence of this statement –or claim–would be that every MT would have a primary and distinct responsibility measure that can be determined or assessed by a well designed quantitative instrument like a questionnaire. Of course, as explained in the second theme, primary responsibility often changes in interaction with a number of intervening conditions to yield a secondary, actual or observed responsibility. In fact, what we see in reality as each MT’s responsibility is the output resulting from a complex and multidimensional interaction of intervening conditions with contextual conditions.

As figure 1 indicates, two groups of individual and system-based conditions form contextual conditions. We think the best way to effectively control some individual-based conditions, especially those that are apparently incompatible with the spirit of medicine itself, is establishing and implementing stricter and more realistic university admission policies. In this way, development of powerful and reliable instruments seems to be necessary, which in turn calls for conducting more comprehensive and fundamental researches (13–15) to set more confident predictors for effectively screening medical school applicants.

Moreover, in the case of pre-university education system, revising and if needed reforming the current educational curricula towards more efficient responsibility oriented ones is suggested as a long-term fundamental program. Generally, as Kyoshaba (16) has discussed in her dissertation, many scholars agree that the education system can hypothetically influence students’ academic performance; we think if students are trained to be more responsible at schools, certainly much less time and energy would be spent at colleges and universities on training responsible professionals.

Pragmatically, we think this concept should be formally approached in both pre-university and higher education systems through establishing coherent policies. In this way, it is also necessary that the concept of responsibility be implemented through well-structured and practical curricula, to be incorporated in tests and closely monitored in everyday educational activities and to be taught and encouraged through positive role models (17, 18).

Nevertheless, this study revealed that MTs’ “religious beliefs” might have a constructive role in their observance of responsibility, but more thorough investigations will be necessary. Although for many years there has been serious skepticism about any positive effects of students’ personal religiosity on their academic performance, there is growing evidence that this relationship may exist and it has been scientifically proven in some recent studies (19, 20). Given that Iran is a highly religious country with dominance of Islam, bolstering religious knowledge and understanding of MTs might be very helpful, especially in improving the quality of their professional responsibility.

As mentioned above, in the case of low “professional knowledge and experience” of some junior MTs and the related negative consequences, we suggest the issue ought to be handled through more effective “senior supervisions”. We believe this is an easily preventable issue that just needs more attention from seniors. Thus, other than the attending physician, senior trainees should be trained at least in the general features of an effective and competent supervision and management. In order to reach this purpose, it is necessary to carry out regular comprehensive evaluations and then provide seniors with objective feedbacks on their strengths and weaknesses. Moreover, establishing advisory services in the hospitals and holding a number of related informative and developmental programs regularly seem helpful.

Implementation of appropriate educational programs, structures, management and approach seem to be essential to the education system and are highly influential in MTs’ observance of responsibility; therefore, undertaking regular evaluations concerning these dimensions is also proposed for assessing the present status, determining defects and making developmental plans.

Generally, there are practical and helpful guidelines designed for MTs to help them cope with stress and burnout as two significant individual intervening conditions (21). The problem of “work exhaustion” and its subsequent complications like “carelessness”, “lack of concentration”, etc, can be successfully addressed by improving the current education system and as needed, and establishing new standards throughout the system (22, 23).

Presently, it seems there are some critical and of course preliminary points in our education system that need to be reviewed and revised based on the appropriate global standards; “student workload”, “trainee-to-patient ratio”, and “content and way of conducting examinations” to name but a few. This standardization would enhance the quality of MTs’ responsibility according to the data.

Standardization also seems really influential in decreasing frequency and intensity of cases of conflict of interest among MTs. It seems that lots of these cases could be efficiently handled by implementing more effective supervisions, but clearly, some difficult circumstances in the present system might have the potential to provoke conflict. For instance heavy workload might not provide enough time and energy for MTs to get minimum score in some examinations. Certainly, these problems require comprehensive, practical and immediate solutions; otherwise, patients in particular would suffer.

According to the published literature (24, 25) and as expressed by a great number of participants, “motivation” has a highly significant role in MTs’ academic performance. Moreover, as stated in the data, some informants believed MTs’ high primary motivations gradually decrease, causing mentally and/or emotionally exhausted feeling and burnout; consequently, this problem would lead to responsibility abdication. We recommend taking intrinsic motivations into consideration when admitting medical school applicants and also fostering motivation (26, 27) in the educational environment. We also propose identifying, then fully comprehending and dealing with factors that are working as negative extrinsic factors in the current education system, such as those explained during non-individual contextual or intervening conditions (figure 1); this action might alleviate the problem of “decreased motivation” among MTs.

A close collaboration of senior trainees, clinical attending physicians and head nurses in each clinical ward is proposed for the timely reporting of cases of “disagreement between MTs” and their professional solutions. Additionally, developing practical guidelines might be very helpful in handling related issues preventively (28). In this regard, we also suggest that the history of challenging cases be used – for instance by hospital or clinical department leaders –as a valuable source to prevent and manage similar forthcoming incidents.

Finally, as shown in table 2, the data demonstrated that there are serious problems with respect to different dimensions of the existing “system control”. In this way, the meticulous attention of those in charge of hospitals, departments and wards is needed to investigate the issue more closely, take it more seriously and make prompt attempts to prevent shortcomings caused by further continuation. Also, in order to achieve this purpose, we suggest holding regular and developmental programs and informative seminars or group sessions for senior trainees, clinical attending physicians, department managers or any other involved professional groups in the role of a controller or manager. Moreover, it is proposed that regular and precise qualitative and quantitative evaluations be carried out with the aim of assessing the efficacy of the present controls and controllers and providing those in charge with constructive feedback.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that responsibility in MTs practically forms from interactions between contextual and intervening conditions. Moreover, as there is a real dearth of research on the subject of responsibility, this study contributes to related literature and might provide a helpful grounding for understanding the concept of responsibility in MTs. Conclusively and according to the study data, the following three measures seem essential for improving observance of responsibility in MTs: a) to make and implement stricter admission policies for medical colleges, b) to constantly improve and revise the education system in its different dimensions such as management, structure, etc. Based on regular and systematic evaluations, and c) to establish, apply and sustain higher standards throughout the educational environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating medical students and residents, clinical experts and nurses for their kind cooperation in the collection of data. Moreover, we would like to thank Dr. Sedigheh Ebrahimi for her kind assistance in the professional editing of the article.

This study comprises part of a more extensive research, a PhD dissertation in medical ethics, which has been registered under number 5965 and financially supported by the Vice-Chancellery of Research and Technology of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Williams G. Responsibility as a virtue. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2008;11(4):455–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch J. Clinical Responsibility. United Kingdom: Radcliffe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thistlethwaite J, Spencer J. Professionalism in Medicine. New York: Radcliffe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal Medicine. ACP-ASIM Foundation. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. European Federation of Internal Medicine Medical professionalism in the new millennium: aphysician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous NEOMED Expectations of student conduct and professional commitment, 2012–13. http://www.neomed.edu/students/studentaffairs/Student%20Handbook%20and%20Policies/student-honor-code/expectations-of-student-conduct-and-professional-commitment-2012-13.pdf (accessed in 2013).

- 6.Kwizera EN, Iputo JE. Addressing social responsibility in medical education: The African way. Med Teach. 2011;33(8):649–53. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.590247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs T, McLean M. Creating equal opportunities: the social accountability of medical education. Med Teach. 2011;33(8):620–5. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.558537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boelen C, Woollard B. Social accountability and accreditation: a new frontier for educational institutions. Med Educ. 2009;43(9):887–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuzel A. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: APractical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charmaz K. Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. USA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Julian ER. Validity of the medical college admission test for predicting medical school performance. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):910–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haight SJ, Chibnall JT, Schindler DL, Slavin SJ. Associations of medical student personality and health/wellness characteristics with their medical school performance across the curriculum. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):476–85. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318248e9d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiser S, Santelices MV. Validity of high-school grades in predicting student success beyond the freshman year: high-school record vs. standardized tests as indicators of four-year college outcomes. http://cshe.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/shared/publications/docs/ROPS.GEISER._SAT_6.13.07.pdf (accessed in 2013).

- 16.Kyoshaba M. Factors affecting academic performance of undergraduate students at Uganda Christian university. http://news.mak.ac.ug/documents/Makfiles/theses/Kyoshaba%20Martha.pdf (accessed in 2013).

- 17.Byszewski A, Hendelman W, McGuinty C, Moineau G. Wanted: role models - medical students’ perceptions of professionalism. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:115. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curry SE, Cortland CI, Graham MJ. Role-modeling in the operating room: medical student observations of exemplary behavior. Med Educ. 2011;45(9):946–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Line CR. The relationship between personal religiosity and academic performance among LDS college students at Brigham Young University. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI3185795/ (accessed in 2013).

- 20.Jeynes WH. The effects of religious commitment on the academic achievement of urban and other children. Educ Urban Soc. 2003;36(1):44–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurd CL, Monaghan O, Patel MR, Phuoc V, Sapp JH. Medical student stress and burnout. www.texmed.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=26900 (accessed in 2014)

- 22.Anonymous Student Workload Policy. http://www.victoria.ac.nz/documents/policy/student-policy/student-workload-policy.pdf (accessed in 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anonymous Standards for call duty and student workload in the Clerkship. Undergraduate Medical Education Executive Committee. 2013. http://wbacademy.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/Standards-for-call-duty-and-student-workload-in-clerkship_revised-2013-01-15.pdf (accessed in2013).

- 24.Kusurkar RA, Ten Cate TJ, Vos CMP, Croiset G. How motivation affects academic performance: a structural equation modelling analysis. Adv Health SciEducTheory Pract. 2013;18(1):57–69. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9354-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusurkar RA, Ten Cate TJ, Van Asperen M, Croiset G. Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: a review of the literature. Medical Teach. 2011;33(5):e242–e62. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.558539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brissette A, Howes D. Motivation in medical education: a systematic review. Webmed Central MedEduc. 2010;1(12):WMC001261. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glasson J, NC D, Plows CW, Clarke OW, et al. Disputes between medical supervisors and trainees. JAMA. 1994;272(23):1861–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]